Music teacher preparation programs in the United States tend to have at least one thing in common - they stem from a traditional music curriculum where students with various program emphases have a common core of classes and experiences. The thinking here is that no matter what a music major plans to do after graduation there exist musical “basics” in which every music student must be proficient. These tend to include performance skills on a principal instrument developed both through private study and ensemble experience, knowledge of note reading and music theory, and an understanding of the history of the Western musical canon. Most often other experiences are also involved, including keyboarding skills and basic conducting competence. All of these, performance, notation, theory, history, keyboarding and conducting, tend to be based on a particular perspective from a classical musical tradition with roots in 18th century Western Europe.

This model for the training and education of future music teachers has over one hundred years of history (Campbell, 2007; Cutietta, 2007; Emmons, 2004; Jones, 2005, 2007; Kratus, 2009; Myers, 2009; Robinson, 2002). The model has itself become tradition, and is taken for granted as correct and necessary. I want to propose, however, that it is possible this model is based on a flawed premise. The general assumption that what is good for one, is good for all, may be misguided. The idea that different types of degree programs offered by schools and departments of music, some leading to vastly divergent career paths, require the same basic skills and understandings may well be inaccurate. Investigating the music core, the Report of the CMS Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major, released in November of 2014, provides recommendations for progressive change in the undergraduate music-major curriculum (Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major, 2014). Included are suggestions for how different types of music programs might be transformed.

The traditional model is based on the elitist view that there is one best way to approach musical understanding. It just happens to originate from the age-old process used to produce performers to fill symphony orchestra positions. A role understood by those that do it as the crème de la crème of musical involvements. The devotion to this process trivializes all other musical experiences which obviously do not measure up to the standards of “high art.” As Humphreys (2004) has noted, the profession has been driven by a “missionary-like zeal to reform society’s musical tastes” and that in so doing we have “lost countless opportunities to participate in the culture of American music as it was and is, as opposed to how the profession wants it to be” (p. 100). In a critique of the music education system in the United States, composer Libby Larsen suggests “...we have a system that has grown up around a particular repertoire that is a really small percentage of the music that is in our world”...[music education]...“faces a crisis of relevancy to the musical world in which we live” (Larson, 1997).

The issue at stake here has to do with the definition of musicianship. Real musicianship, according to this classical approach happens only one way. To be considered musical one must be an expert performer on an orchestral instrument, piano or voice, and perform the significant works composed by masters for their instrument. In support of this, a musician is one who reads and writes musical notation, interprets 18th and 19th century counterpoint, and understands the classical music lineage from plainsong to neoclassicism and to polystylism. Other involvements with music are not considered as honorable, and do not lead to the same lofty level of musical understanding or musicianship.

We have bought into this thinking for far too long. The sheer number and diversity of different musical involvements available in the early part of the 21st century is nothing short of amazing. There are certainly as many breeds of musicianship as there are different musical involvements. I have suggested before (Williams, 2014) that there is no wonder why we have trouble interesting students in school music programs when we offer basically one type of musical experience and we continue to marginalize the various musical involvements students themselves find most meaningful. We implicitly, and often explicitly, communicate to students, “come out of your mire of unmusical clutter, and I will help you understand real music!” Perhaps Emma Lazarus was thinking of school music teachers when she wrote,

1 Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

The traditional higher education music training model seems to make sense for those interested in a classical music performance career. But even here, with the recent elimination of so many traditional music performance opportunities, a strict devotion to tradition could be questioned. For students specifically interested in k-12 school music teaching, however, this model of curriculum may simply no longer be effective. It could be, perhaps, the single greatest impediment to improving the status of the music education profession in the United States. If we wish to reach the next generation of young people and help them develop musically then it is imperative that we stop belittling the musics and performance practices they find meaningful, and embrace pedagogies that are most appropriately suited for these. Jones (2006) suggests that,

In order for music education to regain relevance and return from the musical fringe to the musical mainstream we must rethink the curriculum. A 21st Century music curriculum must be designed to invigorate musical learning and to musically empower students in pluralistic societies... it should connect students with the musical environment in which they live. In order to connect students’ in-school music education with their out-of-school musical lives, music offerings must emphasize music they will find in their communities. The goal is to have students participating in music both within and outside of school so graduates will continue performing and enjoying a wide range of musical offerings within their communities throughout their lives. (p. 12).

A typical response to this type of suggestion usually goes something like, “we don’t need to throw out the baby with the bath water.” 2 This generally suggests we shouldn’t change tradition, so instead let’s nibble around the edges basically leaving things the way they are. It’s time we realize the baby is more than 100 years old and it’s well past time for it to get out of the bath water anyway. It is very possible, as we move further into the 21st Century, that nibbling around the edges of curriculum change is absolutely not enough.

The issues facing music teacher preparation programs run deeper than curriculum and pedagogy and also include admission procedures. Students are typically admitted as music majors based on their performance ability measured through the lens of the classical music tradition. More often than not a high school student with a musical background different from this tradition has little chance of entering a music education program at the college level. With few exceptions, a student who has developed remarkable aural skills and performance technique on the guitar playing with a garage band would not normally qualify for admission through a college audition. The same is true for a student who has advanced electronic music understanding creating beats, writing songs, and performing with a hip-hop group. Not only would these students normally not be successful entering most college music education programs, it is doubtful they would even consider auditioning for admission since they probably had no opportunity for musical participation in middle and high school music classes. They would have already learned that there was no place for them in school music (Hargreaves, and Marshall, 2003). Jones (2006) suggests

We can no longer limit admissions to those who perform on concert band and orchestral instruments, and sing classical music... We must embrace a wider array of musicians with varied backgrounds and experiences. In the end, we must consider that the future leaders of our profession might not necessarily be members of school based large ensembles with resumes of participation in honor band, choir and orchestra but are perhaps garage band guitarists, self-taught keyboard and drum-set players, and vocalists who have played in clubs and copy an aesthetic more regularly found on Broadway and MTV than in the concert hall (p. 15).

