Six years ago, when the U.S.A. was only 196 years old, SYMPOSIUM (1972, Vol. 12, pp. 94-102) took a quizzical but unashamed look at the angled thickets of "Star-Spangled Bibliography," suggesting the national anthem in all its aspects as a topic ripe for interdisciplinary study—more attention to interdisciplinary studies having been called for by several writers in the previous volume. Pointing out various features of the anthem and its history that invite the attention of everyone from poet to meteorologist, we remarked that even "the music library cannot be neglected. Where did the tune come from—John Stafford Smith, or one who is nameless in history?" In closing, after discussing two then-recent books on the anthem, we observed that "unless some long-hidden proof as to the origin of the tune is henceforth discovered or adduced, the Svejda and Filby-Howard books are likely to represent for some time to come an end to historical studies of 'The Star-Spangled Banner.'"

That was that, until the Bicentennial Year finally turned from future into fact. No interdisciplinary study of the anthem having materialized, and no long-hidden source having come to light, the author decided to do his Bicentennial bit by trying his own hand at finding proof of the origin of the tune (an interdisciplinary study being beyond his sights) and also at putting forward some thoughts on the disconcertingly moot views held by many persons on the subject of "The Star-Spangled Banner." Some traveling, much digging into sources familiar and unfamiliar, and—Laus Deo!—a bit of luck combined to provide the following historical account, which is based upon an article that appeared in the July 1977 Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress. The author thanks the editors of the Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress for their cooperation in making this account available to many musicians who do not ordinarily see the Journal.

But why, some may ask, all this scholarly pother about the national anthem and its tune? Isn't it a fact that the anthem was born in battle during the British attack on Baltimore in September 1814?1 Doesn't everybody know that the tune comes from "an old English drinking song"? What about the complaints one hears today that "The Star-Spangled Banner" is both unsingable and unsuitable? Perhaps the most lurid of these complaints was voiced in a 14-page article that began:

Our national anthem is about as patriotic as "The Stein Song," as singable as Die Walküre, and as American as "God Save the Queen." . . .

Not only is "The Star-Spangled Banner" unsingable and unpeaceable, but it's un-American as well. Back in the 1700s a bunch of rakes and roués belonging to the Anacreontic Society of London decided they needed a song to accompany their shameless carryings-on at the Crown and Anchor Tavern. Two members, Ralph Tomlinson and John Stafford Smith, got together and quickly came up with something called "To Anacreon in Heav'n," a ditty dedicated to the grand Dirty Old Man of Greek poetry. Each verse of the lyrics—just to give you an idea of what it was all about—closed with the couplet,

And, besides, I'll instruct ye, like me, to intwine

The Myrtle of Venus with Bacchus's Vine.2

What is the truth about the Anacreontic Society and its song? "Did that society," as a member of a congressional subcommittee once asked, "do anything but drink, according to this folklore?"3 Was its song really a drinking song, or was it something even worse? And did John Stafford Smith, whoever he was, in fact compose the music, as nearly everyone in recent decades has assumed? What facts lie beneath "this folklore"?

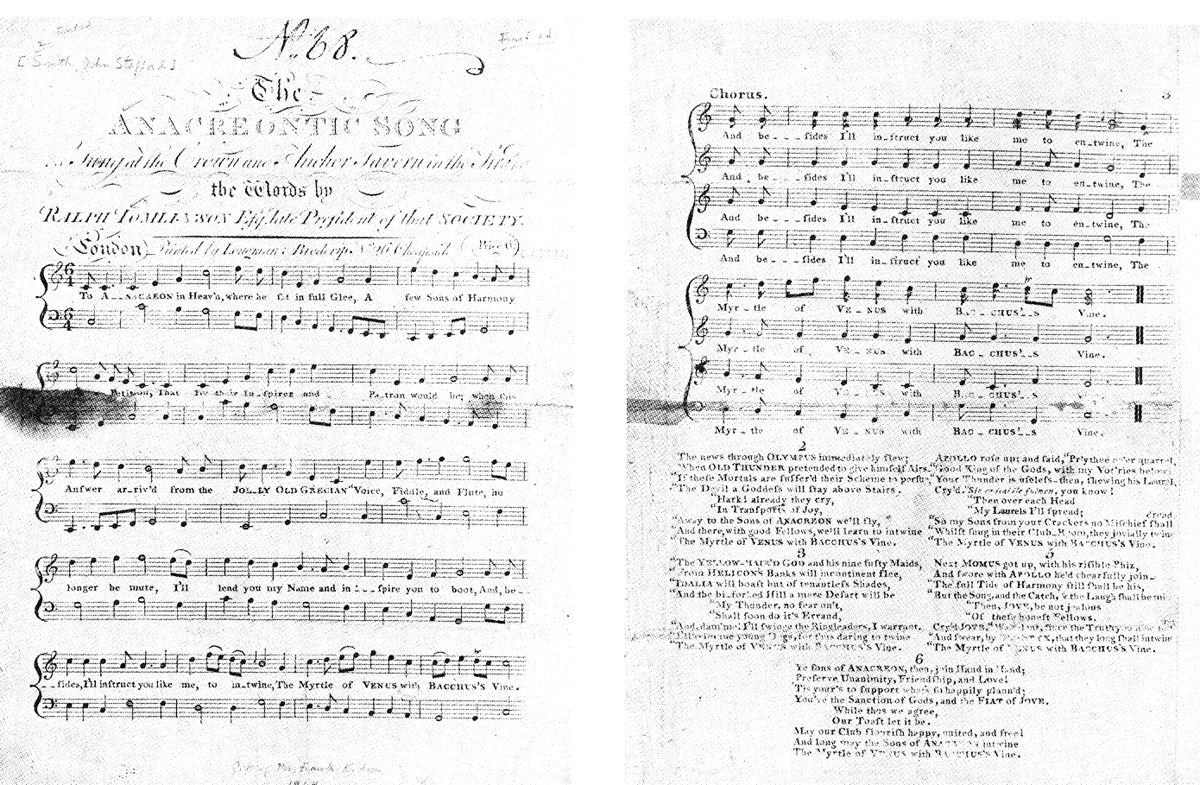

From the first sheet-music edition of "The Anacreontic Song," pub. ca. 1777-1781. (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

From the first sheet-music edition of "The Anacreontic Song," pub. ca. 1777-1781. (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

THE ANACREONTIC SOCIETY

Anacreon was indeed a Greek poet, born about 572 B.C. in the Ionian town of Teos. According to tradition, he died at the age of 85, perhaps in Athens, where he lived after 522 at the court of Hipparchus. His relatively small cache of surviving verse is usually characterized by such adjectives as urbane, witty, and ironic, and to a considerable extent it does celebrate the twin joys of love and wine—Venus and Bacchus.

But he was not the festive drunkard or amorous dotard of tradition. This reputation is due to the multitude of Hellenistic and Byzantine imitators, whose "Anacreontea" overemphasized the erotic and bibulous element, and substituted sugary, though sometimes charming, frivolity for the graceful freshness of the original. The earlier Anacreon exercised some influence on Horace; it was the pseudo-Anacreontic verse which was largely responsible for the poet's popularity in European literature, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.4

In England, this post-Restoration popularity of "Anacreontics," as they were called, coincided with the rise of an even more pervasive cultural phenomenon, the gentlemen's club. The reader can easily cite his own examples: Boodle's, the Kit Kats, the Sublime Society of Beef-Steaks, the Royal Society Club. Over the course of a century and a half there were quite literally hundreds of clubs, each centered around food, literature, science, music, or some other facet of gentlemanly living.5 The best known of the musical clubs was the Noblemen and Gentlemen's Catch Club, initiated in 1761; and surely the best known of all was The Club, later known as The Literary Club, formed by Samuel Johnson and Joshua Reynolds in 1764. Shortly afterwards came that "bunch of rakes and roués" known as the Anacreontic Society:

It was begot and christened by a Mr. S—th (1) about the year 1766, at a genteel public-house near the Mansion-house, was nursed at the Feathers and Half-moon Taverns in Cheapside, and received a great part of its establishment at the London Coffee-house (2).

The society at this house consisted of 25 members, and each member admitted his friend. Applications for admittance at this time became so numerous, it was thought necessary to remove the society to a house where the accommodations were more spacious. It was therefore carried to the Crown and Anchor in the Strand (3), and the number of members increased to 40, with the former indulgence of admitting friends. The year following, ten new members were admitted, and friends introduced the alternate nights only. About two years since (4) the number of members were increased to fourscore (5), and each member admits a visitor as before. The subscription at present is three guineas, and to a new member three and a half. The expense to non-subscribers is six shillings. The society opens generally about the middle of November, and their entertainments are on every other Wednesday till the twelve nights are accomplished. The concert, which consists of the best performers (who are honorary members) in London begins at half past seven, and ends at a quarter before ten. The company then adjourn to another room where an elegant supper is provided; in the mean time, the grand room is prepared for their return. The tables at the upper end of the room are elevated for the vocal performers. Here conviviality reigns in every shape, catches and glees in their proper stile, single songs from the first performers, imitations by gentlemen, much beyond any stage exhibition, salt-box solos, and miniature puppet-shews; in short, every thing that mirth can suggest.

