Introduction

The year 1889 marked the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and the nation celebrated with the Paris Exposition Universelle, an extraordinary World's Fair. The importance of the event was emphasized by the construction of the Eiffel Tower, built for the occasion.

Twenty-seven year old Claude Debussy frequented the many exhibits from all over the world and was enthralled by the gamelan music and the dancing it accompanied that he witnessed in the Javanese pavilion. The experience inspired him later to capture the sounds of the gamelan in his 1903 piano composition Pagodes. This article examines how he did so and also places Pagodes' composition within the contexts of contemporary documentation of the Exposition, his other works, and recent scholarship about exoticism. Four principal elements of gamelan music—timbre, tuning, polyphonic layering, and rhythmic structure—are examined through the eyes of twentieth century ethnomusicologists. The same four elements are analyzed in Pagodes. Elements of Western musical composition complement the analysis. What emerges is not a vague impression but, rather, a remarkably successful rendition of the Eastern gamelan on the Western piano.

1889 Paris Exposition Universelle

Edward Said, in his classic study entitled Orientalism, writes of the Orient's special place in European Western experience:

The Orient is . . . the place of Europe's greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other.1

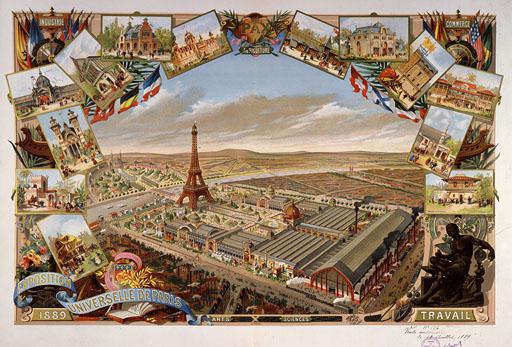

Against a backdrop of fascination with this “Other,” the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle took place over the course of six months between May 6 and November 6. Of five Expositions Universelles roughly a decade apart,2 a special significance graced this one, timed one hundred years after the French Revolution. Twenty-five million people3 visited the grounds along the Seine River in what is now Parc Champs de Mars, headed by the newly constructed Eiffel Tower and featuring displays in the form of concert halls, galleries, cafes, boutiques, villages, and pavilions. (See Figure 1 for the General View of the grounds.) France’s colonies Algeria, Tunisia, Senegal, Gabon-Congo, Oceania, Cambodia, Annam, Tonkin, and Cochin China (these last three comprising today's Vietnam) were all represented. Countless other countries brought their own exhibits at France's invitation. One of the most successful world's fairs in history, it had enormous political, technological, historical, cultural, and musical significance.4

Figure 1. General View of 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. (The Art Achive/Musee Carnavalet Paris/ Dagli Orti)

Figure 1. General View of 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle. (The Art Achive/Musee Carnavalet Paris/ Dagli Orti)

While representation of the exotic was already popular in musical and stage works with characters, stories, dancing, and music in imitation of the Other, the 1889 Exposition for the first time brought authentic exotic music to visitors to experience close-up.5 Julien Tiersot, a musician, scholar, and eyewitness to the Exposition, rhapsodized over its wonder and importance:

Rome is no longer in Rome; Cairo is no longer in Egypt, nor is the island of Java in the East Indies. All of this has come to the Champ de Mars. . . . Without leaving Paris, it will be feasible for six months to study at our leisure, at least in their exterior manifestations, the habits and customs of faraway peoples. . . . music being among all of these manifestations the one most striking . . . The thing most interesting of all and most novel for us, in the Javanese village, [is] a spectacle of sacred dances, accompanied by a music infinitely curious, which will take us as far as possible from our civilization.6

Tiersot's book includes studies of music from many exotic countries represented at the Exposition ranging from Africa to Norway, Vietnam to Roumania, America to Egypt. His chapter on Java describes gamelan instruments and elements of musical composition, and contains transcriptions of musical examples as well.

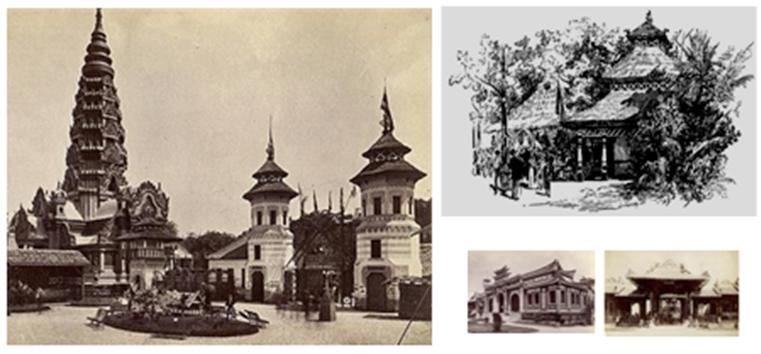

Among the most popular exhibits was the kampong, or village, of Java, with nearly a million visitors. (See Figure 2.) Its entrance featured two tall towers with double sloped pagoda-like roofs. Tents sheltered a village where some sixty Javanese inhabitants lived and carried on typical activities for all to see such as housekeeping, cooking, weaving cloth, making batiks, carving bamboo utensils, and making jewelry. Processions of villagers playing hand drums and angklung (hand held instruments of rattling tuned bamboo tubes) escorted visitors to the open-air pavilion where musical and dance performances occurred daily.7

Figure 2. Javanese kampong and nearby structures at 1889 Exposition. Left: Pagoda of Angkor Wat on left and two entrance towers to Javanese village on right. Lower middle: Palace of Annam and Tonkin. Lower right: Pavilion of Cochin Chinga. (These three in National Gallery of Art "Paris Exposition 1889") Upper right: Javanese pavilion. (In L'Exposition de Paris 1889 1: 163.)

Figure 2. Javanese kampong and nearby structures at 1889 Exposition. Left: Pagoda of Angkor Wat on left and two entrance towers to Javanese village on right. Lower middle: Palace of Annam and Tonkin. Lower right: Pavilion of Cochin Chinga. (These three in National Gallery of Art "Paris Exposition 1889") Upper right: Javanese pavilion. (In L'Exposition de Paris 1889 1: 163.)

