Introduction

History has not always been kind to Alma Mahler. Upon reading her obituary in December, 1964, the politically-incorrect songwriter Tom Lehrer penned these words about her relationship with Gustav Mahler:

Their marriage, however, was murder.

He'd scream to the heavens above,

"I'm writing Das Lied von der Erde

And she only wants to make love!"1

In light of such lyrics, redeeming Alma might seem a formidable task. Companion, lover, and muse to Vienna's best and brightest in the early twentieth century, Alma inspired symphonies, paintings, and poems. Thanks to scholarship that began before her death, we know that she, too, had a creative spirit. Nevertheless, when I presented portions of this essay at the 2002 Annual Meeting of The College Music Society, I discovered that a number of my colleagues were unaware of her work. Thus, another look at Alma is warranted.

A composition student of Zemlinsky, Alma Schindler's music defined her early life. Upon her marriage to Mahler, however, she stopped composing at his insistence. Few of her works survive; fourteen songs have been published and recorded. "Die stille Stadt" is representative of her work and is examined in this essay.

A portrait of Alma emerges from the interconnectedness of influences on her and their manifestations in her music. For example, Alma adored Richard Wagner, calling him the "greatest genius of all time"—the song featured in this study begins with the Tristan chord.2 Her songs, perhaps even more than her writings (in which selective recall occasionally played a part), reveal Alma's true nature. They verge on the melodramatic, as did Alma; they are complex, as was Alma; they are contradictory, as was Alma. It is in her songs that we meet her, and it is through her songs that she assumes her rightful place.

The Woman

I first became intrigued with Alma Mahler while preparing a recital of songs by women composers. In order to understand her music, I needed to know more about the woman. Why is Alma's published output limited to fourteen songs? After all, unlike many other aspiring women composers of her time, she had access to musical training. This study of Alma begins with an overview of her life. For a more extensive inquiry, I refer the reader to Keegan's work, cited earlier. Keegan's monograph is a study of Alma's life and work and draws on original sources, such as Alma's handwritten diary, housed at the Van Pelt Library at the University of Pennsylvania. Keegan provides her own translations and sheds light on the contradictions between the diary, recorded contemporaneously, and Alma's memoirs, in which she portrays herself in the most flattering light possible. As Keegan points out, this was, of course, Alma's perfect right.3

To understand Alma, it is necessary to invoke the atmosphere of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Marked by the Weltschmerz that accompanied the decline of Romanticism, this was the era of Frank Wedekind's Lulu plays and Dr. Freud's theories of sexuality. Writer Stefan Zweig described Vienna as "sticky, perfumed, sultry, unhealthy."4 It was in this hothouse that Alma Schindler came of age.

The daughter of landscape painter Emil Schindler, Alma spent hours in her father's studio, where he often sang to her. Perhaps inspired by his voice, she began composing songs at age nine. Sometime between 1897 and 1900, the year Alma turned twenty-one, Alexander von Zemlinsky became her composition teacher. They shared an infatuation with Wagner, and Zemlinsky became one of her many suitors.

In 1901, mutual friends introduced her to Gustav Mahler. In a lengthy letter to her upon their engagement, Gustav made it clear that she was to live for his music, not hers. He called the idea of a husband and wife team of composers, such as Robert and Clara Schumann, "ridiculous" and "degrading" and insisted that Alma stop composing.5 Somewhat melodramatically, Alma agreed to give up everything for him, to "live only for him."6 She had dated a succession of older men, perhaps hoping to replace the father she had lost at age twelve. Gustav was nearly twenty years her senior, and she had a keen appreciation of his artistic status, so it is not surprising that she deferred to him. She became his copyist, but this vicarious form of composition did not satisfy her. The resentment spilled over into their daily lives and threatened the marriage.