Bernard (2012) agrees:

Individuals with non-traditional backgrounds, because they may not be tied to the way things have always been done in music education, may be able to think outside the box in terms of repertoire, musical activities, teaching strategies, and performance practices, bringing their unique musical experiences and perspectives to the ways that they structure their classroom practice. They may be able to incorporate different musical styles into their teaching–musical styles that may be more interesting and meaningful to their students. They may thereby be able to increase the relevance of the field of music education by forging stronger connections between the music that their students listen to outside of school and the music that their students encounter in music class or rehearsal (p. 6).

We are certainly losing out on a good number of potentially outstanding music teachers because our devotion to a singular model of musicianship also impacts the admission process. New curriculum models need to consider both content and pedagogy as well as admission.

What might a music teacher preparation curriculum look like that doesn’t begin and end with a focus on the classical tradition? I would think there are a multitude of possible approaches, but our devotion to a single model has had two results. First, the vast majority of tertiary music education programs are nearly identical, and as a consequence most k-12 school music programs consist of the same basic offerings for students. You don’t, however, have to be very astute to realize music offerings in a rural Iowa school, an inner city Detroit school, and a suburban school in Miami could be radically different and serve the greater majority of students in those schools most appropriately. It would seem to follow that there could be variation in the type of training students receive in different teacher preparation programs as well. Some college/university programs might focus on traditional school music making while others could place heavy emphasis upon more progressive methods and pedagogies. Prospective music education students could choose the type of program that most interests them and best serves their personal needs.

Ideally, music teachers would be experts at all that can be known about and done with music, but we deal with a finite amount of time and credit hours, and priorities need to be made. I’m going to suggest that a good number of priorities could focus on musical aspects that are different from those of the traditional classic tradition. What follows, then, are some general concepts that might drive one possible new look at teacher preparation curriculum planning, resulting in music education graduates that are better prepared to reach larger masses of students considering the realities that make up 21st Century schools. Bernard (2012) suggests there is a need for such diversity.

As the musical world of today becomes more and more wide ranging, and as music is being shared across national boundaries, music educators must understand and participate in a greater array of musical styles and traditions than ever before. Today’s musical reality demands music educators who can support their students as they explore a varied repertoire – varied in terms of its historical context, musical style, and cultural origin.

I suggest such a curriculum would also create a considerably more attractive environment for which non-traditional students could, and would, audition. I am asking the baby to exit the bath water. I am cleaning out the tub. And I am filling it with fresh, clean water. In doing so I will include a number of proposed changes, which could be implemented in different ways and in different combinations.

1. Music Theory and Music History

Traditionally, theoretical and historical music study for music majors involves mainly Western European classical music. These are typically taught in classes separated from the rest of the curriculum, a model, which for decades has been questioned by proponents of comprehensive musicianship who encourage more integration of all aspects of musical development (Contemporary Music Project for Creativity in Music Education, 1971). I propose a curricular model where theoretical and historical understandings are approached in large part by students as they need them to develop creative musical skills. These skills, in many cases, being different than those normally emphasized by traditional music teacher preparation programs that focus very heavily on performance, both alone and in large groups.

In such a model students would not necessarily take separate history and theory classes with the possible exception of advanced electives. In order to better facilitate active music making in all the various ways available in the 21st Century, basic theory and history, involving both classical and vernacular musics, would be learned while developing musicianship skills through activities including performing, listening, composing, arranging, copying, improvising, and conducting. In practice this model might revolve around a series of basic musicianship courses taken by students over several semesters and complemented by online materials allowing for a flipped classroom experience (Grant, 2013; Heng Ngee Mok, 2014; O’Flaherty and Phillips, 2015; Wilcox Brooks, 2014) where knowledge learned prior to class time can be applied to musical problem solving presented to students in class. Such courses could include class experiences in addition to participation in k-12 school practica working with school-aged students (as well as placements in community based settings with younger and older persons). These musicianship courses would serve as a center hub experience, and skills and understandings developed in all other music education courses would tie directly back to here.

Such courses would call for a very different teaching model in which faculty would help students discover and apply necessary knowledge and skills. Learning would most often be proceeded by a student needing to know something in order to accomplish a task. This model would fit nicely into a classroom emphasizing informal learning concepts and student directed learning where students are given significant autonomy over their learning (Green, 2008). Many assignments would be broadly defined allowing students, sometimes individually, sometimes in small groups, opportunities to recognize problems and decide how to resolve them. This is a very different pedagogical approach from traditional large ensemble classes where teachers normally recognize problems a priori and decide how to resolve them without significant input (if any at all) from students.

Some thought about musical styles is important at this point. When given autonomy to choose, often students will select to work with musics outside of the classical canon. Many times these styles will require different sets of theoretical and historical knowledge than are common in classical music. It can also be expected that performance ability will need to be developed on instruments that are not a part of the Western European orchestral tradition. Some (or most) of this might be beyond the teacher’s base of knowledge. Depending on how approached, this can create an awkward situation, or a wonderfully rich environment for student self-discovery and peer interaction, along with guidance from the teacher, to facilitate learning.

