During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, numerous treatises on music made the analogy between musical composition and Greek and Latin theories of oratory and rhetoric.1 After all, the stirring of emotions and the qualifications of affects in the Baroque era in general were hardly the exclusive domain of music; they were also the domain of the application of word and idea to oration and literature. It would seem a reasonable assumption that the analogy between figures of speech and figures of music—designated as the "Figurenlehre" and neatly categorized by German music theorists—was taken for granted by French Baroque theorists and musicians alike. The writings of music theorists in France during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries imply a widespread knowledge of the tools of oratory, the teachings of the ancients, and techniques for the expression of the passions, although the French never set down an explicitly precise system of musical-rhetorical thought, as German theorists did. This fact should not surprise us because much the same thing is true in other countries such as Italy, where the Greco-Latin culture prevailed as an unchanging, unbroken heritage. Because of the encroachment of all things classical upon language and drama (a fact that is particularly applicable to the tragédie lyrique, which was considered by its creators and its audience alike primarily as a stylized version of the tragedy), the rhetorical figures presumably would have appeared obvious to the French composers and would not have required classification or explanation. The somewhat greater cultural remoteness of the Germans from this classical tradition might explain their need for codifying the same concepts that would have been obvious to the French and to the Italians as well.

The above simplified explanation of the role of rhetorical figures in France will be augmented somewhat in the following paragraphs by a general discussion of rhetoric in French society, in which a link between the language of the theater and that of music will be drawn. A discussion of the writings in music theory will follow, substantiating the influence of rhetoric upon French musicians. Finally the function of musical-rhetorical figures in the tragédie lyrique from Jean-Baptiste Lully through Jean-Philippe Rameau will be considered.

RHETORIC IN FRANCE IN THE

SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French society,2 an educated person learned some sort of rhetoric and practiced it in both the disciplines of speaking and writing. The importance of rhetoric cannot be overstated; along with grammar and logic it made up the trivium of the liberal arts, the essential components of study for a society that placed great significance on conversation and letter writing. Understanding French society of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, therefore, is essential for understanding the reasons why rhetoric was used so extensively. Rhetoric—the art of speaking well and the art of persuasion—was that part of a man's education most relevant to his functioning within society. It was generally agreed that one need not be an expert on a subject in order to persuade others to change their minds or to take an appropriate course of action. In addition by means of rhetoric one could appear knowledgeable without necessarily being knowledgeable. This fact explains the reasons for the accusations of shallowness bestowed upon the use of persuasive language by less understanding generations. Particularly during the age of Louis XIV the end would have justified such superficial means because of the attention focused upon the social virtues. Therefore the educated man of the day would have used rhetoric and would have been influenced by it at court and in theaters, schools, salons, churches and halls of justice.

Rhetoric was not only a functional device; it was considered an art of decoration as well as of persuasion. In an age characterized by objectivity and intellectualism, decoration in speech and literature was not necessarily subordinated to the supremacy of "reason" and maintained a place at the court of Versailles along with painting, sculpture, architecture, spectacle, and stage design. Despite condemnations of ostentation by some purists, both simplicity and elegance of language influenced the formulation of the precepts of rhetorical techniques.

The rhetorical theories absorbed from the classical inheritance—the writings of Aristotle, Cicero, Quintilian, Demosthenes, and Vergil—were of particular interest to French dramatists because a relationship between the rostrum and the theater, the orator and the actor, was generally acknowledged. The actor might copy the orator, as was suggested by Jean Léonor le Grimarest who stated that "the actor ought to consider himself as an orator who makes a speech in public in order to move the listener."3 Quintilian's Institutio oratoria was used as a guide, for its division of rhetoric into five parts—inventio (what to say), dispositio (the order in which to say it), elocutio (how to say it), memoria (memory), pronunciato (diction and gestures)4—were all pertinent to the theater. Of considerable importance to the dramatist would have been inventio, which includes the loci topici, formulas and outlines for possible sources of material or generally accepted precepts of wisdom, such as maxims.5

The second area of Quintilian's rhetorical theory that would have been of major interest to the dramatist—and ultimately to the creators of the tragédie lyrique—was elocutio; this phase of the orator's art included the figures of speech that enable the speaker or writer to arouse passions within the audience and to impress with eloquent language used for its own sake. In the theater these two purposes of rhetorical techniques—the functional and the decorative—frequently came into conflict with one another during the generation of Thomas Corneille and Jean Racine, yet both intentions survived and were not mutually exclusive.6 For instance, Racine, who received a thorough training in rhetoric,7 succeeded in combining the functional with the decorative point of view. The intention of the French tragedy was both to move and to please, but fine language was permitted only if it was essential to the impression of reality and to the expression of the characters' passions on the stage. Therefore to Racine the tragedy could be passionate and expression could be eloquent, but the simplicity and clarity of the dramatic construction had to be kept intact.