One of the many visitors was Debussy, who returned again and again to the exhibit. Debussy's friend Robert Godet captures the composer's fascination:

Many fruitful hours for Debussy were spent in the Javanese kampong of the Dutch section8 listening to the percussive rhythmic complexities of the gamelan with its inexhaustible combinations of ethereal, flashing timbres, while with the amazing Bedayas [dancers] the music came visually alive. Interpreting some myth or legend, they turned themselves into nymphs, mermaids, fairies and sorceresses. Waving like the ears of corn in a field, bending like reeds or fluttering like doves, or now rigid and hieratic, they formed a procession of idols or, like intangible phantoms, slipped away on the current of an imaginary wave. Suddenly they would be brought out of their lethargy by a resounding blow on a gong, and then the music would turn into a kind of metallic galop with breathless cross-rhythms, ending in a firework display of flying runs. The Bedayas would then remain poised in the air like terrified amazons questioning the fleeting moment, the secrets of love and life. But they are amazons only for a moment; now they are water-spirits or birds or flower-maidens weaving festoons, or butterflies of all the colours of the rainbow. A flute run flashes out and each of the Bedayas beats its wings, or flutters its petals, and once again they come to life in rhythm paying homage to their hidden god.9

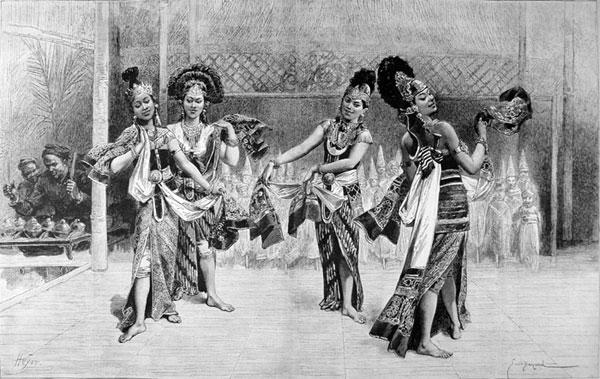

Figure 3 shows the Javanese dancers at the 1889 Exhibition. On the left can be seen a part of the gamelan accompanying them.10

Figure 3. Javanese dancer at 1889 Exposition, with gamelan in background. (In L'Exposition de Paris 1889, Supplement no. 27)

Figure 3. Javanese dancer at 1889 Exposition, with gamelan in background. (In L'Exposition de Paris 1889, Supplement no. 27)

Many visitors wanted to recall the music they had heard at the Exposition. In the days before modern recording technology, transcriptions were a common and popular means for acquaintance with music of all sorts.11 Concurrently with the Exposition, and for years after, piano transcriptions of exotic music were published and available for sale.12 Claude Debussy too remembered the Javanese music he heard at the Exposition. Elements of gamelan emerged in many of his compositions from that time onward. One particular piano piece, Pagodes, remains, over a century later, the most famous and effective gamelan in the Western repertory. Debussy wrote no transcriptions of what he heard at the Exposition. He wrote no academic treatise about gamelan music. Yet he provides us with detailed understanding through composition

Gamelan

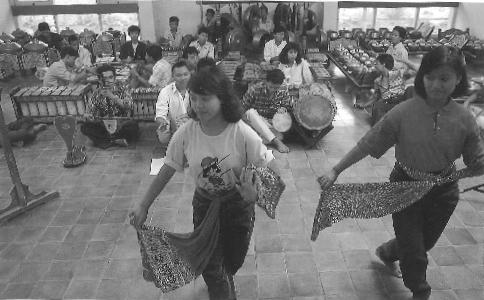

Found throughout Indonesia, the gamelan may be thought of as a percussion orchestra. Its instruments are mostly metallophones struck with mallets of various sizes, shapes, and materials. Pictured in Figure 4, they include single hanging gongs and groups of tuned gongs and bars suspended over resonator boxes and tubes.13 Their timbres are exquisitely rich, varied, and colorful. They are handmade by skilled craftsmen who measure tin and copper in special recipes to make bronze, then melt it, pour it into molds, cool it, pound, file, reheat, strike, listen, pound, and file some more. Figure 5 shows instruments in the making.

Figure 4. Modern Javanese dance class, with gamelan in background. (In Lindsay Javanese Gamelan, photo 22)

Figure 4. Modern Javanese dance class, with gamelan in background. (In Lindsay Javanese Gamelan, photo 22)

Figure 5. Gamelan instruments in the making. (In Lindsay Javanese Gamelan, photos 10-14)

Figure 5. Gamelan instruments in the making. (In Lindsay Javanese Gamelan, photos 10-14)

Their size, resonance, and means of striking naturally affect their volume and speed of note patterns playable upon them. They fall into two general categories known as "loud" and "soft." In addition to the multiple tuned percussion instruments—loud sarons and bonangs, and soft slentems, genders and gambangs—hand drums and single soft instruments enrich the ensemble: a bamboo end blown flute (suling), a two-string bowed spike fiddle (rebab), a multi-stringed plucked zither (celempung), and singers. Unlike a Western orchestra, in which players bring their own instruments upon which they are experts, the gamelan stays put and the players come to it. They join together from all walks of life, starting even in childhood, and traditionally pass on their music to each other aurally.14 Each player is competent on all of the instruments. Each gamelan has its own home and its own name, and each is revered as having special, even supernatural, qualities.15

Gamelan tuning contrasts with that of Western music. The traditional Javanese slendro scale has five pitches spaced approximately equally over the octave. Thus each interval is larger than a major second and smaller than a minor third.16 The approximate nature of the "equal" spacing creates intriguing differences between gamelans. The fundamental pitch of the gamelan is set not to a universal standard but, instead, to one chosen by its maker, often the highest note he can conveniently sing.17 In a practice that must be astonishing for Western musicians, "unison" instruments may be intentionally made slightly out of tune with each other, to produce a shimmering timbre when they are played together.18 The microtonal uniqueness of each gamelan is a part of its character, and is known and valued by Javanese players. Substituting an instrument or installing a replacement part is unthinkable. The fixed tuning of the percussion instruments may be enriched in performance by special inflections of intonation known as "vocal tones," provided by the suling (flute), rebab (spike fiddle), and singers.19 The actual music played upon the gamelan limits its focus to selected notes and ranges, resulting in three patets, akin to Western modes.20

Gamelan music is built of blended melodic layers. The manner of playing is dynamically level, and the balanced heterophony among the various melodies reflects Javanese society, in which restrained behavior and smooth interactions are valued. In a study entitled Folk Song Style and Culture, Alan Lomax describes this "Old High Culture" society as

a highly stratified world, where the fate of every individual depended upon his relationship to the superstructure above him, where he was confined within a system of rigid social stratification, and where his survival depended upon his command of a system of deferential etiquette . . . . [In music] there is a strong relationship between increase of layering . . . and elaboration. [ . . . ] Another measurement of increased social formality is orchestral complexity.21

Among the layers, a central skeleton melody (balungan) provides a guide. Even if not rendered note for note, its outline is known and expected by all the players. It moves in fairly conjunct intervals over a narrow range and in steady note values at moderate tempo. Simultaneously other instruments improvise elaborations that enrich the basic melody. Players learn short melodic patterns (cengkoks) around and between skeleton tones, and then improvise their placement into the texture during performance. The equally blended effect is unlike Western classical music, in which usually a primary melody stands out from harmony and improvisation is uncommon.

