Introduction

Providing students with practical working experience while they are completing their program requirements is a challenge for faculty in higher education. New technology and the rapid convergence of arts-related disciplines require that students are equipped with a strong knowledge base in their field as well as the ability to be adaptable to an environment that changes rapidly. Students must be prepared to think entrepreneurially, develop professional networks, and take strategic initiative to launch and maintain careers in arts related fields.

Simulation and gaming inspired pedagogy can provide students with opportunities that tie multiple components of curricula together as building blocks for practical experiences. With tactical guidance by faculty, students can navigate within “safe” environments where failure may provide the most robust learning opportunity.

This paper explores gaming pedagogy and simulation and their use in the Music Business Workshop, a one-week intensive, multi-course collaboration at Columbia College Chicago. This experience includes a simulation of the music business that contains a variety of game elements and serves as an example of the use of games as instructional tools.

Games and Gamification

Games can be built into curriculum online, integrated into classroom lessons, or even designed for entire classes. Games can also be a complete immersive experience. Gamification is commonly defined as the use of game elements and game design techniques in non-game contexts. Thus, game components can be implemented into pedagogy even if the class or lesson is not an entire game.

Gamification has been used in business to increase customer engagement and sales. Internally, games have increased productivity, motivated in repetitive job tasks, and improved crowd sourced project completion. Gamification has lead to behavior changes resulting in healthier lifestyles, better financial planning, and living in an ecologically more sustainable way. 1

Implementing game mechanics into learning is not a new concept. Games and learning have been associated for thousands of years although they did not reach a public prevalence until the mid twentieth century.2 The beginning of personal computing in the 1980’s was particularly a turning point in devising learning games along with the rise of the family software market.3 Currently, 74 percent of k-8 teachers use digital games in the classroom while 56 percent of parents believe that their children are positively affected by video games.4

Game Construction

Implementing game elements into curriculum can require substantial planning along with an understanding of how the elements enrich the learning outcomes. Games create a framework for creativity within constructed boundaries. Gamification can be planned by first defining the objective of the game elements and how they relate to learning objectives and then analyzing the knowledge base and overall background of the students or players. The next step is to target specific desired behaviors such as better engagement and comprehension of course material. All goals are being achieved while maintaining a key motivating factor in game play--fun. Finally, the appropriate and specific tools and elements can be implemented.5

Games typically include three elements. The first is a feedback loop to show how a participant is progressing or failing. The second is interaction with others in teams and the class overall. Finally and as previously emphasized, games by definition should be fun. Other elements that can be implemented are simulations and role playing to solve problems. These activities can help students view other perspectives within a scenario.

A typical cycle for game play is to initiate a challenge, provide an achievement to this challenge, have a new progressive challenge, and then repeat these steps. As challenges are conquered, dopamine is released in the player's system, making the experience physically pleasurable and motivating.6

The arch of activity often seen in games is first onboarding players (students), which means having them step into the game easily and then motivating them to continue. Then players progress slowly enough where they do not become confused or frustrated but fast enough to avoid boredom. Finally the player sees an end point where he or she can master the game. The game can strike this ongoing balance to provide motivation to continue toward mastery, or the win state.7

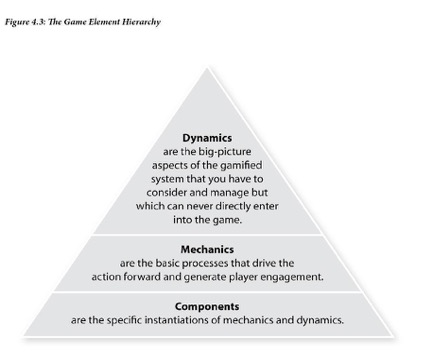

Game elements can fall within three categorizes, ranging from broader objectives to the more specific pieces. Please refer to Figure 1 for the hierarchical depiction of game dynamics, mechanics, and components.

