Keyboard harmony is probably the most frustrating course taken by the college music major. For the beginning pianist the initial difficulty of applying theoretical concepts through the use of an unfamiliar instrument is understandable. The piano major, however, is many times equally frustrated because his use of the instrument is often restricted to reiteration of pencil-and-paper chorale exercises.

In all subject areas categorized under "keyboard harmony," neither the capabilities nor the performance problems of the keyboard itself are sufficiently acknowledged. In fact this course is often taught as though it were a class piano course offered in the eighteenth century by twentieth-century non-pianists without an understanding of eighteenth-century performance practice.

First it must be recognized that not only theoretical concepts but also performance skills are involved in the study of keyboard harmony. Students are often enrolled simultaneously in both keyboard harmony and class piano and while there is a close relationship between these two courses—despite their differences in focus—much keyboard harmony instruction ignores and in some cases contradicts the methods used successfully in piano classes.

One of the biggest problems for the author of a keyboard harmony text is to correlate the theoretical aspects of the course with appropriate keyboard performance. Many otherwise carefully-planned and well-written theory texts include keyboard harmony exercises which are simply not appropriate for the average level of keyboard proficiency among first-year theory students.

HARMONIC PROGRESSION

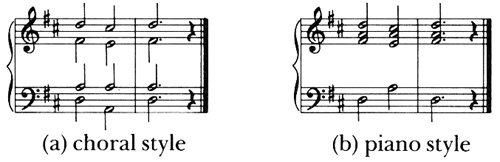

Most keyboard harmony texts distinguish between what is called "choral" style and "piano" style. Duckworth and Brown state, for example, that

writing chords in the choral style . . . has the advantage of making individual voices easier to distinguish. In playing such examples on a keyboard instrument, however, soprano, alto and tenor voices should be taken with the right hand, bass voices with the left.1

One must question why it is not important to "make individual voices easier to distinguish" in keyboard performance as it is in writing notation. Pianists agree that individual voices are easier to distinguish when only two pitches are played in one hand. Consequently even though most keyboard harmony texts disagree, for the purpose of bringing out individual voices choral style is more "pianistic" than piano style. (See Ex. 1)

Ex. 1. Choral Style vs. Piano Style

Neither style uses the keyboard advantageously because the performer is restricted to close position in the middle register. While it has been stated that "chord progressions are handled in four-part close style . . . since facility in open style harmony with correct doubling and voice leading is beyond the capability of the ordinary student,"2 the keyboard itself must be taken into account. Instead of being used as a substitute for four voices, it must be recognized that some of the keyboard's greatest assets in developing theoretical concepts lie in the immediacy of textural change and the range of the instrument versus that of the voice. Therefore while close position is desirable in many instances, the sounds are more coherent when divided equally between the hands and furthermore such pianistic devices as arpeggios, broken chords, and so forth can be played throughout the keyboard to provide a fuller range of harmonic sonorities.

What happens if the pianist is restricted to "piano" style is that each progression becomes a memorized finger-movement pattern (particularly when transposing progressions to different keys). The actual sound and function of each voice in the chord is obliterated by such thoughts as "moving the 3rd R.H. finger up a whole step while the 5th finger moves up a half step," etc. The reality of this can easily be checked by asking a student to use one of these progressions to harmonize a melody. Often he will not be able to choose the appropriate progressions of all, but if he does, will be unable to play the melody at the same time as the progression (in many cases) because of the necessity of changing the chord structure (finger-movement pattern) to the left hand. At any rate the performance will usually be musically lifeless and boring to both the student and to his instructor.

MELODIC HARMONIZATION

As stated above, the rigidity of piano style in playing chord progressions often carries over into the harmonization of melodies. Allen Forte for example acknowledges the practical keyboard approach when he discusses the procedures for composing a soprano voice over a chord progression. He states that "notes above the bass may be played by the left hand while the right hand plays the soprano alone—a more convenient arrangement for the keyboard."3 However, most examples throughout the book are notated in the traditional "three pitches in the R.H. and one pitch in the L.H." manner common to most texts.

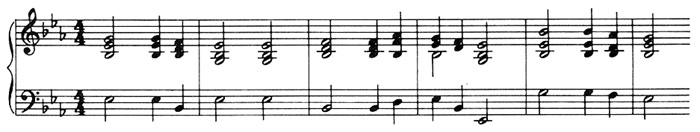

In another example Brings, Burkhart, et al. state that "melodies which move predominately by step but which are also in moderate tempos readily lend themselves to harmonization in which both melody and accompaniment are played together."4 Two examples follow: Go Tell Aunt Rhody and America. Both are written in piano style with the melody in the top voice as shown in Example 2. While several accompaniment patterns precede these examples, this is the first introduction of both melody and harmony played simultaneously.