The speed or, rather, rhythmic intensity of improvisation is naturally influenced by the resonance and clarity of the instrument upon which it is played. Soft style percussion instruments are able to play quicker, more intricate patterns than loud style instruments. Specific ratios (iramas), named and known to all the players, govern the speed of the notes. Rather than defining individual time values such as quarter, eighth, and sixteenth notes, iramas instead indicate relative speeds in reference to the skeleton notes. Ratios of 2:1, 4:1, 8:1, 16:1 dictate subdivisions, each doubling the intensity of activity.

Holding together, indeed controlling, all elements of gamelan music is rhythmic punctuation known as colotomic structure. The rhythmic architecture always includes large gong phrases (gongans) and smaller phrases of exactly half and quarter length, the phrases and subdivisions always proceeding in four-beat groups (gatras). The ethnomusicologist Judith Becker explains both large structures and elaborative subdivisions relative to Javanese philosophy:

This regularity and order . . . reflects the orderly universe. Traditional gamelan music both sanctioned and was sanctioned by heaven, resulting in a musical conservatism manifested by the rigid adherence to four-beat units, which may be either multiplied or subdivided, . . . a musical relationship that has remained fixed for a thousand years or more.22

Endings provide the most important rhythmic events in gamelan music (not beginnings, as in the Western downbeat). The endings of a whole piece and its most important sections are marked by the largest gong (gong ageng), whose deep rich timbre resonates with all of the overtones of the other instruments.23 Smaller gongs punctuate the endings of intermediary sections. Of various sizes, shapes, and sounds, their names are onomatopoeic—ketuk, kempul, kempyang, kenong, gong.24 Each player is constantly aware of the colotomic structure and always expects the arrivals of the appropriate gong markers at the ends of phrases and sections. At the very end, players all listen attentively for the gong ageng and even adjust the timing of their own final notes in deference to it. Arrivals of endings require ritards in preparation. Changes in iramas require changes in tempo to accommodate more or less rhythmic activity. These tempo changes are usually directed by hand drums (in loud style) or by the rebab (in soft style). Players all listen for rhythmic cues rather than visually following a conductor.

Pagodes

The preceding overview summarizes the basic elements of gamelan music as documented by twentieth-century ethnomusicologists.25 Claude Debussy summarizes his own impressions of gamelan in 1913:

There used to be—indeed, despite the troubles that civilization has brought, there still are—some wonderful peoples who learn music as easily as one learns to breathe. Their school consists of the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, and a thousand other tiny noises, which they listen to with great care, without ever having consulted any . . . dubious treatises. Their traditions are preserved only in ancient songs, sometimes involving dance, to which each individual adds his own contribution century by century. Thus Javanese music obeys laws of counterpoint that make Palestrina seem like child's play. And if one listens to it without being prejudiced by one's European ears, one will find a percussive charm that forces one to admit that our own music is not much more than a barbarous kind of noise more fit for a traveling circus.26

Debussy presents his impressions even more clearly in his 1903 composition Pagodes. It is the first in a set of three pieces entitled Estampes,27 meaning stamp, or in the world of visual art, a print made by pressing a carved block into ink and then stamping it onto paper. In Pagodes he presents an aural rather than visual print of the gamelan.

His choice of title has puzzled many scholars, since Java actually is not a land of pagodas.28 Debussy's ongoing fascination with oriental art (especially Japanese woodcut prints), his re-exposure to the gamelan at the 1900 Exposition Universelle, and the recent return of a friend from a trip to China and Vietnam may all have provided him with general reminders of the Orient while he was composing Pagodes.29 Yet his specific choice of title remains a mystery. A solution to the puzzle might be found in observing, as Debussy would have, the pagoda-like towers at the entrance to the Javanese village, the pagoda of Angkor Wat right next door, and the many curved pagoda-appearing roofs in the vicinity at the 1889 Exposition. (See Figure 2.)

Significantly, Debussy chose the piano as his medium. He was a fine pianist himself, trained in the traditional concert repertory during his student years at the Paris Conservatory. He had also developed considerable mastery in orchestral composing, with its consequent attention to instrumental timbres. During the decade or so beyond schooling his concept of the piano seems to have evolved from the nineteenth century ideal as a "singing" instrument to that of a "coloristic" instrument. Pagodes is his first piece to fully embrace the piano's innate percussive nature, its mechanism producing sound via hammers hitting strings.30

A marvelously sensitive pianist, Debussy often amazed listeners with the sounds he drew from the instrument. Several of his contemporaries have commented on this aspect of his music and his playing:

The power of the magic will be understood by all who have once heard this supernatural piano in which sounds are born of the impact of the hammers, with no brushing against the strings, then rise up into transparent air, which combines but does not blend them, and evaporate in iridescent mists. Monsieur Debussy tames the keyboard with a spell which is beyond the reach of any of our virtuosi.31

No words can give an idea of the way in which he played . . . . Not that he had actual virtuosity, but his sensibility of touch was incomparable; he made the impression of playing directly on the strings of the instrument with no intermediate mechanism; the effect was a miracle of poetry. Moreover, he used the pedals in a way all his own.32

Debussy insisted upon . . . the proper way to strike a note on the piano. 'It must be struck in a peculiar way,' he would say, 'otherwise the sympathetic vibrations of the other notes will not be heard quivering distantly in the air.' Debussy regarded the piano as the Balinese [sic] musicians regard their gamelan orchestras. He was interested not so much in the single tone that was obviously heard when a note was struck, as in the patterns of resonance which that tone sets up around itself.33

