What is music? What does it require to understand music? To these questions one might answer, "Very basically, music is an aural art; to learn to understand it, one must study with one's ears." To further elaborate, one might say, "Using our ears, together with our cognitive and creative tools, we may begin to discover the nature of this essentially aural phenomenon called music. If we go far enough, we might begin to grasp the nature of the musical experience in its entirety; and when we grasp that nature, we may then say that we understand what music is."

Historically, there have been many efforts to design courses of study to help students realize, and reap the fruits of, the musical experience. Because, in my judgment, the approaches resulting from these efforts have been less than satisfactory, I offer what follows as another, possibly more satisfactory, alternative. I do not pretend that the ideas set forth below are original; they have come from varied sources. But this does represent an effort in bringing these ideas together in an approach to teaching music to the general student.

This approach requires active musical inquiry on the part of the students. The task of the teacher is to facilitate the students' participation and to help direct their inquiry. This approach allows the teacher to accommodate students without previous musical experience as well as those who have had some musical training. The approach is one in which all students work either independently or in small groups, so that each student assumes responsibility for a large part of his or her learning. The course is based on two assumptions: first, that there are four dimensions to the comprehensive musical experience—composing, performing, listening, and evaluating; and second, that the comprehensive musical experience can be understood only through direct participation in these four dimensions. In this approach, students compose music, making legible scores, both individually and in small groups. The scores are performed in class by members of the class (and by visitors, on occasion), with the other members of the class serving as an audience. The performances are tape-recorded for future evaluation. Some students may take advantage of this opportunity to construct their own instruments.

Students investigate and explore both conservative and radical compositions of various styles, genres, and eras, observing their similarities, differences, and their unique contributions to the development of music. Students write descriptive and evaluative essays, synthesizing their knowledge and skills.

Any visual reinforcements are kept to a minimum; in fact, they are discouraged. The position taken here is that our concern is with music, and that visual "reinforcements" serve only as crutches on which listeners lean in their pursuit of understanding the musical experience. (The use of scores serves practical performance and compositional functions only.) Our culture has always emphasized the visual aspects of experience at the expense of the aural aspects. This emphasis has served to allow for the development of visual perception and concentration to the detriment of aural perception and concentration. Proponents of the "visual reinforcement" of musical learning claim that such reinforcement helps students to better understand the aural experience. They cite the dominance of visual experience in our lives (books, television, movies, theater, etc.) as evidence to support their position. Of course, this only "proves" that we have decided to make visual experience dominant. If visual abilities can be developed without aural reinforcement (and they can be), why do we need visual reinforcement for the aural experience? The answer, of course, is that we do not. We simply need to pursue aural perception as diligently as we have relied upon visual perception.

Our course under consideration may be outlined, briefly, as follows:

| I. | COURSE TITLE AND DESCRIPTION |

| Music as a Creative Experience. Students experiment with various ways of creating musical sound-structures, and engage in active, critical listening as a means to a better understanding of the nature of musical experience. Not historically oriented. | |

| II. | COURSE RATIONALE |

| The purpose of this course is to help the general students develop sensitivity to music as an art through their involvement in the experimental creation and performance of music, and in active critical listening and discussion. The course is based on two assumptions: 1) the fact that there are four ways to participate in the musical experience—composing, performing, listening and evaluating; 2) the logical theory that the best way to understand the musical experience is to participate in all aspects of that experience. | |

| III. | COURSE OBJECTIVES |

| By the end of the term, students will be expected: |

| A. | to be able to 1) perceive and recognize the structures and shapes of varied musical compositions, 2) perceive, identify, and observe the development of musical ideas in musical compositions, 3) perceive, recognize, and distinguish the various means of sound organization, 4) compose musical compositions having varied structures and shapes, 5) compose musical compositions based on varied modes of rhythm and pitch organization, 6) discuss musical compositions from both analytical and critical points of view, 7) evaluate critical writings and statements; | |

| B. | to understand how 1) musical compositions are the result of qualitative sonic thought, 2) musical compositions are structured or "shaped," 3) musical ideas are employed by composers as "subject matter" to effect musical continuity, 4) varying sonic-energy configurations in musical compositions cause affective responses in listeners, 5) composers have as their goal one object: the "shaping" of sound for the purpose of expression, 6) composers employ various means of sound organization. |

| IV. | TOPICS COVERED |

| Musical inquiry: an approach to listening | |

| Understanding the compositional process | |

| Music as an art | |

| Musical evaluation | |

| Musical style | |

| Historical considerations | |

| Musical criticism |

Since visual reinforcement is kept to a minimum, no textbook is used in this course. The following hypothetical dialogues are actual transcripts (though slightly edited) of real-life class sessions, and are provided to give insight into the procedure used in the course. It will be clear that students learn what they need to know as they need to know it, rather than reading and memorizing a good deal of useless information.