Alma and Gustav were married in 1902, and later that year, daughter Maria was born. Daughter Anna followed in 1904. Maria's death from scarlet fever in 1907 drove Alma and Gustav apart, and the marriage reached a crisis in 1910 when Alma had an affair with architect Walter Gropius. Gustav began to understand that in preventing his wife from composing, he was inflicting a grievous wound on her and on their relationship. He retrieved her songs and played them. She must have been pleased to hear her music again after many years of silence. He insisted that she polish the songs and prepare them for publication. Fünf Lieder were published in 1910, and in March, 1911, Frances Alda premiered "Laue Sommernacht" in New York.

After Gustav's death in May, 1911, Alma began a relationship with Oskar Kokoschka, who painted her several times. In "Die Windsbraut" ("The Tempest," 1914), the two of them lie, partially clothed and intertwined, in a stormy Expressionistic sea of broad brush strokes and bold color.7 In a letter sent on her 70th birthday, Kokoschka called her a "wild thing," saying, "We'll always be on the stage of life, we two, when disgusting banality, the trivial visage of the contemporary world, will yield to a passion-born splendour. . . ."8

A second set of Alma's songs, Vier Lieder, was published in 1915, the same year as Alma's marriage to Walter Gropius. Their daughter, Manon, was born in 1916. Gropius served as an officer at the front during World War I, and his absences put a strain on the marriage. Alma and Gropius divorced in 1920. Manon died of polio in 1935; Alban Berg's Violin Concerto is dedicated to her.

On a visit to Berlin in 1915, Alma had come across one of Franz Werfel's poems, Der Erkennende, which she set to music.9 This song was included in a third set, Fünf Gesänge, published in 1924. In 1917, she met Werfel and began an affair with him. They married in 1929, fled the Nazis during the 1930s, and settled in America in 1940. They were together for nearly 30 years, until Werfel's death in 1945.

In 1947, Alma traveled to Europe but found her former home destroyed and her manuscripts burned. Returning to America, she continued her high-profile life in New York, publishing And the Bridge is Love in 1959 and Mein Leben in 1960. Alma died in New York in 1964 at the age of 85.

In the course of her long life, Alma befriended almost everybody who was anybody in the artistic life of the first half of the twentieth century. In addition to her famous husbands and lovers, a few of the illustrious names that filled her address book were Theodor Adorno, Enrico Caruso, Thomas Mann, Darius Milhaud, Giacomo Puccini, Bruno Walter, and Thornton Wilder.

The Songs

A colleague of mine, researching Zemlinsky's songs, interviewed Zemlinsky's widow prior to her death. Mrs. Zemlinsky reportedly said that Alexander never got over Alma.10 What manner of woman inspired such feelings? The answer lies in her songs. For the reader unfamiliar with her work, and to contextualize the song featured in this essay, Table 1 lists the published songs.

Table 1. The Published Songs of Alma Mahler

| Fünf Lieder, composed circa 1900-01, published 1910 |

| Die stille Stadt (Richard Dehmel, 1863-1920) In meines Vaters Garten (Otto Erich Hartleben, 1864-1905) Laue Sommernacht (Gustav Falke, 1853-1916) Bei dir ist es traut (Rainer Maria Rilke, 1875-1926) Ich wandle unter Blumen (Heinrich Heine, 1797-1856) |

| Vier Lieder, "Licht in der Nacht" and "Erntelied" dated 1901, "Waldseligkeit" and "Ansturm" dated 1911, published 1915 |

| Licht in der Nacht (Otto Julius Bierbaum, 1865-1910) Waldseligkeit (Dehmel) Ansturm (Dehmel) Erntelied (Falke) |

| Fünf Gesänge, generally attributed to circa 1900-01, except "Der Erkennende" written in 1915, published 1924 |

| Hymne (Novalis, 1772-1801) Ekstase (Bierbaum) Der Erkennende (Franz Werfel, 1890-1945) Lobgesang (Dehmel) Hymne an die Nacht (Novalis) |

Alma's songs are chromatic, dramatic, and erotic, but every musical gesture is in service of the text. An exquisite sensitivity to the poetry is on display at all times. Alma was drawn to mysticism and the contemplation of the inner life.11 For her texts, she frequently chose her contemporaries, including the Symbolist poets. Prevailing themes are night versus light, loneliness and love, and sexual union as spiritual communion. Alma's provocative music is an apt vehicle for the vivid imagery of this poetry.

