Probably because its meaning is so obvious, the term tempo di minuetto is not usually found in modern musical dictionaries.1 In instrumental music of the early Classical period, it is frequently encountered as the last movement of a sonata cycle, sometimes with an additional marking such as allegretto or grazioso. Structurally, these minuet-finales are usually expanded far beyond the original bipartite matrix in order to accommodate more elaborate formal designs such as sonata-allegro or rondo forms. The finale of Mozart's Concerto for Violin in A Major is a well-known example. It is an extended rondeau with a beguiling pseudo-Turkish intermezzo as the central couplet. But the overall tempo and character are reminiscent of a Rococo minuet.

Most modern writers pay scant attention to the tempo di minuetto marking, taking its meaning more-or-less at face value to denote a moderately paced tempo in three-quarter time. Rothschild concedes that whenever the superscription is used, "the tempo and the accentuation were those of a minuet in the Style Galant, which was appreciably slower" than the more highly stylized classical minuet.2 Dorian acknowledges that "tempo di minuetto in cyclical forms is frequently but a recollection of the earlier dance minuet."3

It is important to remember, however, that for the eighteenth-century musician, many traditional Italian tempo markings had more subtle shades of meaning than are conveyed to present-day performers. Vestiges of the Baroque Affektenlehre remained in the musical consciousness of composers and performers well into Mozart's time. Bound up with the tempo of a piece was its basic "affection," and such theorists as Quantz, Leopold Mozart, Tk, and Löhlein devoted portions of their treatises to the elusive quality of feeling and expression in musical performance. Quantz, for example, cites a category of tempo markings (e.g., cantabile, maestoso, adagio spiritoso) which he says "refers more to the expression of passion that predominantly governs each piece than to the tempo itself."4 Although tempo di minuetto is not included in Quantz's examples, a comparable term, alla Siciliana, is mentioned. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that at least under certain circumstances tempo di minuetto could have been similarly understood as evoking a certain social ambiance in addition to a specific tempo.

One minor Italian theorist and composer, Giorgio Antoniotto, writing in London in 1760 suggested "that perhaps in the mind of the public the affective qualities of tempi may have had an unconscious connection with the dance: the movements of the jig, boree [sic] and correntes, for instance, showing a connection with the brisk and lively tempi, the sicilianes and sarabands with the adagio or affettuoso, and the minuettos for the allegro gratioso."5

We know that it was the function and position of a dance which dictated its tempo and interpretation. Whenever the minuet retained the more fundamental characteristics of the actual dance, it was probably performed in a moderate tempo. In another context, when the minuet became a highly stylized affair inserted between nondance movements in a cyclical form, it was obviously not meant for dancing and could be played faster. Dorian aptly states that "the features of the minuet were assimilated to an astonishing degree by new formal conditions in changing centuries. Its tempo runs through the entire gamut of speeds, from extreme slowness to the greatest rapidity."6 To complicate matters, there are numerous instances of texted minuets such as are found in Baroque and Classical opera arias. What should be the interpretation of these vocal minuets? This is a matter virtually ignored by eighteenth-century writers on music, undoubtedly because singers had the advantage and freedom of being guided by the specific emotions and moods conveyed by the text. It is precisely this question of the overall mood or character, suggested not only by the text but through the dance itself, that this article will survey, with particular attention to Mozart's operas.