2. Ensemble Participation

Traditional teacher training includes extensive participation in ensembles that tend to share a few common characteristics. These ensembles are large in size, ranging from around 20 to over 80 students. Students are typically assigned to a particular ensemble, often for multiple semesters. They are led by a teacher called a “director.” This individual makes practically all the creative and artistic decisions for students, including what music will be played and how and when it will be performed. This music is most often written by others specifically for each type of ensemble (seldom is the strict boundary between student performer and composer breached). These ensembles rehearse over a period of weeks and then perform a formal concert where students dress in matching uniforms and have no direct interaction with the audience outside of playing their instruments. Audience members, in turn, have no direct interaction with students except for polite applause after each musical number is completed. And finally, each ensemble’s instrumentation, or arrangement of voice parts, is set by convention and tradition, and during rehearsals and concerts students either sing or play instruments. It is quite rare that both happen at the same time, and it is even less frequent that individual students will do both.

I propose that students need to be encouraged to develop musicianship skills through a variety of ensemble settings as determined by their needs. These ensembles would mostly look more like those found in vernacular and popular music settings (Campbell, 1995; Jaffurs, 2004; Westerlund, 2006). They would mostly be small, perhaps ranging in size from two to eight students. With faculty guidance, students would self-assign to one or more ensembles at any given time, however, personnel in ensembles would remain flexible throughout a semester to react to the needs of the music being performed over time. Students might remain in one ensemble for several semesters while changing in or out of others during the same time. Students would take on the leadership roles of their ensembles while teachers would serve roles of supporter, coach, mentor, teacher, and facilitator. Students then, would be primarily responsible for making creative and artistic decisions, including what music will be played, how and where it will be performed and on what instruments. Generally, students would take on more of a participatory role than found in traditional school music settings (Regelski, 2013; Tobias, 2013; Turino, 2008; Woody and Parker, 2012). The music used could come from a variety of sources they help select, including traditionally composed literature, copying and arranging existing music, and/or original music composed by individuals or groups of students. Ideally, students would use a combination of music sources, and rely more on original pieces as they mature. Concerts would also take on more of a participatory nature rather than the traditional presentational type of performance (Regelski, 2013; Tobias, 2013; Turino, 2008; Woody and Parker, 2012). Students could have opportunities to plan every aspect of a concert, including programing, music preparation, creating multimedia aspects, inviting and working with guest performers, selecting and scheduling venues, and promotion. Potential venues would expand beyond those typically used by school ensembles to include community centers, youth centers, certain clubs, lounges, and sports bars, among others. The internet provides another venue for live and recorded performances. In general, the music education profession continues to ignore the vast potentials provided by online environments - this could be the topic of another complete paper.

Such participatory experiences, both in rehearsals and concerts, help students develop a more personalized musical identity than that typically resulting from traditional school music study. Woody and Parker (2012) suggest a ‘personalization’ of musical involvement may be the key to developing lifelong musical participation. Such personalization results from individual autonomy, self-resourcefulness, and involvement with personally meaningful, enjoyable and rewarding experiences - experiences that do not rely on an ensemble director, printed sheet music and an externally imposed schedule in order to make music.

These student led ensemble courses would be co-requisites taken each semester along-side the basic musicianship core classes. In their ensembles students would typically rehearse over a period of weeks while performing regularly in class, sometimes performing work completed, but mostly playing pieces in varying degrees of resolution. Discussion between student groups concerning musical aspects would be encouraged surrounding these performances. In addition, students would perform in informal settings in and out of school, some of which the students arrange themselves. A more formal concert could be held as well, but this should not be the primary focus. Both formal and informal performances would probably include aspects of lighting, staging, acting, movement and multimedia. During all performances there would be regular communication between performers and audience, and the audience would feel free and welcome to move, dance, sing, and wail as appropriate while music is being performed. Individual audience members could even be uploading video clips to Facebook during concerts!

Finally, the instrumentation for each piece of music would be determined by the students performing, and could vary wildly depending on the needs of the music and the capabilities of the students. Individual students might perform on several different instruments during a single piece or concert, and practically all performances would include both singing and playing on instruments, often with several students doing both at the same time.

