Performance instruction in the United States has been taught for many years in the individual lesson setting, but recently some innovations have appeared. Explorations have been made to attempt to teach those skills in settings where there are more than one student, in groups with two to four students and in classes with five to twelve students. When an administrator wishes for such classes, he has several choices for deciding how much time the teacher can allot to them.

At the outset, the studio teacher usually has a difficult time making the transition from individual to group or class lessons. Initially, then, the administrator is wise to suggest that the time allotted for the individual lesson at his institution be multiplied by the number of students in the group or class to determine the teacher time, thereby allowing optimum time for the teacher to become familiar with managing the new setting, since his concern previous to his group/class experience has seldom been one of environment.

After the teacher has learned new teaching skills with the setting(s), it is possible to consider a reduction of teacher time for a given size group/class, because he has probably found the human and musical resources available to both the teacher and the student are substantially enriched when two or more students have their lessons together. Without any substantial information regarding the impact of reducing the amount of the teacher's time, an administrator is reduced to making arbitrary decisions based on hunches, prejudices, and hopes.

This research, conducted at the University of Colorado, provides the administrator with information to help him in his decision making. In the study a number of measures of performance outcomes were made with reduced teacher time. Although the study was made with piano instruction, there seems to be little reason to believe that the results cannot apply equally to all other performance media.

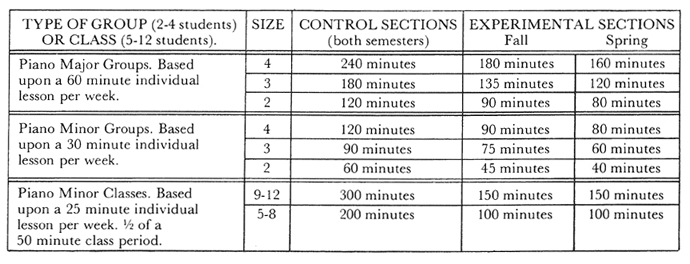

The study was conducted in two phases, coinciding with Fall and Spring semesters, academic year 1973-1974. During the Fall semester student progress in groups of two to four students was studied when the teacher time was reduced twenty-five percent. For example, four piano majors would ordinarily require four hours of teacher time at the University of Colorado, but in the Fall semester study the teacher time was reduced to three hours for the four students. At the same time, a similar research was conducted with piano classes of five to twelve students and in that study the teacher time was reduced fifty percent. For example, twelve non-piano majors would ordinarily require six hours of teaching time—one-half hour per student—but in the study the teacher time was reduced to three hours or three fifty-minute class periods. The studies during the Spring semester had teacher time for groups reduced thirty-three percent and the classes continued with half of the equivalent teacher time.

Organization of the Study

The students who were the subjects of the study of group lessons were more musically accomplished than those who were subjects of the study of class lessons. There were highly accomplished students majoring in piano included in the groups (two to four students per group) as well as other students who had up to nine years of experience. The students who participated in the piano classes (five to twelve students per class), on the other hand, were either absolute beginners or relatively new to piano instruction. Furthermore, these students were taking piano as a required course rather than as a satisfaction of an internal need of its own.

The assignment of students to groups or classes was primarily determined by 1) practical administrative requirements and 2) an audition of ability, background, and personality. The number of individuals in the experimental and control categories was more unbalanced in the Fall semester than in the Spring. The number of students assigned to each category was as follows:

| Fall Semester | Spring Semester |

| Groups | Groups |

| Experimental | 17 | Experimental | 17 | ||||

| Control | 14 | Control | 12 |

| total | 31 | total | 29 |

| Classes | Classes |

| Experimental | 52 | Experimental | 30 | ||||

| Control | 14 | Control | 27 |

| total | 66 | total | 57 |

The research design was as follows:

Groups and Classes were taught by seven teachers, including the senior author and six Doctor of Musical Arts students familiar with the problems and skills involved in utilizing group dynamic principles to facilitate learning in groups and classes. Teaching performances, organization of materials, and learning processes were coordinated and guided by the senior author with weekly conferences and periodic observations.

The instruments for assessing quality of instruction were the following.

| I. | Student Achievement |

| A. | Aliferis Musical Achievement | |

| B. | Reading at Sight1 | |

| C. | Weekly Reports |

| II. | Student Reactions |

| A. | Attitude Questionnaire | |

| B. | Course Effectiveness Questionnaire |

| III. | Grouping Instruments |

| A. | Musical-Keyboard Aptitude | |

| B. | Personality |

Before the students began classes each semester they were given the Aliferis Musical Achievement Test, auditioned and rated by teams of two and three teachers on their musical-keyboard aptitude, sight reading, and personality. In addition, students reported their attitudes toward studying piano, about multi-student settings, and how they perceived their own and their teacher's role in the teaching-learning process.