The following, classical song, written by poor Ralph Tomlinson, their late president, is chorused by the whole company, and opens the mirth of the evening.

(1) Mr. S—th, better known amongst his acquaintance by the familiar appellation of Jack S—th, is a Dog at a Catch, and a corner-stone of Society.

(2) Mr. Bellas, President.

(3) Mr. Tomlinson, President.

(4) Mr. Mulso, President.

(5) The present members consist of Peers, Commoners, Aldermen, Gentlemen, Proctors, Actors, and Polite Tradesmen.6

Then followed the text under the heading "Anacreontic Song."

Although shorter, later, and less precise as a source of information on the society, Charles Morris's The Festival of Anacreon . . . nevertheless provides some additional items of interest:

In the infant state of this admirable institution, the members met as they now do, once a fortnight, during the winter season, at the London Coffee-house, on Ludgate-hill, who were chiefly of the sprightly class of citizens; but the popularity of the club soon increased the number of its members, and it was found expedient to remove the meeting to a place where the members could be more commodiously accommodated; the Crown and Anchor in the Strand was accordingly fixed on, where this meeting has ever since been held.

ANACREON, the renown'd convivial Bard of ancient Greece, as distinguished for the delicacy of his wit, as he is for the easy, elegant, and natural turn of his poesy, is the character from which this society derives its title, and who has been happily celebrated in the Constitutional Song, . . . universally acknowledged to be a very classical, poetic, and well-adapted composition; and if our information does not mislead us, it was written by a gentleman of the Temple, now dead, whose name was Tomlinson, and originally sung by Mr. Webster, and afterwards by Charles Bannister . . . ; for to do justice to the song, a very animated execution is requisite: that power of voice, happy discrimination, and vivacity, which seems peculiar to the well-known exertions of Mr. Bannister in this composition, never fail of producing him what he justly merits—unbounded applause.

Mr. Hankey, the Banker, a gentleman highly spoken of, as a man of polished manners and most liberal sentiments, now presides at this meeting, by whose management, in conjunction with the other directors, every thing is conducted under the influence of the strictest propriety and decorum.

The Concert, which commences at eight o'clock, and concludes at ten, is entirely composed of professional men in the first class of genius, science, and execution, which the present musical age can boast of. After the concert is over, the company adjourns to a spacious adjacent apartment, partake of a cold collation, and then return to the concert-room, where the remainder of the evening is totally devoted to wit, harmony, and the God of wine.7

In April 1783 an unnamed correspondent—possibly English but more likely of German or some other nationality—provided the earliest known description of the Anacreontic Society to foreign readers:

Some weeks ago I was invited to a concert in this neighborhood . . . About ten o'clock we went into another room for supper. While we were there the concert hall took on another shape: tables and benches were set out, and the platform formerly occupied by the orchestra was now taken over by singers, and the tables were provided with punch, shrub ["Bischoff"], and wine. That was the way we found things after supper, and it was not unpleasant to sit with a glass of punch and listen to good singing without instruments. They sang mostly canons, and very well. The singers who likewise sat behind the tables on the platform and were mostly amateurs, joined in with the punch, and the President announced the toasts. I hope to furnish you a detailed report on this organization that I trust will not be unwelcome.8

The picture that so far emerges of the Anacreontic Society meetings—tripartite in form, convivial but "of the strictest propriety and decorum," devoted to music both instrumental and vocal and to suitable food and drink as well—continues to hold as other sources are consulted. Oscar Sonneck, in preparing his 1914 report, a watershed in "Star-Spangled Banner" literature, apparently did not ferret out contemporary newspaper reviews or accounts of the meetings.9 The Times of London, now available in a run complete from the paper's origin in January 1785 as the Daily Universal Register, published approximately fourteen notices on the activities of the Anacreontic Society through 1795. The following account, written in 1787, is believed to be the earliest the Times printed:

ANACREONTIC SOCIETY. Wednesday the Annual Meeting of this truly convivial and respectable Society, was celebrated at the Crown and Anchor Tavern. The new room, which was opened upon this occasion, was at once elegant, brilliant, and convenient. Above two hundred members sat down to an excellent dinner, which was served up in a capital stile.

In the absence of Mr. Hankey, Mr. Williamson took the Chair—Mr. Bannister's illness preventing him from appearing in public, the Anacreontic Song was given by Mr. Sedgwick in a very pleasing and masterly style. . . .

. . . at ten o'clock on Wednesday night, the majority of the company departed, highly pleased with their entertainment.10

The absence of any reference to the initial concert and the unusually early hour of departure (by "the majority") suggest that each season may well have begun with an annual business meeting at which the concert was omitted. The allusion to "members" only, rather than to "members and visitors," strengthens the force of this suggestion; though certainly it would be wrong to deduce too much from a single instance.

Of the other notices of the Anacreontic meetings for the 1787-88 season, especially noteworthy is one in which the writer comments on the entire concert program, a program gargantuan by today's standards. Put in tabular form, it consisted of:

Two Haydn symphonies ("from the last set dedicated to his Royal Highness the Duke of York"—i.e., nos. 85, 86, and 87, published in London though not elsewhere with this dedication and generally known today as the last three of the six "Paris" symphonies).

Between these two symphonies, a piano trio from the pen of Johann Baptist Cramer, not quite seventeen years old, who played piano, with his father Wilhelm Cramer (who led the Anacreontic Society's orchestra from his position as first violinist) on violin and "Mr. Smith" on violoncello.

A violin concerto, composer unnamed, the solo played by Mr. Cramer Senior.

A duet on the horns by the two Leanders.

A duet for violin and violoncello by one Boaghi, played by Messers. Cramer and Smith.

Linley's "elegant little ballad of Primroses deck," sung by Charles Dignum accompanied by the orchestra ("but we think it would have been more pleasing . . . with the voice alone").

". . . and the concert concluded with a remarkably grand symphony," composer unidentified.11

Perhaps all the evidence is not yet in, but one might venture to suggest that the rakes and roués of today have not the staying power of their Georgian forefathers. Fortunately for all concerned, supper was then served in the adjoining room; but it turned out to be the chief target of criticism in the Times review:

Upwards of two hundred sat down to supper—the musical amateurs had been highly feasted; but those who preferred substantials to sweet airs were much disappointed.

A view of a large room, with elegantly decorated walls, is not sufficient to a hungry appetite. It is therefore recommended to Mr. Hope, to pay some little attention in future to the mouths of his guests; their ears are well-feasted, and there is but what we now suggest wanting on his part to render the entertainments of the evening highly finished. Things did not go off with glee after supper, which may be fairly attributed to the unworthiness of that entertainment, if it may be so called.12

The Times reporter (anonymous, in those times) was clearly among those who preferred "substantials to sweet airs"; and he clearly used the term musical amateurs in its original sense of "lovers of music."

Over the years exceptions to the society's usual patterns did occur. Perhaps because Easter was unusually early in 1788—March 23—the season's normal schedule of twelve to fourteen meetings began and ended over a month earlier than the customary November-May period, and the ordinary sequence of concert hall-supper room-concert hall was for once altered:

The meeting on Wednesday evening, the last for this season, was the most numerous and convivial one during the winter. . . .

The company retired to the Great Room to supper and a stage was erected for the vocal performers at the upper end.

The great inconvenience which the members and visitors had experienced on former occasions were removed by their continuing in the same room to finish the evening's entertainment.

As soon as the tables were cleared, "Non nobus Domini," was sung with great effect; the Anacreontic Song, by Mr. Sedgwick, followed. . . .

The whole was conducted with such order and regularity, as reflects the highest credit on the President and Managers of the society.13

The Anacreontic Society meetings of the next season were reported only twice in the Times, and those of the 1789-90 season not at all. Very likely there were three entirely separate reasons for this hiatus. The first is made clear in a report published on November 21, 1788: "The State of his Majesty's health . . . had its strong effect. Conviviality lost its usual power; and the meeting broke up at an early hour. . . . The supper room was but thinly attended. The feast was more for the mind than the body. . . ."

King George III had suffered his first major attack of what was then referred to in terms ranging all the way from indisposition to madness. But after some months he seemingly recovered, and it is hard to believe so popular and well-established a group would have been permanently stricken by His Majesty's misfortune. One has only to turn the pages of the Times in that period to see that precious space was reserved almost daily for reports on the sovereign's condition. A similar shortage of news space resulted the following year after the Bastille was stormed, for events in France claimed a major share of the Times's columns. Then in the spring and summer months of 1790 the Crown and Anchor was torn down and rebuilt, providing more commodious quarters not only for the Anacreontic Society but for other organizations that met there.14

By the autumn of 1790, the Crown and Anchor was back in business and the Anacreontic Society returned to its place in an occasional Friday issue of the Times. A report on what must have been one of the high points in the musical life of the society follows:

The meeting of last Wednesday evening was not only the fullest, but the most convivial that has been this season. The company seemed to be in full glee, and determined to be merry.