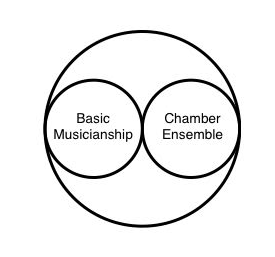

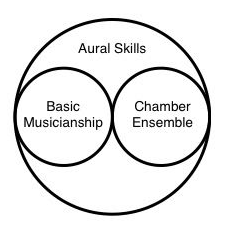

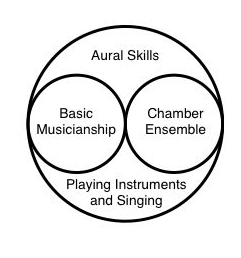

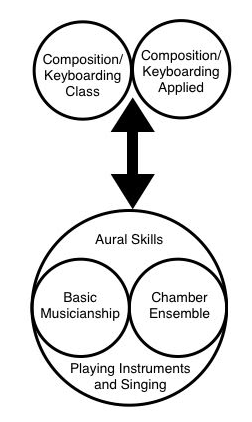

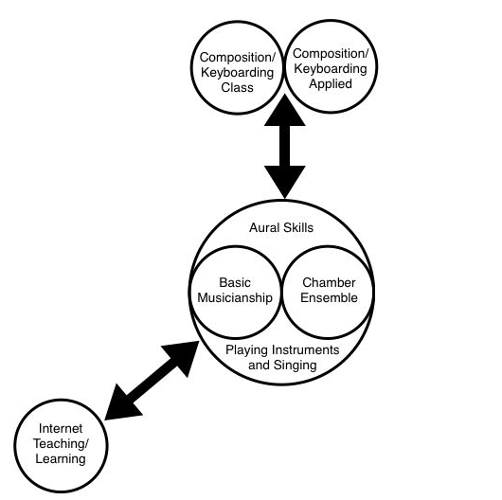

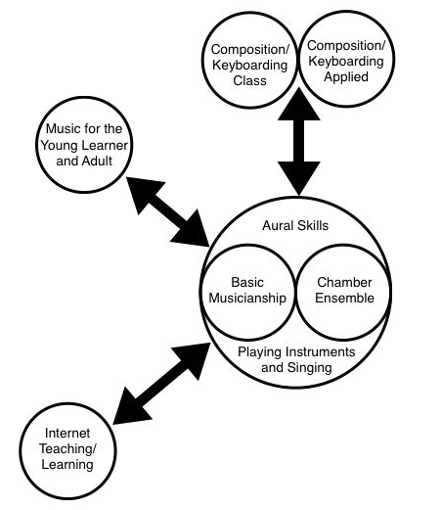

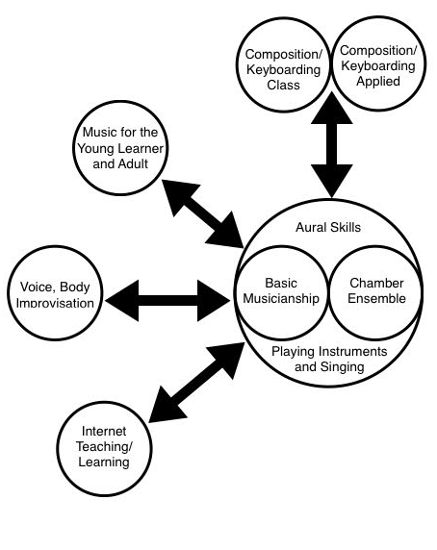

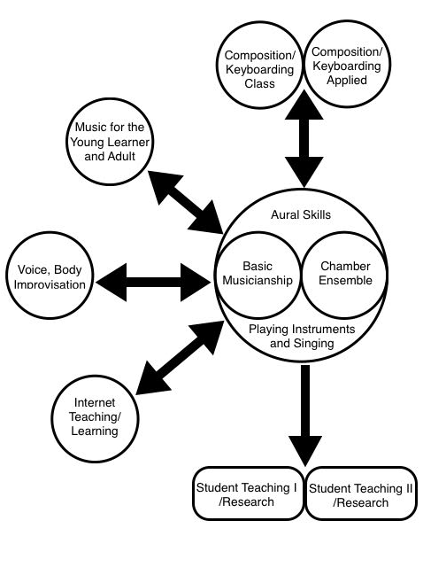

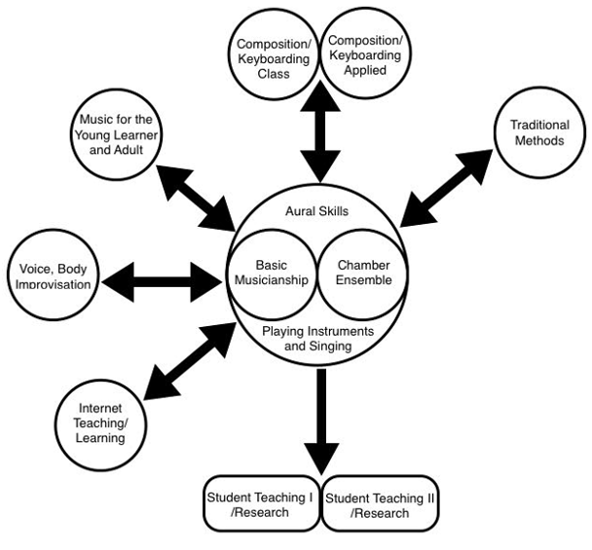

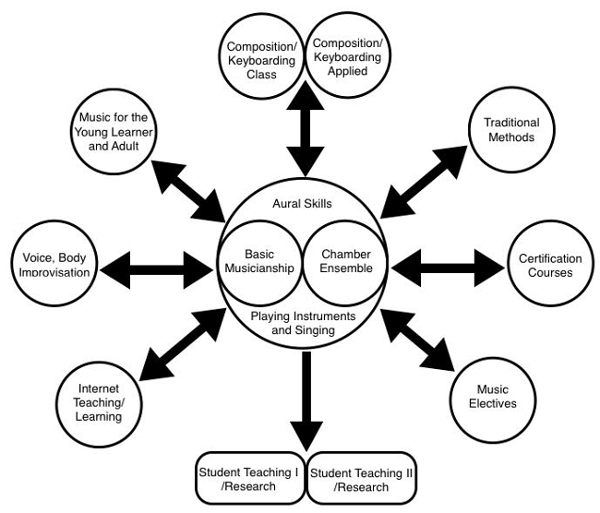

The core of this proposed curriculum model then is a series of basic musicianship courses along with co-requisite chamber ensemble classes. Students would take this pair of coursework for as many semesters as possible throughout their undergraduate experience.

3. Aural Skills

While the development of aural skills is normally addressed in traditional teacher preparation programs, the necessity of aural understanding is often more important in many vernacular styles of music where conventional notation is not typically employed (Green, 2014). Here, aural skills are most often developed through the aural copying of popular songs and by song writing in small groups. I propose a curricular model where students receive significant experiences with such activities over an extended period of semesters. These experiences would form the nucleus of both the basic musicianship courses and the chamber ensemble experiences. This could take various forms, but in all cases students would be problem solving by ear to realize musical results tied directly to their own music making activities. Ideally, this would happen most often with small groups of students working together creating music. These activities wouldn’t have to solely involve popular music styles and could also include students creating their own original music. The essential idea is to get students to open their ears more by making them less dependent on written notations, and the model of the vernacular musician provides an excellent blueprint.