During the semester, weekly reports were made for each student by their teacher. At the end of the semester the students 1) reported on the University of Colorado Faculty Course Questionnaire, 2) repeated the Aliferis MAT and 3) repeated the Attitude Questionnaire.

Description of Instruments

The task of measuring comprehensive musicianship adequately is difficult, because all solutions are partial ones and all combinations cannot fully measure the entire concept. In this study three measures of student achievement were used, two measures of student reactions and an audition for rating musical-keyboard aptitude and personality for grouping purposes.

The student achievement instruments were the Aliferis Musical Achievement Test and a structured sight reading test, which were administered at the beginning and at the end of the semester. The third measure used was the Weekly Report made by the teachers.

The two measures of student reactions were an Attitude Questionnaire, administered at the beginning and at the end of the semester, and a Course Effectiveness Questionnaire, University of Colorado, administered at the end of the semester.

In addition to these measures of the student's achievement and reactions, supplementary measures were used before instruction began to assure that the students were placed in sections commensurate with their ability and background. An audition was designed consisting of musical-keyboard aptitude, visual perception, personality profile, and reading ability.2

Student Achievement Instruments

The Alferis MAT is a standardized, well-accepted test which tests the student's ability to recognize melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic elements and idioms. It provides a measure of the student's ability to select from musical notation items he hears played on the piano. It measures only one aspect of musical talent, auditory-visual discrimination. Its use is recommended by the authors for comparing students with national norms, for sectioning classes, and for analyzing strengths and weaknesses of individual students.

The virtues of the Aliferis MAT, its objectivity and standardization, are also its shortcomings. Such instruments must focus on the student's ability to perform technical tasks and to recognize earlier learnings. The goals of all groups and classes in this program were not focused on these informational and technical aspects of musicianship, but instead aim primarily at the development of problem creating and solving skills, willingness to take risks in exploration, and on those attributes generally associated with creativity. To obtain information on the students' performances and progress from this more holistic frame of reference, teachers and auditioners rated the students' skills several times during the semester.

The selections for Sight Reading were determined and standardized for the four levels of the curriculum used in the study. The reading performance was assessed on a four-point scale for each of the following music concepts: pitch, time, volume, articulation, tempo, form, tension-release, predominance-subordinance, scale, coordination, topography.3

During the semester the students were rated each week by their instructors on the dimensions of how well they had prepared their lessons, how much progress they had made, how much effort they displayed in class and what their attitude had been (negative, apathetic, unreliable, positive, or enthusiastic). These ratings were added to provide a total score for each semester. It should be noted that when students were absent their weekly reports were not included in the data, resulting in Fall semester of a loss of 15 students' weekly reports. Those losses were not, however, serious ones because most of them were in the experimental classes where there was an abundance of observations.4

Student Reaction Instruments

It is believed that one of the most important variables associated with effective learning of music in a group setting is the attitude with which the student approaches his work. This was not expected to be a particular problem among the students who had chosen piano as their major instrument, but it could seriously influence the learning among the students who were taking instruction because of departmental requirements rather than because of their own needs. In order to evaluate the impact of this attitudinal variable, a survey was constructed in which the students reported their attitudes toward studying piano, about multi-student setting, and about how he perceived his own and his teacher's role in the teaching-learning process.

The attitude score derived from this survey was a simple additive one, the sum of the attitudes expressed which suggested a positive attitude toward studying piano, toward multi-student settings, and an emphasis on his own responsibility to be an active participant in his own learning process. This survey was administered at the beginning and at the end of each semester.

It was anticipated that there might be teacher influences on the results of the study in ways other than simply decreasing the amount of time. It was also regarded as necessary that data be acquired which might indicate the influence of the teacher's skills and of the students' evaluation of the class as a learning experience. The University of Colorado Faculty Course Questionnaire was, therefore, administered to the students at the end of each semester.

In addition to the standard twenty-seven questions of the questionnaire, twenty-eight supplementary questions were asked. The questions deal with almost every conceivable aspect of course evaluation. They have not yet been fully analyzed except for the seven questions which have been found to represent a factor analytic labelled "course effectiveness." The questions have been found to correlate to each other highly and hence are believed to be measures of the same variable. The questions included in this factor evaluate the students' opinion about the instructor (five questions) and the course effectiveness (two questions). The "grade" given to the course by the students was computed for each student as well as for each class or group section.

