Introduction

The course, Music and World Events Since 1945, is a graduate multidisciplinary seminar centering on works by major composers in direct response to world events such as war, disease, protest, human rights movements, and environmental issues. Designed and first offered at Roosevelt University in 2013, the course integrates world history, music history, and music theory. The present article will describe the goals, structure, content, and outcomes of this seminar and will document the use of media support for instruction.

Artist as Citizen

Music and World Events was inspired by Roosevelt University’s mission statement, which calls for “socially conscious citizens who are leaders in their professions and their communities.”1 To this end, my primary goals were to increase the students’ awareness of current events and empower them to actively engage their communities as artist-citizens.

The artist-citizen model is not new but has gained considerable momentum in American schools of music in the past decade. Books such as The Artist as Citizen2 and Beyond Talent3 seek to liberate young musicians from a traditional conservatory-style education and prepare them for new projects and modes of working with alternative audiences and venues. Here in Chicago, where Roosevelt University is situated, many high-quality musicians and ensembles focus on outreach, access, education, and civic engagement. Roosevelt alumna Allegra Montanari, a cellist, created Sharing Notes, a service group that organizes performances in area hospitals.4 The Civic Orchestra of Chicago, a training branch of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, launched a Citizen Musician fellowship program for young professionals under the leadership of Yo-Yo Ma.5 The Merit School of Music’s Tuition-free Conservatory connects professional musicians to motivated young students from every slice of the socio-economic spectrum.6 The Fifth House Ensemble, an up-and-coming chamber group, devotes much energy to outreach through its OneShot! educational concert series.7

This appeal to civic-mindedness surges as many in the industry doubt the viability of traditional music making, both as a financial and a social activity. In 2013, the College Music Society convened the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major (TFUMM) in response to “challenges” to collegiate music training, “particularly in the classical music realm.”8 Citing rapid technological progress and the concomitant interconnectedness of today’s global society, TFUMM recommended sweeping curricular reforms in a November 2014 report. The reforms stressed diversity and integration: “students must experience, through study and direct participation, music of diverse cultures, generations, and social contexts…the primary locus for cultivation of a genuine, cross-cultural musical and social awareness is the infusion of diverse influences in the creative artistic voice.”9

Part of the challenge, according to TFUMM, is that efforts to cultivate social awareness are not currently central to the music curriculum, but are either peripheral or entirely absent. In many cases, “social awareness” is relegated to elective courses or workshops in career building or entrepreneurship. While entrepreneurial training is certainly important for students who wish to generate their own opportunities beyond traditional avenues in the music industry, I wanted to design a course that would marry the emphasis on social engagement with more mainstream curricular areas such as music theory and music history. In doing so, students would not only have an opportunity to reinforce prior learning in theory and history, but could also apply this information to their own entrepreneurial activities and career plans.

I also attempted to dispel a common misconception among modern musicians: that social awareness and entrepreneurship are new ideas. Some commentators assert that social engagement is a hot trend, the mark of a “21st-century” musician. They feel that traditional performing arts organizations (professional orchestras and opera companies) are inherently conservative, passé, “slow to change,” and unable to “deal with new problems and react to new social phenomena.”10 This view maintains that modern musicians should function differently from the masters of the past, whose music stagnates in the stuffy air of the concert hall, and who labored in isolation to fashion music for the privileged few.

While this viewpoint may contain slivers of truth, the overall picture is quite the opposite. Social engagement is not new. Major composers from every style period of the Western canon—Monteverdi, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Ravel, and many more—interacted deeply with the world around them and desperately sought to share their music with a wide audience. Mozart, for example, was an entrepreneur par excellence whose operas are drenched in crisp social commentary.11 Today’s young professionals should rather strive to imitate the masters of the past and learn from their efforts. TFUMM recommends Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, and other masters as models for today’s “improvisers-composers-performers.”12 Naturally, we cannot expect modern musicians to function exactly like Mozart or Bach, but we can apply principles from their lives and work to the current age. In Music and World Events, I wanted to show my students that the artistic impulses of diversity, integration, awareness, and community have been present the entire time, waiting to be discovered in the masterpieces of the recent and distant past. We simply need to study them.

Student Work and Assessment

As a gateway to this study, in our first class session I distributed a “Communication Survey” to the students. This document was merely a list of tasks and questions to consider for each composition to be examined in the class:

1. Describe the event and historical context behind the musical work.

2. In what way was the composer connected to this event?

3. What was the composer’s goal in creating the work?

4. Who was the intended audience?

5. Describe the materials, methods, and techniques used in the work.

Assignments for Music and World Events included readings, score study, critical responses, online discussions, and a comprehensive final project. I selected a world history textbook13 to provide background for required readings from relevant musical scholarship. For each reading, students completed and submitted a critical response assignment with four necessary components:

1. A citation of the reading in Chicago Manual of Style format.

2. Thesis and main points of the reading.

3. Discussion questions. (I would regularly jumpstart a session by selecting a student to pose their discussion questions to the entire class.)

4. Opinions or reactions to the reading.

The final project unfolded throughout the semester in several stages. The students were asked to select a recent or ongoing world event of impact. They then completed a formal research paper on the event, followed by a creative response in the artistic medium of their choice. My goals here were immediacy and empowerment: for the students to discover the world around them, as well as their ability as artists to engage powerfully with it. Research topics covered wide ground, including the Israel-Palestine conflict, the Tuscaloosa-Birmingham (Alabama) tornado of April 2011, the Darfur genocide, the Mars rover Curiosity, and the Basque separatist group ETA. Creative responses took on a variety of media such as slideshows, acoustic and fixed-media compositions, paintings, sung poetry, and prose. In the closing weeks of the semester, each student presented his or her research paper to the class and performed or presented the creative response. The overall project schedule proceeded as follows:

Project proposal, due in Week 2.

Research bibliography in Chicago style, due end of Week 3.

Research paper (rough draft), due in Week 7.

Research paper (final draft), due in Week 10.

Creative response due on the date of the final presentation, Weeks 12-14.

Course Content: Six Contexts

Lesson plan content addressed the music at hand in the following six contexts: world history, composer biography, reception history, theoretical analysis and technique, style, and aesthetics. Due to time limitations, not every piece of music on the syllabus could be thoroughly examined in all six contexts. Over the course of the semester, however, I made sure that each context would be highlighted at least once. The following case studies, chosen from the syllabus, demonstrate how each context was featured. For each musical example below, I will provide context from scholarly sources used in class, thereby making a case for each work’s inclusion in the course. Then I will describe the students’ reactions to the piece in the form of opinions, questions, and arguments; I temper these with my own observations and critical queries.

