Abstract

In his 1967 Fundamentals of Musical Composition, Arnold Schonberg described the sentence as a basic tool for organizing themes. Over the past thirty years, a growing number of scholars have been reexamining Schoenberg's concept of the sentence and revealing it to be an important compositional device for a wide variety of composers. However, with rare exception, each of these studies has focused on specific composers or style periods and therefore employs conventions appropriate to their subject. As a result, many definitions of the sentence in use today are either too broad to be meaningful or too specific to a certain genre, limiting the analyst’s ability to make connections between styles. Despite the apparent ubiquity of the sentence as a compositional practice, a broad examination of how the sentence functions across different styles and historical periods is missing from the literature. The authors of this article examine the importance of the sentence throughout the history of tonal music, and at the same time present a taxonomy of sentence structures to aid in making comparisons. Drawing on more than 200 examples from Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and popular music styles, the authors offer an approach that honors Schoenberg’s original concept of the sentence while updating the terminology for broad application, thereby streamlining the connections between past and current research on the sentence in its various guises. This authors propose five types of sentence structures: simple sentences, sentences with delayed fragmentation or no fragmentation, expanded sentences, truncated sentences, and imitative sentences.

Over the past thirty years, a growing number of scholars have been reexamining Schoenberg's concept of the sentence.1 A survey of these studies reveals the sentence to be an important compositional device for a wide variety of composers.2 However, with rare exception, each of these studies focuses on specific composers or style periods and therefore employs conventions appropriate to their subject. As a result, many definitions of the sentence in use today are either too broad to be meaningful or too specific to a certain genre, limiting the analyst’s ability to make connections between styles. Despite the apparent ubiquity of the sentence as a compositional practice, a broad examination of how the sentence functions across different styles and historical periods is missing from the literature. The authors of this article examine the importance of the sentence throughout the history of tonal music, and at the same time present a taxonomy of sentence structures to aid in making comparisons. The authors offer an approach that honors Schoenberg’s original concept of the sentence, as well as his 37 chosen examples, while updating the terminology for broad application, thereby streamlining the connections between past and current research on the sentence in its various guises.

