A form which was unique when it appeared, and has remained unique ever since.1

Commentators have long noted the finale of the Eroica Symphony as having a structure both unique and unprecedented. Yet no one has presumed to suggest that the structure of this landmark composition might have been, consciously or unconsciously, the result of Beethoven's inspection of a work by another composer. Given this circumstance, the connection proposed in this article, based on musical analysis and letters of Beethoven, should stand as a distinct possibility.

Based upon a theme Beethoven used in three previous works,2 the finale makes a distinct break from the traditional approach to variation procedure, an approach in which each statement of a theme becomes a discrete section in its own right, each elaborated ornamentally, harmonically, rhythmically, texturally. Already in the Opera 34 and 35 piano variations Beethoven had made certain departures from the usual procedures, as he himself acknowledged in his letter of October 18, 1802 to the publishers Breitkopf and Härtel, "I have composed two sets of variations, one consisting of eight variations and the other of thirty. Both sets are worked out in quite a new manner, and each in a separate and different way [Beethoven's underscore].3 In Opus 34 the theme of his own invention reappears successively in keys a third apart. And in Opus 35 the departure from tradition is even more evident; here, the opening tune presented in four initial statements (which Beethoven designates "Introduzione col Basso del Tema") becomes the bass to the main theme for the variations, the whole set being climaxed by a massive fugue which uses as its subject the tune of the introduzione. Concerning the Opus 35, Beethoven wrote to Breitkopf and Härtel on April 8, 1803:

As to the variations, about which you think that there are not as many as I stated, you are certainly mistaken; my difficulty was that they could not be indicated in the same way; for instance, in the grand ones where the variations are merged in the Adagio, and the Fugue, of course, cannot be described as a variation; and similarly the introduction to these grand variations which, as you yourself have already seen, begins with the bass of the theme and eventually develops into two, three and four parts; and not till then does the theme appear, which again cannot be called a variation, and so forth.4

The inspiration to invert the subject midway through the keyboard fugue may have come from the D-sharp Minor fugue of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, No. 8, one of two fugues in the collection having the same tonic (although the minor mode) as the symphony. Perhaps coincidentally, both subjects begin with a tonic-dominant ascent. It is also possible that the seeds for this technique may have been implanted in Beethoven's mind during his early years in Vienna, at a time when he conceivably became acquainted with Bach's English and French Suites, in which the second half of the gigues frequently begin with the inverted subject set in a quasi-fugal texture.5

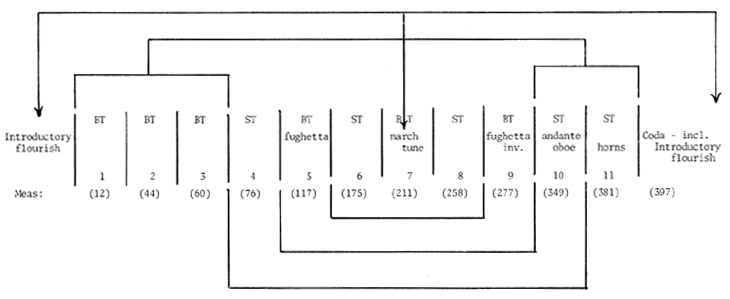

In the Eroica finale Beethoven shows a completely new way of arranging the melodic material he had employed in the three previous works. In substantially reducing the number of sections from 33 of the piano set (including those in the introduzione, as well as the fugue and two closing variations) to 11 (plus coda) in the finale, the movement assumes a "symphonic" thrust which brings the whole symphony to a conclusion. The momentum of the finale is controlled, so to speak, by its symmetrical plan which encompasses elements of rondo, fugue, and a variety of modulatory shifts (perhaps generated by the example of Opus 34). Symmetry is achieved primarily in four ways (see Figure 1):

| Figure 1. Finale, Eroica Symphony | (BT = bass theme; ST = soprano theme) |

(1) The seventh section, in G minor (the only one having the "march" tune), is assigned a central position, around which other sections are arranged. The three central sections (6, 7, 8) themselves are framed by the only fugues in the movement (sections 5, 9), the second of the fugues having the subject (the "bass" tune) inverted, as in the second half of the fugue in the Opus 35 piano variations.

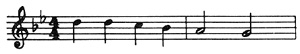

(2) The "march" melody itself is derived from the introductory flourish (or vice versa?) which recurs, transposed, near the end. Thus, for the tune in section seven, the pitches of the introductory flourish (starting with the same initial high D) are converted into the martial, dotted-eighth rhythm (see Ex. la and b).