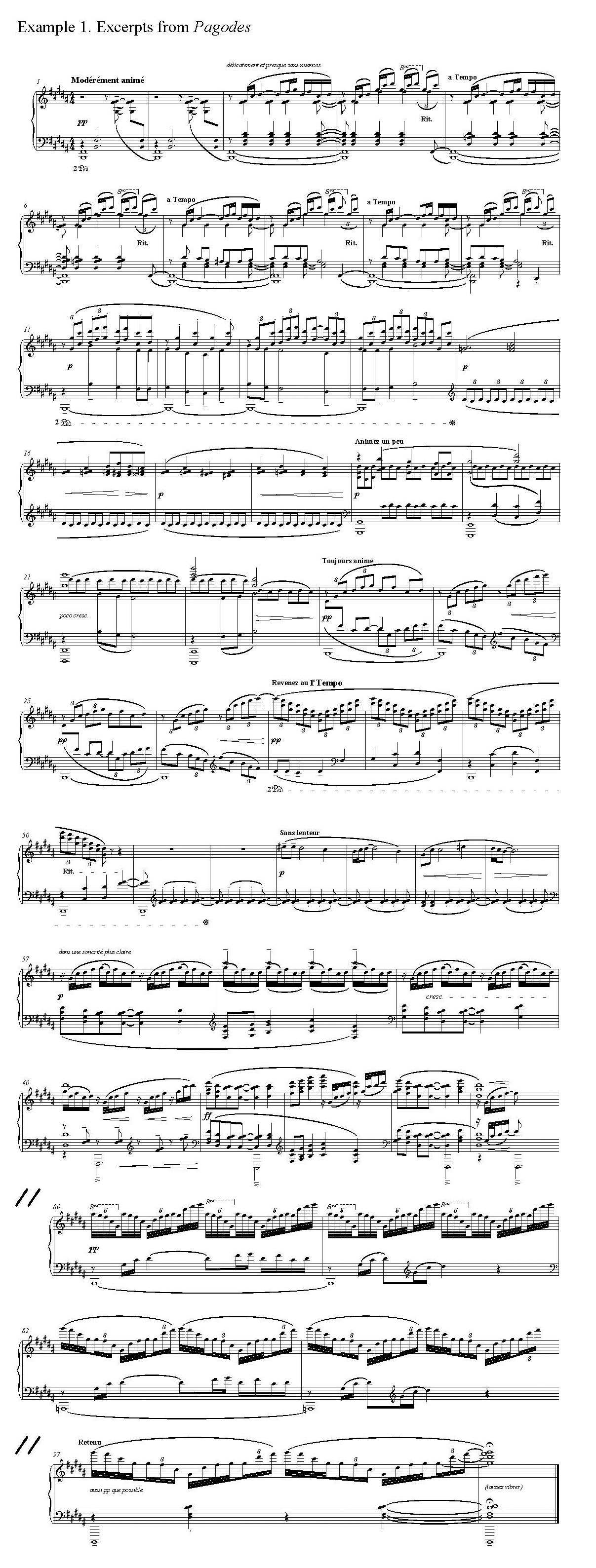

In Pagodes the piano simulates the timbre of the gamelan. The first measure (see Example 1, which contains all of the musical excerpts in the following discussion) presents a perfect fifth, low B-F#, followed by the same fifth an octave higher and a seeming discord F#-G# higher yet, all played pianissimo and all blurred together by two pedals (soft pedal and damper pedal). The result is an overtone-rich composite sound evocative of a gong. Debussy's notation in the ensuing measures of tied bass whole notes that the pianist cannot literally hold (because the hands must move to play other notes) requires the use of pedal to sustain them. In effect the gong continues to vibrate quietly through the melodic material above it. Lest the pianist attempt to clean the blurry sound, Debussy marks the continuation of pedal with dotted lines under extended passages such as mm. 11-14 and mm. 27-31.

He suggests various touches that evoke the gamelan's percussive, shimmering qualities.34 Numerous articulation markings such as slurs, tenutos, and dots permeate the score. Not marks of expression, these instead indicate how to strike the piano keys. The sound qualities achieved by differing strokes and the use of pedal resemble the sound qualities of the gamelan instruments. For example, at m. 11 the bright ping of notes struck staccato contrasts the mellow bong of those struck tenuto, thus distinguishing the timbre of the two simultaneous melodies. The Western classical meanings of sharply separated notes (staccato), stressed long notes (tenuto), and smoothly connected notes (slur), melt instead into marvelously vibrating resonances of the gamelan when engulfed in Debussy's pedals.

The piano, with its equal-tempered chromatic tuning, cannot possibly reproduce gamelan scales. But the piano's black-key pentatonic scale roughly simulates the five-note slendro: it has no half steps, and its whole steps and minor thirds approximate slendro's intervals somewhere in between. Even its two larger intervals simulate the not-quite-equidistant spacing found in slendro tuning. Debussy chooses the pentatonic scale for most of the motives and sonorities in Pagodes.35 For example, it produces the G# C# D# F# G# motifs in mm. 3, 11, and 27. A different pentatonic grouping A# C# D# F# G# appears in the upper voice at m. 15. Yet another moves to a new position B G# F# D# in m. 19. Their differing focal tones and ranges may even allude to the patets Debussy would have sensed in Javanese music.

The texture of Pagodes comprises stratified layers in the fashion of authentic gamelan music. The opening fourteen measures illustrate this. Measure 1 introduces an imaginary gong ageng, on the low B. At m. 3 a pentatonic motive begins in sixteenth notes at high register, perhaps calling to mind the timbre of a metallophone. Its agile cengkok-like pattern moves between and around notes of an imaginary skeleton that proceeds by conjunct motion in an arch up and back down. At m. 7 a central-register melody enters with a down-up arch in unadorned conjunct eighth notes, functioning perhaps as the balungan in this imaginary gamelan. The smooth contour and quietness might evoke the bowed string timbre of the rebab. At m. 11 another mid-register melody copies the stepwise down-up arching contour of its predecessor in m. 7, now in quarter notes and positioned higher in the pentatonic scale such that the "steps" are actually somewhat larger as in the slendro scale. Along with it appears another upper register rendition of the original cengkok pattern, only now in eighth notes instead of sixteenths. In sum, the first fourteen measures of Pagodes build up multiple layers in low, middle and high registers in slow, moderate and fast rhythmic activity, all layers presenting some plain or elaborated version of an arch-shaped conjunct skeleton.

The stratified effect continues throughout the piece. At m. 23 two layers present a variant of the original cengkok pattern arching in opposite directions with staggered entrances over a recurring gong. At m. 27 yet another version appears in two voices a fourth/fifth apart (constituting parallel motion within the pentatonic scale and the four-note patet in use here) in triplet eighth notes above a slower rendition in quarter notes.36 In the coda, at m. 80, a new layer appears in the fastest motion of all, thirty-second notes. The entire piece comprises stratified layers distinguished by register and rhythmic activity (and timbre in the hands of a skillful pianist), yet always blended because they all accommodate the pentatonic scale and the same arching skeleton contour.

Debussy indicates the performance style as délicatement et presque sans nuances (delicately and almost without nuance). The levelness evokes Javanese restraint rather than Western expressiveness. Those dynamic shadings marked with hairpins in the smooth melodies of mm. 15-18 and 33-36 simulate only the subtle inflections in volume that, for example, the rebab might naturally make. The balance among layers is equal, with no single part brought out over the rest of the texture. The level blending contrasts with Western performance practice, and requires careful attention on the part of the pianist not to play with an expressiveness or prominence inappropriate to the gamelan.

On the other hand, Debussy does mark differing dynamic levels at phrase boundaries throughout the score. For example, the opening ten-measure portion is pianissimo; the change to piano in m. 11 coincides with a new bass note and octave reinforcement in middle and upper layers. The passage at m. 37 is piano and its repetition at m. 41 is fortissimo. The whole coda, mm. 80-98, is pianissimo. The distinctly contrasting dynamic levels effectively simulate the gamelan's changing instrumentation, and especially the contrast between loud and soft styles.

