Abstract

More than a half a century after the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, significant areas of change have centered on (1) the growth of academic programs in ethnomusicology; (2) the expansion of professional organizations; (3) creation of new research areas; and (4) the impact of technology on global linkages and intersections. At the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, the early scholars could scarcely have anticipated some of the changes in the research and teaching areas within the discipline. Medical ethnomusicology, music and violence, gender issues, music and tourism, forensic ethnomusicology are all areas, among others that have created new venues for research as well as teaching. While ethnomusicology has expanded and increased its scope, the degree to which it has been institutionalized within the academy, particularly within the United States, is still somewhat limited. More than fifty years after the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, one of several professional organizations devoted to the study of ethnomusicology, there are very few departments of ethnomusicology. Thus, the growth of the field is balanced by challenges that pose considerable threat to the real institutionalization of ethnomusicology as a grounded and anchored field within the academy. These challenges come at a time when the academy itself is under considerable pressure to corporatize and emphasize scientific and translational research.

Ethnomusicology, as a field of inquiry, has evolved considerably since 1955, when the founders formed the professional association known as Society for Ethnomusicology. The second decade of the twenty-first century promises to be a time of accelerated changes. To understand how far the field has come, it is instructive to move back to the beginning of the flowering of ethnomusicology within the United States and consider what has happened up to this point.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, as scholars from musicology, anthropology, and related fields sought a way to collaborate in the emerging arena of scholarship where they worked, they consciously decided to form a new professional organization. They elected not to be a subgroup of the American Musicological Society or the American Anthropological Association.

With that move was born an area of inquiry that is today widely known and recognized within and outside of the academy. At that time, however, the very term ethnomusicology had only recently evolved from the hyphenated form “ethno-musicology” as used by Jaap Kunst in the Netherlands, and others. And that antecedent term had its ancestors in the field of comparative musicology or vergleichende Musikwissenschaft, which was centered in Berlin, Germany.

In the early years, ethnomusicology was defined as the music of the “other.” At Indiana University, George Herzog taught a course in Primitive Music. This could be music of Africa or Native America. But if we move down the road through time, ethnomusicology as it is practiced today encompasses the study of any music anywhere in the world. Popular music, religious music, and classical art music are all open for the ethnomusicologist’s gaze. Ethnomusicological research implies the study of music as culture in a situation where neither the sound nor the circumstances of creation dominate the focus of the ethnomusicology. The research centers on the study of the process of creating meaning of many kinds through music and the importance of understanding that meaning through ethnographic study or face-to-face encounters with the music makers and audience members.

More than a half a century after the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, significant areas of change can be discerned. These developments have centered on (1) the growth of academic programs in ethnomusicology; (2) the expansion of professional organizations; (3) creation of new research areas; and (4) the impact of technology on global linkages and intersections.

These developments have emerged against the backdrop of some challenges that are certain to affect the future as ethnomusicology approaches a century of existence within the United States and across the globe. If we thread our way through some of the dimensions of the developments as well as the potential challenges, then we can anticipate some of the outlines of the possible future for ethnomusicology.

Growth of Academic Programs in Ethnomusicology

During the last half century, many universities and colleges around the world began to offer courses in ethnomusicology. Typically, these classes started with an introductory World Music or a Javanese dance course. Later, when schools hired trained ethnomusicologists to teach the courses regularly, the variety of courses expanded. Early on these were labeled by world area: Music of West Africa, Dance of South Asia, or Folk Music of North America. Geographic area dominated the way ethnomusicology was delineated. Within ethnomusicology courses, stylistic analysis as well as cultural context constituted focal areas of instruction.

Music performance developed as another important area of instruction within the United States, particularly at schools like UCLA, Wesleyan, and Michigan. At these schools students studied with master artists who often came for extended residences. At UCLA, Mantle Hood began with Javanese gamelan from Southeast Asia but quickly added ensemble instruction from West Africa, South Asia, and East Asia among others. Today the UCLA performing ensembles are described more inclusively:

Its performance ensembles represent musical cultures from all corners of the world, including music of Bali, the Balkans, Brazil, China, Ghana, Korea, Mexico, the Near East, and the U.S. (African-American music).

http://www.schoolofmusic.ucla.edu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=846:world-music-at-ucla&catid=44&Itemid=224 (Accessed 4 September 2013)