The vocal lines are declamatory and conform to speech rhythms. The vocal writing balances scalar motion with large, emphatic leaps. The leaps are vocally awkward—tritones and sevenths are not uncommon—but they animate the text. The vocal line often centers on D or has D as a prominent pitch. The voice seldom arrives at a musical goal as the song comes to a close; it is up to the piano to complete the musical thought.

The drama in these songs is in the piano. Alma's comfort with this instrument is evident as she employs huge chords reminiscent of Brahms and Liszt. Her accompaniments are complex, and her rapid harmonic rhythm adds a restless quality. The textures are dense—at times, using the pedal, five octaves sound at once. Major and minor chords are rare; diminished and augmented sonorities prevail, often with atypical spellings. Linear motion dictates the use of enharmonic equivalents and allows Alma to move between distant keys. Her harmonies, like her texts, are bold and ambiguous.

Formally speaking, ideas are varied and developed as they are exchanged between voice and piano. The beginning of a song may be repeated at the end, thus rounding out the form, or an ending may occur on an unresolved harmony. Fermatas and caesuras delineate smaller sections. Frequent tempo fluctuations add expressiveness.

It is not known how much of Gustav appears in the published version of Alma's songs. As a conductor, he was "re-creative rather than interpretative," and he may not have been able to resist making some changes of his own.12 Nevertheless, he probably did not want to risk further damage to the marriage by imposing his will on her music. Absent her manuscripts, the evidence is problematical, but there are compelling differences in their compositional styles.13 For example, Gustav wrote only one love song, "Liebst du um Schönheit," composed for Alma in 1903.14 It contains none of the passionate outpourings of Alma's music; the setting of this same text by Clara Schumann is more amorous than Gustav's effort. Alma's writing is more chromatic than her husband's, and her piano parts are much heavier. In short, these are fundamentally Alma's songs.

"In meines Vaters Garten" from the first set, Fünf Lieder, may recall the time Alma spent in the company of her beloved father. At slightly over six minutes, it is the longest of any of Alma's songs. Enharmonic equivalents permit unexpected shifts between keys a tritone apart. The last two songs in this set, "Bei dir ist es traut" and "Ich wandle unter Blumen," are more conventional than the first three and may have been written before Zemlinsky exerted his influence on her writing. The dating of her songs is open to question, and scholars differ on the year when Zemlinsky became her teacher, making any comparison of her pre- and post-Zemlinsky compositions problematical.15

"Licht in der Nacht" opens the second set, Vier Lieder. Major and minor seconds between the voice and piano create dissonant clashes that reflect the darkness of the poetry. The piano parts in this set are fantasia-like, a fitting accompaniment to these fervent texts.

The setting of Werfel's poem, "Der Erkennende," appears in the last set, Fünf Gesänge. It is possible this is the last piece she wrote. If so, there is a certain poignancy to the final lines of text: "One thing is clear: Nothing is ever mine. My only possession is to know this."16

"Die stille Stadt"

A close reading of one of her songs deepens our understanding of Alma as it illustrates her technique. The intent here is to provide the means to an informed, effective performance of her music as well as an analytical and interpretive guide that can be used for studying her other songs. I chose "Die stille Stadt" for my recital, primarily because it best accommodates my lyric soprano voice. Many of Alma's songs require a dramatic instrument and a range more commonly associated with a mezzo-soprano, Alma's fach.17

Richard Dehmel wrote the poetry for "Die stille Stadt." Dehmel was a radical, and radicals have always had an appeal for young intellectuals like Alma.18 She used four of his texts, more than any other single poet. Other composers who set Dehmel include Pfitzner, Schoenberg, Strauss, and Webern.19 Dehmel's Verklärte Nacht inspired Schoenberg's string sextet of the same name. The text and translation of "Die stille Stadt" are in Table 2.20

