Collaborative Learning and the New Generation

In the 2013 TI:ME article “The Me Me Me Generation,” Joel Stein describes the characteristics of Millennials, students born between 1980-2000. While Stein focuses the beginning of the article on the negative attributes of Millennials such as narcissism, laziness, and the obsession with fame, other generalizations are presented including:

- Millennials are Social and Collaborative-they send on average 88 texts a day and 70% check their phone every hour. They are extremely loyal to their friends and are more inclined to work together on large projects

- Millennials are Interactive- they are most engaged in an interactive classroom, specifically in terms of technology and online applications

- Millennials are Thinkers-they tend to think through a situation, assignment, or life situation before actually beginning the task or committing

- Millennials desire new experiences-these “life experiences” are much more essential than a steady job or material goods1

Regarding Millenials’ view of technology and socialization, Scott Hess, senior vice president of human intelligence for Spark SMG stated in a Tedtalk:

“Millennials don’t have this problem (of isolation). They know where everybody is….They’ve checked in, I’ve got pictures and video. I don’t feel left out. Isoltation is being killed.”2

Perhaps this new population, along with the new paradigms and addiction to technology, are challenging to us as educators. Some faculty responses may even range from frustrating to inspiring. So, how do we embrace these changes in a manner to create a meaningful, productive, educational experience? How can we integrate these collaborative and interactive approaches along with new technologies into our curriculum?

In the book Collaborative Learning, author Kenneth Bruffee, states that “knowledge is a social construct, a consensus among the members of a community of knowledgeable peers.”3 The university culture has capitalized on this new focus on collaborative learning, creating programs such as learning communities and required study groups. Many music faculties have embraced the ideals of collaborative learning by integrating more discussions and group projects within the curriculum, and it is now common to see required group projects in the syllabi of music education, music theory, and music history courses. Several recent studies have been conducted regarding the use of collaboration and technology in the classroom (Salter et al, 2013; Tsai, 2013; Fisher et al, 2013). The Tsai study in particular noted that "The results reveal that students who received the combined treatment of online Collaborative Learning …with feedback attained the best grades for their computing skills for website design among the five groups."4 However, there has been little research conducted regarding the use of collaborative technologies within the traditional music theory classroom.

Research Questions

In order to capitalize on the characteristics of this new generation, faculty members at Appalachian State University and Washington College created two separate analysis assignments in the Spring of 2013 and the Spring of 2014. It was imperative that the assignments be collaborative and interactive, include the latest technologies, and enable students to create a new experience that broke the barriers set out by our brick and mortar classroom walls. The assignment had to serve a wide range of students from very different backgrounds with differing levels of analytical abilities. The ultimate goal and purpose of the project was to have a wide range of students find commonalities between themselves, identify analytical strengths and weaknesses, and take initiative to relate their thoughts to the rest of the group. All of this interaction was to happen solely through technological resources. The study sought to answer three main questions:

- How would students from two extremely different institutions, taught with two different theoretical approaches, begin a musical analysis?

- How would students embrace the social and technological applications involved in this project?

- How would students work through any disagreements in terms of analytical discoveries?

Institutions and Subjects Involved in Study

Founded in 1782, Washington College is a small liberal arts school on the Eastern shore of Maryland. The college’s student body consists of approximately 1450 undergraduates, with approximately twenty music majors. At the time of each study, all students, outlined in table 1, had studied chromatic harmony and basic formal elements and were beginning to study 20th-century techniques. The students are all taught using the method presented in Steve Laitz’s text The Complete Musician. Laitz’s approach is linear in nature and focuses on how chords function within the phrase model throughout the curriculum. Laitz also introduces formal elements early and covers form rather extensively in his text.

First founded as a teacher’s college, Appalachian State University is a large state university in Western North Carolina. The student body of Appalachian State is approximately 18,000, comprised of undergraduate and graduate students, with approximately 450 music majors. The students participating in the spring of 2013 had begun their studies of chromatic harmony, but had not studied form. All of the students who participated in 2014, with the exception of the music industry students, were taught using the approach presented in Tonal Harmony by Stefan Kostka and Dorthy Payne. Within this text, the approach to musical form is quite limited; therefore, the instructor opted to use materials created in house. The music industry students had been introduced to chromatic harmony, but had no understanding of classical musical form.

| Spring 2013 | Number of Students | Theory Level Enrolled |

|---|---|---|

| Washington College | 5 | Theory IV |

| Appalachian State | 8 | Theory II |

| Spring 2014 | ||

| Washington College | 8 | Theory IV |

| Appalachian State | 8 | Theory IV (6) and Theory for Music Industry (2) |

Table 1

Student Participants

Technologies Used in Study

The main purpose of the project was to better understand how students from two very different universities would approach an analysis of an assigned musical composition. A secondary research goal was to observe how students would embrace the social and technological applications involved in this project, specifically Skype and DyKnow. Extensive use has validated the use of Skype as an appropriate and efficient tool in the classroom5 While most educators are very familiar with Skype, DyKnow Vision is a newer technological tool for the classroom. According to the developers, Dyknow enables students to trade files, submit analyses, and work collaboratively and simultaneously on a single uploaded image in real time.

