Abstract

William Grant Still’s Seven Traceries (1940) is a set of piano pieces that exhibits a number of post-tonal materials and techniques such as octatonicism, extended tertian sonorities, dense chromaticism, and extensive motivic development. Still’s concentration on these more contemporary features marks definite contrasts from the more conservative character of his acclaimed, and perhaps better-known, nationalist compositions from the early 1930s. Studies of post-tonal music in theory and history courses would benefit from an expansion of repertoire, and the Traceries provide solid examples of the aforementioned materials and techniques as well as extensions to our pedagogy and teaching pieces by way of a diverse voice in Western concert music. This essay draws attention to the pedagogical potential of two of the Traceries (“Woven Silver” and “Out of the Silence”) and extends discourses on Still into non-black-nationalist compositions. Through general orientations and examinations of structural details, I demonstrate the applicability of the two selected Traceries for music theory or history courses.

Almost twenty years ago, Lucius Wyatt noted a “notorious deficiency” in the treatment of concert music by African-American composers in general music histories.1 There have been some advances since the time of his call for more inclusion.2 William Grant Still (1889-1978) has received a fair amount of scholarly attention since Wyatt’s call. In addition, he is the African-American composer most frequently mentioned in music history and appreciation textbooks. Often heralded as the “Dean of Afro-American composers,” Still was as prolific as he was pioneering.3 He composed over 150 works for various performance forces over the course of his long and distinguished career, but he is perhaps best known for the acclaimed Afro-American Symphony (1931). The symphony was lauded for its blend of blues and Western European elements. While significant and deserving of continued study, the Afro-American and other black-nationalist works composed around that time constitute only a portion of his output.4 There was much more music written after the Afro-American, and various styles, techniques, and influences appear in works composed from 1935 onward. The Seven Traceries (1940) is a set of piano pieces that demonstrates this variety, as they include modern styles and techniques, and black vernacular emblems, if at all present, are subtly engaged. The following commentaries on William Grant Still and the Seven Traceries serve a two-fold purpose: (1) to draw attention to the potential of the Seven Traceries in pedagogical and performance settings and (2) to further extend discourses on the composer into non-black-nationalist compositions.5 Furthermore, this study seeks to broaden pedagogical perspectives of the composer by examining structural details in “Woven Silver” and “Out of the Silence” from the Seven Traceries—short pieces which utilize post-tonal materials and techniques that could be incorporated in music theory classes, music history classes, or both. Whereas Wyatt’s inclusionary call focused on traditional music history courses, the implications also reach into music theory courses.

Studies of post-tonal techniques and materials in music theory and history courses might benefit from an expansion of repertoire that employs dense chromaticism, extensive motivic development, octatonic and hybrid scales, “tall” chords (e.g., ninth and/or thirteenth chords), and so forth. Indeed, the inclusion of Still’s “Woven Silver” in the Kostka/Graybill anthology is encouraging.6 Their reading of “impressionist” influences places the piece in a modernist context and welcomes differing perspectives and methods of analysis.7 In addition to providing solid examples of the aforementioned techniques and materials associated with post-tonal music, the Traceries afford extensions to our pedagogy and teaching pieces by way of a diverse voice in Western concert music. The individual pieces are also small enough to where coverage, over a short period of time, could afford opportunities for students to explore formal schemes and relationships between harmonies, motives, or both that contribute to global unity. Such explorations would enhance the sometimes taxonomic outcomes that surveys of various contemporary techniques yield and expand musical contexts beyond the excerpt. Following the next section that provides additional contexts and orientation, I offer overviews and analytical notes on two pieces from the collection, “Woven Silver” and “Out of the Silence.” The analytical notes are generally presented in a “left-to-right” fashion, suggestive of an approach that may be used to discuss the entire piece from beginning to end—with occasional moments of added emphasis on details of local and global significance.

Context and Orientation

In the Introduction to the William Grant Still Reader, Jon Michael Spencer identifies three stylistic periods for the composer’s works. Spencer’s first two periods cover a twelve-year period (1923-1934) highlighted by the composer’s study with Edgard Varesé (a French avant- garde composer) and a deliberate turn toward the use of black cultural subjects in his compositions. The third period, from 1935 to the mid-1970s, is one defined by “stylistic eclecticism.”8 Still referred to this latter period as one that favored a “universal idiom” where “instead of limiting [him]self to one particular style, [he] wrote as [he] chose, using whatever idiom seemed appropriate to the subject at hand.”9 He incorporated many styles and references in his works during this period, including black cultural themes (African, African-American, and Afro-Caribbean subjects), Mexican folk song, and the modern influences of Varesé. He began writing original music for piano in 1935 and the body of solo works similarly shows a variety of styles and influences.10 These range from folk-like, pentatonic themes in “Quit Dat Fool’nish” (1935) to extended tertian complexes that characterize “Phantom Chapel” from the Bells (1940).

