Charles Wakefield Cadman is best known today for his popular-style ballads which achieved a remarkable commercial success in the early decades of the twentieth century. What is less well known is that Cadman considered his primary talent to be in the field of opera and that he composed five works that can be so categorized. Two of these were produced by major United States opera companies during Cadman's lifetime: The Robin Woman (Shanewis) by the Metropolitan Opera Company in the 1918 and 1919 seasons, and A Witch of Salem by the Chicago Civic Opera Company in 1926. Another, The Willow Tree, is distinguished as the first opera composed expressly for radio performance; this miniature (24 minutes) was broadcast by the NBC network in 1932. Another short opera, The Garden of Mystery, was performed by a cast of singers assembled for the purpose in Carnegie Hall in 1925. Only his first and longest opera, Daoma, remained both unperformed and unpublished. The librettos of all five operas, like most of his song texts, were written by Nelle Richmond Eberhart (1871-1944), his friend and confidante for over 40 years.1

Cadman's determination to compose opera began when he was 14 years old. His musical experience theretofore had consisted of family singing around the piano and a few piano lessons from local teachers, but in 1896 he attended a performance of Reginald DeKoven's Robin Hood which was presented in Pittsburgh's Alvin Theatre. He was deeply impressed:

It was an unconscious love of music, however, until I heard my first opera, DeKoven's "Robin Hood," which was produced in Pittsburgh when I was fourteen. I had been taking a few lessons and something about the advance posters of the performance appealed to me. The admittance cost seemed prohibitive, but bit by bit, I saved up the sum for a good seat. I didn't want to miss anything.

I'll never forget how carefully I dressed on the eventful evening, nor how early I arrived, nor how high up in "peanut heaven" was my seat (in spite of the price I had paid). But more than all else I remember the joy that came to me as the musical story unfolded itself to my eyes and ears. From the time I left the theater I never wavered in my determination to write operas of my own, to make music that my own countrymen would love and understand.2

During the next few years he composed a few songs which met with little success and then in 1899-1901 he tried his hand at operetta. In collaboration with a cousin, Avery Holmes Hassler, a newspaperman living in Indianapolis, he composed The King of Molola.3 This was followed by Cubanita, with a libretto based on the recent Cuban struggle for independence. Excerpts from Cubanita enjoyed a modest success in a performance in the Duquesne Gardens in Pittsburgh, but Cadman was never able to bring either operetta to a full production.4 Attempts to secure financial backing for a tour of these works failed, as did his efforts through a New York agency to interest producers of opera and operetta, including Dillingham and Savage, to take them.5 None of these scores seems to have survived, perhaps because Cadman was embarrassed by these early attempts. Some years later he expressed the desire that these "salad day" efforts remain unpublished, although at least one number, a chorus, "Woodland Song," was used independently.6

Cadman's first commercial success came in 1909 with Four American Indian Songs, Opus 45.7 These songs, based on Omaha and Iroquois melodies and composed in 1907-08, were Cadman's first essay in composition with Indian melodies. They enjoyed a remarkable success which was launched by performances by the distinguished American soprano Lillian Nordica, and they assured Cadman's permanent identification with the so-called "Indianist" group of composers which flourished in the first two decades of this century.

The growth of this Indianist movement had been fostered by the proliferation of ethnological studies of Indian culture, including music, in the two decades spanning the turn of the century. Monographs, some of them devoted entirely to music, by Alice Cunningham Fletcher, Francis La Flesche, John Comfort Fillmore, Frederick R. Burton, Natalie Curtis, Frances Densmore and others, stimulated the imagination of a small number of American composers intent on creating a national music. By 1910 many Indian-melody-based compositions by Carlos Troyer (1837-1920), Harvey Worthington Loomis (1865-1930), Charles Sanford Skilton (1868-1941), and Arthur Farwell (1872-1952), to name but a few of the most important composers, had found their way into print, and a grand opera based on Indian themes (Arthur Nevin's Poia, 1910) had realized public performance, although in Germany rather than in the United States.

Cadman joined the Indianist movement as it approached its height, after the publications of Farwell and others had aroused public interest in "Indian" compositions. Farwell's eschewal of the musical language of German Romanticism and his somewhat unconventional style stood in the way of acceptance of his works by a wide audience, but Cadman's facile style ensured his Four American Indian Songs almost immediate popularity. All of Cadman's remaining major Indian compositions (including two operas) were composed during the next eleven years: "To a Vanishing Race" (from Three Moods, 1909); Daoma, later retitled The Land of Misty Water, and then Ramala (1912); From Wigwam and Tepee (1914); Thunderbird (incidental musical and orchestral suite, 1917); The Robin Woman (1918); and The Sunset Trail (first version, 1920).

Cadman's first opera, Daoma (DA-o-ma), was conceived late in 1908 during the final preparations for his first "Indian Music Talk," a lecture and recital of Indian music and Indian-based compositions that he continued to present, with minor modifications, over the next 25 years. During the course of his preparations he consulted with Alice Cunningham Fletcher (1838-1923) and Francis La Flesche (1857-1932), both recognized authorities on music of American Indians.8 La Flesche had been pleased by Cadman's treatment of Indian melodies in Four American Indian Songs, and it was he who suggested that Cadman, in collaboration with Eberhart, should compose an opera based on a traditional Siouan legend which he would provide. Cadman's acceptance was immediate.9 His enthusiasm for the project could only have been heightened by the announcement at that time of a $10,000 prize for the "best American Opera"—ample demonstration for him of the financial as well as artistic potential for opera composition.10

Eberhart began writing the libretto in June 1909. With both residing in Pittsburgh, she and Cadman were able to work closely in planning the opera. They corresponded frequently with La Flesche and their collaboration appears to have been generally harmonious. From time to time La Flesche objected to what he considered unrealistic dialogue, extraneous airs that he felt interrupted the continuity of the story, or lack of adequate development of characters, but in every case he seems to have acceded finally to the judgment of his collaborators.11

In the summer of 1909 Cadman began to collect and catalog Indian melodies for possible use in the opera, but before he began its actual composition, he made his first excursion to an Indian reservation. He joined La Flesche at the Omaha reservation at Walthill, Nebraska in early August 1909 where he remained for several weeks, assisting La Flesche in making cylinder phonograph recordings and transcribing the music as well as photographing Indian ceremonies.12 They also worked together on the libretto and selected more melodies for use in the opera.13

The composition of Daoma was begun on September 14, 1909.14 The first act was completed by April 1910, and about one-half of the second act by midsummer, all in piano-vocal score with the instrumentation completed only in occasional passages.15 Work on the opera was suspended in late summer when Cadman spent approximately six weeks as a guest of the Kunits family at their villa in Prein, Austria.

Always in a precarious state of health, he suffered an almost total physical collapse upon returning to Pittsburgh, and all work on Daoma was put aside until he had recovered sufficiently the following April. His recovery was speeded by a stay at the Presbyterian Sanatorium in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the expenses being covered by the receipts of a testimonial concert arranged by his Pittsburgh friends and admirers. Among the participants in this concert was Boston Opera Company soprano Alice Nielsen, whose services were provided by the company manager, Henry Russell.16 Progress on Daoma then continued steadily, interrupted only by occasional tours to present the Indian Music Talk and by a move to Denver in July 1911. The piano-vocal score was completed on March 9, 1912,17 the full orchestral score on August 26 the same year,18 and the fair copy of the full score was finished in October.19 It was sent immediately to Henry Russell who, at Alice Nielsen's request, had agreed to consider the score for possible production by the Boston Opera Company. But Russell rejected the opera. He gave as his reason the "dangerously untheatric" nature of the story. However, he praised the poetry and the music and sent the score to the White-Smith Music Publishing Company (Cadman's principal publisher) who also turned it down. Still confident of the merits of the opera, Cadman renamed it The Land of the Misty Water, hoping that the similarity of this title to his successful song "Land of the Sky-blue Water" would prove beneficial, and he submitted it in 1914 to Giorgio Polacco, a conductor at the Metropolitan Opera House. Polacco also rejected it.20