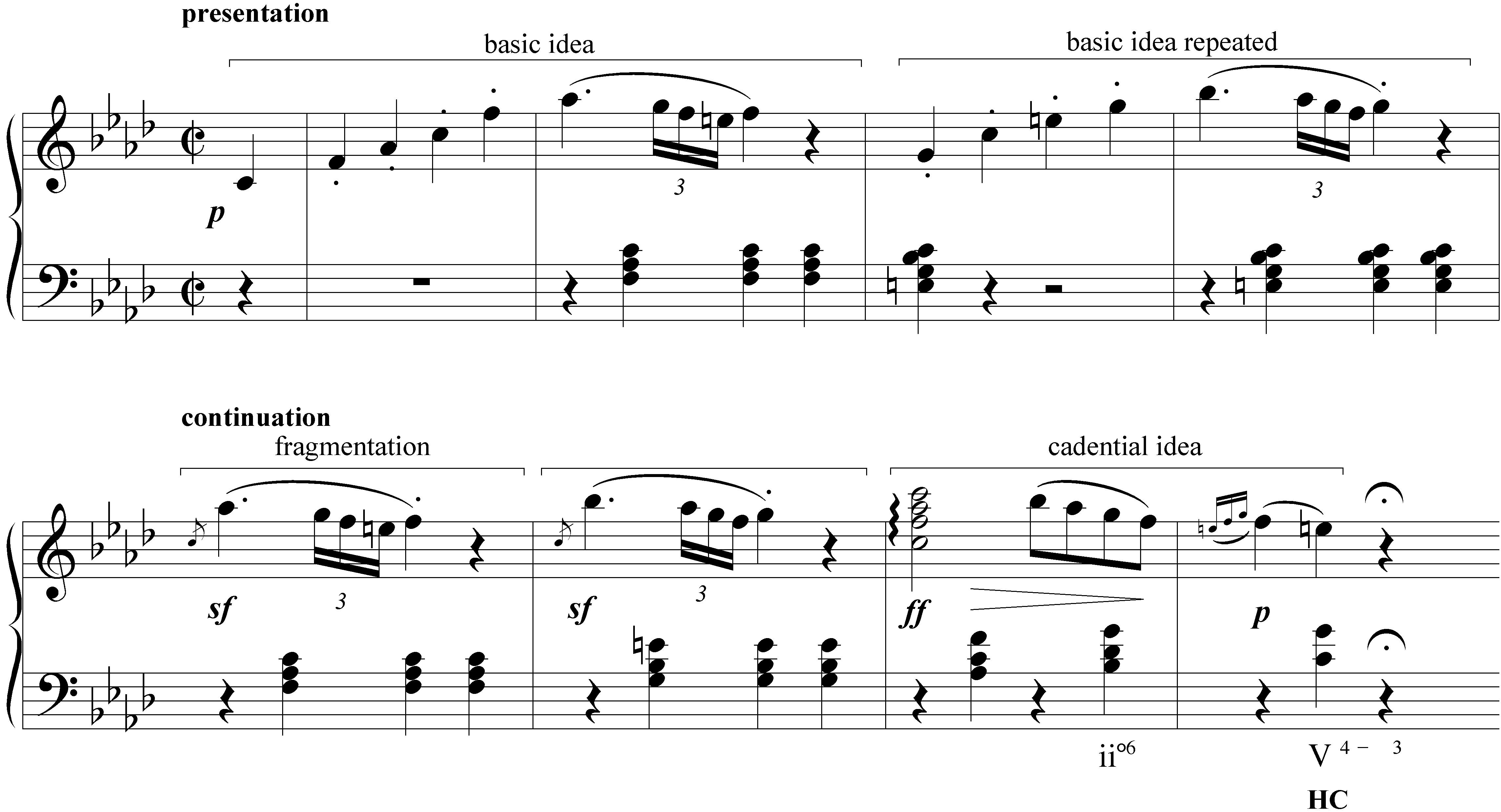

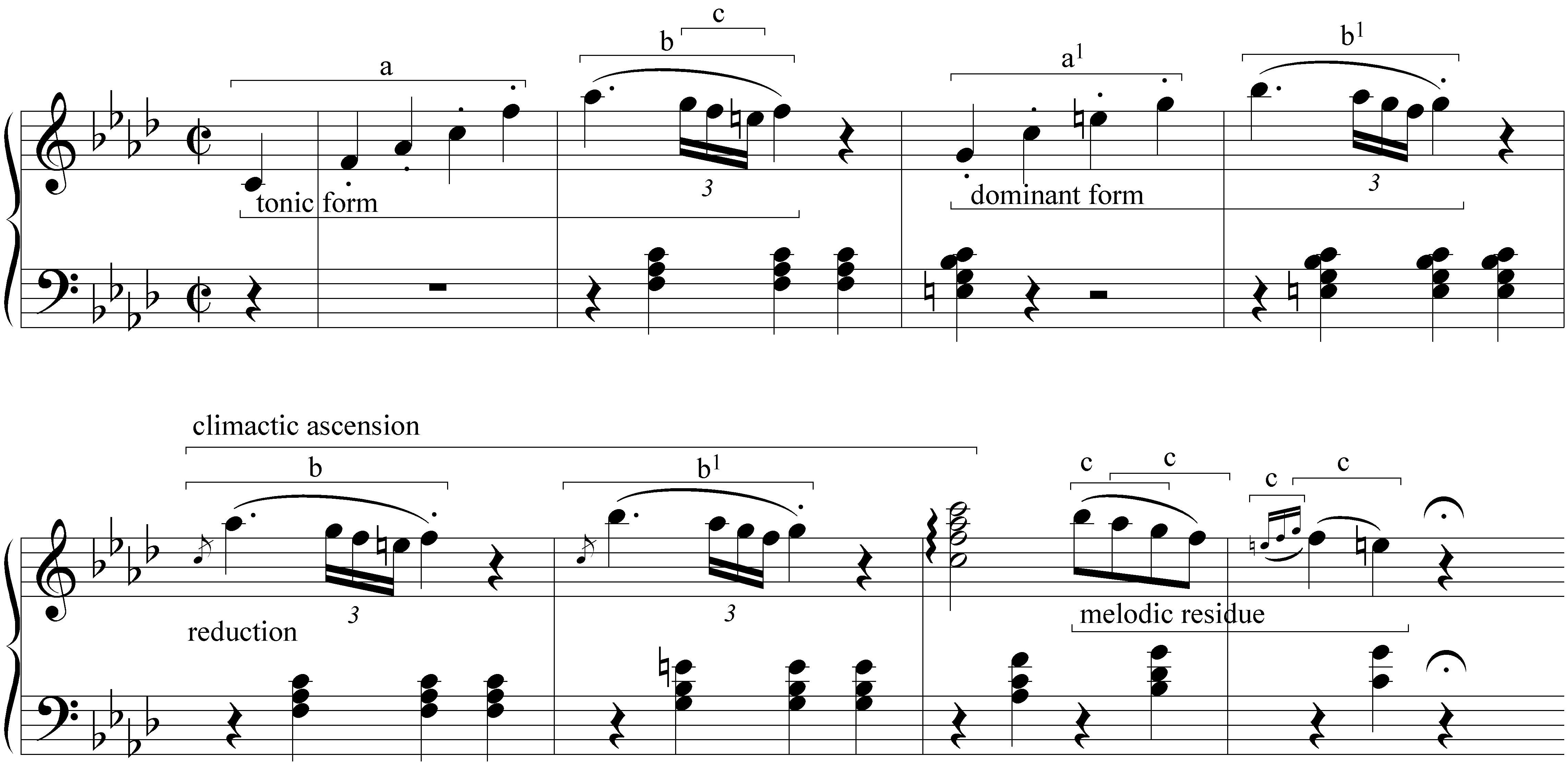

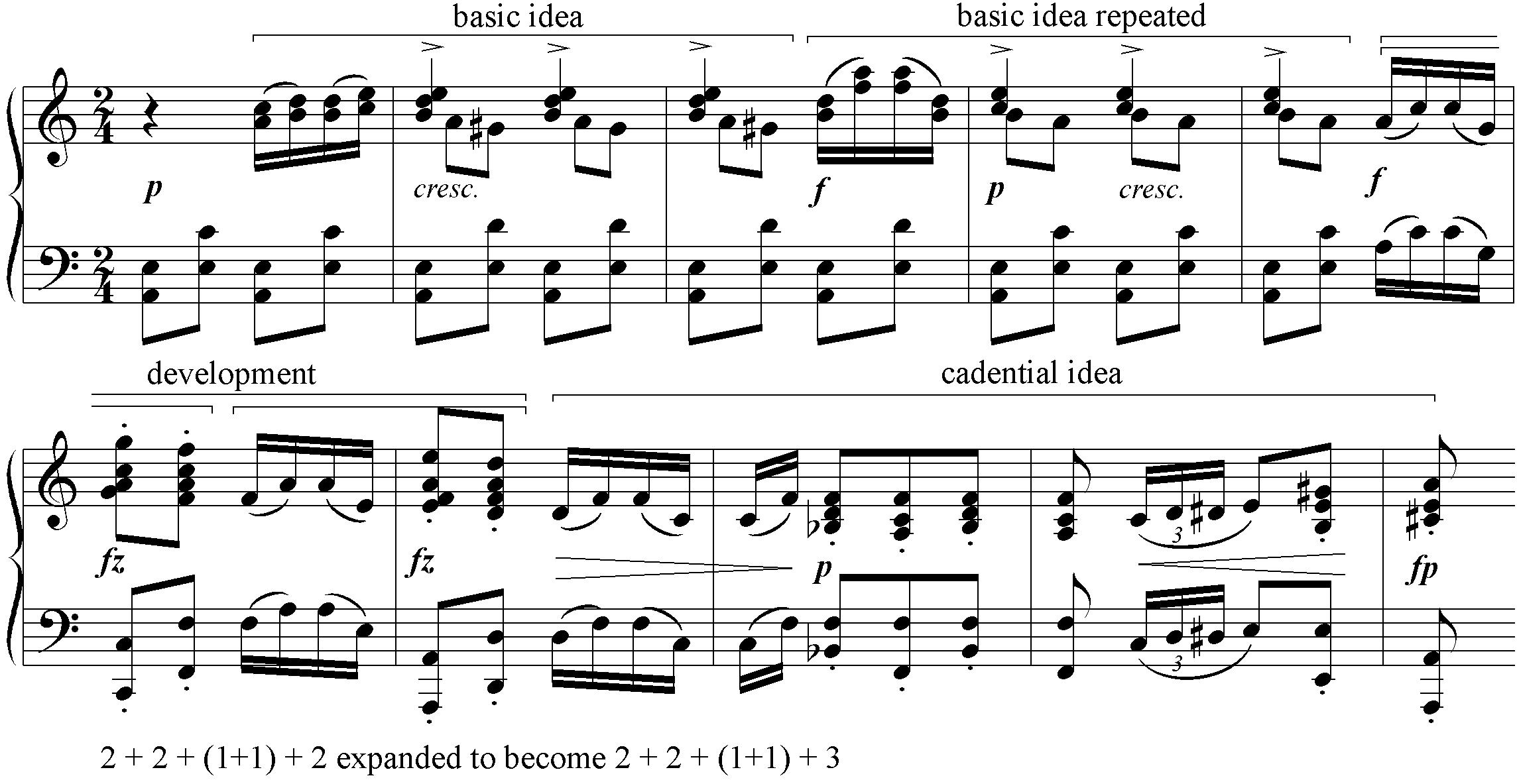

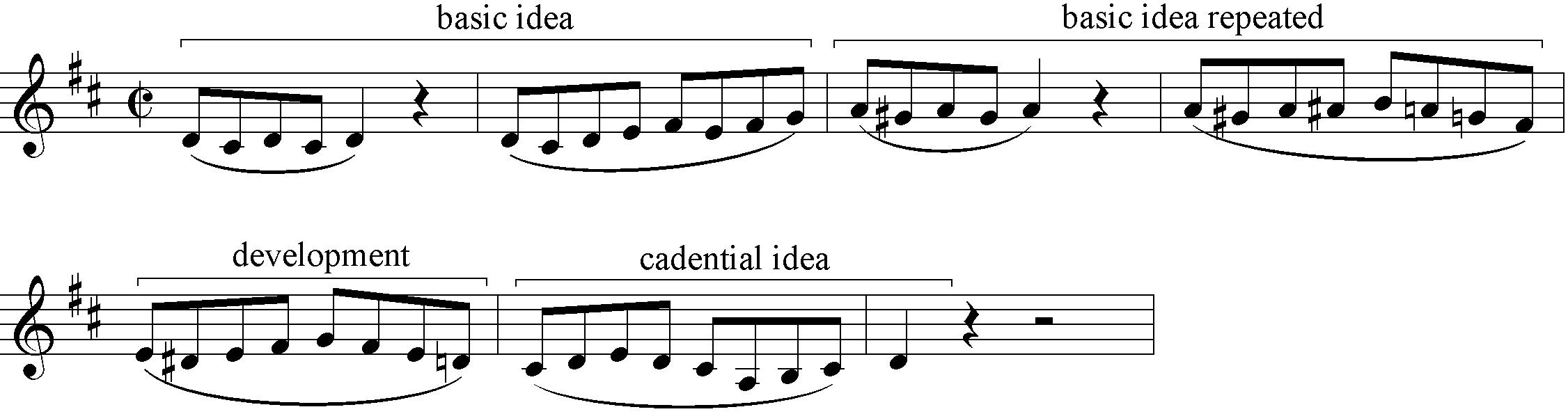

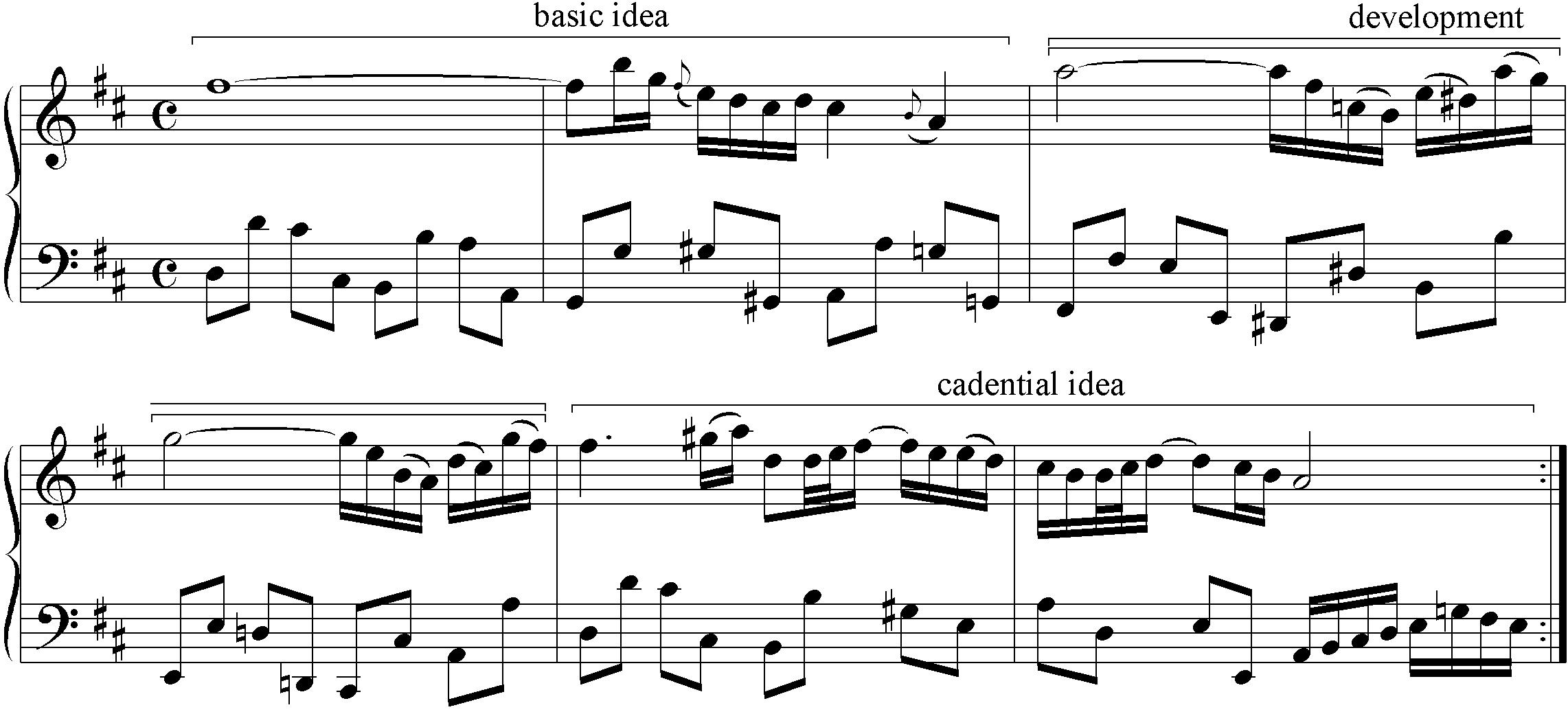

To Schoenberg both the proportions and the internal functional relationships were important to the definition of the sentence, though he stated that a rigid adherence to the proportions he gave was not necessary for the concept to be employed.3 Schoenberg's first example of the sentence, measures 1-8 of Beethoven's Piano Sonata Op. 2, No. 1, captured both its characteristic proportions and its internal functional relationships. Figure 1 shows two analyses of this passage. Figure 1a labels the sentence structure according to Caplin's terminology,4 while Figure 1b gives Schoenberg's own analysis that labels motive forms and demonstrates how mm. 5-8 are a gradual liquidation of the material from the basic idea.5 Figure 1a highlights how the two-bar basic idea, immediately repeated with variation, forms the presentation. This presentation is followed by a continuation that begins with the development of a motive from the basic idea. The development divides neatly into two halves, each half presenting a fragment of the basic idea. Finally, the continuation is concluded by a clear two-bar cadential idea, rounding out the overall eight-bar design. In the Schoenbergian sentence, it is the relative proportions of the model that matter, not the notated length of the segments. Thus, an example with the proportions doubled or halved should be considered equivalent to the segmentation given in Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 2/1, I, mm. 1-8, locus classicus for the sentence, showing Caplin’s analytical labels

Figure 1b. Schoenberg's analysis of Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 2/1, I, mm. 1-8

However, an analysis of Schoenberg’s thirty-seven examples reveals that he did allow for some flexibility in the degree to which a passage must match his practice form to be considered a sentence. Six of his examples featured a basic idea that is not repeated; eight examples featured a continuation that begins with a segment that is not half as long as the basic idea; and fewer than half of his examples were expressions of the 1:1:2 proportions (basic idea : basic idea : continuation), a ratio that received much attention in the literature. Schoenberg wrote, “a practice form is only an abstraction from art forms, sentences from masterworks often differ considerably from the scheme. Among the illustrations the most obvious deviation lies in the number of measures.”6 While the proportions may be flexible, the internal functions are not. In each of Schoenberg’s examples, the continuation began with material that is motivically related to the basic idea, and in over half of his examples, Schoenberg labeled motive forms as he did in his analysis of the opening to Beethoven's Op. 2, No. 1.

In order to codify the flexibility in Schoenberg’s examples for broader application, we propose five types of sentence structures: simple sentences, sentences with delayed fragmentation or no fragmentation, expanded sentences, truncated sentences, and imitative sentences.7 It is important to note that many theorists have generalized the sentence to simply a a b without specifying any proportions at all (in which case it could easily be confused with bar form) or as simply (2 x 2) + 4.8 We maintain that the definition cannot be generalized that much without the concept of the sentence losing its character. All five sentence types presented here have the same characteristic sequence of formal functions (expository-developmental-cadential)9 and have proportions that are directly relatable to the practice form as described in Figure 1 (though we will follow Schoenberg in recognizing both truncations and expansions of the proportions, as the names of our third and fourth types suggest).