Table 2. "Die stille Stadt" (The Quiet Town)

| Liegt eine Stadt im Tale, ein blasser Tag vergeht, es wird nicht lang mehr dauern, bis weder Mond noch Sterne, nur Nacht am Himmel steht. |

A town lies in the valley, a pale day passes; it will not be long now until nei- ther moon nor stars, only night stands in the sky. |

| Von allen Bergen drükken Nebel auf die Stadt, es dringt kein Dach noch Hof noch Haus, kein Laut aus ihrem Rauch heraus, kaum Türme nach und Brükken. |

From all the mountains fog presses on the town; it penetrates no roof, nor farm, nor house; no sound comes out of its smoke, barely towers and bridges. |

| Doch als dem Wandrer graute, da ging ein Lichtlein auf im Grund und aus dem Rauch und Nebel begann ein Lobgesang aus Kindermund. |

But as the wanderer felt dread, a little light went on in the valley, and out of the smoke and fog began a song of praise from the mouth of a child. |

The song breaks down into sections based on score indications, thematic material, and key area (Table 3).

Table 3. Formal sections of "Die stille Stadt"

| Measure number | Score indication | Thematic material | Key area |

| 1 | Andante | Introduction | D: |

| 2 | Träumerisch | A1 | d: |

| 6 | a tempo | A2 | D:/d: |

| 10 | Extension/Interlude | d: | |

| 14 | a tempo | A3 | d: |

| 18 | sehr drängend | B | D is prominent |

| 22 | Wieder zurückkehrend zu Tempo I |

C | F is prominent |

| 26 | Tempo I | Lichtlein | D:/d: |

| 34 | Tempo I/Sehr langsam |

Postlude/reprise of Introduction |

D: |

The divisions that characterize Alma's musical structures appear to disrupt the flow but not without purpose. When these devices appear in her songs, they are always in service of the mood and the poetry.

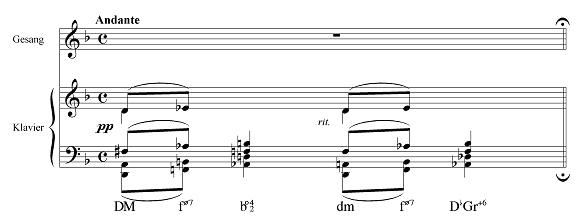

The musical materials of the song are established in the first measure. "Die stille Stadt" begins on a D major triad, but an F half-diminished seventh, the Tristan chord, appears on the second half of the first beat (Example 1).

Example 1. "Die stille Stadt," m. 1.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

It is spelled F,  , B,

, B,  . When it first appears in his opera, Wagner spells it F,

. When it first appears in his opera, Wagner spells it F,  , B,

, B,  ; in a later incarnation, it is spelled F,

; in a later incarnation, it is spelled F,  ,

,  ,

,  , and functions as a supertonic seventh chord in

, and functions as a supertonic seventh chord in  minor. Alma uses neither of Wagner's spellings, and both her approach and resolution are different, but there is no mistaking the sound of the Tristan chord. Given that Alma often played Wagner at the piano, it is not surprising that his ghost haunts her music.21

minor. Alma uses neither of Wagner's spellings, and both her approach and resolution are different, but there is no mistaking the sound of the Tristan chord. Given that Alma often played Wagner at the piano, it is not surprising that his ghost haunts her music.21

The varied repetition and mode mixture of this first measure are present throughout the song. As the opening half-bar gesture is repeated, a D minor triad replaces the original D major. The one-measure introduction ends on an inverted  German augmented sixth. This chord reappears in measure 25 at the high point of the song. A fermata at the end of the measure creates the first division. In addition to allowing the mood to settle over the listener, this moment gives the singer an opportunity to prepare for her entrance.

German augmented sixth. This chord reappears in measure 25 at the high point of the song. A fermata at the end of the measure creates the first division. In addition to allowing the mood to settle over the listener, this moment gives the singer an opportunity to prepare for her entrance.