In a further attempt to promote the opera, Cadman engaged Norman Bel Geddes to design and execute watercolor drawings of costumes and stage settings, and a portable miniature stage. In exchange Cadman agreed to compose incidental music for Bel Geddes' Indian drama, Thunderbird.21 I do not know whether Cadman ever used these drawings and settings, or whether he submitted them with the opera to the American opera competition sponsored by the National Federation of Music Clubs in Los Angeles in 1915. The $10,000 prize was awarded to Horatio Parker's Fairyland. Cadman, deeply disappointed, set his opera aside, and did not complete its revisions until more than 20 years later.22

The libretto of Daoma, like all the Eberhart librettos, is extremely simple. There are no complicating subplots and the number of characters is small. These include Aedeta (baritone) and Nemaha (tenor), young men of a Siouan tribe; Daoma (mezzo-soprano), a young Siouan woman; Megena (soprano), cousin of Daoma; Taene (contralto), mother of Daoma; Obeska (bass), tribal chief; three minor parts—a sentinel, a scout, and the warrior Kaela (tenor, baritone, baritone); and a mixed chorus that variously represents spirit voices and members of the Siouan and an enemy Pawnee tribe.23

The story, set in the early years of the nineteenth century, begins with the taking of a vow of eternal friendship by Nemaha and Aedeta upon their discovery that they both love the maiden Daoma. In Scene 2 Daoma, unable to choose between the two men, relegates her decision to a game of chance (catching antelope hooves on a pin): Aedeta is chosen. Meanwhile Daoma is chided for her method of choice by Taene and by Megena, the latter actually relieved by Daoma's choice, for she loves Nemaha. The scene concludes with a Siouan war party (including Aedeta and Nemaha) departing to confront the enemy tribe. Daoma follows them a short time later.

The second act begins with Daoma, on horseback, approaching the war party camp. First Nemaha then Aedeta go to meet her. She reveals her choice and, contrary to tribal custom, the chief Obeska, recognizing her extraordinary devotion to her love, performs the brief wedding ceremony—just before the men engage the enemy offstage. Scene 2 begins as the warrior Kaela, wounded, returns with news that the Sioux have been defeated. Soon Nemaha also returns declaring that Aedeta has been slain, and offers his own love to Daoma, urging her to forget Aedeta. She repulses him, demanding in vain that he take her to the place where Aedeta died. Scene 3 is devoted to her search of the battlefield where she finds Aedeta's bow, its string cut. She then realizes that he is alive and has been taken captive by the enemy, but she does not suspect that the bow string had been cut by Nemaha.

In the third and last act Daoma steals into the enemy camp during the victory celebration. She finds Aedeta, releases him, and they escape. The final scene is set in the Siouan camp as the lovers return to reveal the treachery of Nemaha, who, amid cries of "Kill him!" from the tribe and pleas for mercy from Megena, Daoma, and Aedeta, suddenly appears on stage and commits suicide by stabbing himself. The opera concludes with a brief epilogue in which Megena proclaims her sorrow. Thus Cadman and Eberhart established in Daoma a theme that was to dominate four of their five operas: the swift and violent punishment of deceit or betrayal of friendship for the sake of love.

Daoma is entirely conventional in form. It begins with a short prélude that exposes several of the principal melodic motives of the opera, and continues with recitative that varies from perfunctory declamation to an arioso style as it conveys action, conversation and reflective monologue. At appropriate moments, airs are introduced to allow reflection upon the situation and—perhaps more important to Cadman—to allow him to exercise his highly prized and often vaunted gift of melody. The chorus, used frequently, serves primarily in a scenic capacity, although in the finale of Act III it becomes involved to a degree in the dénouement of the drama. The relative paucity of airs in Daoma is surprising, particularly in view of Cadman's penchant for lyrical, sentimental song: in this opera of approximately two and one-half hours' duration there are only ten airs (some very brief), four duets, and a brief trio. Ten of these are concentrated in the pastoral Act I, four in the first scene of Act II (the marriage scene), and one in the second scene (the pivotal point of the opera where Nemaha's treachery occurs). The remainder of the dialogue of the opera, with its ever-increasing emotional pitch and violence, is conveyed entirely in recitative.

Daoma was intended by Cadman to be purely Indian, making use of Indian melodies as a basis for the music and dealing solely with Indian culture, settings, and characters untouched by the white man. In an attempt to emphasize the exotic nature of the subject material (and despite the composer's misgivings) Eberhart chose to use archaic forms of address ("thee," "thou," "thine") and construction ("Friends shall we go into battle." and "What means this design?"), the latter mixed quite inconsistently with modern usage.

Among Cadman's sources of Indian melodies were three printed collections, all by Alice Cunningham Fletcher: Indian Story and Song;24 "A Study of Omaha Indian Music," with melodies transcribed and harmonized by John Comfort Fillmore;25 and "The Hako: A Pawnee Ceremony," with melodies transcribed by Edwin S. Tracy.26 He also employed a number of melodies he had collected during his visit to the Omaha reservation in 1909. However, his principal source seems to have been La Flesche, who responded to frequent requests for additional melodies as the opera progressed. One source was denied: his request for permission to use melodies he and La Flesche had collected for a forthcoming report of the Bureau of American Ethonology was refused by F.W. Hodges, Bureau ethnologist, much to the composer's indignation.27 For the rest Cadman relied upon his own invention.

The style of the music of Daoma is similar to that of his successful sentimental ballads—best represented by Four American Indian Songs. His basic technique for composing with Indian melodies (he called it "idealization") was described in an article he wrote for the third issue of the Musical Quarterly (July 1915) at the request of its editor, Oscar Sonneck.28 The process began with careful selection of Indian melodies, for he found that only about one-fifth of the melodies he examined were "suitable for harmonic investment," i.e., conforming to either major or minor scale forms and amenable to a conventional harmonization in the style of Cadman's sentimental ballads. Some of the harmonizations were simple, as when he drew his melodies from Fletcher's monograph on Omaha music and simply retained Fillmore's harmonization; but often his harmonizations were more complex, employing considerable chromaticism and frequent abrupt key changes, usually third-related. In true Romantic fashion, he preferred keys with many sharps or flats: five, six, and even seven are very frequent in Daoma, their difficulty for orchestral players notwithstanding. The recitative passages, many based on Indian melodies, were produced in a similar fashion, but all too often the effect is awkward and contrived as he attempted through imitation of Italian or French models to work in a technique that was alien to his lyrical bent.

Identification of Indian melodies in Daoma is often problematical, complicated by the fact that Cadman frequently paraphrased them freely, extracted motives from them, or composed new melodies that achieve an "Indian" quality through the use of pentatonic melodic figures, syncopated rhythms, and "drum-beat" accompaniments. These traits were to be found in so much of Cadman's music of this period that his name became irrevocably associated with Indianism—an association he later came to rue.

He used a system of leitmotivs to represent characters and ideas in Daoma. These were presented in a table of "Themes or Motives Found in the Opera" which was added to the piano-vocal score prepared in 1914 for submission to the opera competition sponsored by the National Federation of Music Clubs.29 Cadman's use of these motives is conventional: they underscore the actual entrance or presence of a character or idea, or suggest involvement in situations when it is neither present nor overtly involved. They are rarely sung, rather being confined to the orchestral accompaniment or independent orchestral numbers. He identified twelve motives:

Daoma's Theme

Aedeta's Theme

Nemaha's Theme (used in many forms)

Obeska's Theme

Darkness or Evil Theme

Treachery Motive

Friendship Vow Theme

Aedeta's and Nemaha's Love for Daoma

A Love Theme in Act I

War Motive distinct from battle music of Act II

Hope Theme

Destiny Motive

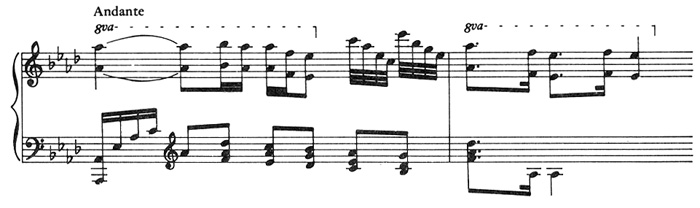

Daoma's motive appears infrequently, perhaps because its lyrical nature precluded its easy incorporation into the orchestral texture (Ex. 1).

