The role of popular music in the college curriculum has always been somewhat vague and ill-defined. When, in the late 1960s, college courses in popular music were added to the traditional offerings in western art music, ethnomusicology, and jazz, the action seemed to be taken more as a response to the then frequent demand for relevance than for any specific pedagogical reasons, or because of any well-developed view that the study of popular music filled some important gap or in some way complemented the more traditional areas of musical endeavor. The cries for relevance, as useful and productive as they have been in some areas, seem to have diminished somewhat in recent years. Perhaps it is now appropriate to examine more carefully the musical relevance of popular music to the college curriculum.

The study of popular music is, perhaps before anything else, an ethnomusicological one. The "commercial" concerns of popular music do not diminish its potential as a social indicator; on the contrary, it is just these concerns, coupled with the "trendiness" of the genre and its suitability for dissemination in a mass culture, that make it such a valuable barometer of society. Popular music clearly has a place in ethnomusicological studies, right alongside the broadside ballads and the music of the street-singing Bauls of Bengal.

And yet, any approach to popular music which investigates only its social milieu would be failing to take into account its instructive value in purely musical terms. It is specifically the music of popular music which is too often neglected, whether the focus is on the popular music of another era, or on contemporary popular music. All too frequently, popular music criticism deals at length with the sociological implications of the lyrics, hair length, sadistic role-playing in performance, etc., and the musical aspects are glossed over. This is not to suggest that a musical analysis of popular music is likely to shed much light on art music for those not kindly disposed to it. The differences in context between popular music and art music are as great, or possibly greater, than between the art musics of non-western cultures. We do not study ragas and talas because we think they will necessarily aid our understanding of western art music, or even western improvisation. Similarly, it is not reasonable to assume that a study of popular music will, in and of itself, make Schubert's Lieder more accessible.

What popular music can do is to demonstrate, perhaps more clearly than any other music, the evolution or assimilation of a particular style. This cannot be done if popular music is approached via a survey of trends. Rather, any investigation must concern itself with a methodical study of musical causes and effects. Popular music is, because of its generally accessible and frequently guileless musical content, an ideal subject for a methodological study. Lineages and influences may be traced with relative ease in popular music, and the problems of defining the salient features of a style can be dealt with more easily here than in connection with music of greater complexity and lesser familiarity. The skills acquired in such an investigation may be applied to other, perhaps more sophisticated music when experience allows. The student is not learning about the use of specific chords or melody types in order to apply that knowledge to art music. Instead, he is learning that, while style in music is a relatively fluid thing with many possible sources and influences, a methodical approach incorporating both historical and theoretical concepts can be brought to bear in such a way as to increase sensitivity to that style and the ability to perceive it.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that the perception of style is at the root of any musical study. Therefore, the study of style in popular music is relevant not only to ethnomusicology, but to any area where the refinement of an investigative method is of paramount importance, e.g., music appreciation, music history, or even introductory courses in musicology.

This study of the ballad style in the early music of the Beatles is an attempt to demonstrate some of the possibilities inherent in the investigation of popular music and, in particular, its ability to assimilate various influences and styles.

When the Beatles came out with their first single, "Love Me Do," in November 1962, it must have been difficult to determine exactly what sort of group they were. The Lennon-McCartney composition "Love Me Do" resembled nothing on the English or American pop charts of the period in its apparent disregard for the conventions of pop or rock melody, its preoccupation with perfect intervals in the two vocal parts, and its slightly blues-influenced and distinctly non-virtuoso harmonica solos. This song may well have derived from the country and western ballad style of 50s rockabilly singer Carl Perkins and resembles his "I'm Sure to Fall" in melodic conception, rhythm, and textural devices as shown by an early Beatles' recording of the song. In this version of "I'm Sure to Fall," based closely on the original, the melodic phrasing and use of parallel perfect intervals in the vocal parts in particular point to the Beatles' later "Love Me Do."

