In a consideration of Handel's oratorios, neither a purely musical nor a purely dramatic approach is sufficient; dramatic and musical structures are interdependent. Although no large-scale, systematic, analytical studies have been made which consider the structural combination of drama and music in Handel's oratorios, those acquainted with them agree that, even though they last several hours, somehow both elements are bound together into a comprehensible structure, an artistic, organic whole. The question remains, How are they bound together? What system of coherence, if any, is at work?

Admittedly, the mystical vision granted the artist often defies analysis. Articulating the system of coherence that binds a Handel oratorio into an organic whole poses the same difficulties as articulating the system that binds the four movements of a Mozart symphony or the acts of a Shakespeare play. It is only through extensive contact with the musical score, repeated reading of the libretto as literature, and repetition of the listening experience that Handel's order, symmetry, and expression reveal themselves.

Northrop Frye's approach to literary criticism asks the critic to assume that the work of literature being examined is unified:

The primary understanding of any work of literature has to be based on an assumption of its unity. However mistaken such an assumption may eventually prove to be, nothing can be done unless we start with it as a heuristic principle. Further, every effort should be directed toward understanding the whole of what we read, as though it were all on the same level of achievement. We should hold to this conception as long as possible, in defiance of everything our taste tells us, even if the work we are studying is obviously uneven in achievement. The critic may meet something that puzzles him, like, say, Mercutio's speech on Queen Mab in Romeo and Juliet, and feel that it does not fit. This means either that Shakespeare was a slapdash dramatist or that the critic's conception of the play is inadequate. The odds in favor of the latter conclusion are overwhelming: consequently he would do well to try to arrive at some understanding of the relevance of the puzzling [or dull] episode. Even if the best he can do for the time being is a far-fetched or obviously rationalized explanation, that is still his sanest and soundest procedure.1

This approach is equally useful when dealing with music, for we are assuming that artistic unity exists in Handel's oratorios. Therefore, if after listening to a Handel oratorio, a number or segment seems dull, puzzling, or out of place, Frye's approach should be applied. By explaining how each number fits into the overall dramatic and musical structure, even if the explanation is "far-fetched or obviously rationalized," the critic may achieve some understanding of these puzzling passages.

Any analysis of Handel's oratorios on the larger structural level depends on and must be preceded by the listening experience; it is difficult to make observations based only on an examination of the musical score. What is essentially at issue is the critic's response to the musical and dramatic score, how he perceives Handel's dramatic shape, pacing, and direction; he could respond more easily if he does not have to imagine how the music sounds while conjuring up three-dimensional scenes and characters.

The student of literature faces the same problem: a play or a poem comes alive only when it is sounded and inflected through the act of presentation. Bernard Beckerman states that drama or theater occurs only "when one or more human beings isolated in time and space present themselves in imagined acts to another or others."2 The act of presentation, whether live or recorded, is the basis for the theatrical and listening experience.3

Because Handel still remains buried under two hundred years of a tradition which has regarded him as a composer of "religious" music, we fail to recognize or accept that he was first and always a dramatist, a composer of theatrical entertainment. While analysis of musical elements in these works is valuable, musicians have lost sight of the fact that Handelian oratorio is drama. We have yet to get Handel out of the choir loft and onto the stage. Even if we agree that Handel is a dramatist whose bailiwick is the theater stage, there is little grasp of his dramatic practice in general. Students in a music curriculum examine many dramatic compositions but are rarely taught the tools of dramatic theory to enable them to approach the works as theater as well as music.

In this study, first the libretto is divided into its dramatic units or segments, and then the musical material is related to these segmented wholes. A segment or unit is a coherent section of the drama or theatrical time that nests within a formal dramatic unit such as a scene or act. It has a beginning, middle, and end; a rhythmic pulsation of intensification and decrescence; or a rise and fall of tension. The segments may be long or short, simple or complex, employ the entire cast or one character. Segments may coincide with scenes, but scene divisions in eighteenth-century librettos usually are merely indications of the entering or exiting of characters. No set formulae determine what portion of an act composes a coherent unit. Segmental coherence can be determined only through a study of the entire structure. Generally speaking, at least for Handel's librettos, a segment is a unit of time in a given locale. This time is spent by the characters in performing certain activities. The playing time or stage time consumed in performing these activities may be equal to real or actual time. For instance, if a character is eating part of a meal on stage, the stage time elapsed will be the same as actual or real time elapsed. However, the dramatist or composer may wish to manipulate time and telescope or condense a given activity depending on the dramatic effect desired. In these cases, the audience imagines that a certain span of time has passed even though it does not equal actual time elapsed. For instance, several actors running across stage waving flags may represent a battle which lasted several days. (Handel used orchestral interludes to indicate the passage of time. Since the oratorios were not staged, the insertion of these interludes was a brilliant dramatic device. Perhaps many of Handel's symphonies would never have been written if the works had been staged.) A segmental change should be expected at a shift in time (real or imagined), shift of locale, or shift of the character's focus of attention even though the locale and time remain unchanged.

In this study, the elements of analysis are these segmented units of time, what occurs in each of them, and the way they are linked and related to each other. Each segment works out a thread of the drama. When all segments are combined, the entire dramatic fabric is presented.

In addition to dramatic segments, Handel's design achieves coherence through his use of dramatic rhythms. Dramatic rhythm refers to the alternation of sections which are predominantly active, acted, dynamic, or in motion with sections that are mostly static, inactive, reactive, or stationary. These shifts in pacing sometimes, but not necessarily, parallel or overlap the dramatic segments.