As with theoretical and historical concepts, this would call for a very different teaching model in which faculty would help students discover and apply necessary knowledge and skills. Again, understanding would be approached by students as needed to develop musical skills. Instead of learning abstract aural skills in a pre-determined sequence, students would be led to develop skills as they face musical problems they want to solve.

4. Private Study

In the classical tradition students are expected to devote themselves to the mastery of a primary instrument. This is done through an apprenticeship model where students study privately with one teacher and they present various solo juries and recitals to demonstrate achievements. I suggest that while this model may well fit the needs of music performance majors, it is not significantly broad enough for the future music teacher. Concentration on a primary instrument is one thing, but a singular devotion to one instrument will no longer meet the demands of 21st century teaching positions.

While all students interested in a music teacher preparation program enter with some level of skill on a primary instrument, I propose that students need to be encouraged to develop musicianship skills through several different instruments. The selection of instruments would be guided primarily through individual student interest (every student does not need to study the exact same set of instruments). I suggest there is a significant difference between learning technique in order to play an instrument and developing musicianship through playing instruments, and it is the latter that is most important for the pre-service music teacher. This is best developed when tied directly to their own music making activities (performing, listening, composing, arranging, copying, improvising), working in small groups, where the students have a good deal of autonomy in how they complete assignments.

Let’s stop at this point and consider two important aspects related to instrument study for pre-service teachers. First, music education programs have traditionally separated performing on instruments and singing. Students normally study one or the other and often identify themselves as either a vocal major or an instrumental major. This translates to school music programs that are divided into instrumental classes and vocal classes. And often this division runs deep. Yet this dichotomy is not found in most aspects of youth musical culture outside of the schools. Almost all popular musics combine singing and playing on instruments, often with individuals doing both at the same time. This is also an important aspect regarding comprehensive musicianship and providing students with a broad sense of being musical - concepts that are pivotal if we want to help prepare pre-service music teachers to reach more diverse populations of students. I propose that music education programs need to prepare pre-service music teachers in both instrumental and vocal performance as equally as possible. Future teachers need to leave such programs comfortable singing and playing on instruments at the same time, and ready to help their future students do the same.

Second, the range of instruments for study needs to be expanded well beyond the traditional orchestral instruments to include instruments used in popular music styles as well as instruments used in world and folk musics. This should certainly include various electronic and digital instruments. There is a difficult reality to which music education programs must face. The traditional orchestral instruments, as well as traditional forms of choral singing most often associated with classical music (and school music), exists only on the margins of musics that have meaning to the greater majority of k-12 students. Our profession’s inability to confront this matter (and avoidance) is in large part responsible for the low percentage of students that choose to participate in secondary school music programs. I propose that music education needs to concentrate on instruments, and the styles of music associated with them, that hold the greatest meaning to students. This would go well past guitars and drums, keeping in mind that the microphone, an iPad, a turntable, and a drum machine are all musical instruments, and new instruments are appearing all the time (more on this later).

All of this would call for a very different teaching model in which faculty would help students discover and apply necessary knowledge and skills on various instruments and the voice as students desire or need them to solve musical problems they encounter. Much of this learning would take place in small group settings, instead of through private instruction, where students would be involved in peer-teaching/learning guided by teacher input.

We should recap some overarching concepts that connect the ideas presented to this point. What is being proposed would have students involved in core musicianship classes, over several semesters, where their musical development embraces a good deal of autonomy over what is learned and in what ways it is learned. Instead of controlling the classroom setting, faculty facilitate student musical growth by providing wide-ranging assignments where students encounter musical problems that need to be solved. The sequence and scope of what is learned is mostly not predetermined, but instead realized as students find the need to develop skills and knowledge to get past obstacles they encounter as they write, arrange, copy and perform music in small groups. This model would then serve as the basis for a wide variety of different types of k-12 music programs as well as music across the lifespan settings. Of course, this model is nothing new as it is borrowed from concepts of comprehensive musicianship as well as from methods used by popular musicians outside of school settings. However, it is quite different from the traditional undergraduate music education curriculum that has been used to produce teachers who concentrate (most often exclusively) on band, orchestra and choral ensembles.

5. Composition/Improvisation and Keyboard Skills

While traditional music teacher preparation places primary importance on performance, a new look at teacher training could emphasize creative production instead. As a different model I propose students should be involved with courses specifically targeting both acoustic and electronic composition. Such courses might be combined with keyboarding skills that are normally developed in separate courses. Both compositional and keyboard understanding and technique would be developed side-by-side. Expertise developed in these composition/keyboard courses should tie directly to work being done in the core musicianship courses, so that understandings are approached by students as they need them to develop creative musical skills. It is here, more than with performance, that private applied instruction might be beneficial to the developing music teacher. In addition to classwork, some number of semesters of private instruction in composition/keyboarding would provide a foundation of musicianship on which the future music teacher can base his/her teaching skills.

6. Digital Technology

The traditional approach to delivering technology instruction normally involves one or two stand alone classes devoted to certain software titles. I propose instead that work with digital technologies should be infused throughout the degree program. Music technologies relevant for aspects of any course should be addressed during that class. Since learning is enhanced when students have a real need to apply what is learned, technology skills should be approached by students as needed to develop musical skills as they face musical problems they want to solve.