HYPOTHETICAL DIALOGUES

First Class Session

| Student: | The fact that we are expected to be able to compose concerns me. I don't know anything about music. |

| Teacher: | Your concern is understandable. I am sure that musical composition appears to most of you as an esoteric and difficult endeavor. But you know quite a bit about music—more than you imagine. Let me ask you all a question: What do you hear when you listen to music? |

| Student: | One hears many things. I really don't know how to answer the question. |

| Teacher: | O.K. I'll be more specific. What is the most fundamental thing you hear when you listen to music? |

| Student: | Sound? |

| Teacher: | Yes. Now, what kinds of sounds do you hear? |

| Student: | Sounds of different instruments. |

| Teacher: | How do you distinguish one instrument from another? |

| Student: | They sound different from one another because they are played differently and made of differing materials. In other words, some are blown into by various methods, some are bowed and plucked, some are struck. Some are made of wood, some of metal. |

| Student: | Also, some instruments are larger than others and they differ in basic construction. |

| Teacher: | So what all of you are saying is that the basic construction, material, and size of a particular instrument, along with the method of producing its sound, cause it to sound different from all other instruments. These things give it a characteristic quality, "tone-color" or "timbre." Now, what else do you notice about the sounds you hear in musical compositions? |

| Student: | They may be loud or soft. Or even somewhere in between. |

| Teacher: | How are such changes in amplitude controlled in a musical composition? |

| Student: | The performer may simply play louder or softer by using more wind pressure, bow pressure, or whatever it takes. |

| Student: | Or, it can be controlled by the types of instruments being utilized. For example, all other things being equal, trumpets will sound louder than flutes. |

| Teacher: | So there may be some relation between loudness and timbre? |

| Student: | Yes, there may be. It seems that these two elements frequently are used to complement each other. I can think of one example now. |

| Teacher: | Good. We'll be exploring several compositions featuring this relationship. Keep your piece in mind and we'll consider it also. Are there any other means of controlling amplitude? |

| Student: | Loudness can be controlled electronically. It happens all the time in rock music. |

| Student: | Electronic music, too. |

| Teacher: | Are there any other means of controlling amplitude? |

| Student: | I can't think of any others, but the three methods already mentioned are frequently used in combination. At least the first two are. |

| Teacher: | O.K. Let's see if we can come up with some other things you already know about music. What can be done to sound to make a musical composition? |

| Student: | Some sounds are higher than other sounds. |

| Teacher: | Right. When we talk about sounds being high and low, we're discussing a phenomenon which physicists and musicians call "pitch." Pitches that we call "high" have more vibrations per second than pitches we call "low." What kinds of pitch organization do you hear when you listen to a composition? |

| Student: | I don't understand the question. |

| Teacher: | How might these high and low pitches be arranged? |

| Student: | Some pitches, or groups of pitches, may be closer together than others. |

| Teacher: | Yes. There are two basic modes of pitch movement: 1) conjunct and 2) disjunct. When the pitches succeed one another by step (demonstrates at the piano), the pitch movement is conjunct. When the pitches succeed one another by skip (again, a demonstration at the piano), the pitch movement is disjunct. |

| Student: | But the two types of movement aren't mutually exclusive, are they? In other words, they are used together in combination. |

| Teacher: | Yes. Most of the time, both conjunct and disjunct movement are used—side by side. Comparatively few pieces have all conjunct or all disjunct pitch movement. What else can you say about pitch? |

| Student: | Some pieces of music have wider pitch ranges than others. |

| Teacher: | Tell the class what you mean by "pitch range." |

| Student: | The distance between the highest pitch and the lowest pitch in a composition is its range. Some pieces have wider ranges than others. |