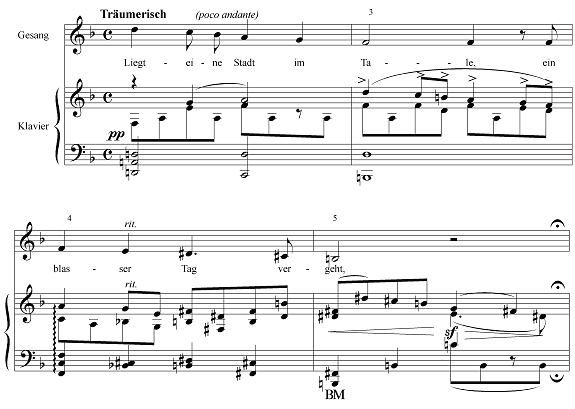

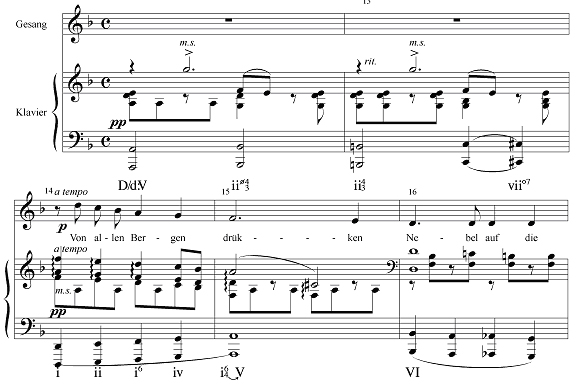

With a score indication of Träumerisch ("dreamlike"), the voice begins a descent through the D minor scale (Table 3 [A1] and Example 2).

Example 2. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 2-5.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

When the piano imitates this line in the next measure, B natural replaces  . The chromatic alterations are articulated with accents, and the B natural forecasts the goal of the opening phrase, a B major triad. The descending line mimics the setting sun as "a pale day passes." With the second fermata, at the end of measure 5, the music pauses to observe the scene. The next phrase begins like measure 2 but the piano varies the repetition yet again, this time by sharping the C (Table 3 [A2] and Example 3).

. The chromatic alterations are articulated with accents, and the B natural forecasts the goal of the opening phrase, a B major triad. The descending line mimics the setting sun as "a pale day passes." With the second fermata, at the end of measure 5, the music pauses to observe the scene. The next phrase begins like measure 2 but the piano varies the repetition yet again, this time by sharping the C (Table 3 [A2] and Example 3).

Example 3. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 6-7.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

In measure 10, an uneasy, syncopated figure, which will recur in measure 22, underscores "Nacht" (Example 4).

Example 4. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 10-11.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

As expected, the piano imitates the voice a measure later. The phrase is extended, forming an interlude before the second verse of the poem (Example 5).

Example 5. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 12-16.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

A linear ascent in the bass, moving in octaves from dominant to dominant in D, begins in this interlude and accompanies the third statement of the D scale (Table 3 [A3] and Example 5, measure 14). Following a deceptive cadence in measure 16, a complementary linear descent takes us to the beginning of the next stanza of this verse. The ascent accompanies "From all the mountains," and the descent describes the fog pressing down on the town.

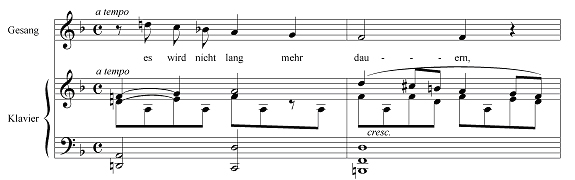

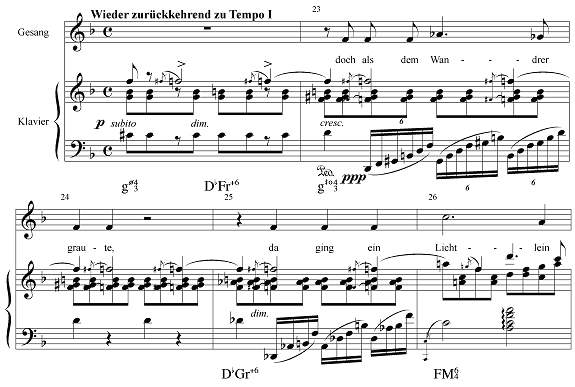

At this point, Alma introduces altogether new music (Table 3 [B] and Example 6), highlighted by contrary motion around D in the outer voices.