As with the other aspects of a new curriculum model this would call for very different teaching methods in which faculty would help students discover and apply necessary knowledge and skills. As mentioned earlier, much of this work might be complemented by students making use of online materials allowing for a flipped classroom experience where knowledge learned prior to class time can be applied to musical problem solving presented to students in class. However, there is a serious issue here for music education faculty. It is common that teachers involved in teacher preparation have at least a basic background in music history, music theory, aural skills, solo and ensemble performance, and even to some level, aspects of composition. This is not necessarily true for technology. There are still music education faculty that have not developed any skills with basic digital technologies. These technologies are no longer extras that can be left only to experts. Instead, they are now as basic to music education as any traditional aspect. It is essential that all faculty involved with music teacher preparation have at least a basic understanding of technologies involved with performance and recording. Not everyone (or perhaps anyone) can become expert with all the different relevant technologies, but we must begin to recognize how important it is for all educators involved with music teacher preparation to have at least a basic proficiency with a variety of digital and electronic ways to make, record, mix and edit music, as well as how to use online pedagogical teaching tools. Our students, who will be teaching in an increasingly digital world, deserve no less.

We should take a moment to look at the range of technologies that could be involved in a teacher education program. It simply isn’t enough to have students notate using a computer. They need to use a wide range of hardware and software in live performance. They need to record their performances, and they need to edit and mix these recordings. They need to use recordings as part of live performance. They need to understand how to perform with microphones and speakers, and how to mix sounds in live performance. Additionally, students should be involved with image and video shooting and editing and mixing images and video with sound. No doubt this list will change and grow over the coming years, but we must recognize the ever-increasing importance of electronic and digital music in the musical life in which pre-service music teachers will live and work.

7. The Internet

Every year I tell my students that the internet is not a fad – that it isn’t going away. They laugh, but they seldom recognize the issue. The humor, I’m afraid, is that you could assume the music education profession believes the internet is a passing fad and that it will not have any significant impact on what we do in the classroom. This is a very dangerous notion. The internet has already had a significant impact on education and the technology is only in its infancy. We can no longer ignore the possibilities the internet presents, as well as the challenges it causes for traditional face-to-face instruction. New curricula for music education must include pre-service teachers both taking online music classes as students, and developing skills and strategies for delivering various types of music instruction online. One possibility for this might be a course where students both learn about and encounter online teaching techniques and also practice these techniques - first experiencing online music instruction in a number of areas including live and recorded performance, and composition. Then, they need to have opportunities to actually teach students of all ages (including those younger and older than students in k-12 schools) in a variety of online musical settings (including both synchronous and asynchronous environments.

Work in the basic musicianship and chamber ensemble sequence would help inform assignments in such a class, and understandings developed in the internet teaching course would also relate back to these core classes. While we can’t see exactly what the future of education will be like, we can be sure it will increasingly involve the internet and new methods of teaching/learning and we have a very serious obligation to our pre-service music teachers to help them consider the possibilities and to develop related skills.

8. Continuing Education

Traditionally, music teacher preparation has focused almost exclusively on students in grades k-12. As we continue to move into the 21st Century it is simply too narrow a focus to only consider students aged 5-18. This is especially true as teaching/learning becomes more assessable through the internet. In a new music education curriculum it will be important to address the needs of people beyond those that fit within the traditional definition of “school.” Work in courses targeting young children and/or adult learners could be tied, to some degree, to work done with internet based teaching courses. While certainly not the only structure for reaching a wider audience, the internet would present a wealth of opportunities. As pre-service teachers develop strategies for reaching out beyond the traditional school population, they would also use this knowledge to inform work done in their basic musicianship and chamber music classes.

9. Incorporating Other Arts

An area in which traditional music education has had little success involves the inclusion of other art forms. Music students can gain significant artistic understanding by incorporating elements of video, photography, dance, visual art and theater into their work as creative musicians. New curricula for music education should involve pre-service teachers learning about and experimenting with various arts forms. Their growing understanding in these areas would then help inform work done in the basic musicianship and chamber music classes. A particularly helpful experience for future teachers would be a course where they are asked to stretch themselves physically through voice and body improvisation. Such a course could help students explore the elements basic to acting and stagecraft through active participation. An understanding of these types of skills is quite valuable for teachers and conductors and would certainly help students grow musically through the basic musicianship and chamber music ensemble course sequence.

10. Student Teaching/Practicum Experiences

Providing opportunities for pre-service teachers to work directly in genuine teaching situations with actual students (of all ages) is unquestionably a vital part of teacher training. Music education students traditionally have opportunities for in-school practicums connected to various methods courses. Such experiences often place students in schools a few hours per week to practice teaching with an in-service music teacher. Following some number of semesters that include practicum involvement students normally then complete a semester of full time student teaching which typically involves working in schools, all day, Monday-Friday, for most or all of an entire semester. While practicum experiences provide pre-service teachers a good introduction to teaching, and the student teaching semester is an exceptional final experience, a new model of music education might add a smaller version of student teaching during the semester prior to a final student teaching experience. This initial semester of student teaching could place students in schools for two or three full days per week providing significantly more practice teaching experience and an excellent transition between the traditional practicums and the full time student teaching semester. Providing such a valuable, and practical experience within the traditional music education program has proven difficult primarily because of the number of classes, ensembles and private study requirements normally associated with this degree track. Alternately, this prefatory internship might come in the form of a study abroad experience for part of a regular semester or even as a short summer or intersession. There are several locations that might afford pre-service music teachers an outstanding experience working within a different culture as well as providing an opportunity to work with teachers who have significant experience with student centered and informal learning pedagogical techniques. Some of the possibilities would include schools in the United Kingdom as well as many areas of Scandinavia and the Commonwealth of Australia.

Both semesters of student teaching could also include a seminar experience where all students involved in student teaching would meet together on a weekly basis with music education faculty to discuss their experiences and to explore topics related to upcoming job searches including interviewing, and resume writing. In addition, students would investigate basic research techniques during their first semester of internship, and then they would have opportunities to conduct small scale research studies with the students they are teaching during their second semester.