The reader may feel that this approach is slanted toward drama; that in the consideration of text and music, the weight of material is tilted toward the text at the expense of the music. But this is not just an exercise in literary criticism. Bertrand Bronson has suggested that reading the libretto without Handel's music is something analogous to reading a microfilm with the naked eye.4 On the other hand, if we follow a purely musical approach to Handel's works, and imagine a performance with all vocal parts played instrumentally, we find that, without the words, much of the music is meaningless and formless. In a dramatic/musical work, the words and music are inseparable and indivisible. The music illuminates and articulates the dramatic situation. Handel was knowledgeable in English literature; he moved in literary circles and was acquainted with some of the foremost literati of his day. It was his practice to begin composition only when the libretto was in his hands. With the exception of those texts taken verbatim from the Bible (Messiah), Milton (L'Allegro), and Dryden (Alexander's Feast), all the librettos are actable dramas. Therefore, the initial approach to Handel's oratorios is here through the text; and when we understand the manner in which dramatic structures and literary conventions of the period function, the musical details are quickly and easily understood.

Although Handel's musical-dramatic coherence is demonstrable at the higher level of an entire oratorio, an initial examination of a single act will quickly illustrate the complementary relationship of drama and music. The second act of Solomon provided Handel with a superb theatrical scene, and his use of key scheme and tonal structure, or form sequence and manipulation, and of dramatic rhythm articulates the shape of this act.

Act II contains three dramatic segments: static beginning and ending enclose an intense, active middle. In segment A (1-5) of Table 1, the Israelites pray for a long and virtuous reign for Solomon, and he praises the Lord for giving him wisdom.5

TABLE 1

HANDEL, SOLOMON, ACT II: SEQUENCE OF FORM, TONALITY, TEMPO

| "A" ca. 39' |

| 1. | CHORUS | D | Allegro | |

| 2. | rec | |||

| 3. | ARIA (ritornello) | g | Larghetto | |

| 4. | rec | |||

| 5. | ARIA (ritornello) | a | Allegro |

| "B" ca. 26' |

| 6. | rec | |||

| 7. | TRIO | f-sharp | A tempo giusto | |

| 8. | rec | |||

| 9. | ARIA (ritornello) | F | Allegro | |

| 10. | rec | |||

| 11. | ARIA | f | Largo, e piano | |

| 12. | ACCOM |

| "C" ca. 23' |

| 13. | DUET | E | Andante larghetto | |

| 14. | CHORUS | A | Allegro | |

| 15. | rec | |||

| 16. | ARIA (ABA) | F | Allegro | |

| 17. | rec | |||

| 18. | ARIA (ABA) | G | ||

| 19. | CHORUS (ABA) | D | Allegro |

In segment B (6-12), two women appear before the King, both claiming the same baby. Solomon decrees that the baby shall be cut in half to settle the dispute. The false mother applauds the decision while the true mother agrees to give up her child in order that he may be spared. In segment C (13-19), the baby is restored to the true mother, and Solomon is praised for his wisdom.

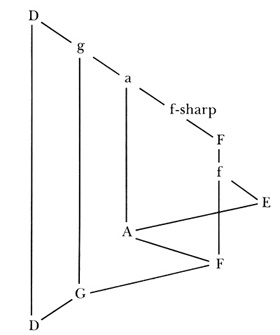

In examining the tonal structure, it is often helpful to look first at the key scheme in the abstract, keeping in mind that conclusions derived from such charts are valid only when related to the dramatic content.

Example 1 presents the sequence of tonalities using white and black notes to stand respectively for major and minor tonalities of the choruses and arias.

Ex. 1. Handel, Solomon, Act II: Sequence of Tonalities

The recitatives are tonally unstable and therefore not included. The act begins and ends with frame choruses in D major, the D tonality being necessary to accommodate the trumpets of the period. The key scheme works its way down to E major; or if you mentally invert the diagram, it works its way up to E major. Assuming the most obvious possibility, we may guess this is the high point or climax of the act. And this is indeed the case. E major is approached through keys which are abstrusely related, reflecting the increase in dramatic tension; and the return to D major is accomplished through keys more closely related to parallel the release of dramatic tension.

This may seem like an over-simplification and of no significance. However, the tonal shape corresponds to the dramatic shape and rhythm of the act. Segment A provides a static introduction to segment B in which the action intensifies and leads to a dramatic climax; segment C releases the tension of B. If we plot the dramatic level of intensity for the act on a graph, we would have an arch. This shaping is obviously necessary if we consider it is not feasible or possible to begin an act at a feverish level of intensity and maintain that level throughout. Static sections of lesser intensity must be written which either throw into sharper relief the highly intensive sections or release and relieve the tension built up during the active segments.