Ex. 2. Go Tell Aunt Rhody (Excerpt from A New Approach to Keyboard Harmony, p. 42)

Several observations can be made about this example. While there is a consistency of approach from playing chord progressions to the addition of a melodic line (piano style is kept intact), the authors acknowledge the limitations of this method by stating that the melodies should move mostly by step and not at a very fast tempo. While (as the authors continue) "melodies . . . such as America are particularly suited to this style of harmonization,"5 many other melodies will be out of character when performed in this way. Thus the application of piano style is limited to relatively few performance situations.

When indeed this style of harmonization is appropriate to a specific melody, the necessity of playing the soprano melody louder than the surrounding pitches presents a problem to most students, even when the R.H. plays the melodic line only (with the rest of the chord in the L.H.). However, when three pitches are played in the R.H. the melody is almost ways "unheard."

Furthermore in most chordal passages the pianist uses the pedal to enrich the sonority. This arrangement of Go Tell Aunt Rhody also suggests the use of the pedal to connect one chord to another. Since correct pedal usage requires no little amount of skill, the beginning and intermediate pianist usually will omit the pedal entirely resulting in a performance of a series of disconnected chords (hopefully in tempo) without the presence of an audible melodic line.

While these authors correctly state that "the true purpose of studying keyboard harmony is to train the mind and the ear, not the fingers,"6 it seems reasonable to expect a musical sound from the students at all times. This requires a respect for the technical difficulties of the keyboard and consequently the presentation of materials in a way in which these difficulties are reflected.

Melcher and Warch have a much more reasonable approach when they provide three levels upon which students may prepare their melodic harmonizations:

A. For the beginning pianist the accompaniments to be played in the two hands while the melody is played by another student either at a second piano or at the same piano one or two octaves higher than printed.

B. For the intermediate pianist the accompaniments to be played in a simple style by the left hand while the melody is played by the right hand.

C. For the fluent pianist the accompaniments and styles may be as elaborate as the student can manage.7

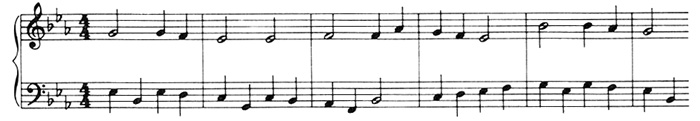

While most keyboard harmony instructors rely on four-part chordal texture to present harmonization possibilities, historically contrapuntal techniques have also been consistently explored. Although most of today's theory texts include references to contrapuntal procedures, students seldom get a chance to develop these concepts at the keyboard. An improvised four-voice fugue would certainly be an unrealistic expectation from a freshman student but the performance of a single line under a given melody is within reach for even the beginning pianist. This procedure in fact can become very important for developing voice-leading concepts in four-part writing. Not only do the chords' functions have to be well recognized but the use of inversions, structural melodic tones, development of harmonic rhythm concepts and even substitute chords can be gleaned from this type of activity. Furthermore the technical demands are minimal. (See Ex. 3)

Ex. 3. Go Tell Aunt Rhody with added melody

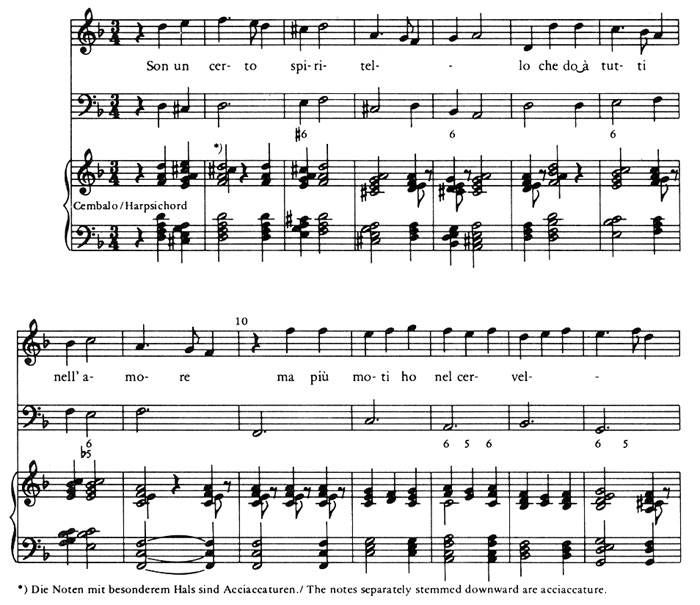

Well-known melodies such as those mentioned above are often harmonized without any given harmonic symbols. When a symbol is presented it usually is a Roman numeral or a figured bass line, both extremely valuable for the keyboard harmony student. However, the poverty of imagination which occurs in other areas of keyboard harmony probably receives its greatest impetus from figured bass realization. Why this lack of creativity occurs is unclear but perhaps it stems from a mistaken idea of traditional eighteenth-century performance practice. During the Baroque period, according to Ferand,

the extemporized realization of a thorough bass accompaniment, and also of purely instrumental sections of vocal compositions (ritornels and the like) could be done in very different ways, resulting in quite considerable differences in sound, depending upon the type of figuration employed, the fullness or thinness of the chords, the number of parts, the strictness or freedom of the setting, the embellishing of the individual parts with ornaments or diminutions.8

Thus the eighteenth-century player varied the texture within his accompaniments and it may be assumed did not restrict himself to one kind of playing.