The Five Types of Sentences

Simple Sentences

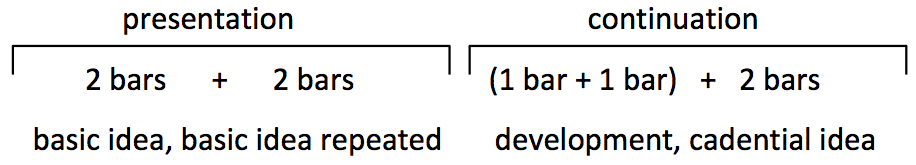

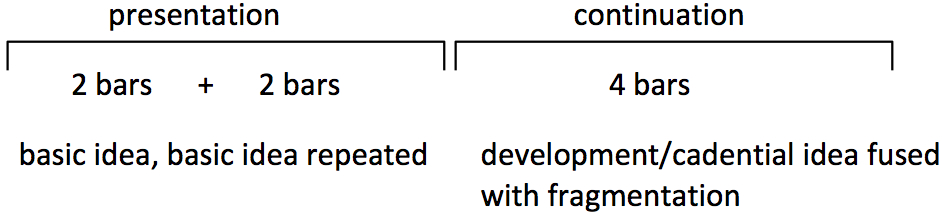

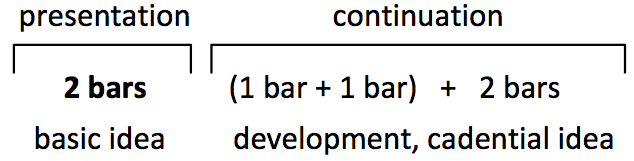

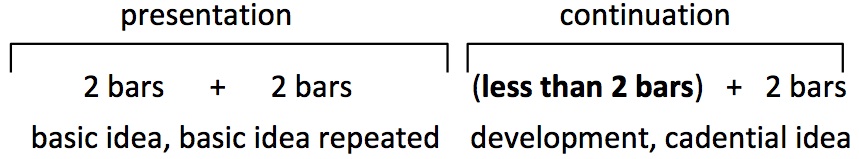

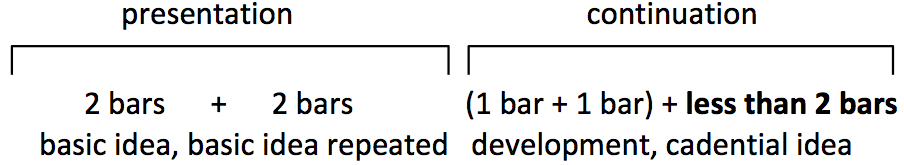

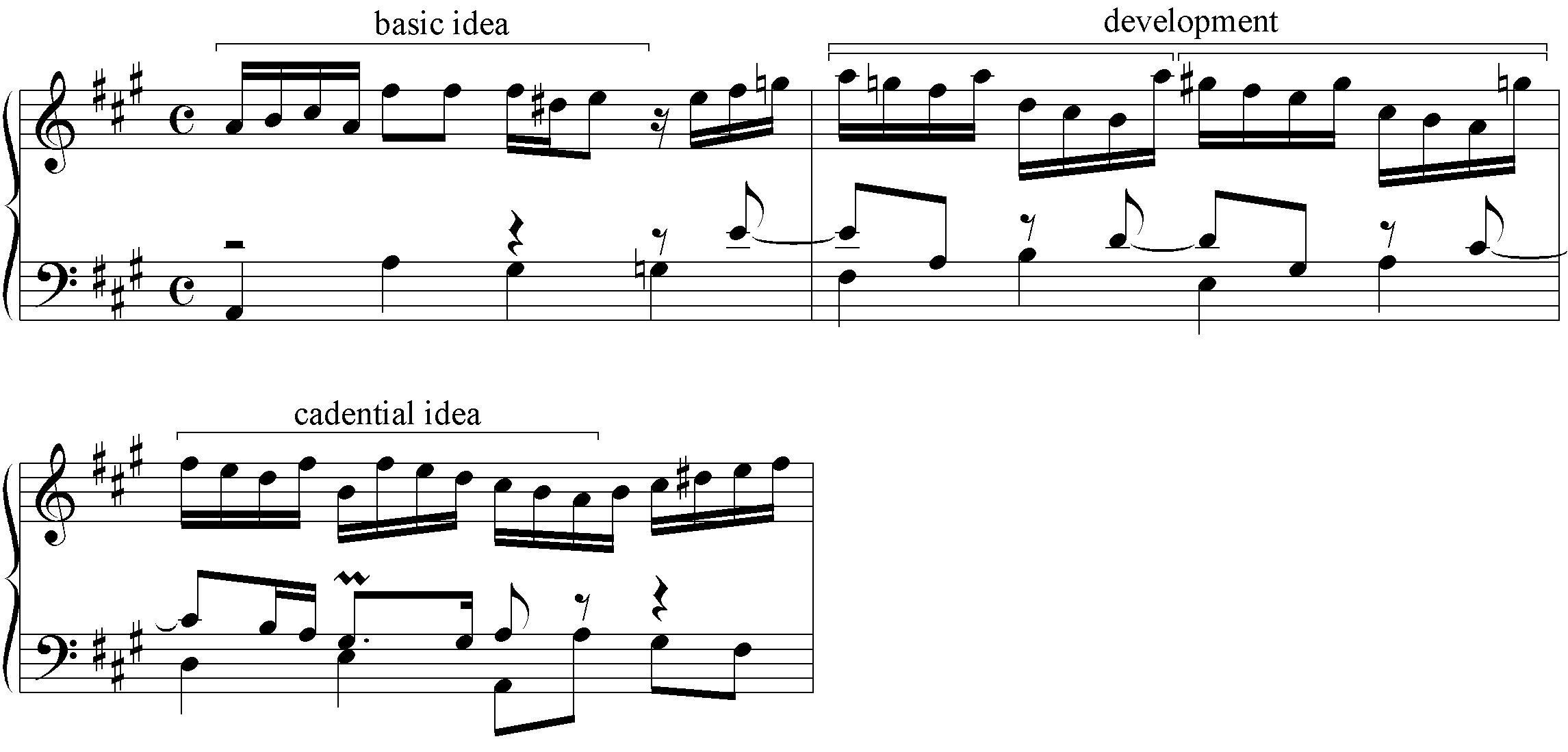

Simple sentences, modeled in Figure 2, adhere most closely to the form as it is realized in Figure 1. Simple sentences maintain a 1 : 1 proportional relationship between the presentation and continuation, as well as between the two iterations of the basic idea. However, the internal proportions of the continuation may be in one of two commonly found relationships. Figure 2a shows a continuation that begins with two bars of development and ends with a two-bar cadential idea. Figure 2b outlines a common variation, where the continuation begins with three bars of development and ends with a one-bar cadential idea. Again, the relative proportions define the simple-sentence type rather than the actual number of measures. Therefore a sentence with the proportions doubled or halved would still be labeled a sentence. According to the taxonomy proposed here, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op.2/1 (Figure 1) is a simple sentence. Figures 3a-c provide simple sentences from the Baroque and Romantic eras.

Figure 2a. Simple sentence model with 2-bar development

Figure 2b. Simple sentence model with 3-bar development

Since a characteristic sequence of functions–expository, developmental, cadential–defines the sentence, and developmental techniques can often be difficult to trace, this article will spell out how the basic idea is developed in each example. In Example 3a, the basic idea is developed in the continuation by compressing the Eb-Ab descent of a perfect 5th from downbeat to downbeat into the first two beats of measures 5 and 6 (D-G in m. 5; C-F in m. 6), and combining the beginning sixteenth/dotted-eight/sixteenth rhythmic figure with the G-Ab-G neighbor figure in mm. 1-2 to stand as the last three notes of m. 5 (transposed to F-G-F in m. 6). One could even argue that the half-step descents in the bass line of mm. 5-6 are developing the half-step descent in m. 2, especially since they both move at the pace of the half note.

Figure 3a. Chopin, Etude in C Minor Op. 10/12, mm. 11-18

In Figure 3b, the development can be traced to the E-D#-E lower-neighbor figure on beat 2 of measure 1 in the basic idea, which is transposed and shifted to begin on beat 1 in measures 5-7, while the sixth from E up to C# in measure 1 (embellished by an octave leap) is transposed and filled in with a triadic arpeggiation in measures 5-7 (C#-E-A in m. 5; B-D#-G# in m. 6; A-C#-F# in m. 7).10

Figure 3b. Bach, Prelude in C# Minor from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, mm. 1-8

In Figure 3c, the development can be traced to the syncopated rhythm of measure 1, which is echoed in measures 9 and 11 (each of the eighth notes in measure 1 is split into a pair of sixteenths in the continuation); to the linear descent through a fifth, A-G-F#-E-D in measure 1 (the G supplied by the trill on F#), which recurs transposed in measures 10 and 12; and to the lower-neighbor motive in measure 2, which recurs transposed up a fifth in measure 9 and up an octave in measure 11.

Figure 3c. Bach, Partita No. 4 in D Major, mm. 1-16 (proportions doubled)

There is a variety of opinions about how cadences relate to sentence structure; these different opinions are typically reflective of the repertoire under examination. Caplin’s definition of the sentence requires a harmonic cadence; however, because Caplin’s goal is to explain the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, he limits his definition of cadences to half cadences and authentic cadences with both cadential chords in root position.11 Schoenberg included examples of the sentence from the Baroque and the Romantic periods, and therefore used a broader definition of cadential types, writing “the end of a sentence may close on I, V, or III, with a suitable cadence: full, half, Phrygian, plagal; perfect or imperfect; according to its function.”12 Matthew BaileyShea, in his dissertation on the sentence in Wagner, writes:

The simplicity of cadence options in the tightly knit themes of the classical period does not necessarily reflect the different options that arise in other historical contexts. In the music of Wagner, for example, deceptive or evaded cadences often stand in for traditional cadences on either tonic or dominant. Moreover, sentences in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century contexts will often end with nothing more than a slackening of energy leading to a point of repose.13

The current study still requires that the cadential idea of a sentence feature some kind of harmonic arrival, but recognizes not only perfect authentic and half cadences, but also deceptive, plagal, and the full spectrum of imperfect authentic cadences as representative of such an arrival.

Schoenberg described the purpose of the internal repetition in the sentence as “immediate intelligibility” and drew a comparison between classical and popular music by stating, “the classical masters … sought a ‘popular touch’ in their themes.”14 Indeed, sentence structure describes the melodic construction of a variety of examples from popular music. Figure 3d, John Williams’ Superman Theme, is a clear example of a simple sentence. The theme not only features the expected internal proportions but also develops a motive from the basic idea in its second half. In this case the development can be traced from the initial ascending octave leap from G4 to G5 (passing through C on the downbeat of m. 1) to the major seventh leaps up to B in measures 5 and 6 of the transcription, a connection that is highlighted by the retention of the three-note pick-up gesture and the strong dotted half notes on beat 1 in measures 2, 5, and 6. While the sentence is not commonly associated with any era as much as the Classical period, it has been widely used since the Baroque period, and more importantly, patterns of phrase organization that are best understood in terms of the sentence are abundant. Figure 4 provides lists of simple sentences from the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic eras, as well as from popular music.

Figure 3d. John Williams, Theme from Superman, the motion picture

Figure 4a. Simple sentences from the Baroque Era

Bach, English Suite in A Major, Bourrée* (repeated w/ variation to form a double period)

Bach, English Suite in E Minor, Sarabande

Bach, English Suite in E Minor, Passepied I* (repeated w/ variation to form a double period)

Bach, French Suite in B Minor, Menuet (repeated w/ variation to form a double period)

Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, Prelude in F# minor*

Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, Prelude in G# minor*

Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II, Prelude in Eb major

Bach, The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book II, Prelude in G# minor

Bach, Partita No. 1 in Bb Major, BWV 825, Menuet (repeated w/ variation to form a period)

Bach, Partita No. 2 in C Minor, BWV 826, Sarabande

Bach, Partita No. 3 in A Minor, BWV 827, Burlesca

Bach, Partita No. 3 in A Minor, BWV 827, Gigue*

Bach, Partita No. 5 in G Major, BWV 829, Courante

Bach, Partita No. 6 in E Minor, BWV 830, Toccata

Bach, Prelude in C Major, BWV 933

Corelli, Concerto Grosso 6/3, I, Largo

Corelli, Concerto Grosso 6/10, VI, Minuetto Vivace (presentation and continuation repeated)

Handel, Concerto Grosso in E Minor, Op. 6/3, III

Handel, Concerto Grosso in F Major, Op. 6/9, VI (continuation repeated)

Handel, Erste Sammlung, Keyboard Suite No. 7 in G Minor, Allegro

Handel, Halle Sonata No. 1 in A Minor, HWV 374, IV

Petzold, Minuet in G, Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach (repeated w/ var. to form a dbl. per.)

Scarlatti, D, Keyboard Sonata in A minor, K 54*

Scarlatti, D. Keyboard Sonata in C, K 95

Scarlatti, D. Keyboard Sonata in D minor, K 64

Scarlatti, D. Keyboard Sonata in D, K 490

*basic idea is repeated in another voice (imitative texture)

Figure 4b. Simple sentences from the Classical Era

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 2/1, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 52a, our Example 1)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 2/3, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 52b; continuation repeated)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 10/1, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 52c)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 31/2, III

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 49/1, III

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 57, I

Beethoven, Bagatelle, Op. 119/1

Beethoven, Symphony No. 1, I, mm. 53-68 (S theme; repeated w/ var.)

Beethoven, Symphony No. 1, III

Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, I, mm 6-21

Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 2, III (repeated w/ variation to form a period)

Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 3, I

Clementi, Sonatina, Op. 36/1, I

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 23, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58e; continuation repeated)

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 27, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58a)

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 27, III (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58b)

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 30, III (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58c)

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 34, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58h)

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 41, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58f; with hypermetrical elision)

Haydn, String Quartet in D Minor, Op 42, I

Mozart, Sonata for Keyboard, Violin (or Flute), and Cello, K. 12, I

Mozart, Concerto for Flute and Harp, K. 299, I, mm. 7-14

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 311, III (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59e)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 330, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59f)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 330, III (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59g)

Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 333, mm. 39-46, I

Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 333, mm. 65-72, I

Mozart, Bb Divertimento, K. 361/370a, I, mm. 19-26

Mozart, Symphony No. 25, IV

Mozart, Piano Concerto K. 467, I

Mozart, Le Nozze di Figaro, Act I, Scene 1, mm. 2-9

Figure 4c. Simple sentences from the Romantic Era

Brahms, 16 Waltzes for Piano, Four Hands, Op. 39, No. 4

Brahms, 16 Waltzes for Piano, Four Hands, Op. 39, No. 10

Brahms, Violin Concerto, Op. 77, I, mm. 206-213 (second theme)

Brahms, Violin Sonata, Op. 79, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 61d)

Brahms, Symphony No. 2, I, mm. 82-97 (second theme)

Chopin, Sonata No. 1 in C Minor, II

Chopin, Sonata No. 1 in C Minor, IV

Chopin, Sonata No. 2 in Bb Minor, I, mm. 9-24 (first theme)

Chopin, Waltz in C# Minor, Op. 64/2

Chopin, Nocturne in Bb Minor, Op. 9/1

Chopin, Nocturne in B Major, Op. 32/1

Chopin, Etude in A Minor, Op. 25/11, mm. 5-12

Dvořák, Symphony No. 9, II, mm. 46-49 (second theme)

Grieg, Piano Concerto, I, mm. 7-18 2-2 (continuation repeated)

Liszt, Ce qu’on entend sur la montagne, mm. 3-10

Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto in E Minor, I, mm. 132-147 (S theme, repeated w/ var.to form a dbl. period)

Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto in E Minor, III, mm. 9-12 (repeated w/ var. to form a dbl. period)

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 4, I, mm. 132-147

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 4, II, mm 36-42 (repeated w/ variation)

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 4, III, mm. 77-92

Mendelssohn, Symphony No. 5, IV, mm. 71-79

Schubert, Piano Sonata, Op. Post., IV (Schoenberg’s Ex. 60c)

Schubert, String Quartet, Op. 125/1, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 60g)

Schubert, Die Schöne Müllerin, "Das Wandern"

Schumann, Symphony No. 2, II, mm. 1-12 (continuation repeated w/ variation)

Schumann, Symphony No. 2, IV, mm. 31-46 (repeated w/ var. to form a dbl. period)

Schumann, Symphony No. 4, I, mm. 42-49

Schumann, Symphony No. 4, I, mm. 83-86

Schumann, Symphony No. 4, II, mm. 3-10

Schumann, Symphony No. 4, III, mm. 1-16

Schumann, Op. 25/1, "Widmung," mm. 14-29 (B section)

Schumann, Op. 25/16, “Räthsel”

Schumann, Op. 42/7, “An meinem Herzen”

Tchaikovsky, Symphony No. 6, I, mm. 89-100 (continuation repeated)

Wagner, In das Album der Fürstin M., mm. 9-16

Figure 4d. Simple sentences from popular music

Koehler/Arlin, "Let's Fall in Love"

Smith/Bernard, "Winter Wonderland"

Mac Davis/Billy Strange, "A Little Less Conversation"

Ellington/Strayhorn, “Satin Doll”

Stephen Foster, "Camptown Races"

Stephen Foster, "Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair"

Julius Fuik, “Entrance of the Gladiators” (“Thunder and Blazes”)

George Gershwin, "But Not For Me"

George Gershwin, "Let's Call The Whole Thing Off"

Rodgers/Hart, "You Took Advantage of Me"

Menken/Ashman, “Beauty and the Beast”

Michael Jackson, "Beat It" (verse)

Billy Joel, "The Longest Time"

Isham Jones, "It Had to Be You"

John Lennon, "All You Need is Love" (verse, mixed meter)

John Lennon, "All You Need is Love" (chorus)

Lennon/McCartney, "Eight Days a Week"

Lennon/McCartney, "Got to Get You into My Life"

Lennon/McCartney, "Ticket to Ride"

Klemmer/Lewis, "Just Friends"

Jerry Lee Lewis, "Great Balls of Fire"

Brian Wilson/Mike Love, “Help Me Rhonda”

Bruno Mars, "The Lazy Song"

Cole Porter, "Night and Day"

Prince, "Take Me With U"

Michael Shea, “Notre Dame Victory March”

Paul Simon, "Afterlife" (verse)

Stevie Wonder, "My Cherie Amour"

U2, "All I Want is You"

Sentences with Delayed Fragmentation or No Fragmentation

The nature of development in the continuation provides an interesting point of comparison for different types of sentences. Erwin Ratz writes, “the eight-measure sentence … contains a certain forward-striving character due to the increased activity and compression in its continuation” and the majority of Schoenberg's own examples do indeed feature this increased activity.15 However, Schoenberg himself wrote that “the continuation is a kind of development” and that development “implies growth, augmentation, extension, and expansion” in addition to “reduction, condensation, and intensification.”16 The next three sentence types address these various possibilities.