Mr. HAYDN, from Vienna, was introduced to the meeting, for the first time, and received by Mr. Hankey, the President, with great civility. On entering the Concert room he was greatly applauded, and the band very opportunely played one of his charming concertos [symphonies]. Perhaps Mr. Haydn never heard his compositions done so much justice to.

Young HUMMEL, from Vienna, a boy about twelve years of age, astonished the company with a most admirable performance of a favourite English ballet, with variations, on the harpsichord. Perhaps there never was a stronger instance of youthful genius and musical skill.

The Anacreontic song was sung by Mr. Incledon, who likewise favoured the company with two other airs, and in a manner that delighted them to a degree of enthusiasm. Mr. Incledon may be proud of the unanimous applause which succeeded them. Catches and glees made up the rest of this charming entertainment.15

Perhaps one may hazard a guess that the Times never printed a more "charming" music review!

As with many human endeavors, disaster seems to have befallen the society through an excess of success. The earliest hint of trouble appears in the London Gazetteer, which contains a notice of the "Haydn concert" that took place on January 12, 1791:

The Society met on Wednesday, at the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand, and was very numerously attended.

The concert, led by Cramer, was a selection from the best masters, and executed with wonderful effect. Before the grand finale the celebrated Haydn entered the room, and was welcomed by the Sons of Harmony with every mark of respect and attention. The band played one of his best overtures [symphonies], with the performance of which he expressed himself highly gratified; after which he retired amid the plaudits of the whole assembly.

In the course of the evening Parke gave a solo on the hautboy, and the younger Cramer and Master Hummel exhibited their surprising abilities on the Piano-Forte.

A small party of ladies occupied the gallery that overlooks the Concert-Room seemingly so pleased with the instrumental performance, that they returned after supper, joining chorus with "Anacreon in Heaven," and his convivial votaries, till "Sigh no more, Ladies," gently whispered the restraint which modesty ever imposes on the midnight crew.

Neither Dignum nor Sedgwick were there—but Incledon, Bernard, Mess. Cooke, Hooke, &c. &c, contributed all in their power to make up the deficiency, and the meeting did not break up till near two o'clock yesterday morning.16

C.F. Pohl's book Mozart and Haydn in London sets the stage for Haydn's visit to London by giving short accounts of the various London musical organizations, among them the Anacreontic Society. Although Pohl does not identify any of his sources of information, he not only mentions the presence of ladies but provides the earliest reference seen to a certain amount of prolonged carousing:

This musical society in the nineties held all fourteen of its meetings, beginning in December, in the ballroom of the Crown and Anchor in the Strand. The committee is made up mostly of merchants and bankers. Besides vocal works, the society also performs symphonies and quartets. Here Dr. Arnold was again the conductor (in 1785 he had dedicated to the society a select collection of Anacreontic songs). The concerts began around seven o'clock in the evening. After the performance of a symphony by Kozeluch, Pleyel, Le Duc, Mozart, or Haydn, in which Cramer functioned as leader, there would follow a quartet by Pleyel or Haydn played by Cramer, Mountain, Black, and Smith, and some solo pieces. Then the company made its way to supper in an adjoining hall, where some 180 to 200 persons took their places at three tables.

After the meal, the Anacreontic Song ("To Anacreon in Heaven") would be sung by Charles Bannister, Dignum, or Incledon. Then would follow some solo songs and a varied series of lively catches and glees, sung by Webbe, Danby, Dignum, Hobbs, Sedgwick, Suett [Knyvett?], Incledon. The last-named is in particular often mentioned as singing "The Banks of the Tweed." During the supper they were certain to admit some ladies, who could look out from the orchestra gallery and watch the high jinks—which, as it appears, they found very much to their liking, so that it was a nuisance to be reminded that the time had come to withdraw when "the power of the wine began to overcome the gentleness of the myrtle." So far as the masculine part of the company was concerned, however, Dr. Arnold knew how to hold their attention so that for most of them it was close to three o'clock in the morning before they remembered hearth and home; indeed, "they blushed not if on occasion the sun itself lighted them on their way home from their revels [Schwelgereien]."17

Ladies in the gallery at the Anacreontic Society? Less than three weeks after Haydn's visit, the Times reports: "The ANACREONTIC MEETING of last Monday evening was by far the fullest of this season, as well as the most convivial we have witnessed for some years. . . . The Ladies through the lattices of the Orchestra looked like a seraglio of Turkish beauties." Farther down in the same column, not a part of the review itself, a startling complaint catches the eye: "The ladies stay too long after supper at the ANACREONTIC—not contented with the delicacies of the musical FEAST, they seem anxious, by way of bonne bouche, to taste a slice or two of the convivial GREEN FAT!"18

A seraglio of Turkish beauties? Lattices? Green fat? Fortunately we do not have to guess at what was going on, for William T. Parke, the well-known oboist who played at the society regularly beginning in 1786, tells us in his memoirs:

This society, to become members of which noblemen and gentlemen would wait a year for a vacancy, was by an act of gallantry brought to a premature dissolution. The Duchess of Devonshire, the great leader of the haut ton, having heard the Anacreontic highly extolled, expressed a particular wish to some of its members to be permitted to be privately present to hear the concert, &c.; which being made known to the directors, they caused the elevated orchestra occupied by the musicians at balls to be fitted up, with a lattice affixed to the front of it, for the accommodation of her grace and party; so that they could see, without being seen; but, some of the comic songs not being exactly calculated for the entertainment of ladies, the singers were restrained; which displeasing many of the members, they resigned one after another; and a general meeting being called, the society was dissolved.19

One major and newfound source of information about the Anacreontic Society yields further clues regarding its closing; but since it is important first of all in connection with the tune of "The Anacreontic Song," we shall at this point postpone consideration of it. Before the tune, let us more briefly deal with the text, so often maligned but so little known.

RALPH TOMLINSON AND "TO ANACREON IN HEAVEN"

There never has been any serious doubt as to where the text of the song originated.20 It was printed some thirty times in Britain before 1800, in songsters (collections of song texts alone), sheet music, and song collections with tunes. Nearly all of these printings attribute the words to "Ralph Tomlinson, Esq." So do the first two sources on the Anacreontic Society quoted above, using the expressions "poor Ralph Tomlinson" and "a gentleman of the Temple, now dead, whose name was Tomlinson." The only questions were: Who was Tomlinson and what became of him? The two expressions quoted above were not taken at face value because "Tomlinson, Ralph, attorney, 13 Chancery Lane" is to be found from the 1770s through 1797 in Browne's General Law-List, the annual directory of the English legal profession of the time. Various obituary indexes and many other guides proved unavailing.

It turns out that for decades Browne had misled everyone, carrying Tomlinson as a "ghost" in his pages over a period of nineteen years. The Middlesex Court record of the administration of Tomlinson's estate reads as follows:

RALPH TOMLINSON On the twentieth Day Administration of the Goods Chattels and Credits of Ralph Tomlinson, late of Gray's Inn in the County of Middlesex Batchelor deceased was granted to John Philpot a Creditor of this said deceased having been first, sworn duly to Administer, Ann Tomlinson widow the natural and lawful Mother and next of kin, Charles Tomlinson and John Tomlinson the natural and lawful Brothers, Ann Reece (Wife of Thomas Reece) and Esther Tomlinson Spinster the natural and lawful Sisters of the said deceased having first respectively renounced the Letters of Administration of the Goods of the said deceased.21

To end the search happily and successfully, Ralph Tomlinson's death date of March 7, 1778, and burial date of March 11 were located.22

Tomlinson's baptismal date of August 17, 1744, had already been discovered in the parish register of Plemstall Church, beautifully set in the Cheshire countryside four miles northeast of Chester.23 Ralph was apparently the eldest child of Randle or Raendel and Ann Tomlinson. Two younger sons were Charles, a beer brewer and a warden of Plemstall Church, and John, who became a surgeon. Both were made Freemen of the City of Chester.24 Ralph's name is not found on the rosters of graduates of Oxford or Cambridge Universities.25 He may have read law somewhere else or as an apprentice in a law office. He was admitted in 1766 to the Society of Gentlemen Practisers in the Courts of Law and Equity, and in 1769 to the Society of Lincoln's Inn.26 But there is no evidence that he was ever called to the bar, so he would have remained what later became known as a "solicitor."27

Poor Ralph Tomlinson, indeed. Despite his apparent success as president of the Anacreontic Society, despite his having created a song poem that itself is still alive after two centuries, he has been nothing but a name in history.28 He must have been struck down rather suddenly by some accident or disease. According to the court record of the administration of his estate, he died not only a bachelor at the age of thirty-three but—attorney though he was—intestate as well; so with the agreement of his family, a creditor was named his executor. Apart from his contributions to the Anacreontic Society, only one other accomplishment of his has been uncovered: "A Slang Pastoral: Being a Parody on a Celebrated Poem of Dr. Byron's. Written by Ralph Tomlinson, Esq. London: Printed for the Editor, MDCCLXXX." This epitome of the parody form in its commonest and narrowest sense is a slightly coarse but hardly bawdy takeoff on John Byrom's Colin and Phoebe, itself an epitome of the dainty nymphs-and-shepherds brand of pastoral poetry. It must have been tossed off for some unidentified occasion or publication.29

And what of the Anacreontic poem itself? It certainly is not great poetry, but neither is it a "dirty ditty." For a song of its kind and place it shows a genuine imagination, a touch of whimsy to accompany its pseudo-classical setting. Oscar Sonneck comments: "Though his poetry is not of a high order Tomlinson 'intwined the myrtle of Venus with Bacchus's vine' with very much more fetching inspiration and spirit than many other poets of fugitive convivial poems of typically eighteenth century Anacreontic atmosphere which I have read."30 The adjectives applied to the song in the various sources on the society quoted above show that the "constitutional song" was regarded with respect and even admiration by members and nonmembers alike. The "intwining" that Mr. Braun pounces on obviously has to be taken metaphorically; there is no evidence that Venus and Bacchus ever intwined on the premises, so to speak.