Ex. 1. Daoma's Theme.30

It is introduced at the first mention of her name (Act I, Scene 1), and recurs in combination with Aedeta's motive in the marriage scene (Act II, Scene 1). The motives of Aedeta and Nemaha, on the other hand, are more elemental in nature (see Ex. 2, d and b) and they pervade the opera, appearing in the Act I prélude and in every scene thereafter, including that of the women in Act I, Scene 2.

Ex. 2. Daoma, Act II, Scene 1, prélude, p. 1.31

The motive of Obeska appears only when the old chief is active: in the war party scenes (Act II, Scenes 1 and 2) and as he greets the returning Daoma and Aedeta (Act III, Scene 2). The abstract motives are also used sparingly. For example, the "Treachery Motive" appears first in the accompaniment to Nemaha's pledge of friendship to Aedeta which is sung "with feigned emotion and fervor" (Act I, Scene 1), then as Nemaha tells Daoma that Aedeta is dead (Act II, Scene 2), again when Aedeta reveals the perfidy of Nemaha (Act III, Scene 2), and finally in abbreviated rhythmic form in the last four measures of the opera.

The first scene of Act II is typical of Cadman's method. It begins with a brief orchestral prélude of 27 measures, based on five melodic/rhythmic elements used simultaneously (Ex. 2): (a) a reminiscence of the opening motive of the "Indian love-call" that begins the Act I prélude;32 (b) a fanfare-like motive representing the aggressive Nemaha, also from the Act I prélude; (c) a literal quotation of the melody of the first eight measures of Fillmore's transcription of an Omaha parade song (No. 25, "Tokalo Wa-an") which Fletcher describes as "well suited to the prancing step of a spirited charger;"33 (d) the motive representing more serene Aedeta, also from the Act I prélude; and (e) a typical Indian drum beat rhythm. The curtain then rises to reveal a Siouan war camp and a chorus of warriors chanting a prayer (No. 12, "Hae-thu-ska Wa-an") as they begin the pipe ceremony.34 The Indian melody, its text, and its accompanying cross-rhythm drum beat are quoted almost exactly, in the original key (Ex. 3); a descending chromatic line is added in the bassoons.

Ex. 3. Daoma, Act II, Scene 1, Chorus, "Wakonda," p. 10.

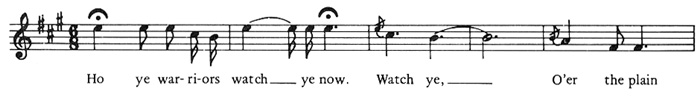

Soon a sentinel alerts the camp to the approach of an unidentified woman (Daoma) on horseback (Ex. 4).

Ex. 4. Daoma, Act II, Scene 1, recitative, "Ho ye warriors," pp. 18-19.

The melody of this recitative is a literal quotation of a call to a ceremonial dance (No. 5, "Hu-bae Wa-an").35 Except for the sustained e' in the bassoons in the first few bars, it is unaccompanied—one of the few such passages in the opera. It is extended slightly by repetition of the last three words of the text an octave higher, and a repetition of the first phrase of text and music. This scene then continues with 127 measures of recitative-style dialogue among the warriors, some of it based on melodies drawn from Fletcher's monograph but most of it apparently newly-composed. Frequently Cadman's newly-composed material sounds "Indian" because of its pentatonic structure and use of inverted-dotting; at other times it lapses into a stereotyped recitative style with frequent repeated notes and octave-leap cadences. Whenever possible, Cadman chose melodies whose original text and/or function corresponded to the particular moment in the opera, as in the passage sung by Aedeta and Nemaha in response to the report of the sentinel. This is based on a melody whose function was to greet a messenger of peace. More frequently, however, Cadman had to compromise this principle and use either irrelevant or newly-composed material when no appropriate model could be found.

Two of Daoma's three solo airs occur in this scene. The first, "I Have Come Here Alone, " is only 18 measures long, perhaps too brief to be considered an air in its own right. It is based on Fletcher's transcription of a song of lament for slain warriors (No. 16, "Hae-thu-ska Wa-an").36 Cadman simplified the alternating  -

- meter and the dotted rhythms of the original and transposed it up a half-step to E Major. He used only the first three measures of this melody as a point of departure, composing new material to complete the air while preserving the pentatonic quality of the lament, and then substituting for Fillmore's diatonic harmonization a chromatic one, including an enharmonic modulation to the key of F Major in the last six measures.

meter and the dotted rhythms of the original and transposed it up a half-step to E Major. He used only the first three measures of this melody as a point of departure, composing new material to complete the air while preserving the pentatonic quality of the lament, and then substituting for Fillmore's diatonic harmonization a chromatic one, including an enharmonic modulation to the key of F Major in the last six measures.

After a passage in recitative which does not appear to have been based on Indian melody, but which does use in its accompaniment the leading motives of the two warriors, Daoma sings her principal air, "I Have Followed My Love" (Ex. 5).

Ex. 5. Daoma, Act II, Scene 1, air, "I Have Followed My Love," pp. 66-67.

While I have been unable to identify the source of this melody, a letter written by Eberhart to La Flesche indicates that it was based on one of 19 Omaha melodies sent to Cadman by La Flesche.37 It is typical of the Cadman/Eberhart songs in its use of inverted dotting coupled with downward melodic inflections, chromatic harmonization, and highly sentimental text; it was a style of song that Cadman referred to as his "concert ballad type." This was the only song in the opera that Cadman ever attempted to use independently. It was submitted, perhaps as a test of the opera's merits, to a contest sponsored by the National Federation of Music Clubs in March 1911. The second prize of $150 in the "song or aria" category awarded by judges Rossiter G. Cole, Reginald DeKoven, and Victor Herbert was applied to the expense of having the orchestral score copied.38

The remainder of the action of this long scene (154 pages), including the marriage ceremony performed by Obeska, is conveyed in a generally lyrical recitative style, with one more short air sung by Aedeta ("How Oft Beside Thy Lodge")39 and an excessively long and overly sentimental farewell scene, concluding with a trio by Daoma, Nemaha, and Aedeta ("Think Not of Me"/"What Should a Warrior Know of Fear").40 The scene concludes as the warriors charge offstage amid shouts and battle cries to the accompaniment of the "battle music" whose whole-tone structure (but not its melodic motive) was introduced briefly in the Act I prélude. Scene 2 follows without pause.

The long-planned revisions of Daoma were begun in late summer 1928, but the principal revisions were delayed until Cadman made his second pilgrimage to the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, N.H. in late summer 1937. He had gone to Peterborough with the intention of completing the revisions, but when he left in early October they were far from complete. Some of these involved the libretto, but the most significant revisions were in the music. During the past several years Cadman had begun to react to criticism that while his music contained good melodic material, he failed to develop it sufficiently. He became so absorbed in his attempts to invest Daoma with greater thematic development and improvements in instrumentation that the work was not finished until January 1939. In order to save time and effort, he tore apart the original bound manuscript of Daoma, inserting revised pages and sewing the new volume together as he proceeded, and again retitling it, this time Ramala.41 He avoided showing any of the opera to his colleagues at Peterborough (these included Harold Morris [1890-1964], Juilliard pianist; Gardner Read [b. 1913], a recent graduate of the Eastman School of Music; Charles Haubiel [b. 1892], founder of The Composers Press and teacher at New York University; and Marion Bauer [1889-1955], composer and writer), but he was persuaded to play his Omaha flute and demonstrate his process of "idealization." He was relieved that "such big people" should find it "of much interest," but it is obvious that he remained intimidated by "these guys here who are steeped in TRAINING (even the kids are)," whose academic preparation and technical facility he admired and envied, even when their aesthetics were repugnant to him.42

The revisions were minor, Cadman's intentions notwithstanding, having to do primarily with improving the dramatic aspect through the deletion of extraneous dialogue or music, the change of title, and the reorganization of the opera into four acts. The musical revisions were for the most part made to adjust to changes in text and to smoothen some of the more angular passages in the recitative (e.g. replacing octave leaps with conjunct progressions). He also removed certain flamboyancies from the orchestral accompaniment (e.g. sweeping scale passages) and deleted frequent orchestral interludes. The most significant changes occurred in Act II, Scene 1 where he eliminated the ineffective farewell scene with trio and completely rewrote Aedeta's air ("How Oft Beside Thy Lodge").

