Introduction

At the 2013 ATMI National Conference, the CMS/ATMI Music Technology Lecture treated attendees to the research of Mitchel Resnick. In his lecture, Resnick, who directs the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Laboratory, detailed his investigations into how new technologies can engage people in creative learning experiences. Resnick has stated, “I believe that digital technologies, if properly designed and supported, can extend the kindergarten approach, so that learners of all ages can continue to learn in the kindergarten style–and, in the process, continue to develop as creative thinkers.”1 Resnick’s kindergarten approach essentially models a child’s activities in a traditional kindergarten classroom, where students “are constantly designing, creating, experimenting, and exploring.”2 His learning theory immediately appealed to me, as an instructor of instrumental and choral arranging courses, as many of the same components of his model are inherent in arranging music. Resnick’s presentation provoked the question: can organized use of his Lifelong Kindergarten model stimulate creative learning experiences in a typical college-level arranging course, a music course that could potentially benefit from the principles of this approach?

Background

Resnick and his research group at the MIT Media Lab have been dedicated to developing new technologies that support creative learning for nearly 30 years. The research laboratory attests it “is committed to looking beyond the obvious to ask the questions not yet asked–questions whose answers could radically improve the way people live, learn, express themselves, work, and play.”3 Past endeavors by Resnick and his group have included collaborative efforts with the Lego Group on robotic construction kits and the development of Scratch, software that allows children to program “their own interactive stories, games, and animations” in a “vibrant online community.”4 In the past seven or so years he has written frequently on extending the kindergarten style of learning to students of all ages, provided they have the correct tools. His writings draw heavily on the work of Seymour Papert, most notably on Papert’s theory of constructionism.5 His work also commonly cites the first kindergarten opened in 1837 by Friedrich Froebel, who filled his classroom “with physical objects (such as blocks, beads, and tiles) that children could use for building, designing, and creating.”6 Resnick believes these raw materials for spurring creativity have gone away in kindergarten classrooms:

In today's kindergartens, children are spending more and more time filling out worksheets and drilling on flash cards. In short, kindergarten is becoming more like the rest of school. Exactly the opposite needs to happen: We should make the rest of school (indeed, the rest of life) more like kindergarten.7

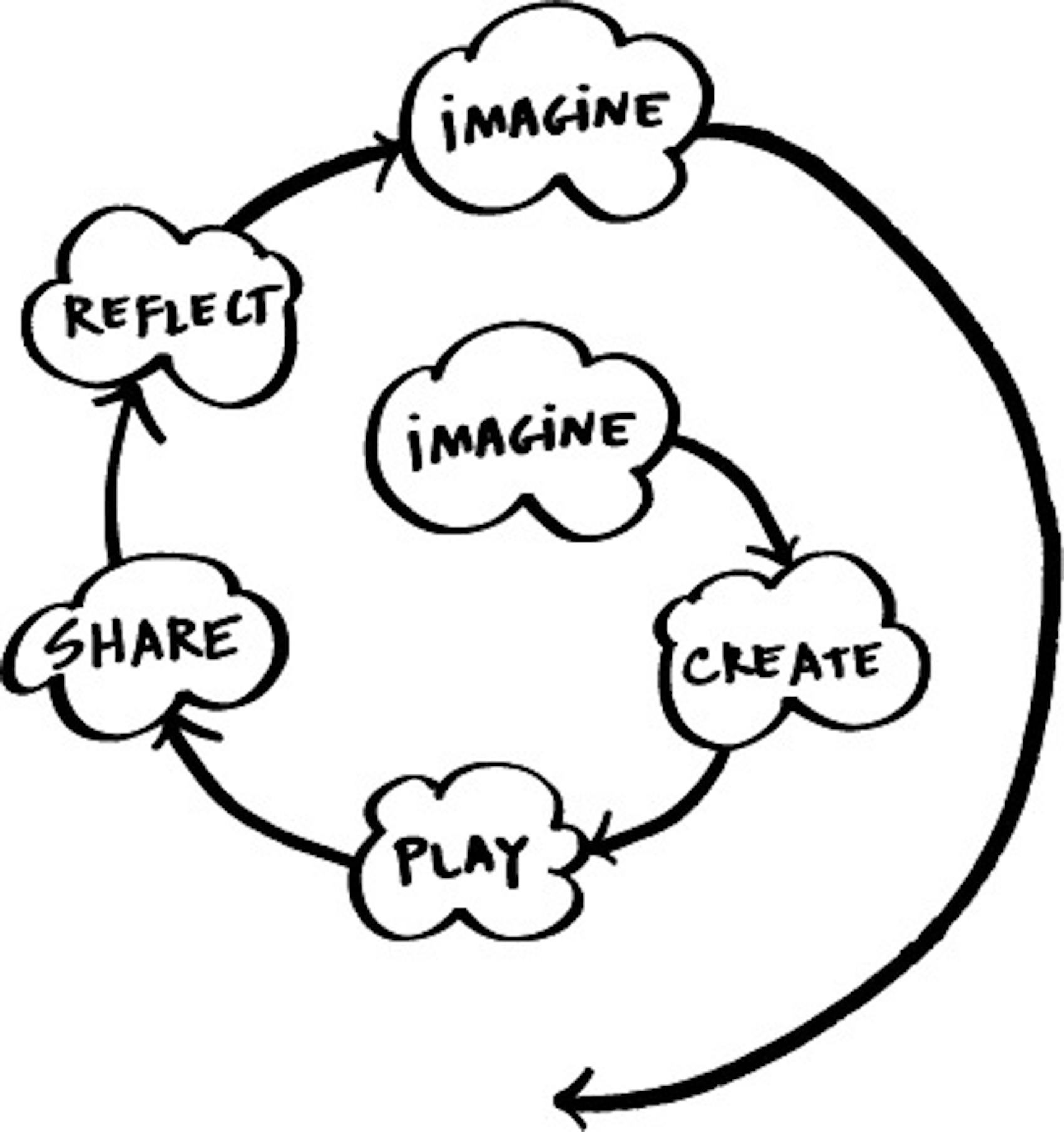

The “creative thinking spiral” is central to Resnick’s kindergarten approach to learning.8 Shown in Figure 1, his spiral models “the type of process that is repeated over and over in kindergarten. The materials vary (finger paint, crayons, bells) and the creations vary (pictures, stories, songs) but the core process is the same.”9

Figure 1: Resnick’s “creative thinking spiral,” used by kind permission from the author.10

Resnick instantiates the connection of his spiral within a traditional kindergarten classroom:

