Background

Evaluation is an integral component of music performance and instruction, an activity in which musicians engage at many levels, ranging from processes that are very informal and spontaneous to very formal processes that occur within highly structured settings. Informal evaluation includes activities such as the self-evaluation that occurs throughout the process of music making (constantly listening to and adjusting and/or correcting one’s performance). In contrast, a traditional jury setting in which the performer receives written feedback (and a grade) from a panel of faculty is an example of a much more formal evaluation process.

Performance evaluation in the arts presents a conundrum. On one hand, artistic performance is inherently subjective—a matter of individual taste. On the other hand, demonstrated mastery of certain technical standards is expected of students in the arts. This situation is explained in A Philosophy for Accreditation in the Arts Disciplines, a statement of the National Association of Schools of Music, National Association of Schools of Art and Design, National Association of Schools of Theatre, and National Association of Schools of Dance:

Of course, evaluation of works of art, even by professionals, is highly subjective, especially with respect to contemporary work. Therefore, there is a built-in respect for individual points of view. At the same time, in all of the arts disciplines, there is recognition that communication through works of art is impossible unless the artist possesses a significant technique in his or her chosen medium. Professional education in the arts disciplines must be grounded in the acquisition of just such a technique.1

While it is likely that none of us one would deny the importance of employing fair and valid evaluation practices with our students, there is much controversy concerning just exactly how musical performance should be evaluated.

This paper explores some of the key topics related to music performance evaluation including significant political and social issues, as well as some pitfalls and concerns. The paper concludes with a discussion of selected performance evaluation tools and procedures that have been used successfully in music-performance settings.

Accountability in Higher Education

A High Stakes Political Environment

Numerous political and social forces are increasing the emphasis upon evaluating students in ways that can be documented and quantified. The legislative emphasis in the policy No Child Left Behind upon “rigorous accountability”2 has provided impetus for government mandated testing in public schools across the nation with high stakes implications in terms of rewards for schools that perform well on tests and punitive measures for those that perform below average. Now it seems that the Bush administration has expanded interest in accountability to include higher education, as illustrated by U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings’ statement in the 2006 Action Plan for Higher Education: “Over the years, we’ve invested tens of billions of dollars in taxpayer money and just hoped for the best. We deserve better.”3 According to Secretary Spellings, improved techniques for measuring achievement by college and university students “are needed to help bring important information to parents and students to help in their college decision making process . . .” and to “assist policy-makers and institutions to better diagnose problems and target resources to address gaps.”4

On March 22, 2007, the U.S. Department of Education issued the following press release:

Secretary Spellings leads national higher education transformation summit in Washington, D.C. Secretary hosts national dialogue on making college affordable, accountable and accessible to more Americans.5

The summit focused on action items around five key recommendations by the Secretary’s Commission on the Future of Higher Education to improve college access, affordability, and accountability: Aligning K-12 and higher education expectations:

- Increasing need-based aid for access and success;

- Using accreditation to support and emphasize student learning outcomes;

- Serving adults and other non-traditional students;

- And enhancing affordability, decreasing costs, and promoting productivity.

The U.S. Department of Education’s interest in creating a “robust culture of accountability and transparency throughout higher education”6 has prompted an increased emphasis upon data-driven assessment in colleges and universities across the nation.

Litigation in Higher Education: The Student as a Consumer

Growing concerns about litigation are also serving to increase university administrators’ interest in being able to quantify and document evaluations of student progress.7 An important trend that has emerged in policy and in litigation is the tendency to view the student as a “consumer”:

Education has always been a commodity to be bought and sold; the true danger lies in the move to a ‘rights-based’ culture where students (and politicians) see education merely as something to be ‘consumed’ rather than as an activity in which to participate. Whilst the law seems thus far to have been something of a bulwark against this movement, it remains an open question as to whether this will continue to be the case if Higher Education institutions do not themselves act more proactively in challenging this damaging view of education.8

For example, at my own university, we were informed in 2007 that faculty are expected to maintain records not only of final grades awarded, but also records showing exactly how those final grades were calculated. The thinking behind this, of course, is to be able to provide a defense in the event that a student contests the grade at some point in the future.