After this rather ambiguous beginning, it soon became clear that the Beatles were destined to be successful hit-makers in three reasonably distinct styles. The first of these was the pop-rock style. The Beatles' first several hits demonstrated this style, a combination of tuneful melody of distinctive contour and an energetic, uptempo rhythmic accompaniment characteristic of the more improvisatory rock styles since the mid-1950s. This style can be heard in the Beatles' second single (the first to reach the number one position in England), a song heavily influenced by the vocal sonorities of the American duo, the Everly Brothers, entitled "Please Please Me." This Lennon-McCartney composition features a vocal style in which the strongly directional melody is juxtaposed with a reiteration of the tonic, a gesture recalling the 1961 Everly Brothers' hit "Cathy's Clown."

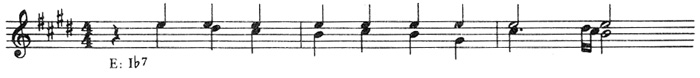

Ex. 1. Please Please Me

(A Section)

The second of the Beatles' three early styles is the rhythm and blues-rock style. This style combines the fragmented melodic style of the blues tradition (including the flatted thirds and sevenths associated with that idiom) with the limited harmonic variety of the traditional blues progression. The Beatles recorded relatively few original compositions in this style (none of the Beatles' early compositions follows the blues progression exactly), but an early American single, "I Saw Her Standing There," may, with its insistence on the tonic and flat seventh scale degrees and its blues-like harmony, be taken as representative of the type.

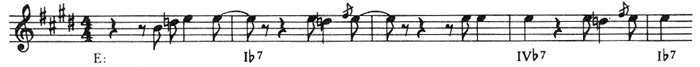

Ex. 2. I Saw Her Standing There

(A Section)

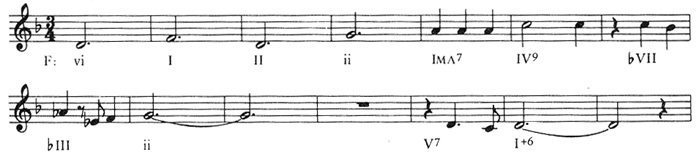

The third of the three early styles is the slow or medium tempo ballad. It must be noted here that the term "ballad" is not, in this case, meant to imply any connection with the traditional western folk repertoire nor to suggest the presence of narrative text content. Rather, the term is used here to denote those songs exhibiting a more sustained and lyrical melodic approach in combination with a comparatively slow tempo. This type is encountered in the Beatles' original repertoire almost from the beginning. The B side of the Beatles' first single, "P.S. I Love You," demonstrates in embryonic form some of the conjunct parallel progressions and augmented chords which are to mark most of the Beatles' early ballads. This type of ballad is fully and consistently realized for the first time in "Do You Want to Know a Secret?," a 1963 Lennon composition. This song appears to be modelled harmonically after Tony Sheridan's "Why?," recorded in Hamburg, Germany, at a 1961 session for which the Beatles provided some background accompaniments.

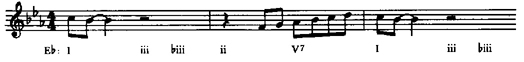

Ex. 3. Do You Want To Know A Secret?

(A Section)

(A Section)

Not only are the harmonic progressions and melodic rhythms comparable for the first few measures, but the arrangements of the background vocal harmonies also show a definite resemblance.

This archetypal ballad style is followed in a number of other ballads in this period. "If I Fell" contains an A section which makes conspicuous use of a conjunct progression featuring the mediant chord, and "Ask Me Why" consists harmonically of a slight reshuffling of the same conjunct progression which characterizes Sheridan's "Why?" and Lennon's "Do You Want to Know a Secret?"

The emphasis on the mediant chord, conjunct chord progressions, or even the chromatically descending harmonies of "Secret" were not, of course, the exclusive property of either Sheridan or the Beatles. Several rock ballads of the 50s (and earlier) had made conspicuous use of similar harmonic devices, most notably "I'm Mr. Blue," "Blue Velvet," and "You Belong to Me." The conjunct chord progression (and attendant melodic options) had not been restricted to early rock ballads, however. Meredith Willson's "Till There Was You," a song recorded by the Beatles on their earliest album, prominently features such a progression. Nevertheless, the degree to which these Beatle ballads exhibit a homogeneous melodic-harmonic content must be considered unique, even though the homogeneity frequently extends only to the first section of the songs.