Underlying traditional kindergarten activities is a spiraling learning process in which children imagine what they want to do, create a project based on their ideas (using blocks, finger paint, or other materials), play with their creations, share their ideas and creations with others, and reflect on their experiences–all of which leads them to imagine new ideas and new projects.11

Though all concepts involved in Resnick’s spiral are naturally associated with the music-arranging process, the idea of using technology to simplify and facilitate the playing and sharing components were particularly appealing to this study. Resnick is quick to point out that his spiral is consistent with Jean Piaget’s proclamation that “Play is the work of children,”12 and he has recently written on the importance of “tinkerability” in building creative-thinking skills. He characterizes tinkering as “a playful, experimental, iterative style of engagement, in which makers are continually reassessing their goals, exploring new paths, and imagining new possibilities.”13 Resnick and Eric Rosenbaum also state:

Sometimes, tinkerers start without a goal. Instead of the top-down approach of traditional planning, tinkerers use a bottom-up approach. They begin by messing around with materials (e.g., snapping LEGO bricks together in different patterns), and a goal emerges from their playful explorations (e.g. deciding to build a fantasy castle).14

Indeed, this quote may resonate with students attempting initial arranging assignments. Though they study many scores, read pages of recommendations and tips in literature, and are encouraged to build plans for their arrangements, they still often struggle with initial decisions. For example, a student setting out to rework a piano prelude in their first wind ensemble arrangement might wonder, “If I place the accompaniment in the low brass, how do I choose what instrument carries the melody?” The student might approach their peers to play the melodic passage on their instrument to hear how it sounds, or with notation software they might transfer the melody to different instruments and listen to and imagine the effectiveness of each placement. If this iterative tinkering yields a satisfactory setting, the student might then find that a goal emerges for adding percussion to enhance the communication between the melody and accompaniment. Tinkering with potential ideas is intrinsically linked to the art of arranging, as the many questions that arise may be best confronted by playing with as many solutions as possible. Likewise, arranging courses often place specific importance on sharing their ideas with not only their classmates, but also performers not involved in the course. For instance, a wind player arranging their first string quartet may study conventions as guided by their instructor and text, but they are also encouraged to take their parts to string players. Therefore, a controlled, technology-facilitated mechanism for executing Resnick’s complete spiral served as the impetus for this study.

Before turning to the details of this study, it is important to mention that Resnick’s spiral is also connected to other recent and relevant literature dedicated to similar ideologies of “making” and “playing.” First, Margaret Honey and David Kanter’s edition Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators (2013), aspires to “serve as a resource for policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and program developers.”15 The edition includes numerous perspectives, including the “tinkering” of Resnick and Rosenbaum, that provide evidence-based research to, “rekindle this natural motivation to learn by designing environments that are supportive, that engage learners in meaningful activities, that lessen a student’s anxiety and fear, and that provide a level of challenge matched to students’ skills.”16 Second, Chris Anderson’s Makers: the New Industrial Revolution (2012) details the important growing community of “thousands of entrepreneurs emerging today from the Maker Movement who are industrializing the do-it-yourself (DIY) spirit.”17 The movement has grown in our culture with the assistance of technology, and more specifically, the presence of Make magazine and Maker Faires showcasing the movement.18 Anderson mentions forces underlying the movement include “the emergence of digital tools for design” and “collaboration.”19 Resnick points out the importance of the Maker Movement as well as he explains, “the enthusiasm surrounding the Maker Movement provides a new opportunity for reinvigorating and revalidating the progressive-constructionist tradition in education.”20 Finally, the edited collection Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children’s Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth (2006) by Dorothy Singer, Roberta Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, takes an overall similar position to Resnick by calling for the return to Piaget’s importance on play. The edition, which likewise includes a contribution by Resnick, provides compelling evidence that “play is a powerful teaching tool.”21

Research Questions

In the spirit of Resnick’s kindergarten approach to learning, this case study sought to teach two arranging courses while modeling his “creative thinking spiral.” The study hoped to provide insight on two primary questions:

1. Is Resnick’s Lifelong Kindergarten approach, in the “creative thinking spiral," effective in stimulating creative learning experiences in a college music-arranging course?

2. Do the readily available technologies Noteflight and blogs enable the Lifelong Kindergarten approach and this spiral to be present in such a course?

Subjects Involved in Study, Technologies, and Methodology

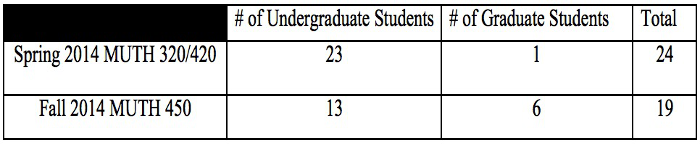

This study took place in two different arranging courses at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville (UTK) School of Music during the calendar year 2014. The two courses included a spring semester joint MUTH 320-420 course, which combines Instrumentation and Orchestration, and a MUTH 450 Choral Arranging course held during the fall semester.22 The subjects included undergraduate and graduate students in each course (see Table 1).23

Table 1: Student Participants

The study gathered feedback from the students enrolled in the above courses to evaluate their perceived effectiveness of Resnick’s spiral (to stimulate creative learning experiences), and, to assess if they thought the technologies selected were appropriate for the design. Each class used the same technologies and were each given four assignments to complete within the spiral. The study employed two widely used pieces of web-based software: Noteflight and Blackboard (for blogs). All students enrolled in the course received free Noteflight licenses; the Music Theory & Composition area requested licenses be purchased through the UTK Tech Fee. Student licenses were housed in a unique “Noteflight @ UTK” page through Noteflight Campus so that students in the course could easily share scores with each other. Noteflight Campus enabled students to access all of Noteflight’s Crescendo premium features.24 Blackboard Learn 9.1, Service Pack 14 facilitated course management and enabled blogging for this project, though any course management system and blog tool could have been used.25

The technologies utilized in this study were selected after both careful investigation of potential software available and consideration of Resnick’s suggestions for setting up the spiral. First, the web-based music notation software Noteflight, which enables cloud score storage, was selected for creating, playing with, and sharing scores. Though other—and more powerful—notation software is available to the students it was determined that Noteflight’s simplified user interface and mechanism for score exchange might be ideal for facilitating the spiral. In addition, Noteflight was selected because it had the potential to integrate what Resnick and Rosenbaum define as three core principles guiding designs for tinkerability:

1. Immediate Feedback: Noteflight enables students to “see” and “hear” the results of each decision

2. Fluid Experimentation: the simplified notation software has a small learning curve compared to others yet still allows for a wide variety of arranging possibilities

3. Open Exploration: the software has a sizable assortment of sounds, templates, and notational tools; it also allows students to improvise, adapt, and iterate26

Second, blogging was selected for reflecting on and re-imagining their work. After completing their arrangements, students reflected on them by writing one-paragraph blog entries entitled “Tips for Doing this Assignment.” The tip writing modeled Resnick’s own procedure for provoking reflection while testing his Cricket technology with students.27 The students also blogged in another paragraph which was required to begin with “I imagine in reworking I would….” All blogs in each course were shared openly with the entire class in Blackboard.