Graduate work included additional courses like Seminar in Ethnomusicology, which emphasized theory and method in the context of studying music of any given geographic area. At Indiana University an expanded set of core courses included Transcription and Analysis, Paradigms in Ethnomusicology, History of Ideas (intellectual history), and Fieldwork. This emphasis was noted on the website:

At Indiana University, Ethnomusicology is a comprehensive and interdisciplinary program that emphasizes analytical, theoretical, and methodological training in ethnomusicology and ethnographic research.

http://www.indiana.edu/~folklore/ethno.shtml (Accessed 4 September 2013)

Major research universities, for the most part, offered the MA and PhD degrees with an emphasis in ethnomusicology. These were situated almost exclusively in schools and departments of music. One of the oldest programs in ethnomusicology grew up at Wesleyan University, which proclaims on its Welcome page to the Department of Music:

As an integral part of one of the nation's leading liberal arts institutions, the department has enjoyed an international reputation for innovation and excellence, attracting students from around the globe since the inception of its visionary program in World Music four decades ago.

http://www.wesleyan.edu/music/ (Accessed 4 September 2013)

Indiana University, where the study of ethnomusicology is centered in the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, developed as an exception to this pattern of embedding ethnomusicology within departments or schools of music. And despite the founders of the Society for Ethnomusicology being anthropologists as well as musicologists, few programs are centered outside of music departments and schools.

The integration of ethnomusicology with other aspects of music study varies enormously. In some schools, ethnomusicology is quite compartmentalized. In others, it is more intertwined. Notable is the co-listing of ethnomusicology and musicology at University of Texas at Austin in the Butler School of Music:

The Musicology and Ethnomusicology Division is unusual in American academic for its integration of musicology and ethnomusicology, history and ethnography; we encourage our students to challenge the shifting boundaries between Western “art” repertories. http://mbe187.music.utexas.edu/musethno/ (Accessed 4 September 2013)

The degrees offered are still in musicology or ethnomusicology, but the effort to integrate becomes evident. Indeed in other parts of the world, ethnomusicology may be quite central to the offerings related to music. At the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, for example, the program for the MA in Fine and Performing Arts focuses almost exclusively on local music: “Music studies concentrate mainly on the music of Tanzania and of East Africa.” http://idmmei.isme.org/index.php/institutions?pid=174&sid=2380:University-of-Dar-Es-Salaam-1-Dar-Es-Salaam (Accessed 4 September 2013)

The growth of academic programs in ethnomusicology for the last half century and more has reached the point where 72 study programs are listed by the Society for Ethnomusicology. http://www.ethnomusicology.org/?GtP (Accessed 4 September 2013)

These programs are but a portion of the programs around the world, which offer the MA, PhD and even BA in ethnomusicology.

Expansion of Professional Organizations

As courses in ethnomusicology proliferated, professional organizations also grew to enable a collaborative network of scholars. The Society for Ethnomusicology (SEM), founded in 1955, grew to a total of some 1800 individual and 821 institutional members. The membership has been gradually increasing at a time when some other academic professional institutions have been losing membership http://www.ethnomusicology.org/

(Accessed September 11, 2013).

As the membership has proliferated, so too have chapters, sections, and interest groups within the Society for Ethnomusicology. Ten regional chapters annually host meetings around the country for ethnomusicologists who live in geographic proximity. There are presently 11 sections, ranging from African music to Gender and Sexualities Taskforce to Section on the Status of Women. These sections have their own chairs, collect dues, run Listservs, host websites, and offer prizes. There are 16 special interest groups that range from Special Interest Group for Ecomusicology to Special Interest Group for Music and Violence, and Special Interest Group for Medical Ethnomusicology. (The interest groups constitute the first step toward becoming a section, even though some interest groups have retained that status for years.)

The Society for Ethnomusicology annual conference, held throughout the United States, several times in Canada, and once in Mexico City, attracts nearly 1,000 attendees. Significantly, a majority of the attendees are student members, signaling the large number of people who may become members in the future.

SEM hosts a website and many of the sections have their own websites. The organization publishes a journal, a newsletter, a student newsletter, and reviews of various types. These publications are both paper and digital, available in print and through the web.

Most significantly SEM has progressed from an organization run by volunteers to one staffed by two full-time professionals. In addition, a conference bureau takes considerable responsibility for running the annual meeting. Many volunteers support the efforts of the full-time staff.