MUSIC THEORISTS ON RHETORIC

As in the case with Racine's writings on rhetoric where there are few statements concerning the playwright's theories, there is little theoretical exposé on musical-rhetorical figures in France. Again, the approach that rhetorical figures in music were the assumed knowledge of composer, theorist, and audience must be reaffirmed. French music treatises, however, imply a widespread use and knowledge of the figures even though they do not elucidate a precise system of codification.

In the first place it is certain that music theorists thought of music as an oratorical art in the same light that Grimarest considered the orator and actor as sharing a common bond. For instance, in 1636 Marin Mersenne made this analogy in the Harmonie universelle: "First of all, it is necessary that he [the musician] imagine that he is an Orator who forgets nothing in his oration of everything that he believes can serve him in pleasing his listeners and can move them to that which he wishes."8 Nearly a century later Rameau described the musician in much the same terms in his Traité de l'harmonie: "A good musician should surrender himself to all the characters he wishes to portray. Like a skillful actor he should take the place of the speaker, believe himself to be at the location where the different events he wishes to depict occur, and participate in these events as do those most involved in them. He must declaim the text well, at least to himself, and he must feel when and to what degree the voice should rise or fall, so that he may shape his melody, harmony, modulation, and movement accordingly."9

Numerous writings of the eighteenth-century music theorists include references to classical models.10 Jean Pierre Crousaz's Traité du Beau, for instance, contains an entire chapter on eloquence and includes comments on the oration of Cicero.11 In addition Michel-Paul de Chabanon's two treatises, Observations sur la Musique12 and De la Musique considérée en elle-même et dans ses Rapports avec la Parole,13 allude to the relationship between music and the oratorical vocabulary of the ancients. In the Observations Chabanon cited Cicero and Quintilian as models;14 although he expounded on the differences between song and discourse the theorist felt that music and declamation shared the common features of the alteration of the voice and the gesture and expression of the face.15 In Chabanon's second treatise De La Musique, the theorist reaffirmed the importance of the Greek writings on elocution16 and listed principles from Quintilian in describing the oratorical accent.17 More significant perhaps is that Chabanon saw music in union with a text and that the one commented on the other. For instance, the construction of grammatically balanced phrases was considered a very musical property,18 and the repetition of the same text within the air would be a natural thing to do when one repeated the same melody.19

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was generally agreed that the orator's or actor's ability to arouse the affections of the audience was part of the basic doctrine of rhetorical figures. With regard to music's role in the art of persuasion, the French music theorists were in agreement, if not particularly detailed. Philosophers in general and music theorists in particular described the affections as very precise passions or types of emotion; rhetorical figures, however, were not restrictive in the types of expressions conveyed, for they depended upon the particular emotions of the text. These devices were considered in both a musical and textual context and were in keeping with the general sentiment that was to be communicated.

The Baroque theorist's fixation with the passions that was expanded into a doctrine on musical rhetoric emerged from a significant French philosophical source, René Descartes' Les Passions de l'âme.20 Descartes' thesis was the definition of passions of the human spirit which in turn could cause some specific reaction in certain parts of the body; from the definition of the passions Descartes codified six primitive passions and a number of principal emotions. With regard to classifying musical affect,21 Mersenne in the Harmonie universelle correlated sounds with tastes, smells, colors, shapes, and sizes and associated consonances and dissonances with the four elements and the seven planets.22 The emotional properties of the modes was one of the most universally recognized affective devices, and Rameau,23 Charles Masson,24 Antoine Parran,25 and Michel Pinolet de Montéclair26 all correlated this contrivance with the change in the indication of sentiments. The expressive qualities of the intervals, as well as numerous other musical devices, and their ability to portray different moods, likewise supported the case for text illumination; these also received attention in the treatises. For instance, Bernard de la Cépède, in La Poétique de la Musique, suggested that an impression of sorrow may be conveyed with small intervals.27 Rameau's Traité elaborates on the unquestionable ability of chords—with their extremes of consonant and dissonant qualities—to arouse different passions.28 In a later treatise, Observations sur notre Instinct pour la Musique, Rameau added that ornaments are specifically expressive because they emphasize the main words of the verse.29 In addition Chabanon's Observations proposes that all such natural devices for producing sensation were at the disposal of the composer and that the music could alternate its various impressions by alternating different articulations and dynamics within the same piece. Chabanon's thesis is particularly pertinent to the case for rhetorical figures because of the theorist's application of these techniques to music with texts.30