Debussy punctuates the large colotomic rhythmic structure of Pagodes with his own gongs. The gong ageng is low B. It provides the final note of the piece (m. 98) and the culminating note of many phrases (as in mm. 5, 7, and 9). Intermediary structural punctuations are provided by other bass notes. At m. 11 the punctuating gong moves to G#. In mm. 19-23, bass notes return generally stepwise from that G# down to B once again, in one-measure time spans, half and quarter those of the earlier gongs, reflecting the orderly subdivision of Javanese gatras. The descending bass notes simulate the intermediary ketuk, kempul, kempyang, and kenong arrivals in gamelan music.37 Sensing these gongs as endings, not beginnings, may not be intuitive to Westerners. Yet an importantly different rhythmic interpretation would emerge if a bass downbeat were to energize the start of a new phrase rather than finish the preceding one.38

Debussy also captures the changing tempos that signal important events in gamelan music. For example, in the opening section of the piece he indicates a ritard just before each arrival of the low gong in mm. 5, 7, and 9. In mm. 19-33 he imitates the gradual tempo change that guides gamelan players from one irama to another. Animez un peu at m. 19 moves to Toujours animé at m. 23 as the rhythmic calmness of one passage moves toward more complex cross-rhythms in the next. Continuing the transition, Revenez au 1o Tempo at m. 27, ritard at m. 30, and Sans lenteur at m. 33 prepare for the arrival of new thirty-second note activity m. 37.39

Pagodes convincingly simulates a Javanese gamelan. Yet it does not merely copy. Within Pagodes aspects of both Eastern and Western musical thinking merge. For instance, while Debussy successfully substitutes the pentatonic scale for gamelan's slendro, the principal G# C# D# F# G# motif of m. 3 actually limits itself to only four of the pitches (appropriately, as in a Javanese patet). The missing pitch appears in the middle-register melody of m. 7, but it fluctuates between B and A#. Several possibilities arise. Perhaps these two represent the actual missing pitch in the slendro scale, which is somewhere between them. Perhaps they simulate microtonally inflected vocal tones. But perhaps they also carry Western harmonic significance irrelevant to gamelan: B is tonic and A# is its leading tone; A# then becomes dominant of the dominant as the (Western) tonality modulates from B major to the relative minor g#.

Gamelan music is entirely polyphonic, not chordal. Yet Debussy employs chords in Pagodes. How he does so reveals his sensitivity to both gamelan timbre and Western functionality. The very first chord provides an example. Its purpose in a Western sense is to establish the tonic B. But it fails to establish the B major tonic triad as one would expect in a Western context. Rather, B appears with its natural fifth F#, no third, and discordant G# a step away (actually an upper partial in the B harmonic series). The pedaled pianissimo result simulates the overtone-rich ringing of the gong ageng. Furthermore the perceived rhythm of m. 1, quarter—dotted quarter—quarter—eighth, provides not a Western syncopation but, instead, a softly resonant vibration like that of a real gong ageng, which one almost feels rather than hears.40 The vibrations continue to resonate, as does a Javanese gong, in the ensuing eight measures of offbeat quarter note chords. The chords themselves exhibit Western tonal function as well as exotic sound. The B, B7, and E chords of m. 3, 5 and 7 can be interpreted as I—V7/IV–IV in the key of B major. They lead to bass D#—G# in m. 10-11, V—i of the relative minor key. Yet it is their rich color rather than their tonal function that seems aurally more captivating as they blend into the quiet pedaled sonority.

The passage in mm. 15-18 harmonizes its arching top-voice melody with dyads and triads created from chromatic, not pentatonic, linear counterpoint. The lower two voices complement the up-down contour of the pentatonic melody with down-up nearly parallel chromatic motion (sometimes arriving at unisons single-stemmed in the score). The contrary motion and intervallic diminution in use are two venerated Western polyphonic techniques. Yet the choice of chromatic pitches in this passage contrasts with the pentatonic content of the entire rest of the piece. Timbre again suggests a possible reason: the shimmering quality of the discords subtly evokes those intentional mistunings of gamelan unisons.

Rhythmic aspects, too, complement authentic gamelan practice. For example Debussy chooses not only eighth notes, sixteenths and thirty-seconds as the counterpoint to quarter notes, whose ratios all produce the rhythmic doublings characteristic of gamelan iramas; he also chooses triplet-eighths and triplet-, quadruplet- and quintuplet- thirty-seconds, which have no place in traditional gamelan music. And these shift among each other, as in the sections at m. 11 with both duplet- and triplet-eighths, and at m. 80 where triplet-, quadruplet- and quintuplet- thirty-seconds fluctuate.41 With these superposed shifting rhythms, spread over multiple octaves, Debussy creates the illusion of complexity among many contrapuntal layers as in gamelan practice, yet composes music that is actually playable by one pianist on one instrument.

His sensitivity to the capabilities of the pianist emerges likewise in mm. 37-44.The crescendo and repeated quick cengkoks in mm. 39-40 simulate the addition of extra instruments in preparation for the loud phrase at m. 41, but the pianist is spared the technical difficulties of playing fast octaves or cross rhythms. The fragments of quick notes in mm. 42 and 44 provide the illusion, rather than the actuality, of continuing through slower ones in a fashion readily playable by the pianist.

Phrase structure and form in Pagodes furnish by Western means the necessary organization that is provided instead by gong phrases and their subdivisions in Javanese music. Pagodes' four-measure phrase lengths, common to much Western music, fit the gamelan illusion well. Even the two "extra" measures at the beginning and in mm. 31-32 can be accounted for as an allusion to the gong's prolonged ringing. Yet the Western ABA form with coda42 creates a unifying large-scale structure that is not at all characteristic of Javanese design, which is governed entirely by perfectly regular gatras. The Western classical form creates the vehicle for carrying the impression of the exotic gamelan effectively to Debussy's intended audience.43

Context

Placing Pagodes in the framework of Debussy's other works provides perspective on his evolution as a composer. At this formative time in his life, after his studies at the Paris Conservatory (1872-1884) and his time in Italy as winner of the Prix de Rome (1885-1887), the 1889 Exposition provided exposure to a completely new kind of music.

Some of his earliest compositions had already revealed experiments with non-traditional elements such as pentatonic scales, ostinato, static harmony, and stratified textures.44 Such experiments shaped a style that was not always appreciated by musical experts: Printemps, his required submission as winner of the Prix de Rome, earned him an admonishment in 1887 to "be on his guard against that vague 'Impressionism' which is one of the most dangerous enemies of truth in works of art."45

Rather than creating an entirely new style, the timbre, tuning, layering, and rhythm he found in Javanese music instead nourished elements already latent in his writing. Pagodes did not immediately follow Debussy's encounter at the 1889 Exposition. Fourteen years intervened. Those years were dominated by the composition of his opera Pelléas et Mélisande, which he says "took me twelve years to write."46 Other works of the time include the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra, begun while the Exposition was still on,47 the String Quartet, Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, Chansons de Bilitis, Nocturnes, and Pour le piano. All of these contain some elements attributable to the gamelan, yet none specifically evokes one.