World History

The natural starting point for Music and World Events Since 1945 was World War II. After reading from the Palmer textbook,14 students encountered works by Britten (War Requiem), Shostakovich (Symphony no. 7, Leningrad), Prokofiev (Symphony no. 5), Poulenc (Figure Humaine), Schoenberg (Survivor from Warsaw), Penderecki (Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima), and Reich (Different Trains). I omitted other important works (such as Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps) due to insufficient time. Granted, a few of these works were composed before 1945, but most of them were written in 1945 or after the conclusion of the war. I also assigned biographical readings on each composer.

This unit on World War II consumed a third of the semester, but through this prolonged study I wanted to make a larger point: that one massive event in world history could dramatically impact the lives of nearly every major composer of a generation. Moreover, each composer was impacted differently—even composers residing in the same nation. While Shostakovich endured the Nazi siege of Leningrad and served as a fireman,15 Prokofiev was shepherded out of Moscow and kept safe at various Soviet retreats far from the front lines.16 For Prokofiev, the war years were artistically restorative and fruitful. Poulenc’s daily life and material possessions were affected very little by the war; only late in the conflict was he moved to compose Figure Humaine on poetry by Paul Éluard, who was heavily involved in the Résistance.17 Schoenberg and his family had experienced anti-Semitism from the early 1920s; he was suddenly notified in 1933 that his employer, Berlin’s Academy of the Arts, no longer welcomed “Jewish elements,” and he emigrated to the United States some months later.18 Schoenberg learned from letters that several family members, friends, and former students narrowly escaped the Nazis, while others, including his niece Inge Blumauer, were tragically murdered.19 Reich did not experience the war firsthand, but reflected on train trips he took as a young boy from New York to Los Angeles: “If I had been in Europe during this period, as a Jew I would have had to ride on very different trains.”20 Britten’s case will be examined below.

From an international event involving several famous composers, Music and World Events turned its attention to the American Civil Rights movement and its signature protest song, “We Shall Overcome,” which lacks a definitive “composer.” We traced this song back to its first publication in 1901 by Charles Albert Tindley, a Methodist minister in Philadelphia—although it is not clear whether Tindley actually newly composed the song, or simply added verses to a pre-existing traditional chorus that was already well known to his congregation. The song, originally called “I’ll Overcome Someday” and later “We Will Overcome,” was taken up by a tobacco workers union on strike in South Carolina in 1945; the union leaders taught the song to Miles Horton at the Highlander Folk School in 1947. Horton had founded Highlander in Tennessee in 1932 to educate local leaders and promote racial integration. Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie learned the song at Highlander in 1947; Seeger changed “will” to “shall” and added new verses. The SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) Freedom Singers took up “We Shall Overcome” in 1960, and by this point it had become the “theme song of the [Civil Rights] Movement.”21 The song had spread not by commercial recording or sheet music sales, but by word of mouth.

At the March on Washington in August 1963, Joan Baez led the crowd in singing “We Shall Overcome.” The phrase was uttered in President Lyndon B. Johnson’s March 1965 address to Congress, urging politicians to move forward with the Voting Rights Act. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. incorporated the text of “We Shall Overcome” into his last sermon in March 1968. And finally, in November 2008, President-elect Barack Obama referenced the song in his acceptance speech in Chicago’s Grant Park—located just a few blocks away from our classroom at Roosevelt. A simple song of unsure origin with countless textual and melodic variants, sung in prisons and on picket lines, “We Shall Overcome” displays the remarkable ability of music to participate in history.

Reactions and Discussion – World History

Online resources supplemented each step of our exploration of “We Shall Overcome” and ignited discussion. Videos of the March on Washington and the speeches by President Johnson22 and President-elect Obama23 not only verified the historical relevance of the song but also imbued it with emotional gravity. I surrounded these videos with a mosaic of documentary clips, images, and sound bytes relating to the Civil Rights movement, some of them quite dramatic or even violent. Many of these images were immediately available for download and could be easily collected, arranged, annotated, distributed, and presented in a way that fit my lesson plan.

LBJ video:

Obama video:

At the halfway point in the semester, I initiated an online discussion on Blackboard, the course management system currently in use at Roosevelt. Each student was required to post at least one comment in response to my leading question “which piece studied in class so far was the most effective?” Though lacking the nuance and body language of a live discussion, this Blackboard thread provided several benefits. Students who were reluctant to speak in class now took center stage. Responses could be carefully organized, crafted, and edited. Before joining the conversation, students could review everything that had already been mentioned. The focus of the thread itself began to curve as students responded less to my original query and more to the previous comments. The discussion then branched out as respondents debated the merits of each composition that had been nominated as “most effective,” citing historical impact, musical technique, programmatic content, and emotional accessibility. One significant aesthetic sidebar struggled to pinpoint the true definition of “effectiveness.” Early in the thread, one student argued passionately for “We Shall Overcome,” explaining that its simplicity—and its ability to be improvised upon—made it extremely effective.

While these online resources and tools did not generate the content or the structure of the seminar, they enabled students to experience the sights, sounds, and emotions of these events. In “Technology and Online Sources” below, I provide several more examples demonstrating the usefulness and impact of technology in Music and World Events.

Composer Biography

I selected Britten’s War Requiem for the first week of class, partly due to chronology (the poetry selected by Britten was written during World War I) and partly because the work raises a host of fascinating questions about pacifism, message, and artistic authority. Students read about Britten’s pacifist views, his refusal to fight in World War II, and his decision to face the Tribunal for the Registration of Conscientious Objectors. In his statement to the Tribunal in 1942, Britten writes, “Since I believe that there is in every man the spirit of God, I cannot destroy, and feel it my duty to avoid helping to destroy as far as I am able, human life, however strongly I may disapprove of the individual’s actions or thoughts.”24 The War Requiem was Britten’s crowning pacifist statement; it was written for the 1962 rededication of St. Michael’s Cathedral in Coventry, which had been destroyed during the war.