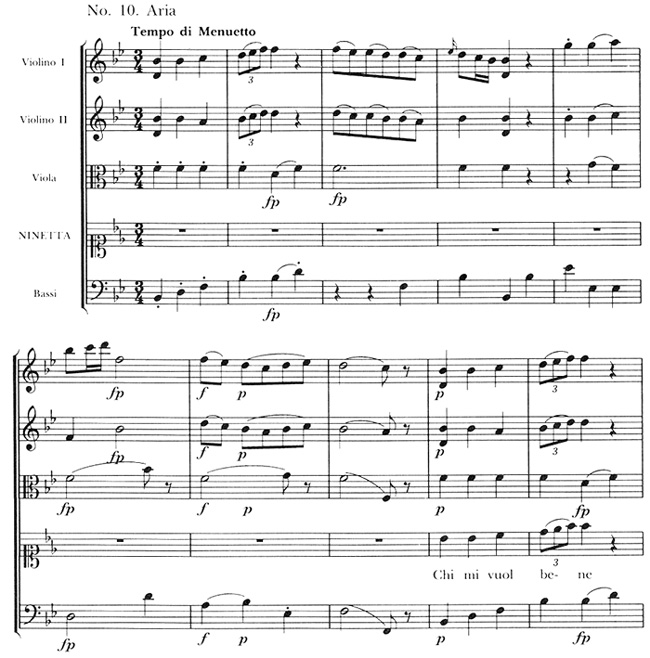

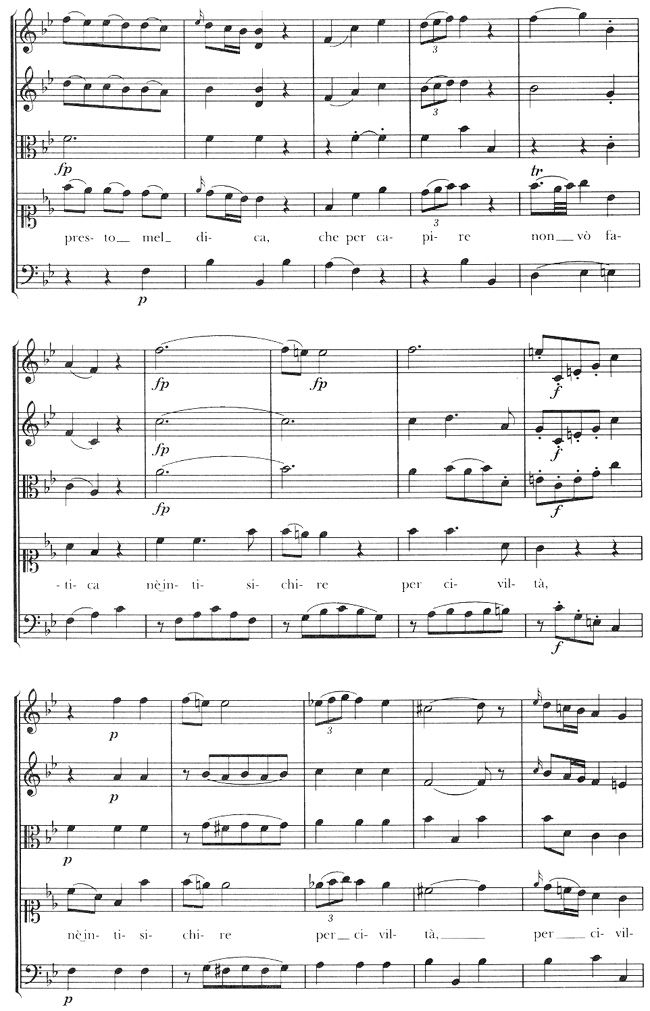

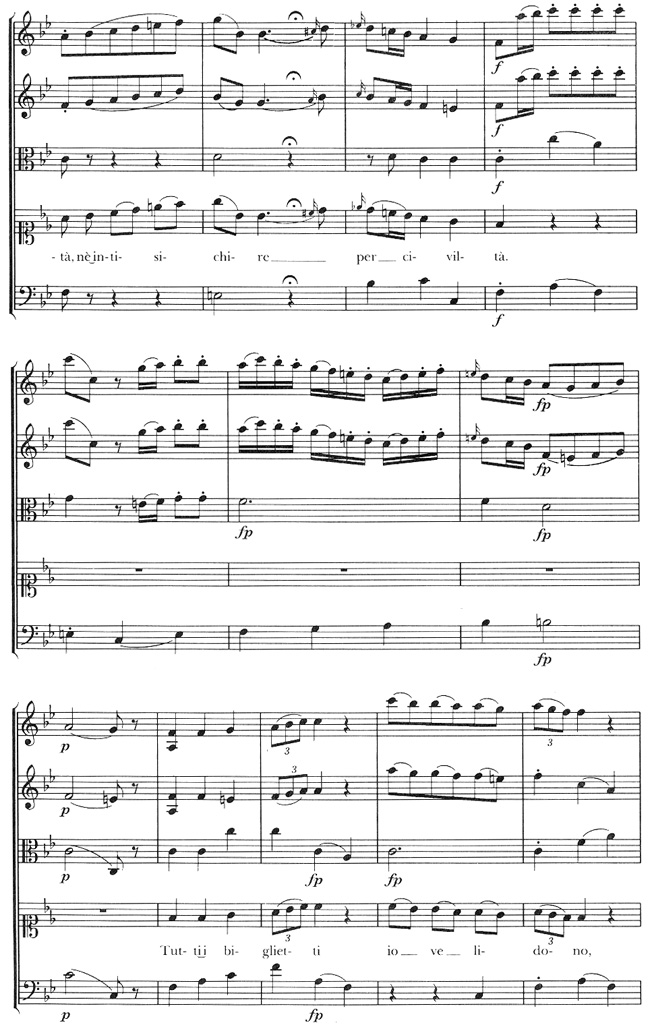

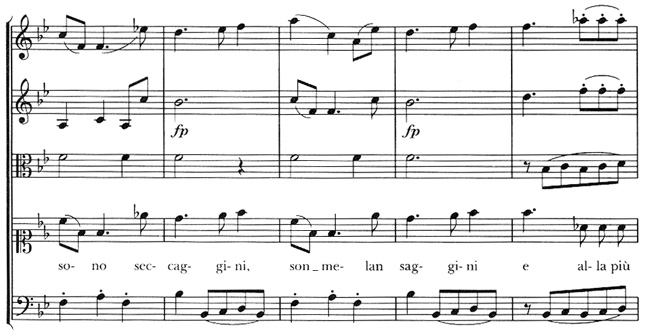

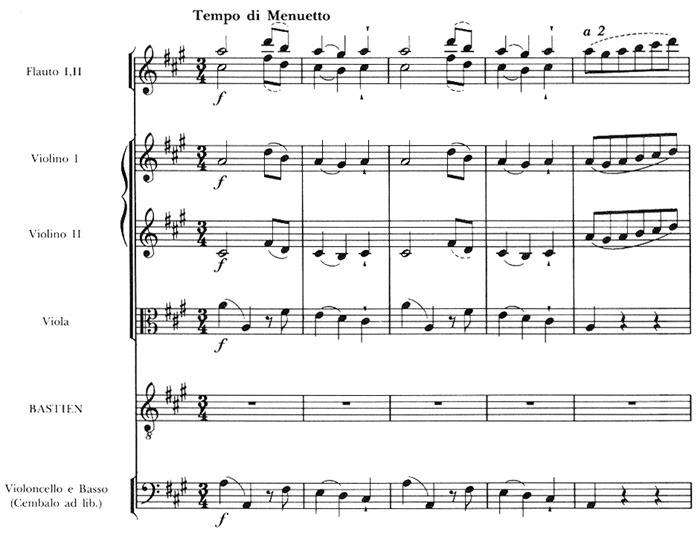

We may begin by examining briefly the two tempo di minuetto arias in Mozart's first opera, La finta semplice, composed at the age of 12. Both are assigned to the chambermaid Ninetta, a type of role known as damigella in Italy, or what the French call a soubrette. Her first solo ("Chi me vuol bene," No. 10) occurs in Act I when she sings of her preference for the kind of man who would tell her directly that he loved her, rather than one who hides behind formality and love letters. "All business," she sings, "is quickest transacted in person."7 This is a rather stilted, formal air, well-suited to a chambermaid, but the little harmonic surprises and phrase extensions betray Ninetta's cunning.

Ex. 1 La finta semplice

It is plausible that Mozart intended for Ninetta to "put on airs" in this aria by making the vicissitudes within the lowly minuet a device of irony or parody. The binary form, so typical of Mozart's early opera arias, is not so strict as that of an instrumental minuet.

The only other tempo di minuetto aria is Ninetta's exit aria in Act III ("Sono in amore," No. 23) in which she reveals her desire to marry any man, "even if he were the first passerby." The minuet tempo alternates with a more agitated 3/8 allegro section in which Ninetta warns of the consequences to anyone who mistreats her: "I will scratch out his eyes like a cat, I will use my nails with such abandon, that scars he'll bear forever."

Einstein speaks of this aria as one of the typical situation jokes deriving from the commedia dell'arte, calling it an "explosion of the man-crazy chambermaid, in which one can just recognize Goldoni."8 However stereotyped, this aria does in fact reestablish the character as well as intensify her shrewdness of temperament. The 3/4 sections are similar to the tone of Ninetta's first aria (No. 10) and reveal her surface charm and composure as only a minuet can. But the 3/8 allegro sections, while swifter and more declamatory, and in slightly more taxing tessitura, do not entirely abandon the minuet character. The difference, as usual with Mozart, is very subtle. While there is no denying that Ninetta is merely an operatic type modeled on the Columbina-Serpina figure, at least the 12-year-old Mozart was aware of the musical conventions required for such a role. We must remember, too, that he tailored his arias for specific singers, in this case Antonia Bernasconi, who earned her early fame in such soubrette roles. If nothing else, Mozart laid the foundation for such later creations as Zerlina, Despina, and Blonde, although by then he would no longer use minuet-arias to characterize them.