Several studies have been published that document the efficacy of DyKnow as a collaborative tool. The study by James et al (2006) indicated that “In general psychology, 87 percent of the students in the pilot [DyKnow] section earned a C grade or better compared with 73 percent in the control sections; 13.3 percent of the students in the pilot [DyKnow] section withdrew compared with 23.7 percent in the control sections.”6 Another study by Roy and Luthara (2008) involved twenty students enrolled in the American School of Bombay (India) who were asked to use DyKnow for all note-taking and real time panel submission. The results of this study indicated that “70% agreed that using DyKnow enhanced their understanding of course material as it was presented during class; 70% of students also agreed that when they use DyKnow in class they are able to get more feedback about how they are progressing with class material; 55% said that using DyKnow in class allowed them to learn more from their peers than in a traditional lesson.”7 The DyKnow software has been frequently used for collaborative work within the classroom; however, few have used the software for long-distance collaborative work in real time.

Spring 2013 Study

A total of thirteen students agreed to participate in this study. The students from Appalachian State were grouped 2+3+3, with the Washington College students grouped 2+2+1, respectively. As a result, Group 1 contained 4 students, Group 2 contained 5 students, and Group 3 contained 4 students. The selection of these groups was not random; they were grouped based on skill level and work ethic.

As shown in the assignment sheet presented at the conclusion of this article, all students were asked to individually complete both a formal and harmonic analysis of Schubert’s Die Liebe hat gelogen, D. 751 before meeting with the analysis group in order to compare analytical interpretations. Once each group had their analysis completed, they would be prepared to collaborate with their partner institution group via DyKnow and Skype.

The groups were asked to schedule a two-hour block to meet via DyKnow and Skype. The professors would initiate the DyKnow session, but not interfere with any of the analysis and were not physically present during the session. The students used Skype to talk through the analysis, while working through the score in real time via DyKnow. The professors saved each DyKnow session in order for the offline viewing and assessment at a later time. Upon completion of the analysis, each group was asked to write a short paper outlining their analytical findings, discrepancies, and conclusions. This paper was required to be the same for all group members and was to be completed in a similar collaborative manner using GoogleDocs.

In addition to the analysis, each individual student was asked to provide a personal response to the project. Within these statements, students were asked to address any analytical disagreements and to discuss how these disagreements were overcome (if they were at all). They were asked to describe how working in a collaborative environment impacted their analytical discoveries, if at all. Finally, they were to state any issues they may have had working at a distance with students from different backgrounds. The entire project was graded upon both completion of the project and accuracy of the analysis. Both professors graded all of the projects (interestingly enough collaboratively via text and phone) and read all of the personal responses from both institutions. Students from AppState received extra credit for participating in this project, while Washington College students were required to participate as part of their course grade.

Student Process

Each group began this project in a similar fashion. Upon completion of their analyses, groups worked to schedule a time in which everyone could meet. This proved rather complicated for some groups, as their schedules did not allow many windows in which to work.

Group 1 had the easiest time with scheduling and was the first group to meet. This group was comprised of four students (two from each school). The students all brought different interpretations to the group discussion, which was quickly revealed upon completing the analysis together. While it took several attempts for Group 2 to find a suitable meeting time, the four students were able to connect and discuss the analysis; however, the students from Appalachian were underprepared when the live session began. Group 3 was unable to meet due to the lack of response from a student from Washington College. The Appalachian group met together, but were unable to utilize any of the collaborative analysis tools with the exception of GoogleDocs.