For the text of the War Requiem, Britten alternated the traditional Latin Requiem Mass text with poetry by Wilfred Owen. Owen joined the English army in 1915 as a rifleman and was shot dead in November 1918, exactly one week before the close of World War I. By all accounts, Owen was a decorated and talented soldier, earning the Military Cross for capturing a German machine gun and taking “scores of prisoners.”25 In literary circles, however, Owen is considered a chief pacifist voice. Owen’s pacifism differs from Britten’s; Owen was willing to fight for defense and liberation, but not in aggression. The following excerpt is taken from the Preface to Owen’s first collection, Disabled & Other Poems (1918):

Above all I am not concerned with Poetry.

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next. All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true Poets must be truthful.26

Reactions and Discussion Composer Biography

Britten quotes this Preface on the title page of the War Requiem. Owen’s poetry and life story, along with Britten’s life story and music, generate a complex network of critical questions:

What is the definition of pacifism? Is there a single definition?

If you were in Britten’s situation, would you fight or not?

Owen claims that “All a poet can do today is warn.” What are the limits of poetry and music when it comes to war? Can art fully express the terrors of war?

What is the message of the War Requiem?

What is an artist’s role in times of war?

Must an artist suffer from a conflict to be able to comment on it authoritatively?

Through lively discussion, it became apparent that the message and source materials of a masterpiece such as the War Requiem may be more complex than first thought. Students also observed that personal and national history exert profound influence on artistic decisions.

Reception History

The creation and intention of a musical work is but one layer; we must also consider its reception history: how the work is understood and interpreted over time. After Britten, we proceeded directly to Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 7 (Leningrad). Christopher H. Gibbs wrote about the genesis and performance history of this epic work in his article “ ‘The Phenomenon of the Seventh’: A Documentary Essay on Shostakovich’s ‘War’ Symphony.”27

Several students were surprised to learn that the Soviets, in 1941, were key allies with the United States against Nazi Germany. In October 1942, the members of the New York Philharmonic sent Shostakovich a message of encouragement and solidarity, calling his symphony “a symbol of unity of all the forces of culture and progress linked together against degeneracy and barbarism of Fascism.”28 Roy Harris’s Fifth Symphony (1943) was dedicated to “our great ally, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, as a tribute to their strength in war.”29 The hype surrounding the Leningrad symphony was sensational: following the premiere in Russia in March 1942, tales emerged of a heroic Shostakovich composing feverishly amid a backdrop of gunfire, in between digging trenches and responding to fire alarms. Conductors and orchestras in the United States clamored to give the American premiere. On July 19, 1942, Toscanini led the NBC Symphony Orchestra in a live broadcast; the following day, Shostakovich’s image appeared on the cover of Time magazine, adorned with fireman’s outfit and helmet. Within weeks, Koussevitsky had given live performances with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood, with proceeds going to Russian War Relief. By January, major American orchestras had registered dozens of Leningrad performances. Shostakovich was made an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1943, and the symphony earned a Stalin Prize back home. With such an unprecedented swell of publicity, it is little wonder that Bartók mocked the symphony’s famous ostinato in his Concerto for Orchestra.

Inevitably, the Leningrad symphony suffered a precipitous decline in popularity and reputation. By 1943, the hype diminished and most critics were skeptical about the musical contents of the piece. Some complained that the piece was too large, bombastic, derivative, repetitive, and unstructured. One common thread was that the symphony’s strength lay in its message and not in the music itself.

Reactions and Discussion - Reception History

This sparked a class discussion on absolute music versus program music—particularly relevant to Music and World Events because the music studied in this class responds to extramusical narratives or occurrences. Students debated the value of a program—if the audience needs to know the program—in order for a work to be effective. Can a composer create a musical response to an external event without making the program public? Can the hype surrounding a program cheapen or distract from the work’s quality or true nature? Can a program be misinterpreted, abused, or propagandized? If students answered “yes” to any of these questions, I challenged them to present concrete examples to the class.

Theoretical Analysis and Technique

Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46 (1947), for narrator, men’s chorus, and orchestra, provides a chilling glimpse of the terror and suffering of Jewish prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp. Schoenberg himself cobbled together the text in English, German, and Hebrew, based upon “reports which I have received directly or indirectly” from Holocaust survivors.30 The title is probably a nod to the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, but the actual location of the Nazi camp in Schoenberg’s text is never explicitly stated. The dramatic nature of the music and Schoenberg’s incisive treatment of the text are inescapable. A Survivor from Warsaw is furthermore special because, within it, Schoenberg makes bold personal statements about his heritage, musical legacy, and compositional techniques.

David Isadore Lieberman, in a fascinating article entitled “Schoenberg Rewrites His Will,”31 argues that Schoenberg reassigns his compositional legacy from his Austro-German training to his Jewish heritage in late works such as A Survivor from Warsaw. Schoenberg was born into a Jewish family and converted to Lutheranism in 1898. He was ever religious, but never fretful about fully conforming to the orthodoxy of any particular religion. After experiencing acute anti-Semitism from the early 1920s, Schoenberg began to rediscover his Jewish heritage; Lieberman explains that this rediscovery is concurrent with and inextricably tied to Schoenberg’s development of the dodecaphonic serial method of composition. Following his sudden removal from his faculty post in Berlin in 1933, Schoenberg reconverted to Judaism in Paris before moving to the United States. Many of his late works center on Jewish texts and themes, namely Survivor, Kol Nidre op. 39 (1938), the choral-orchestral prelude Genesis op. 44 (1945), Israel Exists Again (incomplete, 1949), and De Profundis op. 50b (1950).

As Lieberman explains, this constitutes a seismic shift in Schoenberg’s musical thinking. Earlier, after World War I, Schoenberg had argued vehemently that his atonal compositions were not a rejection of tradition but rather the next necessarily step in the evolution of music. Schoenberg claimed his rightful place in musical tradition—specifically the unbroken German line of J.S. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and Wagner.32 Schoenberg’s “emancipation of the dissonance” from 1908 was merely the next expansion of Wagnerian chromaticism. In 1921 Schoenberg commented that serialism would ensure the primacy of German music “for centuries to come.”33 The wholly serial String Quartet no. 4, op. 37 (1936) features sonata tendencies in its first movement, with the primary theme starting on D, and the secondary theme based on a row form starting on A, a perfect fifth higher. And in his famous essay “Brahms the Progressive,” Schoenberg praised the motivic economy and inventiveness of Brahms and Beethoven (a technique he termed “developing variation”); Schoenberg applied the same motivic approach to his freely atonal and serial compositions.34 The unfinished opera Moses und Aron (1927-32), for example, is founded upon a single “motive,” which is its twelve-tone row. In several other essays Schoenberg insisted upon his music’s place as the logical continuation of German progress;35 his pupil Anton Webern, who held a Ph.D. in musicology from the University of Vienna, put forth similar arguments.36