Cadman made one more attempt to have the opera produced. In 1939 he sent the newly revised piano-vocal score to the Metropolitan Opera Company.43 Almost 25 years after its first rejection it was again refused, and the composer belatedly began to come to the realization that he was a victim of an inexorable stylistic evolution. Shortly after the final rejection of Daoma he confessed his fears to Eberhart:

But within the past FIVE YEARS there has been a studied EFFORT on the part of composers as well as stage writers to leave BEHIND this old classic opera form and find a new one. . . . I am just broadminded enough . . . and contemporary in thought to FEEL that once in so often ANY form of art MUST change, . . . must give WAY to a new form, a new style and backed by new thought. Has it NOT been so in religion, . . . literature, . . . painters? It is also true that the older generation . . . does not like so many of the innovations and experiments . . . of these latter days. BUT we can't STOP them from going on, can we?44

Daoma, with its unusual length, its system of leitmotivs, its relatively elaborate orchestration (including various Indian drums and rattles), and its predominantly recitative style, had represented a radical departure from Cadman's accustomed style of the sentimental ballad. However, it was not a successful venture, for even if his ballad-style airs could have found acceptance on the opera stage, his recitative style could only be perceived as awkward and ill-suited even to the somewhat archaic language and exotic story of Daoma. Despite the revisions in later years and his repeated attempts to bring it to a performance, it remains unperformed in its entirety. Only two numbers extracted from the opera and arranged to form an orchestral suite in 1945 ("Spring Dance of the Willow Wands" from Act I, Scene 2 and "Processional and Dance of Sacrifice" from Act III, Scene 1) were to see public performance: these were conducted by Leopold Stokowski in a performance in the Hollywood Bowl on August 24, 1946, and were broadcast the following day on "The Standard Hour."45

For almost three years following the completion of Daoma in 1912 Cadman virtually abandoned composition with Indian melodies, although he did continue to present his Indian Music Talk and to arrange his older Indian pieces for various media for publication. But even before Daoma had been completed, he had begun to plan a second opera. He had come to the conclusion that it would be difficult to sell any full-length, three-act opera to a producer, and there was frequent complaint in his correspondence of 1912 of the enormous difficulties involved in composing and copying such a work. The earliest mention of a new, shorter opera dates from May 1912, when Eberhart suggested basing a one-act opera on Nathaniel Hawthorne's short story "Rappacini's Daughter" (from Mosses from an Old Manse). Cadman approved. Eberhart began work on The Garden of Mystery (the original name, Beatrice, was changed to The Garden of Death, and later to The Garden of Mystery) in the summer of 1912. The first draft of the libretto was sent to Cadman in October, just after Russell's rejection of Daoma, but it was not finished until the fall of 1914. The piano-vocal score was composed during the first six months of 1915.46

The Garden of Mystery was given its first performance on March 20, 1925 in Carnegie Hall in New York. This was not a full-scale production, but.a concert version presented as one of a series of benefit concerts for the local Music School Settlements. The program also included compositions by Chadwick and MacDowell, as well as a number of Cadman songs. The cast of five included well-known soprano Yvonne de Treville, contralto Helene Cadmus, tenor Ernst Davis, and baritones George Walker and Hubert Linscott; the American National Orchestra was directed by Howard Barlow. Dancers were provided by the Norges School of Rhythm.47

The response to The Garden of Mystery was mildly critical. The music was judged a pleasing but insufficient vehicle for proper development of the dramatic element, and librettist Eberhart was faulted for lack of dramatic sense. The customarily pro-Cadman journals, Musical America, Musical Courier, and Pacific Coast Musician, were quick to place the blame on limited staging and weak libretto, lamenting that Cadman's score had "gone for naught through inexpert handling of dramatic requirements."48

The Garden of Mystery was in almost every way the opposite of Daoma; it made no use of Indian melodies or subjects; there were only five characters and no chorus, although there was a short ballet; it was in one act, requiring only one stage set, and the orchestra was small. It was also a remarkable departure from Cadman's usual style, becoming at times chromatic and dissonant and employing unusual modal melodic patterns in an attempt to convey the sinister aspects of the story.

Cadman's third opera, The Robin Woman: Shanewis (Sha-NE-wis), was his first to be produced.49 It was undertaken in response to the urging of Cadman's associates in Denver that he compose an opera based on the life of Tsianina Redfeather, the young Cherokee-Creek Indian soprano who had been Cadman's principal soloist in his Indian Music Talk since 1913. After his experience with Daoma, it is doubtful that Cadman would have considered another Indian libretto were it not for his relationship with Tsianina. Like The Garden of Mystery, this was to be a "practical" opera—one act, a small number of characters, and a minimum of staging problems. Unlike The Garden of Mystery and Daoma, there were prospects of performances, not only in Denver, but also in Los Angeles. The Denver performance was to feature Tsianina and a professional tenor in the lead roles, with Denver musicians in supporting roles; the Los Angeles performance was to be presented by the San Carlo Opera Company, under the sponsorship of impresario L.E. Behymer.50

The earliest mention of The Robin Woman (Cadman referred to it merely as "Tsianina's opera") I have found is in the February 12, 1917 letter to Eberhart, but it is evident from the contents of this letter that the opera had been under discussion for some time. In contrast to Daoma, The Robin Woman was conceived as a relatively minor work which Cadman regarded primarily as a fulfillment of an obligation to his Denver friends, and perhaps as a "door-opener" for a production of Daoma if it were successful,51 and it occupied the composer for only slightly more than four months. (Daoma took over three years.) He began it in April 1917; by May 3 the piano-vocal score was one-third complete; if his projected schedule was kept, the piano-vocal score was finished by June and the orchestration by mid-August.52

Several of Eberhart's proposals for The Robin Woman libretto were flatly rejected by the composer. He objected to her specification of traditional beaded Indian costume on the grounds that it would be excessively expensive and, more importantly, unauthentic. This was to be based on the story of Tsianina's life and it had to be set in its proper time—a time when Indians had discarded traditional costume for either modern "store clothing" or what he called "mongrel" dress, with sombrero, often with a feather, red silk handkerchief and plaited hair. In further contrast with Daoma, the archaic language was to be replaced by modern speech.

Another of her suggestions met with more emphatic disapproval. The libretto was based on Tsianina's life, which, although colorful, did not provide a suitably dramatic conclusion for an opera. Eberhart had disregarded Cadman's suggestion of a contrived tragic ending, and had incorporated in her first sketches an ending based on "resignation" or a "sacrifice" of a nature not described specifically in the correspondence.

Cadman found this ending "undramatic—an old chestnut . . . which is absolutely worn threadbare," and cited Henry Russell's objections to such themes. Even more importantly, such a conclusion severely handicapped the composer who wanted to write "a rip-roaring ending to the story." He wrote to Eberhart:

I had hoped that you would carry out the tragic ending, with the Indian girl either killing herself or being killed or else stabbing the false lover in a passion or frenzy at the revelation of his perfidy. That would give an opportunity for BIG MUSIC and dramatic music. I fear you are thinking too much of Tsianina's own characteristics and her life and story of her career rather than the manufacturer of a plot that will be grand operish!53

If he had objections to unauthentic costume, he had no qualms about an unauthentic story if it enhanced the musical or dramatic potential of the opera.