11. Traditional Music Education Coursework.

Graduates from non-traditional teacher preparation programs, as described here, would be primarily prepared to offer classes that do not currently exist in many k-12 schools (more on this later). Just as some traditional teacher education programs include limited course work addressing non-traditional music areas (i.e.: a guitar methods course, or a digital technology course) a teacher education program with an unconventional focus could include course work to help students develop basic skills with traditional settings. A pair of methods courses dealing with instrumental and vocal performing ensembles would be one example, especially if these courses included practicum experiences working with k-12 students in schools.

12. Music Electives and Certification Courses.

To complete this proposed model, state required certification courses that could not be covered through music education classes would need to be added. Most states have a set number of such courses that all pre-service education majors must complete in order to become certified to teach. It would be important for music education professors to help students connect material from these classes back to the basic musicianship core. Not doing so would allow students to dismiss much of the valuable information provided by such course work. Finally, it would be very important for an undergraduate music education degree program to include some number of elective hours. This would enable students to explore areas of their interest not required for the degree program. It would also allow an opportunity to take additional course work or advanced courses related to certain requirements. In the present proposal this could include more traditional offerings no longer required, and/or additional composition courses, advanced theory or history courses or educational and psychological classes.

With the addition of the core of general education courses required for all students, this is a complete model for a new curriculum in music education. This specific model challenges many of the basic assumptions on which traditional curricula are based – something I feel is desperately needed, and it would produce a vastly different type of music teacher. Presented here, however, is only one possibility among many, and even the model described here could be modified in various ways to achieve desired results at different institutions.

The primary intent of the traditional model of music education is to prepare music education majors to lead large ensemble based learning, and specifically to be band, choir and orchestra directors. The singular focus of this model has kept the profession from adapting to a changed and continually changing society and musical culture. In contrast, the proposed model presented here would lead to a broader framework for music teacher development. It would create a very different type of music teacher who would be prepared to meet students, of all ages, where they are and take them to a fuller understanding of their personal musicianship. It would generate music teachers who were flexible enough to adapt their training to the needs of their students, and to the ever-evolving musical cultures of the 21st Century. The music education profession desperately needs this adaptability as we move into an uncertain future.

A listing of potentially new music courses that could be offered by graduates from music teacher preparation programs, such as that described here, is seemingly unlimited. Some examples would involve a specific instrument or focus as in guitar classes, rock music classes, hip-hop classes, salsa music classes, Country and Western music classes, keyboarding classes, Steelband classes, Irish fiddling classes, drumming classes, digital recording or production classes, live digital performance classes, musical theater classes, and so on. Many of these could be offered in different versions for face-to-face instruction or in an online format. Most, if not all, might make use of a student-centered, informal learning approach where students primarily (or at least in large part) learn as part of small cooperative groups where they have significant autonomy concerning music choice and content, and where appropriate they make musical decisions in creative ways learning as composers, arrangers, improvisors, instrumental and vocal performers, song writers, lyricists, actors, dancers, producers, etc.

The best possible course offerings, however, might allow students opportunities to chose musical involvements, from across these specific focuses, that interest them to realize assigned musical problems/assignments. In such a class one group of students might create a hip-hop song accompanied by an accordion and harmonica, while another group writes and performs a Country & Western song that includes acted parts to tell a story, while a third group produces a rock-opera using digital instruments, voice and dance. For another assignment in the same class a new grouping of students might arrange a movement of a Beethoven Symphony for Orff instruments, a duo performs an original song accompanied by guitar and bassoon, and another group writes and produces a dance club set for a live DJ that includes lighting effects and planned audience interaction. This type of class could have a variety of different foci at individual schools and could be named something generic like “Modern Music,” “Next Generation Music,” or perhaps just “Music.” Certainly this type of music education is already taking place, however, these occurrences are still rare and anything but typical. Gaulish (2014) describes a high school concert called “Java Jam” that, while not associated with a specific music class, embodies much of what these types of courses would generate.

There is a chicken and egg complication involved here. Where and how does real change begin? Does it start with in-service teachers changing what and how they teach, or does it begin with college music programs producing a different type of teacher prepared to offer music classes that don’t already exist in most schools? For the most part, the profession has tried the former, hoping that in-service teachers, especially young teachers, would make programmatic changes that might help move the profession forward. Not surprisingly, this strategy has resulted in a very slow rate of change as the vast majority of teachers continue to approach traditional music classes in the same traditional ways. What is needed in order to jump start significant change in the profession, I suggest, is the addition of music teachers trained to offer music learning opportunities in new and exciting ways.

On the other hand, there is concern that a different type of teacher would not be employable, as they wouldn’t easily fit into the current model. I want to suggest that it is time we get past this concern. I firmly believe there are enough astute principals, and other individuals who make hiring decisions, who will understand the potentials for students and schools that can be realized by a new type of music teacher – a teacher who has been prepared to reach new populations of students with music programs that have meaning to them. It is this, offering musical experiences to students, of all ages, that they find meaningful and relevant, which we must achieve. Innovative curricula, both as part of music teacher training programs and in k-12 schools, will be necessary, and courageous teacher educators must lead the change.

Based on the twelve proposals and ideas suggested here, the following curricular outline is one possibility that would produce music teachers prepared to offer meaningful music classes to 21st Century students. This specific model challenges many of the basic assumptions on which traditional curricula are based - something that our profession needs. It is also a curriculum for which non-traditional music students would be better equipped to enter. There are, no doubt, many possible modifications that could be made by individual Colleges and Universities to achieve desired results at different institutions, but I would argue that this model is one that would go a long way in helping bring the profession back to relevance in our society.