As early as 1931, Schoenberg struggled to reconcile his German musical identity with the anti-Semitism he repeatedly experienced: “German music will not take my path, the path I have pointed out. Prepared to release myself from it, but not without having settled my debt to it, I wish as thanks to show it the path it has taken.”37 After his official reconversion to the Jewish faith, Schoenberg writes to Webern in August 1933: “During that time I was able to prepare myself for it thoroughly, and have finally cut myself off for good…from all that tied me to the Occident. I have long since resolved to be a Jew…”38 This separation reaches its fullest musical statement in A Survivor from Warsaw, in particular at its conclusion when the chorus recites the Shema Yisrael. Here, as the Jewish men proclaim their faith identity in defiance of their Nazi captors, Schoenberg masterfully structures the music upon those techniques central to his musical legacy: developing variation and serialism (the row exhibits inversional hexachordal combinatoriality, another preferred Schoenberg technique). Schoenberg had wrested his musical achievements from the German tradition and had bequeathed them to Judaism.39

Reactions and Discussion - Theoretical Analysis and Technique

After reading Lieberman’s article and studying the score of A Survivor from Warsaw, my students debated the meaning and tangibility of Schoenberg’s musical identity. Some students argued that the average listener would not be familiar with developing variation and serial methods, and would definitely not be able to perceive these features at work while listening to a performance. Appreciating this aspect of Survivor, they continued, would require an uncommon degree of knowledge, musical training, and background beyond the scope of program notes. If the average listener cannot perceive it, does it really make an impact? Other students countered that the issue of musical technique and heritage held deep personal meaning for Schoenberg, and therefore enriched the expressive contents of Survivor, whether they could be enumerated or not. This led to a larger discussion on meaning and impact: is it enough for an artwork to hold personal meaning for the creator, or must its contents and message be perceptible to a wide public?

Style

Music and World Events not only afforded opportunities to reinforce 20th-century theoretical techniques such as serialism, but it also allowed us to explore recent styles and trends. One style (or family of styles) that continually surfaced was minimalism. Students observed that perceptible processes, audible change, and accessibility are often core values of minimal music, and as such, provide a fertile framework for responding to world events and delivering social statements. (Other highly accessible frameworks such as folk music, popular music, and protest songs generally lay beyond the scope of this course, although they occasionally emerged and played a role in music by “traditional” concert composers.40)

Throughout the semester, students explored pieces from several corners of the minimalist repertoire: Reich’s Come Out (1966) and Different Trains (1988), Glass’s music for the film Koyaanisqatsi (1983), and Adams’s On the Transmigration of Souls (2002). One could possibly add Berio’s “O King” from Sinfonia (1968) for its reduced pitch materials, static harmonies, and process-oriented formal structure. Other very worthy and interesting compositions by Rzewski and Louis Andriessen were regrettably left out.41

Opera is a key arena for social commentary, and minimalist operas are exceptional in this regard.42 Due to time constraints, we only briefly discussed Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer (1991), which retells the 1985 hijacking of a passenger liner by the Palestine Liberation Front. The staging of Klinghoffer by the Metropolitan Opera during its 2014-15 season sparked a vigorous debate that spread far into public and political spheres.43 In a future semester I would like to design a similar graduate course centering on opera: Opera and World Events (I explore this possibility below in the section entitled “Outcomes and Challenges”).

According to Timothy A. Johnson, minimalism can be considered an aesthetic, a style, or a technique.44 I wanted my students to absorb all three of these possibilities. The minimalist aesthetic is chiefly represented in works from the 1960s by La Monte Young, Terry Riley (In C), and Reich. These pieces required a “new way of listening” and, unlike music from the common-practice tonal period, were not teleological or representational: they were not “goal oriented” and no longer expressed “subjective feelings” in the traditional manner. Works such as In C and Reich’s Come Out “seem to suspend time, gradually revealing a slowly unfolding process or focusing upon a minute musical detail.”45 In Come Out, Reich phases five words spoken by Daniel Hamm (“…come out to show them”), wrongly arrested for murder in Harlem in 1964.46

During the 1970s, the minimalist music of Reich and Glass branched out beyond the early process pieces and operated within a general set of common characteristics: short overlapping rhythmic and melodic fragments, diatonic triads and seventh chords, motoric rhythmic drive, long swelling formal arcs, and bright timbres. At this point, Johnson maintains, minimalism became a style, a “school of composition,” with consistent and identifiable musical parameters.47

In the 1980s, however, the music of Adams and others began to deviate from these style features while still bearing some of the marks of minimalism. This, the final and loosest stage, categorizes minimalism as a technique, which can be merged with other techniques or styles in a single composition. Adams, Andriessen, Rzewski, David Lang, Julia Wolfe, Arvo Pärt and many other living composers freely combine minimalist sections or references with elements from jazz, rock, neo-Romanticism, chant, ragtime, folksong, and other sources.

Reactions and Discussion – Style

Having observed the three stages of minimalism, my students were quick to point out its advantages and setbacks. Some found the reduced, diatonic language to be direct and accessible, while others called it bland and questioned its ability to communicate emotion or a forward-moving narrative. The repetitive nature of Glass’s Koyaanisqatsi generated a wide variety of reactions from entrancing to meditative to alarming to irritating. One student thought that Glass’s music worked well with the film, but doubted its integrity to stand alone as absolute music. Then surfaced the debate between simplicity and complexity: if music can be overly complex, could it also be too simple? Does simple necessarily mean effective? We compared Come Out with A Survivor from Warsaw. While some students found serialism and combinatoriality to be complicated and inscrutable, not one could deny that Schoenberg’s masterpiece carried dramatic potential on par with Come Out.