Though details regarding course material and textbooks differed, the two courses used the same methodology in each assignment.28 Due to time constraints and the number of arrangements each class needed to accomplish in a semester, projects only used one complete cycle of the spiral and closed by reimagining what would come next.

• Imagine: students studied the assigned source material and imagined possible treatments of all musical parameters including texture, dynamics, extended techniques, etc.

• Create: students created arrangements using Noteflight software on any computer

• Play: students played back and “tinkered” with their arrangements in Noteflight

• Share: students shared their arrangements to our closed course community in Noteflight; all students were required to listen to and initial each of their peers’ arrangements in the “Comments” pane of scores; they weren’t required to critique, but encouraged to do so

• Reflect: students used Blackboard to write a one-paragraph blog entry addressing “tips for doing this assignment.”

• Imagine: students used Blackboard to write a one-paragraph blog entry exploring “I imagine in reworking I would….” They were encouraged to continue to rework their arrangements and to continue the spiral.

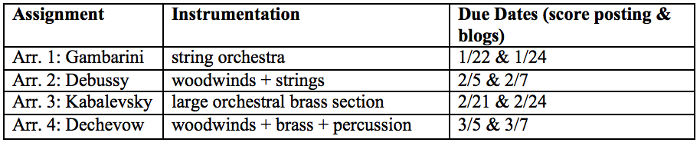

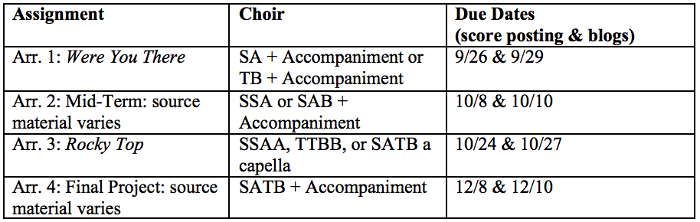

The arranging projects in MUTH 320-420 were moderate-sized (20–60 measures) excerpts from well-known composers (see Table 2). All MUTH 320-420 students arranged precisely the same measures from each excerpt in assignments. They were allowed to use the assigned instrumental forces however they wished when transferring the music from the piano reductions. The arranging projects in MUTH 450 were complete arrangements using short hymns, traditional songs, and popular works (see Table 3). MUTH 450 students were assigned two specific songs to arrange and they selected two others; they were likewise allowed to use the assigned forces however they desired. The starting and ending points for MUTH 450 arrangements were a bit different from MUTH 320-420 assignments due to the contrasting assignment objectives for the two courses. MUTH 450’s assignments guided students in developing complete choral arrangements across several short sections (e.g. verse, chorus) of pieces. The arranging forces throughout the semester remained voices and piano. In contrast, MUTH 320-420’s assignments did not specifically require students to develop relationships across many sections of a piece (though many were prepared to do this after taking the course). Unlike MUTH 450, MUTH 320-420 students worked with a variety of instrumental forces during the semester. Though differences in size and scope of assignments varied between the two courses, they shared a common trait: all students reworked pre-existing music in the open, exploratory nature promoted by Resnick. True, projects in the two courses were not completely open because they used pre-existing compositions, as their central focus rested on the arranging process. But their models reflected Resnick’s efforts to utilize “technologies that not only have a low floor (easy to get started with) and a high ceiling (opportunities for increasingly complex explorations over time), but also…‘wide walls’ – that is, technologies that are accessible and inviting to children with all different learning styles and ways of knowing.”29

Table 2: Arrangement Assignment Schedule for MUTH 320/420, Spring 2014

Table 3: Arrangement Assignment Schedule for MUTH 450, Fall 2014

At the end of each course the students filled out anonymous questionnaires using SurveyMonkey web software regarding their experiences working within the model.30 One class day at the beginning of each semester was dedicated to explaining Resnick’s research, his approach, and the class’ plans for modeling the spiral. Students were told that their feedback would have no affect on their grades and that their honest and fair evaluation of the study was appreciated. Since both classes included a vast range of prior arranging experience (e.g. from juniors to second-year Masters students) projects were not able to rigorously control and quantify the amount of learning from the spiral. However, the questionnaires were able to provide assessment of the students’ perceived learning both quantitatively (through Likert-scale questions) and qualitatively in open-ended questions.

Examples of Student Work

The figures and audio figures here represent examples of each step of the spiral in MUTH 320-420 and MUTH 450 courses.