Carolyn Quin identified three categories for Still’s piano works: (1) mystic/academic, (2) Afro-American, and (3) neo-romantic film music style. Quin’s “neo-romantic” category is designated for pieces that display “impressionistic parallel chords and floating rhythms.”11 Most of Still’s solo piano music falls under the mystic/academic and neo-romantic categories. The mystic label is based on the composer’s growing interest in spirituality and the interpretation of dreams and visions during the post-nationalist phase of his career. Titles such as “Radiant Pinnacle” and “Cloud Cradles” are considered representative of that particular facet of Still’s inspiration.12 The academic designation is related to Still’s freer use of dissonance and the incorporation of more contemporary materials such as polychords and octatonic scales. The mystic/academic works are somewhat similar to pieces composed during Still’s early period because they reflect modernist influences that affected Still during his years of study with Varesé. Still referred to his early works as “ultramodern,” as he was probably encouraged to eschew conventional approaches and to experiment with different harmonies, timbres, and effects.13 Many of the works were more demonstrative of his instructor’s influence than his own compositional voice. In an essay, entitled “A Composer’s Viewpoint,” Still recalled the encounter with ultramodernism:

… for me, the so-called avant-garde is now the rear guard, for I studied with its high priest, Edgar Varesé, in the 20s, and I was a devoted disciple. Some of my early compositions in that idiom were auspiciously performed in New York. … I learned a great deal from the avant-garde idiom and from Mr. Varesé but, just as with jazz, I did not bow to its complete domination.”14

The time Still spent with Varesé was certainly meaningful, as he reflected on his teacher opening “new horizons” and avant-garde influences “loosen[ing] up his music” in interviews recorded as late as 1969.15

Considering the influence of Varesé and the number of Still’s piano works which utilize contemporary techniques and styles associated with French impressionist composers, were there any connections between Still and impressionist composers such as Claude Debussy or Maurice Ravel? While I have found no mention of Debussy in connection with the Still’s two years of study with Varesé, he may have become familiar with the works of impressionist composers through the concert programming and lessons of his teacher. Debussy was a significant figure quite early in Varesé’s musical life and they maintained a friendship for a number of years.16 Varesé founded the International Composer’s Guild in 1921 and Ravel was among the composers for whom the Guild programmed world or American premieres.17 The Guild was active through the 1920s and programmed some of Still’s works as well. It is reasonable to assume that score study was a part of Varese’s pedagogy and that Debussy and Ravel may have been among the composers Still studied. Still was also a conductor and arranger for a New York-based radio orchestra in the early 1930s, referring to his work with the Deep River Broadcast as “the most remarkable opportunity I’d ever had.” Not only did he have “splendid musicians” play his arrangements, the orchestra “played all sorts of things, Debussy and things of that sort.”18 Furthermore, Still named Debussy and Ravel as European composers who incorporated black-folk elements in compositions in at least three different articles written between 1944 and 1950.19

Connections to the French composers notwithstanding, there are musical features in the Traceries that exhibit contemporary styles and techniques. Tertian chords are the harmonies of choice in most of the pieces; chromatic extensions and added notes are sometimes employed. Some of the harmonic dissonances also result from chords that are derived from non-conventional scale types (e.g., octatonic and hybrid scales). Each of the Traceries is in ternary form and prominent ideas are sometimes combined at or near the end of the pieces, contributing additional unifying elements. Quin describes the formal processes in “Cloud Cradles” as “organic, i.e., growing out of the motive,” and this is certainly the case in four more of the Traceries: “Muted Laughter,” “Woven Silver,” “Wailing Dawn,” and “A Bit of Wit.” The other two pieces, “Out of the Silence” and “Mystic Pool,” are based on longer melodic ideas.20 In all of the pieces, however, motives and melodic fragments recur frequently, often with some form of variation (e.g., altered contours, transposition, etc.). Harmonic treatments involve root relationships by second, third, and tritone, and there are also a few instances of functional harmonic activity on local and global levels. Still’s concentration on the aforementioned features in the Seven Traceries marks definite contrasts from the more conservative character of Still’s black-nationalist compositions from the early 1930s. Verna Arvey noted in 1940:

It is significant that many of his compositions for piano solo are couched in a style different from the majority of his orchestral works. Many of them are almost completely lacking that deep racial quality that characterizes much of his music. The Seven Traceries are abstractions bearing the imprint of mysticism, yet none of their dissonance is illogical: everything blends harmoniously into the whole. Each has a delicacy of a rare print. … Each is based on the simplest of motifs, developed to the extent of its own possibilities.21

Pianist Richard Crosby agrees with Arvey regarding inspiration and interpretation and also observes “exquisite craftsmanship” in the composer’s treatment of motive. Whereas “Still did not rely on his inspiration only,” the works demonstrate “a great skill of proportion and balance.”22

“Woven Silver”

Overview

“Woven Silver,” as noted earlier, is included in the Kostka/Graybill anthology where the Seven Traceries are considered “somewhat impressionistic in style, with few instances of the African-American elements that can be heard in some of his music.”23 With the exception of a few minor major seventh chords that may evoke a jazz presence or transitory, understated pitch inflections that might signal shadings of blue, the vernacular emblems in “Woven Silver” are, at best, trace in appearance. Among the devices and techniques identified “Woven Silver” are hybrid (synthetic) scales (mm. 39—48), octatonic scales (mm. 23—36), polytonal episode (mm. 1—8), and establishing pitch centricity by pitch assertion and gesture.