Pitfalls

Taking a consumer approach to higher education is fraught with potential problems. The argument has been made that treating students as consumers sets up a culture of entitlement that inhibits the inherent motivation to learn:

Not only are students corrupted by such a system, but faculty are, as well. They are not doing their job to impart knowledge and intellectual virtue to the students when they envision their classes as providing “customer satisfaction.” They cheat the students of the education they should be obtaining. By violating the internal goods of higher education, they are no longer acting as educators, but as clerks in an “education market”—and thus, they are behaving unethically. The consumer model even corrupts parents, if those parents call and complain about their son’s or daughter’s poor grades not from concern for the student’s improvement, but in the spirit of “doing whatever it takes” to get John or Jane through school.9

The general issue of accountability also poses challenges:

- The danger of higher education being micromanaged by outside influences for political or financial purpose, or both10;

- The negative impact on faculty and staff morale;11

- The challenge of measuring higher education outcomes in a reliable and valid manner.

However, given the political climate, it is likely that legislatively-mandated accountability will gain increasing emphasis in higher education:

Accountability literature in public administration indicates that the American political system has a long-standing, fundamental cultural norm of distrust of government and other public sector institutions. As a result, Americans and their political representatives are preoccupied with accountability and continually seek new control mechanisms to achieve it. So, the notion that accountability might just “go away” doesn’t appear very likely, especially when higher education didn’t appear to “stay tuned” to the concerns of its stakeholders and rapidly escalated tuition and other fees in the 1980s. Many of the criticisms of higher education unfortunately have some validity and the voices of the critics should be heard and actions taken to deal with them.12

Evaluating music performance in the college music setting has always presented challenges with respect to balancing the subjective, personal nature of artistic performance with the need to maintain some degree of consistency and objectivity in order to grade students fairly. In today’s political climate, and in the culture of student as consumer, music teachers more than ever need to utilize appropriate processes and tools for carrying out and documenting music performance evaluation.

Evaluating Music Performance

The art and science of evaluation involves two basic concepts: validity and reliability. The evaluation must be valid in that it measures what it is supposed to measure. (Having, for example, a student perform a series of major and minor scales might be a very valid way of evaluating certain technical skills, but it probably would not be the most appropriate way to evaluate the student’s mastery of Baroque performance practice.) In contrast, reliability relates to the consistency of the evaluation. One aspect of reliability pertains to the consistency of one faculty member's ratings (would the same performance receive the same grade at different times). In settings that involve multiple judges, such as juries and competitions, reliability can also relate to consistency across different judges. Statistically, reliability is a ratio of agreement divided by disagreement, thus, the higher the rate of agreement among different judges, the higher the reliability.

Research in music-performance evaluation has produced mixed results. Some studies have revealed that faculty evaluations of student performance may be highly unreliable13 and even biased on the basis of influences such as the time of day,14 performance order,15 and even the performer’s attractiveness, stage behavior, and dress16. Reliability tends to be quite high, however, when carefully-developed tools such as criterion-specific rating scales and rubrics are used.17

Examples of Tools and Techniques

In the language of measurement and evaluation, performance-based assessment can be a type of “authentic” assessment—authentic in that the nature of the assessment authentically reflects the nature of the instruction and learning process. However, one should not assume that all performance-based assessment is inherently “authentic.” This authenticity is only achieved when the assessment is a valid reflection of the materials and activities of the learning process. A situation in which the student spent 95% of her applied lesson time working on scales, but received a grade based solely upon jury performance of a sonatina that was prepared outside of lesson time would be performance-based, but not authentic. Performance assessments may focus upon a product (e.g., a music competition in which the quality of a particular performance is evaluated) or a process (e.g., evaluating the student’s overall musical development over time). In many cases, music teachers are interested in both a product as well as the process. In all cases, it is important that everyone involved has a clear understanding of how the evaluation is intended to function. Performance-based evaluation tends to be highly subjective. However, the use of well-designed scoring tools helps to improve reliability and validity and reduces subjectivity and bias. The three most-commonly used types of performance assessment tools are checklists, rating scales, and rubrics.

