Iconography of the viol was the theme of the special project for the 1978-79 academic year sponsored by the Research Center for Musical Iconography. Based at City University of New York, the Research Center is the American branch of RIdIM, the Répertoire Internationale d'Iconographie Musicale. The viol exhibit, Series B/3, is one of several ongoing projects dealing with specific segments of musical iconography, each under the supervision of individual scholars who are specialists in the subject matter of these special projects.1

Presentations of the project, in the form of exhibits and papers, were given at the eighth annual meeting of the American Musical Instrument Society at the University of Chicago on April 20-22, 1979, and at RIdIM's seventh annual international conference at City University on May 4-5, 1979. The main area of attention at these iconography sessions was an exhibit, "Autour de la viole de gambe," assembled several years ago in Paris by the Centre d'Iconographie Musicale du Centre National de La Recherche Scientifique under the supervision of Frédéric Thieck. Consisting of over 100 pictures of viols, the exhibit presents a pictorial history of the instrument during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.2 In addition, at both of these meetings several specialists on the construction and restoration, history, and playing technique of the viol led round-table discussions concerning how musical iconography can add to our knowledge of the instrument.

While Series B/3 was initiated in Paris several years ago, it was a new and very welcomed project in the New York office, for hopefully it will help spread the study of iconography of the viol to more American scholars and musicians working with the instrument. Thus far the study of pictorial representations of the viol, while quite necessary, is a relatively unexplored segment of viol research.3 The project has already revealed a great deal of information not easily obtained through nonpictorial means concerning construction of instruments (particularly Renaissance viols), questions of performance practice (especially ensemble performance and details of holding positions), and the social context of the viol among both professional and amateur musicians. I wish to present here a sample of the type of information which musical iconography provides, information which we are hard pressed to find elsewhere. I will use pictures from the RIdIM exhibit and deal specifically with Baroque paintings.

The use of musical instruments in paintings, particularly portraits, can tell us much about the social climate in which these instruments were used. As Richard Leppert has recently observed, "We can be fairly confident about the respectability of instruments in portraits for the reason that no sitter would want to be captured on canvas holding an unfashionable or disparaged instrument, any more than he would want to be preserved in other than his best attire."4 Mr. Leppert has noted elsewhere that in the body of seventeenth-century Flemish paintings which he has studied, the viol, especially as used in chamber ensembles, is generally depicted in upper class surroundings.5 The instrument was obviously highly respected by the socially elite, to the point that an artist would often keep a viol in his studio as a prop, even for those subjects who did not play the instrument. Those who did play often considered their viol important enough to be included in portraits.

Richard Leppert has primarily discussed paintings in which the viol appears as part of a chamber ensemble. In the seventeenth-century Netherlands private chamber music was the principal type of secular musical activity available to the upper classes. I wish here to complement Leppert's articles by commenting on a few portraits in which only one player is shown. As in the ensemble views, these single players are likewise of upper class status, as revealed not only by their personal appearance but also by the viols which they play and the elegant decor which surrounds them.

Approximately fifty plates in the RIdIM exhibit show viols being played or held in playing position.6 Of these about 35 include the instrument in an ensemble; the remainder are of only one player. Many of these solo portraits are of actual players. Some of these players presumably played at least some of the solo repertory. Of these soloists only two, both women, play a viol other than bass size, although there are also some females playing bass instruments.7 Most soloist portraits are by French or Dutch painters. In the entire collection there are only a few depictions of viols in lower class surroundings and none of the soloists is of such social rank.

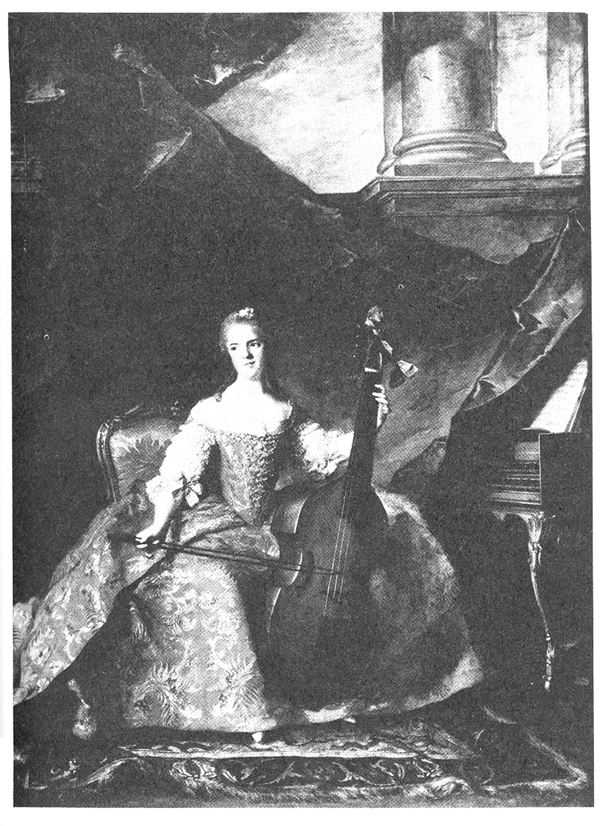

Included in the display is one of the most magnificent portraits of an individual playing a viol ever painted, Jean-Marc Nattier's representation of Madame Henriette of France playing a seven-string bass.8 (See Plate I.)