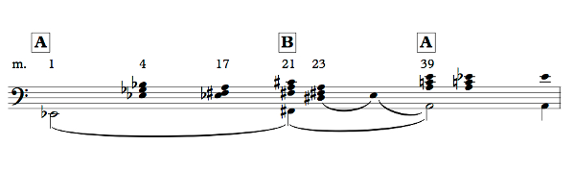

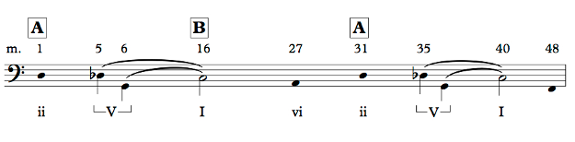

There are other linear and horizontal constructs based on manipulations of major, augmented, and diminished triads. The main sections of the ternary form are articulated by statements and varied restatements of the primary motives in the outer sections (mm. 1—20 and 37—48) and a contrasting section (mm. 21—36) that consists of developmental episodes. Contrast is also facilitated by a marked arrival at new tonal center that is confirmed by a particular gesture (the P5/P4 figure) discussed below. A sketch showing the formal functions of the structural pitches appears in Figure 1. The structural pitches, Eb, F#, and A, are supported with minor triads. Also note the diminished triads that frame the F# minor chord. This is particularly relevant because these triads are comprised of the structural pitch classes and the chords function globally to move the piece into and out of the contrasting section. The F# from the diminished sonority in measure 17 creates a relatively smooth common-tone modulation to the F# minor tonal area in measure 21. The D# diminished chord that occurs after the F# minor arrival tonicizes the pitch (E-natural) that ultimately prepares the arrival of A minor in the final A section. These features are likely to surface in discussions about harmonic details, and drawing attention to these particular treatments of the diminished sonority may prompt students to consider other factors that contribute to the global unity within “Woven Silver.” The final sonorities in the sketch show some play between Eb and E-natural at the conclusion of the piece. A discussion of this feature will be included with the discussion of motive.

Figure 1. Bass sketch and form diagram, “Woven Silver.”

Analytical Notes

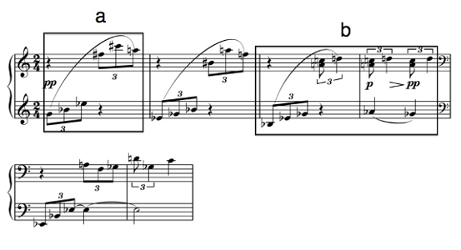

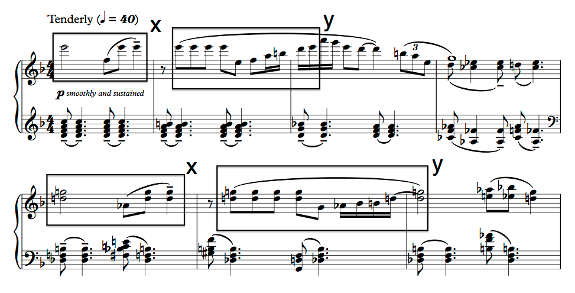

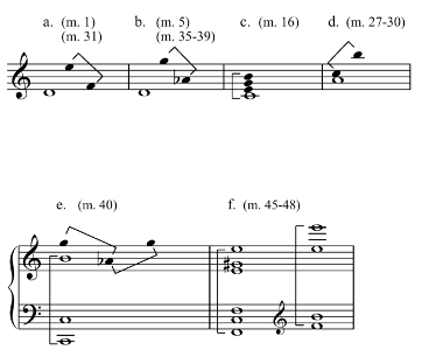

Perpetual triplet motion and two primary motives constitute much of the piece’s content. See Figure 2 (mm. 1-6). The motives are introduced at the beginning of the piece and are labeled a and b. Sometimes fragmented or treated with changes in the intervallic content of the leaps, these motives appear in some form in each of the piece’s main sections and transitional sections. Note the ascending perfect fifth/perfect fourth (P5/P4) figure in measure 5. This figure is significant because it aids in establishing Eb as a pitch center. Considering Still’s opening statements that suggest a polytonal treatment of D (in the right hand) and Eb (in the left), this relatively consonant gesture provides contrast and also aids in articulating the pitch center for this section. It is important to note here that there are only three occurrences of the ascending P5/P4 figures in “Woven Silver.” Each assists in confirming the pitch centers (Eb, F#, and A) and articulating formal structure. The figure in measure 5 and its repetition in measure 7 provide a strong confirmation of Eb as a pitch center at the beginning of the piece, although the right hand figures suggest a subsidiary presence of D. In addition, Eb is asserted through its longer duration in the local context of the initial P5/P4 figures. See Figure 1 again. When the figure appears in measure 21, it confirms F# minor by having all members of the triad present. Its statement in opening measures of the final A section (m. 39) suggest A minor, but the minor triad is somewhat destabilized by the Eb. Still’s treatment of rhythm with the P5/P4 gesture is also noteworthy, as the duration of the emphasized pitch after the P5/P4 gesture decreases over the course of the piece—from 1 and ½ beats in measure 7 to less than one beat at measure 39. Still believed that “recurrence brings a well-defined unity” but did not “believe in exact repetitions” as he worked to avoid monotony in treatments of form, theme, and motive.24

Figure 2. “Woven Silver,” mm. 1-6, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

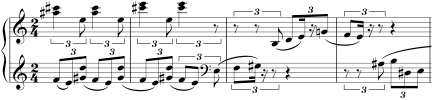

Although a number of the chromatic passages in “Woven Silver” can be attributed to imaginative uses of tertian harmonies, Still also utilizes octatonic scales in transitional and contrasting sections. Two octatonic scales are employed in the B section and in the transitional passage that prepares the final A section (mm. 23-36). Similar uses of octatonicism occur in “Out of the Silence,” which will be discussed later. Referring to Figure 3. The B section begins with brief statements of figures that outline F# minor harmony and an immediate shift to ascending arpeggios outlining a D# diminished chord in measure 23. This activity accompanies melodic fragments of motive a that are repeated and altered by subtle intervallic changes with each statement. All of the pitches in this episode (mm. 23-26), excepting a lone C# of relative brief duration in measure 26, belong to the OCT (2,3) collection.25 The C# functions as part of embedded melodic fragment based on F#, a vestige from the F# minor tonal area confirmed just before the shift to the D# diminished arpeggios. The fragment can be extracted from the second division of each right-hand triplet figure [F#, G#, B, E# (F), C#].