- Checklists are lists of behaviors or skills used to indicate whether each behavior or skill has been observed.

- Rating scales permit teachers to indicate the frequency or degree to which a behavior or skill is exhibited.

- Rubrics are rating scales that are specifically used for scoring results of performance assessments.

Checklists provide a quick snapshot of the student’s achievement of specific performance goals. Checklists are best when used during the early stages of the learning process to provide a quick indication of strengths and weaknesses and to provide a convenient tool for student self assessment. Figure 1 shows a simple checklist that was developed to provide feedback on piano accompaniment and song leading.

Figure 1. Piano Accompaniment and Song Leading Checklist (from Benson, 1995).

1. ____Uses correct posture and hand position

2. ____Introduces song

3. ____Cues singers to come in__(counting)

4. ____Smiles and looks up when cueing

5. ____Plays correct chords

6. ____Plays chord changes at correct times

7. ____Sings along

8. ____Uses proper balance between the hands

9. ____Plays in steady tempo throughout

10. ____Continues in tempo if chords are missed

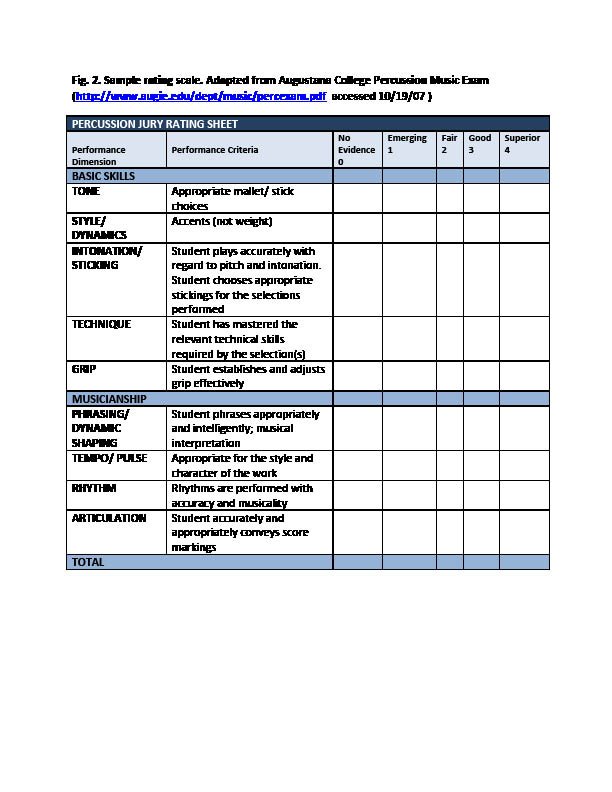

A scale is a useful tool for indicating the level of performance achievement along a continuum such as from beginning to exemplary, or from emerging to superior. Figure 2 shows an example of a rating scale for percussion. The first template contains none of these attributes—it seems illogical. I also think you need to introduce the various figures, e.g., “Figure 1 shows a generic template that can be easily adapted by an individual applied teacher’’—or something like that, and introduce the later figures as well.

Fig. 2. Sample rating scale. Adapted from Augustana College Percussion Music Exam (http://www.augie.edu/dept/music/percexam.pdf accessed 10/19/07 )