Aesthetics

It is easy to see how issues of aesthetics flooded the classroom discussion in every segment of the semester. Students constantly weighed compositional approaches: was there a balance point, a sweet spot for crafting the most effective response to a world event? They struggled to decide if aesthetics should carry a moral code, and if there was a “right” and “wrong” way to artistically comment on an event, especially when someone else’s suffering was involved. Some students wondered if Come Out was really Reich’s way of marketing Daniel Hamm’s pain to further his burgeoning musical career, and therefore to be considered immoral and defunct. Or, conversely, was Reich an essential, invaluable mouthpiece for bringing public awareness to Hamm’s plight? (Come Out was originally commissioned by Truman Nelson, an activist, for a benefit concert to raise funds for Hamm’s legal counsel. Hamm was later acquitted.)48

In these aesthetic discussions, two polarities emerged: program music versus absolute music (see above), and personal versus universal expression. When Adams was commissioned by Lorin Maazel and the New York Philharmonic to compose a memorial for the victims of the attacks on September 11, Adams hesitated and viewed the project as a serious aesthetic challenge. Eventually he accepted the commission and wrote On the Transmigration of Souls. “I decided that the only way to approach this theme was to make it about the most intimate experiences of the people involved.”49 Adams assembled the text from names of victims and messages found on missing-persons signs near Ground Zero. The result is a sonic environment with “millions of particles.” Adams admits that the work remains a “problematic piece for concert audiences.”50 A few of my students balked at the usage of victims’ names, and wondered if Adams had the right to “appropriate” the names as raw material for his composition. Others felt uncomfortable hearing the names because it made the tragedy too close, too real, and too specific. Or did Adams rather honor the victims by perpetuating their memory in an amplified, elevated environment? Was it a privilege to be named, or an affront?

John Corigliano, in his Symphony no. 1: Of Rage and Remembrance (1988-89), aims for a delicate balance between personal tribute and communal statement. The symphony was dedicated to eleven friends who had died of AIDS and, much like to the iconic AIDS Quilt, was also intended to be a towering symbol for the millions of lives lost to the AIDS epidemic. Among the eleven friends, some are kept anonymous, while others are named in the score but not in Corigliano’s extensive program note. Sheldon Shkolnik (1938-1990), concert pianist and the dedicatee of the first movement, was not identified in either the score or the program note, but was later named by Corigliano in interviews (Shkolnik’s family did not want the nature of Sheldon’s illness to be made public).51 The third movement was composed for a cellist friend, Giulio, but we are never told his last name. The symphony earned Corigliano two Grammy awards and a Grawemeyer Award in composition; similar to Shostakovich’s Leningrad, however, some critics assailed the music for relying too heavily on a detailed knowledge of the victims and their personal stories.52

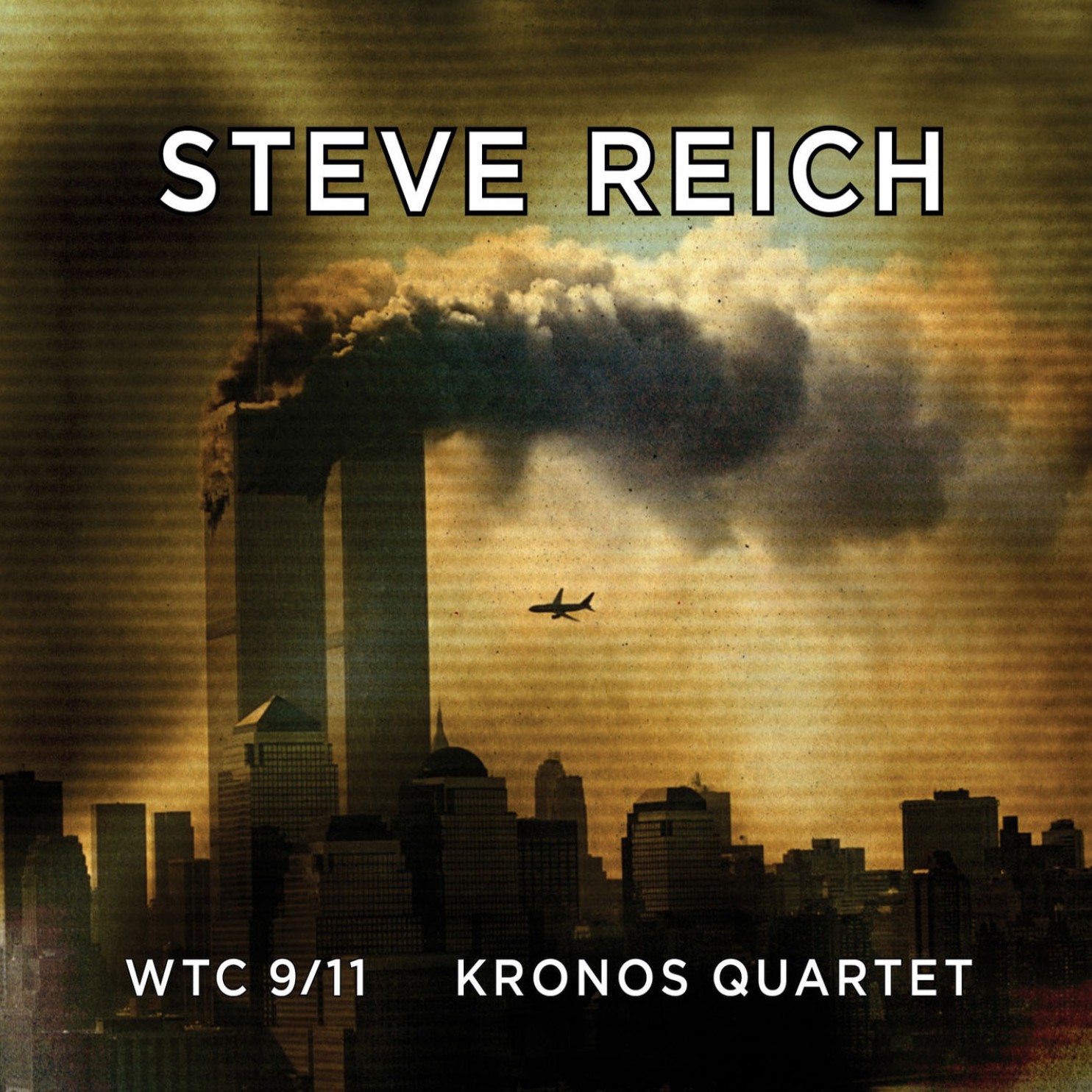

Perhaps the fiercest debate of the semester centered on Reich’s WTC 9/11 (2009-10)—not the nature of the music itself, but the imagery on the original album cover. First released by Nonesuch Records in July 2011, the album jacket clearly showed the twin towers during the attacks of September 11, billowing with smoke and with the second airplane close on the approach. After enormous pushback,53 Reich issued a statement through the Nonesuch official website in August 2011 and the cover was changed.54 Below you will see the original and new covers.55

Reactions and Discussion - Aesthetics

My students then unknowingly reenacted the very public debate between listeners who accepted the rawness of the original cover and those who decried its appearance on an album for commercial sale.56 It seemed as if the very essence of the course, Music and World Events, was now fully expressed right in front of us in these two images. I asked the class if we were reacting in an especially visceral way to WTC 9/11 because this particular event was relatively recent and proximate, having occurred on American soil. Would the original album cover become more acceptable at a greater distance, after a few more decades have passed? Do we apply our aesthetic criteria fairly across all media, and do we also object to major motion pictures or documentaries that feature the same explicit images? Can one tragedy claim precedence over another? Can world events be measured or compared?