Tsianina said you felt the tragic ending or the killing or being killed business was not "Indian" or "civilised Indian" for this age and day and therefore you felt we could be TRUER in our conception by not doing it. That may be ethnologically true and may be consonant with Tsianina's own character but I have never at any time associated this plot of hers with her life story save ONLY the opening which is that drawing room scene and the fact of her having a "benefactress." Outside these two TRUE events I had pictured the whole plot in the nature of a tragedy or melodrama such as one thinks of and associates with the grand opera stage.54

Eberhart wrote the libretto in April and May 1917. Tsianina and Cadman collaborated with her, and the final version featured a tragic ending devised by Tsianina and Eberhart: the traditional poisoned arrow with which the unfaithful lover is slain. In the interest of practicability of performance by a small opera company, the cast of characters was kept small—five in all, but advice offered by Behymer and by the director of the San Carlo Opera Company was disregarded in that a chorus was used. Scenery and costumes were simple, there being required only two sets, and modern dress or "mongrel" costume was specified for all but Shanewis who appeared in beaded white caribou.

It is paradoxical that The Robin Woman, for which Cadman had such modest aspirations, should prove to be one of the greatest professional successes of his career, and that the opportunity for that success should arise from matters political as well as artistic. In the fall of 1917 Giulio Gatti-Casazza, General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera, bowed to the ultimatum of his board of directors and agreed to cancel performances of all operas by German composers for the coming season. In order to fill the vacuum created by the cancellation of German works, Gatti-Casazza was forced to draw upon Italian, French, and Russian repertories, and to a limited extent, American. Earlier, during the initial stages of its composition, Cadman had requested a hearing for The Robin Woman at the Metropolitan Opera. Otto H. Kahn, chairman of the board of directors, agreed to such an audition when Cadman came to New York on his autumn tour, requesting only a copy of the libretto. It is evident from the tone of the letter that no serious intentions were involved.55

However by late summer, the Metropolitan Opera directors had become more serious in their search for new repertory, and a request came from Gatti-Casazza for the piano scores of all three of Cadman's operas. On September 4 the director requested samples of Cadman's orchestral technique. Kramer secured the orchestral score of Daoma from White-Smith's New York office. Two days later, before he could submit the orchestral score of The Robin Woman, Cadman received a telegram from Gatti-Casazza accepting The Robin Woman and stating the terms of the offer: for exclusive rights to the opera for the 1917-1918 season, a full orchestral score, and a right of renewal Cadman was to receive $50 per performance (a minimum of five performances) and retain publication rights for the piano-vocal score. Gatti-Casazza objected to the title, The Robin Woman, which Cadman and Eberhart had chosen, and suggested that it be called The Indian. The matter was resolved to the satisfaction of all when the title Shanewis: The Robin Woman was chosen.56 On September 15 Musical America announced the forthcoming production and on October 20 devoted a full page to discussion of the opera and its genesis. The Robin Woman captured the fancy of the American press as no previous American opera had done, for this was an opera set not in the legendary past of the American Indian nor in a foreign country, but in the present day and with contemporary characters and settings. Admittedly it dealt with a very limited segment of the American scene—the American Indian "in transition" in juxtaposition with wealthy Los Angeles society—but its characters were believable and the elements of the opera were familiar. Here at last was an opera that was not embarrassed to include modern dress, electric lights, ice cream and lemonade vendors, automobiles, "red, white, and blue" patriotism, high school girls, and even a stage band playing "jazz." And of course it was in modern English.

Cadman experienced some difficulty in convincing the director about the validity of some of these elements. He wrote to La Flesche of his involvement in the preparation and rehearsal of The Robin Woman:

Well, I am home for a few weeks before returning to the difficulty of seeing through the rehearsals for the opera. It took lots of work and not a little anxiety to get matters straightened out and make those foreigners understand that I fully expected to have my opera put on AS I WANTED IT and as nearly American in appearance as the story and stage action called for. I had a time but finally got my way. They are really sincerely cooperating with me and will follow out every suggestion now and they feel it MUST be a success. So I am glad to say that so far now, things are working out well.57

He could not have been more pleased by the selection of the singers for the five principal roles; all were American-born and -trained (one Canadian). Mezzo-soprano Alice Gentle ("a western girl who . . . looks the part of a modern Indian girl") was to sing the role of Shanewis; tenor Paul Althouse the role of Lionel Rhodes; baritone Thomas Chalmers ("the best American Baritone") the role of Philip Harjo; Kathleen Howard the role of Mrs. Everton; and Marie Sundelius the role of Amy Everton. The conductor was Roberto Moranzoni, the only foreign-born person having a major role in the production.

Tsianina and Eberhart were also present during rehearsals, the former brought specifically to act as adviser on Indian aspects of the production. A few days before the performance Alice Gentle was taken ill, and another American singer, contralto Sophie Braslau, was called upon to learn the role. Her first rehearsal was on Thursday morning, and by Saturday afternoon she had mastered the role sufficiently that it would be cited as "her best remembered achievement."58 Her principal difficulty seems to have been learning how to paddle a canoe in authentic Indian fashion; in this Miss Braslau, seated on a table in the lobby of the opera house, received instruction from Tsianina in the last hours before the performance on Saturday afternoon, March 23, 1918.59

The Robin Woman shared the program with two other short works based on contrasting elements of American life. Franco Leoni's L'Oracolo (first performance in London in 1905), set in San Francisco's Chinatown, had been performed earlier in the season. Henry F. Gilbert's The Dance in Place Congo was set near New Orleans and made use of popular American Negro tunes. Gilbert's work was not an opera, but a ballet adaptation of his symphonic poem of the same title composed in 1906. This was its first performance as a ballet.60

Because Leoni's L'Oracolo was a repetition, and Gilbert's The Dance in Place Congo was a short (although well-received) ballet, it was Cadman's opera which monopolized the attention of music critics and journalists. Predictably, the more popular music periodicals devoted extensive space to it. Musical America devoted almost four pages to photographs and a review by Herbert F. Peyser which thoughtfully considers the problems facing any composer of an opera in a contemporary setting. His harshest criticism was of the libretto with its awkward attempts at realism and the "stilted verbiage" that results from attempts to transfer ordinary party conversation to the operatic stage. He found a more serious defect in the introduction of elements of racial conflict in a manner that "fails of any conclusion because of its tenuousness and an amateurish and infantile handling that allows such possibilities as there are to slip by virtually unused," resulting in a libretto that was "slight in matter and void of dramatic conflict or interest."61

Peyser found the music much more satisfactory than the libretto and, although he had some reservations about Cadman's operatic technique, he pronounced The Robin Woman "in some ways the best native opera heard here. . . . It certainly should be the most serviceable." He regretted the composer's inclination to minimize Indian elements in The Robin Woman, and suggested that the opera would have benefited greatly from expansion of the "pow-wow" in Part II with ceremonial dances, and more extensive use of Indian melodies. Peyser also lauded Cadman's sense of the theater and at one point credited him with greater ability in that area than "any American represented here in the past ten or twelve years, with the sole exception of Victor Herbert." Although this opera might fail to survive at the Metropolitan because of an inadequate libretto, he predicted a successful future for Cadman in the opera house.