Handel not only let the overall drama affect his tonal shaping and musical pacing; he also let the actions of characters affect his manipulation of musical forms and musical conventions in order to articulate the drama. The normal Baroque procedure placed the action in the recitatives, whereas the arias were reflective. The arias of segment B are all active and propel the dramatic action forward. The two arias of segment A (3, 5) are conventional ritornello arias, and the last two arias and chorus of segment C (16, 18, 19) are conventional da capo forms. But all three arias of segment B (7, 9, 11) show formal irregularities. "Words are weak" (7) begins as a solo and progresses to a trio when the second woman enters to dispute the claim of the first, and Solomon has to referee. Handel sharply portrays three characters at once, each with different music, mood, and style within a single number. After Solomon renders his decision to split the baby, the false mother applauds the decision in music which reflects her flippant manner (9). But her hatred swells, and she begins to lose emotional control. So, for dramatic effect, Handel does not finish the form but truncates the aria without a closing ritornello. (We will see the same device used in Saul, 35). The text in "Can I see" (11) portrays the reaction and emotional conflict of the true mother to Solomon's decree. She resolves to give up her child in order that he may be spared. This dualism of text is articulated by a dichotomy in the music: the aria begins in F minor, Largo e piano, with a weeping figure or dotted notes in the bass, coupled with dissonant suspensions in the violins. At measure 39, the mother's resolution shifts the music without any preparation to the relative major mode, running eighth notes in the bass punctuated by block chords in the upper strings, producing the effect of an Allegro. To reflect the change in mood of the text, Handel uses two Affekte in antithesis within the same aria, keeping them standing apart in a state of equilibrium. The two contrasting motives for these Affekte depend upon and complement each other, but one does not generate the other in a continuous development. It is as though we have two arias in one. Handel uses the same procedure elsewhere: compare "My Father" in Hercules, "No Cruel Father" in Saul, and "Thy Glorious Deeds" in Samson.

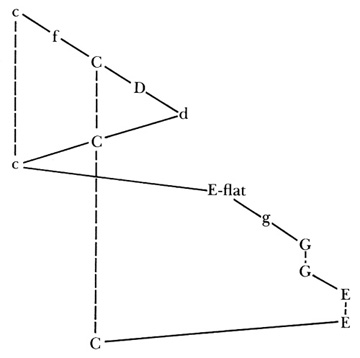

As seen in this act (Table 2), the tonal structure clearly corresponds to the dramatic shape, and Handel's treatment of form parallels the dramatic rhythm: conventional forms are used in static segments, and formal irregularities appear in the active segment.

TABLE 2

HANDEL, SOLOMON, ACT II: TONAL CENTERS/RELATIONSHIPS

In the following examination of Saul, we see that Handel weds his music to the dramatic structure of the entire oratorio, using the same compositional principles seen in the single act from Solomon.

The first act of Saul (Tables 3 and 4) consists of three dramatic segments.