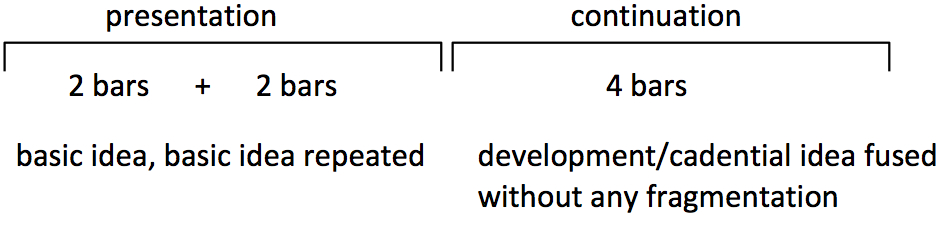

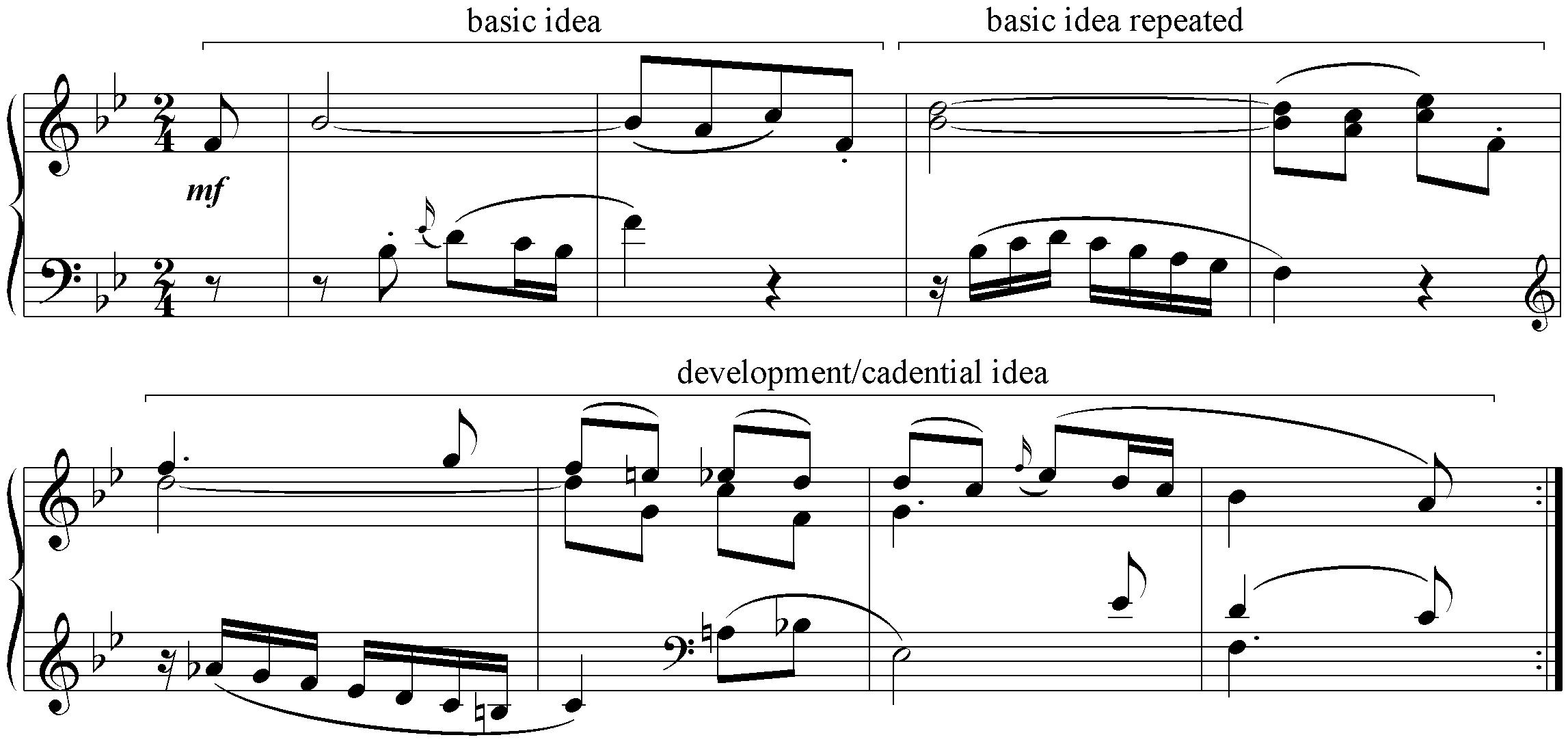

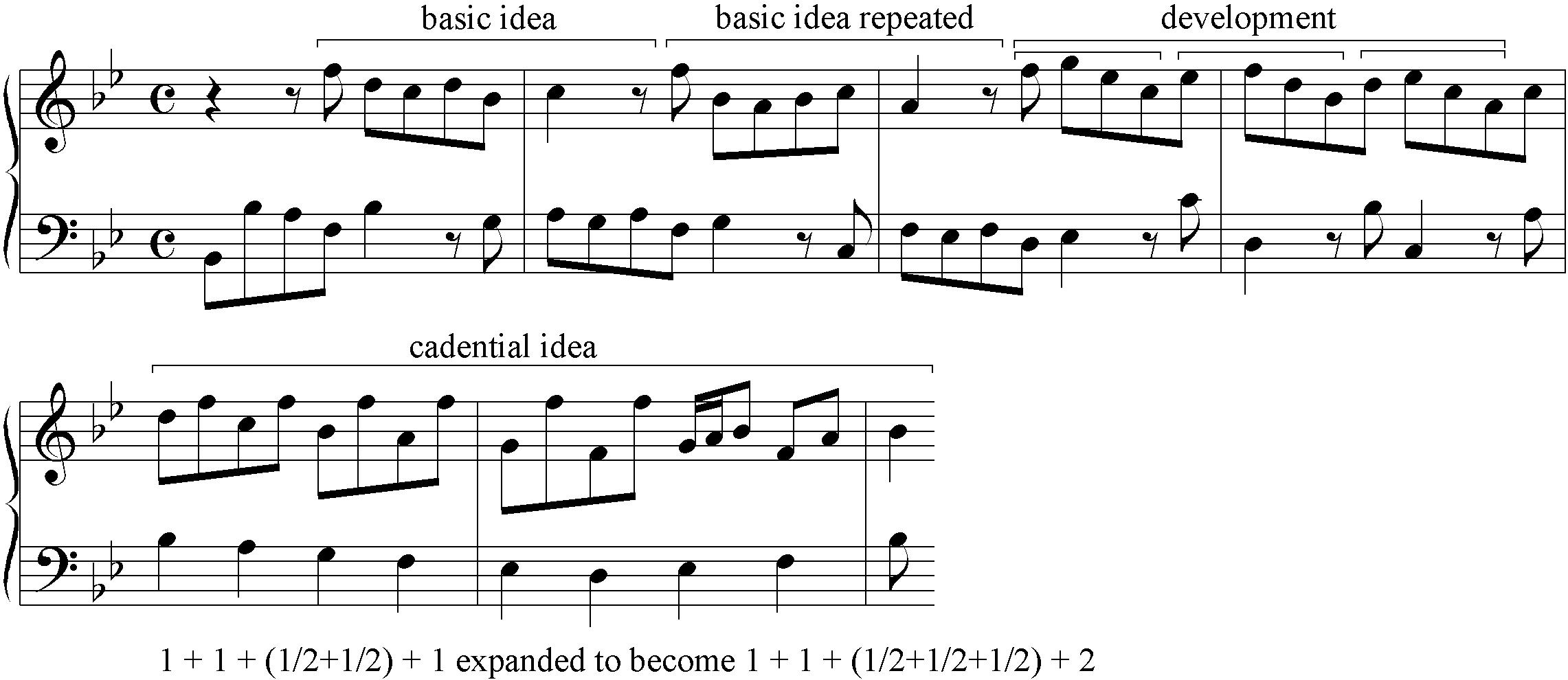

Sentences with delayed fragmentation or with no fragmentation, hereafter referred to as “DF/NF sentences,” are those in which the continuation does not begin with fragmentation. The two subtypes within this type are distinguished from each other by whether fragmentation occurs at all. In the first subtype, sentences with delayed fragmentation (“DF sentences”), shown in Figure 5a, fragmentation does indeed occur, but does not begin immediately after the repetition of the basic idea as it does in a simple sentence. Figures 6a and 6b illustrate DF sentences. Figure 6a, quoted from Schoenberg’s list of examples, shows a clearly articulated 2 + 2 presentation of the basic idea. However the continuation, while demonstrating both developmental and cadential functions, doesn't begin with fragmentation as the simple sentences discussed earlier do. In a simple sentence, the sense of development at the beginning of a continuation is usually created by both melodic fragmentation and harmonic acceleration that occurs immediately after the presentation is concluded. In Figure 6a, however, we do not get melodic fragmentation until measure 6, when a series of two-note slurs begins; the accompanying harmonic acceleration moves abruptly from the half-note rhythm established in measures 1-5, to a quarter-note chord on beat one of measure 6, to two eighth-note chords at the end of the bar, blurring the developmental and cadential functions. The two-note slurs in measure 6 are half step descents and can thus be traced to the 4-3 suspension in measure 2 of the basic idea.

Figure 5a. Model for sentence with delayed fragmentation (DF sentence)

Figure 5b. Model for sentence with no fragmentation (NF sentence)

Figure 6a. Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 41, II, quoted from Schoenberg's Ex. 58g (DF sentence)

Figure 6b illustrates another DF sentence. In the opening to Chopin's B Minor Waltz, the continuation begins as though it will be yet another two-bar iteration of the basic idea, but the fragmentation that usually occurs at the beginning of a continuation is simply delayed until measures 6-7, when the diminished-seventh leap into beat three of measure 6 is answered by a major-sixth leap in measure 7; the fact that there is no harmonic acceleration at all adds to the sense that developmental and cadential functions are seamlessly fused here. The "DF" label might be misleading here, because while one does hear fragmentation in measures 6-7, one also hears expansion as a developmental strategy before that: measure 5 sounds like a near-inversion of measure 1, with the upper neighbor G# in measure 1 turned into the lower neighbor E# in measure 5, the descending fourth in measure 1 answered by the ascending fourth in measure 5, and the descending third in measure 1 answered by an ascending third in measure 5. The expansion takes place as the final note of the basic idea is prolonged by the large intervals found in measures 6-7. The fragmentation process in this case does not isolate fragments of the basic idea to transpose, but rather splits a longer note value up into smaller ones. Also note how the A# in measure 2, leading tone in B minor, is answered in measure 6 by E#, leading tone to the dominant of that key.

Figure 6b. Chopin, Waltz in B Minor, Op. 69, No. 2, mm. 1-8 (DF sentence)

In the second subtype, sentences with no fragmentation (“NF sentences”), modeled in Figure 5b, the development of the basic idea is achieved through expansion rather than fragmentation. Figure 6c illustrates a sentence from the twentieth century with no fragmentation at all: development is achieved, instead, through expansion.