Pagodes of 1903 is the first of Debussy's piano compositions alluding to the Orient, and the first that represents the Impressionistic style for which he is today admired. His friend Robert Godet recalls those intervening years:

At first, in the three or four years [sic] that passed between the Exposition of 1889 and the publication of Pagodes (first date, barring error, of the works bearing the imprint of "exoticism") one had the occasion to submit to the composer numerous documents collected in diverse places of Asia and the Islands of Sonde [now Indonesia], this in devout care to "orient" (this is for once the correct word) his memory or fantasy.48

Significantly, the same time frame, 1903-05, also saw the composition of La Mer for orchestra, Debussy's one other work that alludes specifically to the gamelan.49 Beyond that time characteristics inspired by the gamelan—timbre, exotic scales, layering, rhythmic design—appear in virtually all of Debussy's mature works.50 His revolutionary treatment of the piano, stemming from its percussive rather than its singing nature, has led to some of the most important music in today's piano repertory.

Conclusion

In the century-plus since its composition, Pagodes has provided enjoyment to countless listeners and performers, and material for study to myriad analysts.51 The influence of Javanese gamelan extends far beyond Debussy as well. Works by composers after him as diverse as Ravel, Bartók, Poulenc, Britten, McPhee, Eichheim, Cowell, Cage, Harrison, and Reich all owe inspiration to the gamelan.52 Today we can readily access recordings, pictures, and scholarly writings about gamelan music provided by more than a century's roster of ethnomusicologists. Debussy's sole source of exposure was the Javanese music at the Paris Expositions Universelles. For him there were no research documents to read, no instruction in how to play the instruments, and no travel to Java. Yet he clearly absorbed the elements of gamelan music that ethnomusicologists have documented. Without endeavoring to explain these elements, he instead incorporated them into a gamelan of his own making, one created for Western listeners and performers.

A year before its composition he wrote that music "is not limited to a more or less exact representation of nature, but rather to the mysterious affinity between Nature and Imagination."53 Pagodes is not a transcription, not an exact representation of nature. It is an imaginative creation. Arguably his first Impressionistic composition for piano, Pagodes presents not some vague impression but, instead, a remarkably accurate and evocative rendition of the Eastern gamelan on the Western piano.

Bibliography

Abravanel, Claude. "Symbolism and Performance." In Debussy in Performance, edited by James R. Briscoe, 28‒44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Becker, Judith. Traditional Music in Modern Java. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1980.

Bellman, Jonathan, ed. The Exotic in Western Music. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998.

Benedictus, Louis. Les Musiques Bizarres à l'Exposition. Paris: G. Hartmann, 1889.

Born, Georgina, and David Hesmondhalgh, eds. Western Music and Its Others. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Brandon, James R. On Thrones of Gold. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1970.

Brinner, Benjamin. Knowing Music, Making Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Briscoe, James R., ed. Debussy in Performance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Casella, Alfredo. "Claude Debussy." The Monthly Musical Record 63, no. 2 (1933).

Cooke, Mervyn. "The East in the West: Evocations of the Gamelan in Western Music." In The Exotic in Western Music, edited by Jonathan Bellman, 258‒80. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998.

Cortot, Alfred. "La Musique pour Piano de Claude Debussy." La Revue Musicale 1, no. 2 (December 1920): 127‒50.

Dawes, Frank. Debussy Piano Music. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969.

Day-O'Connell, Jeremy. Pentatonicism from the Eighteenth Century to Debussy. Rochester: Rochester University Press, 2007.

______. "Debussy, Pentatonicism, and the Tonal Tradition." Music Theory Spectrum 31, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 225‒61.

Debussy, Claude. "Why I Wrote Pelléas" (1902). In Debussy on Music, edited by François Lesure and Richard Langham Smith, 74‒75. NewYork: A. A. Knopf, 1977.

______. "Taste." SIM 15 (February 1913). Reprinted in Debussy on Music, edited by François Lesure and Richard Langham Smith, 277‒79. NewYork: A. A. Knopf, 1977.

______. "What Should be Done at the Conservatoire?" Le Figaro (14 February 1909). Reprinted in Debussy on Music, edited by François Lesure and Richard Langham Smith, 236‒39. NewYork: A. A. Knopf, 1977.

Devriès, Anik. "Les Musiques d'extreme-orient a l'exposition universelle de 1889." Cahiers Debussy 1 (1977): 25‒37.

Fauser, Annegret. "Alterity, Nation and Identity: Some Musicological Paradoxes." Context 22 (Spring 2001): 5‒18.

______. Musical Encounters at the 1889 Paris World's Fair. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2005.

"Gamelan." In Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamelan (accessed June 26, 2012).

Gautier, Judith. "Les Danseuses javanaises et le gamelon-goedjin." In Les musiques bizarres à l'Exposition de 1900. Paris: Ollendorf, 1900.

Godet, Robert. "En Marge de la Marge." La Revue Musicale (May 1926): 51‒86.

Harpole, Patricia W. "Debussy and the Javanese Gamelan." The American Music Teacher (January 1986): 8‒9, 41.

Hood, Mantle. "Music of Indonesia." In Handbuch der Orientalistik, edited by B. Spuler et al., 1‒27. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1972.

Howat, Roy. "Debussy and the Orient." In Recovering the Orient, edited by Andrew Gerstle and Anthony Milner, 45‒81. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1994.

Hugh, Brent. "Claude Debussy and the Javanese Gamelan." BrentHugh.com. http://brenthugh.com/debnotes/gamelan.html (June 26, 2012).

Institut, L. "Les Envois de Rome de Claude Debussy, Jugés par l'Institut." Les Arts Français 16 (1918): 92.

Kasztelan, Helen. "Debussy's 'Pagodes' and the Javanese Ketawang Cycle, or Was Debussy the First Java Jive?" Journal of Music Research 1, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 33‒39.

Keeler, Ward. Javanese Shadow Puppets. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Kopp, David. "Pentatonic Organization in Two Piano Pieces of Debussy." Journal of Music Theory 41, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 261‒87.

Kunst, Jaap. Music in Java. The Hague: Martinus Nijoff, 1973.

Laloy, Louis. "Le Musicien dans la société modern." Coemedia 25 (June 1914): 2.

Lentz, Donald A. The Gamelan Music of Java and Bali. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

Lesure, François and Richard Langham Smith, eds. Debussy on Music. NewYork: A. A. Knopf, 1977.

Lewin, David. "Some Instances of Parallel Voice-Leading in Debussy." 19th-Century Music 11, no. 1 (Summer 1987): 59‒72.

Lindsay, Jennifer. Javanese Gamelan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Locke, Ralph P. "A Broader View of Musical Exoticism." Journal of Musicology 24, no. 4 (Fall 2007): 477‒521.

______. Musical Exoticism Images and Reflections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Lockspeiser, Edward. Debussy: His Life and Mind Volume I. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1962.

______. Debussy. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1963.

Lomax, Alan. Folk Song Style and Culture. Washington, D. C.: Publication No. 88, 1968.