Indeed, French theorists were precise about oratory, accent, and affection, but as has been mentioned detailed codification of specific musical-rhetorical figures did not receive their attention. However, it seems certain that rhetorical figures are what these theorists had in mind, particularly with regard to the correlation of a figure of speech such as repetition with a musical device (see above, Chabanon's statement on repetition of text and melody). Descartes' Compendium musicae further supports the case for musical-rhetorical figures by explaining that there are "figures of speech in music, just as there are figures of speech in rhetoric" and sequence and imitation belong to this category.31 Rameau perhaps was the most specific of all the French theorists when he described two figures in his Traité: "Languor and suffering may be expressed well with dissonances by borrowing and especially with chromaticism. . . . Despair and all passions which lead to fury or strike violently demand all types of unprepared dissonances, with the major dissonances particularly occurring in the treble."32 With regard to the use of chromaticism to express anguish and sorrow, Rameau probably was describing what the German theorists had labeled "pathopoeia." Unprepared dissonances, used in conjunction with texts of intense emotional reaction, would have been referred to as "quasitransitus." That Rameau did not use these terms does not imply that he was unaware of them.

RHETORICAL FIGURES IN THE Tragédie lyrique

In Germany the vocabulary of musical speech was gradually codified between the years 1599 and 1788 in over 25 theoretical sources that define approximately 100 rhetorical figures. In the tragédie lyrique from Lully through Rameau, over two dozen different figures appear with enough frequency that their significance is unquestionable.33

The musical-rhetorical figures of the tragédie lyrique exhibit the two distinct although not mutually exclusive classifications found in Racine's classical tragedies: first that which decorates by means of the arrangement of phrases into various patterns (pattern rhetoric), and second that which incites the passions and directly or indirectly expresses emotion (functional rhetoric). Additionally the embellished style is reinforced by a category of figures that is blatantly pictorial, that labeled "hypotyposis" or word-painting, which will be dealt with first.

Musical-rhetorical figures of the hypotyposis category can be related indirectly to the poetic figure of onomatopoeia in which words are formed with sounds that resemble those emanating from some object or action. In both speech and music the relationship between sound and its object or action is merely suggestive. An exhaustive list of all the figures of word-painting would be impossible to prepare, as the potential for expression is limited only by the composer's imagination. One quite typical example is an ascending stepwise melodic line in notes of equal value coupled with a text denoting exultation or ascent; this figure has been referred to as ''ascensus" or "anabasis." By far the most frequently employed hypotyposis figure in the tragédie lyrique is the opposite of the ascensus, the descending stepwise melodic line used in conjunction with texts of depravity or descent. This figure has been labeled "descensus" or "katabis" in German theoretical treatises.

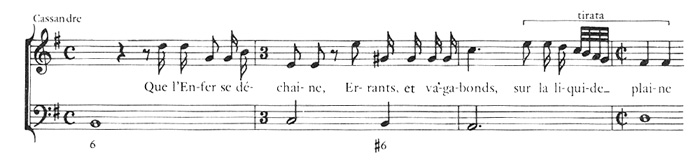

A distinction can be drawn between the two previously mentioned word-painting figures and that designated as the "tirata," which is a rapid stepwise progression, often a scale encompassing a sixth or as much as an octave in either ascending or descending motion. The tirata usually occurs with words such as lancer or éclair, but in a recitative from Thomas Bertin de la Doué's tragédie Ajax34 (Ex. 1), this figure occurs with the word "liquide."

Ex. 1. Thomas Bertin de la Doué: Ajax, Act I, scene 7.

The example is particularly interesting because of the combination of two rhetorical figures, one exclusively musical and the other exclusively poetic. The descending rapid burst on the word "liquide" denotes fluidity, but the phrase "liquide plaine" is a more frequent and stylized figure in the texts of the tragédie lyrique, the periphrasis. Quintilian classified the periphrasis as a trope in which several words express something in fact where fewer or only one word (such as la mer in this case) would be needed.35 In this example with the tirata the periphrasis merely embellishes, but in other examples it could be interpreted as a source of additional information that assists in qualifying or describing.

Pattern rhetoric, the second category of musical-rhetorical figures, is, like the word-painting category, primarily decorative. Pattern rhetorical figures are emphatic in that most involve some sort of repetition or at least some structural arrangement into various configurations. With regard to the repetitive figures in musical forms, the repetition consists of phrases or motives and occurs in the same voice. Musical figures of repetition are directly correlated with poetic figures of repetition and therefore their labels are borrowed directly from classical rhetoric. The emphasis is most significant when the original text and the music both employ repetition, but in general repetitive musical figures result from the composer having selected those words to be repeated. In any respect repetition was acknowledged as both a rhetorical device and a structural device by the composers of the tragédie lyrique, for repetition of phrases and periods characterizes a number of the small closed forms within the scenes of the tragédies. In cases where the text sentiment demands particular emphasis, such as the conclusive generalizing statement of the maxim air, the repetition is rhetorical.