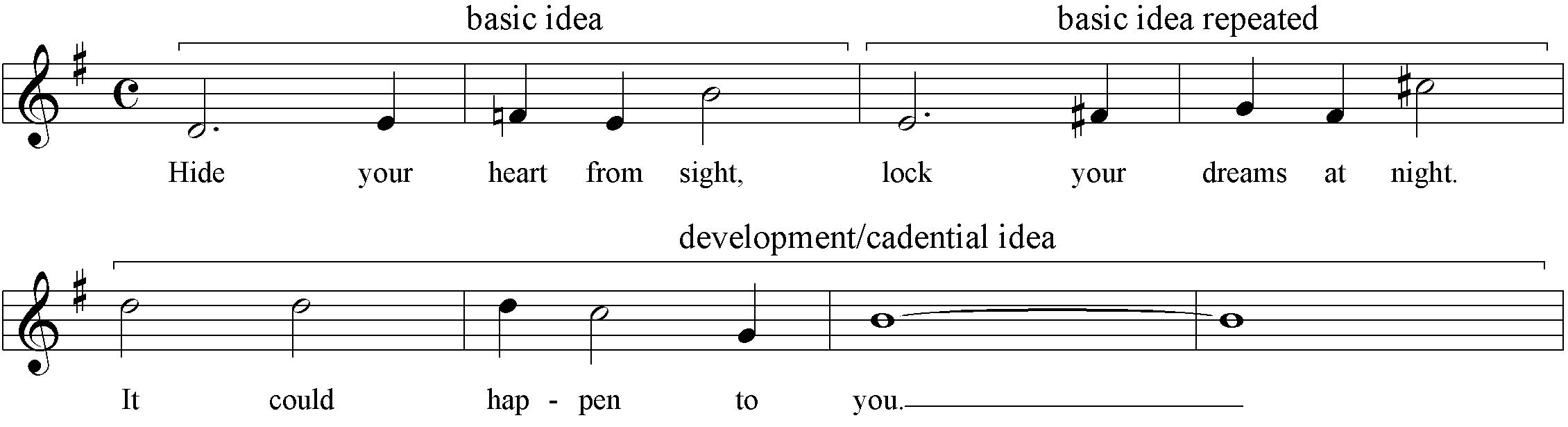

Figure 6c. Burke/Van Heusen, "It Could Happen to You" (NF sentence)

In “It Could Happen to You,” both the text and music of the continuation reinforce hearing it as an expansion of the basic idea. In the second line of the example, the text answers the question of why you should "hide your heart from sight" and "lock your dreams at night" ("it could happen to you"), and the music retains the proportions of the basic idea (two notes in the first bar and three notes in the second bar). Measures 5-8 also retain some of the basic idea’s characteristic intervals: the descending step that begins measures 2 and 4 also begins measure 6; and the leaps that follow that step by perfect fifth up in measures 2 and 4, are answered by a leap down by perfect fourth in measure 6. While NF sentences do not develop the basic idea through fragmentation, they still have much in common with the simple sentence: they have a presentation in which the basic idea is presented and then repeated, the basic idea and its repetition are the same length, and the presentation is followed by an equally long continuation that has both developmental and cadential functions. Figure 6d provides a list of other DF/NF sentences.

Figure 6d. Other DF/NF sentences

Handel, Concerto Grosso in D Major, Op. 3/6, II NF

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 14/2, I DF

Beethoven, String Quartet, Op. 18/1, I DF

Beethoven, Symphony No. 4, III, mm. 91-106 (trio) NF

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 28, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58d) NF with hypermetrical elision

Haydn, Piano Sonata No. 31, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 58i) NF

Mozart, Violin Sonata in A, K. 402, I NF

Mozart, String Quartet in A, K. 464, II NF

Mozart, String Quartet in C (“Dissonance”), K. 465, I DF

Mozart, Symphony in No. 25, I DF

Brahms, Cello Sonata, Op. 38, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 61a) NF

Chopin, Waltz No. 14 in Ab Major NF

Chopin, Waltz in F Minor, Op. 70/2 DF

Chopin, Nocturne in F# Major, Op. 15/2 DF

Chopin, Mazurka in F Major, Op. 68/3 DF

Chopin, Prelude in B Minor, Op. 28/6 NF

Schubert, String Quartet, Op. 161, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 60i) NF