CURRICULUM EXAMPLE

| Basic Musicianship (6 semesters at four credit hours each) | 24 |

| Chamber Ensembles (6 semesters at one credit hour each) | 6 |

| Composition/Keyboarding Class (2 semesters at two credit hours each) | 4 |

| Composition/Keyboarding Applied (2 semesters at two credit hours each) | 4 |

| Internet Based Teaching/Learning | 3 |

| Music for the Young Learner and Adult | 3 |

| Voice-Body-Improvisation | 3 |

| Instrumental Music Methods | 3 |

| Vocal Music Methods | 3 |

| Student Teaching I/Research Seminar (study abroad) | 3 |

| Student Teaching II/Research Seminar | 12 |

| State Required Teacher Certification Courses | 9 |

| Music Electives (traditional applied/performance, theory, etc.) | 15 |

| University Required General Education Courses | 36 |

| TOTAL | 128 |

Notes

1Emma Lazarus’ poem The New Colossus is graven on a tablet within the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty stands.

2“Throw out the baby with the bath water” is an idiomatic expression and a concept used to suggest an avoidable error in which something good is eliminated when trying to get rid of something bad, or rejecting the essential along with the inessential.

References

Bernard, R. (2012). Finding a place in music education: The lived experiences of music educators with “non-traditional” backgrounds. Visions of Research in Music Education, 22, (accessed October 29, 2013).

Campbell, M. R. (2007). Introduction: Special focus on music teacher preparation. Music Educators Journal, 93(3), 26-29.

Campbell, P. (1995). Of garage bands and song-getting: The musical development of young rock musicians. Research Studies In Music Education, (4), 12-20

Contemporary Music Project for Creativity in Music Education & Music Educators National Conference (U.S.). (1971). Comprehensive musicianship: an anthology of evolving thought: A discussion of the first ten years (1959-1969) of the Contemporary Music Project, particularly as they relate to the development of the theory of comprehensive musicianship, as reported in articles and speeches by those closely associated with the Project. Washington: Music Educators National Conference.

Cutietta, R. (2007). Content for music teacher education in this century. Arts Education Policy Review, 108(4), 11-18.

Emmons, S. E. (2004). Preparing teachers for popular music processes and practices. In C. Rodriguez (Ed.), Bridging the gap: Popular music and music education (pp. 159-174). Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Grant, C. (2013). First inversion: A rationale for implementing the 'flipped approach' in tertiary music courses [online]. Australian Journal of Music Education, No. 1, 2013: 3-12.

Green, L. (2008). Music, informal learning and the school; a new classroom pedagogy. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Green, L. (2014). Hear, Listen, Play!: How to Free Your Students' Aural, Improvisation, and Performance Skills. Oxford : Oxford University Press, USA.

Gulish, S. A. (2014). Lessons learned from java jam: An alternative music making event at the high school level (Order No. 3623166). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1549976313). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1549976313?accountid=14745

Hargreaves, D. J., & Marshall, N.A. (2003). Developing identities in music education. Music Education Research, 5(3), 263-274.

Heng Ngee Mok. (2014). Teaching Tip: The Flipped Classroom. Journal Of Information Systems Education, 25(1), 7-11.

Humphreys, J. T. (2004). Popular music in the American schools: What history tells us about the present and the future. In C. Rodriguez (Ed.), Bridging the gap: Popular music and music education (pp. 91-106). Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Jaffurs, S. (. (2004). The impact of informal music learning practices in the classroom, or, How I learned how to teach from a garage band. International Journal Of Music Education, 22(3), 189-200.

Jones, P. (2005). Music education and the knowledge economy: Developing creativity, strengthening communities. Arts Education Policy Review, 106(4), 5-12.

Jones, P. (2006). Returning music education to the mainstream: Reconnecting with the community. Visions of Research in Music Education, 7, (accessed October 29, 2013).

Jones, P. (2007). Developing strategic thinkers through music teacher education: A “best practice” for overcoming professional myopia and transforming music education. Arts Education Policy Review, 108(6), 3-10.

Kratus, J. (2009). Subverting the permanent curriculum in music education. Paper presented at the SMTE Symposium, Greensboro, NC.

Larson, L. (1997). The role of the musician in the 21st century: Rethinking the core. Plenary address at the National Association of Schools of Music National Convention. (accessed January 5, 2014).

Myers, D. (2009). Contemplating values in music teacher education: Can we achieve what we believe? Presentation at the SMTE Symposium, Greensboro, NC.

O'Flaherty, J., & Phillips, C. (2015). The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. The Internet And Higher Education, 2585-95. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.002

Regelski, Thomas A. (2013). Re-setting music education’s “default settings”. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education 12(1), 7–23.

Report of the Task Force on the Undergraduate Music Major (2014). Transforming Music Study from its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Undergraduate Preparation of Music Majors. The College Music Society.

Robinson, K. (2002). Teacher education for a new world of musics. In B. Reimer (Ed.) World musics and music education: Facing the issues (pp. 219-238). Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference.

Tobias, E. S. (2013). Toward Convergence: Adapting Music Education to Contemporary Society and Participatory Culture. Music Educators Journal, 99(4), 29-36. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1177/0027432113483318

Turino, T. (2008). The shifting locus of musical experience from performance to recording to data: Some implications for music education. Music Education Research International, 6, 38-55.

Westerlund, H. (2006). Garage rock bands: A future model for developing musical expertise?. International Journal Of Music Education, 24(2), 119-125. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1177/0255761406065472

Wilcox Brooks, A. (2014). Information literacy and the flipped classroom. Communications In Information Literacy, 8(2), 225-235.

Woody, R. H., & Parker, E. C. (2012). Encouraging participatory musicianship among university students. Research Studies In Music Education, 34(2), 189. doi: dx.doi.org/10.1177/1321103X12464857