EDITOR'S NOTE: This is the second in a series of brief articles—which began in our last issue—requested from the Research Center for Musical Iconography (RCMI), International and American National Headquarters of Répertoire International d'Iconographie Musicale (RIdIM). An article describing the founding and objectives of the RCMI was published in this journal, Volume XIII (Fall, 1973), pp. 106-13.

The etching of a "Concert Ticket" and the drawing of "A Musical Company" reproduced here are not only fascinating musical and art-historical documents, but symbols of an important forward step in the work of the Research Center for Musical Iconography and its parent organization, Répertoire International d'Iconographie Musicale. The present study will explore the nature of these art works and their position in RCMI's recent exhibition, The Musical Ensemble ca. 1730-1830, as well as outlining the progress of the RIdIM/RCMI venture. A bit of background may be in order first.

Musical iconography—or iconology—is the study of the representation of musical subjects (performers, performing sites, instruments, singers, music scores, etc.) in the visual arts (painting, graphics, sculpture, etc.). Its vast ocean of sources constitutes a rich, largely untapped, body of evidence for the study of performance practice, social history (e.g., status of musicians, patronage), pictorial symbolism (mythological, biblical, and contemporary), musical and art-historical chronology (paintings have been precisely dated by musicologists familiar with the musical details depicted), etc. In the delineations of musical instruments, of players, singers, and all kinds of groups of performers of sacred and secular music, there is a wealth of information pertaining to playing methods; to the shape, construction, and function of instruments; to the grouping of performers—for instance, the proportion between vocal and instrumental bodies; to the sites of performances; etc. This evidence is often far superior to that found in contemporary verbal descriptions of performances and instruments. For obvious reasons, writers do not take the trouble to describe what is taken for granted in their time.

A graphic or pictorial rendering will often present its subject with a precision of detail and degree of accuracy not attainable through other sources. On the other hand, it should be remembered that the interpretation of pictorial representations of musical topics, like that of other subjects, is susceptible to many pitfalls such as artistic license, inept restoration, and the stylistic idiosyncrasies in any given period; these must be understood in order to arrive at valid conclusions about available visual evidence.1

Joining RISM and RILM, RIdIM was created as a third, major, international bibliographic undertaking to foster musicological research. It was founded in 1971 in St. Gall, Switzerland—under the joint auspices of the International Musicological Society, the International Association of Music Libraries, and the International Council of Museums—and its headquarters were established soon thereafter at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Prior to the founding of RIdIM, there was no internationally accepted method for systematically cataloguing and accumulating visual materials for musical-historical study. The international gathering and exchange of pictorial materials, together with the perfection of a multi-faceted cataloguing and indexing procedure, have aided in uncovering unknown sources and using them to gain insights into a variety of musicological and art-historical problems.

In assessing its progress to date, RIdIM/RCMI has:

1) developed an internationally agreed-upon means of cataloguing visual materials and outlined detailed instructions in many languages to facilitate its use.

2) created an ever-expanding research facility (RCMI) with thousands of musico-iconographical documents and reference tools, both published and unpublished, available to teachers, students, scholars, librarians, publishers, etc.

3) founded the RIdIM/RCMI Newsletter—containing brief papers, descriptions of iconographical collections, reports of conferences, listings of new publications, etc.—as a means for the communication and exchange of information in this field. Five issues have thus far appeared; subscriptions can be obtained at a modest rate from the RCMI office.

4) sponsored or co-sponsored many meetings at annual IAML sessions and quinquennial IMS congresses. In addition, six international conferences on musical iconography have taken place each spring since 1973 at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Many musicologists, art historians, sociologists, and literary historians from the United States and abroad have participated.