Several other important ethnomusicology professional organizations complement SEM, including the International Council of Traditional Music, whose founding in 1948 pre-dated the Society for Ethnomusicology by several years http://www.ictmusic.org/ (Accessed September 11, 2013). This group, linked to UNESCO, is broadly international in representation and has some 19 study groups that hold meetings on focused topics. These interest groups range from Iconography in the Performing Arts, to Folk Music Instruments, and Applied Ethnomusicology, as well as Music and Minorities.

There is also the British Forum for Ethnomusicology (BFE), founded in 1973, that attracts members primarily from the United Kingdom and Europe, but which is also international in scope http://www.bfe.org.uk/ (Accessed September 11, 2013). Like the other professional societies for ethnomusicology previously mentioned BFE publishes a journal with broad distribution. It holds an annual conference as well as several smaller gatherings each year.

A number of organizations gather ethnomusicologists and other scholars who focus on music research particular areas of the world. These include The Society for Asian Music, The Association of Chinese Music Research, The Association for Korean Music Research, and the National Association for the Study and Performance of African-American Music.

Professional organizations play various roles in shaping and molding ethnomusicology worldwide. Their annual meetings provide the fora for faculty to present their most recent research for comments and discussion from fellow scholars. And it is these papers that are frequently then revised into the articles for the major publications of these societies. These meetings are also a venue for employers to interview prospective ethnomusicologists, for scholars to network with one another, for groups to plan projects together, and for publishers to display publications by ethnomusicologists.

Expansion of New Research and Teaching Areas

At the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, the early scholars could scarcely have anticipated some of the changes in the research and teaching areas within the discipline. Medical ethnomusicology, music and violence, gender issues, music and tourism, forensic ethnomusicology are all areas, among others that have created new venues for research as well as teaching.

One such area is forensic ethnomusicology. In the area of forensic ethnomusicology, for example, Portia Maultsby or Frederic Lieberman, have been called render a verdict regarding how similar two recordings of music are to one another. What has one musician taken from another musician’s work and to what extent are they different works? David McDonald has testified at a federal trial in the U.S. regarding the textual content of musical lyrics and their intent. The trial concerned suspected al-Qaeda members and their use of music to communicate their intentions.

Medical ethnomusicology, where ethnomusicologists and medical personnel often consult and collaborate for both research and practical application in therapy was the focus of a full day pre-conference at the 2013 annual meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology. One of the areas within medical ethnomusicology of particular attention has been the HIV/Aids epidemic in Africa. The volume documents the use of music as critical both to therapy and to communication about prevention (Barz and Cohen 2011).

Each of these new areas expands the study of music within various cultural contexts. These new areas show how music is critical to life events and situations. These new areas recognize that music is far more than just pleasure in many settings, and ethnomusicologists have been eager to explore these areas with ethnographic research.

Technology and Global Flows

The astonishing transformations in how music is transmitted and how it is preserved have been fundamental to how ethnomusicology as a discipline functions today. Just as the invention of the cylinder recorder was critical to the development of the study of music at the turn of the twentieth century, so too digital and computer technology is transforming the way that ethnomusicologists conduct their research and teaching. This technology revolution allows for access to the moving images of performers where sound and motion are easily apprehended as music is studied. The Smithsonian Folkways Video is one example of these scholarly publications that are part of the technological revolution. http://www.folkways.si.edu/explore_folkways/video_africa.aspx (Accessed September 4, 2013) Alexander Street Press has also amassed a collection of ethnographic video that can be accessed for teaching and research purposes. http://alexanderstreet.com/products/ethnographic-video-online (Accessed September 4, 2013)

During my own career I began using a reel-to-reel tape recorder (video as well as sound). Analog recordings were relatively awkward to study, manipulate, and to preserve. The notes I took were typed on a portable typewriter with carbon copies made to protect the original notes.

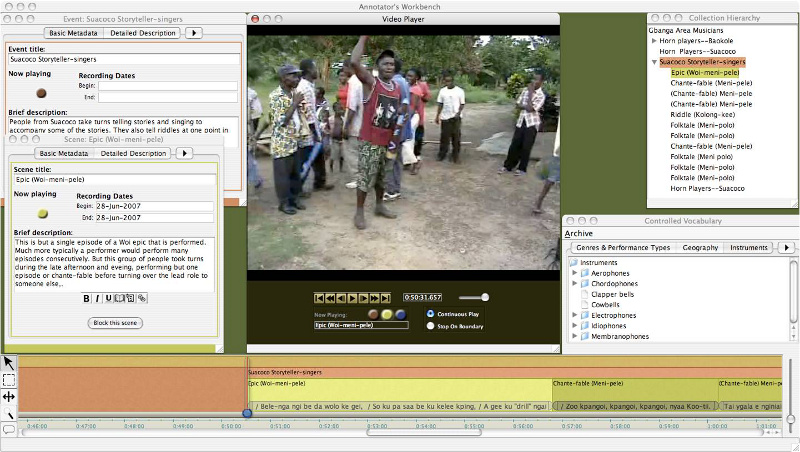

Today, I make recordings of music events on a solid-state digital recorder. I transcode those recordings to easily play them back on my computer. I’m able to flip open a laptop recorder in a village and share a recording with a small group of people (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Screen capture: Annotator’s Workbench.