Along with these generally lyrical ballads, the Beatles also composed and recorded in a ballad style which may be described as an "uptown" rhythm and blues style.1 The "uptown" style, as manifest in the work of black groups such as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles and the Shirelles, demonstrated a preference for dramatically placed minor chords (usually within the context of a major key) and a call and response vocal interaction, as well as a generally more serious and accusing tone. Although the uptown ballad style, heard, for example, in the Beatles' "No Reply," disappeared from their repertoire by late 1964, the style is important in connection with the emerging tendency of the Beatles to develop a personal synthesis of pre-existing styles. Beginning in 1964, the Beatles recorded a number of compositions which clearly demonstrate melodic-harmonic characteristics of both the rhythm and blues-rock style and the uptown rhythm and blues style. These contrasting styles can be seen in the Beatles' sixth single, "Can't Buy Me Love," which exhibits the melodic-harmonic style of the rhythm and blues style in the A section, while relying heavily on the minor mediant and submediant chords so characteristic of the uptown style in the bridge section.

Despite the fact that the Beatles had, by late 1964, proven themselves to be versatile composers and performers capable of drawing upon or synthesizing any number of different styles, there is no doubt but that the world of pop music was caught very much off-guard by the appearance of the Beatles' "Yesterday." It is probable that "Yesterday," first released as part of the British Help! album in 1965, was considered unique more for its accompanying string quartet than for its melodic-harmonic content. Although the use of strings per se was not an unusual gesture in rock music, the pseudo-Classical style used by the quartet in "Yesterday" was authentically innovative.

Still, the melodic-harmonic style of McCartney's "Yesterday" must also have been perceived by most listeners as demonstrative of a break in the Beatles' style. While McCartney's earlier ballad "And I Love Her" had exhibited an unusual use of nonharmonic tones and minor seventh chords, and more recent ballads had displayed a higher-than-usual number of augmented chords and an occasional major seventh chord, the majority of early Beatle ballads had remained securely within the stylistic parameters of the earlier rock and roll ballad as represented by Sheridan's "Why?" "Yesterday" seemed to represent the first major departure from this style in its conspicuous use of sustained nonharmonic tones and minor seventh chords. With "Yesterday," the Beatles appear to have moved into the world of the sophisticated adult commercial ballad, a fact substantiated by the large number of adult ballad singers who recorded the song and the widespread acceptance of the song among post-teenagers.

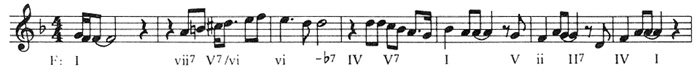

Ex. 4. Yesterday

(A Section)

And yet, the apparently revolutionary qualities of "Yesterday" were not, in fact, revolutionary for two reasons: first, the song retains significant rock ballad and pop-rock characteristics to an even greater extent than did earlier songs such as "And I Love Her"; second, the Beatles had actually composed in this adult commercial ballad style much earlier in their career, although these works were not recorded by them.

The traditional rock ballad and pop-rock characteristics found in "Yesterday" include the prominent use of the vi-V-IV progression in the bridge (with the same chords suggested in the A section), and the flat third relationship between major chords heard in the closing measures of the A section. The first of these characteristics is particularly associated with the older rock ballad style, while the second is found to any great extent only in earlier Beatle pop-rock songs.

The apparent stylistic inconsistency of "Yesterday" should not be seen as evidence of naivete on the Beatles' part, however. The fact that this song was accepted so widely as an adult popular ballad is proof of its credentials in that style; and it seems probable that the Beatles, and McCartney in particular, were well aware of the hybrid quality of the song since the group had, three years earlier, composed works which fit the adult ballad mold much more closely. In fact, two of the Beatles' earliest ballads, both dating from 1963 or before, are remarkable for their demonstration of a mature adult commercial ballad style. The first of these, "Love of the Loved," was composed for pop ballad singer Cilla Black and exists only in a rehearsal version by the Beatles released as a bootleg record.