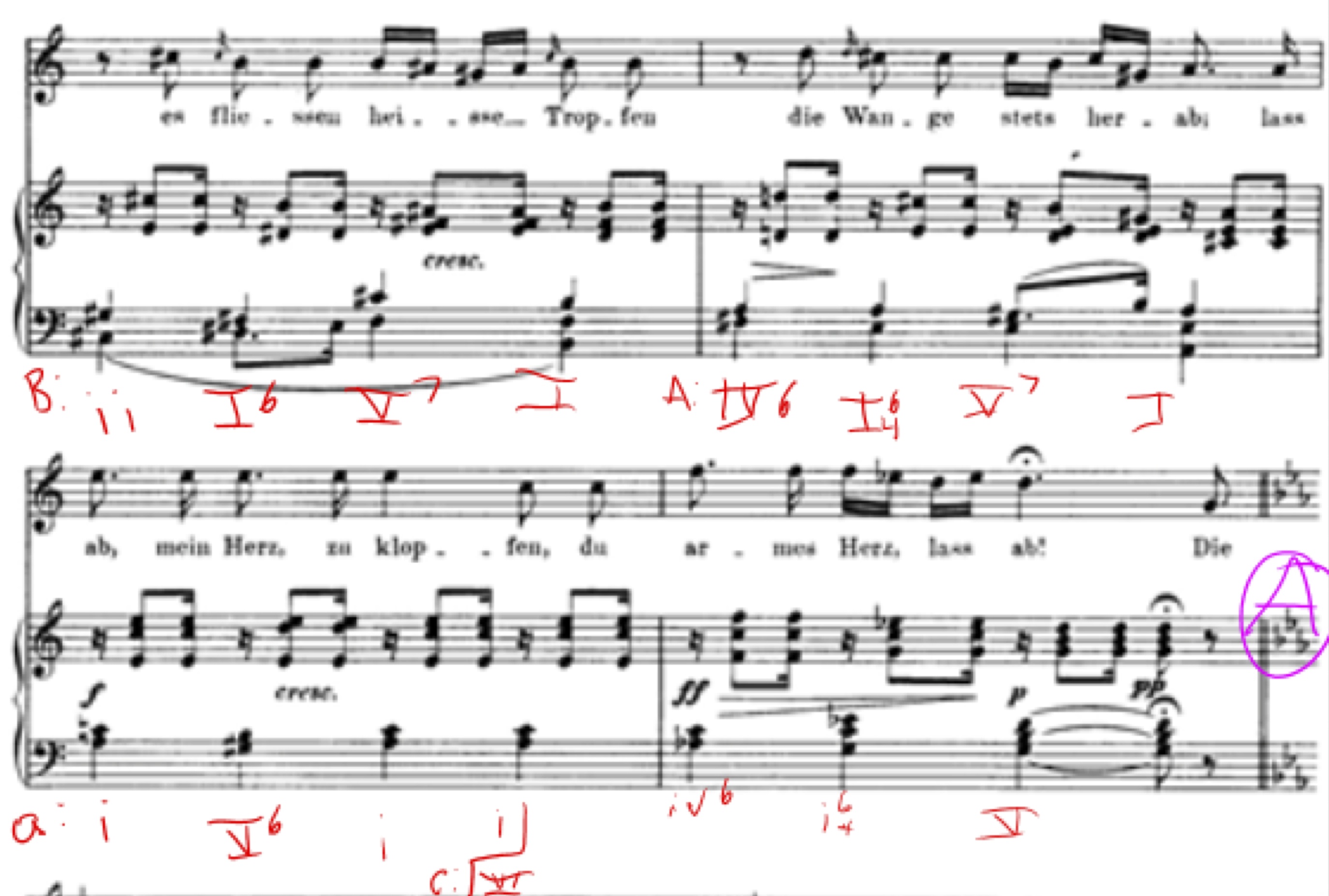

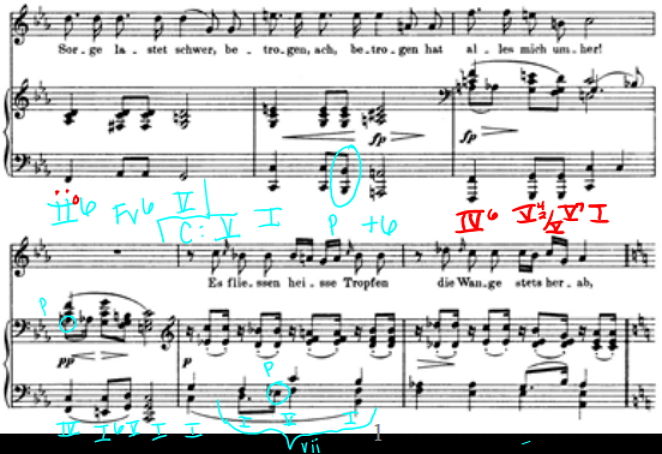

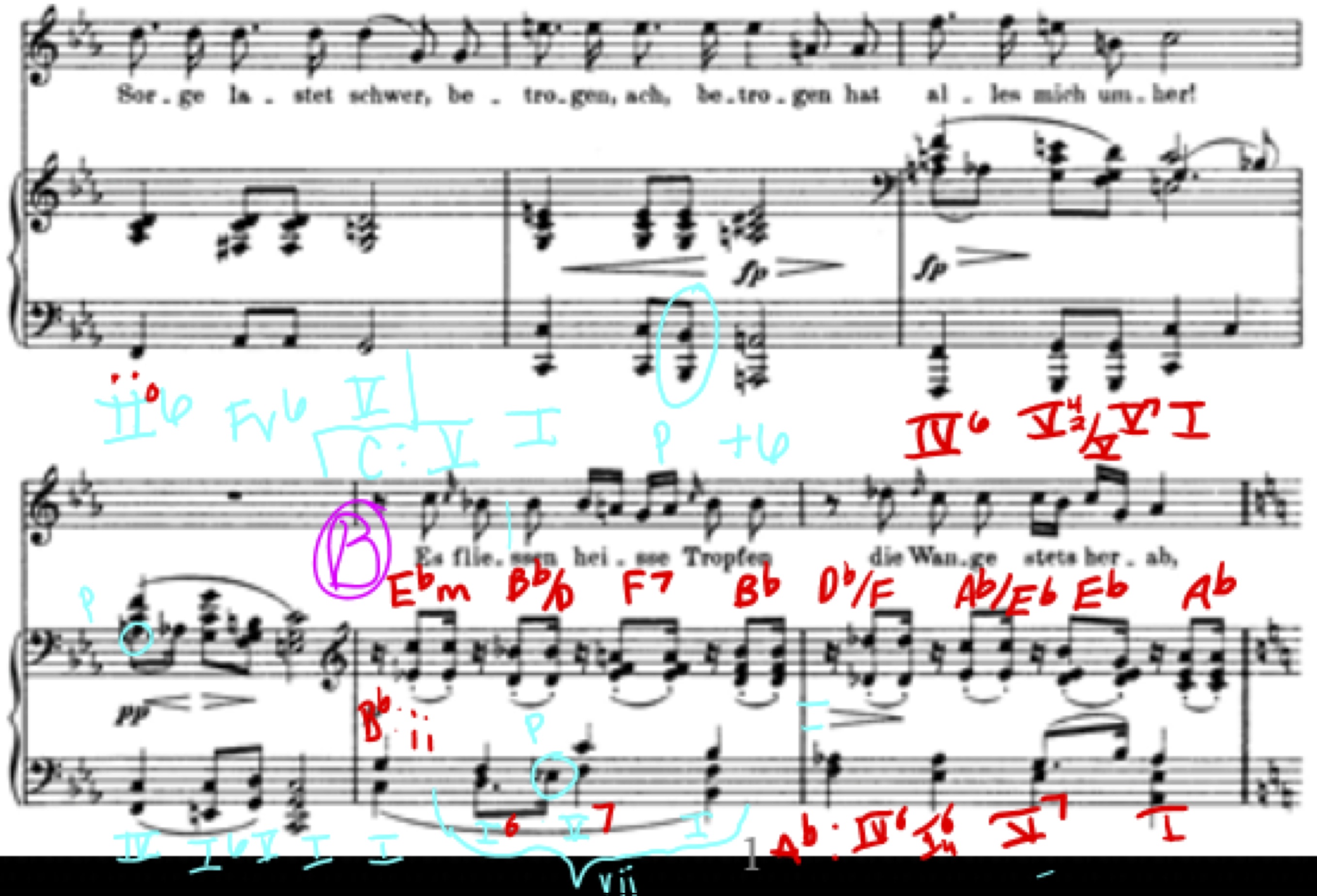

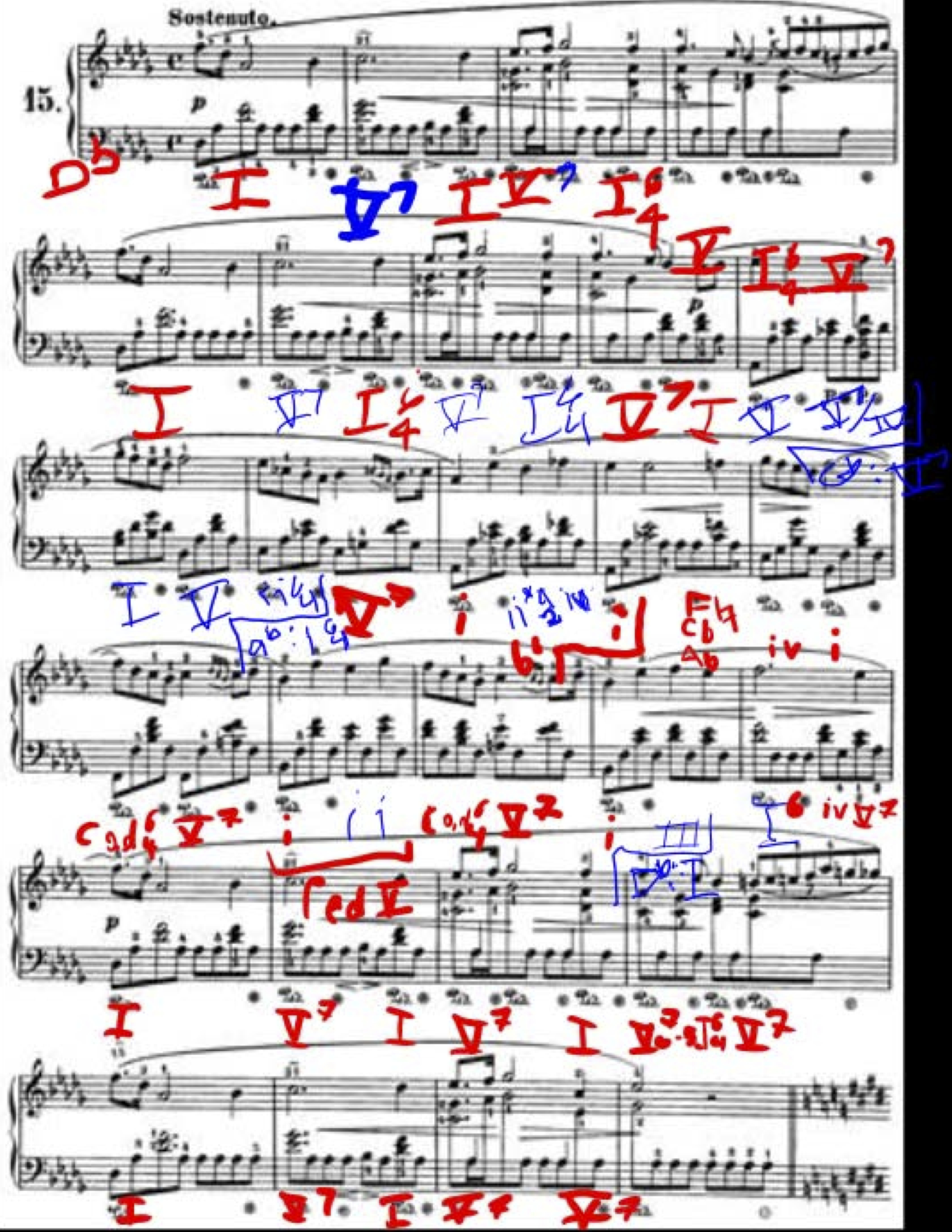

The first discussions came from Group 1 as they worked to determine whether the composition contained modulations or tonicizations in measures 8-12. Shown below in Figure 1 and Figure 2, The Washington students had labeled these as tonicizations, while the Appalachian group called these direct modulations.

Figure 1: Direct Modulations in measures 10-13

The students were all engaged in a well-articulated discussion about their justification for the both the tonicizations and modulations. The Washington students used this discussion to teach the Appalachian students about how larger-scale tonicizations function and how to label them. Ultimately, the Appalachian students were able to sway the opinion of the Washington students and everyone came to the agreement that these measures included modulations.