More importantly, I can then co-create notes with my consultants in the Liberian village to accompany a video segment that will scroll with the video, using open source software developed for the EVIA digital archive project. The technology has made linkage of the different forms of research data much more possible. Interviews and notes can be tied to the recordings of performance in ways we could not even imagine when I was a graduate student. Beyond that, I can upload all of our digital data to a distant computer storage facility a continent or more away, protecting the data from all kinds of potential destructive possibilities. http://www.eviada.org/default.cfm (Accessed September 4, 2013)

Technology has empowered not only ethnomusicologists and transformed their work patterns. Technology has utterly changed the consultants in the far-flung places where they work. The cell phone is perhaps the most important tool on that account. Nearly every musician I work with in Liberia has access to a cell phone. This means that I hear from them regularly. We are in touch whether I am in Liberia or in the U.S. They let me know when family members die, when they have an important performance coming up, or that they are transmitting a translation to me that they have been working on with a computer I have left with them. Feme Neni-kole, a solo singer with whom I have worked more than 20 years, now lives in Utah and calls me most weekends to check in and update me on her life as a refugee. There’s little difference in the quality of phone transmission whether she is calling from Liberia or from the U.S. Distance has shrunk dramatically with the cell phone.

The Internet and the World Wide Web have also had a transformative effect on ethnomusicology. News of academic programs and professional organizations can be transmitted widely and instantly. The days of typing a newsletter and sending it through the mail are fading as electronic forms of publication co-exist for newsletters and journals. Furthermore, scholars can have daily conversations on Listservs and email.

Technology has enhanced both the speed and extent of the global flow of information. This technology has increased the scope of a field such as ethnomusicology where scholars can now access information more quickly and easily. Scholars are linking musical examples to texts in the electronic versions of their books and articles. Musicians who have been consultants have access to some of this information, depending upon their computer access. Students around the world can study texts and examples of performance with considerable facility. The gap between the original performance and the analysis has been narrowed considerably. Technology has provided tremendous tools even though the human interpreter is still critical, a point noted in a recent article on feedback interview (Stone-MacDonald and Stone 2013).

Factors in the Growth of Ethnomusicology

A number of other developments have contributed to the growth of ethnomusicology. These developments have had a role in the demand for ethnomusicology courses, which in turn has that led to the hiring of more ethnomusicologists, and to the growth of the professional organizations.

Music of the World and the Music Industry

Several decades ago, as recordings and the playback of recordings became accessible to people around the world, the music industry, which disseminates music that is often known as “popular” began inserting elements of music from different parts of the world into songs that became widely disseminated. Jazz musician Herbie Hancock drew from the music of Central African Republic for his hit tune “Watermelon Man” (1973). More recently Baba Maal in his Firin’ in Fouta (1994) album recorded sounds reminiscent of griots in Senegal. He made an original recording in a local village. Then he mixed it in Dakar and added Western popular music sound tracks. Finally, he took it to Paris for the final editing and layering of sounds. The final mélange drew from the music and sensibility of each place where he had worked with musicians and sound recording engineers. In the end, it became difficult to say just where the music originated.

These are but two examples of countless recordings of “world music” that layered sounds from around the world in popular music recordings of all kinds. Whether blues, reggae, or hip-hop were the basis of the music performance, they formed but one dimension of the final recording that freely mixed sounds and texts from the most remote places. Suddenly, a musician like James Brown or Bob Marley was in demand in a village in West Africa and the local musicians freely drew from what they heard.

And students in universities suddenly wanted to take classes to learn about what was being disseminated through the mass media. They longed to find out more about what they were hearing and what attracted them. Ethnomusicologists offered classes that related, even if somewhat tangentially, to what students were hearing on recordings and the radio. Mass media was marketing the music from the world as it fit into the popular music scene, and ethnomusicologists had little direct role in promoting this effect.