Ex. 1a. Introductory flourish

Ex. 1b. March tune

At this pivotal point in the movement the G Minor tonality alluded to at the very beginning is incontrovertibly confirmed. With respect to the history of the "march" tune, Alexander L. Ringer has suggested its derivation from the principal theme of the Sonata in G Minor, Opus 7, No.3, by Muzio Clementi.6

(3) The emphasis on the "bass" tune in the first three sections is replaced by emphasis on the "soprano" tune in the final two variations (andante) prior to the coda.

(4) The alternation of the "bass" and the "soprano" tunes results in a rondo-like procedure which involves sections four through nine.

During the years 1800-03, when Beethoven was producing the Eroica and other compositions using the Prometheus theme, he frequently mentioned J.S. Bach in his letters. One of Beethoven's early testimonials to Bach's greatness appears in his letter to the music publisher, Franz Anton Hoffmeister (January 15 or thereabouts, 1801):

Your desire to publish the works of Sebastian Bach [Beethoven's underscore] is something that really warms my heart which beats sincerely for the sublime and magnificent art of that first father of harmony [Urvater der Harmonie]. I trust that I shall soon see this plan fully launched and I hope that as soon as we hear the announcement of our golden age of peace I myself shall be able even from Vienna to contribute something to this scheme when you are collecting subscriptions for it.7

In another letter (to Breitkopf and Härtel, April 22, 1801) Beethoven expresses his concern for the destitute condition of the master's only surviving daughter, Regina Susanna (1742-1809):

I recently visited a good friend of mine who mentioned the sum that had been collected for the daughter of the immortal god of harmony, and I was amazed at the small amount which Germany, and especially your Germany, had contributed to this person whom I revere for the sake of her father. And that has made me hit on the following idea; how would it be if I were to publish some work by subscription for the benefit of this person and, in order to protect myself against all attacks, to inform the public of the sum collected and of the yearly profit from the work?—You could do most for this object. Let me know quickly how it could best be arranged, so that it may be done before this brook dies or, rather, before this brook has dried up and we can no longer supply it with water—It is clearly understood, of course, that you would publish the work.8

More than two years later (during the time he was composing the symphony) in a letter discussing mistakes in the August 1803 publication of Opera 34 and 35, Beethoven once again brings up the matter of Regina Susanna: "I shall do something for Mlle Bach as soon as the winter begins. At the moment there are too few influential people in Vienna and without these I could not collect an appreciable sum."9 And finally in the letter of April 18, 1805 Beethoven proposed a benefit concert at which the Christus am Ölberge, Opus 85 (1802), and the Eroica Symphony would be performed: ". . . the two works fill up an evening quite nicely—if there is no other arrangement to upset this, then my resolve and my desire are that the profits should be given to Madame Bach, to whose relief I have long been intending to make some contribution."10 Whether consciously or unconsciously, his choice of the Eroica may have been dictated by a desire to express indirectly through the daughter his gratitude for the role her father's music had played in the composition of the symphony almost two years previously.

To be sure, Ringer has posed melodic relationships between the Eroica finale and the Clementi Piano Sonata in G Minor, Opus 7, No. 3. Yet this work by the English musician "contributed but little to a better understanding of the Eroica's structure."11 In light of the absence of any suggestion in Beethoven scholarship that a work by another composer might have served as a structural model for the Eroica finale, the following remark in the letter (see footnote 4) concerned with the uniqueness of the Opus 35 piano variations looms as a possible clue: "Thank you very much for the fine works of Sebastian Bach. I will treasure and study them" [Beethoven's underscore].12 Dated April 8, 1803 this letter was written after Opus 35 had been completed and just one month before the symphony was begun. In his thematic catalogue of Beethoven's works, Georg Kinsky lists Opus 35 as having been written in 1802 (on the title page, not in Beethoven's hand, is inscribed, "Variations 1802"). The work was published by Breitkopf and Härtel, August 1803. The Third Symphony Kinsky lists as having been composed May through October 1803, completed the beginning of 1804, and published by the Kunst- und Industrie-kontor (Vienna), October 1806.13 At this time, just before and during the composition of the Eroica, very little of Bach's music had been published with the exception of the motets,14 making it a strong likelihood that these were the works Beethoven had been sent. Anton Schindler has confirmed that "a few motets" were among the small number of works by Bach which Beethoven owned.15 Beethoven's previous encounters with the music of Bach seem to have been limited to his distinguished performances of the Well-Tempered Clavier during his early years in Vienna and to the music he probably saw at the house of Baron van Swieten. By 1792 the only works of Bach to be printed were the four parts of the Clavierübung, the Kunst der Fuge, the Musicalisches Opfer, some organ chorale preludes, possibly some of the inventions, and some minor works. By the year of Beethoven's death the list had not increased appreciably. Baron van Swieten's collection, which Beethoven presumably came to know during his early years in Vienna, consisted of manuscript copies of the six English and six French suites, probably the Italian Concerto and the Violin Sonata in A Minor.16 There is thus no reason to doubt that Beethoven meant seriously his declaration to "treasure and study" whatever music he could acquire by the Baroque master. Of the motets, it is Jesu, meine Freude that appears to have striking structural similarities with the finale of the symphony. Even the text, with its emphasis on the triumph of the spirit over sin and death, may have drawn Beethoven to this motet over the others, for its message is consistent with the composer's concerns during this time following the Heiligenstadt turmoil and during the time of his involvement with the Prometheus music. Certainly, as Ringer has observed, "the complexity of Beethoven's mental associations" is a factor which must be considered if one is to untangle the diverse threads that feed into his creative process.17