Ex. 5. Love of the Loved

(A Section)

This song is remarkable in a number of respects. First, its harmonic variety is unusual for an early Beatle composition. While the opening tonic-mediant progression is appropriate to the rock ballad style as well as to the adult ballad style (as shown by such ballads as "Ask My Why" and "Do You Want to Know a Secret?"), the flat mediant, minor subdominant, and flat submediant chords which follow clearly distinguish the song from the commercially released original ballads as well as from the somewhat simplistic pop-rock hits of 1963 and 1964. These varied and relatively sophisticated harmonies, found in both sections of the song, clearly belong more to an older ballad tradition (as exemplified by such songs as "We'll Be Together Again" and "Blue Moon") as does the extensive, near-sequential repetition of melodic motives also found in both sections.

A second and equally remarkable example of the adult commercial style in the Beatles' early ballads is found in "It's for You," also composed for Cilla Black in 1963. The first section of "It's for You" features prominent major and minor seventh sonorities within a harmonic progression generated by a descending bass line, a device which is to become extremely important in Beatle songs composed three or four years later, and which is also encountered in Scott's "A Taste of Honey," an adult commercial ballad recorded by the Beatles on their first British album.

Ex. 6. It's for You

(A Section)

The bridge of "It's for You" is of equal interest. It exhibits a repeating "jazz waltz" rhythm combined with prominent minor added sixth, minor seventh, and diminished harmonies, and an expanding melodic motive. Once again, the song recalls the sophisticated adult ballad to a far greater extent than it does the more or less stereotyped rock ballads which the Beatles chose to record for the first three years of their career.

Nevertheless, the appearance of this relatively sophisticated style in the Beatles' early work is not as remarkable as one might suppose judging from the group's original recorded repertoire. In fact, the Beatles' experience with this style is not restricted to the recording of two musical comedy tunes on their earliest albums but dates back to the group's earliest stages. In a 1959 letter to a local journalist, McCartney states that the group "derives a great deal of pleasure from re-arranging old favourites ('Ain't She Sweet,' 'You Were Meant for Me,' 'Home,' 'Moonglow,' 'You Are My Sunshine' and others)."2

Of these examples, only "Moonglow," with its chromatic harmonies, actually qualifies as an adult commercial ballad; but the Beatles had relied on other commercial ballads for their subsequent recording auditions including "Besame Mucho," and "Red Sails in the Sunset" as well as "Till There Was You."

The Beatles' apparent enthusiasm for the older and somewhat more sophisticated ballads is generally attributed to two factors. First, the Beatles' early skiffle phase had taught them the advantages of adapting songs of various types to their own style. Second, adult influence may well have played a major role in the Beatles' early repertoire. Paul's father had led a dance band in the 1920s and it is possible that Jim McCartney's commercial tastes were passed on to his son. Paul was, in fact, the featured vocalist on all of the Beatles' early efforts in the commercial style, a probable indication of his personal enthusiasm. Two other adults were in an even more influential position in respect to the Beatles' repertoire. According to Beatle biographer Hunter Davies, both manager Brian Epstein and producer George Martin encouraged the Beatles to perform the older ballads despite the fact that the Beatles' local reputation had been based on a more dynamic approach to traditional rock and roll.3

While the Beatles' early influences offer a possible explanation for their occasional adoption of the commercial ballad style, they do not explain why the Beatles should reserve their own rather unique compositions in that style for other performers, while recording themselves only those original ballads which tend to more closely fit the formulas of the traditional rock ballad.

The reasons for this unusual situation cannot be stated with certainty but two factors may be involved. Although the Beatles, in the early stages of their recording career, were in no position to ignore the counsel of their adult advisors, there is no question but that the members of the group shared a distaste for the slick ballad style of the then popular British singer Cliff Richard. While the Beatles apparently felt that the recording of commercial ballads such as "Till There Was You" and "A Taste of Honey" demonstrated their versatility, it is possible that the group made a conscious effort to shun the slicker style in their recordings of original material in order to avoid the almost inevitable comparison with Richard.