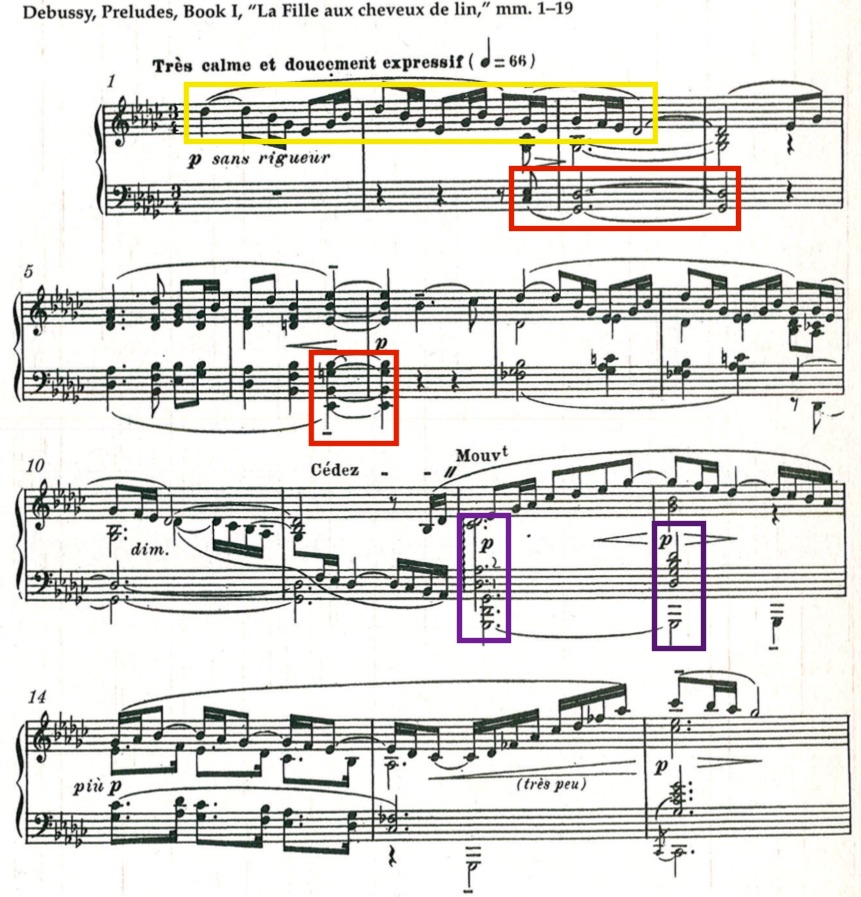

Figure 2: Example of a student’s suggestions in discussion with instructor during the imagine phase of Assignment 2 in the MUTH 320-420 course. The boxed annotations on the image reflect the student’s ideas on what instruments should carry the highlighted areas in this arrangement of Debussy’s “La fille aux cheveux de lin,” including oboe (yellow), strings (red), and woodwinds + strings (purple). Assignment from: Adler, Workbook for the Study of Orchestration, 69.

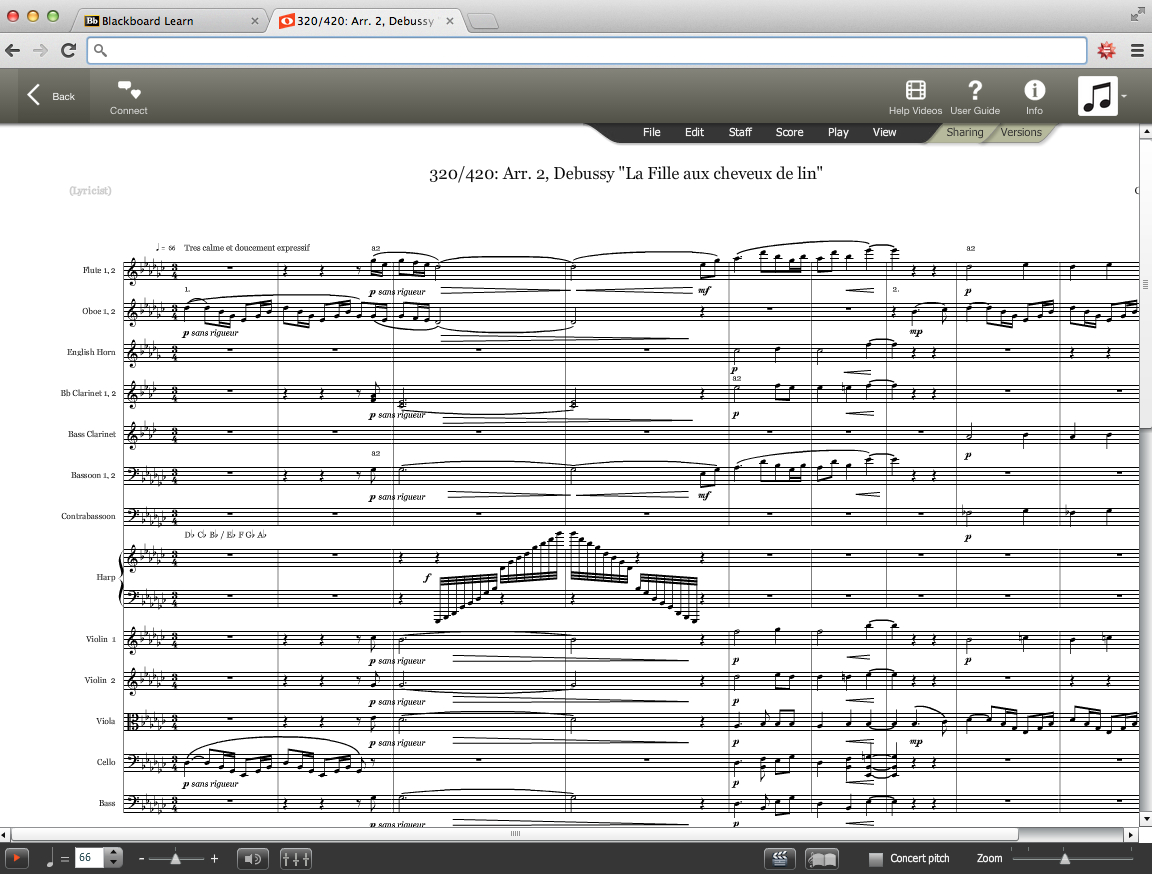

Figure 3: Example of the same MUTH 320-420 student creating their work based on the ideas shown in Figure 2. Used by kind permission from the student.

Audio Example 1: Completed Arrangement from Figure 3

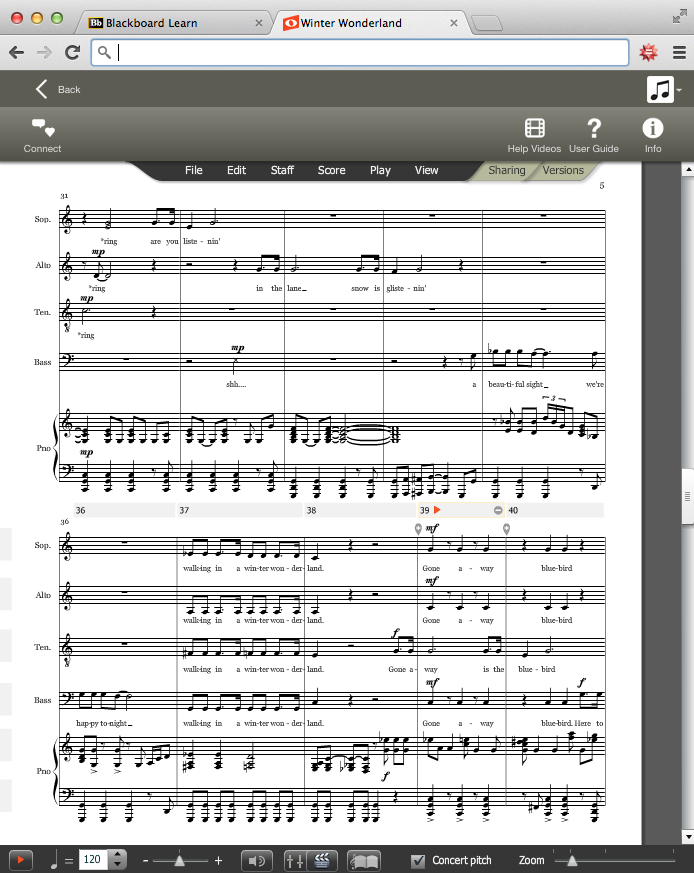

Figure 4: Example of a MUTH 450 student playing with possible interactions within the choral texture of “Winter Wonderland.” Used by kind permission from the student.