Technology and Online Sources

The availability of videos, images, interviews, DVDs, and interactive online sources strengthened the impact of the course material. Students gained proximity to the events, composers, and performers. For example, an updated DVD release of Koyaanisqatsi by The Criterion Collection offers supplemental materials, including a feature interview with director Godfrey Reggio. Reggio describes the goals of the film, hints at its core messages, and even details his unique collaboration with Glass.57 The film also provided a platform for discussing changes to the environment vis a vis the benefits and dangers of technology.

In another example, a 2007 interview with George Crumb (see below) laid the groundwork for our study of Black Angels (1970), composed in reaction to the Vietnam War.58

Online resources were particularly helpful when working with lesser known events and composers. In the seventh week of class, we explored Exemplum in Memoriam Kwangju (1981), a large orchestral poem by Korean composer Isang Yun (1917-1995). Yun’s piece responds to a massacre that took place in May 1980 in Kwangju, a mid-size city in the southwestern corner of the Korean peninsula.

I assigned two readings on the history of the Kwangju Massacre (variously termed the Kwangju Uprising and the Kwangju Democratic Exercises).59 In October 1979, the Park Chung Hee, president of South Korea, was assassinated by the chief of the Korean CIA. Park had seized political power through a military coup in 1961, and despite ruling as a dictator, enjoyed popular support for several years through his successful economic policies (Park was also the father of South Korea’s current president, Park Geun-Hye). By the late 1970s, however, an economic slowdown and other political crises undermined Park’s popularity and weakened the ruling party. Many citizens who had protested Park’s authoritarian methods expected a wave of democratic reform after his sudden death. Instead the opposite happened: in December 1979, in another coup, General Chun Doo Hwan seized complete control. Amid public unrest and widespread protests in spring 1980, Chun placed the entire country under martial law, suspending parliament.

On May 18, 1980, students in Kwangju began to protest at Chonnam National University. The university had been closed by martial law, and military troops blocked the students from entering. As the protest gained steam, military paratroopers violently stormed the students with batons, clubs, bayonets, and knives. The students and citizens collected themselves, organizing larger protests on the afternoon of May 18 and the morning of May 19. By May 20, the “whole city was in an uproar.”60 For a time, the citizens formed a makeshift militia that managed to keep the troops at bay. A committee was formed on May 22 to establish negotiating terms with the government. Until May 26, the people of Kwangju survived under tenuous self-rule, mobilizing resources and donating blood to meet the needs of the community. Early on May 27, however, the Korean military stormed Kwangju with guns and thirty tanks. The Kwangju movement was officially crushed; by the end, 170 people were reported dead and 380 injured.61

The written account is harrowing enough. But the students did not fully grasp the terrifying reality of the Kwangju Massacre until they watched the videos.62

How does Isang Yun play a role in this? I wanted to go deeper than mere association; he was more than Korean composer writing music about something that had happened in Korea. Yun had actually been active during World War II in the resistance against Japanese forces who were occupying Korea. After the Korean War, he moved to Paris and later Berlin to forward his career. In 1967, he was suddenly abducted by Park Chung Hee’s government, transferred to Seoul, and charged with Communism. Due to mounting international pressure, he was released in 1969 and granted amnesty in 1970. More than a composer, Yun was a trailblazer and one of Korea’s most powerful artistic voices from the last century. His “fundamental aim” was the “develop Korean music through Western means.”63

Exemplum in Memoriam Kwangju is a rich, dense, and vibrant orchestra score. We analyzed Yun’s harmonic language, his penchant for balancing two or three textural layers (or “energies”), narrative symbolism attendant in the formal structure, and his careful manipulation of rhythmic elements. Lyrical, passionate, martial, and meditative elements both recount the events in Kwangju and reflect upon them. Another valuable online resource, a 1987 interview with Yun, reveals his larger views on spirituality, creativity, and the compositional process.64 The availability of online materials in Music and World Events brought the students face-to-face with the events and composers shaping the course, providing a satisfying level of depth and context. These videos and interviews emphasized the human element and helped the students to connect with the individuals involved.

Outcomes and Challenges

Student feedback for Music and World Events was generally positive. The combination of musical works and historical events presented a new approach to study and held student interest. The course material invited student participation and easily connected with current events in real time. Our examination of “We Shall Overcome” and the Civil Rights Movement naturally led us to discuss Barack Obama’s presidency. As we considered Corigliano’s symphony and the stigma of homosexuality and AIDS in the United States (particularly in the 1980s), the Supreme Court deliberated the Defense of Marriage Act. When studying the Kosovo War of 1998-99, we read about CNN’s coverage of the war and debated the ongoing practices and objectivity of the American news media.65

Multiple students reported that the course load was heavy, and that the required world history textbook was either too broad or too detailed. Some recommended dropping the textbook altogether to better focus on the musical content. The routine of textbook, musical readings, and critical responses could have been refreshed by including quizzes, brief presentations, or small group activities. Since the grading was so heavily weighted towards the final project, some students desired more assignments along the way to provide feedback and balance their overall grade.

Time management proved to be the most daunting challenge. Lesson plans needed to balance historical background, musical analysis, composer biography, and the other contexts mentioned above. I am not sure that I achieved a successful balance; one student astutely observed that the first half of the semester was centered on the music itself, but the second half became immersed in contextual readings and composer biography. During the World War II unit, I conveniently assigned one single textbook reading to account for the entire war. Later in the semester, however, we required new historical context each week, as we quickly progressed from event to event (the Civil Rights Movement, Kwangju, the Vietnam War, the AIDS crisis, the Kosovo War, September 11, and more). And with the abundance of online resources discussed earlier, it was often difficult choosing which contextual material to include, and which to leave out.