Music Tourism and Music Camps

As people began to learn about music of various parts of the world, they longed to travel to the places where the music was being made and learn more. Thus were born summer programs where people could travel, experience another culture, and learn to perform music on group of people. People flocked to Southeast Asia, to South Asia, and to Africa. And these opportunities have mushroomed up to the present time. In Ghana alone, there are at least three music camps that are run during the summer. Sometimes these are run by ethnomusicologists or master musicians who are connected to teaching programs in ethnomusicology during the academic year. Other times they are run by entrepreneurs with no linkage to academic ethnomusicology.

These music opportunities occur within the United States as well. Zimbabwean music is taught during Zimfest, which takes place in the Northwest each year, as well as at camps around the United States. The phenomenon is so widespread that Sheasby Matiure (2008) wrote his PhD dissertation based on ethnographic research he conducted in multiple sites where instruction in Zimbabwe music was taking place. As a scholar and a performer he possessed a unique perspective on the events and interchange between teachers and pupils.

These music schools and camps contributed to the involvement of American students in ethnomusicology. They fueled interest in academic study and frequently fostered a desire for academic study in ethnomusicology. The two weren’t equivalent but they overlapped in interesting ways—one fueled the other.

Diversity Issues

Several decades ago, initiatives to become inclusive and diverse in American higher education led to the creation of departments of African American, Latino, Native American, and other kinds of ethnic studies. A natural extension of teaching in these areas led to hiring of faculty to teach, among other things, courses in the music of these areas. At Indiana University, for example, three performing ensembles were created in the 1970s—Soul Review, African American Choral Ensemble, and the African American Dance Company. These all flourished within the African American Arts Institute and continue today to attract students who learn to perform in various African American traditions.http://www.indiana.edu/~aaai/index.shtml (Accessed September 11, 2013)

Similar patterns developed at other institutions. Ethnomusicologists helped to address the pressure for teaching diverse content for and about U.S. minority groups. Ethnomusicologists benefitted from these national trends and pressures. Schools often found course offerings in ethnomusicology to be a natural way to make instruction more diverse than had previously been the case.

Diaspora Pressures

The United States has a long history of immigrants settling in various areas and bringing their music and culture with them. During the last half century these immigrants have come increasingly from Mexico, Latin America, Southeast Asia, East Asia, and Africa. Some have fled oppressive regimes, wars, and conflicts. Others have come for economic opportunity. But all have become part of global patterns of population movement. And unlike the Irish or German immigrants of earlier years who simply came and stayed for the most part, some of these later immigrants have moved back and forth, living both in the United States and back in their home country as conditions become more favorable at certain moments.

I have worked over the last several years, for example, with a group of Liberian musicians in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They fled their homes during the recent civil war in Liberia, West Africa, and are now recreating their careers as musicians in the United States. The Philadelphia Folklore Project has assisted them in obtaining grants to teach music to children and to perform for eager audiences. Zaye Tete, for example, has made a recent album, Zaye Tete “Queen of Folk Songs” (2011), documenting the pain of leaving her home and living in a refugee camp in Cote d’Ivoire. Some of the songs on the album included titles like “For the Sake of the Children,” “Democracy, Where are You?” and “Cheaters.” She was one of several musicians who became the key instructors at a spring vacation camp where refugee youth could learn about Liberia music in a weeklong event to instill music and culture these children missed as they fled their home communities.

These recent immigrants to the African diaspora in the United States have opened up opportunities for ethnomusicologists, whether it is in public sector work or teaching opportunities at a range of levels from elementary to post-secondary levels.

Challenges Ahead

Ethnomusicology has enjoyed growth in academic course offerings, in professional organizations, and in new research areas, all fueled by technology and the global flows that have been enabled by computers and the Internet. Additionally, (1) world music and the music industry, (2) music tourism and music camps, (3) diversity issues, and (4) diaspora pressures have all played a role in the expansion of ethnomusicology. There are distinct challenges to this growth and expansion picture, however, that need to be considered to more fully understand where ethnomusicology may be moving in the future.

Institutionalization

While ethnomusicology has expanded and increased its scope, the degree to which it has been institutionalized within the academy, particularly within the United States, is still somewhat limited. More than fifty years after the founding of the Society for Ethnomusicology, there are very few departments known as Department of Ethnomusicology. One exists at UCLA, and Indiana has a Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology. There are also few degrees that are designated Bachelor of Arts in Ethnomusicology, Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology, or Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology though a few more schools offer the degree within a Department of Music, including University of Texas at Austin and Kent State University, among others. And Wesleyan University has a well-entrenched set of course offerings and world music performance venues.