Audio Example 2: Completed Arrangement from Figure 4

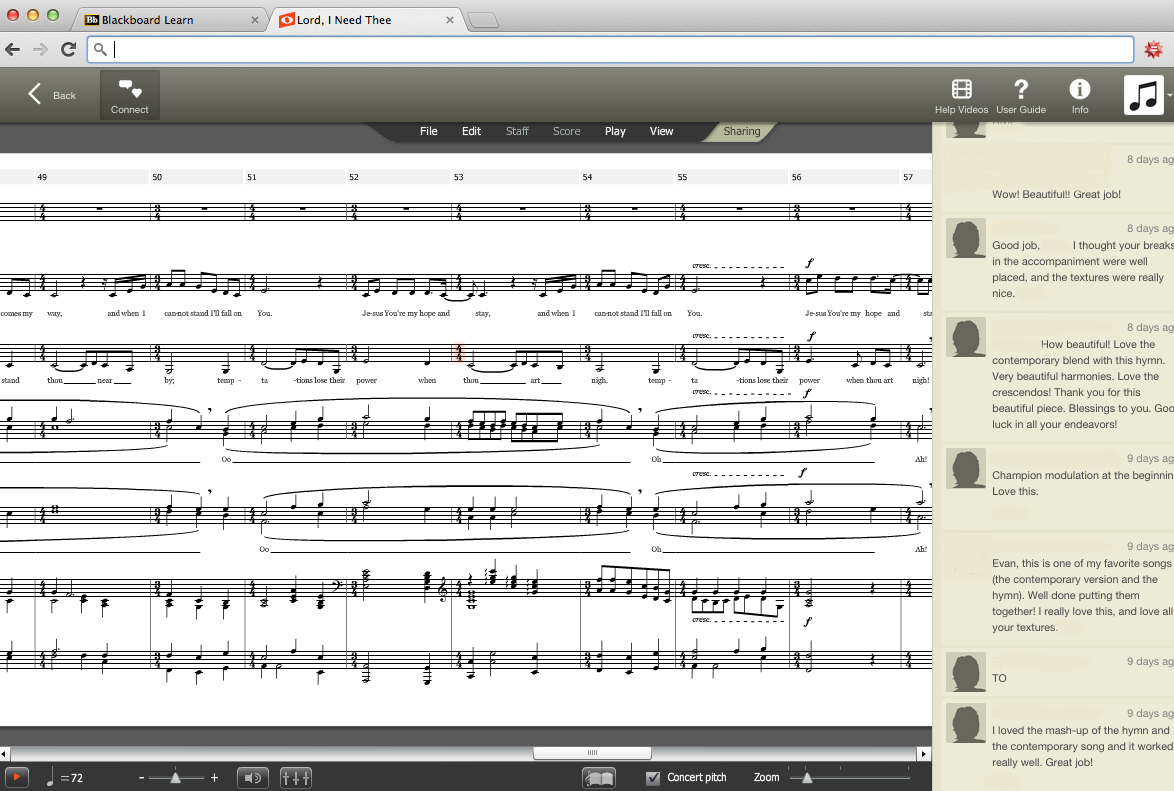

Figure 5: Example of a MUTH 450 student sharing, and receiving comments on, their final arrangement. Used by kind permission from the student.

Figure 6: Example of a MUTH 450 student reflecting in their first paragraph and reimagining in the second paragraph of their Blackboard blog. Used by kind permission from the student.