Figure 2: Initial analysis of measures 8-9

Blue markings are Washington College; Red markings are Appalachian State

Figure 3: Final analysis of measures 8-9

The students from Appalachian seemed to have a better facility in labeling the individual chords. There were a few instances throughout the score where the students from Washington College struggled to find the correct Roman numeral, quality, and/or inversion (see Figures 2 and 3). The students from Appalachian were able to coach them through the analysis and achieve the correct label. While there were still several mistakes within the analysis, the Appalachian students were able to articulate their analytical process in a manner understandable by the Washington students.

Given their strong linear background and knowledge of form, the Washington students were generally more concerned with larger-scale implications, while the Appalachian students were focused more on localized events. This was clearly seen as the Washington students brought a translation of the lyrics into the analytical discussion. The Appalachian students had not given any thought to the lyrics and how they might impact the analysis of the music. The Washington group explained the meaning of the text and how it aligned with their analysis, igniting more excitement among the Appalachian group. This created a more energized discussion and, ultimately, a more informed analysis.

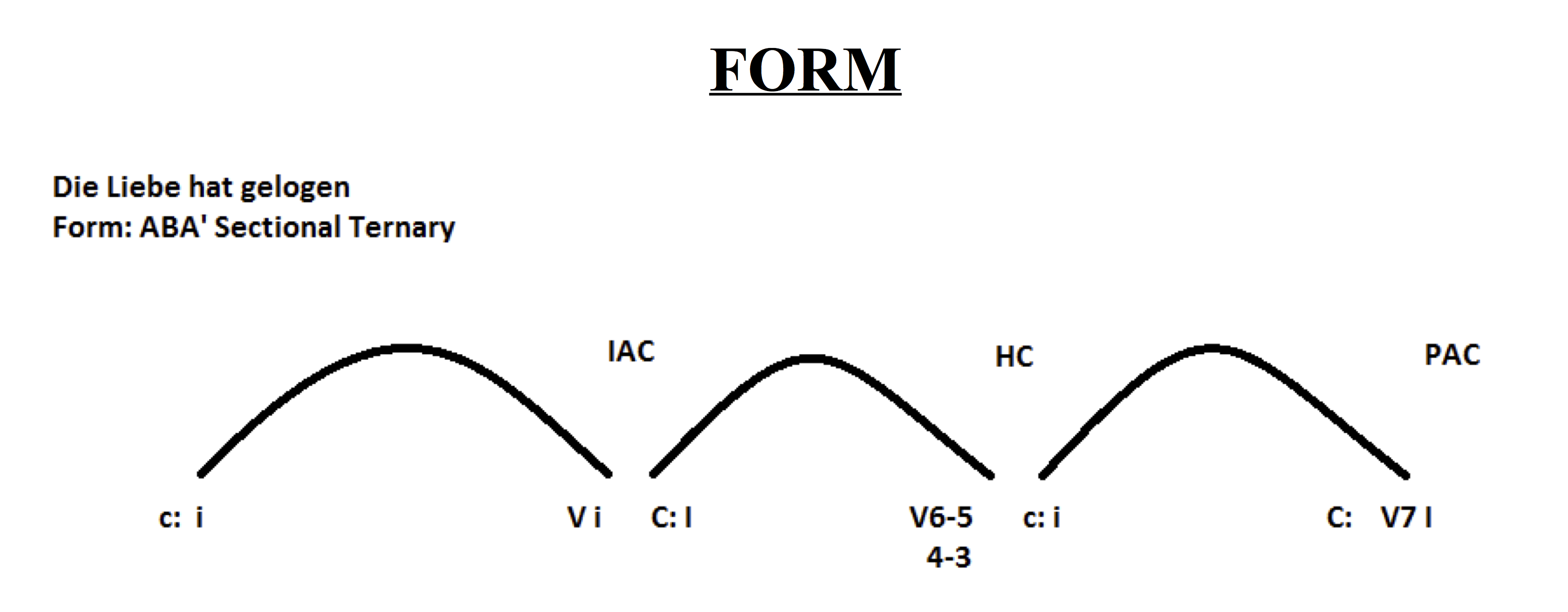

Prior to this project, the Appalachian students had little exposure to form. This was another area where the Washington students were able to become teachers. They explained their thoughts on the form of the piece and how to label both the large scale forms and smaller formal elements. The Appalachian students were very receptive to learn about the form and the entire group made the decision to include this discussion in the final group paper based on a simple form chart, shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Formal diagram produced by group 1 at Washington College

Results of 2013 Study

The results of this study indicate that students were interested to learn from each other, specifically in the varying perspectives in terms of analysis. Most of the students involved were excited about this project and enjoyed the opportunity to meet music majors from another institution, one student from Appalachian responding, “frustration was never an issue during our meeting because we all were so fascinated by what the others had to say.” Another student responded, “working together with a couple other students was such an awesome experience. It definitely challenged the way I look at and interpret music, and it was awesome to see what steps they take to debunk certain chords that look crazy in certain keys.”

Several students did indicate frustration of working with students that were not prepared for the assignment, one student saying “it was like corralling preschoolers” Another student responded, “the Skype session took longer than it should have because the group members were lackadaisical about the analysis, which made it seem like they were hoping that we had all the answers for them. ” While not stated in response papers, we heard verbal feedback of some slight issues created by the AppState students receiving extra credit while the Washington College students projects were part of their course grades. Some Washington College students felt this caused the AppState students to take the project less seriously.