TABLE 3

HANDEL, SAUL: SEQUENCE OF FORM, TONALITY, TEMPO

| Act I |

| "A" ca. 11' |

| 1. | CHORUS | C | A tempo giusto | |

| 2. | ARIA | c | Larghetto | |

| 3. | TRIO | c | Ardito | |

| 4. | CHORUS | G | Larghetto/A tempo ordinario | |

| 5. | CHORUS | C | A tempo giusto |

| "B" ca. 25' |

| 6. | rec | |||

| 7. | ARIA | B-flat | Larghetto | |

| 8. | rec | |||

| 9. | ARIA | F | Larghetto | |

| 10. | rec | |||

| 11. | ARIA | G | Andante | |

| 12. | rec | |||

| 13. | ARIA | A | Allegro/Larghetto | |

| 14. | rec | |||

| 15. | ARIA | b | Largo | |

| 16. | rec | |||

| 17. | ARIA | G | Allegro | |

| 18. | ARIA | a | Moderato | |

| 19. | ARIA | F | Larghetto |

| "C" ca. 37' |

| 20. | SINFONIA | C | Andante allegro | |

| 21. | rec | |||

| 22. | CHORUS | C | Andante allegro | |

| 23. | ACCOM. | |||

| 24. | CHORUS | C | Andante allegro | |

| 25. | ACCOM. | |||

| 26. | ARIA | e | Andante allegro | |

| 27. | rec | |||

| 28. | ARIA | A | Larghetto | |

| 29. | rec | |||

| 30. | ACCOM. | |||

| 31. | rec | |||

| 32. | ARIA | F | Largo | |

| 33. | SINFONIA | F | Largo | |

| 34. | rec | |||

| 35. | ARIA | B-flat | Allegro | |

| 36. | rec | |||

| 37. | ARIA | F | Allegro | |

| 38. | ACCOM. | |||

| 39. | ARIA | b/G | Larghetto/Allegro | |

| 40. | ARIA | d | Larghetto | |

| 41. | CHORUS | g | Allegro |

| Act II |

| "A" ca. 21' |

| 42. | CHORUS | E-flat | Andante larghetto | |

| 43. | rec | |||

| 44. | ARIA | c | Allegro moderato | |

| 45. | rec | |||

| 46. | ARIA | E | Moderato | |

| 47. | rec | |||

| 48. | rec | |||

| 49. | ARIA | F | Largo | |

| 50. | ARIA | F | Andante | |

| 51. | ARIA | F | Largo/Andante | |

| 52. | rec | |||

| 53. | ARIA | G | Allegro | |

| 54. | rec |

| "B" ca. 9' |

| 55. | rec | |||

| 56. | DUET | G | Andante | |

| 57. | CHORUS | G | Andante | |

| 58. | SINFONIA | C/c | Largo/Allegro |

| "C" ca. 4' |

| 59. | rec | |||

| 60. | DUET | g | Allegro ma non troppo | |

| 61. | rec | |||

| 62. | ARIA | E-flat | Allegro |

| "D" ca. 4' |

| 63. | rec | |||

| 64. | ARIA | g | Largo assai |

| "E" ca. 8' |

| 65. | SINFONIA | C | Allegro | |

| 66. | ACCOM. | |||

| 67. | rec | |||

| 68. | CHORUS | D | A tempo giusto/andante larghetto |

| Act III |

| "A" ca. 11' |

| 69. | ACCOM. | c | Largo | |

| 70. | rec | |||

| 71. | rec | |||

| 72. | ARIA | f | Largo | |

| 73. | ACCOM. |

| "B" ca. 4' |

| 74. | SINFONIA | C | Allegro | |

| 75. | rec | |||

| 76. | ARIA | D/d | Allegro/Adagio |

| "C" ca. 32' |

| 77. | MARCH | C | Grave | |

| 78. | CHORUS | c | Largo assai | |

| 79. | ARIA | E-flat | Lento | |

| 80. | ARIA | g | Largo e piano | |

| 81. | ARIA | G | Largo | |

| 82. | CHORUS | G | Allegro | |

| 83. | ARIA | E | A tempo giusto | |

| 84. | SOLO/CHORUS | E | [A tempo giusto] | |

| 85. | rec | |||

| 86. | CHORUS | C | Allegro |

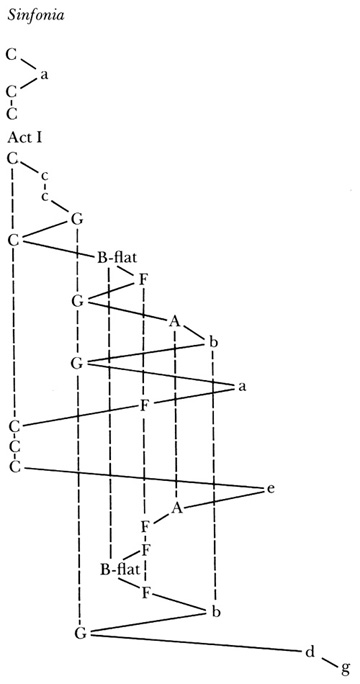

TABLE 4

HANDEL, SAUL, ACT I: PROGRESSION OF TONALITIES

Following the dramaturgy of the period, the act begins at a low level of intensity. Segment A sets the stage by relating past events, and segment B introduces the characters. The dramatic pacing of both segments is regular and even. Segment C reveals Saul's jealousy and his ensuing conflict with David and is therefore more angular in its dramatic rhythm, proceeding in bursts and lulls.

Segment A (1-5)6 is "An Epinicion or Song of Triumph for the Victory over Goliath and the Philistines." It is ceremonial and static, yet the events it relates precipitate reactions in the following segments. Tonally and formally, it is a closed structure. It begins with a chorus in C major. The same material in abbreviated form is repeated at the end of the segment (5) with a Hallelujah chorus added as a coda. Between the opening chorus and the chorus closing this segment are an aria, trio, and chorus in the related keys of C minor and G major. Thus the key scheme of the entire segment is C major, C minor, G major, C major. Tempo indications for the five numbers form a mirror structure (A tempo giusto, Larghetto, Ardito, Larghetto, A tempo giusto). The entire segment may be considered one continuous construction, its character and construction resembling a Chandos Anthem. The flow from number to number is maintained by abbreviating the instrumental closing (1 and 4) or eliminating the instrumental close altogether and eliding the numbers as from 2 to 3, where the closing cadence of 2 is the beginning of 3. Instrumental introductions to 4 and 5 are no more than a single chord.

The characters are introduced in segment B (6-19). They are initially portrayed through a series of reactions to the pronouncements of Saul in 8 and 16. What follows each of these pronouncements is a chain of emotional reactions to the situation. (Saul offers his daughter Merab to David in 8 and informs her of this in 16.) Dramatically, each number emerges from and is a reaction to the previous number. In 9, David thanks Saul for his favor. David's modesty and piety impresses Jonathan who pledges his friendship to David in 10. Merab reveals to Jonathan that she is appalled (11, 12) that a prince would befriend one of such low birth; in 13 Jonathan responds by explaining to her his basis for friendship. The High Priest interrupts this exchange long enough to bless the example of David and Jonathan in 14 and 15. A similar pattern of unfolding begins after the second pronouncement of Saul in 16.

Tonality also helps character portrayal. The first five arias of segment B introduce five characters in five different keys (Michal, B-flat major; David, F major; Merab, G major; Jonathan, A major; and High Priest, B minor). This is not to say that Handel assigns one key to each character to be used every time that character sings. Nor do these keys play a major role in the tonality of each character's appearances. All of these characters utilize other keys later in the oratorio. But within the larger tonal scheme, Handel is using tonality to delineate segment B from segment A. Whereas C major is the tonal parameter for segment A, segment B shifts away from and avoids C major.

The consistent alternation of recitative and aria throughout segment B contributes to the regular and even pacing of the segment. (Numbers 17-19 are a continuous construction equaling one three-part uninterrupted aria.) Nevertheless, the segment still has its own rhythm of intensity and relaxation. The intensity accumulated in numbers 6-13 is dispelled with the High Priest's aria (15). This suspension of action also prepares for Saul's next pronouncement (16). Dramatic tension again builds during the squabble between the two sisters (17-19). The tension is broken off and interrupted by the beginning of segment C when the parade of women appears.

Segment C (20-41) is in marked contrast to segment B. (Segment C will be further divided into sub-sections C1, 20-26; C2, 27-33; and C3, 34-41.) Whereas segment B contains a series of reactions to previous events, the active emphasis of segment C builds intensity and propels us to an inevitable crux. The force comes from the accretion of numbers in a continuous and cumulative sequence of events. This linear movement ebbs and flows, but the dramatic rhythm pointing toward an ultimate crisis is sustained. The acted emphasis of segment C is increased by having characters exiting and entering as opposed to segment B where all characters remain together on stage throughout the segment.