Findings

Quantitative Findings

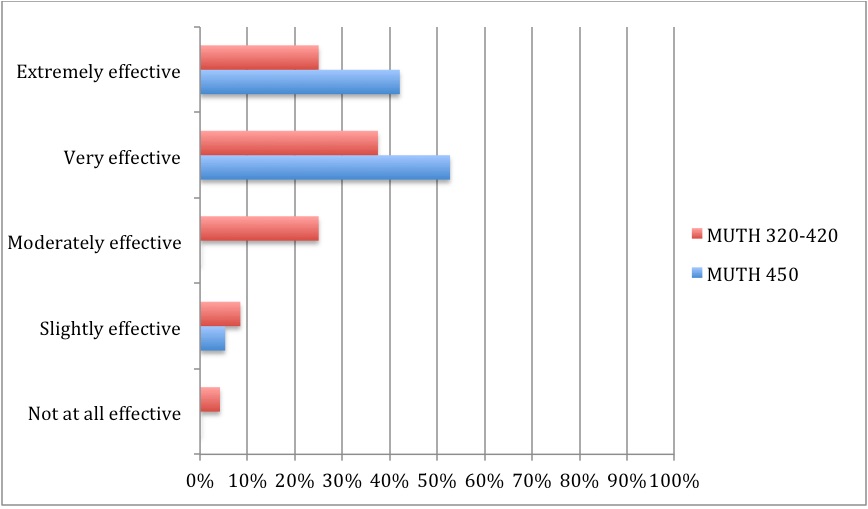

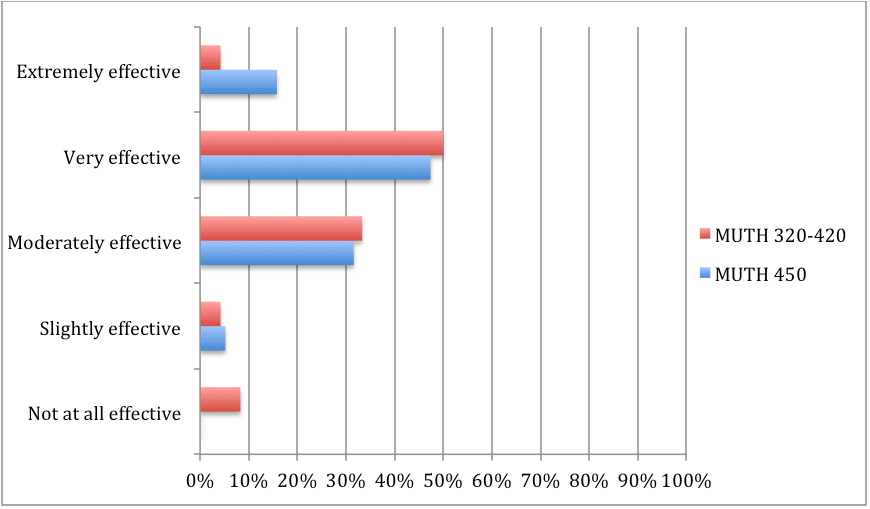

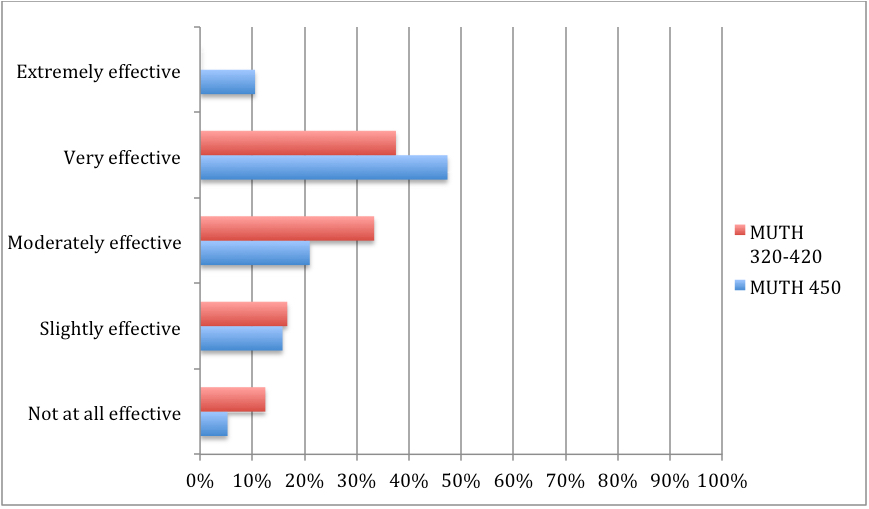

The questionnaires asked the students the primary research questions in this study. First, regarding the initial question, 63% of MUTH 320-420 students and 95% of MUTH 450 students felt that the Lifelong Kindergarten (spiral) model was “very” or “extremely” effective in stimulating creative learning experiences in their arranging course (see Figure 7). Second, the feedback showed that 54% of MUTH 320-420 and 63% of MUTH 450 students felt Noteflight was “very” or “extremely” effective in enabling the Lifelong Kindergarten to be present in the course (see Figure 8). Most of the remaining students in both of these classes felt that it was “moderately” effective in allowing Lifelong Kindergarten. Furthermore, 38% of MUTH 320-420 students and 58% of MUTH 450 students felt that blogs were also “very” or “extremely” effective in enabling the spiral to be present in the course (see Figure 9).

Figure 7: MUTH 320-420 and MUTH 450; “Was the Lifelong Kindergarten approach (spiral) effective in stimulating creative learning experiences in this arranging course?”

Figure 8: MUTH 320-420 and MUTH 450; “How effective was Noteflight in enabling the spiral to be present in our course this semester?”

Figure 9: MUTH 320-420 and MUTH 450; “How effective was blogging in enabling the spiral to be present in our course this semester?”

The questionnaires also solicited qualitative feedback through open-ended questions. The following sub-headings and student responses represent trends in the qualitative data.

The Course Modeled the Spiral; Perhaps More Time for Cycle Needed

• Most MUTH 320-420 students felt the course successfully modeled the spiral with a short explanation. For instance, one student reported, “I think it was definitely very close to this model. I can see where each part pertains to the process used in arranging. I think the steps are somewhat interchangeable as well.” Another student reported: “Yes, this method allowed working independently and really learning the subject matter through practice rather than just lecture.”

• Several MUTH 320-420 students found that it worked to a degree but they had some complaints. For instance, one student found the process effective but “crammed,” while another thought that after finishing the arrangement the blog was “less useful.”

• Nearly all MUTH 450 thought their course successfully modeled the spiral and many added short explanations. For example, one student responded, “Yes, we were able to share and reflect on what worked and what didn’t then go back and make any changes that were noticed in sharing.” Another student wrote, “I think that the amount of imagining/creating (arranging) done in this class was extremely beneficial for everyone.”

• MUTH 450 students only complained about the pace and the length of time given to complete the assignments. One replied, “I am a big fan of the spiral in learning. I would have liked more time to read over arrangements and give/receive feedback.”

Tools for Spiral: Noteflight Effective, Blogs Less So

Students were also asked to provide feedback regarding the specific technologies and their facilitation of components of the spiral.

Regarding Noteflight and creating:

• MUTH 320-420 student: “It helps us exceed our initial visions.”

• MUTH 450 student: “Noteflight definitely helped the creation process because it’s much easier to flesh out ideas using the technology than hand writing.”

Regarding Noteflight and playing:

• MUTH 320-420 student: “It really helped me play with my music. Although I would probably use a more high-powered software for more complicated works.”

• MUTH 450 student: “I think Noteflight was just fine in playing with my ideas. It kept up with whatever I wanted to do. It has a quirk or two, but it is alas technology.”

Regarding Noteflight and sharing:

• MUTH 320-420 student: “Being able to share arrangements in Noteflight was extremely helpful in the learning process. I enjoyed seeing what other students were creating, and their ideas helped to stimulate my own on later projects.”

• MUTH 450 student: “Sharing arrangements was scary at first because I was always ashamed with what I had composed but hearing some good things about my arrangements made me feel better about my decisions.”

• MUTH 450 student: “It motivates the student in the arranging learning process, because there is an expectation that someone will not only be listening, but commenting on your arrangement.”

Regarding blogging and reflecting:

• MUTH 320-420 student: “Using the blogs didn’t really help me reflect, I think this was because physically documenting my reflection seems silly to me. I tend to reflect better on my own without the necessity of a blog.”

• MUTH 450 student: “In reflecting you start comparing yourself to what others have done, therefore you can be motivated to try new things, or, be discouraged from stepping outside your comfort zone.”

Regarding blogging and reimagining:

• MUTH 320-420 student: “I’m not sure that it helps or hinders. Imagining what the music will sound like is kind of an individualized experience and ability.”

• MUTH 450 student: “Blogs helped quite a bit, since it gave us a place to jot ideas down for next time after listening to other arrangements.”

Discussion

This project provided meaningful experiences for both the students and for myself, as the instructor. It also offered evidence that students can respond well to formally integrating Resnick’s “creative thinking spiral” into their college music-arranging course. Questionnaire feedback, combined with my reflections on the classes, provides several notable findings.