5) established a logical procedure, patterned after RISM and RILM, for the coordination of international accumulation. Series A/1 now encompasses European paintings from 1300 to the present. The A series will continue in future years with drawings (A/2), graphics (A/3), etc. Series B involves accumulation in specific areas under the supervision of individual scholars or small groups of scholars; topics include Greek vases (B/1), Wall Paintings of the Early Middle Ages (B/2), The Viol Family (B/3), Musical Inscriptions (B/4), Drums and Drummers (B/5), Caravaggistes (B/6), Portraits (B/7), The Meeting of Eastern and Western Influences in the European Instrumentarium (B/8), Eighteenth-Century Ensembles (B/9), Iconographical Sources in L'Illustration (B/10).

One of the Series B accumulation topics—Eighteenth-Century Ensembles (B/9)—served as the focal point for a recent exhibition and panel discussion titled The Musical Ensemble ca. 1730-1830, part of the Sixth International Conference on Musical Iconography, held at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York on 15 April 1978. The etching and drawing reproduced here are two of 243 art works—both original prints and photographic reproductions of paintings, sculpture, porcelain, prints, and other media—that were included in the show. The aims of the exhibition were two-fold: to test the international accumulation and exchange hypothesis upon which RIdIM is based and to elucidate the nature and variety of the questions involved in understanding the performance of eighteenth-century music.

The first objective, that of testing the accumulation potential of RIdIM, was met through the cooperation of a number of national RIdIM committees and individuals from throughout the world. Although a substantial number of reproductions were collected, they were presented as work-in-progress and represent a portion of the projected total. Only when the full weight of the evidence is in—and when that evidence is coordinated with other largely untapped sources of information, such as archives, unpublished memoirs, newspaper advertisements, etc.—will hypotheses be fully tested and conclusions convincingly drawn. A description of each of the works included in the exhibit, as well as an introductory essay describing the state of research on the project, is found in the catalogue of the exhibition (obtainable through the RCMI), a future revised and expanded version of which will incorporate the many new photographs that will have been received since the exhibition.

In working toward the second objective, that of gaining insight into questions of performance during this period, the exhibition served to bring many observations to light through the juxtaposition of such a large quantity of materials. The works included in the exhibit were organized systematically with the intent of promoting contrast and comparison. Twelve categories were devised: street, peasant, and tavern scenes; dance; the decorative arts; house music; ceiling frescoes, drawings, exotica; fêtes galantes and patio scenes; court, church, and city ceremonies; theater and concert hall; the salon; collegia and rehearsal scenes; outdoor music-making; and caricatures. Although the choice of groupings was occasionally dictated by the demands of the exhibition space, it was principally fashioned with the intent of providing a logical framework for the presentation of the material.

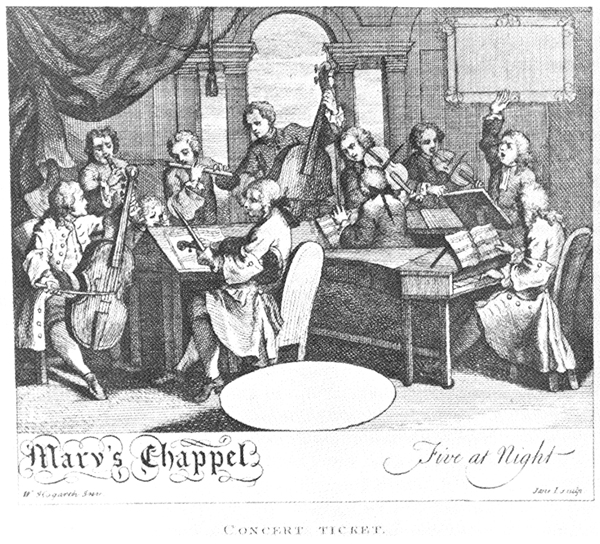

The etching "Mary's Chappel: Five at Night/CONCERT TICKET" and the drawing "A Musical Company," both from the "House Music" category, are illustrative of the rewards, and especially the pitfalls, that such a compilation can present. These two works raise various questions—both musical and art historical—and differ in their value as documents for the study of eighteenth-century performance patterns. The first work to be considered, "Mary's Chappel . . . Concert Ticket," presents problems on several levels: the question of its authenticity as a work of Hogarth; the identification of Jane I., who signed the plate; the dating of the print and of the image after which it was created; the naming of some of the instruments; the position of the work in the history of the musical concert ticket; and the reliability of the depiction as a realistic ensemble.