Grouping Instruments

Before instruction began an audition was given to rate a student's musical-keyboard ability and discern a personality profile. A Reading-at-Sight test was given at the audition for two reasons: to assess background and student achievement at the end of each semester.

The musical-keyboard ability test had three dimensions: an aleatoric improvisation, coordination, and visual perception of pitch and rhythm. For the improvisation, the auditioner played a minute improvisation which was conceptionally oriented. For example, the performer might have started with long pitches in the high register softly and moving with an accelerando and crescendo to short pitches into the low register. The auditionee was asked to make the same kind of music without trying to repeat the organization of pitches as he heard them. The improvisation was graded with the same eleven concepts used for Sight Reading with the same four-point scale: pitch, time, volume, articulation, tempo, form, tension-release, predominance-subordinance, scale, coordination, topography.

For visual perception of pitch and rhythm, the student was asked to read from a conceptual score while making musical sense with his performance. Coordination was assessed with the playing of a simple keyboard exercise.

The personality portion of the audition consisted of the examiners' rating of the students, on a four-point scale, for thirteen personality dimensions which are believed to be important to success in the discovery learning process. Those dimensions are: enthusiasm, confidence, intelligence, intuitiveness, discipline, open-mindedness, curiosity, ability to tolerate frustration, goal directedness, motivation, objectivity, independence, and cooperativeness.

Results of the Study

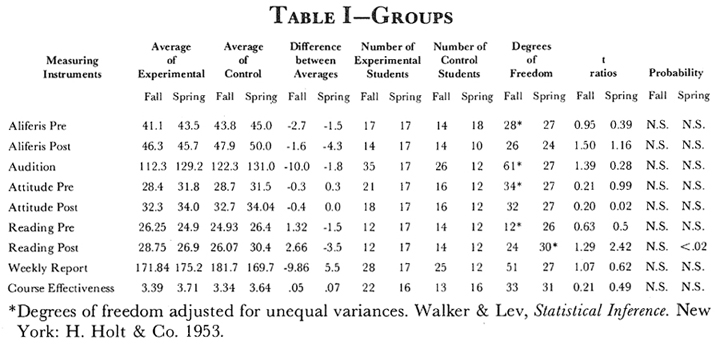

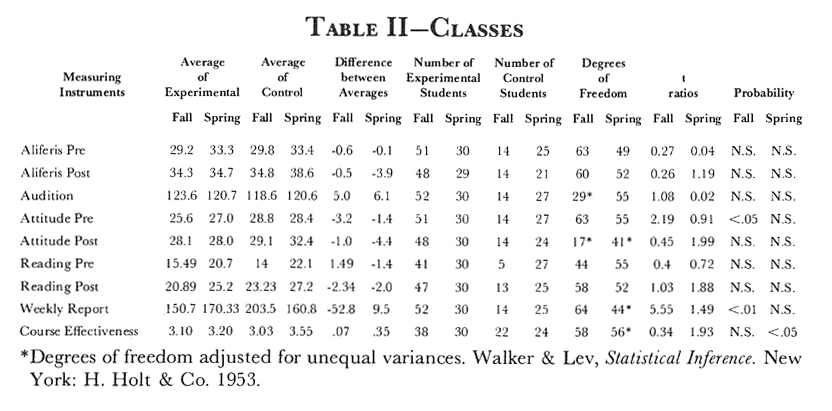

Before describing the results in detail, a brief explanation of the statistical meaning of the terms used in Tables I and II would be helpful for those who are unfamiliar with them. The measures are the arithmetic averages of the scores achieved by the students. Included in the tables are the number of students tabulated for each average. It can be seen that there is considerable variation in the number, and this was caused by incomplete data primarily for Fall semester. That is, sometimes a student did not take all the particular test or questionnaire because he was absent the day of testing.

Because no measuring instrument exists which is without measurement error, and because these averages are meant to be generalized to students in other times and places, it is expected that there will be random variations in the values of the averages. The degree to which observed differences can be attributed to these chance or random variations can be calculated. If the observed difference between the experimental and control conditions is large enough, we conclude that they do not represent random variations, but instead are caused by some influence, presumably by the experimental treatment (diminished teacher time). Column eight of the tables represents the result of this calculation, and the figures reported indicate the probability that the observed differences are the result of change. When the probability is five percent or less, it is common to conclude that the differences are not the result of chance, but are the result of the experimental treatment or of some uncontrolled variable.