Figure 3. “Woven Silver,” mm. 23-26, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

An OCT (1, 2) collection is employed in measure 27, and Still uses it for the remainder of the B section as well as the transition into the final A section. The two collections share the common pitches [D, F, G#, B]. These pitches figured prominently in the development of motive a in measures 23-26, but they assume a more harmonic function in measures 27-36. The B section continues with a transposition of the accompaniment figures down a perfect fifth, yielding arpeggios that outline Ab (G#) diminished harmony (mm. 27-30). While alterations in the intervallic content within motive a continue, the G# diminished triad accompaniment is constant. E-natural becomes the predominant pitch in the transition (mm. 31-36) primarily because it is reiterated many times, but other pitches from the OCT (1,2) collection are also present and contribute to a hearing of the E as a root of a dominant preparation (E7) for the key of A. G#/D dyads are stated melodically and harmonically in close proximity to the E in measures 31-35. In addition, the melodic G-naturals and F-naturals that occur in this passage function as colorful extensions (#9 and b9, respectively) to E dominant harmony. One final detail related to the importance of E in the transition is in its final bars. In Figure 4, the rests assure abrupt articulations of the three- and four-note figures, but this does not interrupt the persistent flow of triplets. Each figure highlights E as either the first or last pitch. Also note the D# in measure 36. It is the only pitch in this episode that does not belong to the OCT (1,2) collection; however, it tonicizes E-natural just before the arrival of A minor and the final A section.

Figure 4. “Woven Silver,” mm. 33-36, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

A few additional details of Still’s treatment of motive and the pitches Eb and A can be seen in the opening measures of Figure 2 and in Figure 5 (mm. 9-10). Please see Figure 2 again, in which it shows each of the first four measures with statements of the pitches Eb and A in both of the main motivic figures. Eb is featured in the left hand figures that outline major or minor triads, and the pitch A occurs in each of the tails of motive a as well as the repeating tail of motive b. With reference to Figure 5, measures 9 and 10 mark a departure from Eb, as a new pitch center (D), is suggested by the literal transposition of the head of motive a down a minor ninth. The statements of motive a’s tail, however, feature changes in intervallic structure while maintaining certain pitches. The tails (C#-A) and (A-F) remain unchanged, though presented an octave lower than their original statements in measures 1 and 2. These tails contain the pitch A even as the composer moves away from the Eb center of the opening measures. Figure 6 shows reductions of the various transformations of motive b that occur throughout the piece. Note that the pitch A is associated with all of the statements of the motives at points that articulate harmonic structure. Motive b is subject to rhythmic displacement and large, upward leaps during the transition to the final A section at measures 33 and 34, but the treatment at measures 39-40 is significant because it involves a change in contour and also marks the arrival of final section and the pitch center, A-natural. All prior statements of motive b featured upward leaps, but the statement at measure 39 features downward leaps.

Figure 5. “Woven Silver,” mm. 9-10, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

Figure 6. Reductions of motive b, “Woven Silver.”

Still concludes “Woven Silver” with one last round of play with A and Eb. Referring to Figure 1 again, the ascending P5/P4 strongly establishes A as the pitch center in measure 39 and the C and E in the tail of motive b yield A minor as a likely key area, but there is also a D# (Eb) in the motive’s tail that somewhat trivializes the confirmation. Although the D# in measures 39 and 40 could be viewed as a chromatic neighbor to the consonant E-natural, the pitch class Eb becomes more prominent in harmonic constructs that have A as the chord root from measure 41 to measure 44. Most of the melodic figures are based on a G# fully diminished seventh chord, and it appears as though Still employs a hybrid scale collection based in A minor in these final measures. The collection used in the final A section includes natural and lowered versions of the fifth scale degree as well as both realizations of scale degree 7 [A, B, C, D, Eb, E, F, G, G#]. The last four measures offer a synthesis of the melodic and harmonic features of the final section, which includes the reworking of Eb into the local pitch scheme. This synthesis is realized linearly and vertically in the final measures. Restatements of the primary motives aid in articulating the global ternary design, and Still enhances the sense of unity in these final measures by stating the structural pitches, A and Eb (D#), in the outer voices of the piece’s penultimate chord.

“Out of the Silence”

Overview

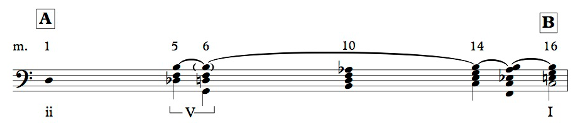

Whereas the harmonic plan for “Woven Silver” features mediant relationships between pitch centers, “Out of the Silence” has more functional tonal implications. See the large-scale ii-V-I progressions in the sketch given in Figure 7a. The highlight of this piece’s arch shape is the significant arrival in C major at the beginning of the B section (mm. 16—27). The framing A sections (mm. 1-15 and 28-48) are characterized by a four-measure thematic statement and the subsequent development of melodic fragments. The opening of the final A section is almost a literal restatement, but Still harmonizes the theme and some developmental episodes with added pitches. Colorful chord progressions complement fluid melodic lines in the B section, many of which contain mediant relationships. The B section is a good place to begin introducing the piece for a few reasons: (1) the harmonic progressions present a more “tonal” landscape than the more complex harmonies of the outer sections, (2) it is tonally closed—beginning and ending on a C major seventh chord, and (3) discussions that lead to an understanding of the local significance of CM7 can ignite inquiries into larger structural issues (e.g., How does the composer get into and out of the B section?). Figure 7b provides a sketch of the primary harmonic events that lead into the B section; discussions on these events follow. The contemporary devices and techniques in “Out of the Silence” include:

- Extended tertian sonorities (e.g., ninth chords, found throughout)

- Chromatic alterations of tertian sonorities (mm. 5-9, m. 15, and elsewhere)

- Planing/Parallelism (mm. 40-44)26

- Modal passages (mm. 1-3, mm. 18-25, mm. 30-33)

- Octatonic scales (mm. 5-13, mm. 35-39)

Notes related to these materials within the context of the piece follow as well as a synopsis on the local and global significance of the major seventh interval.

Figure 7a. Bass line sketch of primary harmonic events, “Out of the Silence.”

Figure 7b. Reduction of harmonic activity, mm. 1-16, “Out of the Silence.”

Analytical Notes

The piece begins with a leaping melodic gesture encompassing a major seventh between the pitches F and E and the first chord stated in the piece is an extended tertian harmony (Dm9) (see Figure 8). The opening gesture is accompanied with D Dorian harmonic activity in measures 1-2 and a shift to Aeolian mode in measure 3. Also note the rhythmic ostinato in the left hand. This rhythmic pattern is maintained for the better part of the first nine measures, although Still’s harmonic treatments vary. The opening thematic statement also contains melodic fragments that are developed in the A sections. They are labeled as x and y in Figure 8. Chromatic excursions and development of the melodic fragments begin immediately after the opening measures (see measures 4-7). The fragments are transposed down a minor sixth and the tail of fragment y is rhythmically altered in measure 5. There are some slight variations in the intervallic structure of the tail of fragment y, but the shape of the gesture is maintained. The chromatic excursion begins in measure 4 with extended tertian complexes that could be analyzed as inverted ninth chords. However, the primary sonority supporting most the melodic activity in measures 5 through 9 is a Db major-minor seventh chord (Db7).

Figure 8. “Out of the Silence,” mm. 1-7, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

The Db7 chord is constantly coupled with a G and D in the restatements of fragment x. Both the Db7 and melodic [G-D] dyad are pervasive because they are asserted through reiteration and they appear in the same register. Considering the arrival of C major as the main harmonic goal, the Db7 chord functions like a tritone substitution for a V chord in C—the melodic D and G could be viewed as (a flat ninth and a sharp eleventh). Tritone substitutions are considered one of the most common harmonic substitutions used by jazz musicians, and it is possible that Still may have encountered or even experimented with this particular device when he worked in popular music circuits in the late 1910s and early 1920s.27 An alternative analysis for this chord could be an inverted altered dominant (with a split fifth). Both analyses address the dominant function of the chord. Also note the oscillating chords surrounding the Db7 chord in the left hand of the piano. Whereas the upward shifts explore harmonies that have some relationship to the local pitch center of Db, the downward shifts only land on chords with G as the root. These particular harmonic features affect not only the musical surface, but also the global harmonic structure: the tritone substitute (or altered dominant) chord in tandem with the G chords functions as the structural dominant. Figure 7b shows a common tone resolution between Db7 and the C major seventh chord (CM7) that signals the beginning of the B section. This is a typical resolution for tritone substitutions.28

Octatonicism also occurs in this passage, as most of the pitch content in measures 5 through 9 belongs to the OCT (1,2) collection. Both the dominant seventh chord in C major (G7) and its tritone substitute can be generated from this collection. Exceptions to the OCT (1,2) collection are a passing Eb in an inner voice in measure 7 and two brief statements of F# and C in the oscillating accompaniment chords (measures 5 and 9). A transitional passage follows in measures 10-15 which features statements of Cb (or B) fully-diminished harmony through ascending arpeggio figures in the left hand. This activity is coupled with sprightly sixteenth note figures in the right hand that blend minor third fragments from B fully diminished and C# fully diminished chords. Thus, Still only uses pitches from the OCT (1,2) scale at the beginning of the transition (mm. 10-13). The transition assumes a foreshadowing role when a CM7 chord is briefly introduced in measure 14. Although the register is similar to treatments in the ensuing section, Still weakens the statement of the CM7 chord by preparing it with a V4/2 chord on the second half of beat 4 in measure 13 and by stating the major seventh chord in first inversion. Still then harmonizes the melodic B-natural, from the C major seventh sonority, with an altered subdominant chord (Fm7 #11) in measures 14 and 15. This altered chord anticipates some of the modal inflections that occur in the B section. By maintaining the melodic B through this passage, the composer creates a local common tone resolution to the major seventh chord at measure 16 (see Figure 7b).