In Example 4 the progression is made clear through the given soprano, bass, and figures.

Ex. 4. Arietta with Realized Continuo by Anonymous (Excerpt from Improvisation in Nine centuries of Western Music by Ernest T. Ferand, p. 113)

The performer does not necessarily keep the given pitches as his outlying notes. Nor does he limit himself to a four-voice framework. Instead the texture varies from four to nine voices which in many instances results in the repetition of the entire chord in the other hand. The freedom with which he interprets the progression is indicative of the keyboard approach to chordal style in the Baroque period. Why is it not the same today?

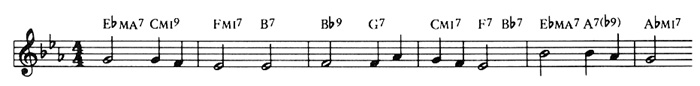

Thoroughbass accompaniment is not the only symbology system which should be incorporated in a keyboard harmony course. The student needs the experience of reading chord symbols over a soprano melody. Not only is this a very practical system but also requires the student to provide his own bass lines—necessitating appropriate choices of chord inversions—a concept certainly as important as providing alto and tenor voices. Furthermore this method enables more complex harmonies to become part of the student's vocabulary. The excerpt of Go Tell Aunt Rhody in Example 5 for instance can easily be played by first-year keyboard harmony students.

Ex. 5. Go Tell Aunt Rhody (Excerpt Using Chord Symbols)

The experience of using chord symbols often occurs before the student enters college. Many students become familiar with these symbols by accompanying melodies with autoharp in elementary school. Instead of this system being expanded as the student becomes a music major, however, it is almost entirely ignored. Benward's theory text is one notable exception in which figured bass and chord symbols are introduced side by side. Benward states that "figured bass was to the eighteenth century what popular music symbols are to the twentieth century—a short-cut notational system involving a modicum of improvisation."9 The keyboard harmony student should be expected to utilize this very functional twentieth-century technique of melodic harmonization.

To summarize, in taking issue with certain authoritative texts the writer suggests that a more accessible means of developing the ability to harmonize melodies has as its basis the performance practice of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Furthermore the symbology which is traditionally used (Roman numerals and figured bass) should be enlarged to include chord symbols to become more compatible with contemporary performance situations.

In conclusion, there are as many ways to harmonize a melody as there are kinds of melodies to harmonize. The student should be encouraged to provide the kind of harmonization which is musical in every sense, no matter whether he is a "new" pianist or a player of many years experience. He should be able to use from two to ten voices, in either contrapuntal or homophonic textures as did the performers of the Baroque period and as do the professional performers of today.

IMPROVISATION

Improvisation is an especially valuable tool in the keyboard harmony classroom since it ultimately defines whether or not a particular theoretical concept has been learned. Many instructors seem to back away from using improvisation because it was never part of their own curriculum. At the same time, more and more students come to class with prior improvisatory experience.

Throughout history improvisation has played such an important role in the development of musicianship that the best musicians were the best improvisers. According to Ferand, "Lorenz Mizler (1738) reports about J.S. Bach that he accompanies a solo with such a thoroughbass it sounds like a concerto and he plays the melody with his right hand as though it had previously been composed that way."10 Yet today most college curriculums limit the development of improvisatory skills to the jazz studies program.

It is true that keyboard harmony courses presently require the student to play notes which are not written down, but much of the time those non-written pitches depend on formula voicings which are simply memorized before the class performance. If the student were allowed to explore the keyboard in a freer way, the musical result would in almost all cases become more interesting—a motivation for the student to develop his understanding of how music works.

1William Duckworth and Edward Brown, Theoretical Foundations of Music (Wadsworth, 1978), p. 102.

2Maurice Lieberman, Keyboard Harmony and Improvisation, Vol. 1 (W.W. Norton, 1957), p. xi.

3Allen Forte, Tonal Harmony In Concept And Practice, 3rd ed. (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979), p. 251.

4Allen Brings, Charles Burkhart, Roger Kamien, Leo Kraft, and Dora Pershing, A New Approach to Keyboard Harmony (W.W. Norton, 1979), p. 42.

5Ibid.

6Idem., p. vii.

7Robert Melcher and Willard Warch, Music For Keyboard Harmony (Prentice Hall, 1966), Introduction.

8Ernest T. Ferand, Improvisation in Nine Centuries of Western Music (Arno Volk Verlag, 1961), p. 18.

9Bruce Benward, Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. 1 (W.C. Brown, 1977), p. 77.

10Ferand, op. cit., p. 19.