| Teacher: | Right. (Demonstration at the piano.) |

| Student: | Pitches are sounded together, too, to make chords. |

| Teacher: | Yes. Actually, the various means of pitch organization may play a major role in shaping the character of a piece. But these will be discussed later in detail. In what other ways is sound controlled in musical compositions? |

| Student: | What about rhythm? |

| Teacher: | Could you use a term that's more fundamental than "rhythm"? |

| Student: | I don't understand what you mean. |

| Teacher: | I guess the term rhythm is quite fundamental, but it's complicated by other concepts, and its meanings are varied. |

| Student: | Duration. |

| Teacher: | Good. At this point in our inquiry this term is easier to deal with, at least for me it is. What can we say about duration in music? |

| Student: | Timbres and pitches are sounded for varying lengths of time. |

| Teacher: | Of course you're all right. Let's call these discrete durations of sound and their groups "events"—musical events—or sections, depending on the lengths of the pitch configurations. The economy of definitions will grow more important as we progress in our inquiry. |

| Student: | Sometimes, in a composition, there are several events of varying durations occurring simultaneously. Sometimes—I guess many times—some of the timbres and pitches, or their groupings, might overlap. |

| Teacher: | Excellent observation. Can you think of anything else as far as rhythm is concerned? |

| Student: | Sometimes there is more rhythm in one piece, or section of a piece, than in another. |

| Teacher: | Do you mean there is more happening, more notes, more activity? |

| Student: | Yes. |

| Teacher: | Well, we could go on. But now do you see that you know more about music than you realized? All that's needed is to give some form or organization to what you already know and add to it. |

| Student: | But what we have discussed is very elementary, very basic. |

| Teacher: | Right. But remember, this course is about learning these very fundamental concepts and adding to that knowledge, both in breadth and in depth. This is what we're about. |

| Student: | But I still don't understand how we're expected to compose when we don't know anything about putting it down on paper. |

| Student: | Yeah, won't we have to learn notation before we can compose? |

| Teacher: | The answer is no. This may sound strange to you, but notation is not music, or even musical organization. Musical notation is simply a visual representation of organized sounds (and silences). A system that any of you might devise may be as effective as the traditional system. By the way, one of the requirements for your first composition is that you make a "score" for your piece—a score that will communicate to any other member of the class. For this first assignment, traditional notation is not acceptable. All you have to remember is that a musical score simply is a set of directions for a performer to make a "sound piece." That's what music is—sound. It is not the "scribbling" on a score. |

| Teacher: | Let me illustrate one very basic approach to composing—shaping sound—through this miniature composition. |

QUARTET

| Clarinet | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Flute | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Piano | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Horn | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Instructions: | Each square represents a time frame of approximately 3 seconds. The number in each square represents the number of notes to be played in a particular 3 second period. The conductor should indicate the beginning of each 3 second time frame. |

(Piece is performed by students brought to class by the teacher.)

| Teacher: | What observations would you like to make? |

| Student: | It's interesting that some sound parameters are controlled, while others are not. For example, the basic timbres and their order of appearance are controlled and determined. |

| Teacher: | Anything else? |

| Student: | The thickness of the sound is controlled too. The piece becomes more dense as the instruments enter one by one, and as the rhythmic activity, controlled by the number of notes per time frame, increases. Then the texture thins out somewhat near the end. |

| Student: | Of course, the basic time of the piece is controlled because it's designed to last for 42 seconds and obviously the initial entrances of each instrument are timed. But the rhythm patterns, the configurations which the various instruments play, are not predetermined. |

| Student: | The notes they played weren't predetermined either. In other words, there are no pitch controls. Therefore, there is no melody. |

| Teacher: | All right, I think that is sufficient discussion of this piece. We are at the end of the period. Please keep in mind that this score could be made more determinate by specifying pitch, rhythmic configurations, and loudness. The score, then, would be more detailed and elaborate. This is just one way of making a score. Don't let this one overly influence your procedures. You must come up with sounds you want first, then determine the best means to represent those sounds on paper. A preconceived idea of a score should not influence your musical composition; the composition should influence the making of the score. |

(End of first session)