Malm, William P. Music Cultures of the Pacific, the Near East, and Asia. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1967.

Mueller, Richard. " Javanese Influence on Debussy's Fantaisie and Beyond." 19th-Century Music X, no. 2 (Fall 1986): 157‒86.

Nichols, Roger. The Life of Debussy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Park, Raymond Roy. "The Later Style of Claude Debussy." Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 1967.

Parks, Richard S. The Music of Claude Debussy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Pasler, Jann. Composing the Citizen. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

______. Writing Through Music: Essays on Music, Culture, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Perlman, Marc. Unplayed Melodies. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Pillaut, Léon. "Musée instrumental du Conservatoire national de musique: Le gamelan javanais." Le Ménestrel (July 3‒9, 1887): 244‒45.

Priest, Deborah. Louis Laloy (1874-1944) on Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 1999.

Ratz, L. "Danses et Marches javanaises, souvenir de l'Exposition de 1889." Le Figaro Musical 17 (February 1893): 186‒88.

Roberts, Paul. Images: The Piano Music of Claude Debussy. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1996.

Rousselet, Louis. L'Exposition universelle de 1889. Paris: Librairie Hachette et Co., 1890.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Schmitz, E. Robert. "A Plea for the Real Debussy." The Etude (December 1937):781‒82.

Sorrell, Neil. A Guide to the Gamelan. Portland: Amadeus Press, 1990.

Sumarsam. Gamelan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Sutton, R. Anderson. Traditions of Gamelan Music in Java. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Tamagawa, Kiyoshi. "The Javanese Gamelan and Its Influences on the Music of Claude Debussy." DMA diss., University of Texas at Austin, 1988.

Tiersot, Julien. Pittoresques promenades musicales à l'Exposition de 1889. Paris: Fischbacher, 1889.

Timbrell, Charles. "Debussy in Performance." In The Cambridge Companion to Debussy, edited by Simon Trezise, 259‒77. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Trezise, Simon. Debussy: La Mer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

______. "Debussy's 'Rhythmicised Time.'" In The Cambridge Companion to Debussy, edited by Simon Trezise, 232‒55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Wenk, Arthur B. Claude Debussy and Twentieth-Century Music. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1983.

Notes

1Said, Orientalism, 1.

2Dates of the five Paris Universal Expositions were 1855, 1867, 1878, 1889 and 1900. Paris has also held other expositions featuring industry, arts, colonialism, technology, etc.

3Rousselet, L'Exposition, 5.

4Fauser, Musical Encounters, 1‒14.

5Detailed examinations of musical exoticism, and of Transcultural Composing with the intent to interweave additional cultural aspects into music of the Other appear in Bellman (Exotic, ix‒xiii), Born and Hesmondhalgh (Western Music, 41), Fauser ("Alterity," 14‒15), Locke ("A Broader View," 477‒85 and Musical Exoticism, 228‒36), and Pasler (Composing the Citizen, 249‒51).

6Tiersot, Pittoresques promenades, 1‒2. Translation by author.

7Rousselet, L'Exposition, 171‒76, Devriès, "Les Musiques," 33‒36 and Fauser, Musical Encounters, 165‒83.

8Java was a Dutch colony at the time.

9Godet, "En Marge," in Lockspeiser, Debussy: Life and Mind, 113‒14.

10These four dancers were from the royal court of Surakarta in central Java. The musical instruments came from the Sunda region of Western Java. Additionally a Sundanese folk dancer performed in a different style. (Fauser, Musical Encounters, 168‒73.)

11Thomas Edison's new phonograph was on display in the Gallery of Machines at the opposite end of the fairgrounds from the Eiffel Tower. It would soon set in motion the recording industry.

12Benedictus's collection (Les Musiques Bizarres, 3‒17) contains "Procession des musiciens javanais" and "Danse javanaise" and also transcriptions of Algerian, Persian, Gypsy, Rumanian, Annamite [Vietnamese], Chinese, and Japanese music heard at the Exposition. Ratz's collection ("Danses et Marches") contains three "Danses et Marches javanaises."

13Note the dancers in the foreground of Figure 4 and their similarity to those of Figure 3.

14In the twentieth century various systems of written notation have been developed for teaching purposes and documentation.

15Sorrell, Guide, 19.

16There is also a second tuning system called pelog. It consists of seven notes rather than slendro's five, with two distinctly smaller intervals. Probably Debussy heard only slendro, not pelog, tuning. Tiersot (Pittoresques promenades) examines the tuning of the gamelan at the 1889 Exposition: its five-note scale has no semitones and is represented as do-re-mi-sol-la. He also discusses its tiny differences in tuning as compared to the Western scale, and microtonal mistunings between unison instruments as well. According to Gautier ("Les Danseuses") the gamelan at the 1900 Exposition, which Debussy also heard, has five notes and no semitones. Her document includes a piano transcription by Benedictus using only the notes D-E-F#-A-B. A third gamelan with which Debussy may have been familiar, although there is no proof (Fauser, Musical Encounters, 168‒72), was the gamelan given to the French government in 1887 by the Minister of the Interior of the Dutch East Indies and housed at the Paris Conservatory museum. The curator Pillaut ("Musée," 244‒45) describes this gamelan as having a scale notated C# D# E# G# A#, with the caveat that the intervals do not correspond absolutely with ours.

17Lentz, Gamelan Music, 16.

18Sorrell, Guide, 27.

19Capturing the subtleties of gamelan tuning in written notation is fraught with difficulties. In some systems the notes have names; in others, scale degrees have numbers: in others yet, note heads appear on a five-lined staff with clef signs S (for slendro) and P (for pelog) or key signatures that include half-sharps or half-flats; and some show wavy lines for vocal inflections. Samples may be found in Kunst (Java), Sorrell (Guide), Sutton (Traditions), Sumarsam (Gamelan), and Perlman (Unplayed Melodies).

20The selected notes emphasize those a fifth apart or, inverted, a fourth and second. (Malm, Music Cultures, 31). The three patets carry significance in the context of Javanese life and drama beyond the scope of this paper. Related discussions appear in Brandon (Thrones, 52‒53), Hood ("Music of Indonesia," 7), Sorrell (Guide, 57‒62), Sutton (Traditions, 27‒29), Keeler (Puppets, 3‒4), and Lindsay (Javanese Gamelan, 40).

21Lomax, Folk, 151‒54.

22Becker, Traditional Music, 62.

23Lindsay, Javanese Gamelan, 48.

24Sorrell, Guide, 34.

25History and descriptions of gamelan appear in varying detail in Kunst (Java), Becker (Traditional Music), Sorrell (Guide), Sutton (Traditions), Lindsay (Javanese Gamelan), Brinner (Knowing), and online at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamelan. For enriching the knowledge obtained from these sources the author thanks Jody Diamond, American player, teacher, and editor of Balungan journal, for her gamelan workshop at the University of Vermont in summer 2008.