Game Dynamics

As portrayed in Figure 1, game dynamics can be thought of as the broader conditions in the creation of a game. One dynamic can be constraints such as artificial boundaries, time constraints, and “educated” choices that the player must make to motivate him or her through a sense of urgency. Emotion is a second dynamic, whereby the game initiates emotional responses that can further motivate players to try harder. Narrative is a third dynamic and refers to a player’s experiences making sense in the larger context of the game. A gamified system’s narrative can create coherent and consistent smaller pieces of the experience that prove logical within the overall story. Another dynamic is progression, whereby the player feels a sense of accomplishment and moving forward. Repeating the similar steps without challenge at a higher level often leads to boredom and abandonment. A final dynamic to consider is relationships. Popularity in gaming increasingly comes from social interaction of the players and often their cooperating to achieve a common goal. Even if a player were to engage with the game individually, he or she will often prefer to communicate and share experiences and accomplishments.8

Figure 1: Game Element Hierarchy (For the Win)

Game Mechanics and Components

Several key mechanics in games include challenging the player, taking turns, providing feedback and rewards, and implementing an element of chance and luck. Mechanics can consist of the player cooperating with others and/or competing with others. Other key mechanics include the player acquiring resources, undergoing transactions, and winning.9

The three main components in gamification are points or virtual currency, leaderboards that post top ranked players, and badges that are awards for statuses and accomplishments. Other key componentry includes achievements, player avatars, collections, combat, content unlocking, gifting, levels, quests, teams, and virtual goods.10

Simulation vs. Gaming

The term “simulation” is often used interchangeably with the term “game” and the difference between the two is not broadly understood. According to Marc Prensky, simulations are not in and of themselves games. Simulations become games when they contain game elements. The use of games versus simulations in higher education is dependent on many factors including the goals of the instructor, the needs of the students, and the context of the experience. Teachers must consider a number of factors including but not limited to the type of material, the amount of time available for the activity, the physical environment, and the number of participants. People have learned to drive and fly in simulators for decades, but simulations are not always games because they do not always implement key motivational game elements like the inclusion of fun or a points system.11

Motivating Factors in Games

Motivational psychologists purport that people are motivated intrinsically and extrinsically. Intrinsic motivation pertains to doing something because it is inherently fun and the participants want to excel.12 Learning does not have to be unpleasant, and fun can be the pedagogically most effective path to motivating learning. Extrinsic motivation is motivation based on external rewards. According to researcher Gabe Zichermann, there are four extrinsically motivating factors in games. The highest ranked motivational dynamic is status. Players are the most motivated by leveling up over others. The second most important factor is receiving access to something that the player could not previously obtain. The third dynamic is power within the game itself and over others playing. Finally, the least motivating aspect is receiving prizes, gifts, and money. To some people this ranking is counterintuitive, and some dispute its validity. If it is true, however, it is encouraging that the most expensive motivating factors of tangible prizes are of the least importance.13

Negative results can occur in building gamified pedagogy. Gamification, which emphasizes extrinsic motivators, could potentially overshadow intrinsic motivators. Building extrinsic, tangible rewards into the curriculum could potentially cause students to focus on those and thus replace the intrinsic motivation of fun and the knowledge gained as inherently gratifying.14 Gamification can also be counter-motivational. If a points system (leaderboard ranking system for example) makes the experience too competitive or is perceived as too much pressure for the outcome, it may result in the experience being less rewarding for the student.15

Millennial Impact

Games can be effective for teaching Millennials, otherwise known as Generation Y. This is the generation currently of traditional college age or those born in the 1980’s and 1990’s.16 Millennials can be identified by what motivates them. Progression is apparent as learning occurs in small pieces. Games can provide a quick if not immediate loop of feedback, and a game environment can provide relatable, big picture relevancy. All of these conditions are thought to better motivate Millennials.17 Courses and programs can seem overwhelming regarding what is to be accomplished, and the overarching concepts may seem abstract. Millennials multitask significantly more than previous generations and are engaged in compact and interactive information like social media.18 They are much more extrinsically motivated than previous generations, and they also seek relevance. Gamification can provide students realistic simulations, quickly scaffolding a feedback loop and progression in a familiar and structured context. Prompt feedback occurs through scoring, social sharing, badges, ranking, and group collaboration.19 This discussion provides the background and impetus for a dynamic, interdisciplinary workshop.