A second and perhaps more significant factor involves a conscious decision on the Beatles' part to incorporate only the simplest devices of melody and harmony in the early recordings. While the more typical rock ballads such as "Ask Me Why" and "Do You Want to Know a Secret?" are not completely devoid of stylistic surprises (the Beatles also having vowed to eliminate overworn cliches in this period4), the songs are clearly not equal in sophistication to the adult commercial ballads "Love of the Loved," "It's for You," and the later "Yesterday." The Beatles actually seem to have experienced a mild identity crisis in connection with the complexity of their compositions. Writing in his 1964 biography The True Story of the Beatles, Billy Shepherd states:

At one time, the pair were afraid they were losing their touch as songwriters. This was because they became too obsessed with chord content. They put too much into each melody and when it came to running through the finished product, they realized it was much too complicated to catch on with the fans. It took a long time for them to realize where they were going wrong. Then they agreed: "We go for simplicity in the future. Let's stop kidding ourselves that we're great musical composers. Let's just get the sort of material that we like to sing and then stick them into the programmes."5

Shepherd also quotes Lennon on the subject of complexity:

"Sometimes we strayed outside the bounds of the simple stuff—and we worried about it. For instance, 'From Me to You' was a bit on the complicated side. Actually, we both thought it would never catch on with the fans, and I think it was Paul's dad who persuaded us that it was a nice little tune. . . ."6

An unusual awareness of audience expectations is implicit in the Beatles' attitude at this point. The relatively slick and complex adult commercial ballads were appropriate only for nightclub singers such as Cilla Black who drew upon a wider range of ages for their following, while the Beatles could expect continued success only if it were clear that their songs were directed specifically at the teenage fans who first embraced them. It was not until the Beatles were solidly launched on their most successful career that they allowed their more sophisticated efforts to become closely identified with the group as a performing entity. Their continued popularity after 1965 suggests that their decision to publicly expand their resources was a wise one even though there have been, and will probably continue to be, critics who assert that it was the early, supposedly naive Beatles who made the greatest contribution to popular music.

DISCOGRAPHY

In Alphabetical Order (Performers in parentheses)

Can't Buy Me Love (The Beatles) on A Hard Day's Night, United Artists UAS 3366A

Cathy's Clown (The Everly Brothers), Warner Bros. 7110

Do You Want to Know a Secret? (The Beatles) on The Early Beatles, Capitol ST 2309

If I Fell (The Beatles) on A Hard Day's Night, United Artists UAS 3366A

I'm Sure to Fall (The Beatles) on Yellow Matter Custard, Trademark of Quality TMQ 71032

I Saw Her Standing There (The Beatles) on Meet the Beatles, Capitol ST 2047

It's for You (Cilla Black), Capitol 5428

Love Me Do (The Beatles) on The Early Beatles, Capitol ST 2309

Love of the Loved (The Beatles) on The Beatles: L.S. Bumblebee, Contraband (matrix) 3626

No Reply (The Beatles) on Beatles '65, Capitol ST 2228

Please Please Me (The Beatles) on The Early Beatles, Capitol ST 2309

P.S. I Love You (The Beatles) on The Early Beatles, Capitol ST 2309

A Taste of Honey (The Beatles) on The Early Beatles, Capitol ST 2309

Till There Was You (The Beatles) on Meet the Beatles, Capitol ST 2047

Why? (Tony Sheridan) on In the Beginning: The Beatles (Circa 1960), Polydor Stereo 24-4504

Yesterday (The Beatles) on "Yesterday" . . . and Today, Capitol ST 2553

1This term is taken from Charlie Gillett's The Sound of the City: The Rise of Rock and Roll (New York: Outerbridge & Dienstrey, 1970).

2Hunter Davies, The Beatles: The Authorized Biography (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1968), p. 69.

3Ibid., p. 149.

4Jonathon Cott, "John Lennon" in The Rolling Stone Interviews, Paperback Library Edition (New York: Coronet Communications, Inc., 1971), p. 199.

5Billy Shepherd, The True Story of the Beatles (New York: Bantam Books, Inc., 1964), p. 78.

6Ibid., p. 79.