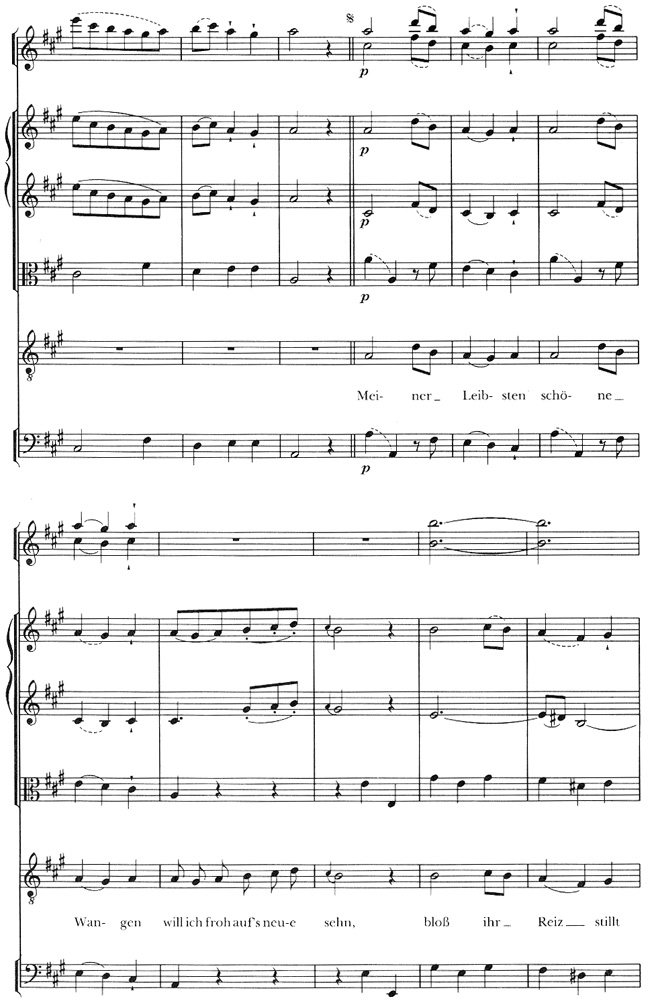

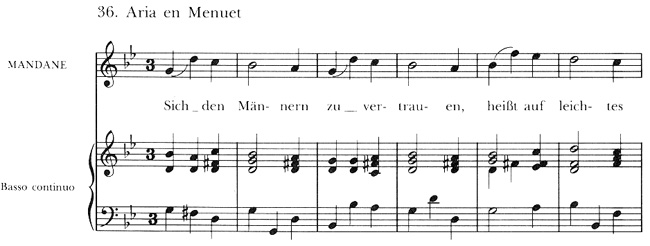

Mozart's second opera, also composed in 1768, is the better-known Singspiel, Bastien und Bastienne. The libretto is a German translation and adaptation of Favart's parody of Rousseau's popular opéra-comique Le Devin du village of 1752. The sole tempo di minuetto aria ("Meiner Liebsten schöne Wangen," No. 11) is given to Bastien and is heard after the soothsayer's incantation in gibberish. Bastien has just been duped by the soothsayer into believing that his beloved has forsaken him for another. In his minuet-love song, which Mann calls a "frenchified rococo chanson," he eagerly awaits the chance to behold his "darling's pretty cheeks again" to undulating phrases that match the naive tenderness and charm which permeates the entire score.

Ex. 2 Bastien und Bastienne

Another triple meter aria from this Singspiel ("Wenn mein Bastien einst im Scherze," No. 5) is marked Tempo grazioso, but curiously not designated tempo di minuetto. Closer inspection reveals that its phrase structure and rhythmic accentuation deny it true minuet status.