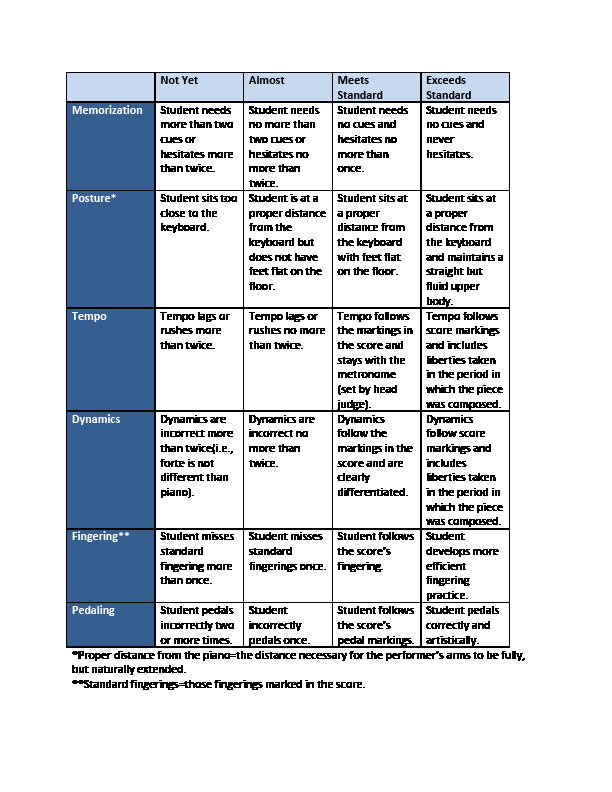

A rubric achieves the same basic purpose as a rating scale, but the rubric provides more detailed information by including specific descriptions of each level along the achievement continuum. While more challenging to develop, the level of specific detail provided by the rubric offers very useful feedback to students. A well-written rubric is also quite useful as a way of communicating performance expectations to those individuals charged with judging the performance. Figure 3 shows an example of a rubric for assessing preparatory-level piano performance.

Fig. 3. Sample Assessment Rubric for a Preparatory Piano Performance (developed by the author’s piano pedagogy graduate student)

In actual practice, music performance evaluation tools range from very open-ended comment forms to very detailed rubrics such as those used by Bands of America for adjudication of solo and group performance.18

The examples shown above were presented in order to illustrate the wide variety of music performance evaluation instruments that are currently in use. However, I do not recommend a one-size-fits-all approach to music performance evaluation, because the function of the evaluation as well as the culture of the institution must be considered. The following guidelines are offered as a first step in developing an evaluation process that works for a particular context.

Step-by-Step Guide to Developing Performance Evaluation:

- Develop a list of specific dimensions of the performance to be evaluated. This must be done collaboratively, in order to achieve consensus among all those involved in judging the performances.

- Narrow the list down to only those dimensions that are most relevant. The number of dimensions will vary with the length and complexity of the performance task. However, it is important to strike a good balance between including enough dimensions to allow for thorough evaluation and keeping the number of dimensions small enough to be manageable.

- Write clear descriptions of specific performance criteria for each dimension. Keep in mind that more specific performance criteria tend to yield more reliable evaluation results both within and between judges.

- Plan to pilot test the evaluation instrument to see if it meets the following criteria:

- Ease of use. Do judges find it effective or are some aspects confusing, ambiguous, or tedious?

- Effective communication tool. Does the evaluation instrument communicate clearly to students?

- Validity. Do students and faculty agree that the instrument measures what it’s supposed to measure?

- Reliability. Does the evaluation instrument produce consistent results?

- Make adjustments as needed and continue to monitor the effectiveness of the evaluation instrument. Do not be discouraged! It takes time and repeated trails to develop a valid and reliable music performance evaluation instrument.

While both formal and informal evaluation are inherent and essential aspects of music learning and performance, the particulars of how to carry out evaluation as well as how the results of evaluation should be used remain controversial. Regardless of how we might feel about the political overtones associated with accountability and the way that performance evaluation functions within the college music setting, we certainly can agree that a carefully-planned approach to music performance evaluation can serve as a useful tool for faculty and students.

References

American Federation of Teachers. Accountability in Higher Education: A Statement by the Higher Education Program and Policy Council. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers, 2000. http://www.aft.org/pubs-reports/higher_ed/Accountability.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Benson, Cynthia. “Comparison of Students’ and Teachers’ Evaluations and Overall perceptions of Students’ Piano Performances.” Texas Music Education Research (1995). http://www.tmea.org/080_College/Research/ben1995.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2008.

Bergee, Martin. J. “Faculty Interjudge Reliability of Music Performance Evaluation.” Journal of Research in Music Education 51, no. 2 (2003): 137-50.