Repetition of a phrase at the same pitch level, either as a nonsuccessive melodic motive or as an ostinato repetition in the bass, has been labeled by music theorists "anaphora." In speech the anaphora figure serves as a model in which marked repetition of a word or phrase occurs in successive clauses or sentences. In the tragédie lyrique a logical place for the anaphora would be in the varied repeat of the B section of the dialogue air in A-B-B' structure, a form common to the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French music drama. Because the dialogue air was indispensable to the commentary, and filled in details necessary for the comprehension of the tragédie, the repetition would be regarded as a persuasive device and not merely as a structural one. The anaphora is perhaps more emphatic when used in solo or multiple recitative. Rameau used the figure at a point of extreme dramatic intensity in Hippolyte et Aricie36 (Ex. 2).

Ex. 2. Jean-Philippe Rameau: Hippolyte et Aricie, Act IV, scenes 3 and 4.

In this decisive passage it is the chorus that repeats the key phrase "Hippolyte n'est plus." The crowd of attendants on stage at this moment reacts to Hippolyte's death, and the choral fragments bind together the dramatic impact of the entire scene in which Phèdre herself confronts the consequences of her disastrous actions.

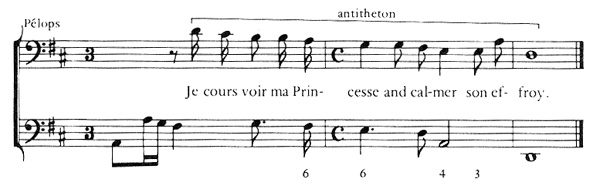

The pattern rhetoric of classical models encompasses nonrepetitive figures, specifically the antithesis. This rhetorical figure involves the arrangement of words that emphasize a contrast, such as the statement "Crafty men condemn studies, simple men admire them, and wise men use them." In music that labeled the "antitheton" refers to some sort of successive contrast, such as a contrapuntal contrast between theme and countertheme, consonant and dissonant harmonies, polyphonic and homophonic texture, diatonic and chromatic line, high and low register, major and minor tonalities, loud and soft dynamics, or just about any contrast between sections or entries. The dramatic fluctuation that is inherent in the scene structure of the tragédie lyrique frequently is characterized by contrast, and therefore the antitheton is an important and diverse rhetorical figure of the lyric drama. One form of the antitheton emerged in the context of the rhythmic design; the shifting meters and note values indicative of the simple recitative style often provide opportunities for contrast. Example 3 from Hippodamie37 by André Campra, displays a simple recitative in which the anapestic rhythm of eighth- and sixteenth-note motion gives way to a slower quarter- and eighth-note movement. In this manner the character of Pélops is able to express two opposing concepts: "cours" and "calmer."38

Ex. 3. André Campra: Hippodamie, Act IV, scene 5.

Musical-rhetorical figures in the tragédie lyrique may be categorized as functional in that they are direct expressions of the passions; these assist in establishing a balance with the decorative rhetoric of the repetition figures and other devices of structural arrangement. The stirring of the affections and the direct expression of the passions were conveyed by the composers of the tragédie lyrique with a variety of techniques: first that in which contrapuntal design between two or more voices emphasizes a particular sentiment, second that in which the melodic line draws attention to a word with some unusual feature of style, third that in which the harmonic dissonance serves to emphasize the text, fourth that in which rests are used to illuminate word meaning.

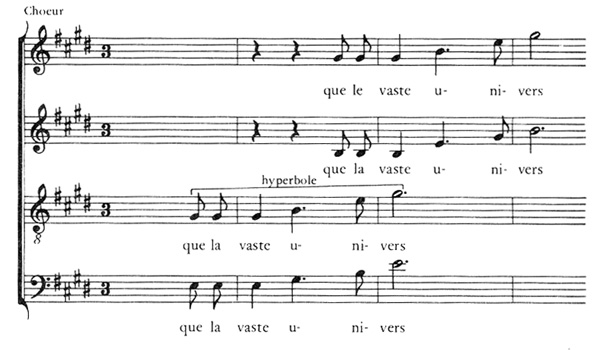

Most of the contrapuntal writing of the four-part choruses of the tragédie lyrique is void of rhetorical content because of the comparatively superficial nature of the texts. Musical-rhetorical figures involving a counterpoint between two or more voices, therefore, do not occur with any great frequency but one such figure derived from classical rhetoric and referred to by music theorists as the "hyperbole" should be mentioned here. In speech the hyperbole incorporates exaggerated terms in order to emphasize rather than to deceive; it serves as a functional figure because it is a recognized device for the expression of violent emotion. In the French classical tragedy, the hyperbole is often difficult to isolate because so much of the drama is characteristically an exaggeration and character expressions are often extreme. In the tragédie lyrique the emphatic nature of the hyperbole is less vehement but may be used to display excessive height and loftiness or depth and depravity. The musical hyperbole occurs with the extension of the normal range of the voice. In Example 4 from Pyrame et Thisbé39 by François Rebel and François Francoeur, the hyperbole presents itself as the two lower voices of a four-part chorus ascend into the range of the upper two voices.