Segment C begins with an unusual instrument (carillon) to accompany a festive parade of villagers, and uses a repetition scheme: numbers 20, 22 and 24 are all in C major and all use the same musical material. The scoring is increased for each return of this material. This scheme generates the feeling that the crowd announced in 21 is approaching, thus enhancing the dramatic effect. Saul's interposed accompanied recitatives (23, 25) break into this scheme. This quick alternation between Saul and chorus produces the effect of simultaneous portrayal of Saul and the villagers. Handel articulates Saul's rage by thrusting us into the previously unused tonality of E minor (26). The sensation and direction of this abrupt shift away from any previously used tonal center is quite discernible to the listener. It is a striking example of Handel's calculated shifts of tonality for dramatic effect. The opening ascending arpeggio of an eleventh in the voice followed by the delayed instrumental ritornello also contributes to the dramatic impact. The following numbers (27-33 or C2), attempting to shore up this emotional break, are reactive and decrease the intensity through a temporary but pronounced shift in pacing. This change in pacing is brought about by shifts in length, tempo, form, key and mood. The foreshortening of numbers 20-26 in C1 accelerates the action; the pace of C2 is slowed by having numbers which are approximately twice as long as those in C1. The tempo markings of C1 are all Andante allegro; those of C2 are Largo, Lento, and Larghetto. The numbers of C1 show a variety of musical elements (symphony, recitative, chorus, accompanied recitative, aria); C2 resumes the alternation of recitative and aria, the symphony of 33 being the third strophe of 32. After the drastic shift to E minor in 26, C2 returns to previously used keys. There is also a shift in mood between C1 and C2. The stark simplicity of melody, form and accompaniment in C2 produces a tranquil mood, but it does not last. Saul's aria at the beginning of C3 jerks us to a high level of excitement and dramatic involvement. In this aria (35) Saul loses emotional control and throws his javelin at David. Handel sets up a da capo form. The ritornello pattern comes to a full close in the tonic, and the form is confirmed by the turning of the B section to the relative minor. Then, for dramatic effect, Handel overthrows our expectations and truncates the aria four measures into the B section, never returning to the A section. Handel manipulates the musical shape to reflect the dramatic events. The aria begins in B-flat major and ends in G minor.

This active sequence in 20-36 is followed by a compressed segment of reaction in 37-41. Merab's aria "Capricious Man" (37) is long by the clock and comes with particular spaciousness after the intensity of action in the previous numbers. Winton Dean calls the aria superfluous.7 However, besides being an excellent piece of characterization, its placement contributes to dramatic rhythm and effect. It provides the passage of time that is needed after Saul's command in 36 if Jonathan's soliloquy in 38-39 is to have its greatest effect. Jonathan's choice is agonizing. By delaying Jonathan's decision until after Merab's aria, Handel allows the turmoil of the situation to increase in the listener's imagination. The pent-up tension of this dramatic situation is then released musically at Jonathan's resolution in the second half of 39. The lyric pace of the concluding numbers by the High Priest and chorus (40-41) also provides a release of tension and a transition from the previous charged dialogues and soliloquy. The uncertain future course of the drama is reflected tonally: instead of returning to a previously used key center such as C major to form a closed structure, the last two numbers of the act employ D minor and G minor, two previously unused tonalities.

Dramatically, Act I is unified by the following elements: the forward linear movement along a single story line is sustained; the locale is the same throughout; the six characters introduced at the beginning of segment B remain on stage and are developed through the act; and the stage time nearly equals actual time. Tonally, the structure remains open; the act ends with the introduction of two new tonalities. Also new tonalities continue to be introduced in the first three numbers of the second act. (The C minor of 44 was used in the Epinicion but not by one of the main characters in Act I.) This open-ended tonal structure of Act I, and the dramatic development by manipulation of plot, locale, characters, and time setting of Act I, continue through the first segment of Act II. So the separation of the first two acts by frame choruses is more one of convention than of dramatic or musical structure.

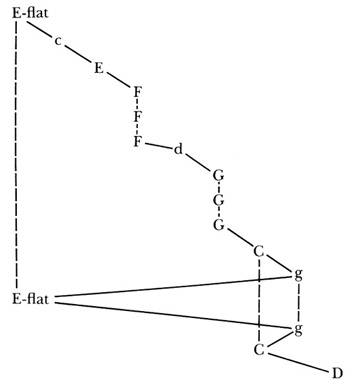

Whereas the numbers of Act I accumulate by the process of accretion, Act II (Tables 3 and 5) relies more on the juxtaposition of segments set in different times and locales.

TABLE 5

HANDEL, SAUL, ACT II: PROGRESSION OF TONALITIES

Segment A (42-54) continues as an extension of the dramatic and musical development of Act I. Jonathan's pleading (49) seemingly assuages the rage of Saul, but Saul's recitative (54) reveals his true intention. Nevertheless, this explosive situation is capped long enough to let the side plots develop. All the events of the oratorio are related to the actions of Saul, but the development and responses of the other characters in side plots assume more weight in Act II. The first half of segment A develops the friendship of David and Jonathan; segment B (55-58) involves the love and marriage of David and Michal; segment C (59-62) shows the heroic side of Michal; and segment D (63-64) relates the conversion of Merab. In segment E (65-68), the full rage of Saul reappears.

Segments B through D are relatively short by the clock, yet their placement midway through the oratorio interrupts the drive and temporarily disengages us from the tension of prior segments. Handel is simply contrasting primary or prominent events with secondary or subordinate events. This attention to shaping throws into sharper relief the high drama of prior and subsequent segments. Our attention to any presentation is not constant; we do not maintain steady concentration. Our interest and attention either increase or decrease. To maintain the same level of attention, a presentation must increase in interest. But the level of intensification cannot increase indefinitely. A rhythm of involvement and disengagement becomes mandatory, and it is this rhythm that provides the basis for theatrical segmentation. To cut these segments from Act II would eliminate the counterpoint to the dominant action and upset Handel's balance of involvement with and disengagement from the main action.