Example 6. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 18-20.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

This phrase is a delight to sing. Marked sehr drängend ("very urgently"), the feel of both the dotted rhythms and the German diphthongs in the mouth energizes the text. The section ends on a G half-diminished seventh (over E) spelled G,  ,

,  , F. Alma's use of the

, F. Alma's use of the  serves as another reminder of the song's pitch center, further reinforced when, a few measures later, the

serves as another reminder of the song's pitch center, further reinforced when, a few measures later, the  resolves to D.

resolves to D.

Leading into the third verse, the rhythmic pattern of measure 10 reappears, but Alma introduces more new pitch material (Table 3 [C] and Example 7)urgent sextuplets in the left hand and an insistent repeated F in the right, approached each time by a grace note on  .

.

Example 7. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 22-26.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

The mood has become sinister, and the tension is heightened by the chromatic mutations of the G half-diminished seventh. When  is raised to B natural, the chord becomes a

is raised to B natural, the chord becomes a  French sixth. The

French sixth. The  , enharmonically spelled as

, enharmonically spelled as  , resolves up to D. When the G is then raised, the chord becomes a dissonant

, resolves up to D. When the G is then raised, the chord becomes a dissonant  fully-diminished seventh as the text proclaims, "But just when the wanderer started to feel dread. . . ." The D is flatted, and an enharmonic change (

fully-diminished seventh as the text proclaims, "But just when the wanderer started to feel dread. . . ." The D is flatted, and an enharmonic change ( to

to  ) transforms the chord into a German sixth that resolves to an F major six-four chord on "Lichtlein." One of the few major triads in the song, and the only one in second inversion, it sounds especially bright here as the music opens up to admit the light.

) transforms the chord into a German sixth that resolves to an F major six-four chord on "Lichtlein." One of the few major triads in the song, and the only one in second inversion, it sounds especially bright here as the music opens up to admit the light.

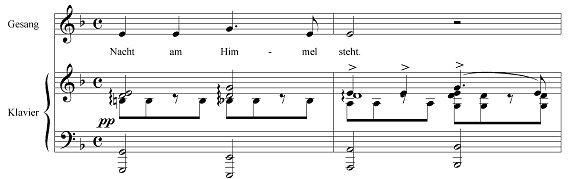

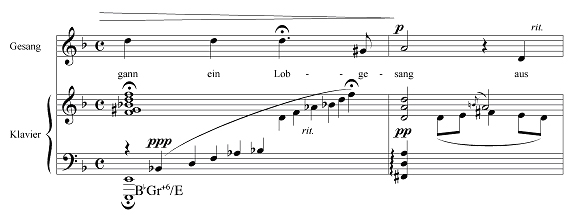

We have reached the high point, and the tension now eases, relaxing into a cadenza in the piano that outlines a  German sixth over an E pedal, with a fermata in the voice on "Lobgesang" (Example 8).

German sixth over an E pedal, with a fermata in the voice on "Lobgesang" (Example 8).

Example 8. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 30-31.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

The "song of praise" begins in this measure in the piano and recurs in the Postlude (Example 9).

Example 9. "Die stille Stadt," mm. 34-36.

Alma Mahler, from Sämtliche Lieder, 5 Lieder, "Die stille Stadt" © 1910 by Universal Edition A.G., Wien/UE 18016

Measure 1 is then reprised before the song concludes on a D major triad.

"Die stille Stadt," like Alma's other songs, demands an accomplished pianist, an artist capable of illuminating the counterpoint that throws the piano line into relief. The singer must be able to color her voice to portray both fear and serenity. The thickness of the piano texture presents a significant challenge for both pianist and singer, particularly in the soft passages. The pianist must take great care not to overwhelm the voice. Given the importance Alma attaches to her texts, precise diction is imperative if the singer is to be heard and understood.