Second Class Session

| Teacher: | At the last class session, we explored some of the means by which sound is structured or shaped. Listen to the piece you are about to hear and describe, in very general terms, how its composer has organized the various sound parameters. |

(Class listens to a recording—mythical piece.)

| Teacher: | All right, class, let's describe what we heard. Who's first? |

| Student: | What did you want us to listen for? |

| Teacher: | For whatever you heard. I'm not fussy. What did you hear? |

| Student: | But we don't know what you want. I heard many things, but I don't know what you're looking for. |

| Teacher: | What was the first thing to catch your attention? |

| Student: | The volume. It was quite loud. |

| Teacher: | Did the piece continue at that same volume level? |

| Student: | No. It varied. |

| Student: | Yeah. There were three or four different volume levels. |

| Teacher: | Can you be exact about the number of levels of loudness? It's important in describing this piece. |

(Silence)

| Teacher: | After a while we'll hear the piece again. When we do, pay particular attention to the role that amplitude plays in the piece. Determine the number of amplitude levels and how the composer achieves the changes. What else did you hear? |

| Student: | Various timbres. |

| Teacher: | How many? What was the performing medium? Was it a rock group? Symphony orchestra? String quartet? Jazz ensemble? |

| Student: | I heard drums and other instruments. And a piano. |

| Teacher: | What "other" instruments? |

| Student: | I don't know what they were. |

| Teacher: | What kinds of instruments were they? Winds? String? Percussion? |

| Student: | I heard a piano and several percussion instruments—chimes, xylophone, drums, wood blocks, triangle, and a few others. |

| Teacher: | You used the term "percussion." Will you define percussion instruments for the class? |

| Student: | Percussion instruments are those instruments whose timbres are produced by striking. |

| Teacher: | Fine. What are wind instruments? |

| Student: | Instruments whose sounds are produced by the performer blowing into them through a mouthpiece. |

| Teacher: | How many classes of wind instruments are there? |

| Student: | Two. Brasswinds and woodwinds. |

| Teacher: | How do they differ? |

| Student: | Brasswind instruments have cup mouthpieces; woodwinds are played by means of reeds or a tone-hole, as on the flute. |

| Teacher: | What other instruments are normally used in western music? |

| Student: | Strings. These are instruments whose timbres are produced by bowing or plucking strings: violins and others. |

| Teacher: | O.K., now let's get back to our main point. The piece you just listened to was one involving percussion instruments and the piano. Did you notice anything about the employment of these various timbres? |

| Student: | Sometimes the percussion instruments blended with the piano. And sometimes, I guess more often, they were used in contrast against the piano. |

| Teacher: | Did you notice anything else? For example: was there a relationship between loudness and timbre? |

(Silence)

| Teacher: | Let's change the direction of our inquiry for just a moment. Was the piece in sections? In parts? If so, how many parts did you hear? Or was it simply a one-part piece? |

| Student: | I think it was in three parts. Yes, I think there were three distinct sections. |

| Teacher: | How were these sections delineated? |

| Student: | I don't understand what you mean. |

| Teacher: | In other words, how did the composer shape or structure sound so that listeners would hear the piece in three parts? |

| Student: | I'm not sure, but I am sure there are three parts and when we hear the piece again I think I'll be able to answer the question. |

(The piece was played again and the class finally described it as shown in the chart below.)

BASIC DESCRIPTION OF THE MUSICAL COMPOSITION

| Part I | Part II | Part III | |

| Soft | Medium Loud | Medium Loud | |

| Low degree of Rhythmic Activity | High degree of Rhythmic Activity | High Rhythmic Activity | |

| Mostly low notes | Mostly high notes | Mostly low notes | |

| Smooth Articulation | Mixed Articulation | Smooth Articulation | |

| Strings and Woodwinds | Full Orchestra | Full Orchestra | |

| Teacher: | This is a rather fundamental and somewhat superficial description, but it is a good indication of what musical inquiry is all about. We could say quite a bit more about this piece, but we shall inquire more deeply as we go along. From this session, several things should be apparent. 1) You can learn from each other as well as from the teacher. 2) In order to listen intelligently, you need not be told what to listen for. You may simply describe what you hear. 3) Composers shape and structure sound. 4) The intelligent and viable course to inquiry is one which will reveal the shape or structure of a piece to the listener. Please keep these four things in mind as we proceed through the course. |

(End of second class session)

ASSIGNMENTS

First Assignment

Using any available sound sources, compose a musical piece for at least four performers. Careful attention should be given to the selection, blend and contrasting of timbres. Loudness and time should also be controlled and varied. Be able to explain the shape or structure of your piece.