The earliest known printing of Tomlinson's text in any form is represented without music in the Vocal Magazine, or British Songster's Miscellany, dated by its frontispiece August 1, 1778.31 For a long time this was the only known printing of the original version, but in 1976 the same version—with exactly the same heading and no doubt copied from the Vocal Magazine—was discovered in a curious collection called the Festival of Momus.32

The various editions of the Vocal Magazine and the Festival of Momus present bibliographical complexities that are unimportant here. The significant point about both collections in all their editions with regard to "The Anacreontic Song" is that two lines show this to be Tomlinson's original version of the text, written before the move from Ludgate Hill to the Strand, which led to revisions removing allusions to the original meeting place. For example, in stanza 2, line 7, of the original version, "A fig for Parnassus! to Rowley's we'll fly" is modified in the revised version to "Away to the Sons of Anacreon we'll fly." Stanza 3, line 2, of the original version, "To the hill of old Lud will incontinent flee," became in the revised version: "From Helicon's Banks will incontinent flee." Rowley was a wine, cheese, and snuff merchant who did business on the same premises as the London Coffee House.33

But Ralph Tomlinson and his poem are not an integral part of our national anthem, merely a phase of its prehistory. What is most relevant here is where the tune came from and where it is going. Did Tomlinson write his words to a preexisting tune as did Francis Scott Key? Or did someone actually sit down and think up this so-called unsingable melody, which has in fact flourished now for two centuries? Until now there have been four stages of opinion in this matter.

THE ANACREONTIC TUNE

Stage one extends for some sixty-five years from the beginning of the song, during which time there was complete silence in print—with one debatable exception—as to the origin of the tune. There are no credits for the music on the sheet-music editions, though sheet-music publishers usually show more concern for the composer than for the author of the words.34 There are no known attributions in such printed sources as diaries, memoirs, newspapers, or advertisements, though for decades, even long past the birth of "The Star-Spangled Banner," there must have been people alive who knew where the tune originated. Francis Broderip, the junior partner of Longman and Broderip, publishers of the first sheet-music edition and two later ones, was a member of the Anacreontic Society.35 He must have known the source of the tune, and he probably was the one responsible for the first publication of the song. Why was there no composer's name on it?

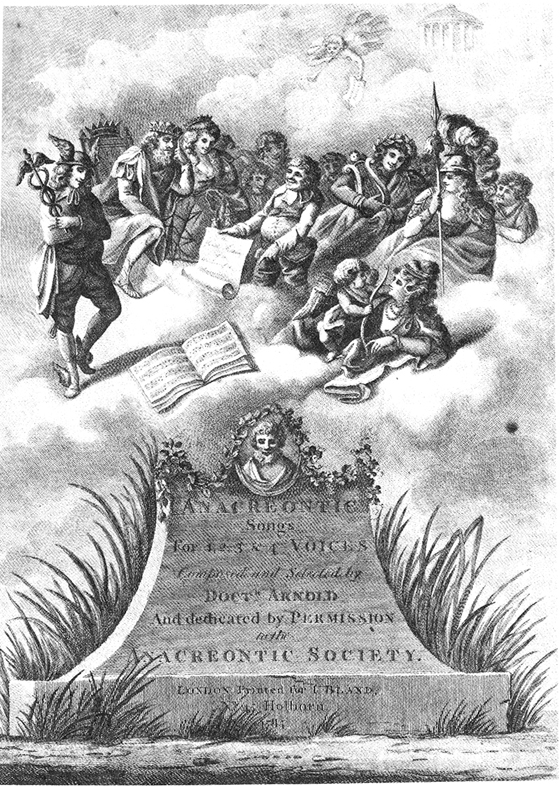

The second stage began allegedly in 1841, when it is said that someone using the initials "J.C." wrote in the Baltimore Clipper that the composer was Samuel Arnold (1740-1802).36 Arnold had conducted off and on at the Anacreontic Society and was its last president. It was a good guess, as guesses go, especially since there was another reason to suspect Arnold of being the composer—a reason that J.C. probably was not aware of: in 1785, J. Bland of London published a handsome folio volume of Anacreontic Songs for 1, 2, 3 & 4 Voices Composed and Selected by Doctr. Arnold and Dedicated by Permission to the Anacreontic Society.37 Its pictorial title page shows a scene obviously drawn from Ralph Tomlinson's Anacreontic poem.

On the pictorial page of Samuel Arnold's Anacreontic Songs, engraved by Sparrow from the design of Robert Dighton, Momus is showing Jove, or "Old Thunder," the "humble petition of the members of the Anacreontic"; Apollo, at Jove's right, is ready to support the petition; and Anacreon, presumably the figure behind Momus with the lyre and laurel wreath, is busy winning the affections of a goddess. (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

On the pictorial page of Samuel Arnold's Anacreontic Songs, engraved by Sparrow from the design of Robert Dighton, Momus is showing Jove, or "Old Thunder," the "humble petition of the members of the Anacreontic"; Apollo, at Jove's right, is ready to support the petition; and Anacreon, presumably the figure behind Momus with the lyre and laurel wreath, is busy winning the affections of a goddess. (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

In these circumstances, one would expect "The Anacreontic Song" to be first in the volume; instead, it is nowhere to be found in it. Sonneck, noting that the Library of Congress copy shows irregular pagination with no index and that it was obviously printed from plates of existing sheet-music editions, wondered if this copy happened to lack "To Anacreon in Heaven" through some error. He was able to check this copy only against the copy in the then British Museum, which shows the same irregularities. The author, however, has examined these two copies as well as the five other copies known to him and has found that they all agree in their irregularities. Sonneck discusses other possible reasons for the omission, though he overlooks the fact that Longman and Broderip had already published the song and may have been able legally to prevent a rival edition. Nevertheless, Sonneck seems perfectly correct in concluding that "if Arnold had composed 'To Anacreon in Heaven' he presumably would have inserted it in the collection."38 So much for stage two.