26Debussy, "Taste," in Lesure, Debussy on Music, 278.

27The other two in the set are La Soirée dans Grenade and Jardins sous la Pluie.

28A pagoda is a towerlike multi-storied Buddhist temple built over the relics of a holy man or king. Pagodas are common in India, China, Indochina, Japan, but not Indonesia. At Debussy's time there were no pagodas in Java and even today there is only one, near Semarang, according to email to the author from Rosella Kameo, July 7, 2009.

29Howat, "Debussy and the Orient," 70 and 49.

30Dawes (Debussy Piano Music, 25), Howat ("Debussy and the Orient," 57), and Tamagawa ("Javanese gamelan," 64) briefly discuss the piano and timbre in various compositions, and Roberts (Images) writes an entire book on Debussy's piano music.

31Laloy, "Le Musicien," in Priest, Louis Laloy, 23.

32Casella, "Claude Debussy," in Trezise, Cambridge Companion, 261.

33Schmitz, "Plea," 782.

34An excellent technical description of how to achieve the desired gamelan sounds on the piano is given in Roberts (Images, 289‒92).

35Many scholars have studied Debussy's use of the pentatonic scale. Day-O'Connell (Pentatonicism) discusses the pentatonic scale's history, with an analysis of Pagodes that does not refer to gamelan. In another article ("Debussy, Pentatonicism") he discusses tetrachordal sets within the pentatonic scale in the context of plagal cadence in various works including Pagodes. Kopp ("Pentatonic Organization") contrasts and compares pentatonic organization in Pagodes and Les collines d'Anacapri. Parks (Music of Claude Debussy) examines Debussy's choice of pitch materials via set theory.

36Lewin ("Parallel Voice-Leading," 59) cites "a traditional view that parallel voice-leading was for Debussy a method of elaborating monophonic ideas, the extra voices being added for acoustic coloration or for poetic effect of some sort [including] 'Oriental.'" Day-O'Connell (Pentatonicism, 175) refers to "familiar Debussian 'organum' " and cites the tetratonic collection at m. 27 of Pagodes as "particularly apt for this polyphonic device, as the resulting counterpoint in parallel 'thirds' [sic] contains only perfect intervals."

37The descending bassline G#-B in mm. 19‒23 is analysed in Schenkerian context by Day-O'Connell ("Debussy Pentatonicism," 256‒58) and in context of a Javanese ketawang temporal cycle by Kasztelan ("Pagodes," 35).

38Mueller ("Javanese Influence," 167) states that "Rhythmic grouping in Javanese music is end-accented. The notes that fall between the gong instruments marking important metric positions in the cycle are part of an extended anacrusis that presses forward to the next gong marker." Wenk (Debussy, 56) explains that "Western art music . . . is based on movement toward a goal. . . . The normative shape for a gamelan composition, by contrast, is a circle." Trezise ("Debussy's 'Rhythmicised Time'," 246) examines "the first downbeat" as "the point of departure" in compositions other than Pagodes and cites work by Cone, Kramer, Schenker, and Salzer in the study of structural downbeat.

39The performance of such tempo changes may not be intuitive to Westerners. Howat ("Debussy and the Orient," 50) says that, for example, "the sudden ritardando in bar 30 [is] often overlooked in performance by pianists who do not understand the allusion. By Western standards it is placed illogically (hence its frequent neglect); but when taken at its word the nuance is exactly characteristic of the sudden slowing of a gamelan piece just before a new cycle."

40The gong's ringing is described as "a distinctive amplitude vibrato" in Brinner (Knowing, xviii).

41Becker (Traditional Music, 40) analyzes a 1952 gamelan piece depicting the political history of Java, in which the distressing World War II era of Japanese occupation coincides with music in 3/4 and 6/8 meters as well as poly-rhythms such as 3 against 4. She points out that "Triple meters break one of the most elemental structural rules of gamelan music, the rule of subdividing the gong cycle binarily." On the other hand, Benedictus's 1889 transcriptions of Javanese music (also seen in Fauser, Musical Encounters, 180‒81 and 207‒15) include notations of triplets and sextuplets: these, however, represent written-out ritards at cadences or changes in irama, not true subdivisions. Tiersot's (Pittoresques promenades, 39‒43) musical illustrations show uneven tuplets, such as a seven-note group, in the context of free improvisation of the rebab, again not true subdivision. More recently, Howat ("Debussy and the Orient," 48) reports that "higher instruments often allow some rhythmic improvisation from the main 'melody,' with triplet-like effects, or sounding slightly 'off.'

42Measures 1, 33, 53, 80. The A section, mm. 1‒32, encompasses the B major tonality as presented by the initial B "gong" and includes its sustained return in mm. 23‒32; thus the B section commences at m. 33. Kasztelan ("Pagodes," 34), however, suggests based on analysis of the ketawang temporal, not tonal, gong cycle that the B section commences instead at m. 23.

43The effective impression of gamelan is not so obvious to all audiences. Sorrell (Guide, 6) reports that to an Indonesian listener Pagodes does not sound like a gamelan, primarily because of the tuning. Howat ("Debussy and the Orient," 54) reports that Westerners somewhat familiar with Indonesian music view Pagodes as very gamelan-like, but that specialists strenuously deny the kinship.

44Tamagawa, "Javanese gamelan," 36‒44.

45Institut, "Les Envois de Rome," in Nichols, Life of Debussy, 41. Abravanel ("Symbolism and Performance," 28‒44) and Priest (Louis Laloy, 87‒92) discuss Impressionism in painting, the Symbolist movement in poetry, "Debussyism," and other isms among the arts.

46Debussy "What Should be Done," in Lesure, Debussy on Music, 239.

47The Fantaisie was withdrawn by the composer from its scheduled 1890 premiere, revised, first performed in 1919, and not published until 1920 after Debussy's death. Mueller ("Javanese Influence") claims specific Javanese influence within it.

48Godet, "En Marge," 58‒59. Translation by author.

49Trezise (Debussy: La Mer) devotes an entire book to analysis of La Mer, including gamelan elements.

50For an overview of all of the late works, 1908‒1917, see Park's doctoral dissertation, "The Later Style of Claude Debussy."

51Richly varied analyses of Pagodes appear in Cortot ("La Musique pour Piano," 134), Lockspeiser (Debussy, 147‒48), Harpole ("Debussy and Gamelan"), Howat ("Debussy and the Orient," 46‒54), Cooke ("East in West," 259‒62), Hugh ("Debussy and Gamelan"), and Locke (Musical Exoticism, 233‒36). Additionally Wikipedia provides an on-line overview of gamelan, Pagodes and other Western music influenced by it, and links to gamelan recordings.

52Cooke, "East in West," 258‒80.

53Debussy, "Why I Wrote Pelléas," in Lesure, Debussy on Music, 74.