Figure 1. William Hogarth, del. (?); Jane I., sculp.

Mary's Chappel: Five at Night/CONCERT TICKET, etching.

New York; formerly in Wurlitzer-Bruck Collection,

presently in J.-J.-B. de Ruisseau Collection.

Although the etching of a "Concert Ticket" is signed "W: Hogarth Inv.," there is some question as to whether or not Hogarth was involved in its creation. The print was made in 1799, well after Hogarth's death in 1764, and there is no record of Hogarth's having created a design for the plate. Ronald Paulson, in his catalogue of Hogarth's graphics, does not refer to this print, but, under the category of "Prints After Hogarth's Design," describes another very similar etching created after the same image (probably a drawing).2

In opposition to earlier opinion, Paulson considers the drawing upon which this print is based to have come from the hand of Hogarth.3 Paulson is dealing with an etching produced by Gerard Vandergucht (1696-1776), who was employed as an engraver in Hogarth's studio. Our print, however, was not etched by Vandergucht, but rather bears the signature "Jane I. sculp." Although our etching is not included in Paulson's listing, it bears an almost exact resemblance to the image reproduced therein; what, therefore, is its origin?

The clue to tracing the etcher of this work is found at the bottom of the print where it states "Pub. for S. Ireland May 1, 1799" (not visible in the reproduction). Jane I.—the signer of the plate—was the daughter of Samuel Ireland, an eminent eighteenth-century collector of Hogarth's engravings, who prepared a two-volume study of his collection and whose collection now forms the substance of the Hogarth holdings at the Royal Library, Windsor Castle.4 In preparing his survey of Hogarth's engravings, Ireland and his daughters, Jane and Anna Maria, created the plates for the book. Our etching is a result of this enterprise.

This "Concert Ticket" is an interesting example of the freedom with which eighteenth-century printmakers copied the work of other artists and of the tendency for them often to base their engravings or etchings on a painting or drawing created many years earlier. It is therefore obvious that the date of 1799 affixed to this print is accurate insofar as it records the year in which the plate was made, yet it cannot be relied upon for dating the performance style depicted, because the drawing after which the work is patterned was created many years earlier (costumes and wigs suggest ca. 1730).

There are some problems in the identification of the instruments as well. Although the two violins, viola, and double bass—together with their players—seem reasonably well depicted, the other instruments are inaccurately rendered. On the left is seen a viola da gamba player holding his instrument in a conventional position; the instrument, however, has only four strings stretching from the five visible pegs (the presence of a sixth peg behind the hand of the performer is assumed). Behind him stands a man playing an instrument so severely foreshortened—or simply cut off—that it looks like a soda bottle. The grimacing member of this group, seated beneath the flute, plays a hidden instrument. Further problems are encountered with the backwards flute—either a left-handed senior piccolo or junior flute—and the harpsichord, which is also backwards, resulting in the placement of the treble strings on the left and the bass on the right. Although the image is often reversed in prints copied verbatim from drawings, this error—curiously—is inconsistent here.

Other questions yet to be answered include: What and where was Mary's Chappel? Was this a ticket for a regular concert series? (Since this is a passe-partout in which the event might have been written in the empty oval space at the bottom, it is possible that it could have been used for a series of concerts.) Was 5:00 P.M. a regular concert time? Although the gathering of more data will dispel some of these questions, many aspects of this etching provide inadmissible evidence. On the face of it, this is hardly a dependable historical document.