Peyser's review represented the middle ground among reactions to The Robin Woman. The unsigned review in the Musical Courier was, as always, unreserved in its praise for Cadman's work, proclaiming the opera to be "the best American work which the Metropolitan has yet produced," and "a triumph for American operatic music." There was no fault to be found in the work.62 New York newspaper reviews ranged from unstinting praise by William B. Chase (New York Times) to Sigmund Spaeth's (Evening Mail) pronouncement of "sincere mediocrity." Spaeth saw Cadman as "a novice in dramatic expression," and the opera as "little more than a succession of songs of his own familiar type, strung together with bald recitative." Henry T. Finck (Evening Post) was more moderate; Cadman had not composed the great American opera so eagerly awaited by all, but he did demonstrate the possibility of such a feat.63

The stage set for Part II had been designed by Norman and Edith Bel Geddes. The painted backdrop with top and side elements represented the vast expanse of the Oklahoma prairie with Indian tepees receding into the background beyond a river. It was intended to be a significant departure from the conventional Metropolitan Opera "scenery" in that it sought not natural realism, but psychological interpretation of the attitudes and environment of the Indian. The critics were almost unanimous in their praise of Geddes' work, but they found James Fox's Part I set (a California bungalow overlooking the Pacific Ocean) entirely conventional.64

The Robin Woman was presented a total of five times that season (March 23, 28; April 5, 10, and 15). It was mounted the following year for two performances (March 12 and April 4, 1919) with the same cast and conductor; on the same bill were Joseph Breil's The Legend and J. Adam Hugo's The Temple Dancer.65 It was also presented in Chicago in 1922 by the newly-formed American Grand Opera Company under the direction of Otto Luening—a production that was hailed as the first of an American opera by a company that consisted entirely of Americans.66

The first west-coast performance of The Robin Woman (under its subtitle, Shanewis) took place on June 24 and 28, 1926 in the newly-remodeled Hollywood Bowl with Tsianina singing the title role and direction by Gaetano Merola. The performances were accorded elaborate advance publicity, and impresario L.E. Behymer spared no effort to ensure a resounding success. This was the first opera to be produced in the Hollywood Bowl, and the production was, if anything, even more extravagant than Behymer's publicity had promised. Indian tepees and campfires extended several hundred feet up the slope behind the shell. Approximately 100 Hopi Indians descended in procession in festive garb and on horseback, while on the hills behind the shell other Indians carrying flares shouted war cries and chanted songs. All were visible to the audience, for the back of the shell had been removed for this performance. Cadman revised Part II for the Hollywood Bowl performance, expanding the role of Philip Harjo which was sung this time by American Indian baritone Chief Os-ke-non-ton.67 This revised version was published by The White-Smith Music Publishing Company in 1927.

The libretto of The Robin Woman is based loosely on certain aspects of Tsianina's career: a talented Oklahoma Indian girl, Shanewis (a phonetic approximation of Tsianina, this name first appeared in a song text in 1904, "The Tryst"68), had been discovered by "Mrs. J. Asher Everton, a prominent Los Angeles club woman" (Alice Robertson, Oklahoma congresswoman in real life) who sent her to New York (actually Denver) for voice training.

As the opera begins, the story departs almost totally from reality. Part is devoted to a reception and musicale given in southern California by Mrs. Everton (contralto) in honor of Shanewis (mezzo-soprano) who has just completed several years of vocal training. The basic conflict of the story emerges as Lionel Rhodes (tenor), the fiancé of Amy Everton (soprano), becomes infatuated with the singing and the beauty of Shanewis. Part II begins with a bustling Indian pow-wow set in Oklahoma. When the crowds depart, Shanewis, discovering Lionel's betrothal to Amy, denounces his faithlessness and delivers a bitter indictment of the white race in general for its exploitation of the Indian.

Be silent! Let me speak. For half a thousand years Your race has cheated mine With sweet words and noble sentiments, Offering friendship, knowledge,

protection.

With one hand you gave—niggardly, With the other you took—greedily! The lovely hunting grounds of my fathers You have made your own; The bison and the elk have disappeared

before you.

The giants of the forest are no more. Your ships infest our rivers, Your cities mar our hills. What gave you in return? A little learning, a little restless

ambition,

A little fire water, and many, many cruel

lessons in treachery!69

She announces her intention to return to the forest to heal her wounds, but Lionel pleads with her to remain with him. Shanewis' foster brother, Philip Harjo (baritone), suddenly rushes on stage and kills Lionel with bow and poisoned arrow. The opera comes abruptly to its conclusion as Shanewis, looking skyward, proclaims, "Tis well. In death thou art mine."

Although the musical style is essentially the same in both operas, The Robin Woman is a far less imposing work than Daoma, lacking the system of leitmotivs, the elaborate orchestration, and the full length in The Robin Woman, for by this time Cadman was becoming sensitive about the label of "Indian composer" that had become synonymous with his name, and the foreword of the 1918 edition contains a disclaimer of that label:

The composer does not call this an Indian opera. In the first place the story and libretto bear upon a phase of present-day American life with the Indian in transition. As it is not a mythological tale nor yet an aboriginal story, and since more than three-fourths of the actual compositions of the work lies within the boundaries of original creative effort (that is: not built upon native tunes in any way) there is no reason why this work should be labeled an Indian opera. Let it be an opera upon an American subject or if you will—an American opera.70

Most of the music appears to be originally composed, although Cadman noted in the foreword that a number of Indian melodies were used in various places in the opera, including both of Shanewis' brief narratives in Part I which were suggested by unspecified melodies in Frederick R. Burton's American Primitive Music.71 The first of these narratives (pages 23-26) relates how she first heard the song of the Robin Woman; the second (pages 37-39) how she was brought out of the forest by her benefactress.

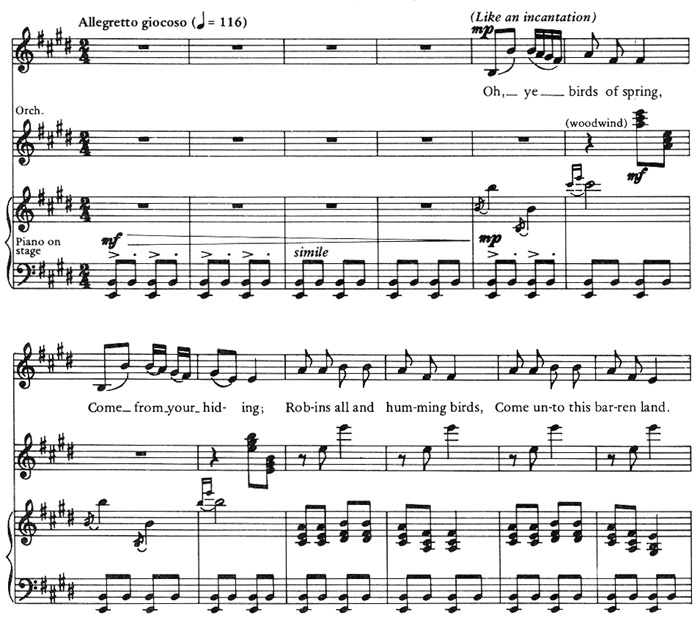

The air is employed in The Robin Woman, as in Daoma, as a vehicle for subjective expression during static moments in the dramatic action. Typical is the "Spring Song of the Robin Woman" ("Oh, Ye Birds of Spring"), the first of the two principal solos of Shanewis in Part I. This air is based on a Cheyenne melody recorded by ethnologist Natalie Curtis;72 it is provided with an Indian "drum-beat" accompaniment played on a piano on stage (Ex. 6).

Ex. 6. The Robin Woman, Part I, "Spring Song of the Robin Woman," p. 27.

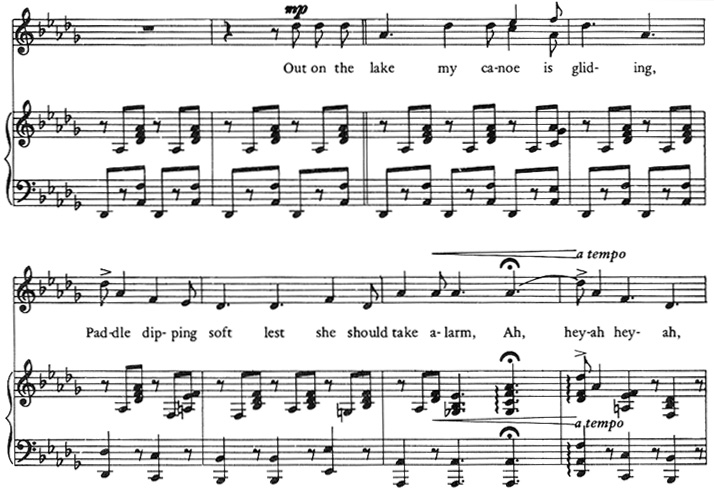

Her second air, the "Canoe Song" ("Out on the Lake my Canoe is Gliding") is a free "idealization" of an Ojibway song recorded and arranged by Burton,73 but the smoothly flowing melody and undulating  -

- meter are more suggestive of a gondolier's song than an Indian melody (Ex. 7).

meter are more suggestive of a gondolier's song than an Indian melody (Ex. 7).