In contrast to Act I, C1, where the foreshortening of musical numbers quickened the pace, the placement of these short segments in Act II slows down the action, at least psychologically, by widening the space between the main events of the drama. When Dean remarked that "the scene for Jonathan and David [43-47] is best omitted" or that "little can be said for the next two airs"8 for Michal and Merab (62-64), he is probably implying a cut in order to quicken the dramatic pacing; he wants it to move more quickly. In so doing, he is imposing a modern concept of dramaturgy on an eighteenth-century convention which was not concerned with uninterrupted quick pacing.

For these juxtaposed segments of Act II, Handel uses contrasting tonal centers: C minor and E major for the friendship scene of Jonathan and David, the flat key of F major for Jonathan's attempt to calm Saul, G major for the love music of David and Michal, and to support the sense of impending danger, shifts to the minor mode for the duet of David and Michal (60). The heroic side of Michal's character is portrayed in an aria in E-flat major (62).

Act II also remains open-ended both tonally and dramatically. Tonally, the act ends in another previously unused tonality, D major. Dramatically, a single unifying dramatic concept continues to unfold across the divisions of acts: the theme of Saul's jealousy begins the act and, after development of the diverse side plots in segments B through D, returns with renewed urgency in segment E and continues through the first segment of Act III.

Act III (Tables 3 and 6) is in three dramatic segments.

TABLE 6

HANDEL, SAUL, ACT III: PROGRESSION OF TONALITIES

Segment A (69-73) which is the crux of the entire oratorio, begins at a high level of intensity. Handel whirls us into the action by the overwhelming power of his accompanied recitatives which allow him to instantly change pace or mood, to seize the audience by surprise. Abrupt change within a musical number is even more necessary and appropriate for a character who is now as mentally unstable as Saul. Segment A is the most intense of the oratorio. There are no elaborate arias, no orderly succession of recitative and aria to impede the flow of action, only an inexorable forward march, a crystallization of the inevitable tragedy foretold in the previous two acts. There are four recitatives for intensity and quick pacing, and each is vivid with action. Even the one aria (72) is not lyric or reflective in purpose but is acted and contributes to the forward thrust. The segment is fast-moving even though the tempo indications are Largo.

Segment B (74-76) relates the events of battle and the deaths of Saul and Jonathan; the inevitable swiftly comes to pass. The cast is greatly reduced in segments A and B: only Saul and David remain from previous segments. There are short appearances by the Witch, Samuel and an Amalekite.

The most noticeable feature of Act III is the length of segment C (69-86), the Elegy, which takes approximately twice the playing time of the previous two segments. The length of the Elegy may strain our patience, but Handel is observing a literary convention here in addition to building a musical structure. A conventional elegy begins with an expression of unadulterated grief, then modulates to a serene acceptance of the situation. A sudden shift between moods without sufficient time to let the sorrow subside would strain our credulity. (The turn toward the sorrow and lyric pace of the elegy began at the end of 76 in segment B.)

In other Handel oratorios, the last act portrays the death of a Biblical or mythical character (Samson, Hercules, Semele, Galatea, Belshazzar) which is followed by the same elegiac shift from grief to some admonition that life must go on. But no other Handel oratorio ends with the death of a Jewish king and his son in a war which Israel lost. The reaction of the characters to a situation of this gravity and magnitude demands as much time and attention as was given to any previous reaction, or more. What has happened cannot be passed over lightly or dealt with simply and quickly.

Handel is also using this segment to end the whole oratorio, and as the final segment, its length and weight help balance the design, strengthen the whole, and tighten the form. The lyric pacing continues throughout the segment, broken only for the short recitative before the final chorus. The segment gains concision by having fewer though longer numbers. (Segment C of Act I has twenty-two numbers in approximately thirty-seven minutes; this final segment has ten in approximately thirty-two minutes. And this number ten could be reduced to eight by considering 81-82 and 83-84 as just two musical units.) The musical mood and tonality of this segment parallels the elegiac shift: the chromatic writing of 79-80 turns to a more serene character softened by unobtrusive illustrative detail. The pivotal tonality of Saul, C major, is heard at the beginning of the segment (77, Dead March), then is avoided until the final chorus, where it is approached by key relations of the third.

Saul is perhaps the first oratorio which Handel took seriously, rather than composing for a quick financial profit. Freed from the constrictive conventions of opera seria, he created a fully articulated drama on his own terms. Of the opera seria conventions which Handel overthrew in his oratorios, four are clearly illustrated in Saul: (1) In Italian opera seria, the singers had to be allowed to sing. There was a structured social order of soloists that was not to be violated; that is, the lead singer sang the greatest number of arias, the next ranking singer had the second largest share of arias, and so on down the hierarchy of singers. In this oratorio, Saul sang only three arias, and nearly an hour of playing time elapses before he sings his first aria. This would have been totally unacceptable in opera seria. (2) Handel greatly reduced the number of da capo arias. Of the thirty arias in Saul, only five have the da capo. These structural changes suit Handel's placement of dramatic emphasis. But the opera seria audience was more interested in virtuoso singing than in a unified drama. It would offend their sensibilities not to hear their favorite singer in the embellished return of the aria's A section. (3) In Baroque oratorio and opera, the action is normally confined to recitatives while arias are reflective. Handel let the action affect the music, and his arias and duets often carry the action. (4) Handel also abandoned the repetitive scheme of recitatives and arias found in opera seria. Instead, he manipulated form sequence or scheme as the dramatic situation required. Sections of recitative and aria (Act I, segment B) alternate with sections predominantly choral (Act I, segment A) or predominantly arias (Act III, segment C). The different combinations of aria, recitative, and chorus make it impossible to predict what will come next. Handel manipulated musical conventions as well as musical forms to accommodate his dramatic synthesis.