In terms of analysis, we both noticed a distinct difference in the labeling of cadential six-four chords as well as the subtle differences between a tonicization and modulation. The process of which the students approached chromatic harmonies also provided great insight. The Appalachian students would work backwards from the end of the phrase and rely on lead sheet symbols, while the Washington students would often talk about stacking the chords in thirds and determining the quality, resulting in “some funky Roman numerals” (student quote).

Spring 2014 Study

A total of sixteen students agreed to participate in the second round of this study. The students were arranged together in groups of four, with two students in each group from both institutions. Again, the selection of these groups was not random; they were grouped based on skill level and work ethic.

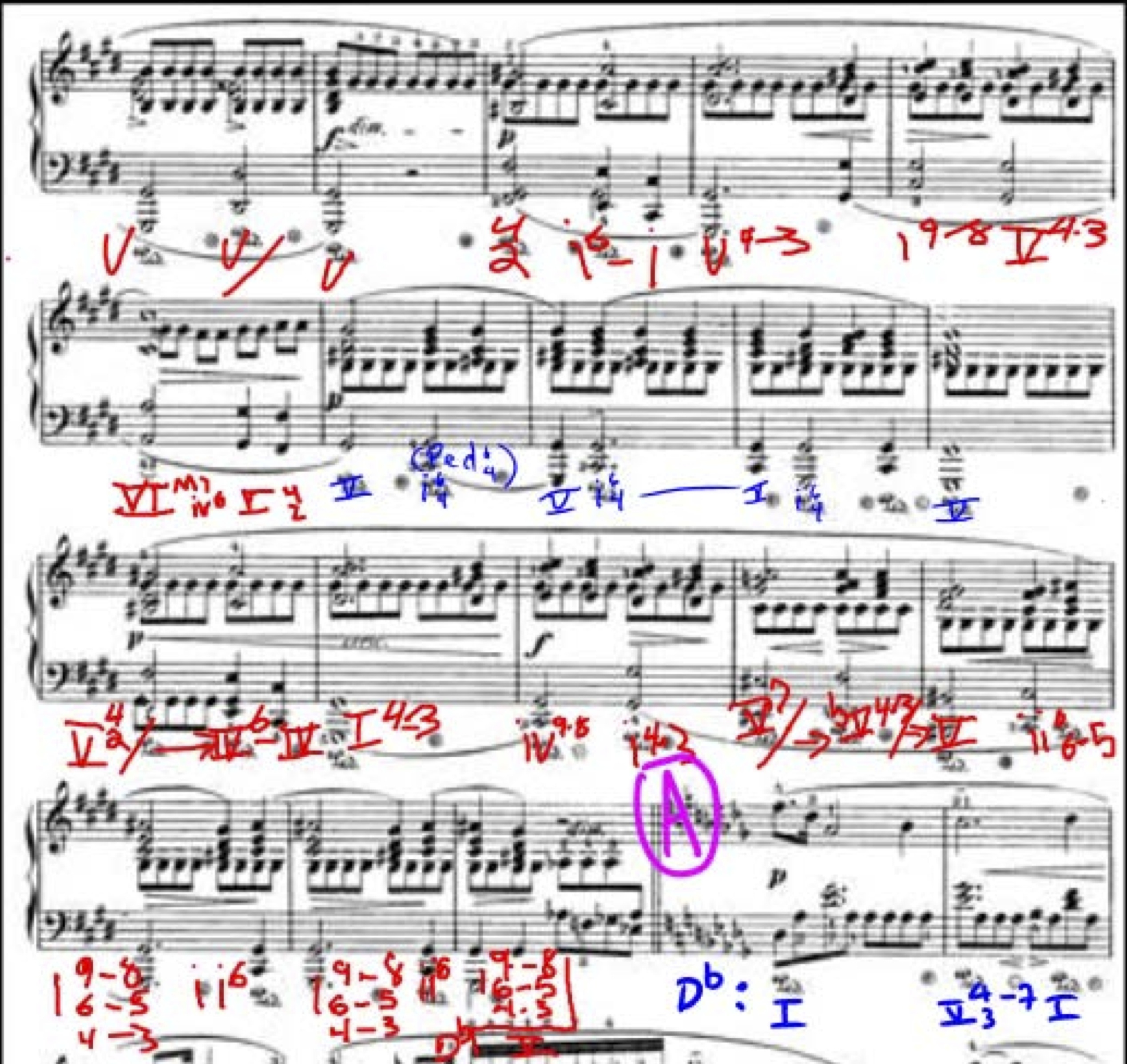

As shown in the assignment sheet presented at the conclusion of this article, all students were asked to individually complete both a formal and harmonic analysis of Chopin’s Prelude in D-flat Major before meeting with the analysis group in order to compare analytical interpretations. Once each group completed their analysis, they would be prepared to collaborate with their partner institution group via DyKnow and Skype. The process was identical to the initial 2013 study and students were asked to find a time to meet together to discuss their analytical findings while marking the score provided in DyKnow.

Unlike the 2013 study, all of the groups met and participated in the study, even though many of the groups commented on their difficulty in finding a mutual time to meet in real time. This particular analysis was more straightforward when compared to the Schubert composition used in the 2013 study. Because of this, more focus was placed on points of modulations and how these affected the overall musical form.