Ex. 4. François Rebel and François Francoeur: Pyrame et Thisbé, Act II, scene 4.

The wide range of the melodic motive reinforces the sentiment of the text "le vaste univers." Because this figure is aligned with the first appearance of that particular arpeggiated melodic motive, its overlapping of ranges is presumably of rhetorical importance.

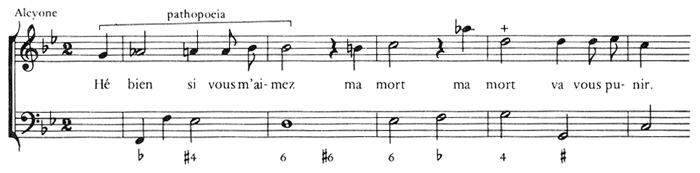

Startling devices within a melodic line are the most common types of figures of functional rhetoric in the tragédie lyrique; a number of these might have been recognizable to the listener familiar only with classical rhetorical theory. For instance, the musical figure designated as "pathopoeia," which refers to any expression of passion in classical rhetoric, is linked with an ascending or descending chromatic progression. In the tragédie lyrique examples often employ a chromatic bass; when the bass and melodic line are identical the correlation between the poetic and the musical figures is clear. In Example 5 from Alcyone40 by Marin Marais, the pathopoeia is exclusively a melodic device.

Ex. 5. Marin Marais: Alcyone, Act V, scene 1.

The ascending chromatic figure spans a range of a perfect fourth and is used in concurrence with two other emphatic techniques: text repetition and the descending diminished fifth interval on the words "ma mort."

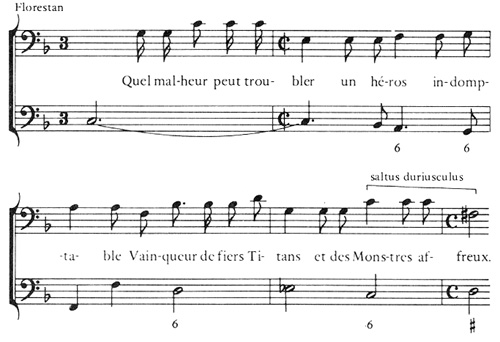

The descending diminished fifth from Example 5 exemplifies yet another approach to functional rhetoric and another type of melodic emphasis figure, which has been labeled the "saltus duriusculus." This figure of purely musical significance, the single most prevalent rhetorical device in the tragédie lyrique, is defined as a harsh melodic leap. Those intervals that would have been heard as harsh and which therefore characterize the saltus duriusculus are the diminished and augmented intervals and particularly the ascending and descending diminished fourth, descending diminished fifth, descending minor sixth, descending major, minor and diminished sevenths, and intervals exceeding the octave. Lully used this figure extensively. At the opening of his tragédie Amadis41 (Ex. 6), he includes the descending diminished fifth on the phrase "Monstres affreux."

Ex. 6. Jean-Baptiste Lully: Amadis, Act I, scene 1.

This expression of emotion occurs in Florestan's discourse as he addresses the hero Amadis, reminding him of his daring past exploits. Actually Florestan is asking Amadis a rhetorical question ("What misfortunes can disturb an unconquerable hero, vanquisher of fierce giants and frightful monsters?") to which there is only one appropriate response. In this manner Florestan's question itself would make more of a mental impression than the response by Amadis.42