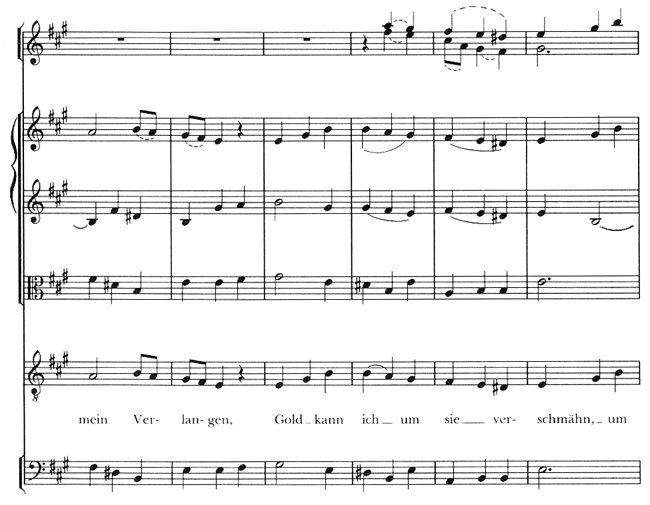

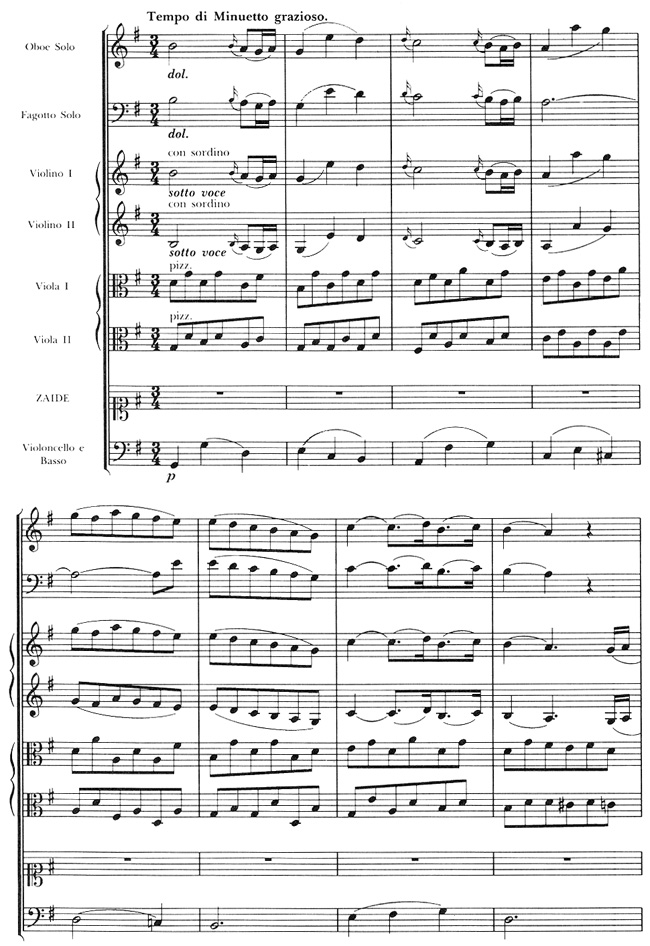

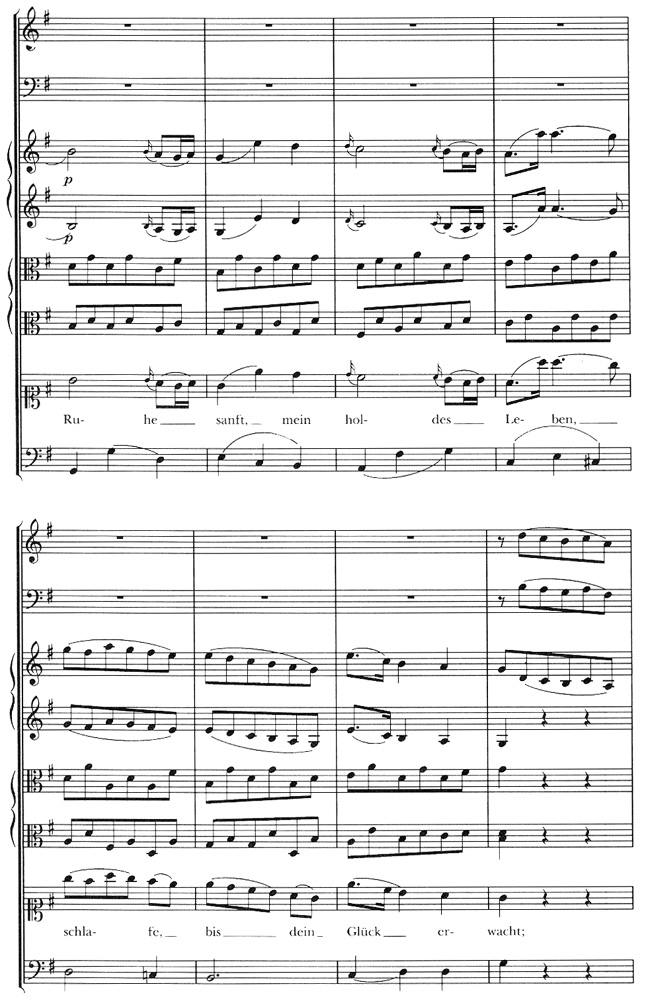

At least once, however, Mozart did add the word grazioso to a tempo di minuetto aria which affected its interpretation. It appears as No. 3 ("Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben") in the unfinished Turkish Singspiel today known as Zaïde. As with Bastien und Bastienne there is a connection with earlier French plays and operas on similar subjects. Mann claims that the French style of such composers as Grétry and Gluck was a principal source for Mozart's German opera style from Bastien to Zauberflöte. It is evident nonetheless that the character of many of the solo numbers in this work is not Italian, but more in the popular Austrian and French traditions.9 "Ruhe sanft, mein holdes Leben" is a graceful slumber-aria which Zaïde, the Sultan's favorite, sings to the sleeping Gomatz as she deposits her portrait beside him. The slightly quicker pulse of the middle section, andante moderato in 2/4 meter, is less supple and suave and suggests her anxiety over Gomatz's safety. The character of the minuet sections is modified somewhat by the continuous eighth-note motion in the divided violas pizzicati against muted violins. The oboe and bassoon solos add piquancy to the text. Clearly, the grazioso marking was not superfluous.

Ex. 3a Zaïde

Ex. 3b Zaïde

Because of the explicit literary and musical indebtedness of Bastien and Zaïde to French models, this may be a good opportunity to digress long enough to comment on the genesis of the minuet-aria in French Baroque opera and related genres, as well as to summarize general developments in dance-related arias leading to Mozart.

Despite the French beginnings of the minuet, it seems that the idea of employing dance rhythms in operatic arias originated in Italy as early as Caccini's times. This is certainly due to the pervasive influence of ballet, popular at first at Italian courts throughout the sixteenth century, and introduced to French courts in 1533.10 Robinson points out:

The connection between aria and dance is not surprising considering the popularity of ballets at court and the artistic closeness of the two genres: opera and ballet. Some operatic songs accompanied dancing; others were based on dance tunes heard in the same work. . . . The fashion for triple-time arias, which reached its apex in the middle of the [seventeenth] century, was connected with the fashion for certain dances. Sarabande, corrente and minuet rhythms became popular in arias.11

In France the prototype of the tempo di minuetto aria was a variety of the air de cour known variously as air de danse or chanson à danser. Michel Lambert among others composed vocal airs incorporating the rhythmic organization of the sarabande and minuet. Le Cerf asserted that such airs served as models for Lambert's famous son-in-law Lully, who easily absorbed them into his ballets and operas.

Lully has learned how to use his dances as models for dance songs in the comédie-ballet. In the tragédie lyrique as in the comédie-ballet, the simplest treatment is an addition of text to a direct repetition of the instrumental dance. There are, however, several examples of dance songs in which the dance model is freely varied in the vocal version. This often leads to a subtle, well-developed paraphrase technique. Lully accomplished this through altering the phrase structure by contraction or elongation or by retaining the model's phrase grouping and rhythmic structure but changing the melodic and/or harmonic organization.12

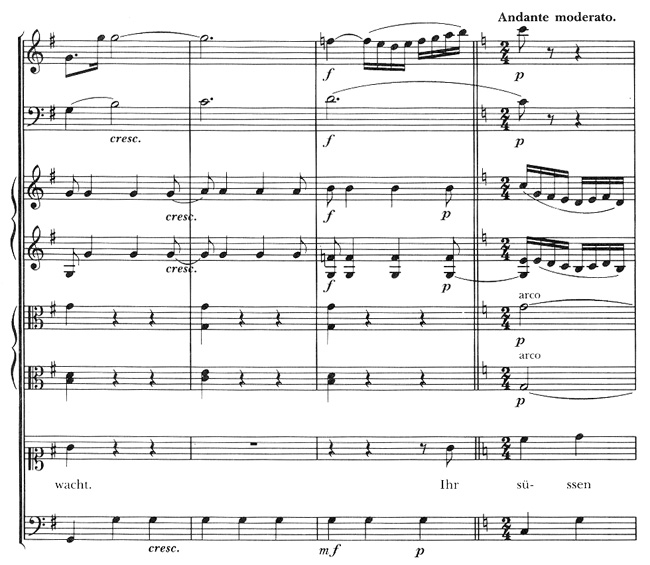

Already in Lully's first opera, Cadmus et Hermione (1673), a texted solo minuet with choral refrain is heard at the conclusion of the prologue before the repeat of the overture. In the last act is the familiar aria "Amante aymez vos chaines," referred to in the score as a menuet chanté; its two strophes are separated by an instrumental minuet.

Ex. 4 Cadmus et Hermione

Further cross-pollination of French vocal and instrumental forms occurred during the vogue of the opéra-ballet between 1697 and 1735 with such composers as Campra, Mouret, Destouches, and Rameau.

German opera at the turn of the eighteenth century, especially under Reinhard Keiser, was an eclectic genre of nearly equal Italian and French influence. Nettl, in characterizing the German preference for a synthesis of the various theater arts, observes that the German opera lover "like the Frenchman, . . . was a rationalist; he could and would not subscribe to the unnatural heroic cult of Roman emperors and Greek gods whose bombastic personalities were all too often expressed incongruously by the graceful rhythm of gavotte and minuet."13 This statement notwithstanding, dance-related arias are as prevalent in German operas, especially those of Mattheson and Telemann, as in French and Italian operas.