PLATE I. Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1766)

Madame Henriette Playing Her Bass Viol

(Courtesy, Musée National du Château de Versailles)

Nattier (1685-1766), who became portrait painter for the royal family in 1742, painted the work in 1754, two years after the death by smallpox of the twenty-four-year old Henriette, favorite daughter of Louis XV. Nattier himself considered it to be one of his best works.9

Seated near a two-manual harpsichord on which is perched an unidentified score, Madame Henriette plays what was reportedly her favorite instrument, a large bass viol with an elegantly carved head. Such an instrument surely would have been used for the French solo repertory of the period, such as the Pièces de viole by Marin Marais. The manner in which the young woman holds the viol is a realistic playing posture, although since the portrait was done two years after her death, we cannot be sure who or what Nattier used as his model for these details of the work. In order to hold the instrument comfortably Henriette wears a finely-detailed red and gold (brocade?) dress with a full skirt. Every aspect of her form reveals her beauty. The point of one shoe, possibly of white satin, shows below her skirt. The special sweetness of her face is indicative of the respect which Nattier must have had for her.

The decor of the room matches the voluptuousness of Henriette herself. She is seated on a beautiful chair, possibly covered with silk. On the floor is a magnificent rug. Most overwhelming is the thick drapery which hangs behind her in sweeping folds, complementing the fullness of her dress. It is difficult to determine the exact nature of the room, but the large column at the top of the picture would seem to indicate a hall in a palace.

This dazzling image of the young musician clearly indicates that Nattier knew how to flatter and elevate his subject. The prominent position of the viol in the portrait further reveals the special fondness which both Henriette and Nattier must have had for the instrument.

Of similar grandeur and sophistication is the portrait of the young Dutch violist shown in Plate II.10

PLATE II. Caspar Netscher (1639-1684)

The Young Viol Player

(Courtesy, Muzeum Narodowe, Kracow)

Originally thought to be by Jan Verkolje (1650-1693), the work more recently has been attributed to Caspar Netscher (1639-1684). Netscher lived in Holland during much of his career and significantly influenced the style of Dutch portrait painting at the end of the seventeenth century, excelling particularly in the depiction of rich dress and draperies.11 According to Pieter Fischer the work may be a real portrait, although the youth has never been identified. It is possible that the young man actually played the viol, for his playing posture is a realistic one. The viol which he holds is a six-string instrument, smaller than Henriette's but also with a carved head and with flame rather than C holes.

The young violist obviously possessed refined tastes. Richly clad in a flowing tunic, possibly of velvet, he is presented by the artist as Henriette is—as a beautiful musician, viol in hand, surrounded by only the finest of material objects and seemingly untroubled by the cares of the world. He also sits in a large building, possibly a palace. Other objects in the portrait indicate cultural refinement and musical taste. On his left lie an open score and a violin on a splendid Persian rug. Behind him is a harpsichord. However, this instrument makes us reconsider the portrait for the lid bears the inscription sic transit gloria mundi, that is "All glory is transitory." It is quite possible that this work is not just a portrait of a handsome person but also an allegory for the impermanence of most of life's beautiful things: youth, wealth, and sad to say even music. That the artist would include a bass viol as the focal point of the attention of the subject, whether real or imaginary, nevertheless shows us Netscher's high opinion of the instrument.

These are only two samples of the many portraits of solo violists in the RIdIM collection. In almost every other picture of both soloists and ensembles the instrument is shown in refined surroundings. These portraits add significantly to our awareness of the role of the viol in the musical life of the European upper classes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Continued exploration of musical iconography containing images of viols should help fill some of the remaining gaps in our knowledge of this magnificent instrument during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

1For a more complete explanation of RIdIM, see Barry S. Brook and Carol J. Oja, "The RCMI, RIdIM, and the Exhibition of Eighteenth-Century Musical Ensembles," SYMPOSIUM 18, No. 2 (Fall 1978), 196-203.

2The catalogue of the exhibit may be obtained through the New York office, The Research Center for Musical Iconography, Graduate Center, Room 1010, 33 West 42nd St., New York, NY 10036.

3Research dealing with certain facets of viol iconography has produced several valuable works in recent years. For example, see Ivan Woodfield, The Origins of the Viol (Ph.D. thesis, King's College, University of London, 1977); Richard Leppert, "Viols in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Paintings: The Iconography of Music Indoors and Out," Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America XV (1978), 5-40; and Mary Cyr, "The Viol in Baroque Paintings and Drawings," Ibid., XI (1974), 5-9.

4Richard Leppert, "Concert in a House: Musical Iconography and Musical Thought," Early Music VII, No. 1 (January 1979), 3.

5Leppert, "Viols in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Paintings," 6.

6The remainder are depictions of still lifes, photos of Baroque instruments, facsimiles of pages from treatises and collections of music, etc.

7There are two other treble-size viols being played in ensemble portraits, one by a woman and the other by a child.

8Mus. Versailles Inv. MV 3800. Also see Plates 27 and 38 in the RIdIM exhibit.

9Pierre de Nolhac, Nattier: Peintre de la Cour de Louis XV (Paris: Goupil, 1910), pp. 147-49.

10Cracow, Château de Wawal. See also Plate 32 in the RIdIM exhibit.

11Pieter Fischer, Music in Paintings of the Low Countries in the 16th and 17th Centuries (Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger, 1975), p. 72.