Results of 2014 Study

In the summary statements provided by the students, it was evident that this assignment was an interactive learning experience and students described the experience as both “enlightening and frustrating.” One student from Appalachian noted, “In our analysis of this piece, having multiple different perspectives working on the same piece helped us achieve a larger view of the piece. With four different people working on the project and four different views of the piece, we were able to pool our ideas and work together, have a discussion, and choose parts of our work and create a more complete analysis than one of us could do alone.” Another music education student noted, “When I would get to caught up trying to force my analysis to fit the music, my group members would help me discover that I really needed to listen closer at certain parts to find out what key or context I was actually trying to put Roman numerals to. As for working the most with a person with a different background in theory than me, I didn’t find it frustrating so much as a pleasant opportunity. One of the best ways to see if you know something is to try to teach someone else.” A music industry student shared his thoughts on the assignment saying, “It did make it frustrating when they would talk about things that I didn't understand, but I was able to keep up and they would explain it to me if I had questions. My input to the group let them step back if they were over thinking a section and I helped them come up with the simple solution.” Another student commented, “working on this project opened up a new perspective on music theory analysis that I had never considered before: it can be collaborative and social. We were able to appreciate and understand the music we were analyzing in a much more in depth manner because we were forced to critically think and explain our reasoning for our analysis.”

Similar to the study in 2013, several students expressed frustration, one Appalachian student writing, “I became frustrated several times and would end up saying we agreed, when we honestly didn’t, simply because it was too much trouble to try to explain what we meant. It was also frustrating because we felt like they had not put in enough time and/or thought into the analysis prior to our meeting.” One primary complaint of students centered around scheduling. A Washington College student said, “choosing a good time to work with my group at Appalachian State was likely the largest obstacle because we all had various finals, practices, and other commitments to attend to.” Other students stated having difficulties with technology, such as Skype periodically not working properly on Washington College’s wireless network. Another student noted, “We had a lot of last minute decisions made about a meeting time. I do not have email on my phone, so sometimes I would not get these emails until it was too late. I felt very left out by this and like I was not able to contribute as much as I could have to the group.” This same student continued by addressing frustrations encountered due to time constraints: “I still don’t feel like I totally understand everything because of the difficulty communicating and the need to rush through everything to get it done rather than being able to completely discuss the unclear parts.”

In terms of analysis several different approaches were made apparent as the initial slides were reviewed, including the labeling of cadential six-four chords and points of modulations.

Group 2 highlighted several of their analytical disagreements in the final analysis paper including a discrepancy in the point of modulation,

A disagreement our group had was on determining how many times the A section modulates. At first some group members thought it stayed in the key of Db until it modulated to Bb minor rather than modulating to Gb major beforehand. To solve this problem we first tried relistening to the section in question. After a second examination, we all came to the consensus that it did modulate to Gb major. The fact the harmonic analysis made more sense contextually in the key of Gb was also a strong factor in accepting this conclusion.

Also worth note, Group 2 was the only group who did not use different color pens to denote school for their analysis on DyKnow.

Figure 5: Group 2 analysis of first page modulations

Group 3 also experienced several disagreements; however, they were never really resolved. In their analysis paper, they indicated that,

…the only differences in approaches to analyzing the piece were very small, such as the placement of the new key name in a modulation. These differences did not affect the overall analysis of the piece, and any discrepancies in our analyses were typically due to small mistakes or notes not taken into account.” Both professors quickly sent the following feedback, “a point of modulation isn’t a small difference..it really could impact how everything works in a passage.

Figure 6: Group 3 analysis of first page modulations

Group 4 also indicated a few areas of disagreement in terms of tonicizations, especially in the B section where they questioned the fortissimo E major chord:

(We) had some dissenting opinions on the section around the fortissimo E major chord. Should we call it a modulation to E major, or is it only the major III chord in C-sharp minor? Both groups agreed that it sounded like the III chord, but some members thought the B major chord should be analyzed as a secondary dominant of the III chord, thus tonicizing that tonal area briefly. Others thought it was simply the flat subtonic chord, VII, in C# minor. Both analyses make sense, but finally we agreed that the III chord is tonicized briefly. Therefore, we analyzed the B Major chord as a V/III.

Figure 7: Beginning of B section analysis by Group 4

This group continued in a healthy discussion of key areas at the conclusion of the B section:

The second area that both groups had some differing harmonic analyses was in the last 3 ½ lines I “B” section. At measure 64, both groups agreed that either the rest of the “B” section could have either stayed in the original key of C-sharp minor, or modulate to its minor V chord which is G-sharp major. We agreed with its change into G-sharp major because of the consistent use of A#s, a tone diatonic in the key of G-sharp. This new key stays until the last chord of this section in which in the key of G-sharp, the final chord ends with a minor I chord with multiple suspensions, and in the pivot into the original key of D-flat Major ends up being the V chord.

Figure 8: Conclusion of B section analysis by Group 4

Conclusions

In conclusion, we both feel strongly that this is a valuable project worthy of replicating. As strong advocates of pedagogy, we both were excited to see our students alternate between the teacher and student role. With a few exceptions, the students all indicated that they enjoyed the experience and were able to have a deeper understanding of the composition because of the collaborative nature of this project. Perhaps one Appalachian student said it best in her final reflection of the experience: “I got so much out of the entire experience, and I feel that my approach and attitude toward theory after this collaboration is so much more positive than before”

It is our hope that we continue to engage these Millennials in a meaningful, productive, and pedagogically sound experience. Perhaps through the inclusion of more projects like this into the core theory curriculum, students will have the opportunity to become more confident in sharing their analytical interpretations, no matter the distance between the scholars.