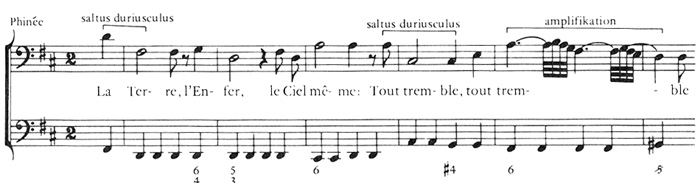

Functional rhetorical figures formulated from points of harmonic dissonance between two voices and used mainly in the recitative style appear less frequently in the tragédie lyrique than do the melodic rhetorical figures. However, several of the dissonance figures occur with a degree of regularity. One such example, referred to as the "amplifikation" or "variatio," may be regarded as either a functional figure or a hypotyposis figure, depending on the word illuminated. This device involves the correlation of a coloratura with a word of its character; it is a replacement for a longer note. Because the composers of the tragédie lyrique were so conscious of textual subtleties, it is rare to find a coloratura that exists in its own right and is not a rhetorical figure. Granted, the amplifikation was based on the purely musical configurations and mannerisms of instrumentalists and singers that the purists of the French vocal style opposed; in most cases the ornament is linked with significant words such as voler, guerre, célébrez, triomphe, and so forth. These colorful words were recognized as appropriate for musical illuminations. Jean Laurent Le Cerf de la Viéville referred to them as "mots privilégiés" and later they were called "lyriques."43 Consequently they became trademarks of the most innovative composers of the generation preceding Rameau as well as of Rameau himself. In Example 7 from Montéclair's Jephté44 the amplifikation is combined with several other musical-rhetorical figures for particular impact.

Ex. 7. Michel Pinolet de Montéclair: Jephté, Act I, scene 4.

The phrase "tout tremble" stands out in one regard because it is repeated; in addition the first statement of this phrase is treated musically by a descending minor sixth, the saltus duriusculus, and the second statement with the amplifikation. A poetic rhetorical figure, enumeration, occurs in this passage as well, with the accumulation of three contrasting localities, "la Terre, L'Enfer, le Ciel." Although the enumeration figure has no apparent musical significance, it is a device that supports the connection between the rhetorical vocabulary of Racine's classical theater and the tragédie lyrique.

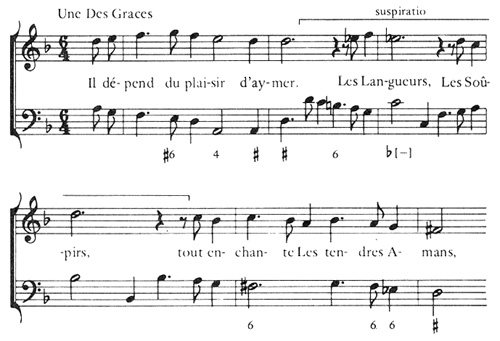

The final category of rhetorical figures is that in which rests are used as emphatic devices and as direct expressions of the passions. At times the rests are directly illustrative, particularly when the figure referred to as the "suspiratio" is involved. The suspiratio creates an obvious sighing effect with the separation of syllables or words by means of rests; it is a type of melodic diction. In most instances the suspiratio figure was used by the composers of the tragédie lyrique to strengthen dialogue and in its most conspicuous form the key word is the gasping exclamation ah. In a somewhat unusual example, Hésione by Campra45 (Ex. 8), the pauses that suggest sighing appear in a nondramatic dance song illustrative of the pleasantries of love.

Ex. 8. André Campra: Hésione, Act II, scene 5.

The rests occur after the words "les langueurs, les soûpirs." These punctuate the regularly patterned rhythm of a dance that resembles the loure. The text is subdued and the rhetorical figure, rather than functioning as an agent of intense passion, is the source of a genteel and nonpathetic sentiment.

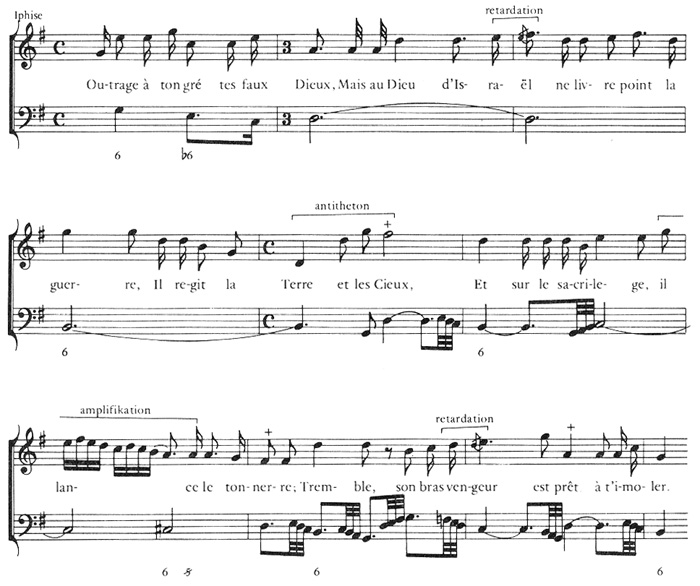

Without question some of the most dynamic passages in the tragédie lyrique are those that incorporate several different rhetorical figures along with other startling devices that draw attention to the texts. A passage of simple recitative from Montéclair's Jephté (Ex. 9) for instance, is realized rhetorically with two retardation figures, which is the upward resolution of a suspension (on the words "Israël, vengeur"), an amplifikation figure ("lance"), and an antitheton ("Terre et les Cieux").