An accurate score must be presented at the time of performance and all performers provided with parts.

Second Assignment

Compose a piece utilizing two musical ideas and one of the following procedures: serialization, chance or indeterminacy, electronic technique.

The piece should be written for four or more performers.

Give careful attention to: 1) selection of timbres, 2) contrasting of ideas, 3) logical and effective connection of ideas, 4) over-all shape or structure, 5) factors contributing to unity and variety.

The piece must conform to the following scheme: Idea I (manipulations)—connecting passage, Idea II (manipulations)—transition coda.

An accurate score must be presented at the time of performance and all performers provided with parts.

Third Assignment

Compose a piece for four or more performers. The piece must evidence the use of both polyphonic and homophonic textures. Make the piece interesting by: 1) controlling, manipulating, and varying the articulations and envelopes of various sounds in the musical idea(s) or event(s), 2) effectively controlling and varying loudness, timbre, and density, 3) controlling, manipulating, and varying rhythm, and 4) carefully choosing compositional means (traditional, serial, aleatory, electronic).

A musical score of your piece must be turned in at the time of performance, and all players provided with parts.

Fourth Assignment

This piece must use a text, must employ some pitch controls, must involve at least one of the following: a) serialization of one or more parameters, b) determination of events by chance, c) improvisation, d) tape or electronic manipulation of sounds.

Number of performers is optional. Formal organization to be governed by the text. A score of your composition must be turned in at the time of performance, and all performers provided with parts.

Final Composition

Create a musical composition summarizing all the previous composition assignments completed during this semester. Your piece should manifest the following: 1) control, manipulation, and variance of time, 2) control, manipulation, and variance of timbre, 3) control, manipulation, and variance of envelope or articulation, 4) control, manipulation, and variance of loudness.

Your piece must include two musical ideas that are to be developed by utilizing at least five means of modification. Your piece must employ polyphony, but it need not be limited to this texture. Any connecting passages and endings should be carefully worked out so that they are logical and effective.

Give the piece structure or shape by appropriately controlling and varying the parameters or elements you have chosen to make your design manifest.

At least one of these compositional procedures must be utilized to some extent: 1) electronic, 2) serial, 3) chance, 4) aleatory (not improvisation).

The performance of the piece and the musical score you produce must reflect the use of such procedure.

AFTER THE FIRST COMPOSITION ASSIGNMENT

| Teacher: | That's an interesting piece. How did you go about making it? |

| Composer: | I started with the guitar, then kept adding instruments, creating "layers" so as to make the texture thicker and thicker. |

| Teacher: | Did you want the piece to become louder and louder also? |

| Composer: | Not necessarily. I was mainly concerned with the texture. |

| Teacher: | Why did you select the particular timbres that you used in the piece? |

| Composer: | Because they seemed to blend and complement each other. |

| Teacher: | Do you think you succeeded in creating the layer effect? |

| Composer: | No, not completely. |

| Teacher: | Do you know why you weren't successful? |

| Composer: | No, I know something is wrong, but I'm not too sure what. |

| Teacher: | Can someone in the class suggest where the trouble might lie? |

| Student: | Some instruments didn't add anything when they were added. Maybe they blended too much. |

| Student: | Or were too soft. |

| Teacher: | Do you think they played too softly? Or are their timbres too delicate? |

| Student: | I think the timbres are too delicate. |

| Teacher: | Composer, how could you remedy the situation? |

| Composer: | Well, I could change some of the instruments or maybe change the order in which the original instruments are added, putting the softer, more delicate ones first. |

| Student: | But I don't think that would solve the problem. As the more dominant instruments appear they will simply drown out the more delicate ones. |

| Student: | How about controlling the volume level of each instrument? |

| Teacher: | What do you think, composer? |

| Composer: | That might work. |

| Teacher: | Well, you have all these alternatives at your disposal. Just think about them for the time being. |