The Music Industry Immersion and The Music Business Workshop

The Music Industry Immersion (MII) is a set of three classes offered at Columbia College Chicago during the J-Term (January session between fall and spring semesters) that was inspired by the International Band and Business Camp offered by Popakademie University, Mannheim Germany and the MuZone Partners. The MII includes three courses offered simultaneously: the Music Business Workshop, The Music Workshop, and The Recording Workshop. Columbia College’s departments of Business and Entrepreneurship, Music and Audio Arts, and Acoustics offer these courses respectively. They are offered in the same timeframe to allow for collaboration of students across projects.

Students in the Music Workshop are formed into bands or ensembles to write original music and prepare an original performance of their music. The Audio Arts and Acoustics students record the original material and work with producers to create professional quality recordings and engineer a professional sounding live showcase of the music. Students in the Music Business Workshop are engaged in a simulation game of the music industry and are also required to prepare for the release of the original recordings created in addition to marketing and promoting a final live showcase. These courses are completed over five days with students meeting for twelve hours each day and earning three (3) credits for the course in which they are enrolled. For the purpose of this paper, the focus will be on the simulation portion of the Music Business Workshop (MBW), which occurs over 36 hours of the course.

The Music Business Workshop Simulation Overview

The MBW involves a situational simulation and includes role-playing to allow students to consider different options and make decisions.20 The simulation is a true collaborative experience with students attempting to reach common goals while sharing tools and activities.21 For the simulation portion of the Music Business Workshop, students are divided into teams that must prepare a plan to launch a new music business venture. All ventures begin as some form of record company with a goal to sign artists to record deals and to release music in some form. Students are presented with an imaginary pool of money controlled by investors (faculty) for which they are competing. They prepare a formal business plan that includes details of their proposed organization. This plan consists of an organizational structure, business activities, value proposition, target customer segments, sources of income, planned partnerships, explanation of costs, sources of revenue, and methods of distribution. The business plan is then presented to faculty who take on the role of investors listening to the prepared pitches of each team. This “kick-off” assignment or initial challenge allows students to begin working closely with their team and to establish the basis for which they will operate as a music business throughout the simulation. Students are free to create a business of their choice with only the constraint of initially functioning as a record company that must sign recording artists with whom they believe to be viable and that fit the strategy of their company. This caveat is a significant structure within the simulation.

Creating the Simulation Environment

A base set of assumptions is introduced into the simulation to establish the environment within which the students and faculty will be working. These assumptions provide some constraints that help to frame the simulation for the students. For example, students are presented with established expenditures for items they will likely require to start and run their businesses. As an illustration, a common practice in the music industry is for companies to hire an independent promoter. For this reason the simulation assumptions include tiered costs for hiring an outside promoter based on the level and duration of service of the promoter. The students, however, must decide to use an outside promoter for their business activities and at what level. Additionally, students will have a clear understanding of the amounts of revenue they can generate from certain activities, such as the sale of a physical album. Because the scope of activities within the simulation may change and develop, new assumptions are often introduced by the faculty as activities progress.

To facilitate efficient transactions and increase the number of opportunities for students to learn, templates are used throughout the simulation for deal-making and reporting purposes. These provide further constraints for students. They will have access to a recording contract template, for example, in order to establish clear terms for the deal they will have to negotiate with a faculty member who will be in the role of an artist’s manager. Other examples of templates used in the simulation are revenue reporting, accounting, and tour itineraries to name a few. Students are not limited to deals that exist within the provided templates. If students desire to engage in a business activity that will go beyond the scope of an existing template format, they will work with faculty to develop a new agreement or contract. This however will place the faculty member into the role of an attorney who will then charge the student a fee for his or her services. Because there are many transactional opportunities for students throughout the simulation and many are often repeated, students and faculty become aware of student learning and growth as the simulation progresses. It is not uncommon for a student company in the simulation to sign agreements with many artists, which means they will have to negotiate terms repeatedly. Of course, the objective is that hopefully they improve their position with each one.

The simulation is driven by two key components, the time clock and faculty engagement. The simulation timeframe within which students are working is accelerated. Every hour is a month during the simulation meaning every twelve hours is one year. This accelerated time adds stress and urgency and requires students to be conscious of their time when working, meeting deadlines, making appointments, and fulfilling contractual obligations. The roles and engagement of faculty emerge as essential components.