Bergee, Martin J. and Melvin C. Platt. “Influence of Selected Variables on Solo and Small-Ensemble Festival Ratings.” Journal of Research in Music Education 51, no. 4 (2003): 342-53.

Bergee, Martin J. and Claude R. Westfall. “Stability of a Model Explaining Selected Extramusical Influences on Solo and Small-Ensemble Festival Ratings.” Journal of Research in Music Education 53, no. 4 (2005): 358-74.

Grantham, Marilyn. Accountability in Higher Education: Are There “Fatal Errors” Embedded in Current U.S. Policies Affecting Higher Education? Fairhaven, MA: American Evaluation Association, 1999. http://danr.ucop.edu/eeeaea/ Accountability_in_Higher_Education_

Summary.htm. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Kaye, Timothy S., Robert D. Bickel, and Tim Birtwistle. “Criticizing the Image of the Student as Consumer: Examining Legal Trends and Administrative Responses in the US and UK1.” Education and the Law 18, nos. 2-3 (2006): 85-129.

Lake, Peter F. “Tort Litigation in Higher Education.” Journal of College and University Law 27, no. 2 (2000): 255-311.

National Association of Schools of Music, National Association of Schools of Art and Design,

National Association of Schools of Theatre, and National Association of Schools of Dance. A Philosophy for Accreditation in the Arts Disciplines. Reston, VA: National Association of Schools of Music, 1997. http://nasm.artsaccredit.org/index.jsp?page=Philosophy%20for% 20Accreditation. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Potts, Michael. “The Consumerist Subversion of Education.” Academic Questions 18, no. 3 (2005): 54-64.

Ryan, Charlene and Eugenia Costa-Giomi. “Attractiveness Bias in the Evaluation of Young Pianists’ Performances.” Journal of Research in Music Education 52, no. 2 (2004): 141-54.

Spellings, Margaret. Action Plan for Higher Education: Improving Accessibility, Affordability and Accountability. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2006. http://www.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/hiedfuture/actionplan-factsheet.html. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Thompson, Sam and Aaron Williamon. “Evaluating Evaluation: Musical Performance Assessment as a Research Tool.” Music Perception 21, no. 1 (2003): 21-41.

U.S. Department of Education. Press Release. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, March 22, 2007. http://www.ed.gov/news/pressreleases/2007/09/ 03222007.html. Accessed October 12, 2007.

U.S. Department of Education. Press Release. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, September 28, 2007. http://www.ed.gov/news/pressreleases/2007/09/ 09282007.html. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Wapnick, Joel, Jolan Kovacs Mazza, and Alice Ann Darrow. “Effects of Performer Attractiveness, Stage Behavior, and Dress on Evaluation of Children’s Piano Performances.” Journal of Research in Music Education 48, no. 4 (2000): 323-35.

The White House. No Child Left Behind. Washington, DC: The White House, President George W. Bush. http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/reports/no-child-left-behind.html. Accessed October 12, 2007.

Zdzinski, Stephen F. and Gail V. Barnes. “Development and Validation of a String Performance Rating Scale.” Journal of Research in Music Education 50, no. 3 (2002): 245-55.

Endnotes

1National Association of Schools of Music. A Philosophy, 4.

2The White House, No Child Left Behind.

4U.S. Department of Education, Press Release, September 28, 2007.

5U.S. Department of Education, Press Release, March 22, 2007.

8Kaye and Birtwistle, “Criticizing the Image,” 85.

9Potts, “The Consumerist Subversion,” 63.

10American Federation of Teachers, Accountability.

13Bergee, “Faculty Interjudge”; Thompson and Williamon, “Evaluating Evaluation.”

14Bergee and Westfall, “Stability.”

15Bergee and Platt, “Influence.”

16Ryan and Costa-Giomi, “Attractiveness Bias”; Wapnick, Mazza, and Darrow, “Effects.”

17Bergee, “Faculty Interjudge”; Zdzinski and Barnes, “Development.”

18 See the Bands of America website for sample copies of detailed evaluation rubrics and forms: http://www.bands.org/public/resourceroom/adjudication (site requires user login).