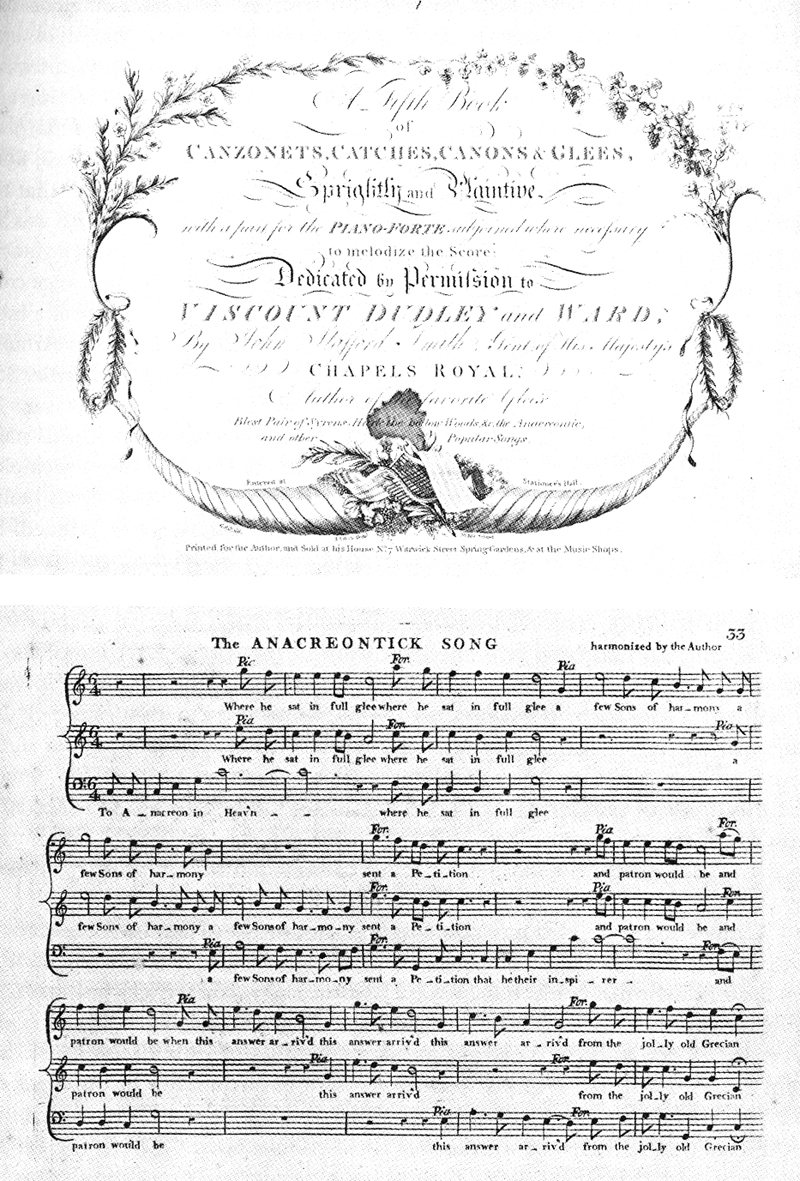

The third stage began in either 1799 or 1873, according to one's viewpoint. On October 21, 1872, Stephen Salisbury, then president of the American Antiquarian Society, read a paper before that society in which he referred to Arnold as the composer of the tune of "The Star-Spangled Banner" (J.C.'s claim having been picked up by others and copied even into the present century). Salisbury's paper was published separately and in at least three different journals and in some way came to the attention of the well-known London music merchant and scholar William Chappell. In a communication to Salisbury and in a letter to Notes and Queries, Chappell wrote, in effect, "Don't be silly: the composer was not Arnold but John Stafford Smith. True, his name does not appear on the sheet music editions, but the song is in Smith's Fifth Book of Canzonets, Canons, Catches and Glees, where at page 33 it is found 'harmonized by the Author.'"39 Reproductions of the title page and page 33 from this collection appear in this article, and the reader may judge Chappell's argument for himself.

Title page from Smith's Fifth Book of Canzonets, and the first page of his three-part glee arrangement of "The Anacreontic Song." (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

Title page from Smith's Fifth Book of Canzonets, and the first page of his three-part glee arrangement of "The Anacreontic Song." (Courtesy, Library of Congress)

Chappell based his claim for Smith on the belief that when Smith said "harmonized (that is, arranged for three voices from the solo song) by the author" he was using "author" in its sense of "original composer of the tune" rather than in its other possible meaning here of "author (compiler) of this collection." The title page was another matter: Chappell misread it near the bottom to claim Smith as "Author of the favorite Glees . . . 'Hark the hollow Woods,' and of 'The Anacreontic' and other Popular Songs." This tiresome matter of a few letters, spaces, punctuation marks, and a capital letter played its part in stage four. Had Chappell's reading actually appeared on the title page it clearly would have proclaimed Smith as the composer of "The Anacreontic and other Popular Songs." But that is not the way the title page reads. When one knows that Smith was the composer of a glee called simply "Anacreontic" that has nothing to do with "The Anacreontic Song," one sees that Chappell had carelessly removed the existing ambiguity of the title page.

Chappell's claim was taken up by others, though Arnold's name is still occasionally found even after World War I and W.H. Grattan Flood and John Henry Blake were busy promoting their own bizarre claims. All of these theories were conscientiously sifted and studied by Sonneck in his centennial report, and all of them save one were dismissed. Considering all the claims and counter-claims and all the evidence he could glean from Smith's Fifth Book, including the fact that searches at Stationers' Hall had disclosed May 8, 1799, as the copyright date, Sonneck finally stated his "personal opinion" that the Fifth Book indeed constituted sufficient proof that John Stafford Smith was the original author of the tune.40 One reads between the lines that Sonneck glanced wistfully back over his shoulder at Samuel Arnold, who as a noted stage composer rather than a church-and-glee composer like Smith would seem a more likely possibility. But the absence of "The Anacreontic Song" from Arnold's collection of Anacreontic songs was a seemingly insurmountable hurdle. Sonneck saw no one else in sight as an acceptable possibility, so Smith it was.

Sonneck's verdict, based on so thorough an investigation with his name and that of the Library of Congress behind it, carried the day. Library catalogers, publishers, and virtually everyone who had to attribute the tune to someone or else leave the space for a composer's name blank were convinced. Everyone, that is, except at the Library of Congress, where catalogers carefully retained Sonneck's properly cautious question mark following Smith's name as composer, and where Richard S. Hill (1901-1961) was in a quandary. In 1940, when Hill had been reference librarian in the Music Division of the Library for less than a year, he was asked by the division chief Harold Spivacke to prepare a four-page pamphlet on the national anthem that could be sent out to the numerous inquirers who, with World War II approaching our shores, were showing increased interest in the anthem and its history. Two decades and hundreds of typescript pages later, Hill had solved to his satisfaction almost all of the many problems relating to the history of "The Star-Spangled Banner" itself. But he remained at an impasse when it came to the source of the tune.

Unlike Sonneck, Hill had come to believe that John Stafford Smith could not possibly have been the composer of the Anacreontic tune. He did not understand how Smith could have lived for some sixty years after composing the tune, for twenty-two years after the birth of "The Star-Spangled Banner," and never once been known to say or have someone say for him "That music is by John Stafford Smith." As for the alleged claim of authorship in the Fifth Book of 1799, Hill interpreted author as "author of this collection." It was pointed out to him that in 1799 the word author most often tended to mean the original creator of something, whether a book, a poem, a picture, or a tune. It was likewise explained that Smith's copyright claim at Stationers' Hall was as "author" of the "whole," and that no one had ever claimed any of the other musical works in Smith's five volumes for anyone other than Smith. Hill could reply that Smith was indeed the creator of something—he was the creator of the entire Fifth Book as a published volume. He could also counter that the third of Smith's five collections contains a three-part canon on "God Save the King," the tune of which Smith certainly did not compose. He could further counter that Smith's copyright claim on the "whole" of the Fifth Book had to be as compiler only; he did not, so far as we know, write any of the texts he set to music.41

As for the use of author on the title page of the Fifth Book, Hill had an ingenious explanation. He pointed out that the first glee mentioned, "Blest Pair of Syrens," is in Smith's first published collection; the second, "Hark the hollow Woods, &c." (with "&c." being substituted for "Resounding," to accommodate the spacing of the line), is found in Smith's second published collection; in the third collection there is a glee with the one-word title "Anacreontic"; and the fourth book does not have the word glee in its title—though there are glees in it—but rather "Songs," thus conforming to the wording of the sales bait.42 This was an explanation that fit the characters that Chappell had misread and that Sonneck probably assumed to be the result of careless printing.

Sonneck considered but rejected the possibility that Tomlinson had done just what Francis Scott Key did: made up his text to fit an extant tune. He corresponded about this possibility with Frank Kidson, the "authoritative and industrious collector of British folk and popular airs." Kidson wrote that in all of his investigations he had never "run across any melody in British collections, printed or manuscript, that could by any stretch of imagination be identified with the air of 'To Anacreon in Heaven.'" Sonneck modestly seconded that finding on the basis of his own searches and experience and concluded "that single melodic snatches, phrases, motives, or half motives of 'To Anacreon in Heaven' are common enough in musical literature . . . but in its entirety as melody 'To Anacreon in Heaven' appears to have had no prototype."43

Hill, on the other hand, came to believe just the opposite. He did not accept the alleged claim of the Fifth Book, nor did he believe that any composer alive could have failed to identify himself at some point with a tune that became so popular in Britain and America, latterly in a way completely unforeseen. Not finding any evidence for Arnold or anyone else in the picture, Hill concluded by elimination that Tomlinson must have put his words to a melody that already existed. Because of the tune's considerable dependence on the tonic triad—which, for example, supplies fourteen out of the first seventeen notes in the modern "Star-Spangled Banner" version—Hill wondered whether the tune had not come from military music, where trumpets and horns at that time were still limited by the lack of valves and pistons to the natural overtone series in which they do not achieve all the tones of the diatonic scale until they reach up almost to the height of "the rocket's red glare." With much help in Britain and America, Hill searched a large part of the pre-1775 tune repertory; but, as with Kidson and Sonneck, no prototype was found. Hill was tantalized by a bandsman's book in the Sutro Library of San Francisco that contains the Anacreontic tune captioned "Royal Inniskilling." He could show that the book had once belonged to a musician in the band of the Sixth Enniskillen Dragoons (the Irish and the colloquial English spellings are different). An Irish correspondent swore that his mother always said that the "'Royal Inniskilling' was mother to 'The Star-Spangled Banner.'" But Hill could find no evidence of the tune's existence under this title before 1799. He was too sound a scholar to publish without conclusive evidence, and during that impasse he tragically died. Thus ended stage four.

AN OLD TALE WITH A NEW TWIST

In 1914 Oscar Sonneck wrote:

One may indeed express surprise that John Stafford Smith waited until 1799 before he publicly claimed the music of "To Anacreon in Heaven" as his own. But are we really certain that he did not claim it years before? May there not be hidden away somewhere in "the wreck of time" . . . direct evidence of Smith's authorship, if not his own manuscript, then perhaps some reference in contemporary letters or the like?44

By a sad irony of fate, not long after Hill's death in 1961 his good friend, the late Charles Cudworth, librarian of the Pendlebury Music Library at Cambridge University, acquired just such a reference, one lone sentence buried in ten volumes of manuscript "Recollections" and "Diaries" written by Richard John Samuel Stevens (1757-1837). For a century and a quarter these manuscript volumes had remained in the possession of Stevens's descendants. One of those descendants, the late J.B. Trend, professor of Spanish at Cambridge University, had them in his possession in 1932 when he published an article based on one of Stevens's occasional biographical sketches of his contemporaries.45 Apparently Professor Trend was not aware of the importance of this particular sentence, if indeed his eye ever happened to fall on it.