Where ethnomusicology is not deeply and formally institutionalized, and ethnomusicologists retire, as a whole generation is presently in the process of doing, the chances are quite high that these specialist scholars will not be replaced with another ethnomusicologist. And the reasons are not just competing interest within departments. If ethnomusicology is not a firm part of the institution, then it is easier to simply eliminate the slot for an ethnomusicology.

Public education at university level, particularly, is being pressured by costs and contraction for a host of reasons that are well documented in the literature (Newfield 2003, 2008). As universities move increasingly toward corporate models, with research funding increasingly coming from the sciences and social sciences, the research university does not necessarily regard the arts and humanities as helping to fuel and build the university. More specifically, if a position for an ethnomusicologist is not critical to keeping a degree program with the name ethnomusicology attached to it, the chances of hiring another ethnomusicologist begin to diminish.

At liberal arts colleges, many ethnomusicologists have been hired into institutions where they are the only scholar of their kind within a department of music or related arts studies. They work in a universe where there may not be other ethnomusicologists to help provide pressure for their replacement when they move to another job or retire.

Definition of a Field of Study

Another challenge lies in the very definition of the field of ethnomusicology. Who is an ethnomusicologist? What does it take to become one? The Society for Ethnomusicology has not established well-articulated guidelines about what constitutes the appropriate training for an expert in this area. Furthermore, there is not a commonly accepted set of courses that most ethnomusicology programs teach for students studying for the various degrees in ethnomusicology.

Beyond that, is not uncommon to find musicians who perform some kind of world music to self-identify as an ethnomusicologist. The lines between performer and scholar become blurred. If one is a scholar, does one need specialized training to assume that title? This is an important question that the discipline needs to answer.

Conclusion

Thus, at the bend in the road today, while a number of the factors discussed earlier create a promising environment for ethnomusicology as a field of research and study, there are also challenges that pose considerable threat to the real establishment of ethnomusicology as a grounded and anchored field within the academy. As the field matures, there needs to be engaged discussion of what it takes to master the skills of an ethnomusicologist and those standards need to be broadly communicated. Leaving such definitions and requirements open-ended, as some in the field advocate, builds the impression that there is a lack of focus for the field. While there are some publications that provide biographies of ethnomusicologists, and one can study their patterns of training and activity as a scholar, these examples need distillation into more succinct definitions (Stone 2001; Nettl 2013).

Institutionalization of the ethnomusicology training and degree programs will also help create a much firmer foundation for the field and discipline than exists today. As an ethnomusicologist is then hired, she or he will likely be replaced with another ethnomusicologist. The Kpelle people of Liberia have a proverb that could be adapted to make the point. They say,

A ke ba taa too, wule too nuu fe zu, ge ni taa fe

A ke be taa too, feli-ygale-nuu fe zu, ge ni taa fe

If you build a town and there is no singer, then it is not a town,

If you build a town and there is no drummer, it is not a town.

To that I would now say, “If you build a university and there is no ethnomusicologist, then it is not a university.”

References

Barz, Gregory, and Judah M. Cohen, eds. 2011. The Culture of AIDS in Africa: Hope and Healing Through Music and the Arts. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hancock, Herbie, performer. 1973. Headhunters. New York: Columbia/Legacy. Audio Recording.

Maal, Baba, performer. 1994. Firin’ in Fouta. Bucharest, Romania: Mango Records. Audio Recording.

Matiure, Sheasby. 2008. “Performing Zimbabwean Music in North America: An Ethnography of Mbira and Marimba Performance Practice in the United States.” Ph. D. Dissertation, Indiana University.

Nettl, Bruno. 2013. Becoming an Ethnomusicologist: A Miscellany of Influences. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press.

Newfield, Christopher. 2004. Ivy and Industry: Business and the Making of the American University, 1880-1980 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

__________. 2011. Unmaking the Public University: The Forty Year Assault on the Middle Class. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Stone, Ruth M. 2001. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music Volume 10: General Perspectives and Reference Tools. New York: Routledge.

Stone-MacDonald, Angela, and Ruth M. Stone. 2013. “The Feedback Interview and Video Recording in African Research Settings.” Africa Today 59(4), 3-22.

Tete, Zaye. 2011. Zaye Tete “Queen of Folksongs.” Pennsauken, NJ: Disc Makers.