Ex. 7. The Robin Woman, Part I, "Canoe Song," p. 34.

In contrast to Part I which was set in a luxurious Los Angeles mansion, Part II depicts a tribal "pow-wow" on the plains of Oklahoma and includes a remarkable mélange of such elements as Indian ceremonial dancers, half-breeds, white spectators, vendors of balloons, lemonade, and ice-cream cones (all represented by the chorus in a very simple musical style), and a "jazz-band of eight young people." Undoubtedly this was the first appearance of a "jazz-band" on the opera stage, but it should be noted that its very brief part (ten measures) carries only the merest suggestion of authentic jazz.

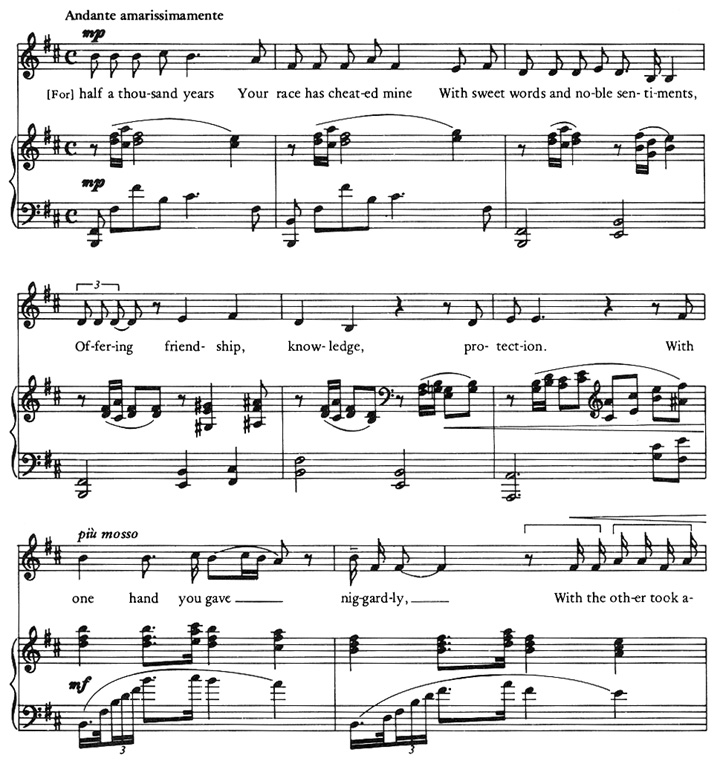

The musical high-point in The Robin Woman occurs in Part II when Shanewis delivers her indictment of the white man in an impassioned but all too brief recitative (Ex. 8).

Ex. 8. The Robin Woman, Part II, "For half a thousand years," p. 116.

The chant-like, hexatonic melody is an effective vehicle for this, the most serious and dignified passage in the entire libretto, and it stands in strong contrast to the generally perfunctory recitative that characterizes the rest of the opera. Had Cadman been able to sustain this quality throughout, The Robin Woman undoubtedly would have been far more successful than it was. As soon as Shanewis has delivered her indictment, the opera moves swiftly to its conclusion in a disconcertingly brief final scene in which Lionel, the deceitful white suitor of Shanewis, is slain by Philip Harjo. The Robin Woman, like its predecessor, Daoma, reaches an abrupt conclusion in which the faithful lovers are triumphant and the treacherous villain is destroyed. All of this is conveyed in a recitative ensemble that concludes all too precipitously with the excited chanting of a band of Indians.

Despite its weakness in both music and libretto, and despite its having been selected for performance by the Metropolitan Opera Company for reasons besides its actual artistic merit, The Robin Woman was a landmark in the history of American opera. The Metropolitan Opera Company had staged only five operas by American composers previously (Frederick H. Converse, The Pipe of Desire, 1910; Horatio Parker, Mona, 1912; Walter Damrosch, Cyrano de Bergerac, 1913; Victor Herbert, Madeleine, 1914; and Reginald DeKoven, The Canterbury Tales, 1917), but all of these were set in Europe with European characters except The Pipe of Desire, and this was based on American Indian legend of the distant past. The Robin Woman, therefore, was the Metropolitan Opera Company's first production with a contemporary American setting, the first with a libretto by a woman, and the first to see performance in a second season.

Although it has seen sporadic performances in recent years, The Robin Woman failed to survive in the repertory for reasons both dramatic and musical.74 Cadman was not comfortable then, nor was he ever to be, with larger forms, and in The Robin Woman, as in Daoma, he attempted to create a large form through a concentration of smaller forms. More serious was the inability of both librettist and composer to understand the necessity of character and plot development. In The Robin Woman, as in Daoma, Eberhart's overly simplistic plots and narrowly focused dialogue all too often provided little insight into the motivations and true nature of the character. She also failed to grasp the necessity of expansion of dramatic moments, and in both operas the climaxes are approached and left so precipitously as to leave insufficient time for the development of credibility of the action. Nor was Cadman's operatic skill a match for the challenge posed by his librettist. His ingenuous ballad style, adequate as it was for his numerous ballads, was too static and too shallow to succeed on the operatic stage, and he failed in his Indian operas as well as in the non-Indian to develop a convincing vehicle for the delivery of dialogue. As a whole Cadman's operas, both Indian and non-Indian, must be regarded less as significant contributions to the development of American opera than as monuments to the lofty but frustrated aspirations of a gifted composer of popular ballads.

1Another work, The Sunset Trail: An Operatic Cantata Depicting the Struggles of the American Indian against an Edict of the Federal Government (Boston: White-Smith Music Publishing Co., 1925) is frequently listed as an opera. It is, however, a cantata with optional staging directions based on an earlier choral work, The Sunset Trail, Opus 69 (Boston: White-Smith Music Publishing Co., 1920). For a provisional index of Cadman's works see Harry D. Perison, Charles Wakefield Cadman (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester, 1978), pp. 452-74.

2Marguerite Norris Davis, "Cadman," The Etude, June 1927, p. 427.

3Jeanne O. Potter, "Cadman of Pittsburgh," Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 4, 1915.

4Charles Wakefield Cadman: "An American Composer," The Musician, November 1915, p. 687.

5Letter, Cadman to Verna Arvey [September 1942], Cadman Collection of the School of Music of The Pennsylvania State University. All subsequent references to this collection will be indicated by PSU.

6"Cadman," The Musician, November 1915, p. 687.

7Boston: White-Smith Music Publishing Company, 1909.

8Fletcher was a holder of the Thaw Fellowship at the Peabody Museum of Harvard University. For a brief biographical sketch and bibliography of her writings see Walter Hough, "Alice Cunningham Fletcher," The American Anthropologist XXV (April-June 1923), pp. 254-58.

La Flesche was the son of Estamaza who was the son of a French trader and an Omaha Indian woman. Appointed to the Office of Indian Affairs in 1881 and the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1910, he was the author of numerous books and articles on Indian culture. For biographical details and bibliography see the memorial article, Hartley B. Alexander, "Francis La Flesche," The American Anthropologist XXXV (1933), 328-31.

9Letter, Cadman to La Flesche [December 4, 1908], in the Francis La Flesche Collection of the Nebraska State Historical Society, Lincoln, Nebraska. All subsequent references to this collection will be indicated by LFC.

10"Offer $10,000 for American Opera," Musical America, December 10, 1908, p. 5.

11Much of the discussion of the genesis of the libretto is found in their three-way correspondence preserved in LFC.

12Six of these recordings on wax cylinders are in PSU; most are in severely deteriorated condition.

13Letter, La Flesche to Eberhart, August 8, 1909, LFC.

14The starting and completion dates are noted in the autograph sketch (piano-vocal score) in the Library and Museum of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center (New York Public Library), hereinafter indicated by NYPL.