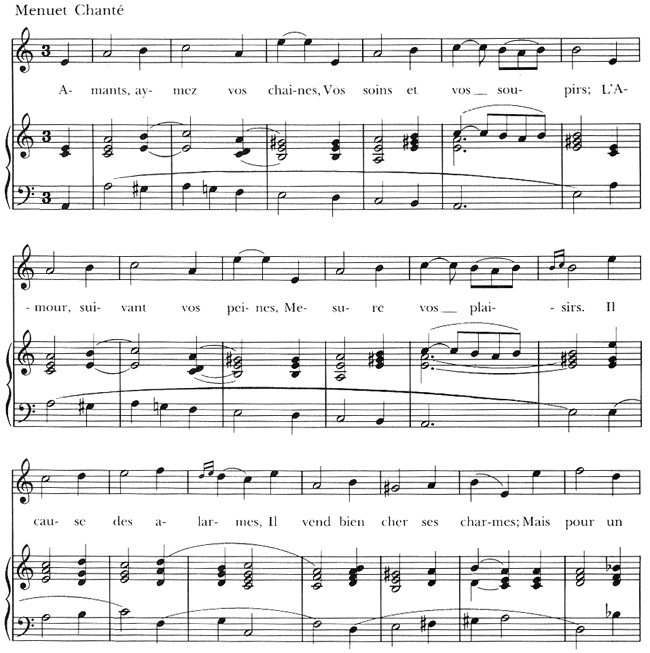

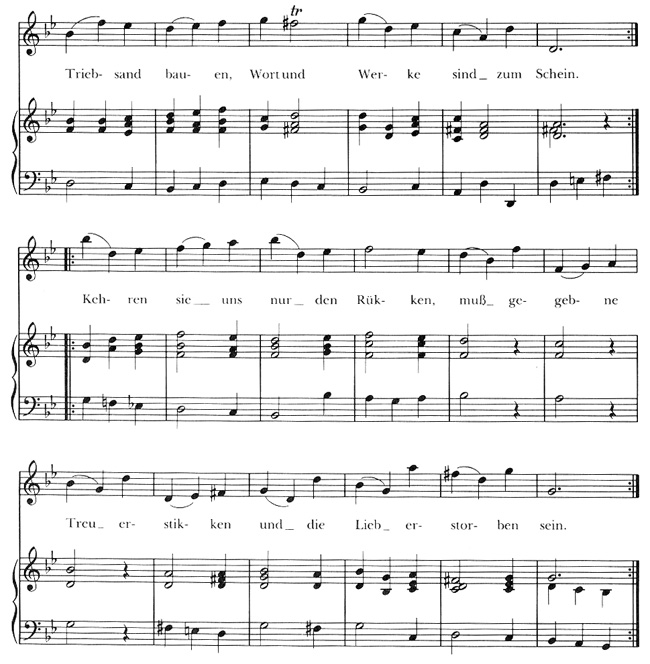

Of Mattheson's five operas, the second, Porsenna (1702), has arias which "are all written in the rhythms of the gigue, rigaudon and minuet, [and] are short and vocally simple."14 In Mattheson's third opera, Cleopatra (recently published in a modern critical edition as Volume 69 of Das Erbe deutscher Musik), two vocal numbers are designated aria en menuet. Once again, both are short and simple. The more interesting one, in G Minor, occurs in Act I. It is in symmetrical binary form with 12 measures in each section and mostly in two-bar phrases. A reviewer of the modern edition wrote that this aria "portrays a woman's mistrust of men by means of a bitter-sweet minuet clothed in a serious minor key, with broad leaps and twists in the melodic direction to reflect insecurity and disillusionment."15

Ex. 5 Cleopatra

Handel, a close friend of Mattheson's and one who also cut his operatic teeth on Keiser's operas while in Hamburg, seems to have eschewed the minuet-aria, although several arias show the influence of other dances such as the siciliano, sarabande, and gavotte.16 In Gluck's reform and pre-reform operas, dance choruses in 3/4 or 3/8 time abound, as well as a few triple-meter arias referred to as air chanté et dansé (e.g., Echo et Narcisse Act, I Scene 1), but no tempo di minuetto arias as such.

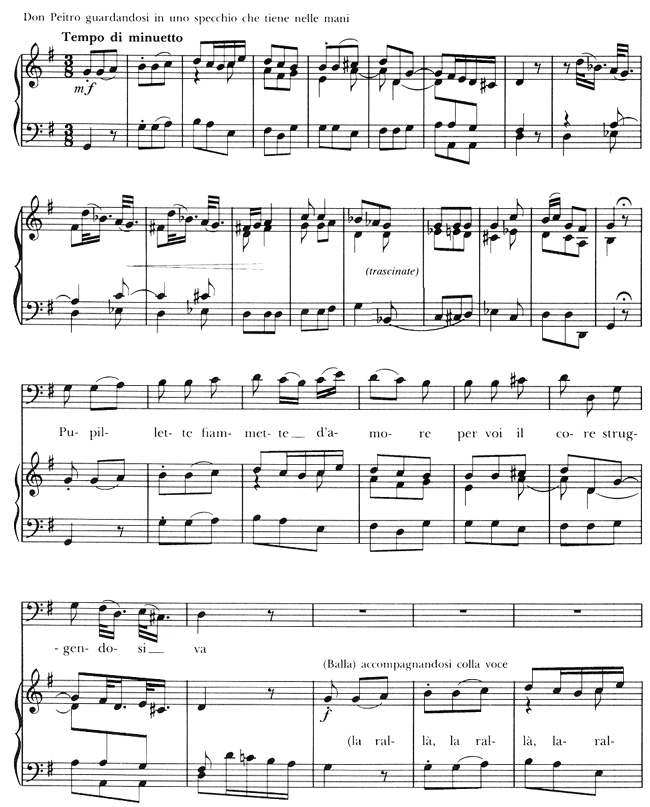

In Italian comic opera of the first half of the eighteenth century, the minuet-aria played only a minor role. One instance occurs in Pergolesi's three-act commedia musicale of 1732 entitled Lo frate 'nnamorato, in which the comic bass, Don Pietro, sings and dances a minuet while admiring himself in a handmirror. No doubt the intention here is to caricature the elegance of the more refined and aristocratic French minuet.

Ex. 6 Lo frate 'nnamorato

In opera seria at this time the minuet-aria was evidently incompatible with the pompous and heroic sentiments of the dramatis personae. We read in Goldoni's memoirs (1787) of the rigid conventions he was forced to observe in writing an opera seria libretto of 1733:

The author of the words must furnish the musician with the different shades which form the chiaroscuro of music, and take care that two pathetic airs do not succeed one another. He must distribute with the same precaution the bravura airs, the airs of action, the inferior airs, and the minuets and rondeaus.17

It seems likely that Goldoni's faulty memory at the time he wrote caused him to intermingle seria and buffa aria forms, since as Robinson alleges minuets and rondeaus were not generally employed in opera seria of the 1730s, but could sometimes be heard in opera buffa.