The Role of Faculty

Faculty members in the Music Business Workshop perform a number of roles to engage students and to help guide them through the simulation. They initially function in the role of investors who will ultimately be majority shareholders of each company. They also take on roles as determined by the needs of the simulation as it progresses. For example, faculty members may be attorneys, artists, artist managers or a banker, sponsor, fan, producer, government official, etc. Faculty will mentor each team and regularly step out of their roles within the simulation to guide students or answer questions. Because faculty members act within these different roles, students must confirm what role faculty may be assuming should it not be apparent. Also, students can ask to “speak with a faculty member” at any time if they need guidance.

Significant faculty engagement is required to establish and maintain progression in the simulation. A key task for faculty is to manage the simulation to ensure buy-in from the students, facilitate learning through feedback, promote continued engagement, and challenge students to be creative with their business endeavor. Working from a central office the faculty are also the ones who provide the students with evolving storylines and scenarios to present new challenges, force students to work outside their comfort zone, and to create increasingly complex interaction. This is done primarily by presenting students with information that may or may not have an impact on the operation of their business. Students regularly receive information from faculty as shareholders, other persons, or business entities. To reward and challenge students and to facilitate progression through the simulation, information is passed on to them in forms identified by Kienda Hoji as good news, bad news, or dilemmas. They will then have to make decisions on the information presented and navigate to better their company’s position.22

In the Music Business Workshop, faculty members also produce an online publication called Pitchspork News where information is distributed about all companies’ successes or failures. Pitchspork also includes new opportunities, changes in industry environment, new assumptions, information about artists, or any news that may advance the simulation and be useful to the students. In the most recent offering of this simulation class, one of the students who headed her team organization as CEO was fired by the majority shareholders for allowing the company to go an entire year without releasing any product. This situation meant that the company had zero revenue for the year. It was a very profound learning moment for the student and her team; one they will not likely forget, and one better learned in the classroom than in the real world. Without all of the details of the situation, information about the firing was published in Pitchspork News. Once the tears from the experience dried, the student was quickly picked up by another student company and soon managed to find herself in a leadership role in that new company.

Student teams regularly scheduled meetings with shareholders annually (or each day within the simulation) to report their progress as a company and present the faculty shareholders with a plan for the upcoming year. This process establishes a nice narrative for the students who can easily understand how their activities and engagement in the simulation connect and make sense as an experience for them. Additionally, at the end of the simulation, there is a reflection and debriefing23 meeting with the faculty.

Motivating Students

Extrinsic motivators such as status, access, and power are implemented throughout the Music Business Workshop. Students achieve status via the successes of their companies. These companies are often competing with others to sign recording agreements with particular artists perceived to be high profile within the simulation. A successful deal with one of these artists is a measure of status within the simulation. Faculty members also provide a daily leaderboard that ranks companies by a particular form of assessment. The criteria are not revealed to students until the leaderboard is posted. For example, a ranking might be for the most engaged company or the most music released within a simulation year. Access is represented by the relationships students develop through the course of the simulation with various entities within the simulation. As an example, students have the opportunity to build relationships with sponsor companies, booking agents, and just about any entity they can envision having a business opportunity for their company. Acting in these roles, faculty members have the ability to reward or allow these relationships to translate into positive results for the student companies or for individual players. Students have several opportunities to gain power within the simulation. Students assume different leadership roles within their organizations, have access to important information they can leverage to increase their company's success, and take actions that can result in increased revenue for their organizations.

Surprisingly, the grade that a student receives for their participation in the MBW seems to be of little importance to them as they progress through the simulation portion of the class. Students rarely bring up the question of a grade for performance during the simulation as they are extremely focused on the content of the simulation and are aware of the learning that is taking place.

Learning Outcomes

The Music Business Workshop provides students with the opportunity to learn and apply basic, intermediate, and advanced concepts previously learned in more traditional courses. Students examine music industry challenges and strategically develop solutions. Students plan and build a music business and then implement a marketing campaign for hypothetical music releases and live performances.