Stevens has usually been regarded as one of the lesser figures in English music of the late Georgian period, itself generally and somewhat unfairly viewed as a dismal hiatus between the death of Handel in 1759 and the appearance in 1829 of another foreigner on the English scene—Felix Mendelssohn.46 Stevens was born on March 27, 1757, just inside the wall of London City, directly across from Bedlam. He was apprenticed to William Savage, a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal with the duties of organist at St. Paul's Cathedral, where Stevens sang in the choir until his voice broke in 1773. His apprenticeship ended on December 15, 1775, and for the next two and a half years he earned what money he could by various engagements, either as tenor vocalist or at the keyboard, until in June 1778 he secured a moderately decent position as organist at St. Bride's Church, Fleet Street. In 1781 Stevens "won the duty" at St. Michael's Cornhill, and from then on his career prospered: teacher at Dulwich College and elsewhere, organist for the Inner Temple from 1786 to 1810, organist at the Charterhouse from 1796, Music Master to Christ Hospital from 1808, and from 1801 until his death on September 23, 1837, Gresham Professor of Music.47

Although Stevens published keyboard sonatas and a few sacred works, he was known primarily as a glee composer. In particular, he is said to have been one of those who, in the latter days of this uniquely English musical form, played a part in transforming the glee from a combination of equally melodic parts into the part song, in which one voice has the melody and the others merely provide harmonic adornment.48 These facets of Stevens's own career, however, are not as important to our purpose as the fact that in his "Recollections" he shows a clear concern for accuracy and fairness in his remarks about others. He was not without humor or a gently barbed—sometimes blunt—pen, but in writing his "Recollections" he made every effort to not only appear but actually be proper, fair, sober, and conscientious.

By a quirk of fate, it is one of Stevens's rare "indiscretions" that leads him to mention the Anacreontic Society. In the period between his apprenticeship and his position as deputy to Dr. Howard at St. Bride's, Stevens needed every shilling he could earn, and some of his engagements took him far from home and kept him out long after midnight. The result was that his early morning keyboard practice suffered along with his health. Under the general date of 1777 and following an account of how he failed to win a church job on May 4, he mentioned his late engagements and their dissipating effect on him: "I regularly attend the Anacreontic Society: this was another of my late engagements; as I was willing to see and hear all the fun and frisk of these convivial assemblies." This sentence leads Stevens into a tale of how his father, concerned about his health, tried to get him to give up music and go as a super-cargo on a ship carrying woolen goods to the British in the warring colonies. The ship, as it turned out, was captured by the French. Fortunately, Stevens's confidence in himself had prevailed; he had remained in London. He returns in his "Recollections" to the Anacreontic Society, still writing (in 1808) under the general heading of 1777:

As I have mentioned the Anacreontic Society, it may not be improper to give some account of that Popular meeting. It was first held at the London Coffee House, on Ludgate Hill, but the room being found too small, it was removed to the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand, then kept by one Holloway. The President was Ralph Tomlinson Esqre, very much of a Gentleman, and a sensible, sedate, quiet man: I believe that he was a Solicitor in Chancery. He wrote the Poetry of the Anacreontic Song; which Stafford Smith set to Music: this Song was sung by Webster, when I first attended the Society. The President, and I believe, a Committee of Eleven Gentlemen, had the intire Management of the Funds of the Society. The Evenings entertainment began at seven O Clock, with a Concert, chiefly of instrumental Music; it was not very uncommon to have some Vocal Music interspersed with the Instrumental. Mr. Sabattier was the Manager of this department, and generally stood behind the Person who was at the Piano Forte. At ten O Clock the Instrumental Concert ended, when we retired to the Supper rooms. After Supper, having sung "Non nobis Domine" we returned to the Concert Room, which in the mean time had been differently arranged. The President, then took his seat in the center of the elevated table, at the upper end of the room, supported on each side, by the various Vocal performers. After the Anacreontic Song had been sung, in the Chorus of the last verse of which, all the Members, Visitors, and Performers, joined, "hand in hand," we were entertained by the performance of various celebrated Catches, Glees, Songs, Duettos, and other Vocal, with some Rhetorical compositions, till twelve O Clock. The President having left the Chair, after that time, the proceedings were very disgraceful to the Society; as the greatest levity, and vulgar obscenity, generally prevailed. Improper Songs, and other vicious compositions were performed without any shame whatever. I never staid till the Society broke up, which was generally very late. When Mr Tomlinson died, he was succeeded by Mr Richard Hankey, who conducted the Society with great spirit, had gentlemanly manners, and was an admirable Chairman. I think he resigned his Chair after being President ten or twelve years. The next President was Mr James Curtis; a convivial man; frothy, vain, and silly. Next followed Mr Edward Mulso (rather in years) Profound, and Grave. And when the Society was upon its last legs, Doctor Arnold, (silly enough) would be President to oblige Simpkin, now the Landlord. There was neither consequence, ability, or understanding enough in the Doctor, to conduct such a popular Musical Society. Shortly after this time, the Anacreontic expired very quietly. At this Concert, I have frequently heard Clementi, and Dance, on the Harpsichord: and Shroeter, on the Piano Forte. I remember Cardon, a french man, playing upon the Harp here, in a most surprising, and masterly manner: I have never heard such Harp music since. Cramer, Barthelemon, and Pieltain, I have heard on the Violin: Paxton, and Cervetto, on the Violoncello: Parke, Patria and Le Brun, on the Oboe. All the eminent Instrumental Musicians that arrived from the Continent, used to make their debut at the Anacreontic Society, in order to give a specimen of their abilities. But the Vocal phalanx after Supper was very considerable; both from the number, and from the Character and Professional eminence of many of those of whom it consisted. Some times, we had Dr Cooke, Webbe, Paxton, Knyvet, Hindle, Harrison, Linley, Danby, Stevens, Percy, Webster, Jack Smith, Stafford Smith, Vernon, and Reinhold. (Latterly, Edwin, Bannister, Sedgwick, Dignum, and Huttley.) Bartleman, (a boy), C. Knyvet Junr, (a boy), S. Webbe Junior, (a boy). Beside these Vocal Performers, there were Mr Pain, and Mr Tom Hawes, names now almost forgotten, who were much Celebrated for their exact imitation of the Actors and Actresses. . . .49

Portrait of John Stafford Smith, about age seventy, from the frontispiece of The Apollo or Harmonist in Miniature, vol. 2 (London, 1822). The engraving, by T. Illman, is from the original drawing by W. Behnes.

Portrait of John Stafford Smith, about age seventy, from the frontispiece of The Apollo or Harmonist in Miniature, vol. 2 (London, 1822). The engraving, by T. Illman, is from the original drawing by W. Behnes.

(Courtesy, Library of Congress)

JOHN STAFFORD SMITH

We have seen, at last, a matter-of-fact and unequivocal statement that it was indeed Stafford Smith who set Ralph Tomlinson's poetry to music, a statement by someone who participated in music-making at the society when Ralph Tomlinson was president and "The Anacreontic Song" was in its early years. True, Stevens wrote the statement some thirty years after his chief period of attendance at the "popular meeting" and his memory was not infallible about all details, especially ones before or after his main attendance, such as the original meeting place or the order in which the presidents served. But his entire "Recollections"—which cover the period 1757-1827, thus running concurrently with the "Diaries," which record the years 1802-37—show a remarkable degree of accuracy concerning matters of which he had personal knowledge. He must have kept programs, letters, pay chits, clippings, and probably informal memoranda, in addition to possessing an excellent memory for episodes and anecdotes. One of the latter testifies that Stevens and Smith were well acquainted, no doubt from having performed often together at the Anacreontic Society and elsewhere and from belonging to the same circle of London church musicians centered around the Chapel Royal, St. Paul's, and the Westminster Abbey. In May 1782 Stevens finally won a gold medal in the Catch Club competition for the best "serious" glee. Invited to the dinner at which the medals were awarded, Stevens saw Smith across the room and started to go over to greet him. Smith turned his back, saying, "I shan't speak to you, you have cheated me out of a Gold Medal."50

As for the phrase "set to music," it was perhaps then more commonly used than today in place of "composed," and it does not imply that Smith took the words and set them to already-existing music. (When any composer reaches into his subconscious for music suited to his immediate purpose, it is seldom possible for him to say how much of what emerges has been influenced by music heard and perhaps forgotten by his conscious mind.) William Chappell, in his communication to Notes and Queries summarized above, used exactly the same phrase to indicate that Smith was the composer of the Anacreontic tune.51

Be it granted, then, that John Stafford Smith was the composer of the Anacreontic tune and, hence, of "The Star-Spangled Banner." It is difficult to believe that Stevens may have erred either intentionally or unintentionally, and the evidence of "author" on page 33 of the Fifth Book now seems a bit more convincing. Certainly the tune was a sport in more ways than one, coming as it did from a man whose whole career was closely associated primarily with the Church of England and secondarily with the catch-and-glee milieu.