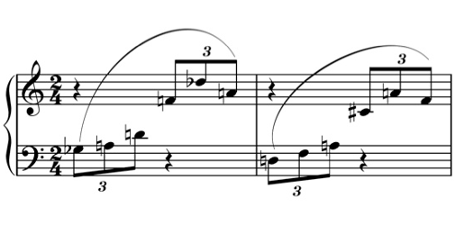

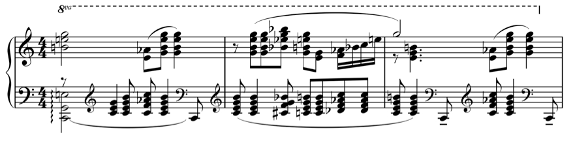

Still renders a lyrical melody supported by rolling triplet accompaniment in the B section (mm. 16-26). See Figure 9 (mm. 16—20) for a change in meter from 4/4 to 12/8 that contributes to the flowing nature of the melodic shapes and to the delineation of sectional boundaries. The major seventh sonority chord is significant in this section because the first and last of the three phrases in this section begin with CM7 chords. In addition, the final cadence in this section ends with a major seventh chord. Still also explores the harmonic possibilities of various modal infections, as hints of the Lydian and Aeolian modes appear in the melodic line in measures 18 and 19. These measures also feature a brief, chromatic excursion. Figure 9 shows that, following a statement of a minor “tonic” chord, Still progresses through a series of chords that share some mediant relationships (Cm – Abm – EM). The root of the last chord in the cycle (Db7 (b5)) is also related to the string of mediant relationships, but its function is worthy of note. It can also be analyzed as an inverted G7 chord with an altered fifth in the bass. Because this chord is leading into the beginning of another phrase that begins with a C7 chord, its dominant function is clear.

Figure 9. “Out of the Silence,” mm. 16-20, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

Following the chromatic episode, more functional progressions confirm C as a tonal center and the B section ends with a ii-V-I progression in measures 26-27. Still continues to emphasize the major seventh interval at the end of the B section, shifting to a melodic usage for the next transitional episode. He accompanies a leaping major seventh figure between the pitches C and B with sustained, ascending, arpeggio figures that outline an A minor chord (mm. 28-30). See Figure 7a again as the transitional episode prepares the arrival of final A section by way of fifth relationship (vi) to the Dm9 chord (ii) that constitutes its return. Following an almost literal restatement of the opening measures at the beginning of the final A section (mm. 31-39), Still combines the principal harmonic entity of the B section (CM7) with the primary melodic ideas of the opening A section. Referring to Figure 10 (mm. 40-42), although there are subtle variations, the melodic shapes are essentially the same as those in measures 5 through 9, and most of the accompaniment chords are major seventh chords. The composer concludes the piece with a small coda that restates the melodic fragments (x and y) with a polychordal treatment emphasizing chords built on F and E, a major seventh.

Figure 10. “Out of the Silence,” mm. 40-42, Copyright © William Grant Still Music. All rights reserved.

A synopsis of Still’s treatment of the major seventh interval is provided in Figure 11. The piece opens with a leaping major seventh gesture (m. 1) with the pitches F and E. The leaping gesture is transposed and used as the main thematic idea for a varied thematic statement (m. 5). The major seventh interval is compressed and stated in a harmonic context, with the pitches C and B, as part of the contrasting theme in the B section (m. 16). The C and B are then displaced and stated, melodically, in the transition before the restatement of the primary theme (mm. 27-30). The restatement is ornamented with added pitches, but the melodic major seventh [F-E] is still intact (m. 31). The melodic seventh continues to dominate the literal restatement of the A section theme in mm. 35-39 [Figure 11 letters e and f]. Here the final statement of C tonality combines the melodic seventh (Ab-G) from the A section with the harmonic seventh (C-B) from the B section theme. Still concludes the piece by harmonizing the pitches from the initial introductory passage (F-E), stating E major triads with a heavy emphasis on F in the bass voice. The piece ends with an ascending figure based on the F/E polychord, and concludes with a sonority where F and E sound almost simultaneously and are the lowest and highest pitches respectively. Still’s treatment of the major seventh affects the melodic, harmonic, and formal structures in “Out of the Silence.” Although he offers rather disparate themes for the contrasting A and B sections, the manipulations of the horizontal and vertical realizations of the major seventh contributes to the global unity of the work.

Figure 11. Synopsis of treatments of the interval of a seventh, “Out of the Silence.”

Conclusion

Through general overviews and examinations of structural details in two of the Seven Traceries, this essay sought to demonstrate the potential of the pieces for study in the music theory classroom (or period-specific courses devoted to musical developments in the twentieth century). Certain excerpts from the Traceries would provide good examples of post-tonal techniques and materials such as extended tertian harmony and octatonic collections, but the added instructional benefits are in the brevity of the pieces and in Still’s use of ternary form. Although Still explores sonorities and ideas more with modern styles, the broader formal principle of “statement-contrast-restatement” can be applied effectively to the two pieces covered in this essay and to the other Traceries as well. An overarching impressionist quality is evoked in all of the Traceries, and the formal and harmonic schemes in “Out of the Silence” and “Woven Silver” suggests that the composer relied on conventional formulae as well. Chromatic mediant relationships are shared between the three primary pitch centers in “Woven Silver” and Still uses a specific motive to emphasize those points of centricity. A global ii-V-I progression governs “Out of the Silence,” but tertian complexes such as tritone substitution (or altered dominant) chords affect local and large-scale structures. Octatonic scales are used in both pieces during transitional episodes, but sometimes pitches are given more structural weight for the purpose of creating functional harmonic relationships. The extent of motivic development encountered in the pieces ranges from virtual saturation and perpetual play in “Woven Silver” to confirming agents of formal processes in “Out of the Silence.”