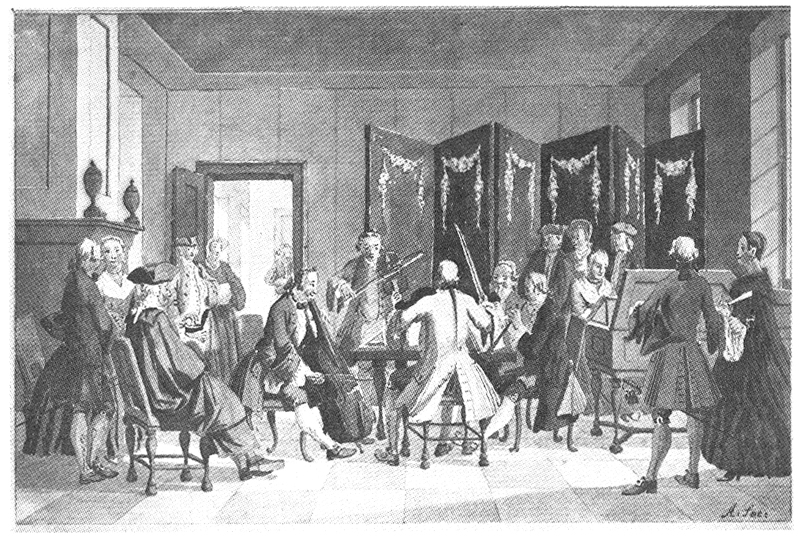

In turning to the drawing of "A Musical Company," we find a work that, although not created (presumably) by an artist of the stature of Hogarth, is much more trustworthy as a piece of musico-iconographical evidence.

Figure 2. Nicolas Aertmann.

A Musical Company, drawing. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum.

The drawing, signed "A:fec:," is listed by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam as coming from the hand of Nicolas Aertmann. Unfortunately nothing seems to be known about this man; he is not listed in any of the major art-historical dictionaries or in any of the well-known studies of this period.

The persons depicted are obviously engaged in informal music-making, probably in a private home. Seated at a keyboard instrument is the only woman instrumentalist—a common phenomenon in informal performances of this time, as was clearly demonstrated in the exhibition. The other performers are gathered around a table outfitted with music stands; the ensemble, in addition to the keyboard, consists of two violins, violoncello, oboe, and a probable oboe. One gets the impression of a quick sketch from life: the seating of the musicians is reasonable, their attitudes vis-à-vis their instruments is normal, the table-top music stand is quite common. The evidence depicted in this drawing is admissible in court. From it, and hundreds of similarly admissible bits of evidence, the valid conclusions we are seeking, about how music looked in performance in the eighteenth century, will be drawn.

In the near future the RCMI, in addition to its international-headquarters' obligation, plans to concentrate on: 1) an expansion of its study of eighteenth-century ensembles, 2) the pursuit of a specialized investigation of the viol family in conjunction with work on the viola da gamba, already well underway in Paris at the Centre d'Iconographie Musicale, 3) a study of what can be learned from Greek vase paintings, and 4) the accumulation of visual evidence of music and musical life in America. Perhaps the most important of RCMI's obligations is the inventorying of musico-iconographical holdings in American libraries, museums, and private collections. Anyone interested in collaborating in the inventorying process in his own city or area or in working in any of the specialized projects mentioned above should contact:

Research Center for Musical Iconography

City University of New York

Graduate School and University Center

33 West 42 Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

1Emanuel Winternitz, "The Iconology of Music—Potentials and Pitfalls," in Perspectives in Musicology, ed. Barry S. Brook, Edward Downes, and Sherman Van Solkema (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1972), 80-90.

2Ronald Paulson, Hogarth's Graphic Works, rev. ed., 2 vols. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1970), I, 261-88.

3Ibid., I, 263. George Steevens states that although the name of Hogarth is affixed to the print, the design is probably not by him. See John Nichols and George Steevens, The Genuine Works of William Hogarth with Biographical Anecdotes, a Chronological Catalogue, and Commentary, 3 vols. (London: Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1817), II, 311.

4Samuel Ireland, Graphic Illustrations of Hogarth from Pictures, Drawings, and Scarce Prints in the Possession of Samuel Ireland, Author of this Work, 2 vols. (London: R. Faulder, Vol. I, 1794; Vol. II, 1799).