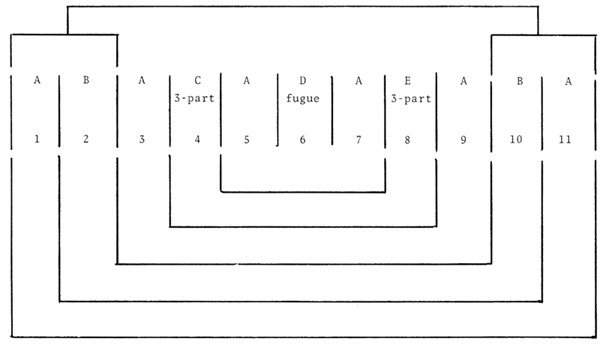

With reference to Figures 1 and 2, it is clear that both compositions manifest an arch shape, with close structural correspondences.

Figure 2. Motet, Jesu, Meine Freude

Both, in eleven movements/sections, have a central, axial section (the fugue movement in the motet, the "march" section in the symphony) around which the other movements/sections are symmetrically arranged. In both, the central three movements/sections are framed by music not found elsewhere in each work, in the motet the movements (4, 8) being the only three-part settings, in the symphony the sections (5, 9) being the only fugues. In both, the symmetrical layout is enhanced by a reversal process with respect to the last two movements/sections in relation to the first two/three, in the motet the ordering of the last two movements (10, 11) reversed from the first two (two and ten having nearly identical music), and in the symphony the appearance of only the "soprano" tune in the final two sections (10, 11) as a reversal of the emphasis on the "bass" tune in the first three sections. Further tightening of the structure in the symphony is evident in the reappearance of the introductory flourish in the coda and its transformation ("march" tune) in the middle. In addition to these symmetrical affinities, in both works the alternation of movements/sections is clear—in the motet the alternation of the chorale tune (odd-numbered movements), and in the symphony the alternation of the "bass" with the "soprano" tune (sections 4 through 9). Lastly, the note-against-note setting in several of the chorale movements in the motet corresponds to this setting of the "soprano" tune in the final two sections of the symphony, especially section ten, resulting in the meditative hymnal quality discernible in much of the composer's subsequent music, including the last movement of the Waldstein Sonata, the violin concerto, the slow movement of the Ninth Symphony, portions of the last piano sonatas and string quartets.

Considered collectively, all these features argue in favor of the possibility that Beethoven's inspection of Jesu, meine Freude suggested to him new procedures for organizing melodic material he had used in previous compositions. To be sure, the dissimilarities between the two works are self-evident. The motet consists of separate movements which have definite endings, while the finale consists of a single movement containing a series of relatively brief, interconnecting sections. Certainly, each composer is working within his own personal, stylistic, and historical modus operandi. And admittedly, various rondos and sonata rondos of the classical period reveal elements of symmetry. Even so the chronological considerations presented in this article, along with the number and type of structural correspondences existing between the two works, employing Baroque procedures, suggest strongly that the possibility of influence, whether consciously or unconsciously inspired, cannot be overlooked.

In contrast to structural affinities, thematic relationships between the two works are tenuous, even though a similarity exists between the "march" melody in section seven of the symphony (especially clear in the sketches as transcribed by Nottebohm)18 and the chorale tune of the motet (Ex. 2a, b).

Ex. 2a. Chorale tune, first phrase (transposed from E minor)

Ex. 2b. March tune sketch

Both tunes, in minor, start on the dominant scale degree, both prolong by repetition the initial pitch, and both descend to the tonic with an emphasis on the supertonic (an agogic accent in the motet, an échappée in the symphony). This is as close as Beethoven comes to any sort of thematic quotation from the motet. While Alexander L. Ringer has suggested that the "march" tune was derived from the principal theme of the Clementi Piano Sonata in G Minor (see footnote 6), this does not in itself invalidate the alternative that there may have been multiple influences on Beethoven, including the chorale tune—composed around 1653 by Joann Crüger (1598-1663)—all of which played their respective roles in his shaping the final version of the theme.