In complement to music theory exercises that involve identifying the particular post-tonal materials (scales, chords, etc.) mentioned, discussions on the Seven Traceries can be extended to inquiries about how Still avoids monotony within ternary forms. In such discussions, harmony, motivic development, and texture are all possible points for engagement. For more historical or cultural studies that involve African-American music and musicians, the Seven Traceries and similar piano works by Still can offer a platform for discourses on artists who did not always actively engage vernacular emblems in their works. The modernist affinities in the Traceries could serve as a point of departure for discussions of the numerous influences that informed black arts aesthetics in the twentieth century.29 Continued studies of William Grant Still’s entire output will bring about a greater consideration of the fusions of styles and techniques that shaped his aesthetic for the better part of his career, and will also position him as one whose craft and inspiration extends well beyond black vernacular subjects.

Postscript: The Seven Traceries are in print and available through William Grant Still Music: www.williamgrantstill.com. Inquiries related to purchases or licensing (for classroom use or performances) may be directed to William Grant Still Music. Among the commercial compact disc recordings available are ones by Mark Boozer, Monica Gaylord, Denver Oldham, Richard Crosby, and Seta Karakashian von Bartesch. I would like to thank Peter Shultz, Edward J. Taylor, and Greg P. Newton for their assistance in preparing the graphs and musical examples for this article.

Notes

1Lucius Wyatt, “The Inclusion of Concert Music of African-American Composers in Music History Courses,” 240.

2Claude V. Palisca, Norton Anthology of Western Music, Third Edition, 322-338. The third movement of the Afro-American Symphony first appeared in the Norton Anthology in 1996. Subsequent editions have included the first movement instead of the third movement. See Joseph Auner, Anthology for Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, 163-171. A piano reduction of the second movement of Still’s Africa (1930) appears in Auner’s collection. See also James R. Briscoe, Contemporary Anthology of Music by Women. Tania Leon, Undine Smith Moore, and Mary Lou Williams are included in Briscoe’s collection. I also note the inclusion of notable jazz and blues musicians in the appendices of the Charles Burkhart Anthology for Musical Analysis beginning in 1994 and continuing to the present.

3Judith Anne Still, ed., William Grant Still and the Fusion of Cultures in American Music, 233-302. A thematic catalog of Still’s works can be found here. His pioneering “firsts” include being the first African American to have a symphony performed by a major symphony orchestra in the United States, the first African American to have an opera performed by a major opera company, the first African American to conduct an orchestra

4Much of what has been written on Still’s music involves discussions about black cultural subjects in concert works. See Gayle Murchison, “Current Research Twelve Years After the William Grant Still Centennial,” 119-154. See also Scott Farrah, “Signifyin(g): A Semiotic Analysis of Symphonic Works by William Grant Still, William Levi Dawson, and Florence B. Price,” 29-75.

5This essay does not raise specific points related to performance or performance practice, but the parallels to impressionist styles and techniques are strong. One could consider the Traceries as companion pieces or as a stand-alone suite for studies and programs that involve impressionist themes.

6Stefan Kostka and Roger Graybill, Anthology of Music for Analysis, 522-524.

7Edward Gollin, “On a Transformational Curiosity in Riemann’s Schematisirung der Dissonanzen,” in Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Music Theories, 389-90. Gollin adapts Riemannian theories related to dissonance to analyze harmonic constructs in post-tonal music. Among the passages Gollin analyzes are the first eight measures of “Cloud Cradles” from the Seven Traceries.

8Jon Michael Spencer, “An Introduction to William Grant Still,” The William Grant Still Reader, 8-10.

9William Grant Still, “My Arkansas Boyhood,” in Fusion of Cultures, 14.

10Mark Edward Hussung, “The Solo Piano Works of William Grant Still,” 37-76. Orchestral transcriptions for piano actually date as early as 1934, but Three Visions (1935) was the first composition written for solo piano.

11Carolyn Quin, “Fusion of Styles in the Piano Works of William Grant Still,” in Fusion of Cultures, 177.

12Quin, 177.

13Still, “My Arkansas Boyhood,” in Fusion of Cultures, 14.

14Still, “A Composers Viewpoint,” in Fusion of Cultures, 73.

15Eileen Southern, “Conversation with William Grant Still interview with Still,” in The Black Perspective in Music, 171.

16Dieter A. Nanz, “A Student in Paris: Varesé from 1904 to 1907,” in Edgard Varesé Composer, Sound Sculptor, Visionary, 25. See also Chou, “Varese: A Sketch of the Man and His Music,” 152.

17Chou, 154.

18Still, interview by R. Donald Brown, 9. See also interview by Robert A. Martin, 25.

19Still, “A Symphony of Dark Voices,” in The William Grant Still Reader, 138. The other essays, “The Men behind American Music” (114-15) and “Fifty Years of Progress in Music,” (184) are also reprinted in this collection.

20Hussung, 111—112.

21Verna Arvey, notes to the Seven Traceries, original publication in 1940. Arvey also noted that the titles for the pieces “were suggested to the composer by the music—the music did not arise from the titles.” This draws an intriguing conceptual parallel to Claude Debussy’s presentation of titles in the Preludes (1910-1913).

22Richard Crosby, “An Introduction to William Grant Still’s Seven Traceries,” included in the 1999 edition of the score.

23Kostka and Graybill, 522.

24Still, “The Structure of Music,” in The William Grant Still Reader, 175.

25Octatonic scales consist of alternating half and whole steps. Because they can be divided into two fully diminished seventh chords, they are also known as diminished scales. For this essay, I use Stefan Kostka’s labeling system presented in Materials and Techniques of Post-Tonal Music (Fourth Edition, 2012). OCT(0,1) is for the collection based on C/C#; OCT (1,2) for the collection based on C#/D; OCT (2,3) for the collection based on D/Eb.