Ex. 9. Michel Pinolet de Montéclair: Jephté, Act II, scene 2.

Embellishments are specified on the words "Cieux, tonnerre," and "prêt." In addition the affect of agitation is created by an animated bass motive consisting of dotted eighth- and thirty-second-notes, an atypical feature of the simple recitative style.

In a culture such as that of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, where both the classical and oratorical traditions were alive and intense, there would have been no need to explain or justify the theory of text expression through the use of musical-rhetorical figures. In fact the audiences which attended performances of the tragédie lyrique—the educated segment of society—probably recognized many of the musical-rhetorical figures, or at least those derived from classical rhetoric. The importance of this specific type of affective expression cannot be overstated. The technique of composing with preexisting materials implies a considerable degree of contrived objectivity, a scheme of time-honored significance. Yet this should not be surprising, because in addition to the musical-rhetorical figures the vocabulary of the tragédie lyrique depended upon contrived systems of forms, keys, melodic intervals, embellishments, harmonic progressions, meters, rhythms, and instrumentation. The presence of the rhetorical figures in the tragédie lyrique, therefore, only supports the case for a common aesthetic that prevailed in France from the time of Lully to that of Rameau. The most important aspect of this aesthetic is the rhetorical vocabulary of the ancients which carried over into the French classical theater, into the theoretical writings on music, and ultimately into the lyric drama. It is to these sources that scholars must look for a thorough comprehension of the role of classicism in the tragédie lyrique.

1For a list of primary and secondary sources see George J. Buelow, "Music, Rhetoric and the Concepts of the Affections: A Selective Bibliography," Notes 20 (1973-74), 250-259.

2For an introduction to the role, nature and significance of rhetoric in France during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries see Peter France, Racine's Rhetoric (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965) and his Rhetoric and Truth in France: Descartes to Diderot (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972). The background material in this section of the study is indebted largely to France's works.

3La Vie de M. de Molière, ed. Mongrédien (Paris, 1955), p. 162, quoted in France, Racine, p. 31.

4Quintilian's rhetorical theories are summarized in France, Racine, pp. 16-17. Cicero's Orator also illuminates these five divisions of rhetoric.

5Maxim airs, in which some general precept independent of the dramatic action is expressed, are indispensable conventions of the tragédie lyrique. Such airs occur generally in scenes of dialogue where a lesser character comments on a basic rule of love, virtue, and so forth; the result of this type of independent device is the antidramatic interruption of the action.

6France, Racine, p. 36.

7For further information concerning Racine's studies at the Petites Ecoles of Port-Royal and at the Collège de Beauvais, see France, Racine, p. 37.

8Il faut premièrement qu'il [le musicien] s'image qu'il est comme un Orateur qui n'oublie rien en son oraison de tout ce qu'il croit lui pouvoir servir pour plaire à ses auditeurs, et pour les émouvoir à ce qu'il veut." Marin Mersenne, Harmonie universelle (Paris: S. Cramoisy, 1636; facsimile reprint Paris: Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, 1963), I, 181.

9Jean-Philippe Rameau, Traité de l'Harmonie réduite à ses Principes naturels (Paris: Jean-Baptiste Christophe Ballard, 1722; trans. Philip Gossett, New York: Dover Publications, 1971), p. 156.

10The case for musical-rhetorical figures in the tragédie lyrique is strengthened by the fact that rhetoric played an important role in French painting of a slightly earlier period. It is obvious that Nicolas Poussin, for instance, was attempting to formulate a theory of art based on rhetorical thought when he wrote in his notes the following concerning the classical models: "Of action. There are two instruments which affect the souls of the listeners, action and diction. The first is so valuable and efficacious in itself that Demosthenes gave it first place over all the other devices of rhetoric, and Marcus Tullius [Cicero] calls it the language of the body. Quintilian attributes such strength and such power to it that he regards conceits, proofs and effects as useless without it. And without it lines and colour are likewise useless." Quoted and translated in John Rupert Martin, Baroque (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), p. 86. Martin's source is G.P. Bellori, Le vite de' pittori, scultori et architetti moderni (1672), pp. 460-461.

11Jean-Pierre de Crousaz, Traité du Beau (Amsterdam: F.L. Honoré, 1715), p. 290.

12Paris: Pissot, 1779; facsimile reprint Geneva: Slatkine Reprints, 1969.

13Paris: Pissot, 1785.

14Chabanon, Observations, p. xix.

15Ibid., p. 153.

16Chabanon, De la Musique, p. 403.

17Ibid., p. 436.