15The composition of Daoma is detailed in Cadman's numerous letters to La Flesche and Eberhart between June 1, 1909 and September 4, 1912, LFC.

16A copy of the printed program, "Testimonial Concert to Charles Wakefield Cadman," is in the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Cadman file. Nielsen performed Cadman's songs frequently.

17Letter, Cadman to Eberhart, March 9, 1912. This letter is in the large collection of letters and memorabilia owned by Constance Eberhart, daughter of Nelle Richmond Eberhart. All subsequent reference to this collection will be indicated by EC.

18This date appears at the end of the autograph full score (pencil) in PSU. This 877-page score lacks pages 355-84 of Act I; these are in NYPL.

19This ink manuscript is titled The Land of the Misty Water. Act I is in NYPL; Acts II and III are in PSU.

20Letters, Cadman to Eberhart, October 19, 1912, January 7, 1914, and May 7, 1914, EC. Cadman quotes Russell's letter in full.

21Agreement, Norman Geddes and Charles Wakefield Cadman, January 23, 1915, University of Texas at Austin, Humanities Research Center, Norman Bel Geddes Theatre Collection. For his description of Bel Geddes' work see letters, Cadman to La Flesche, January 24 [1915], LFC, and Cadman to Eberhart, January 26 [1915], EC. The water-color drawings are in NYPL. Bel Geddes' drama was never produced, but selections from Cadman's music were published in 1917 by White-Smith Music Publishing Company as a piano suite, and in 1920 by Boosey as an orchestral suite.

22Details of this competition are given in "The Musical Week in Los Angeles," The Musical Courier, July 4, 1915, pp. 21-27. An anonymous letter predicting the outcome of this contest was printed in The Musical Courier, July 22, 1914, p. 23. The writer accused the sponsors of this and the previous Metropolitan Opera contest of rigging the outcome and predicted that the prize would go to "one Charles Wakefield Cadman; or to one Geo. W. Chadwick; or a California composer. . . . If Cadman does not receive the prize a pupil of Chadwick's will." The contest was won by Horatio Parker's Fairyland; Parker was a pupil of Chadwick.

23A typescript draft of the libretto, together with many fragments of apparently earlier drafts, may be found in LFC.

24Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., [ca. 1900].

25In: Archaeological and Ethnological Papers of the Peabody Museum I, 5 (June 1893), 1-152.

26In: Twenty-second Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Part II (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1904).

27Letter, Cadman to La Flesche, May 4 [1911], LFC. This report, "The Osage Tribe: Rite of the Chiefs, Sayings of the Ancient Men," was published as the Thirty-Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology; 1914-15 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1921).

28Charles Wakefield Cadman, "The 'Idealization' of Indian Music," The Musical Quarterly I (July 1915), 387-96.

29This score (with the title Ramala taped over the title The Land of the Misty Water) is in NYPL.

30From the table of themes and motives in the piano-vocal score Land of the Misty Water. N.B.: This quotation differs in harmonization from the actual first statement of the theme in the opera. Used by permission of the Estate of Cadman.

31Daoma, autograph full score (pencil) in PSU, Act II, p. 1. All subsequent references are to this score unless otherwise noted.

32It is so identified in Act I, p. 83.

33Fletcher, "Study," p. 99.

34Idem, p. 87.

35Idem, p. 82.

36Idem, p. 90; Daoma, Act II, pp. 53-56.

37Letter, Eberhart to La Flesche, January 27, 1910, LFC. This air is the only part of the manuscript in ink.

38Letter, Cadman to La Flesche, March 12 [1911], LFC; "Big Convention," Musical America, April 8, 1911, p. 1.

39Act II, pp. 93-97.

40Act II, pp. 145-51.

41See footnote 29. Typescript copy of revised Libretto in PSU.

42Cadman's activities and thoughts while at Peterborough are detailed in three letters to Eberhart, one dated [September 9, 1937] and two [September 17, 1937], EC.

43This manuscript piano-vocal score is in NYPL. He apparently never prepared a revised full score.

44Letter, Cadman to Eberhart, [June 6, 1939], EC.

45Letter, Cadman to Ivor Darregg, August, 1946, PSU; R.D. Saunders, "Los Angeles," The Musical Courier, October 1, 1946, p. 30. N.B.: A home recording (disc) of the broadcast is in PSU.

46Letters, Cadman to Eberhart, [May 1912], and [October 24, 1912], EC. The piano-vocal score was published by J. Fischer in 1925.

47New York Times, March 21, 1925, p. 16.

48E.g., see "Injustice to Cadman," Pacific Coast Musician, April 11, 1925, p. 6.

49The Robin Woman (Shanewis): An American Opera (in One Act), vocal score (Boston: White-Smith Music Publishing Co., 1918). A revised edition was published by White-Smith in 1927. The autograph (pencil) piano-vocal score and manuscript orchestral parts are in NYPL.

50Letter, Cadman to Eberhart, February 12 [1917], EC.

51Letter, Cadman to La Flesche, April 30 [1917], LFC.

52"Cadman Goes East," Pacific Coast Musician, September 1917, p. 36; Letter, Cadman to Constance Eberhart [May 3, 1917], EC.

53Letter, Cadman to Eberhart, March 1 [1917], EC.

54Ibid.

55Letter, Otto H. Kahn to Cadman, May 9, 1917, Scrapbook I, pp. 2-3, PSU. This scrapbook also contains telegrams, clippings from newspapers and periodicals, autographed photographs of the cast, and an original stage set drawing (by Bel Geddes), as well as similar material from later productions of The Robin Woman.

56The series of telegrams detailing these events is found in Scrapbook I, pp. 4-9, PSU.

57Letter, Cadman to La Flesche, December 29 [1917], LFC.

58Oscar Thompson, The American Singer (New York: The Dial Press, Inc., 1937), p. 309.

59This was related by Tsianina in a private interview in Burbank, California on July 11, 1974. Miss Eberhart, also present at the final rehearsals, provides a similar account (private interview in New York, June 6, 1976). Both agree that Miss Braslau never did learn to paddle properly.

60Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 6th rev. ed., Nicolas Slonimsky (New York: G. Schirmer, Inc., 1978), p. 598.

61Herbert F. Peyser, "Native Composers Achieve Success at Metropolitan," Musical America, March 30, 1918, p. 2.

62"Cadman's 'Shanewis' Fine Lyrical American Opera," The Musical Courier, March 28, 1918, pp. 1-2.

63Clippings, Scrapbook I, pp. 14-20, PSU.

64Unidentified clippings, Bel Geddes Collection, NBG File, No. 40, 1-3.

65William H. Seltsam, Metropolitan Opera, Annals: A Chronicle of Artists and Performers (New York: The H.W. Wilson Company, 1947), p. 332.

66Unidentified newspaper clipping, Theodore Stearns, "Will Native Opera Reach Its Salvador," Scrapbook I, p. 64, PSU. Stearns was the music critic for the Chicago Herald-Examiner.

67"Fifth Summer Season at Hollywood Bowl," The Musical Courier, July 1, 1926, pp. 5, 32.

68New York: Edward Schuberth & Co., 1904.

69The Robin Woman (Boston: White-Smith Music Publishing Co., Copyright 1918), pp. 116-18. Copyright 1918 & 1927 by Edwin H. Morris & Company, Inc. Copyrights Renewed.

70Idem, p. 3.

71New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1902. In an interview, "Some Confessions about Shanewis," (Violinist, July 1918, p. 354), Cadman states that "perhaps twenty genuine Red Indian themes" were used, but he does not identify them.

72Natalie Curtis, The Indians Book (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1907), p. 180.

73Frederick R. Burton, American Primitive Music (New York: Moffat, Yard and Company, 1902), Part I: pp. 96-100, Part II: pp. 37-40.

74For a review of a workshop performance by the Central City Opera House Association (Central City, Colorado) in August, 1979 see Andrew Porter, "Singtime in the Rockies," The New Yorker, August 27, 1979, pp. 81-85.