26Quin, 177. Quin notes similar treatments in “Summerland” from Three Visions (1936). The author also identifies planing techniques in “Fairy Knoll” from Bells (1944).

27Lawn and Hellmer, Jazz Theory and Practice, 114. Regarding tritone substitutions and jazz performance practice, Lawn and Hellmer state that the “principle dictates that a dominant seventh chord may be replaced by another dominant seventh whose root is a tritone (augmented fourth or diminished fifth) away from the root of the original chord.”

28Nicole Biamonte, Augmented Sixth Chords vs. Tritone Substitutes. “Jazz theory textbooks uniformly present the technique of tritone substitution as applying to dominant-function chords, and some even refer to dominant substitution rather than tritone substitution [14] … In tritone substitutes that resolve to tonic harmonies, b2 generally resolves down to 1, but 7 is equally likely to resolve up to 1, to move down to 6 in an added sixth chord, or to be held constant in a tonic major-seventh chord. [15]”

29Wyatt, 247-48. Wyatt offers more examples from the many “musical resources” from where black composers draw inspiration and influence.

Bibliography

Auner, Joseph, ed. Anthology for Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2013.

Biamonte, Nicole. “Augmented-Sixth Chords vs. Tritone Substitutes.” Music Theory Online 14/2 (2008). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.2/mto.08.14.2.biamonte.html.

Briscoe, James R., ed. Contemporary Anthology of Music by Women. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Chou, Wen Chung. “Varese: A Sketch of the Man and His Music.” The Musical Quarterly 52/2 (1966): 151-70.

Farrah, Scott David. “Signifyin(g): A Semiotic Analysis of Symphonic Works by William Grant Still, William Levi Dawson, and Florence B. Price.” Dissertation. Florida State University, 2007.

Floyd, Jr., Samuel A., ed. Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance: A Collection of Essays. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

_______. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Gollin, Edward and Alexander Rehding, eds. Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Music Thoeries. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Hussung, Mark Edward. “The Solo Piano Works of William Grant Still.” Thesis. University of Cincinnati, 1998.

Kostka, Stefan and Roger Graybill. Anthology of Music for Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2003.

Lamb, Ernest. “An African American Triptych.” American Music Research Center Journal 14 (2003): 65-90.

Lawn, Richard J. and Jeffrey L. Hellmer. Jazz Theory and Practice. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1993.

Meyer, Felix and Heidy Zimmermann, eds. Edgard Varese: Composer, Sound Sculptor, Visionary. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2006.

Murchison, Gayle. “Current Research Twelve Years after the William Grant Still Centennial.” Black Music Research Journal 25/1 and 2 (2005): 119-54.

Oja, Carol J. “‘New Music’ and the ‘New Negro’”: The Background of William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony.” Black Music Research Journal 12/2 (1992): 145-69.

Palisca, Claude V. ed. Norton Anthology of Western Music. Third Edition, Volume 2. New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1996.

Smith, Catherine Parsons. William Grant Still. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

___. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000.

Soll, Beverly. I Dream A World: The Operas of William Grant Still. Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Southern, Eileen. “Conversation with William Grant Still.” The Black Perspective in Music 3/2 (1975): 165-76.

________. The Music of Black Americans: A History. Third Edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Spencer, Jon Michael, ed. The William Grant Still Reader: Essays on American Music. A Special Issue of Black Sacred Music: A Journal of Theomusicology 6/2. Duke University Press.

Still, Judith Anne, managing editor. William Grant Still and the Fusion of Cultures in American Music. Flagstaff, AZ: The Master Player Library, 1995.

Still, Judith Anne, Michael J Dabrishus, and Carolyn A. Quin, editors. William Grant Still: A Bio-Bibliography. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

Still, William Grant. Interview by R. Donald Brown. California State University, Fullerton. November 16, 1967 and December 4, 1967. Transcript.

____. Interview by Robert A. Martin. May 1964. Transcript

Varese, Edgard and Alcopley. “Edgard Varese on Music and Art: A Conversation Between Varese and Alcopley.” Leonardo 1/2 (1968): 187-95.

Wyatt, Lucius R. “The Inclusion of Concert Music of African-American Composers in Music History Courses.” Black Music Research Journal 16/2 (1996): 239-57.

Scores

Still, William Grant. Bells, “Fairy Knoll”. Los Angeles, CA: Delkamp Music Publishing Company, 1944.

Still, William Grant. Bells, “Phantom Chapel”. Los Angeles, CA: Delkamp Music Publishing Company, 1944.

Still, William Grant. Seven Traceries. New York: J. Fischer, 1940.

Still, William Grant. Seven Traceries. ed. Richard Crosby. Flagstaff, AZ: William Grant Still Music, 1999.

Still, William Grant. Three Visions. New York: J. Fischer, 1936.

Recordings

von Bartesch, Seta Karakashian. Rarely Performed Piano Works, Vol. 2. Romeo Records 7298, 2013, compact disc.

Boozer, Mark. William Grant Still: Piano Music. Naxos (American Classics), 8.559210, 2005, compact disc.

Crosby, Richard. An American Portrait. Capstone Records, CPS-8671, 1994, compact disc.

Gaylord, Monica. A Treasury of Works for Solo Piano by Black Composers. Music and Arts CD-737, 1992, compact disc.

Oldham, Denver. Africa: The Piano Music of William Grant Still. Koch International Classics 3-7084-2 H1, 1991, compact disc.