Opinions were split on the final project. Some students were simply “not sold” on it. Can completing a research paper and a creative response truly transform a student into an artist-citizen? Not necessarily, but other students reported that the project was transformative and pushed them beyond their experience and comfort zone. Several students were proud of their creative work, and in many cases they worked in a medium that they had never tried before. In retrospect, I should have scheduled a Music and World Events concert for the students’ creative responses, so that all of the creative work could have been presented to the public at once, instead of cramming each performance into a single time block together with the research presentation.

Music and World Events Since 1945 was far from perfect, and the shape and contents of the course are by no means fixed. The model could feasibly function for any time period, featuring particular genres (such as popular music, chamber music, or opera as mentioned above), with ever-shifting repertoire and historical inclusions. Even within my stated timeframe, the syllabus suffers from many glaring omissions: Rzewski, Andriessen, Messiaen, Husa (Music for Prague 1968), and Henze (El Cimarrón) all deserve a place. Surely the reader will easily supply several important works that I have not included.

Moreover, the coupling of musical study with world history could theoretically be infused into pre-existing courses without serious disruption. The Music and World Events concept could perhaps be presented as a four-week unit within an undergraduate analysis or history course, a graduate literature survey, or a freshman seminar. The reach and rigor of the materials may be adjusted to accommodate varying levels, formats, and timeframes.

In this article and in the course, I posed many more questions than I answered. After completing the course, however, I am convinced that the masterworks of the past remain a guiding light for the artist-citizens of the present. From these works we glean the techniques, styles, formal structures, and aesthetic strategies for effective communication and civic engagement. My primary goals of social awareness and empowerment are best exemplified in the music of composers such as Britten, Shostakovich, Schoenberg, Yun, Reich, Corigliano, and Adams. In some cases, the music embodies a power that extends beyond the reach of the event itself. A study of past works, through the lens of world history, is essential for harnessing and developing that power in today’s emerging artist-citizens.

Repertoire List

(Compositions listed in the order in which they were presented in class.)

Britten, War Requiem, op. 66

Shostakovich, Symphony no. 7, Leningrad, op. 60

Prokofiev, Symphony no. 5, op. 100

Schoenberg, A Survivor from Warsaw, op. 46

Poulenc, Figure humaine

Reich, Different Trains, Come Out, WTC 9/11

Berio, “O King” from Sinfonia

Olly Wilson, A City Called Heaven

Crumb, Black Angels

Glass, Koyaanisqatsi (film)

Isang Yun, Exemplum in Memoriam Kwangju

Corigliano, Symphony no. 1: Of Rage and Remembrance

Drinor Zymberi, Epitaphs

Adams, On the Transmigration of Souls

Stephen Hartke, Symphony no. 3

Joan Tower, In Memory

Kyong Mee Choi, The Eternal Tao

Stacy Garrop, In Eleanor’s Words66

________________________________________________________________

Notes

1Roosevelt University, “Institutional Strategic Plan,” http://www.roosevelt.edu/About/StrategicPlan/Who.aspx (accessed December 27, 2014).

2Joseph W. Polisi, The Artist as Citizen (Milwaukee: Amadeus Press), 2004.

3Angela Myles Beeching, Beyond Talent: Creating a Successful Career in Music (New York: Oxford University Press), 2010.

4Sharing Notes, “Home Page,” http://www.sharing-notes.org (accessed December 31, 2014).

5Civic Orchestra of Chicago, “Citizen Musician,” Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, http://citizenmusician.org (accessed December 31, 2014).

6Merit School of Music, “Alice S. Pfaelzer Tuition-free Conservatory,” http://meritmusic.org/alice-s-pfaelzer-conservatory/#.VKSoRodx1ZE (accessed December 31, 2014).

7Fifth House Ensemble, “OneShot! Concerts,” http://fifth-house.com/programs/one-shot-concerts/ (accessed December 31, 2014).

8Patricia Shehan Campbell, “Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major,” Symposium 54 (October 2014), http://www.music.org/pdf/tfumm_report.pdf (accessed December 31, 2014): 1.

9Ibid., 3.

10Karen Eng, “Classic rock: Dan Visconti, the 21st-century composer,” TED Blog, http://blog.ted.com/2014/05/23/dan-visconti-and-a-new-breed-of-21st-century-composer/ (accessed December 31, 2014).

11Maynard Solomon, Mozart: A Life (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 285-306. See the selected bibliography (606-607) for several sources specifically dealing with Mozart’s operas.

12Campbell, “Report,” 12.

13R.R. Palmer, Joel Colton, and Lloyd Kramer, eds., A History of the Modern World, Volume 2, 10th edition (New York: McGraw Hill, 2006).

14Ibid., 827-864.

15Christopher H. Gibbs, “ ‘The Phenomenon of the Seventh’: A Documentary Essay on Shostakovich’s ‘War’ Symphony,” in Shostakovich and His World, ed. Laurel Fay (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 59-113.

16Daniel Jaffé, Sergey Prokofiev (London: Phaidon Press, 1998), 168-184.

17Carl B. Schmidt, Entrancing Muse (Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon Press, 2001), 286-291; Benjamin Ivry, Francis Poulenc (London: Phaidon Press, 1996), 116-140.

18Oliver Neighbour, Paul Griffiths, and George Perle, The New Grove Second Viennese School (New York: W.W. Norton, 1980), 14-15.

19Camille Crittenden, “Texts and Contexts of A Survivor from Warsaw, Op. 46,” in Political and Religious Ideas in the Works of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Charlotte M. Cross and Russell A. Berman (New York: Garland Publishing, 2000), 231-238.

20Steve Reich, Writings on Music 1965-2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 151.

21Bernice Johnson Reagon, “The Civil Rights Movement,” in African American Music: an Introduction, ed. Mellonee V. Burnim and Portia K. Maultsby (New York: Routledge, 2006), 606-609.

22LBJ Library, “Address before Joint Session of Congress, 11/27/63. MP505,” May 23, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LF0TxpxIMA0 (accessed March 11, 2015).

23CNN, “Raw Video: Barack Obama’s 2008 acceptance speech,” November 6, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LEo7lzfpdCU (accessed March 11, 2015).

24Mervyn Cooke, Britten: War Requiem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 15.

25Ibid., 9.

26Ibid., 10.

27Gibbs, “‘The Phenomenon of the Seventh,’” 59-113.

28Ibid., 88.

29Ibid., 100.

30Crittenden, “Texts and Contexts,” 231.