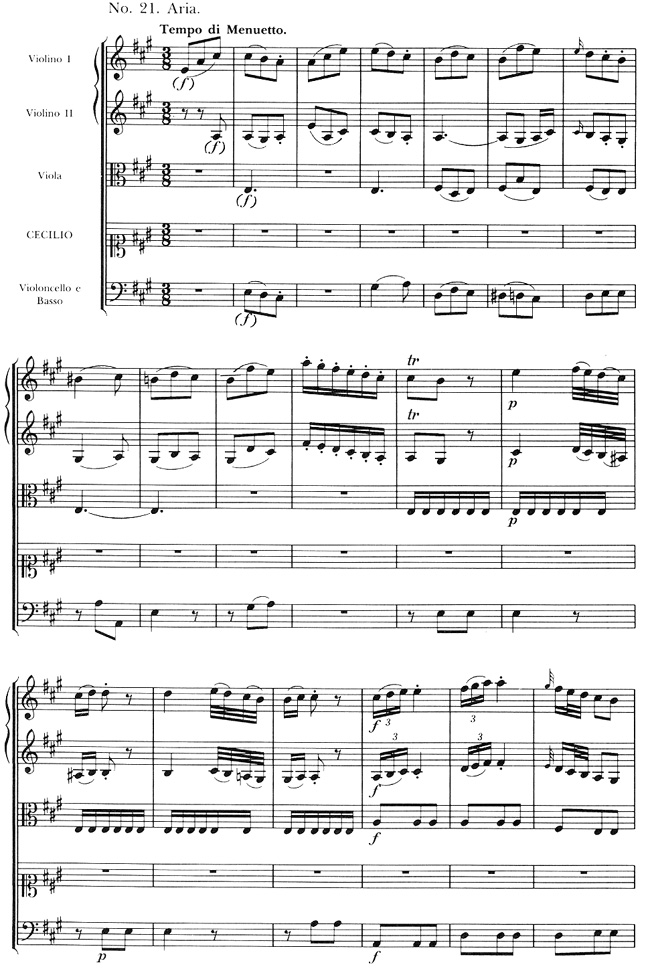

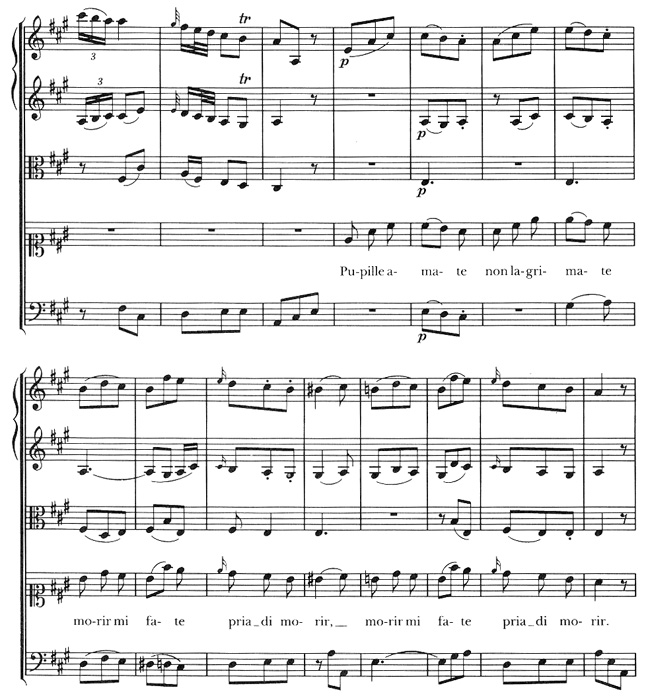

Returning to Mozart, we find that by the time of his Lucio Silla (1772) the minuet aria as well as other features of opera buffa had crossed over into opera seria, a situation regarded as a shocking breach of tradition and one which was partly responsible for Mozart's inability to secure another Italian commission. Of the many masterful departures from the traditional formula which occur in Lucio Silla, "the arias show that far more than in previous works Mozart dismissed convention and put his mind to the text. Significantly, these arias are in two contrasting parts, a form which opera seria has lately taken over from opera buffa."18 The sole tempo di minuetto aria in this opera, however, is exceptional in that it is cast in small rondo form. It is sung by the proscribed Roman senator Cecilio, who everyone believes will be sentenced to die by Lucio Silla, dictator of Rome. His farewell sentiments ("Pupille amate," No. 21) to his wife, Giunia, are expressed in music which "to the post-romantic ear . . . may seem flippant, almost Dorabella-like."19

Ex. 7 Lucio Silla

Once again we must bear in mind that Mozart was equally interested in satisfying the vocal requirements of specific singers. In this case the role of Cecilio was written for the castrato Venanzio Rauzzini, for whom Mozart also composed the motet Exsultate, jubilate. Mann states that Rauzzini's voice "was beautiful but not very large" and that Mozart accommodated him in this aria with a "vocal line calculated with miraculous suavity and tenderness."20

The last of Mozart's early operas to be considered here is La finta giardiniera, composed for Munich in 1775 on a text by Calzabigi. The highly organized ensemble-finales in this work forecast those in Figaro. But since the original Italian text for Act I is lost and only a German translation survives, the opera is usually performed as a Singspiel. No full-length tempo di minuetto arias are used, but a curious minuet conclusion to Count Belfiore's "mad scene" in Act II serves as a kind of stretta. The purpose of the minuet in this context is satirical. The leading tenor, after ranting incoherently in his aria ("Già divento freddo freddo," No. 19), suddenly calms down to the "normality" of a tempo di minuetto ("Che allegrezza") expressive of rapture and joy. The caricature is unmistakable because of the inordinate amount of tone-painting applied by the orchestra, in which the images correspond more to the German than to the original Italian text.

It is no coincidence that Mozart virtually abandoned the tempo di minuetto aria in operas after La finta giardiniera. By the 1780s the minuet itself was rapidly fading from social circles and its outmoded style was ill-suited to more realistic plots, or at least to characters of greater emotional depth. On rare occasions when Mozart did resurrect the form, it was a deliberate archaism and invariably intended for secondary characters.