| Teacher: | Class, what is the overall design or organization of the piece? Was it in parts? Sections? Or was it a one-part piece? |

| Student: | Two parts. |

| Student: | No, I think it was one-part. |

| Teacher: | Does anybody have any other ideas? |

(No response)

| Teacher: | Composer, is your piece in one part or two parts? |

| Composer: | One part. I didn't do anything to delineate any sections. All of the sound parameters were controlled so that there were no phrases or sections. |

| Teacher: | Is there any main unifying element in your piece? What holds it together? What makes it a discrete piece with integrity all its own? Wait. Don't answer. Let's have the class answer that question. What is it, class? |

| Student: | Can we hear the piece again? |

| Teacher: | Yes. |

(The piece is played once more.)

| Teacher: | Now, what did you hear as the main unifying element in the piece? |

| Student: | As the instruments entered the piece one by one, they played essentially the same thing that the first instrument played. But this is not readily apparent, because the original idea is modified each time an instrument picks it up. |

| Teacher: | Is that true, composer? |

| Composer: | Yes. |

| Teacher: | Is there anything in your piece to which you would like to direct the class's attention? |

| Composer: | No. |

| Teacher: | Are you satisfied with your piece? |

| Composer: | No, not completely. |

| Teacher: | What is it that you are not satisfied with? |

| Composer: | Well, two things. I'm not satisfied with the layering process and I'm not satisfied with the ending. The ending does not allow the piece to sound as complete as I would like for it to. |

| Teacher: | Class, would you like to suggest any additional changes or modifications to the composer? |

(Silence)

| Teacher: | No suggestions. O.K., composer why don't you make your changes and bring your piece back next week and let us hear it again. Thank you. |

| Teacher: | Well, our time is almost up. Do you have any questions before we leave? |

| Student: | Does a piece have to have some kind of structure or shape? |

| Teacher: | I'm not sure if it has to, but I think anything you make will have some kind of form, even if it turns out to be just a one-part organization. |

| Student: | Well, if it will turn out to have some kind of form or shape or organization in any case, then why should we be concerned about creating structure or shape? |

| Teacher: | You don't necessarily have to be concerned about it. The point of questions of this type is to help you to develop the ability to exercise intelligent control over your materials. I'm concerned about whether or not you know what you were doing when you put your piece together. Remember, a musical composition comes into being as a result of sonic qualitative thought. And the more intelligent control you have over your materials, the more successful you'll be in creating musical compositions. |

(End of Period)

| Student: | I understand and accept what has been said so far, but it seems that the most important aspect of music is being ignored. |

| Teacher: | What is that? |

| Student: | Feeling—emotion. What counts is how I feel about a song, or how a song makes me feel. |

| Teacher: | Sure, I think that is generally true. |

| Student: | Yes, but we seem to be treating music like a science or craft rather than an art. When we bring feeling into the picture then we'll really get down to what you call the essence of music. |

| Teacher: | Let's pursue that. If we are trying to understand music, its role(s) in our lives, its effects, and affects, we certainly have to give feeling ample consideration. Why does music cause you to feel anything at all? |

| Student: | Because of the rhythms and pleasing sounds. |

| Teacher: | Why do you find sounds pleasing? What is it about the rhythms? |

(Silence)

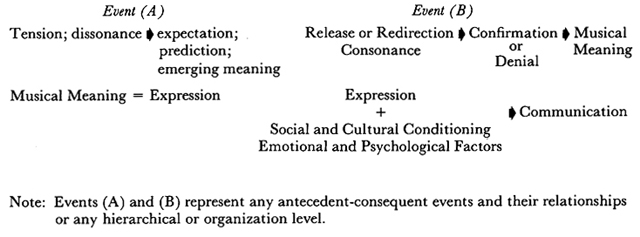

| Teacher: | Now we are in the realm of theory—musical aesthetics. There is no truth here. But let me offer this model for your consideration. For me, it explains the entire musical experience. I'll explain it now. Please study it at home and we'll discuss it next time. |

| While studying this model, please keep in mind the fact that dissonance-consonance relationships exist in all music, not just that which is "goal directed" or western-syntactical. |