John Stafford Smith, the son of Martin and Agrilla Stafford Smith, was baptized at Gloucester Cathedral on March 30, 1750. Stafford received his first musical training from his father, who was organist of Gloucester Cathedral from 1740 to 1782, and his first musical experience as a choirboy in the cathedral choir.52 When Stafford was quite young he was sent to London to study organ and composition with William Boyce, a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal who knew Martin Smith from the Three Choirs Festival when it was held at Gloucester, and whose daughter, Elizabeth, Smith later married.53 In 1761 young Stafford became a chorister under James Nares, the Master of the Children at the Chapel Royal. He continued to sing there as an adult, was deputized as an organist and no doubt in other capacities, and on December 18, 1784, was made a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal. Shortly thereafter, Smith was appointed lay-vicar at Westminster Abbey where, upon completion of his probationary year, he was installed on April 18, 1786. In 1802 he became one of the two organists at the Chapel Royal, and on May 14, 1805, was made Master of the Children. He retired from his post in June 1817, but continued to live on Paradise Row in Chelsea, dying there on September 21, 1836.

From early manhood Stafford Smith composed a great deal of secular as well as sacred music.54 He also took an interest in music of earlier times, an interest that was unusual for his day. In his early twenties he aided Sir John Hawkins in the preparation of his General History of the Science and Practice of Music (5 vols., London, 1776) by lending him and transcribing for him early manuscripts "from his extensive and curious library."55 In 1779 Smith published through John Bland of London A Collection of English Songs . . . Composed about the Year 1500 . . . , one of the songs being the now famous "Agincourt Song." In 1812 at London T. Preston published Smith's Musica Antiqua, a Selection of Music of This and Other Countries from the Commencement of the Twelfth to the Beginning of the Eighteenth Century. Smith was, in fact, one of the earliest "musicologists"—though he probably would have disliked the word even as most of his countrymen do today.56 Perhaps there is some connection, remote though it may be, between Smith's interest in music of an earlier day and the Anacreontic tune. The latter undoubtedly belongs to its early homophonic period; yet, after looking at hundreds of other tunes of that time and of the preceding generation, one cannot help noticing how different this one is, not only in range but in contour and spirit. It shows little in common with the glees, catches, canons, and other occasional songs for which Smith was known in the nineteenth century. It may be that in an effort to match the pseudo-classical whimsy of Tomlinson's poem Smith's mind reached back into music of an earlier period for a suitable inspiration. In any event, he achieved a melody that is surely sui generis.

Smith lived toward the end of a period when fashions in music were changing. He wrote largely in forms that were primarily English and that did not travel well abroad. In 1914, the very centennial year of "The Star-Spangled Banner" in which Oscar Sonneck almost officially declared Smith as the composer of its tune, one Harry Colin Miller published a series of lectures in which he remarked: "The name of John Stafford Smith is now little remembered except perhaps as the auther of a few glees and one or two anthems and chants. There is little doubt that in his day he occupied a high place in his profession as organist, composer, and writer on music."57 William A. Barrett was kinder to Smith when he wrote the following evaluation of his work in 1886:

. . . he produced a number of works of rare beauty, the emanations of a mind of no common order.

The greatest efforts of his genius were made in the composition of his glees. He gained two prizes in 1773 for a catch and a canon, and in the four following years he was a successful competitor for the distinctions given by the Catch Club.

Unlike most prize glees, his are admirable, and . . . any earnest praise of them . . . can scarcely be said to be extravagant or ill applied.

. . . The ruthless march of fashion has left nearly all his sacred compositions behind and unregarded. . . . He shone with somewhat of a borrowed light in the region of sacred art. His genious was pre-eminently happier in secular composition. . . .58

Barrett evidently did not know what William Chappell knew and therefore could not guess how sound a judgment he had made. It is worth noting here that "The Anacreontic Song" probably was written in 1775 or 1776, during the period of Smith's run of prize medals at the Catch Club.

What of Smith the man, as opposed to the churchman and composer? The story has been told by Sir John Goss, a prize pupil of Smith's at the Chapel Royal, of how Smith one day met Goss with a copy of Handel's organ concertos under his arm. Smith reminded Goss that he was there to learn to sing, not to play. Thereupon Smith seized the volume, whacked Goss on the head with it, and took it away with him, "though," says Goss, "I had bought it out of my hardly-saved pocket money, and I never saw it again."59 Yet Barrett writes that "Smith was particularly fond of this boy." He took him with him on walks and told him about his own experiences as a Chapel lad and of the great men with whom he had come in contact. In particular, he held out Handel, whom he had seen and remembered, and Thomas Arne and Joseph Haydn, both of whom he had known, as models for imitation when Goss would write:

He regretted even then the growing fashion for discarding the pure principles of melody in favor of massive startling harmonies and the fascinations of instrumental colouring. "Remember, my child," he was wont to say, "that melody is the one power of music which all men can delight in. If you wish to make those for whom you write love you, if you wish to make what you write amiable, turn your heart to melody, your thoughts will follow the inclination of your heart.60

Revealing in a very different way are the hundreds of observations, copybook maxims, quotations from Pope and Dryden and many unidentified writers, remarks about rival composers, rules of grammar, and philosophical profundities—all scribbled in Smith's own hand in several manuscript volumes. The British Library possesses one volume, and a few sheets from much later in his life than any of the others are at the Royal Society of Musicians of Great Britain.61 The treasure beyond compare, however, is the so-called commonplace book in the Euing Collection at the University of Glasgow Library. This small, oblong volume of 130 leaves was originally the recipe book of Smith's paternal grandfather.62 About half of the pages, which are written in an awkward hand and archaic script, contain recipes for everything from ink to a cure for a venereal disease. In the ample margins around the recipes and on the many empty pages, over the period 1763-88, Stafford Smith scribbled a variety of reflections, maxims, quotations, and letter drafts. Here are a few samples:

1784. Jan 17th carried the Canon "Honi soit qui mal y pense" to Warren—who reproach'd me on ye difficulty of [correct?] Marriage: Many know Tom Fool yt Tom Fool does not know. Call'd me artful; Twas time to be artful when Rogues pretended to Honesty—He did not relish left-handed compliments.

Raggamuffin¦¦Scaramouch¦¦Battishill¦¦Willet [folio 120v].Integrity tho' banished by all the rest of ye world, ought to be found in ye words & actions of Kings [folio 124v].

Mr. J.S.S. presents his compliments to Mr. W. Horner & assures him without equivocation that ye little encouragment he has experienced will in future prevent him from being catch'd in a Club again. On ye 23d he is pre-engaged [folio 118r].63

Paxton, Webbe and Danby's writings, combine the common place passages of modern Organists with ye stiffness of ye Mass Music [folio 118v].

. . . Ye Italians have always endeavored to tickle ye ear not to inform ye Judgement. Jones has not ye knowledge of ye Grounds of Harmony which books wd give him / Arnold & Dupuis just enough to put parts together in a bungling manner [folio 127r].

Frivolous music is neither decent nor elegant—no, nor does it contain true spirit [folio 125v].

Had I been a Knave of Hearts or a Fool of Diamonds, a Club wd have knockt me down, & a Knave of spades wd have buried me– –in a Woman's Arms [folio128r].

That which excites surprise much sooner cloys than yt which soothes, the mind.

Namby-Pamby Musick, are Catches & Glees of slight texture. short Airs; Gavots & Variations.

The disgust wch blank verse, encumbering and encumbered, superadds to an unpleasing subject, like ill-mannered vulgarity in a tradesman, soon repels a mind of sensibility however willing to be pleased.

Brevity & compression gives vigour to Composition.

Wynnstay Septr 25th 1774.

From the above place Sir W.W. Wynne sent me "Now [if?] bright Morning" & "Blest pair of Syrens," to set [folio 76r].

The Mind naturally loves truth. The permission of evil in ye World & the doubts & Difficulties in which it involves us, cannot be more satisfactorily accounted for, than by supposing it intended as a probationary trial to prepare us for a better life [folio 68v].

Manuscript add. 34,608 in the Manuscripts Department of the British Library has more in a similar vein, for example: "Sigh no more Ladies &c by Stevens is Recitative, magnetical Key, more measured less energetic, more airy, less passionate yn ye common," and "to speak Music—language must bend metre and Rhythms and music must not snarl or Crawl out ye numbers" (folio 24v).

Commonplace books tend to be less organized than diaries and perhaps are even more private to the writer. It seems that Smith judged his fellow musicians with great severity—perhaps he judged himself the same way, though one wonders—and that his conscious mind was full of concern for probity and high moral purpose in music as well as in daily life. Perhaps this characteristic explains Smith's apparent failure to associate his name in print with "The Anacreontic Song," excluding page 33 of the Fifth Book. Did he feel that its frivolous purpose was at odds with his desired public image of a serious church musician working his way up through the hierarchy of the Chapel Royal and the Abbey? But surely the song is not as frivolous in nature as many of the catches and glees for which he was known.