18Ibid., p. 209.

19Ibid., p. 213.

20Paris: H. le Gras, 1649; trans. Elizabeth Haldane, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1931.

21The classification of affects based on Descartes' definition of the passions was not restricted to the discipline of music but figured in the field of French painting as well. Charles Le Brun, for instance, consciously studied Cartesian philosophy and applied a systematized approach to character expression in his work, illustrated in a lecture presented at the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture and subsequently published in his Conférence de M. Le Brun sur l'Expression générale et particulière (1698). For more information on this subject see Martin, Baroque, pp. 88-91.

22John B. Egan, "Mersenne's Traité de l'Harmonie Universelle: A Critical Translation of the Second Book" (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 1962), pp. 18, 51, 66.

23Observations sur notre Instinct pour la Musique et sur son Principe (Paris: chez Prault fils, 1754), p. 90.

24Nouveau Traité des Règles pour la Composition de la Musique (Paris: J. Collombat, 1699; facsimile reprint New York: Da Capo Press, 1967), p. 10.

25Traité de la Musique théorique et pratique (Paris: Ballard, 1639; facsimile reprint Geneva: Minkoff Reprints, 1972), p. 117.

26Principes de Musique (Paris: Rue St. Honoré à le Règle d'or, 1736), p. 16.

27Paris: the Author, 1785; facsimile reprint Geneva: Slatkine Reprints, 1970, p. 80.

28Rameau, Traité, ed. Gossett, pp. 154-156.

29Rameau, Observations, p. 70.

30Chabanon, Observations, pp. 172-176.

31René Descartes, Compendium musicae (1618) (Utrecht: Gisbert a Zyll & Theodori ab Ackersdycke, 1650; trans. W. Robert, Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1961), p. 51.

32Rameau, Traité, ed. Gossett, p. 155.

33Of the numerous writings that discuss the doctrine of figures, two have been used as the basis for this examination of musical-rhetorical figures in the tragédie lyrique: Harold Samuel, "The Cantata in Nuremberg during the Seventeenth Century" (Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, 1963), pp. 560-576; and Arnold Schmitz, "Figuren, musikalische-rhetorische," Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Vol. 4, col. 176-183.

34Thomas Bertin de la Doué, Ajax (Paris: Jean-Baptiste Christophe Ballard, 1716); first performed at the Académie Royale de Musique on April 20, 1716.

35The effect of the trope would be the embellishment of language that otherwise would be plain, and the most significant device of such was the metaphor. Tropes include metonomy, in which the immaterial might be symbolized with its material counterpart or in which some subjective impression was developed from an objective attribute. Along with metonomy, the metaphor and the periphrasis, the epithet—a fourth type of trope—appears frequently in the texts of the tragédie lyrique.

36Jean-Philippe Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie, Oeuvres complètes, Vol. VI (Paris: A. Durand, 1895-1924; reprint New York: Broude Brothers, 1968); first performed Octobter 1, 1733.

37André Campra, Hippodamie (Paris: Christophe Ballard, 1708); first performed March 6, 1708.

38In most instances the rhythmic patterns of the recitatives of the tragédie lyrique are governed by textual rather than by musical considerations. Frequently the realization of the anapest in series of rapid note values serves as an appropriate means of quickly passing over a number of brief syllables. However, Campra assumed a much more flexible approach to the formal rigidity of the anapest by expressing the rhythm in variable note values within the same line. In order to enhance the expressivity of the text Campra would augment the note values to suggest a character's hesitancy or diminish them to portray agitation or urgency.

39François Rebel and François Francoeur, Pyrame et Thisbé (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale ms Vm2228, in-fol.); first performed October 17, 1726.

40Marin Marais, Alcyone (Paris: the Author, Hurel, H. Foucaut [De Baussen], 1706); first performed February 18, 1706.

41Jean-Baptiste Lully, Amadis, Oeuvres complètes, Pt. IV, Vol. 3 (Paris: Editions de la Revue Musicale, 1930-39; reprint New York: Broude Brothers, 1968); first performed January 14, 1684.

42The rhetorical question is an important device of the French classical tragedy. With particular regard to the tragédie lyrique, questions of a pathetic nature—if not rhetorical ones—are common. Labeled the "interrogatio" by German theorists, this musical figure is distinguished by the ending of a melodic phrase a second higher than the note for the preceding syllable.

43Cuthbert Girdlestone, Jean-Philippe Rameau, rev. ed. (New York: Dover Publications, 1969), p. 135.

44Michel Pinolet de Montéclair, Jephté (Paris: Boivin, 1732); first performed either February 28 or March 4, 1732.

45André Campra, Hésione (Paris: Christophe Ballard, 1700); first performed December 21, 1700.