MODEL FOR UNDERSTANDING THE MUSICAL EXPERIENCE

NEAR THE END OF THE TERM

| Teacher: | It's nearing the end of the term, and it's time we gave some attention to your final exercises. You have four options: |

| A. | You may compose a summary composition, a composition that will bring together most of those processes which we have been exploring during the past several weeks. | |

| Instructions: compose a piece summarizing all previous assignments made during the term. You should strive to make this piece your major, most ambitious project of the term, giving much attention to all compositional procedures and details. You should be especially concerned about: 1) the selection and utilization of timbres, 2) the composition, use, and effective connection of musical ideas, 3) shaping or structuring your piece effectively, 4) adequate and effective development of musical ideas, 5) careful selection of compositional means (see "9" below), 6) time, timbre, and loudness controls, 7) unity and variety, 8) employment of both homophonic and polyphonic textures, 9) employment of either serial or indeterminate procedure. | ||

| B. | You may take a listening examination that summarizes the events and processes to which we have devoted our attention during the past few weeks. The following questions indicate the nature of the exam: |

| 1. | This piece was probably composed or realized by means of: |

| a. | improvisation | d. | electronic procedures | |||

| b. | indeterminacy | e. | traditional procedures | |||

| c. | serial procedures |

| 2. | The pitch or structural organization of this piece may best be described as: |

| a. | traditional tonal | d. | atonal, but not serial | |||

| b. | modern tonal | e. | not having pitch controls | |||

| c. | atonal, serial |

| 3. | This piece may best be described as primarily: |

| a. | monophonic | d. | b and c above | |||

| b. | polyphonic | e. | none of the above | |||

| c. | homophonic |

| 4. | The basic time organization of this piece may be described as: |

| a. | either duple or triple meter | |||

| b. | mixed meter | |||

| c. | durational controls |

| 5. | The pitch structure of the main musical idea(s) is (are): |

| a. | largely conjunct | |||

| b. | largely disjunct | |||

| c. | rather mixed conjunct and disjunct movement | |||

| d. | none of the above |

| 6. | In this piece the various instruments are used primarily for their: |

| a. | contrasting qualities | |||

| b. | blending qualities | |||

| c. | both a and b above | |||

| d. | this question does not apply to this piece |

| 7. | What elements of music are most exploited by the composer? |

| a. | harmony | d. | loudness | |||

| b. | tone-color | e. | melody | |||

| c. | rhythm |

| 8. | This musical example relies on which kind of musical idea(s) as its subject matter: |

| a. | tune or theme | c. | rhythm motive | |||

| b. | pitch motive | d. | a and b of the above |

| 9. | Of the two main ideas employed, which is subjected to the most modification or development? |

| a. | the first | |||

| b. | the second | |||

| c. | This question does not apply: only one idea is employed |

| 10. | The rhythmic activity is highest at the passage: |

| a. | wherever the first idea appears in its entirety | |||

| b. | wherever the second idea appears in its entirety | |||

| c. | where the connecting passage which links the two ideas appears |

| 11. | The texture is thickest or about the same at the: |

| a. | beginning | c. | about the same in both | |||

| b. | end |

| 12. | The texture is thinnest at the: |

| a. | first idea | c. | about the same at both | |||

| b. | second idea |

| 13. | The greatest variety of tone-color in this piece occurs at the passage: |

| a. | where the first musical idea is initially presented | |||

| b. | where the second idea is initially presented | |||

| c. | where the connecting passage links the two ideas | |||

| d. | where the piece ends |

| 14. | Which term below describes the structure, shape, or process of this piece: |

| a. | AB | d. | "energy" shape | |||

| b. | ABA | e. | fugal | |||

| c. | theme and variations |

| 15. | What element or elements of music most affect(s) the structure or shape of this piece: |

| a. | tone-color | c. | loudness and timbre | |||

| b. | loudness | d. | rhythm, harmony, and melody |

| C. | You may write an essay (critical review) of two musical compositions. The essay will include a description of the works, your experience with the works, and critical evaluations of them. | |

| D. | You may carry out a project of your own choosing (with my approval) that is comparable to the first three options. |

This approach certainly will not be successful in every situation. Obviously, since there are no "lessons" in the traditional sense, it requires a resourceful teacher with experimental inclinations, as well as relaxed, curious, inquiring, inventive students. The two ingredients together, though, will create unforgettable musical experiences.