Scholars have concurred that the increasing prominence of counterpoint in Beethoven's "third period" is attributable partly to the influence of Bach. But it is from the perspective of "solid and logical structure" that Karl Geiringer has discussed the Diabelli Variations in connection with "the strong concern for the idiom of the Baroque that Beethoven displayed in his last works." Accordingly, Geiringer concluded, "thus we recognize a strictly symmetrical organization in the Diabelli Variations such as the Bach period loved to employ."19 The existence of this same sort of mirror symmetry in the Eroica finale, however less involved, suggests an adjustment in our thinking concerning the period in which Bach's music had influence on Beethoven's compositions. The influence may have come in the early months of 1803 when a copy of the motets reached his desk in time to aid him very practically in his search for new ways of structuring previously-used material. The result represented Beethoven's highly personal adaptation of an architectural model from the Baroque.

1Donald Francis Tovey, Essays in Musical Analysis, Vol. 1 (Symphonies) (London: Oxford University Press, 1935), p. 32.

2Contredanse for orchestra, No. 7 of 12, WoO 8 (1800); Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus, Opus 43 (1800); the Piano Variations, Opus 35 (1802); the Eroica Symphony finale, Opus 55 (1803).

3Emily Anderson, The Letters of Beethoven, 3 vols. (London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd., 1961), I, 76.

4Idem, pp. 88-89.

5Donald MacArdle, "Beethoven and the Bach Family," Music and Letters XXXVIII, No. 4 (October, 1957), 354.

6Alexander L. Ringer, "Clementi and the Eroica," Musical Quarterly XLVII, No. 4 (October, 1961), 454-68.

7Anderson, op. cit., I, 47. On April 22, 1801, Beethoven wrote to Hoffmeister, "Enter my name as a subscriber to the works of Johann Sebastian Bach." (Idem, p. 51.)

8Idem, I, 53-54. Since Bach's name in German also means brook, this is assuredly an example of Beethoven's delight in the use of puns.

9Idem, I, 96; letter to Breitkopf and Härtel, September, 1803.

10Idem, I, 133; letter to Breitkopf and Härtel.

11Ringer, op. cit., p. 46.

12Anderson, op. cit., I, 89; letter to Breitkopf and Härtel. Following his reference to Bach in this letter, Beethoven writes, "If you have a fine text for a cantata or any other vocal work, do let me see it." From this, it would appear most likely that Beethoven received choral works by Bach.

13Georg Kinsky, Das Werk Beethovens. Thematisch-Bibliographisches Verzeichnis seiner sämtlichen vollendenten Kompositionen (Munich: G. Henle, 1955), p. 87.

14Konrad Ameln, Johann Sebastian Bach. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Serie III, Band I. Motetten. Kritischer Bericht (Basel and Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1967), p. 75, after printing the title page of the first edition, second part (which included Komm, Jesu, komm; Jesu, meine Freude; and Der Geist hilft unsrer Schwachheit auf), gives 1803 as the publication date. (The first part, including Singet dem Herrn, Fürchte dich nicht, and Ich lasse dich nicht, this last by Johann Christoph Bach, a misattribution perpetuated through 1949 by the Peters Corporation, was published by Breitkopf and Härtel in 1802.) The 1803 date also appears in Wolfgang Schmieder, Thematisch-Systematiches Verzeichnis der Musikalischen Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach (Wiesbaden: Breitkopf and Härtel, 1966), p. 305. In providing the publication date, Donald MacArdle ("Beethoven and the Bach Family," p. 354) reveals the source of his information as being Schmidt and Knickenbert, Das Beethoven-Haus in Bonn und seine Sammlungen (Bonn: Verlag des Beethoven-Hauses, 1927). Karl Geiringer (Johann Sebastian Bach, New York: Oxford University Press, 1966, p. 182) and Emily Anderson (op. cit., I, 89, fn. 6) likewise agree with the publication date.

15Anton Felix Schindler, Beethoven as I Knew Him, ed. by Donald W. MacArdle, trans. by Constance S. Jolly (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1972), p. 380. According to Schindler, "Beethoven's library contained very little by that patriarch of music Johann Sebastian Bach. Apart from a few motets, most of which had been sung at van Swieten's soirées, he had most of the music of Bach known at that time: the Well-tempered Clavier, which showed signs of diligent study, three volumes of the Clavierübung, 15 two-part inventions, 15 three-part inventions, and a toccata in D Minor. This total collection in a single volume is in my keeping."

16For more on this topic, see MacArdle "Beethoven and the Bach Family," op. cit., pp. 353-58.

17Ringer, op. cit., p. 460.

18Gustav Nottebohm, Ein Skizzenbuch von Beethoven aus dem Jahre 1803 (Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1880), p. 51.

19Karl Geiringer, "The Structure of Beethoven's Diabelli Variations," Musical Quarterly L, No. 4 (October, 1964), 502.