31David Isadore Lieberman, “Schoenberg Rewrites His Will,” in Political and Religious Ideas in the Works of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Charlotte M. Cross and Russell A. Berman (New York: Garland Publishing, 2000), 193-229.

32Ibid., 195-198.

33Ibid., 195.

34Schoenberg showed signs of motivic construction as early as Verklärte Nacht, op. 4 (1899), but heavy structural reliance upon a single motive came to the fore in Drei Klavierstücke, op. 11, no. 1 (1909), Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, op. 15 (1908-09), and “Nacht” (no. 8) from Pierrot Lunaire, op. 21 (1912). For more on the Second Viennese School’s approach to motive, see: Janet Schmalfeldt, “Berg’s Path to Atonality: The Piano Sonata, op. 1” in Alban Berg: Historical and Analytical Perspectives, ed. David Gable and Robert P. Morgan (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991).

35Lieberman, “Schoenberg Rewrites His Will,” 195. See especially “National Music” (1931), “Composition with Twelve Tones” (1941) and “My Evolution” (1949); these essays and “Brahms the Progressive” can be found in Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Leonard Stein, trans. Leo Black (New York: St. Martin’s, 1975).

36Neighbour, Griffiths, and Perle, Second Viennese School, 90, 120-123; Anton Webern, The Path to the New Music, ed. Willi Reich, trans. Leo Black (Bryn Mawr, PA: Theodore Presser, 1963).

37Lieberman, “Schoenberg Rewrites His Will,” 209.

38Ibid., 210.

39Ibid., 218-220.

40In our unit on the Civil Rights Movement, we briefly surveyed the art song of Harry Burleigh (1866-1949) and “third stream” (classical-jazz crossover) compositions by Olly Wilson (b. 1937), notably A City Called Heaven (1988).

41I had intended to include Rzewski’s The People United Will Never Be Defeated! (1975) and “Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues” from North American Ballads (1978-79). Louis Andriessen’s Workers Union (1975) was also a consideration.

42One need only survey the major operatic works of Glass and Adams to sense an intense interest in world events: Glass’s Satyagraha (1979, based on the life of Gandhi); Adams’s Nixon in China (1985-87), Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic (2004-05, centering on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project). In his autobiography, Adams laments being termed a “current events” composer, calling the label “pejorative.”

43Michael Cooper, “Protests Greet Metropolitan Opera’s Premiere of ‘Klinghoffer,’” New York Times, October 20, 2014; Verena Dobnik, “Rudy Giuliani, George Pataki and 2 Congressmen Plan Protest of ‘The Death of Klinghoffer’ At Metropolitan Opera,” Huffington Post, October 20, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/10/20/metropolitan-opera-protest_n_6012836.html (accessed December 31, 2014).

44Timothy A. Johnson, “Minimalism: Aesthetic, Style, or Technique?” The Musical Quarterly 78, no. 4 (Winter 1994), 742-773.

45Ibid., 745.

46Reich, Writings, 22.

47Johnson, “Minimalism,” 747-8.

48Reich, Writings, 22.

49John Adams, Hallelujah Junction: Composing An American Life (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 265.

50Ibid., 266.

51Obituary, “Sheldon Shkolnik, 52, A Concert Pianist, Dies,” New York Times, March 27, 1990; John von Rhein, “Absent Friends,” Chicago Tribune, March 11, 1990.

52Edward Rothstein, “Themes of AIDS and Remembrance in Corigliano’s Symphony,” New York Times, January 11, 1992.

53Anne Midgette, “Reich bows to protest of 9/11 CD cover art,” Washington Post, August 12, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/reich-bows-to-protest-of-911-cd-cover-art/2011/08/11/gIQA22py9I_story.html (accessed December 31, 2014).

54Steve Reich, “Steve Reich Comments on the ‘WTC 9/11’ Album Cover,” Nonesuch Records, http://www.nonesuch.com/journal/steve-reich-comments-on-the-wtc-911-album-cover-2011-08-11 (accessed December 31, 2014).

55The image of the original cover can be viewed in the Midgette Washington Post article cited above (see note 53). Nonesuch Records now displays the new image on their official website: http://www.nonesuch.com/albums/wtc-911-mallet-quartet-dance-patterns (accessed December 31, 2014).

56Seth Colter Walls, “Looming Towers,” Slate, http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2011/07/looming_towers.html (accessed December 31, 2014).

57Godfrey Reggio, The Qatsi Trilogy, DVD (The Criterion Collection CC2215D, 2012).

58West Virginia Public Broadcasting, “An Interview with George Crumb,” produced by Anna Cole and Russ Barbour, December 21, 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5xo8SHjTxpc (accessed January 2, 2015).

59Gi-Wook Shin, “Introduction” in Contentious Kwangju: The May 18 Uprising in Korea’s Past and Present, ed. Gi-Wook Shin and Kyung Moon Hwang (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), xi-xxxi; Don Baker, “Victims and Heroes: Competing Visions of May 18” in the same volume, 87-107.

60Shin, “Introduction,” xvi.

61Ibid., xvii.

62MBC, “33 Years Ago Today,” May 28, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eAPU9njG7_s (accessed January 2, 2015); MBC Productions, “5.18 Democratic Uprising,” January 30, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LiGuYGF5dq8 (accessed January 2, 2015); CBS Christian Now, “I Was Suppressed on 5.18,” May 18, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V2nIyPaXU20 (accessed January 2, 2015).

63H. Kunz, “Yun, Isang,” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007-15), http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/30747 (accessed January 2, 2015).

64Bruce Duffie, “Composer Isang Yun: A Conversation with Bruce Duffie,” 1987, http://www.bruceduffie.com/yun.html (accessed January 2, 2015).

65Seth Ackerman and Jim Naureckas, “Following Washington’s Script: The United States Media and Kosovo” in Degraded Capability: The Media and the Kosovo Crisis, ed. Philip Hammond and Edward S. Herman (Sterling, VA: Pluto Press, 2000), 97-110; Edward S. Herman and David Peterson, “CNN: Selling Nato’s War Globally” in the same volume, 111-122.

66Dr. Kyong Mee Choi and Dr. Stacy Garrop are distinguished colleagues and professors of composition at Roosevelt University. On April 4, 2013, Dr. Choi presented her multimedia opera The Eternal Tao to the class and answered questions. On April 11, 2013, Dr. Garrop led a similar session on In Eleanor’s Words, her song cycle celebrating the life and accomplishments of Eleanor Roosevelt.