Conclusion

After Gustav's death, Alma was unable to recover her creative energies to any significant degree. There are any number of reasons for this. She lived at a time when women typically did not pursue their own careers, and she was not fully developed as a composer before she was forced to give it up. For all of her audacity (at one of her first meetings with Zemlinsky, she reportedly said to him, "Do you think that someone as extraordinarily creative as I am could still not have heard your opera?"), she may have lacked the confidence to compose without the guidance and support of a teacher.22 It is certain that Alma had no role models; she was a unique creature. Had another woman composer been available as a mentor, Alma may not have welcomed the association. It must be remembered that Alma was weaned on Nietzsche and always believed herself the Überwoman.

If this seems arrogant, there is another, more disturbing example: Alma's sporadic anti-Semitism. She was married to two Jews, Mahler and Werfel, and fled Europe on the arm of the latter. They settled in Los Angeles and were surrounded by other Jewish émigrés. But Alma, never forgetting her German blood, could not refrain from making chauvinistic remarks. For their part, her friends forgave her, presumably because they found her so charming that they did not wish to be deprived of her company.

Nor she of theirs. In her various liaisons, sex was not the point; Alma was enthralled by creativity and artistic genius. She believed she was called not to be a passive Muse to these men but an active partner in fulfilling their destinies.23 If she was martyred to Mahler, there can be no doubt that she played a significant role in his success and, through her later writings, in his legacy. As for the men in her life, if they were initially drawn to her for her beauty—photographs of her show a hauntingly beautiful woman with large, expressive eyesthey stayed for her intelligence and high spirits.

These traits are revealed in her songs. Alma's music is evocative, occasionally excessive, and her compositional choices reflect her volatility—she vacillates between conventional harmonic progressions and startling chromaticisms, not quite settling into one or the other. Zemlinsky felt she lacked "musical order," a "tonal plan."24 Table 3 suggests that some sense of tonal organization is present in "Die stille Stadt": the song mixes D major and D minor, with a hint of F major to underscore "Lichtlein", the "little light" that penetrates the foggy atmosphere described by the text. But tonal coherence was not Alma's overriding consideration. Her enigmatic harmonies are compelled by her poetic choices. Time and time again, she demonstrates that her music serves the text. Joseph Labor, her first composition teacher, told her, "You would do better to have one theme and bring out more mood."25 But consider the emotional range of the poetry she set. If she did not follow Labor's advice, it was because the complexity of her chosen texts demanded thematic variety; if unity had to be sacrificed as a result, so be it. Viewed in this light, Labor's criticism is less valid.

Nevertheless, the songs are youthful compositions and as such betray a certain impulsiveness. One wonders what might have happened if she had been allowed to develop her compositional abilities to their fullest. Would maturity have resulted in a more disciplined idiom? Or would the irrepressible Alma have continued to write exuberant and extravagant music? One also wonders what else we have lost. Apart from two other songs in manuscript, these songs are all we have of her creative output; the rest of her scores were destroyed in the bombing of Vienna in World War II.26 She endured much—the loss of husbands, lovers, children, her home in Austria. But the greatest loss may be that of her music, a loss we share with this remarkable woman.

Sources

Banks, Paul, and Donald Mitchell. "Gustav Mahler," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 11, ed. Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan, 1980, 505-531.

Click, Sarah D. "Art Song by Turn of the Century Female Composers, Lili Boulanger and Alma Mahler." D.M.A. diss., University of North Texas, 1993.

Filler, Susan M. "A Composer's Wife as Composer: The Songs of Alma Mahler." The Journal of Musicological Research 4 (1983): 427-41.

________. Gustav and Alma Mahler: A Guide to Research. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989.

Franklin, Peter. "Alma Maria Mahler," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 15, 2d ed., ed. Stanley Sadie, exec. ed. John Tyrrell. New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc., 2001, 601-602.

________. "Gustav Mahler," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 15, 2d ed., ed. Stanley Sadie, exec. ed. John Tyrrell. New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc., 2001, 602-631.