Students must react to unknown situation and improvise responses. Students practice leadership, innovation, and creativity through unforeseen challenges.24 The arts, entertainment, and media industries are rapidly evolving particularly due to technologies impact on content production, distribution, and communication. Succeeding as managers and entrepreneurs in these industries requires good leadership by properly managing the reaction of oneself and empathetically reacting to opinions of others.25

The simulation portion of the Music Business Workshop provides opportunities for students to be challenged as leaders and team members. The simulation plunges students into a variety of situations that require them to recall information they have learned, seek out unknown information, and react in a manner that will strategically better their position within the simulation. The use of their collective knowledge and experience along with the choices they make in applying that knowledge determines their success or failure. An example is when faculty assume the role of artist management or attorney to negotiate a contractual agreement between the student company and an artist.

Scenarios Contributing to Learning Outcomes

The most common agreement in this simulation is a recording deal. Students need to recall their knowledge of entertainment law, music publishing, and traditional terms of these types of agreements. They will need to consider the position of their company and the status of the artist with whom they are trying to enter into the agreement. The terms to which students agree will ultimately determine their success or failure in that venture. If they agree to pay the artist an advance of funds that cannot be recouped from music sales, they will realize a loss for their company. If they agree to a short-term agreement without appropriate options to renew, they could lose a successful artist or an artist in whom they have invested to another company. This new company may realize the benefits of the artist’s development. Conversely, a strong agreement could result in a successful and profitable relationship with an artist.

The simulation requires students to work closely in teams under intense conditions over long periods of time, which can sometimes be stressful and fatiguing. The pace at which they work, required decision making, and the competitive nature of the simulation provide students the opportunity to experience changes in their emotional state and gain an understanding of the ways in which they deal with pressure and fatigue. They also witness fellow students experience with these challenges and are often required to react to these situations. The manner in which students manage success, failure, and uncertain situations all becomes apparent throughout the course of the simulation.

Conclusion

Building entire immersive experiences online can be cost and time prohibitive, and simulations in the classroom can be very complex as well. Instead of building entire classes comprised of games, educators can implement select and appropriate elements.

When constructed appropriately, the use of game elements in the classroom can be very effective in achieving goals established by the instructor. Games can grab attention and keep students actively engaged in the lesson by providing a context for the central content. Games offer the development of a variety of skills beyond just exposure to the new content being presented. Such skills include critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork. The use of games can provide practice opportunity and immediate feedback. Additionally, games provide the opportunity for students to develop an emotional connection to the content. This connection occurs because they are learning from a variety of sensory experiences and stimuli including engaging in conversations, reading information, and acting or role-playing.26

Although games and simulations have been used in education for many years, it would not be surprising to see an increase in their use in higher education going forward. The continued penetration of digital devices within society makes access to gaming easier. As children become more accustomed to the use of games as a tool for learning, its acceptance and prevalence in higher education is probable.

Notes

1 Werbach and Dan Hunter, “For the Win,” 16-17.

2 Kahne, “History of Games and Learning,” 1.

3 Ibid.

4 “Video game stats,” accessed July 10, 2015.

5 Werbach and Hunter, 66.

6 Ibid., 74.

7 Ibid.

8 Werbach and Hunter, “The Gamification Toolkit,” 14-21.

9 Ibid., 22-25.

10 Ibid., 26.

11 Prensky, “Simulations: Are They Games?” 2.

12 Zichermann, “Gamification.”

13 Pink, “The Surprisinig Truth. . . .” 15.

14 Werbach and Hunter, 47-48.

15 Werbach and Hunter, 54.

16 “Millennial,” Dictionary.com.

17 Goudreau, “7 Surprising Ways to Motivate Millennials.”

18 Miller, “Why You Should Be Hiring…”

19 Knaidele, “Gamification,” last modified September 2, 2014.

20 Lunce, “Simulations,” 38.

21 Leemkuil, et al., “Simulation & Gaming,” 104.

22 Hoji, “Mu Zone Documentary.”

23 Leemkuil, et al., “Simulation & Gaming.

24 Smith, “Gamification.”

25 Gleeson and Crace, “The Use of Emotional Intelligence”

26 Stathakis, “Reasons to Play. . . ,” Education World.