A video outlining the process and results of this project may be viewed on YouTube

Assignment 2013

Group Analysis Project: Schubert, Die Liebe Hat Gelogen

Appalachian State University and Washington College

IN CONJUNCTION WITH STUDENTS FROM THE OTHER SCHOOL, discuss the results of your analysis via Skype, googledocs, and DyKnow.

Each group’s final document should be emailed to both instructors no later than 12:00 pm on Friday, May 3.

Assignment

- Choose a 2 hour time slot where you and your group will meet together in a DyKnow session. Please send these times to Drs. Leupold and Snodgrass as soon as possible.

- Before your group meeting, complete a harmonic analysis of the entire piece. Pay careful attention to the modulations and chromatic chords!

- Meet together with your group to mark up score using DyKnow. Your analysis should include Roman numerals and labeling of important non-chord tones. Other markings could include phrase charts, formal sections, etc..

- Using googledocs, compose a 2 page paper outlining your overall analysis. Be sure to describe Schubert’s use of chromaticism and modulations. This document will be the same for all members of the group.

- In a separate file, document any instances of disagreement in terms of analytical interpretations or approaches. How were these conflicts resolved, if they were in fact resolved in your group setting?

- In this same file, include a summary statement on how working together on a collaborative assignment impacted your analytical discoveries. Were you able to see things in a new way, or were you frustrated by having to work with someone from a different background?

- These responses should be completed on an individual basis (DO NOT use the same responses for the entire group).

- Email the final documents to both Dr. Leupold (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) and Dr. Snodgrass (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.)

Your grade will be based on both completion and accuracy and evaluated by both instructors.

Assignment 2014

Group Analysis Project: Chopin, Prelude in D-flat Major “Raindrop”

Appalachian State University and Washington College

IN CONJUNCTION WITH STUDENTS FROM THE OTHER SCHOOL, discuss the results of your analysis via Skype, googledocs, and DyKnow.

Each group’s final document should be emailed to your instructor no later than 12:00 pm on Friday, May 7.

Assignment

- Choose a 2 hour time slot where you and your group will meet together in a DyKnow session. Please send these times to Drs. Leupold and Snodgrass as soon as possible.

- Before your group meeting, complete a harmonic analysis of the entire piece. Pay careful attention to any modulations, modal shifts, and/or chromatic chords!

- Meet together with your group to mark up score using DyKnow. Your analysis should include Roman numerals and labeling of important non-chord tones. Other markings could include phrase charts, formal sections, etc..

- Using googledocs, compose a 2 page paper outlining your overall analysis. Be sure to describe Chopin’s use of chormaticism and overall form.

- Document any instances of disagreement in terms of analytical interpretations or approaches. How were these conflicts resolved, if they were in fact resolved in your group setting?

- Create a summary statement on how working together on a collaborative assignment impacted your analytical discoveries. Were you able to see things in a new way, or were you frustrated by having to work with someone from a different background?

- Email the final document to both Dr. Leupold (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) and Dr. Snodgrass (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.)

Your grade will based on both completion and accuracy and evaluated by both instructors.

Bibliography

Bruffee, Kenneth A. Collaborative Learning: Higher Education, Interdependence, and the Authority of Knowledge. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Caruso, Charlie. Understanding Y. Hoboken: Wiley, 2014.

Courts, Bari, and Jan Tucker. "Using Technology To Create A Dynamic Classroom Experience." Journal of College Teaching and Learning 9 (2012): 121.

Fisher, B., T. Lucas, and A. Galstyan. "The Role of iPads in Constructing Collaborative Learning Spaces." Technology, Knowledge and Learning (2013): 165-178.

Hess, Scott. "Millenials: Who They Are & Why We Hate Them." YouTube Video, 21:32. Posted by "TEDx Talks," June 10, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P-enHH-r_FM.

James, T., J. Hill, C. Cone, and S. Latimer. "The Calf-Path: One University's Experience with Pen-Enabled Technologies." The Impact of Tablet PCs and Pen-Based Technology on Education (2006): 95-102.

Roy, Jason and Shabbi Luthra. "Implementing Dyknow for Secondary Mathematics Instruction." The Impact of Tablet PCs and Pen-Based Technology on Education (2008): 129-136.

Salter D., D.L. Thomson, Lam, J., and B. Fox. "Use and Evaluation of a Technology-Rich Experimental Collaborative Classroom." Higher Education Research & Development (2013): 805-819.

Stein, Joel. "The Me Me Me Generation." Time. (May 20, 2013): 26-34.

Tsai, Chia-Wen. "An Effective Online Teaching Method: The Combination of Collaborative Learning with Initiation and Self-Regulation Learning with Feedback." Behaviour & Information Technology (2013): 712-723.

Notes

1.Stein, "The Me Me Me Generation,” pg. 32-34.

2. Hess, "Millenials: Who They Are & Why We Hate Them." (13:00-13:12).

3. Bruffee, Collaborative Learning, pg. 3.

4.Tsai, “An Effective Online Teaching Method,” pg. 712.

5.5 Courts and Tucker, “Using Technology To Create A Dynamic Classroom Experience.”

6. James, Cone, and Latimer, "The Calf-Path: One University's Experience with Pen-Enabled Technologies," pg. 100.

7.Roy and Luthara, “Implementing Dyknow for Secondary Mathematics” Instruction," pg. 135.