Jarman, Douglas. Alban Berg: Lulu. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Keegan, Susanne. The Bride of the Wind: The Life of Alma Mahler. New York: Viking Penguin, 1992.

Kravitt, Edward F. "The Lieder of Alma Maria Schindler-Mahler." The Music Review 49, no. 3 (1988): 190-204.

Levitz, Tamara. "Richard Dehmel," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 7, 2d ed., ed. Stanley Sadie, exec. ed. John Tyrrell. New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc., 2001, 139-140.

Mahler, Alma. Songs of Alma Mahler. Virginia Dupuy, Simon Sargon. Peterborough, NH: Gasparo Records, Inc., 1997. CD GG-1015.

Murray, Monica Joanne. "A Parallel Study of Solo Vocal Works by Women Composers: Comparison to Works from the Standard Repertory." D.M.A. diss., University of Minnesota, 1993.

Newsome, Tim. "Tom Lehrer." http://wiw.org/~drz/tom.lehrer/the_year.html#alma; accessed May 1, 2002.

Pendle, Karin. ed. Women and Music: A History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Schindler-Mahler, Alma Maria. Sämtliche Lieder. Universal Edition no. 18016, 1999.

Smith, Warren Storey. "The Songs of Alma Mahler." Chord and Discord 2, no. 6 (1950): 74-78.

Vergo, Peter. Art in Vienna, 1898-1918. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1993.

1Tim Newsome, "Tom Lehrer," http://wiw.org/~drz/tom.lehrer/the_year.html#alma, accessed May 1, 2002.

2Susanne Keegan, The Bride of the Wind: The Life of Alma Mahler (New York: Viking Penguin, 1992), 56, quoting Alma Mahler, from her handwritten diary. The title of Keegan's book is taken from Oskar Kokoschka's painting of himself with Alma. It was also the title of the 2001 Paramount Classics film directed by Bruce Beresford.

3Ibid., 308.

4Douglas Jarman, Alban Berg: Lulu, Cambridge Opera Handbooks (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 92.

5Keegan, 97, quoting part of a letter reproduced in Henri Louis de la Grange, Mahler, vol. I (Gollancz, 1974), 684-690, and Karin Pendle, ed., Women and Music: A History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 135.

6Keegan, 98, quoting Alma Mahler, from her handwritten diary.

7The painter Gustav Klimt, an early suitor, also made portraits of her.

8Keegan, 304, quoting Alma Mahler, And the Bridge is Love (Hutchinson, 1959), 278.

9Ibid., 214.

10Private telephone conversation with Lesley Manring.

11Edward F. Kravitt, "The Lieder of Alma Maria Schindler-Mahler," The Music Review 49, no. 3 (1988), 192.

12Paul Banks and Donald Mitchell, "Gustav Mahler," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 11, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), 513.

13See Kravitt, 197-203, for an excellent discussion of this matter.

14Warren Storey Smith, "The Songs of Alma Mahler," Chord and Discord 2, no. 6 (1950), 77.

15Filler places Zemlinsky's appearance at 1897, Pendle at 1900. Susan M. Filler, Gustav and Alma Mahler: A Guide to Research (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989), xxvii, and Pendle, 134.

16Translation by the author.

17Pendle, 134.

18Kravitt, 192.

19Tamara Levitz, "Richard Dehmel," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 7, 2d ed., ed. Stanley Sadie, exec. ed. John Tyrrell (New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc., 2001), 140.

20Alma Maria Schindler-Mahler, Sämtliche Lieder, Universal Edition no. 18016, 1999. Translation by the author.

21The chord appears in at least one other song. See Smith, 77.

22Keegan, 55, quoting Alma Mahler, from her handwritten diary.

23Pendle, 135-6.

24Keegan, 60, quoting an undated letter, Zemlinsky to Alma Schindler, Van Pelt Library.

25Ibid., 58, quoting Alma Mahler, from her handwritten diary.

26Pendle, 136, and Kravitt, 200.