Wagner, In das Album der Fürstin M., mm. 1-8 DF

Blake/Razaf, "Memories of You" NF

Van Heusen/Cahn, “Call Me Irresponsible” NF

George Gershwin, “S’Wonderful” NF

Rodgers/Hart, "My Funny Valentine" NF

Frank Loesser, “On a Slow Boat to China” NF

Lerner/Lowe, “Almost Like Being in Love” NF

Cole Porter, “You’re the Top” (chorus) NF

Heyman/Young, “When I Fall in Love” NF

Expanded Sentences

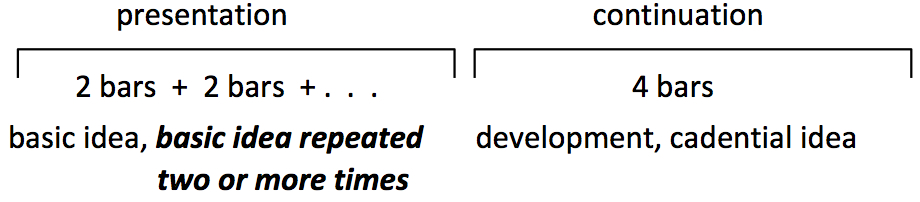

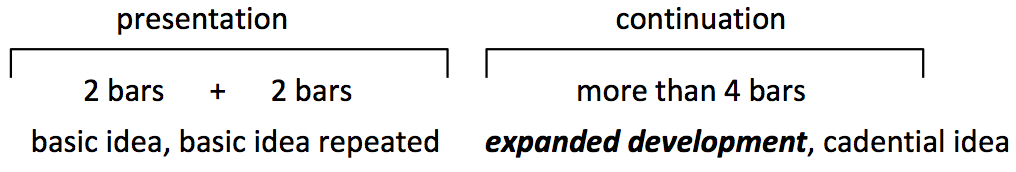

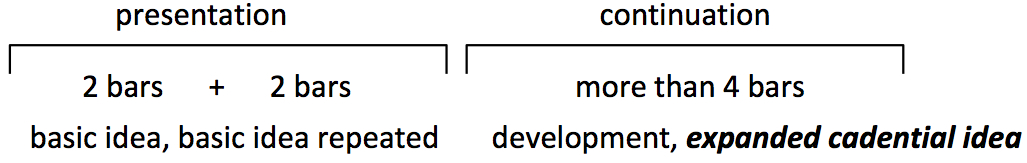

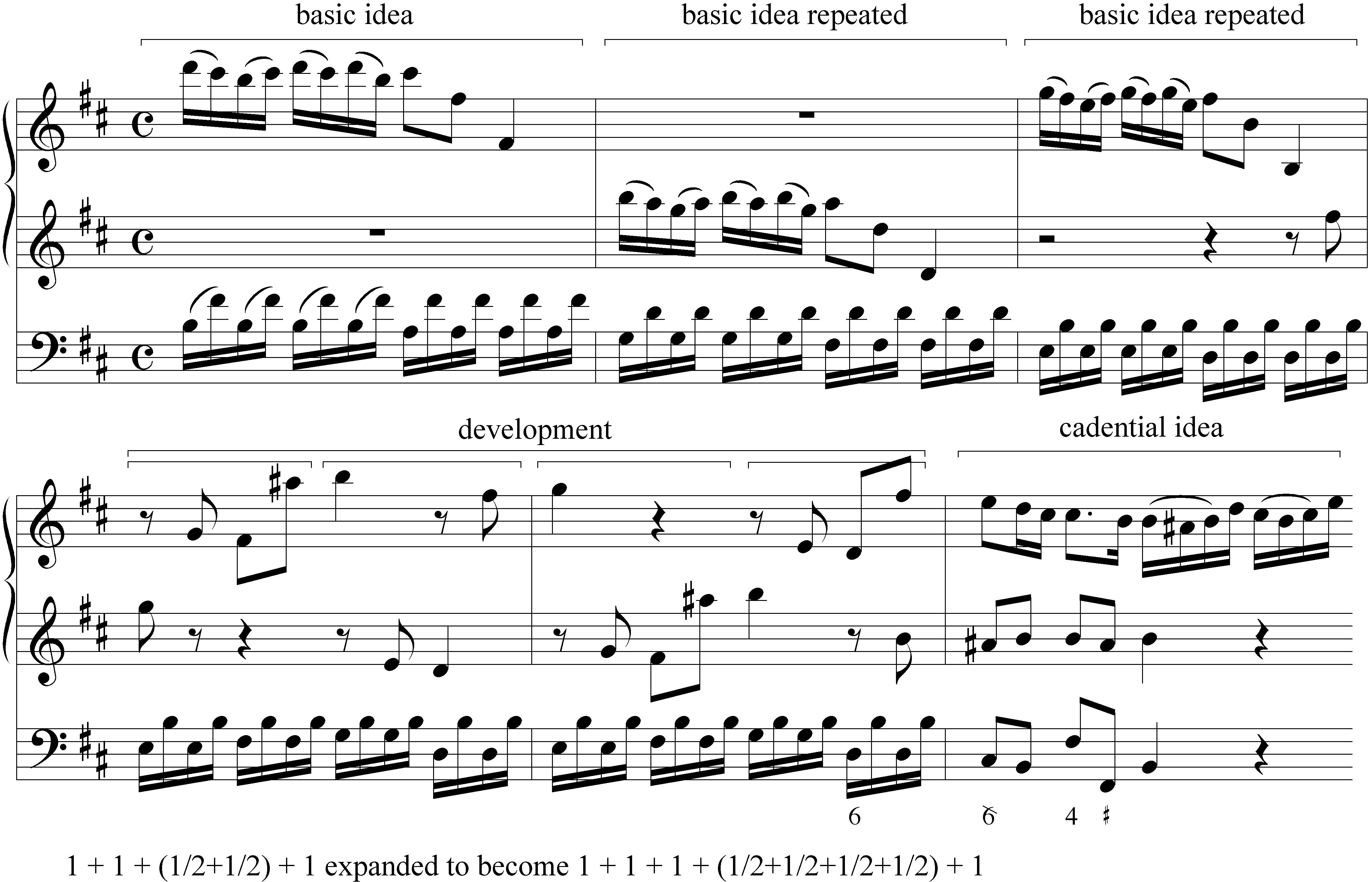

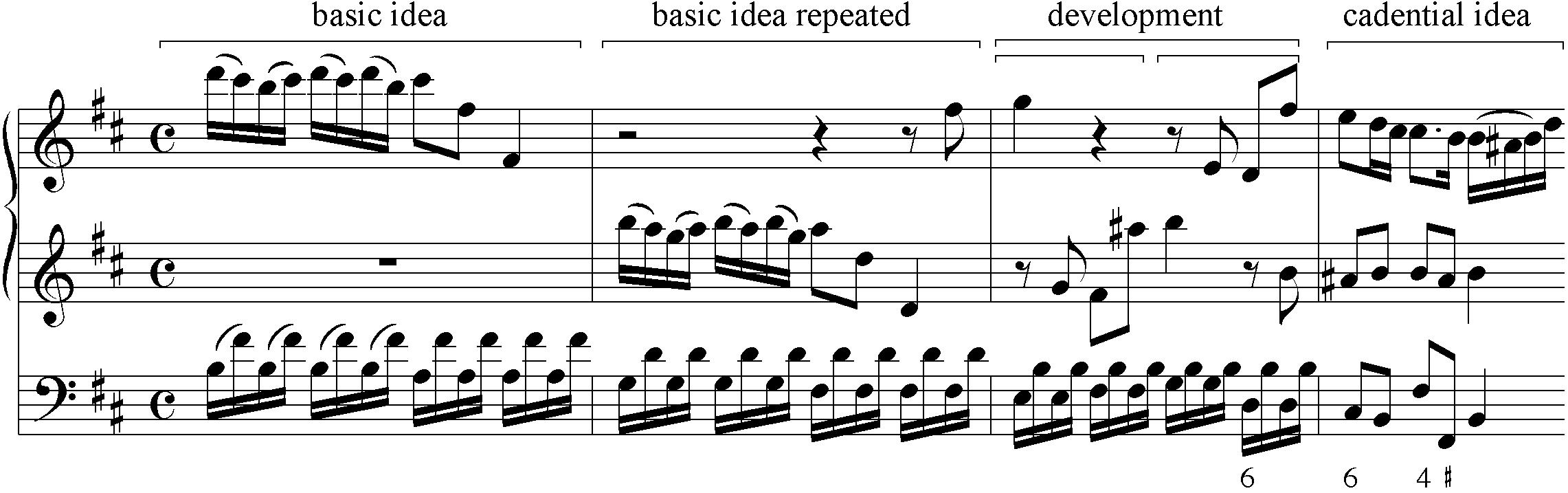

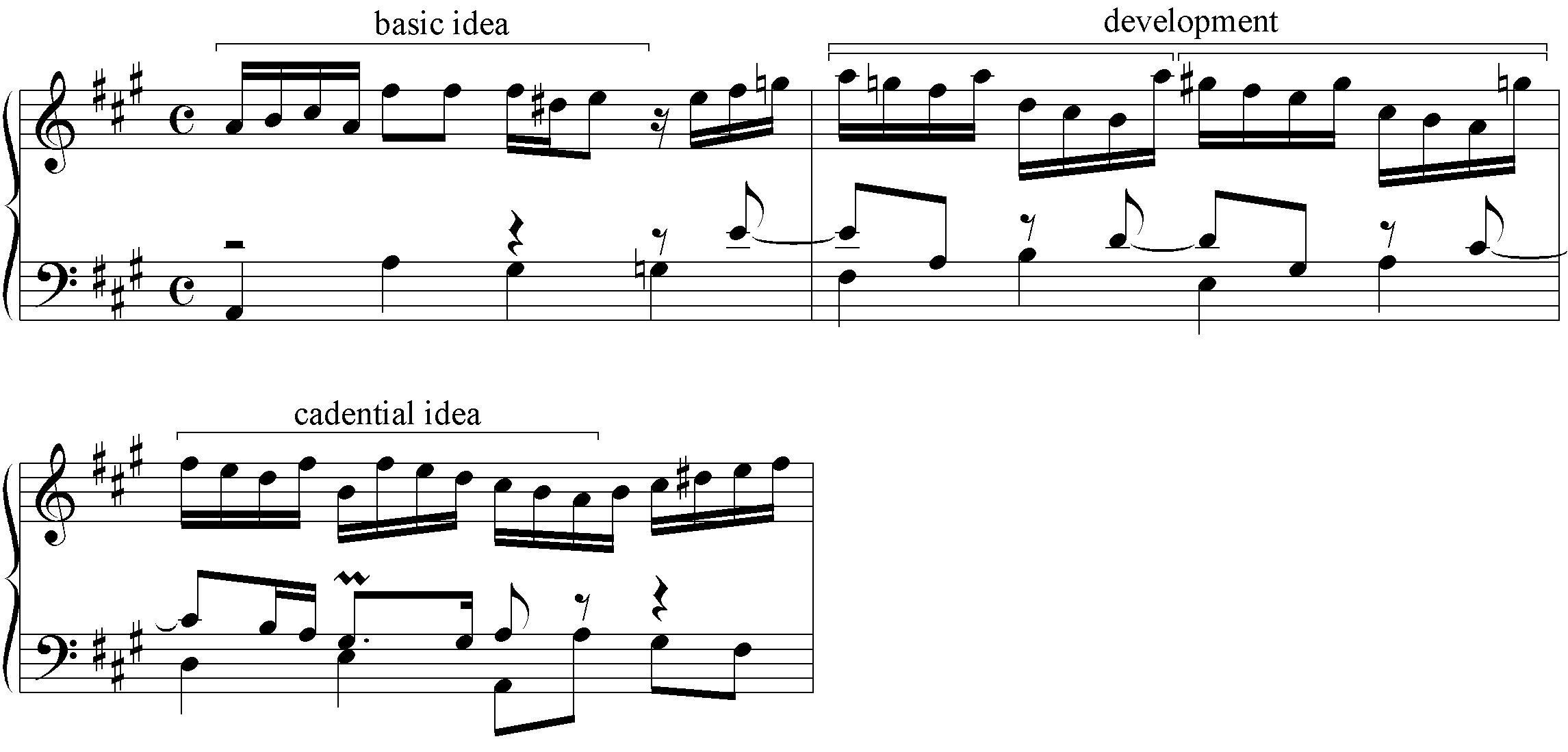

Expanded sentences are those that begin as simple sentences but contain added material. When material is added to the presentation, the addition takes the form of additional repetitions of the basic idea, as shown in Figure 7a.17 More often, material is added to the continuation, to either its developmental portion, its cadential portion, or both, as shown in Figures 7b and 7c. BaileyShea writes “it is not uncommon to have a continuation that stretches beyond the standard 1 : 1 : 2 proportions.”18 Hepokoski and Darcy have made a similar observation with respect to some first themes in sonata forms that they term “sentences with dissolving continuations.”19 In the opening to the third movement of Grieg's Piano Concerto, shown as Figure 8a, the composer added an extra measure to the cadential idea. The development in Figure 8a can be traced from the opening melodic rhythm (four sixteenths on beat 2, followed by two eighths on beat 1), the repeated descending half step motive in measures 12-13, and the contour of the head motive in the repetition of the basic idea – leap up, repeat, leap down – in measure 13. All of these elements are compressed into a two-beat span, which is immediately transposed in measures 15-17.

Figure 7a. Expanded sentence model with additional repetitions of the basic idea

Figure 7b. Expanded sentence model with a lengthened development

Figure 7c. Expanded sentence model with a lengthened cadential idea

Figure 8a. Grieg, Piano Concerto in A Minor, III, mm. 11-19

In the opening to Handel's Sonatina in B-Flat Major, shown as Figure 8b, there are additions to both the development and the cadential idea: the development is expanded by adding one more iteration of the eighth-note fragment, creating a total of three, and the cadential idea is expanded to become twice as long as one would expect given the otherwise orthodox sentence structure found in measures 1-4. Thus the expected model is expanded by adding an extra half measure of fragmentation and a double-long cadential idea. The development here can be traced from the metric position of the first four notes in measure 1 to the metric position of the beginning of the sequence in measure 3, from the embellished triadic descent (F-D-Bb) in measure 1 to the unembellished triad descent (G-Eb-C) in measure 3, and from the ascending whole step motive that ends the basic idea (C-D, Bb-C) to the whole step that begins the sequence in measure 3 (F-G). Figure 8c provides a sentence from Handel with an expanded presentation that features three iterations of the basic idea, and an expanded continuation that features double the amount of developmental material one would find in a simple sentence. The development here can be traced from the half-step motives (D-C# and C#-D) articulated by the bowings in measure 1 to the transposition of those motives in measures 4-5 (F#-G, G-F#, A#-B), and from the eighth-note arpeggio motive that ends the basic idea to the descending octaves (G-G) and twelfths (B-E) in measures 4-5 that are formed between the solo violins. This may not sound like a sentence compared to Classical-period examples, but note that this example not only maintains the characteristic sequence of functions (expository-developmental-cadential), but also begins the continuation with the same kind of fragmentation and harmonic acceleration that characterizes the simple sentence. Figure 8d provides a version of Handel's sentence recomposed to fit the simple sentence model to illustrate the underlying sentence structure in Handel's original. While this version sounds much more like what we generally think of as a sentence, it also sounds much less Baroque. Figure 8e lists other expanded sentences.

Figure 8b. Handel, Sonatina in B-Flat Major, mm. 1-7

Figure 8c. Handel, Concerto Grosso in B Minor, Op. 6, No. 12, Allegro, mm. 1-6

Figure 8d. Handel, Concerto Grosso in B Minor, Op. 6, No. 12, Allegro, mm. 1-6, recomposed

Figure 8e. Other expanded sentences

Bach, St. Matthew Passion, No.12, Aria (Schoenberg’s Ex. 57)

Bach, Two-Part Invention in C Major

Corelli, Concerto Grosso, Op. 6/9, IV Gavotta

Handel, Concerto Grosso in F Major, Op. 6/2, II*

Handel, Concerto Grosso in G Minor, Op. 6/6, V

Handel, Concerto Grosso in B Minor, Op. 6/12, II

Handel, Dritte Sammlung, Keyboard Sonatina in Bb Major

Handel, “L’empio, sleale, indegno”

Telemann, Concerto for Recorder, Strings, and Continuo, II Allegro

Telemann, Concerto for Recorder, Strings, and Continuo, IV Tempo di Minuet*

Vivaldi, Concerto for Violin in A, RV 353, I

Vivaldi, Concerto for Violin in A, RV 353, III

Vivaldi, Concerto for Violin and Strings in Eb, RV 253, Op. 8/5, I Presto*

*basic idea is repeated in another voice (imitative texture)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 10/2, I (Schoenberg’s Ex53b)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 27/2, III

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 31/2, I, mm. 21-41

Beethoven, Piano Trio in G, Op. 1/2, II

Haydn, Piano Trio in C, Hob XV:27, I

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59a)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 282, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59b)

Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 283, I (Schonberg’s Ex. 59c)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 310, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59d)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 333, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 59h)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 545, I

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 545, I, mm. 14-26 (second theme)

Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550, III

Brahms, Cello Sonata, Op. 38, I, mm. 58-65 (Schoenberg’s Ex. 61b)

Brahms, Cello Sonata, Op. 38, II (Schoenberg’s Ex. 61c)

Dvořák, Symphony No. 7, III

Liszt, Orpheus, mm. 72–84

Liszt, Prometheus, mm. 48-62

Schubert, String Quartet, Op. 125/1, I

Schubert, String Quartet, Op. Post, I (Schoenberg’s Ex. 60h)

Schumann, Op. 35/3, “Wanderlust”

Schumann, Op. 39/1, “In der Fremde”

Schumann, Op. 42/1, “Seit ich ihn gesehen”

Schumann, Dichterliebe, "Im wundershönen Monat Mai"

Bob Dylan, “Like a Rolling Stone” (verse)

Stephen Foster, “Beautiful Dreamer”

Hammerstein/Kern, “All the Things You Are”

Queen, “We Are the Champions” (chorus)

Truncated Sentences

Truncated sentences, modeled in Figures 9a-c, are those in which some element of the simple model has been omitted, but there is still at least 75% of the model present. For example, a truncated sentence might omit the repetition of the basic idea, or it might shorten either the development or the cadential material. The first seven measures of Mozart’s Overture to Le Nozze di Figaro, quoted in Figure 10a, introduce our discussion of truncated sentences. Schoenberg provided this opening as an example of how a sentence in a masterwork might deviate from the proportions of the practice form he gave. In the Figure, the basic idea is clearly articulated by the transposition of measure 1 to the level of the dominant in measure 3. Because measures 1-2 are heard as a single unit, measures 3-4 may be heard as a single unit, but this grouping is undercut by the fact that there are no rests after measure 3 and measure 5 is a varied transposition of measure 4. Nevertheless, the strong sense of cut time established in measures 1-4 would put a hypermetrical accent on the downbeat of measure 5, which is strong enough to mark it as a continuation. Therefore Figure 10a analyzes the passage with a truncated development as a 2 + 2 + (1) + 2.20 This is not to take away from the fact that other hearings are possible. One could also hear this as a truncated sentence in which the repetition of the basic idea is shortened by one bar, and in which the continuation actually starts in measure 4, yielding 2 + 1 + (1 + 1) + 2. In his discussion of this example, Schoenberg did not specify which interpretation he preferred, but did use it as an example of a sentence.

Figure 9a. Truncated sentence model with an omitted repetition of the basic idea

Figure 9b. Truncated sentence model with a shortened development

Figure 9c. truncated sentence model with shortened cadential material

Figure 10a. Mozart, Overture to Le Nozze di Figaro, quoted from Schoenberg's Ex.59i

Figures 10b and 10c provide clearer representations of truncated sentences. In each, the presentation does not repeat the basic idea before moving on to the continuation. The Air from Bach’s Orchestral Suite No. 3 begins with a two-measure basic idea. That idea is developed in measure 3 by shortening it from two measures to one measure, and then its condensed form in measure 3 is transposed down a step to become measure 4.21 Measures 5-6 feature a cadential idea, concluding the first section of this binary form. Except for the repetition of the basic idea, we have all the elements of a sentence.

Figure 10b. Bach, Air from Orchestral Suite No. 3, mm. 1-6

Figure 10c. Bach, Prelude in A Major from Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, mm. 1-3

The Prelude in A Major from Book I of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, shown in Figure 10c, has the same structure, only moving twice as fast: a one-measure basic idea is followed by a one-measure harmonic sequence that divides neatly in half, which in turn leads to a cadential idea. The development here can be traced from the sixteenth-note figure on beat 1 of measure 1 to the inversion of that figure on beats 1 and 3 of measure 3, and its varied repetitions on beat 2 and 4, and from the ascending sixth leap in measure 1 to the ascending seventh leaps in measure 3. In measures 4-6 (not shown), the same sentence structure appears at the level of the dominant with the parts inverted.