Word paintings abound in Handel's music, and it is very easy to point out how and where the music does what the words say. But the casual listener can discover these for himself. This is not to belittle the practice or to deny that single word paintings have a cumulative effect. Since Handel lacked the opportunity to stage the oratorios, he necessarily concentrated action of all kinds in the music itself. So what may otherwise be just a matter of ordinary word painting or tone painting often lies at the very heart of Handel's creative style. Handel's sense of balance and feeling for context enhanced his use of word painting, for the details of this practice are effective only when related to what is past and what is to come.

While Handel seldom misses an opportunity to portray single words and meanings in music, he is just as effective when articulating larger units of drama and music. It is at the higher structural levels that we recognize the remarkable tautness of Handel's dramatic craftsmanship. Handel established his own convention of linking a continuous sequence of numbers so that larger units become nearly indivisible. The combination of several numbers into a continuous construction is a structural device associated more with the nineteenth century than with the eighteenth century. Handel uses it to unify scenes by accelerating the pace and carrying the dramatic tension forward into the next number. Individual numbers are accreted into continuous musical constructions or scenes (as noted above: 1-5, 17-19, 20-24, 32-33, 38-39, 49-51, 56-57, 81-82, 83-84), and these are built up into segments and acts. This forward dynamic thrust is further strengthened by eliminating or delaying the opening ritornello, as in numbers 4, 5, 18, 19, 26, 39, 41, 50, 57, 68, 82 and 84.

Handel also used music to set a mood or atmosphere. The first set of choruses for Saul (1-5) is regal in character, whereas the second set of choruses for David (20-24) conveys the feeling of village music. The two arias of Saul in Act I are in a style befitting a kingly figure. The other characters are drawn as effectively in their music: the arrogance and pride of Merab contrasted with the simplicity and sincerity of Michal, the soothing effect of David's harp playing, and the mysterious motive of the Witch's aria which carries into the following recitatives.

An examination of Saul's dramatic rhythms reveals the following alternation of static and active sections: 1-5 static, 6-19 active, 20-24 static, 25-40 active, 41-42 static, 43-67 active, 68 static, 69-77 active, 78-86 static.

The periodic return of C major for the symphonies and several choruses acts as a rondo element, unifying the oratorio tonally. Further, the actual sound or timbre of the chorus coming back periodically and sound and timbre of the symphony coming back also act as unifying elements. Throughout Saul the chorus functions as dramatic agent, or moral interpreter, or merely as contrasting voice; it is also used structurally, as a framing element beginning Acts I and II and ending all three acts. The Epinicion and Elegy, which are both static and have the tonal axis of C major, form framing blocks of sound at both ends of the entire oratorio.

Blume observed three tendencies of the Baroque feeling for group forms:

[1] the tendency to handle the beginning and end as independent parts related to each other (framing forms) or [2] to fashion in more ample shape some recurrent part of the text ('Halleluia' or such), repeating it as a salient pillar-like member (ritornello form), or [3] to connect constructions of this sort by means of a well-planned architectonic structure laid down around a central axis (symmetrical forms).9

The overall structure of Saul clearly reflects two of these: the beginning and end are handled as independent parts related to each other (both are static literary forms) and used as framing elements; and although no recurrent part of the text is repeated ''as a salient pillar-like member ," the repetitive return of C major, symphonies and chorus help fashion a ritornello-like form.

In our examination of Solomon and Saul, as well as in other Handel oratorios, we found that the musical numbers add up to a musical macrostructure and, at the same time, fit into the overall dramatic structure. This approach to the oratorios was initially through the libretto as dramatic literature; then the music was related to the dramatic structure. Since Handel had the librettos in hand before he composed the music, it is logical that in studying Handel's oratorios we approach them in the same order: words, then music. The music articulates and complements the drama, or the drama prescribes the musical form and style. The dramatic structures of Handel's librettos demanded great latitude in his compositional approach. Therefore, he had no perfect plan applicable to all the oratorios; the technical means by which he imposed unity on the total structure varied from oratorio to oratorio. Once a work was completed, he never repeated exactly the same overall formal structure.

The ways in which Handel incorporates the drama in his music, or incorporates his music in the drama include formal irregularities or manipulation of set forms;10 word and scene painting; declamation; sequence of tonality and abrupt tonal shifts; form sequence—the intermixture of solos, arias, ariosos, choruses, instrumental pieces, and ensembles; abrupt choral entrances or dramatic solo entries without any introduction or opening ritornello; dynamics; harmony; melody or lyricism; instrumental timbre or color and choice of instruments; manipulation of time; and dramatic/structural rhythms. Handel's use of these elements was conditioned by the nature and demands of the drama.

Dean suggests that "the extent to which Handel's towering edifices depend upon the foundations laid by [his librettists] will appear if the librettos are given the detailed attention they deserve."11 I have consistently followed this suggestion while applying Northrop Frye's approach in order to see how all the pieces fit into the whole dramatic structure. Therefore, when another author suggests that a particular number be cut, other reasons have been suggested why it should be retained.12 We must not divorce the text from the music, or else we miss Handel's point altogether. Lang warns that by examining the influences which converged on the English theater and examining the libretto only for its literary values and construction, modern critics have lost sight of the theater's value as "spectacle, dance, and music."13 But to fully understand Handel's process of wedding poetry and music, we must understand the literary source.