Table I summarizes the findings regarding the effect of reducing teacher time with teaching groups (groups with two to four students).

It is clear that there are no differences between the experimental groups (reduced teacher time) and the control groups except the students' reading performance at the end of Spring semester, which were poorer with reduced teacher time. Whether this difference is meaningful in a practical sense rather than simply statistically significant is questionable. Nevertheless, it appears that reducing teacher time by one-third shows its effects on the degree of improvement in students' reading performance. This finding should not be interpreted to mean that reducing teacher time one-third prevents learning; both samples improved their reading skills each semester. Improvements were made on the Aliferis MAT during both semesters, also. Thus, it appears that neither semester was wasted for the students, though when teacher time was reduced one-third the students did not improve as much as the control sample.

Table II summarizes the findings regarding the effect of reducing teacher time with teaching classes (classes with five to twelve students).

It can be seen that during the Fall semester the control classes received significantly higher scores on weekly reports than the experimental classes (those with reduced teacher time) and that the students' attitudes at the beginning of the semester were poorer than the attitudes of the control classes. However, those differences failed to persist during the Spring semester, suggesting that the observed differences were not due to the experimental variable, that is, reduced teacher time.

As regards the significant difference in course effectiveness, it is clear that students in groups of more than four do not rate the effectiveness of their class as highly as when they are in smaller groups. The obvious interpretation of this finding would be that the students resist what appears to be diminished individual attention. This may be a reaction to their expectations more than to an actual need for attention. Since all of the other measures of learning indicate that there is no serious decrement, the students apparently are not rating effectiveness on the basis of how much they learned.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings suggest that teaching time can be reduced by as much as one-third for groups of two to four students and it can be reduced by as much as one-half for classes of five to twelve students without a serious decrement in learning.

Discussion

Inasmuch as time allotments for all media of performance instruction on an individual basis are uniform for all media, there is every reason to believe the findings of this study on reduced teacher time for group and class instruction are applicable to all applied music education as well as for piano.

The reader is to be cautioned, however, that the results of the study, although favorable for reducing teaching time one-third from the optimum time allowed for any given size group and one-half for a class lesson, should not be construed to mean that a teacher accustomed to teaching applied music on a one-to-one basis can continue with the teaching posture usually associated with this environment.

On the contrary, the dynamics that are available within a group setting dictate a specific organization of materials as well as a process for their delineation. A balance of integrative and dominative patterns exerted by the teacher on the group or class is necessary to take full advantage of the kinetic energy available in a group or class when individuals meet to accomplish a common goal. Further, a balance of these teaching patterns demands an organization of materials that emphasizes an inductive approach to learning.

Sometimes called Problem Solving, Discovery Learning, or Heuristics, the environment the teacher must create needs to be one of incidents or problems that interest and challenge the individuals in the group or class, causing them to investigate their own areas of concern. Under these circumstances, each individual needs first to define his understanding of the problem as it fits his unique experiences, then to locate principles and concepts which aid him in solving the problem. The principles and concepts gleaned from solving the problem become the major interest of the individual because he finds them useful in solving additional ones. As a result, information emerges out of principle and concept formation—that is, fingering, pitch names, time values—and retains its perspective in relation to all forms of performance, that is, reading, improvising, playing by ear, transposing, memorizing.

Generally, the rhythm of the teacher's use of integrative and dominative patterns is dictated by the progress the group makes toward solving a problem. The teacher initially exerts Direct or Dominative controls on the group or class with a design of tasks that are sufficiently fertile with principles and concepts. He moves into Indirect or Integrative controls when each individual begins to struggle for the principles and concepts which aid him with the problem. As the group moves from frustration toward satisfaction—a shift from awareness of problem, through principle and concept formation, toward factual data—the teacher gradually shifts his teaching posture back toward Direct controls.

Any modification of teacher behavior and organization of materials as herein described limits the productivity of the group and lessens the beneficial impact of the environment upon the individual. If teacher behavior and organization of materials remain the same in the group or class lesson as is generally associated with the individual lesson, the findings of this study become invalid, since the results of the study cannot be generalized for all teaching postures.

1This instrument was also used as part of the Grouping Instruments.

2This is the same test listed under Student Achievement Instruments.

3If the student was a beginner, there was no rating.

4This loss was prevented during Spring semester by assigning for the absent week(s) the same score the student received the week of his return.