Figure 10c. Bach, Prelude in A Major from Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, mm. 1-3

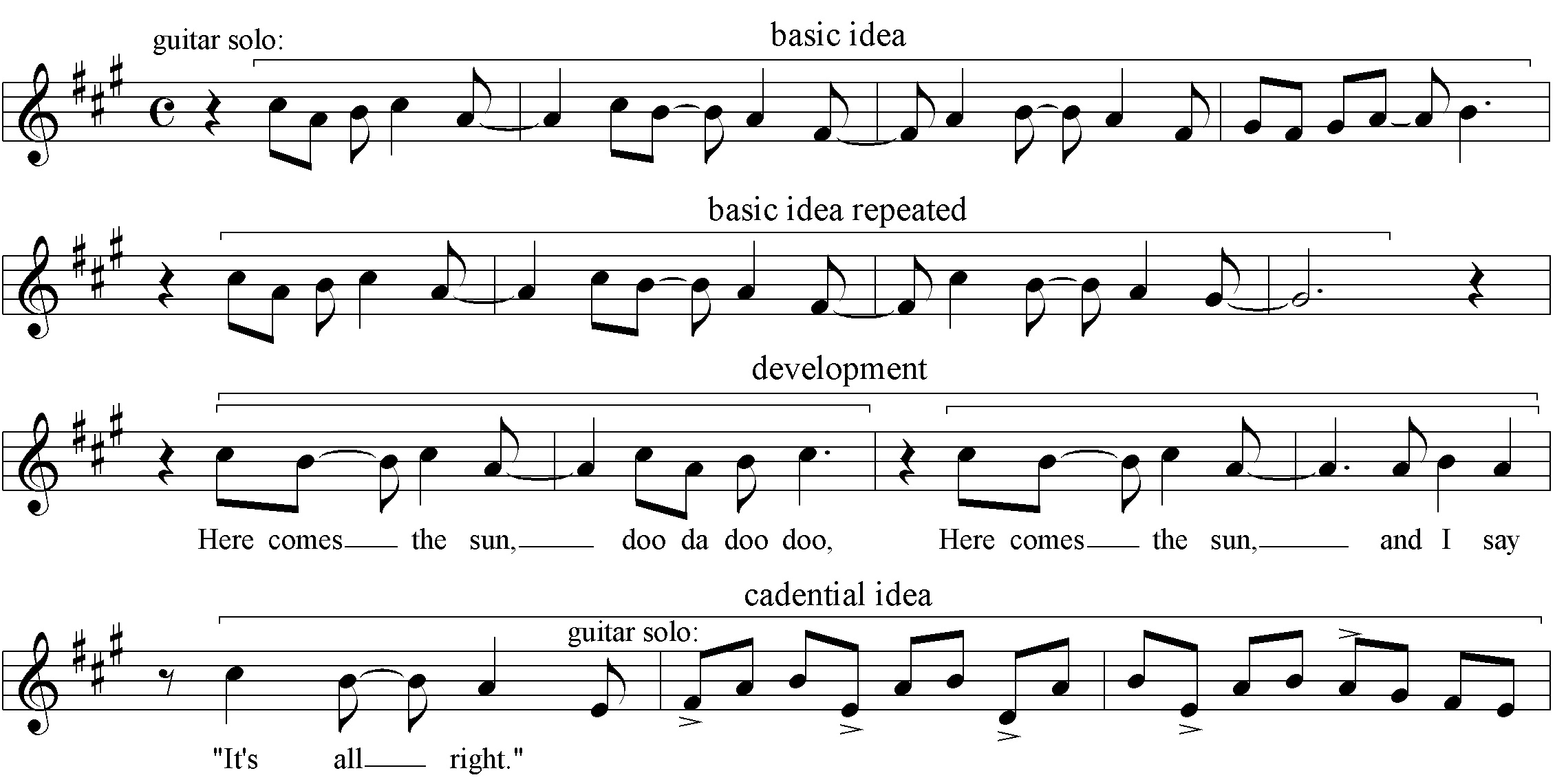

In Figure 10d, George Harrison uses a metrical shift to speed up the harmonic cadence, thereby condensing the expected four-bar cadential idea to three bars. Another way to interpret this example is to hear the final two bars of 4/4 as two bars of 6/8 and one bar of 2/4. Such a hearing would yield the more typical measure count, albeit compressed through meter changes.22 Figure 10e lists other truncated sentences.23

Figure 10d. Harrison, "Here Comes the Sun," mm.1-15, 4+4+(2+2)+3 (shortened cadential idea)

Figure 10e. Other truncated sentences

Bach, Bourrée from French Suite in E Major, mm. 1-12 (basic idea not repeated)

Bach, Partita No. 6 in E Minor, BWV 830, Courante (basic idea not repeated)

Handel, Concerto Grosso in D Minor, Op. 3/5, V (basic idea not repeated)

Handel, Concerto Grosso in G Minor, Op. 6/6, IV (basic idea not repeated)

Handel, Concerto Grosso in A Major, Op. 6/11, I (basic idea not repeated)

Handel, Concerto Grosso in A Major, Op. 6/11, IV (cadential idea is half as long as basic idea)

Scarlatti, D, Unpublished sonatas for the Spanish Royal family, XVIII Allegro molto (cadential idea is half as long as basic idea; basic idea is repeated in another voice)

Beethoven, Piano Sonata, Op. 2/1, III (Schoenberg’s Ex. 53a; development is half as long as expected)

Beethoven, Symphony No. 1, I, mm. 13-33 (P theme; continuation is shorter than expected)

Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, I, mm. 34-47 (P theme; development is half the expected length)

Mozart, Piano Sonata K. 282, mm. 1-4 (basic idea not repeated)

Haydn, String Quartet in Bb, Op 50/1, II (continuation is half the expected length)

Imitative Sentences

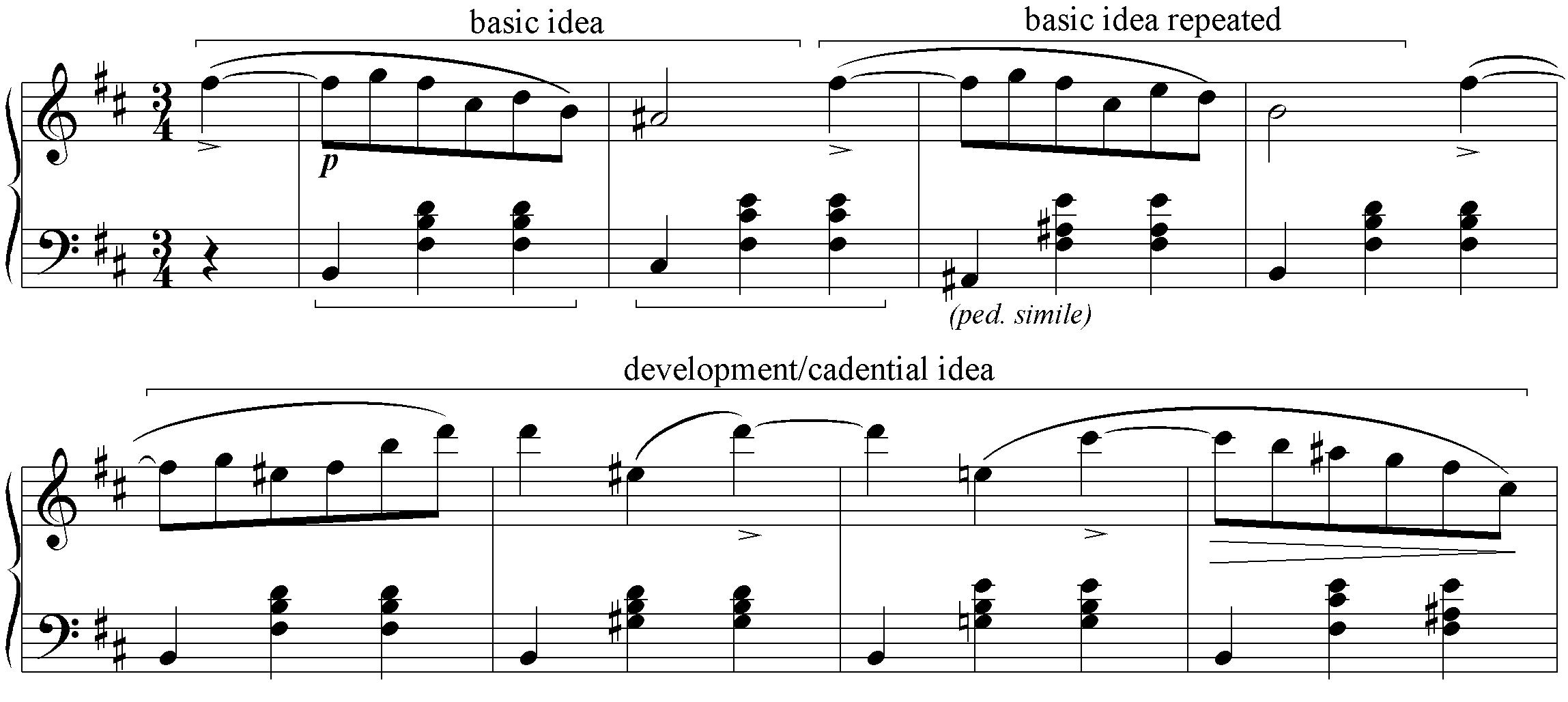

Finally, imitative sentences, modeled in Figure 11, are those in which the repetition of the basic idea occurs in another voice. This type of sentence structure is logically tied to the Baroque period, owing to that period’s predilection for imitative forms. The F#-Minor and G#-Minor Preludes from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, given as Figures 12a and 12b, both begin with a one-measure basic idea in the top voice that is then imitated by the bass voice in measure 2. This is followed in measure 3 by a harmonic sequence that neatly divides the measure in half and leads to a cadential idea in measure 4, that cadences on the downbeat of measure 5. The development in Figure 12a involves turning the ascending thirds of the basic idea into eighth notes and then juxtaposing them with the sixteenth-note figure that adorns each of its last three beats. The rhythm of each half measure also matches the composite rhythm of the first two beats of the basic idea. The development of the basic idea in Figure 12b involves simply shifting the first half of the basic idea up an octave and then changing its first descending leap from a third to a sixth.

Figure 11. Imitative sentence model

The imitative sentence as a type does not specify proportions, and must therefore be combined with other sentence types (e.g., expanded imitative sentences are common, particularly in the Baroque period). Figures 12a and 12b are simple imitative sentences. Other imitative sentences identified in this study have been listed in the appropriate categories and marked with an asterisk to show their imitative nature. For convenience, Figure 12c is a compilation of these examples into a single list. Sometimes imitation will be employed within the basic idea itself, as in the C#-Minor Prelude from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I (see Figure 3b). We choose not to call this an imitative sentence, since the sentence structure here could be identified solely by looking at the upper voice.

Figure 12c. Other imitative sentences

Bach, English Suite in A Major, Bourrée (repeated with variation to form a double period)

Bach, English Suite in E Minor, Passepeid I (repeated with variation to form a double period)

Bach, Partita No. 3 in A Minor, BWV 827, Gigue

Handel, Concerto Grosso in F Major, Op. 6/2, II (expanded)

Scarlatti, D, Keyboard Sonata in A Minor, K. 54

Scarlatti, D, Unpublished sonatas for the Spanish Royal family, XVIII Allegro molto (truncated)

Telemann, Concerto for Recorder, Strings, and Continuo, IV Tempo di Minuet (expanded)

Vivaldi, Concerto for Violin and Strings in Eb, RV 253, Op. 8/5, I Presto (expanded)

Previous Taxonomies of Sentence Structures

The taxonomy presented here is designed to be compatible with other taxonomies. Two useful elements from earlier taxonomies that complement the present one nicely deserve special mention: (1) the relationship between the basic idea and its repetition; and (2) the various ways in which sentences or portions of sentences take part in hybrid themes and compound themes, as defined by Caplin. Regarding the former, Schoenberg and Caplin enumerate three kinds of relationships between the basic idea and its repetition: exact repetition, sequential repetition, and complementary repetition (which Caplin renamed “statement-response repetition”). BaileyShea adds a welcome refinement by separating out the two different kinds of complementary repetition discussed by Schoenberg. BaileyShea uses “complementary repetition” to refer specifically to “any progression in which the basic idea begins on the tonic and the repetition returns to the tonic (I-V/V-I, I-ii/V-I, etc.).”24 He then uses Caplin's term “statement-response repetition” to refer to “any progression in which the basic idea begins on the tonic and the repetition ends on the dominant (I-I/V-V, I-ii/vi-V, etc.).”25 For example, Bach’s Prelude in C# minor (shown in Figure 3b) would be labeled as a simple sentence with a statement-response repetition of the basic idea.

Regarding Caplin's hybrid and compound themes, a similarly beneficial joining of taxonomies is possible. Caplin defines two different hybrid theme types that end with a sentential continuation: an “antecedent + continuation” and a “compound basic idea + continuation.”26 These could be used in combination with the present taxonomy by specifying whether the continuation is a simple, DF, or NF continuation.

Likewise, one could use the present taxonomy to provide greater specificity regarding what kinds of sentences or sentential elements are used in a compound theme. Caplin defines two different compound theme types: a “sixteen-measure period” and a “sixteen-measure sentence.”27 In all three subtypes of his sixteen-measure period, the antecedent ends with a continuation, so it could be used once again in combination with the present taxonomy by specifying whether the continuation is a simple, DF, or NF continuation. In the case of the sixteen-measure sentence, the present taxonomy could be an efficient tool for comparing these large sentences with smaller ones.28

The Beginning of a Historical Perspective

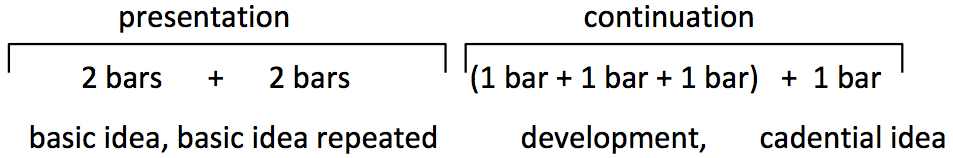

While we do not claim that the present study is exhaustive, and it may be premature to draw general conclusions about how the taxonomy of sentence structures presented here is represented in different styles, we do feel that our corpus of 214 examples is nevertheless substantial enough to suggest some trends that could perhaps be confirmed through further research. Figure 13 provides some noteworthy statistics regarding the 214 sentences discussed in this study, giving the number of each type of sentence in each style. Some trends suggested by our corpus of examples include the following: (1) the simple sentence is, by far, the most common type; (2) DF/NF sentences are rare in the Baroque, but commonly found in other styles; (3) the expanded sentence is not uncommon in most styles, but does not appear often in popular music; and (4) the truncated sentence is rare or non-existent in Romantic and popular music, but not so uncommon in Baroque and Classical music; (5) the imitative sentence is rare outside of the Baroque.