There is a fine line between ways we understand and respond to the libretto. We can read and be moved by the literary text and consider the addition of music as providing kaleidoscopic colors; or we may not be moved when we read the libretto, but the music makes up for whatever dramatic impact is lacking in the text. It is true that Handel's music could rescue a librettist and was often the deciding factor in the success of the oratorio. Similarly, Beethoven could fashion a masterpiece from a discarded, second-rate theme; Mozart used nursery rhymes. In such instances, the subject matter—literary or musical—is sometimes irrelevant. The music can carry a dramatically weak text, or the text may carry the drama while the music is perfunctory. Although this study maintains that music and drama are complementary in Handel's oratorios, the literary subject matter could and certainly did influence Handel's compositional style. And until we consider the literary style of the period, the subject matter in the world of Handel's stage will remain as much an anachronism to us as the grand style of emotional acting on the Restoration theater stage commonly referred to as "ham acting." Until we move beyond our prejudices, we will continue, as we listen to productions of Handel's oratorios, to be thankful—as was Tovey—when the text is lifted verbatim from the Bible, that we are thus "spared the duty of keeping our tempers and restraining our guffaws at the well-meaning absurdities of Handel's librettists."14 Sometimes it is more difficult to overcome prejudice than to acquire knowledge. Not until we take the librettos seriously as drama can we understand the complementarity of Handel's musical structure.

1Northrop Frye, "Literary Criticism," in The Aims and Methods of Scholarship in Modern Languages and Literatures, ed. James Thorpe (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1963), pp. 63-64.

2Bernard Beckerman, Dynamics of Drama: Theory and Method of Analysis (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970), p. 20.

3Performances of Handel's oratorios (other than Messiah) are infrequent, and staged performances are rare. Commercial recordings most often provide the only way to hear these works yet the full dramatic experience cannot be communicated outside the theater. Furthermore, the live performances and recordings we do hear are often so cut or abridged as to destroy the works' original dramatic and musical shape. "Handel can never be understood with the mind alone," Dean insists; "he requires the ear, and very often the theatre as well." Handel's Dramatic Oratorios and Masques, p. 50. The numerous stage directions in Handel's autographs indicate that, although he was prevented from staging his works, he envisioned the oratorios as stage performances. He was working with visual theater as well as musical sounds. Belshazzar is perhaps the most highly unified and organic drama Handel set to music, and the stage directions in the autograph are richer and more vivid than those for other oratorios. The various strands of action are clear and straightforward, and fit well, but the work will sound disjointed if the listener does not follow the stage directions and use them to clarify the dramatic situations. These directions are essential for contexture where segments join. Without them, the listener loses all sense of continuity at the dramatic joints. Even with the stage directions at hand, the listener must visualize the works (à la radio drama), and the scene changes still require the listener to make mental adjustments that interfere in a concert version. A staged version is needed to receive the full impact of the drama's visual aspects. Just because Handel was prevented from staging his works is no reason that we should not stage them.

4Bertrand H. Bronson, "The True Proportions of Gay's Acis & Galatea," PMLA 80 (1965), 325.

5The numbering given here follows Chrysander's edition. The librettos should also be studied in their entirety. In Tables 1 and 3, the "Sequence of Form, Tonality, Tempo" also shows the approximate timing for the dramatic segments. For referral purposes, the numerals which order these lists follow the numerical references found in the narrative. In other Tables, the order of appearance of arias and choruses in "Tonal Centers/Relationships" and "Progression of Tonalities" is charted from the top to the bottom of the page. As new keys are introduced, they are positioned to the right of the previously used keys; and when a key is repeated, it is placed on a vertical plane underneath previous uses of that key. But in all cases, the successive musical numbers are placed on the next line down, with these connections indicated by a downwardly slanting line. Any vertical lines, whether solid or broken, are merely aids to see repetition of tonal centers.

6The numbering given here for Saul follows the Hallische Händel-Ausgabe.

7Winton Dean, Handel's Dramatic Oratorios and Masques (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 289.

8Dean, Oratorios, pp. 290, 291.

9Friedrich Blume, Renaissance and Baroque Music, trans. M.D. Herter Norton (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1967), p. 136.

10Handel's formal irregularities never fail to be effective. He knew that in a fixed form such as the da capo the slightest deviation has a disproportionately weighty effect. Particularly effective are the times he uses two Affekte within the same aria, articulating a dualism of text by a dichotomy in the music. It is a short step from this kind of form to the dualistic forms of the later eighteenth century. Handel so chose his formal types and so placed them as to draw the main threads of the drama together.

11Dean, Oratorios, p. 277.

12Before cutting any number from Handel's score we should, at the very least, ask whether the cut will weaken the dramatic structure or if it will unbalance Handel's tonal structure. If the answer to either of these questions is affirmative, then the cut will most certainly damage Handel's or the dramatist's fabric; and the listener will probably experience an unsettling jolt at that juncture, even if the listener is not sure why. Many listeners experience this same jolt when the "Hallelujah Chorus" is inserted to conclude Messiah, regardless of what has gone before.

13Paul Henry Lang, George Frideric Handel (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1966), p. 259.

14Donald Francis Tovey, Essays in Musical Analysis, Vol. 5: Vocal Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1937), p. 86.