Perhaps Smith composed the song for Tomlinson for money, for a flat fee, which meant yielding his legal rights in it to Tomlinson or the Society. That seems to be the most reasonable explanation for the absence of his name on the official Longman and Broderip editions, from which the others no doubt were pirated, along with Tomlinson's name as author. We know from Stevens that Smith was one of the "vocal phalanx" at the society in the period when the song must have been created, somewhere in the period 1775-76. Smith was only in his middle twenties and he must have married not long before he applied for membership in the Society for the Support of Decayed Musicians and Their Families, for as a young bachelor he would have had little concern for the society's protection. He won Catch Club prizes in 1773, 1774, 1775, 1776, and 1777. What could be more natural than that Tomlinson should turn to this up-and-coming honorary member of the society and offer him an "honorarium" for putting the aptly whimsical poem to suitable music?

A third possible factor in explaining Smith's puzzling lack of public association with the song is that in later years—and perhaps throughout his life—he seems to have scorned public acclaim. Smith had been retired from active duty many years before his death, and although data concerning his career were easily accessible, there was absolutely no interest on Smith's part to record the events of his life.64 In preparing his Dictionary of Musicians (London, 1824 and 1827), John Sainsbury solicited autobiographical information from most of the English musicians of the day, many of whom were much less prominent than Stafford Smith. Yet there is no evidence in the materials in the Euing Collection assembled by Sainsbury that Smith even answered Sainsbury's request. The very brief article published under Stafford Smith's name, probably thrown together by Sainsbury himself, does not mention "The Anacreontic Song." Finally, Smith's marginalia in his copy of Charles Burney's General History of Music (1776-1789) show his bitterness at the public acclaim Burney won at the expense of Hawkins's History, which Smith had helped to prepare. Where Burney had observed "It seems natural that the hope of applause and the fear of censure should operate powerfully on the industry of a composer," Smith had scribbled: "To gain meretricious praise? Pooh!"65 Was Smith so embittered by lack of appreciation of his music by his contemporaries or by failure to achieve some goal he had set for himself in life that he sincerely spurned public reference to his work? One can only guess.

It is more than a guess, however, to say that Smith was only an honorary member of the society, a performer who must have received a fee for his singing. Some of the top virtuosos may have appeared without pay, as the correspondent to Cramer's Magazin der Musik claims, if they wanted to enhance their positions or—when newly arrived from the Continent as Stevens relates—if they wanted to display and advertise their abilities to attract lucrative offers. But it is impossible to imagine such young musicians as Smith and Stevens, badly needing money, performing as honorary members without some money changing hands. Neither Sonneck nor Hill ever found the slightest evidence for the supposition that Smith was a subscribing member of the society, as various writers have assumed. Evidence to the contrary may be found in the following letter draft on folio 9v of the Glasgow commonplace book:

Mr. S.S. presents his best respects to Mr. Alderman Turner & the rest of the Members of the Anacreontic Society, and thanks them cordially for the unexpected honor of being elected one of their Society. But this year his business has led him into such engagements as will prevent his attending their Meetings. He therefore hopes for their pardon as he would by accepting the honor deprive another person of a pleasure which it is not in his power to enjoy himself.

There is, of course, no absolute assurance that the letter was actually sent and accepted, but in the complete absence of any hint anywhere that Smith ever was a regular member, there appears to be an overwhelming likelihood that it was. From the reference to Alderman Turner, who must have succeeded Edward Mulso upon Mulso's death in January 1782 and who was knighted in January 1784, one assumes the letter was drafted and sent sometime between those two dates. This theory is the most plausible, unless the invitation to Smith was signed by Turner as chairman of an admissions committee or something similar rather than as president, which seems unlikely from what is known of the society.

HUGGER-MUGGER AT THE SOCIETY?

What of the startling passage in Stevens's "Recollections" where he speaks of the period after midnight, when the president had left the chair: ". . . the greatest levity, and vulgar obscenity, generally prevailed. Improper Songs, and other vicious compositions were performed without any shame whatever." Has Mr. Braun scored at last? Stevens very primly says that he "never staid till the Society broke up, which was generally very late." But what of his earlier admission about enjoying "all the fun and frisk of these convivial assemblies"? Perhaps he is referring to the vocal frolics before midnight, when the president was still in the chair; perhaps his knowledge of the "vicious compositions" was purely hearsay. Yes, perhaps. At any rate, he makes it clear that for some of the members the meetings were not only tripartite but quadripartite.

What, one wonders, did Stevens consider "vicious compositions"? He must have been referring to the texts, for music by itself is neither moral nor immoral save by association. On page 128 of his "Recollections" Stevens had listed, as he did every year in this period, the prize-winning compositions in the Catch Club competition—the first Tuesday in May, he tells us, was always "Decision Day." He cites the prize-winning catch for 1785, J.W. Callcott's "A Beauteous Fair," and by it at some later time he has written the word Obscene. This catch illustrates nicely the vocal interchange and verbal interplay that characterize the catch form, one voice "catching up" another. A double entendre provided by one word in the middle voice makes the catch obscene for Stevens.

Years later, in the early nineties, Stevens sang regularly at what must have been the most patrician club of all, the Je Ne Sais Quoi Club, which numbered the sons of George III among its members, the Prince of Wales being permanent chairman. Stevens twitches his nose at the gluttony and drinking that went on there and remarks particularly on "the actors that attended this Club, to sing songs of every description many of which were very disgusting, disgraceful, and horrible to hear. . . ."66 Yet the vocal repertory at the Je Ne Sais Quoi Club, as at the Anacreontic Society, was no doubt based to a considerable degree on the publications of the Catch Club. There are very few words in the catches which, taken by themselves, would be considered vulgar; the bawdiness exists in the context and the double meanings.67 The present generation of Englishmen and Americans, however, would hardly turn a Hair at the club repertory. Perhaps at the Anacreontic meetings, as the early morning hours wore on and the wine bottles piled up in the scullery, some songs "too vicious to print" were passed from gentleman to gentleman in folk fashion. And perhaps it was this postmidnight activity that felt the dampening effect of the ladies "staying too long after dinner" as the Times put it, thus causing resignations and ultimate dissolution. One of the chief reasons for the rise of gentlemen's clubs, one senses, was that they provided the gentlemen a refuge to which they could escape from the ladies.

But that is beside the point. Enough reputable sources have been quoted to show that the Anacreontic Society was a highly regarded group devoted to good music and to good living in the terms of the day. Its reputation was high for both music and mirth. That any "convivial" society could sit through three symphonies, a concerto, a piano trio, and assorted lesser pieces before turning to food, drink, song, and "mirth" gives new meaning, I think, to conviviality. And "The Anacreontic Song" was the society's "constitutional song," sung with no doubt solemn and whimsical glee by the president or his deputy to open the after-supper portion of the meetings. Only the last two lines of the last stanza were chorused by all present, standing hand in hand to signify good fellowship. One can guess that after midnight, when the formal program was over, some groups of more venturesome lay members and their guests may have essayed the song at the tops of their voices (where it is much easier to sing, as many timid complainants today would learn if they dared). But the song was not intended for group singing or for amateur singing at all. It was not a barroom ballad, a drinking ditty to be chorused with glasses swung in rhythm. It is convivial, but in a special and stately way; and the text is simply a good-natured takeoff on a bit of pseudoclassical mythology.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE ANACREONTIC SOCIETY

circa 1766-93

Tucked between the pages of the first volume of Stevens's "Recollections," having remained miraculously in place through 140 years of various changes in ownership, is a slip of paper on which Stevens and James Curtis—named by Stevens as one of the presidents of the Anacreontic Society, albeit "frothy, vain, and silly"—made up a list of the society's presidents when they met one February day in 1823 on the London-Peckham coach. Though it is known that they did not remember the names in the proper sequence, the slip presumably does list all of the presidents of the society, except Samuel Arnold, whom they no doubt viewed as a rump president having no status. Tomlinson must have been so far to the front of their minds that they failed to put his name down until Stevens entered it later, in pencil. With all of the information Stevens provides plus that from other sources, some of which have been quoted or cited here, it is now possible to draw up a very rough and sometimes tentative chronology of the Anacreontic Society:

CIRCA 1766: Society is formed by Jack Smith and several like-minded devotees of music and mirth. Smith is mentioned among the vocal performers at the society when Stevens attended and may possibly be the "Jn. Smith, attorney, Chancery-1a" who died on October 8, 1780.68 The first meeting place was a "genteel public house" near the Lord Mayor's mansion.

1767-70/72: Jack Smith presumably still president. The society increases its membership gradually from a handful of friends to fifteen or perhaps twenty and moves westward along Cheapside by way of the Feathers and Half Moon Taverns to the London Coffee House on the north side of Ludgate and up against the west wall of St. Martin's within Ludgate, with Stationers' Hall just to the east at the rear in Amen Corner. Here the membership reaches twenty-five, and George Bellas, attorney, is president.69

JANUARY 15, 1776: "Yesterday died, at his house in Doctors' Commons, George Bellas, Esq."70