Figure 13. Analysis of the 214 sentences given in this study

The Length of a Sentence

Following Schoenberg’s example, the taxonomy presented here is flexible in recognizing sentences of different lengths.29 However, Schoenberg defined the basic idea as a collection of small motivic features and thus suggested size limits to the amount of melodic material that could be described as a basic idea.30 While the preceding examples follow these limitations, it is interesting to note that the basic design of a sentence can be observed on smaller and larger scales. Figure 14a, from Mozart’s K. 331, provides an example of a sentential design in which a single motive serves as the basic idea. Note how the entire sentence structure spans a single four-bar phrase which turns out to be the antecedent of a parallel period.31 At the other extreme, an entire phrase, consisting of an initial idea and a contrasting idea, can be seen as the basic idea of what might be called a hyper-sentence. Such is the case in the opening theme from Mozart's Symphony No. 40, given as Figure 14b. The use of the term “sentence” in describing Figures 14a and 14b captures the obvious similarities between these passages and what is more commonly heard as a sentence (such as the opening of Beethoven's Op. 2/1). Because the music in Figure 14a and 14b exceed Schoenberg’s concept of the basic idea, we have chosen not to include such examples in the current study; however, the existence of sentence-like patterns in formal units both smaller and larger than the eight-bar theme illustrates the usefulness of the design in organizing various levels of formal structure.

Figure 14a. Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 331, I, mm. 1-4

Figure 14b. Mozart, Symphony No. 40, I, mm. 2-20

In Conclusion

This article has focused primarily on sentences as they are found in music throughout the common-practice period and has proposed a taxonomy for explaining the full range of examples in terms of their internal proportions and formal functions. This taxonomy is divided into five sentence types: simple sentences, sentences with delayed or with no fragmentation, expanded sentences, truncated sentences, and imitative sentences. By including examples from popular music, we have suggested that this model is found even beyond the common-practice period. Along the way, two common post-Schoenbergian ideas about the sentence have been challenged: first, the idea that the proportions of a sentence are simply (2 x 2) + 4, as Ratz put it; and second, that the repetition of the basic idea is the single most important defining feature of the sentence. The suggested taxonomy of sentence structures has refined Schoenberg’s definition of the sentence while simultaneously broadening its potential application to a wider spectrum of musical styles, thereby increasing its utility as an analytical tool and allowing it to highlight commonalities within a much wider corpus of music.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Michael Berry, William Caplin, and Mark Anson-Cartwright for their invaluable help with earlier versions of this paper.

Notes

1Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 20-81. While Rothstein, Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music (1989), cites precedents for the sentence in one of Heinrich Koch's compound phrases and in Wagner's bar form, the reference to a sentence-like structure in Koch’s Introductory Essay (1983), is extremely brief, and the bar form in Wagner discussed by Lorenz in Das Geheimnis, is so loosely defined that the similarities it shares with the sentence are, as a consequence, trivialized. Schoenberg defined the sentence with enough previously unmarked details that it seemed appropriate to say that the concept started with him. For more on the relationship between the sentence and bar form, see BaileyShea, The Wagnerian Satz (2003).

2Frisch (1984) used the concept in his analyses of Brahms; Rothstein (1989) used the concept in his analyses of music by Haydn, Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Wagner; Caplin (1998) dedicated an entire chapter to Schoenberg's concept of the sentence and demonstrates its importance in the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven; BaileyShea (2003) examined the sentence in Wagner; Broman (2007) examined the sentence in Bartók; Martin (2010) and Krebs (forthcoming) both examine the sentence in Schumann; Vande Moortele (2011) examined the sentence in Liszt; Rodgers (2012) examined the sentence in Schubert; and Callahan (2013) assessed the role of the sentence in songs by Gershwin, Kern, Loewe, Porter, and Rogers.

3Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 60.

4Throughout this paper, we borrow the terms “presentation” and “continuation” from Caplin (1998).

5Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 63.

6Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 60.

7Richards (2011) has also established a taxonomy for the sentence. Because his work, like Caplin's, focuses on understanding the music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, a different taxonomy is introduced here, one that is tailor-made to encompass a wider range of examples.

8The former generalization is reflected in Kostka and Payne (2008); the latter generalization is reflected in Ratz (1973).

9The three functions (expository-developmental-cadential) recall the Vordersatz-Fortspinnung-Epilog (or Nachsatz) model for Baroque ritornellos, as first described by Wilhelm Fischer (1915) and later adapted by Dreyfus (1996).

10One could also argue that the rhythms of the upper voice in measures 5-7 are all an embellished rotation of measure 1: if one replaces the neighbor figure beginning each of the later measures with a dotted quarter, then exchanges the rhythms in the first and second half of each measure, one arrives at the same rhythm as measure 1 (but this observation discounts the tie on the latter measures).

11Caplin, Classical Form, 26-29 and 42-45. Richards (2011) argued that the cadential function is not necessary, and he made a compelling argument within the context of Caplin's theory of formal functions. However, plagal, deceptive, and other cadence types not recognized by Caplin abound in music before and after Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. If weaker kinds of cadences such as plagal and deceptive can serve a cadential function, then sentences that end without cadential functions are so few and far between that establishing a separate category for them seems unnecessary. Therefore this taxonomy retains the cadential requirement, only with a broader acceptance of what qualifies as a cadence.

12Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 59.

13BaileyShea, Wagnerian Satz, 63.

14Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 20.

15Ratz Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre, as quoted and translated in Caplin, “Hybrid Themes,” 152.

16Schoenberg, Fundamentals, 58.

17Richards (2011) labeled sentences with three iterations of the basic idea "trifold sentences" and sentences with four iterations of the basic idea "quadrifold sentences," respectively.

18BaileyShea, Wagnerian Satz, 49.

19Hepokoski and Darcy, Elements of Sonata Theory, 105-106.

20If one takes the continuation as starting in measure 5, the development can be understood as the process of transposing the first half of measure 2 to become the first half of measure 5, then transposing the second half of measure 4 to become the second of measure 5.

21The development here can be traced from the long note on the downbeat in measure 1, supported by a tenth that then descends by step in broken octaves, to a shortened form of that motive transposed up a third on the downbeat of measure 3, and from the flurry of sixteenth notes that begins after a strong beat in measure 2, and that features both a descending triadic arpeggiation (B-G-E) and a descending half step (D-C#), to a shortened form of that motive beginning in the second half of measure 3.

22The development here can be described as a fragmentation where the first five notes of the basic idea are mapped onto the first four notes of the development and again onto the next four notes of the development.

23One with an interest in popular music is likely to wonder whether or not a 12-bar blues structure – a a b, each phrase being four bars long – could be described in terms of the truncated sentence type. It could be, but the blues model doesn’t specifically call for the sense of acceleration one typically finds at the beginning of the continuation, so it would have to be understood as a hybrid of the NF sentence type and the truncated sentence type, and by eliminating both the characteristic proportions of the sentence and the sense of acceleration usually found in the continuation, it would be easy to argue that its relationship to Schoenberg’s practice form has been stretched to a breaking point. One could also argue that there is nothing to be gained by labeling the 12-bar blues as a “NF/truncated sentence,” since the term “12-bar blues” is a much more detailed descriptor than the hybrid sentence label, in that “12-bar blues” also specifies a harmonic structure.

24BaileyShea, Wagnerian Satz, 54.

25Ibid.

26Caplin, Classical Form, 59-63.

27Ibid., 63-70.

28For example, Caplin's Example 5.16 would be considered a truncated sentence according to this taxonomy, but his Example 5.17 would be a simple sentence in which the continuation is repeated. Caplin labels both of these as sixteen-measure sentences, and though he describes the differences between them in his prose, he does not establish a specific terminology that summarizes the difference.

29Most of Schoenberg's examples have basic ideas with 7-15 notes. Nine of his 37 examples (Examples 53b, 59c, 60d, 60e, 60g, 60h, 60i, 61a, and 61b) have shorter basic ideas. All but the first two of these are in his last set of ten examples, those by Schubert and Brahms, suggesting that Schoenberg considered these to be artful reinterpretations of the sentence concept rather than normative expressions of it.

30The relationship between basic ideas and motives in Schoenberg's thought is thoroughly explored in Carpenter (1983) and Schiano (1992).

31In discussing this excerpt, Caplin (1998, 51) wrote: “it would be inappropriate … to consider this four-measure unit a genuine sentence, since it does not contain sufficient musical content to make up a full eight-measure theme.” Richards (2011), however, was in favor of broadening the use of the term "sentence" to include a variety a functions beyond those of a theme, and so considered this passage to be a sentence.

Bibliography

BaileyShea, Matthew. The Wagnerian Satz: The Rhetoric of the Sentence in Wagner’s Post-Lohengrin Operas. Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 2003.

Beach, David. "Phrase Expansion: Three Analytical Studies." Music Analysis 14 (1995): 27-47.

Blombach, Ann. “Phrase and Cadence: A Study of Terminology and Definition.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 1 (1987): 225-251.

Broman, Per F. “In Beethoven’s and Wagner’s Footsteps: Phrase Structures and Satzketten in the Instrumental Music of Béla Bartók.” Studia Musicologica 48 (2007): 113–31.

Budday, Wolfgang. Grundlagen musikalischer Formen der Wiener Klassik: An Hand der zeitgenössischen Theorie von Joseph Riepel und Heinrich Koch dargestellt an Menuetten und Sonatensätzen (1750-1790). Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1983.

Callahan, Michael R. “Sentential Lyric-Types in the Great American Songbook.” Music Theory Online 19.3 (September 2013).

Caplin, William. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. London: Oxford University Press, 1998.

___________. “Hybrid Themes: Toward a Refinement in the Classification of Classical Theme Types.” Beethoven Forum 3 (1994): 151-165.

Carpenter, Patricia. “Grundgestalt as Tonal Function.” Music Theory Spectrum 5 (1983): 15-38.

Dahlhaus, Carl. “Satz und Periode: Zur Theorie der musikalischen Syntax.” Zeitschrift für Musiktheorie 9 (1978): 16-26.

Darcy, Warren. “Review of Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven by William Caplin.” Music Theory Spectrum 22 (2000): 122-125.

Dreyfus, Laurence. Bach and the Patterns of Invention. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Galand, Joel. “Formenlehre Revived.” Review of Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven by William Caplin.

Intégral 13 (1999): 143-200.

Fischer, Wilhelm. “Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des Wiener klassischen Stils.” Studien zur Musikwissenschaft 3 (1915): 24-84.

Frisch, Walter. Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth Century Sonata. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Krebs, Harald. Sentences in the Lieder of Robert Schumann: The Relation to the Text. Forthcoming.

Koch, Heinrich Christoph. Introductory Essay on Composition. Trans. and ed. by Nancy Kovaleff Baker. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

Kostka, Stefan and Dorothy Payne. Tonal Harmony, with an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.

Lorenz, Alfred. Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner. 4 Vols. Berlin: Hesse, 1924-1933.

Martin, Nathan. “Schumann’s Fragment.” Indiana Theory Review 28/1 and 2 (Spring and Fall 2010): 85-109.

Mathes, James. The Analysis of Musical Form. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.

Ratz, Erwin. Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formeprinzipien in den Inventionen und Fugen J. S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens. 3rd ed. Vienna: Universal, 1973.

Richards, Mark. “Viennese Classicism and the Sentential Idea: Broadening the Sentence Paradigm.” Theory and Practice 36 (2011): 179-224.

Rodgers, Stephen. “Sentences with Words: Phrase Structure and Poetic Structure in Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory in New Orleans, Nov. 2, 2012.

Rothstein, William. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer, 1989.

Santa, Matthew. Hearing Form: Musical Analysis With and Without the Score. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Schiano, Michael Jude. “Arnold Schoenberg's Grundgestalt and its Influence.” Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University, 1992.

Schoenberg, Arnold. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1967.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. “Cadential Processes: The Evaded Cadence and the ‘One More Time’ Technique.” Journal of Musicological Research 12: 1-51, 1992.

Vande Moortele, Steven. Two-Dimensional Sonata Form: Form and Cycle in Single-Movement Instrumental Works by Liszt, Strauss, Schoenberg, and Zemlinsky. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2009.

___________. “Sentences, Sentence Chains, and Sentence Replication: Intra- and Interthematic Formal Functions in Liszt’s Weimar Symphonic Poems.” Intégral 25 (2011): 121-158.