First, I have taught both orchestration and choral arranging courses several times prior to the semesters involved in this study, and I strongly feel the overall quality of the arrangements in these two course sections was higher than in previous semesters, particularly with regard to scoring and creativity. Scores were generally more polished and clearly notated in these sections of the course when compared to previous semesters. This may have occurred because the students knew that all of their classmates, not just the instructor, would be examining and evaluating their scores at the conclusion of assignments. Peer assessment seemed to play a critical role in score improvement. In addition, though difficult to quantify, arrangements seemed to experiment with a greater variety of colors and textures than in their counterparts from previous semesters. My arranging courses have used notation software in the past but never in a formalized model that emphasized sharing and reflection. Not coincidentally, the level of communication regarding each other’s scores increased during these two course sections when compared to past sections. This increase in communication resulted from expanding the in-class discussion forum to blogs and the Noteflight comments section. As such, I believe that stronger arrangements resulted from increased peer evaluation, sonic experimentation in Noteflight, and student communication.

Second, the model and its tools all seemed to be perceived as more effective from the slightly more advanced course, or MUTH 450. MUTH 320-420 was made up of 23 undergraduates and only one graduate student (4% of class); 9 of the 23 undergraduates (39%) were in at least their fourth year as a music student. In contrast, MUTH 450 included 13 undergraduates and six graduate students (32% of class); 7 of the undergraduates (54%) were in at least their fourth year as a music student. Not only was there a much higher percentage of graduate students in MUTH 450, there was a higher percentage of students who had already completed at least three years of undergraduate music training. So why were the spiral model, Noteflight, and blogging all perceived as more effective in MUTH 450? One might predict less advanced students would benefit more from sharing ideas with their peers within the model and software, perceiving it as more effective. However, I believe the slightly more advanced students were better prepared to carry out all components of the spiral, thus perceiving greater benefits. Not only did they potentially feel more comfortable working in the open-ended portions of the spiral (i.e. imagine, create, play, reimagine) in Noteflight, they may also have been more at ease in the sharing and reflection sections of the spiral in Noteflight and blogging. In general, music theory students in their sophomore and junior years often experience a transition in their assessments, from learning the tools of theory, analysis, and arranging to putting them to work through critical thinking. Theory assessments during these years become less focused on description and more on analysis.31 The MUTH 450 students, having largely already passed these transitional years, may have been better prepared to apply critical thinking in all parts of the spiral. Even if it was their first arranging course, the MUTH 450 students may have had more experience in analyzing source material, deconstructing their designs, and reconsidering their settings within larger ensembles. They may have also been more confident in sharing their ideas with others as well as appreciating contrasting perspectives. Therefore, the findings could suggest that the model might be perceived as more effective in more advanced courses.

Third, though Noteflight proved itself as an overall asset to the model and the course, several students in each course who had previous experience with desktop notation editors became periodically frustrated with the software. Students normally used their personal computers to connect on campus or at home to the web-based notation software Noteflight. No students reported web connection issues. All students used the point-and-click method of note entry.32 After analyzing their feedback, I believe this group of students’ frustrations is summarized well in one comment from the MUTH 450 course that reported, “I made unusual markings in nearly all of my assignments in order to get a satisfactory result from the playback. In another program such as Finale, the score might look more natural while still producing a pleasing result.” The small group of students experienced in using desktop notation software felt Noteflight lacked certain playback and engraving options for their arrangements. For these students, improving the MIDI sounds gave rise to the unfortunate additional step of unconventionally marking their scores, even if only temporarily. As I became aware of this sporadic practice I continually reminded the students to proofread their scores before final submission to ensure all strange markings were removed. As mentioned, I knew the notation options were more limited when I chose Noteflight to facilitate the spiral. However, I felt that the small learning curve of Noteflight and the powerful sharing functionality added unique value to the software in a manner unmatched by other notation editors. I believe instructors must weigh the value of score sharing (advantage: Noteflight) against the value of professional scoring and playback options (advantage: Sibelius or Finale). Noteflight Crescendo’s HTML 5 editor is a good option for creating scores, though it is not yet ideal for professional scoring. If Noteflight is used, instructors should remind students experienced in using other notation software to proofread their scores before final submission.

In certain respects, the study’s findings regarding specific technologies are congruent with past studies reporting on their uses in music courses. Eddy Chong has published several articles on the importance of blogging in music courses, and specifically on its ability to enable students to engage in peer discussion and evaluation. He has encouraged a classroom “to see themselves as members of a community of learners, in which individuals have differing levels of expertise, but are collectively engaged in learning.”33 Chong has also noted that he has modified his course content based on blogging experiences in his classes.34 The present study indeed illustrated this community of learners, and I envision that my arranging courses will continue to expand the nature of score sharing and online discussion; better arrangements and positive feedback from students have prompted this new trajectory. Other scholars have studied the use of Noteflight and have found similar positive impacts regarding peer assessment and group learning. Alex Ruthmann and Steve Dillon have reported on a middle and high school teacher who divided his students into groups and had them use Noteflight when composing music inspired by a piece of visual art. In their report, Ruthmann and Dillon state: “As the composing task was organized as a group experience, the less experienced students learned from the more experienced, and all were able to make a contribution to the end product.”35 Though that study dealt with younger students, it also observed the software’s ability to facilitate collaboration and group learning. Finally, my previous work in a 2011 case study showed a finding somewhat consistent with the present study, namely that more advanced students may be better equipped to reap the benefits of Noteflight score sharing and theory class collaboration (though not specifically arranging).36 The 2011 study had students in both an undergraduate music theory course (Theory III) and a graduate music theory pedagogy course complete writing and analysis projects in Noteflight and then share their scores with their class in a closed, UTK environment. Part of the feedback in a concluding questionnaire asked all students to select the level of their agreement with the statement, “I recommend the use of Noteflight as a notational and collaborative application for the music theory sequence.” The mean response rate on a five-point Likert scale (from strongly agree–strongly disagree) for the graduate course was 4.19 (N = 19; Std. Dev. 1.12) while the undergraduate course was 3.54 (N = 13; Std. Dev. 1.05). In that small study, it is also possible the graduate students perceived more benefits from Noteflight and as such they provided a higher level of recommendation for its collaborative use in theory classes.

In conclusion, this study proved successful though there is room for re-evaluation of the methodology. Many students in MUTH 320-420 and most in MUTH 450 reported that they found the design effective in stimulating creative learning experiences in their course. In general, both instructor and students found Noteflight successfully enabled aspects of the model to be present, most notably in playing with and sharing scores. Blogging also seemed to work well in the spiral, though perhaps not as successfully as Noteflight. The implementation of the spiral could perhaps be improved in a few ways. For instance, the experience might be a bit stronger if students were given more time to complete each project and even carry out at least two complete cycles of the spiral. In this case, each course would need to trim the number of total arranging projects. The spiral model might also be improved through other technologies, notably in the reflection and reimaging steps. Yet overall, the project proved to be very worthwhile and certainly merits continued exploration.

Bibliography

Adler, Samuel. Workbook for the Study of Orchestration. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.