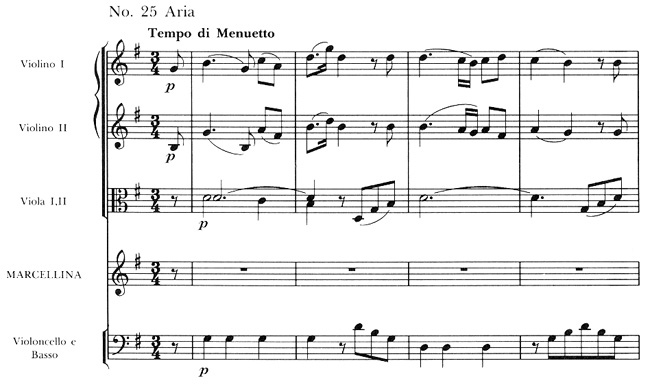

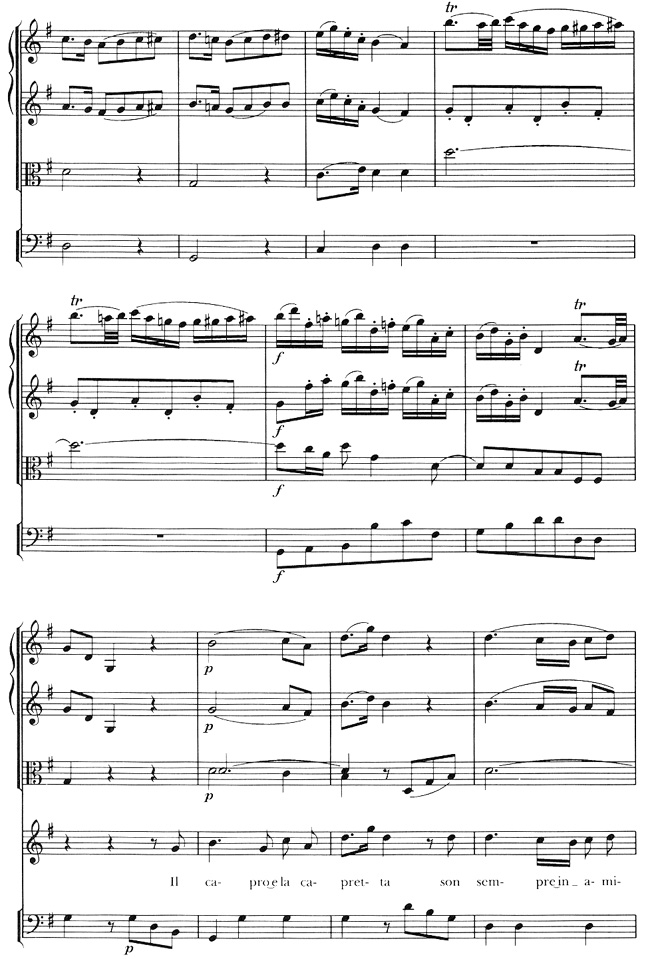

In Le Nozze di Figaro, two tempo di minuetto arias (Nos. 24 and 25), both quite perfunctory and superfluous, are given to Marcellina and Basilio in the last act. Marcellina's stolid, bourgeois aria, "Il capro e la capretta" ("The he-goat and the she-goat are always good friends"), merely reinforces her matronly image and alludes to her middleclass aspirations.21

Ex. 8 Le nozze di Figaro

Mann wonders if Mozart and Da Ponte really intended for us "to imagine these pairs of animals peacefully cavorting in a stately dance-measure," adding that Abert "regarded it as a deliberate joke."22 Marcellina reverts to her former, shrewder self at the allegro 4/4 where she asserts, "Only we poor women, who love these men so much, are always cruelly treated by these wicked fellows."

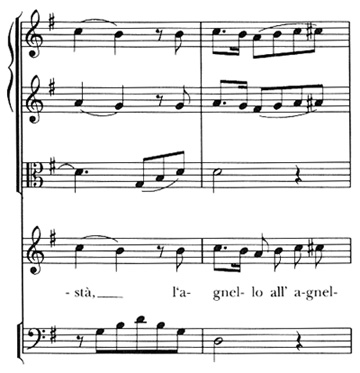

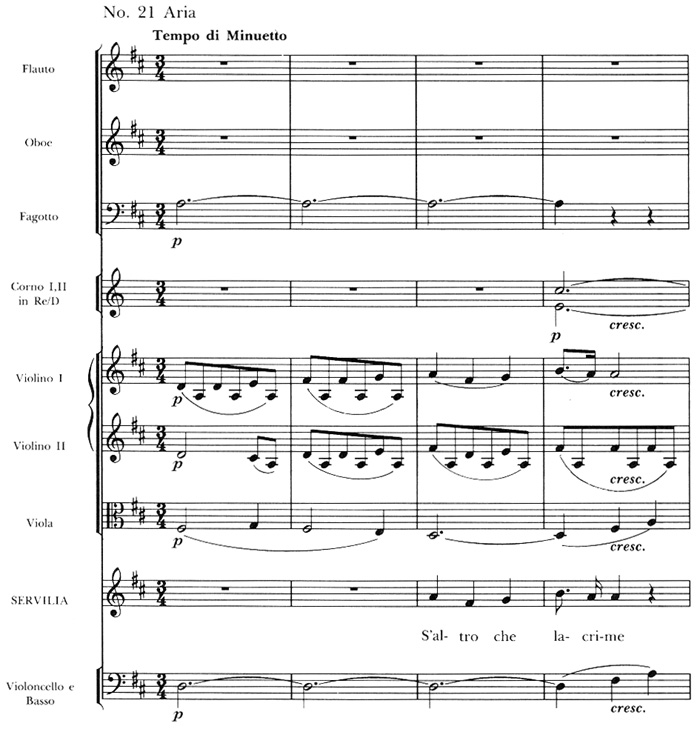

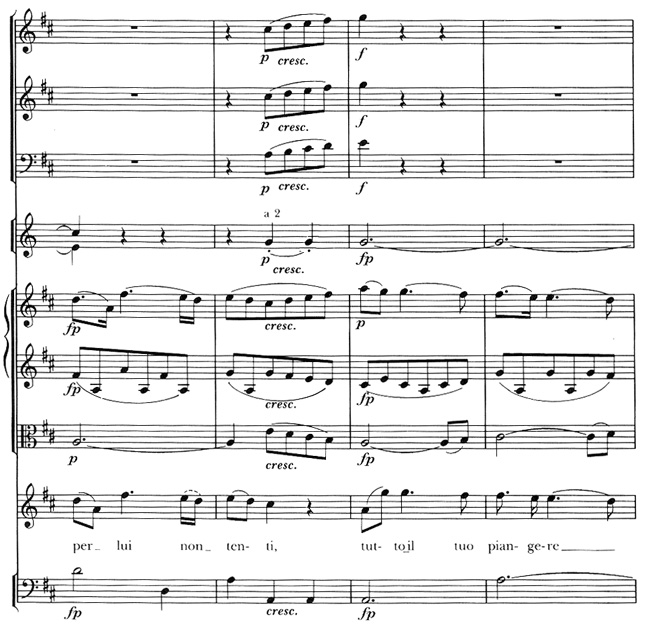

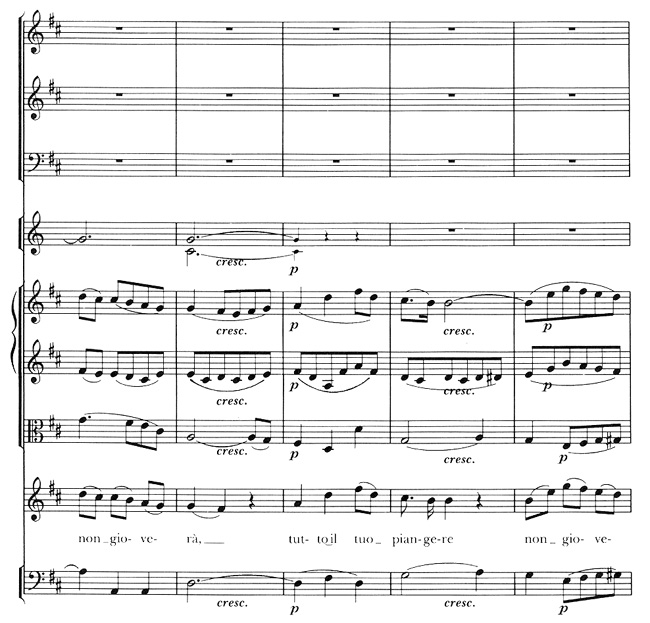

Mozart devised a somewhat more convincing place for a minuet aria in La clemenza di Tito, even thought it is assigned to Servilia, a puppet-like supernumerary who would otherwise have no solo number in the last act. In context, Servilia's brief aria, "S'altro che lagrime," (No. 24) is the plaintive vehicle through which she implores the weeping Vitellia to intercede with the Emperor (Tito) to spare the life of her brother Sesto. That she does so to the strains of an innocuous minuet may have struck an earlier generation as incongruous. Yet for all its innocent charm, it is remarkable that Mozart could infuse it with so much pathos. This is due in large part to the euphonious strings and woodwind scoring which allows the music to convey its doleful message without lapsing into bathos.

Thus, at a time when the tempo di minuetto aria was passé and dramatically regressive, it is not a little poignant that Mozart, working in the final months of his life, could yet revitalize the demure minuet and find still another use for it. And in an opera seria, of all places!

Ex. 9 La clemenza di Tito

In summarizing the function of the tempo di minuetto aria in Mozart's operas, one is immediately nonplussed at the composer's versatility in accommodating the characteristics of the dance to the variety of situations and moods posed by the libretto. What Dorian writes of the instrumental minuet is equally true of its vocal counterpart: "facing such a diversity of purposes, it is a complex task to define the character of the minuet, even if we limit ourselves to a single period. With so many changes of function the form eludes generalization."23 It seems safe to assume, however, that the tempo di minuetto superscription did not necessarily imply merely the speed of the music in question. In Mozart's time this would have been taken for granted to mean a more-or-less moderate triple meter tempo, except when an additional marking qualified it. Tempo considerations, in any case, were still largely determined by the time signature, the note values, and in vocal music the kinds of emotions expressed by the words themselves. What was more important was the aesthetic connotation conveyed by the word minuetto, and how this might symbolize particular traits of the character within the context of the drama. Accordingly, three non-exclusive categories of minuet arias may be distinguished:

1. In opera buffa, where stratification of characters by social class was the norm, tempo di minuetto arias might be useful in depicting persons of inferior rank as could be deduced by the minuet's formal simplicity, especially if it were rendered in a stolid manner. Comic irony and burlesque may also be suggested by the juxtaposition or superimposition of lofty sentiments conveyed through a rather pedestrian musical style.

2. In the Singspiel, due to the impact of French and popular influences, tempo di minuetto may allude to a somewhat bourgeois quality of naive tenderness and charm, or sometimes to a kind of urbane elegance.

3. In opera seria, whenever pathos and poignancy are required, tempo di minuetto may intimate plaintive feelings or bitter-sweet ironies. Here the mood is usually dignified but old-fashioned, like opera seria itself. In such a context the tempo is likely to be slower than minuet arias in comic operas.

Stylistically, there is no precise pattern evident in Mozart's choice of keys, or any consistency in his use of obbligato instruments for tempo di minuetto arias. Depending on how the character needed to reveal himself, phrase structure is either annoyingly predictable or refreshingly irregular. Formally, minuet arias tend to be of modest dimensions and sometimes act as contrasting sections or epilogues to larger arias. The forms are the same as those Mozart ordinarily employed: mostly binary in his youthful operas (with or without rudimentary sonata influence), A-B-A in the majority, and less often rondo form.

It seems that without Mozart, the tempo di minuetto aria would have died out somewhat prematurely and unworthily. With Mozart, it expired with dignity.

1Although minuet is the accepted spelling in English (and minuetto in Italian), menuet probably reflects the original spelling, deriving from the small steps (pas menus) of the dance.

2Fritz Rothschild, Musical Performance in the Times of Mozart and Beethoven (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1961), p. 77.

3Frederick Dorian, The History of Music in Performance (New York: Norton, 1942), p. 125.

4Carol MacClintock, ed., Reading in the History of Music in Performance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), pp. 321-22.

5Quoted in Frederick T. Wessel, The "Affektenlehre" in the Eighteenth Century (Dissertation, Indiana University, 1955), p. 176.

6Dorian, p. 115.

7All English translations are taken from William Mann, The Operas of Mozart (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

8Alfred Einstein, Mozart, His Character, His Work (New York: Oxford University Press, 1945; Hesperides Books, with corrections, 1962), p. 393.

9William Mann, The Operas of Mozart (London, 1977), p. 238.

10Willi Apel, Harvard Dictionary of Music, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1969), p. 73.

11Michael Robinson, Opera Before Mozart (New York: William Morrow, 1966; Apollo Edition, 1967), pp. 62-63.

12James R. Anthony, French Baroque Music, revised ed. (New York: Norton, 1978), p. 87.

13Paul Nettl, The Dance in Classical Music (New York: Philosophical Library, 1963), pp. 3-4.

14Beekman Cannon, Johann Mattheson, Spectator in Music (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1947; repr. Archon Books, 1968), pp. 147-48.

15Johann Mattheson, Cleopatra, reviewed by Rosamond D. Brenner in JAMS XXX, No. 2 (Summer 1977), 334.

16Vocal settings of original minuets by Handel and others were published in contemporary songsheets and anthologies. The fifth edition (1954) of Grove's Dictionary (IV, 56) lists these as "Minuet Songs" published in 1731, although most were issued separately and later versions of some have different words. The sixth edition of Grove gives more details on these little-known minuet songs.

17Quoted in Robinson, p. 109.

18Anna Amalie Abert, "The Operas of Mozart" in The Age of Enlightenment 1745-1790, New Oxford History of Music, Vol. VII (London: Oxford University Press, 1973), p. 114.

19Mann, p. 170.

20Idem, pp. 145, 170.

21Frits Noske, "Social Tensions in 'Le Nozze di Figaro,'" Music and Letters, Vol. 50, No. 1 (1969), p. 60. Reprinted in The Signifier and the Signified (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1977), pp. 18-33.

22Mann, p. 424. For a contrasting view, in which the insertion of arias nos. 24-27 is considered as "a stroke of genius for Da Ponte and Mozart," see John D. Drummond, Opera in Perspective (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1980), pp. 200-201.

23Dorian, p. 109.