Anderson, Chris. "20 Years of Wired: Maker Movement." Wired. May 2, 2013. http://www.wired.co.uk/magazine/archive/2013/06/feature-20-years-of-wired/maker-movement.

_______. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business, 2012.

Chong, Eddy K.M. “Blogging Transforming Music Learning and Teaching: Reflections of a Teacher-researcher." Journal of Music, Technology & Education 3, no. 2-3 (2011): 167-82.

_______. "Teaching Music Theory Using Blogging: Embracing the World of Web 2.0." 2008 CEPROM Proceedings. 17th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), International Society for Music Education (ISME), Spilamberto, Italy. http://issuu.com/official_isme/docs/2008-ceprom proceedings?viewMode=magazine&mode=embed

Golinkoff, Roberta, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, and Dorothy Singer. "Why Play = Learning: A Challenge for Parents and Educators." In Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children's Cognitive and Social-Emotional Growth, edited by Dorothy Singer, Roberta Golinkoff, and Kathy Hirsh-Pasek. New York: Oxford, 2006.

Harel, Idit, and Seymour Papert. "Situating Constructionism." In Constructionism, edited by Idit Harel and Seymour Papert, 1-13. Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1991. http://www.papert.org/articles/SituatingConstructionism.html.

Honey, Margaret, and David Kanter. Design, Make, Play: Growing the next Generation of STEM Innovators. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013.

McConville, Brendan. “Noteflight as a Web 2.0 Tool for Music Theory Pedagogy.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 26: 265 – 289.

Piaget, Jean. Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. New York: Norton, 1962.

Resnick, Mitchel. "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten." Presented at Creativity & Cognition Conference, Washington, 2007. http://web.media.mit.edu/~mres/papers/kindergarten-learning-approach.pdf.

_______. "Falling in Love with Seymour's Ideas." Presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, New York, 2008. https://llk.media.mit.edu/papers/AERA-seymour-final.pdf.

_______. "Kindergarten Is the Model for Lifelong Learning." Edutopia. May 27, 2009. http://www.edutopia.org/kindergarten-creativity-collaboration-lifelong-learning.

_______. "Sowing the Seeds for a More Creative Society." Presented at EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology, Victoria, 2013. http://web.media.mit.edu/~mres/papers/Learning-Leading-final.pdf.

Resnick, Mitchel, and Eric Rosenbaum. "Designing for Tinkerability." In Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators, edited by Margaret Honey and David Kanter, 163-81. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013.

Rogers, Michael R. Teaching Approaches in Music Theory: an Overview of Pedagogical Philosophies. Second ed. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Ruthmann, Alex, and Steven Dillon. "Technology in the Lives and Schools of Adolescents." In The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Volume 1, edited by Gary McPherson and Graham Welch, 529-547. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Notes

1Resnick, "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten," 2.

2Ibid, 1.

3“The MIT Media Lab at a Glance.” http://www.media.mit.edu/files/overview.pdf

4Resnick, “Kindergarten is the Model for Lifelong Learning,” para. 10.

5Resnick, “Falling in Love with Seymour’s Ideas,” 1. Regarding constructionism, Papert writes: “Constructionism--the N word as opposed to the V word--shares constructivism's connotation of learning as ‘building knowledge structures’ irrespective of the circumstances of the learning. It then adds the idea that this happens especially felicitously in a context where the learner is consciously engaged in constructing a public entity, whether it's a sand castle on the beach or a theory of the universe.” (Papert and Harel, 1991, 2)

6Resnick, "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten," 3.

7Resnick, “Kindergarten is the Model for Lifelong Learning,” para. 2.

8Resnick, "Sowing the Seeds for a More Creative Society," 1.

9Resnick, "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten," 1.

10Ibid, 2.

11Resnick, “Kindergarten is the Model for Lifelong Learning,” para. 5.

12Resnick, "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten," 3. Also see: Piaget, Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood.

13Resnick and Rosenbaum, "Designing for Tinkerability," 164.

14Ibid, 164.

15Honey and Kanter, Design, Make, Play, 1.

16Ibid, 2.

17Anderson, Makers: the New Industrial Revolution, 8.

18Anderson, “20 Years of Wired: Maker Movement,” para. 2.

19Ibid.

20Resnick and Rosenbaum, "Designing for Tinkerability," 163.

21Golinkoff, Hirsh-Pasek, and Singer, “Why Play = Learning: A Challenge for Parents and Educators,” 10.

22At UTK, MUTH 320 Instrumentation (2 credits) is taken by a variety of students and populated largely by music education students. It covers fundamental concepts such as transpositions, scoring techniques, etc., but it also includes four arranging projects for various forces. Instrumentation only meets during the first eight weeks of the semester. MUTH 420 Orchestration (3 credits) meets jointly with MUTH 320 and is comprised of primarily composers and theorists. After eight weeks the MUTH 320 students are finished with the class and the MUTH 420 students continue on to topics such as history of orchestration, scoring for large ensembles, etc. This research studied the spiral’s impact during the joint eight-week session of MUTH 320 and MUTH 420, only.

23The study occurred after gaining approval from the University of Tennessee’s Institutional Review Board. The Board determined the study complied with proper consideration of the rights and welfare of human subjects.

24For more information on Noteflight Campus see: https://www.noteflight.com/info#/highered.

25For more information on Blackboard course-management software and recent service packs see: http://www.blackboard.com/.

26Resnick and Rosenbaum, "Designing for Tinkerability," 166, 176-179.

27Resnick, "All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten," 5.

28MUTH 320-420 used and pulled all arrangement source material from the textbook Workbook for the Study of Orchestration by Samuel Adler. MUTH 450 used and drew some of its source material from Contemporary Choral Arranging by Arthur E. Ostrander.

29Resnick, “Falling in Love with Seymour’s Ideas,” 1.

30For more information on SurveyMonkey and plans see: https://www.surveymonkey.com/.

31In the area of music theory and analysis this concept is described in Rogers, Teaching Approaches in Music Theory: an Overview of Pedagogical Philosophies, 76.

32Though students in this study used point-and-click entry, a Noteflight MIDI Adapter application is available for note entry from MIDI controllers. See: http://midi.noteflight.com/

33Chong, "Teaching Music Theory Using Blogging: Embracing the World of Web 2.0," 28.

34Chong, Blogging Transforming Music Learning and Teaching: Reflections of a Teacher-researcher,” 176.

35Ruthmann and Dillon, “Technology in the Lives and Schools of Adolescents,” 540.

36McConville, “Noteflight as a Web 2.0 Tool for Music Theory Pedagogy,” 283-84.