In view of the extensiveness of the commentary on Beethoven's music it is perhaps unusual that there exists a short passage in the opening movement of the first "Rasumovsky" Quartet (Op. 59, No. 1) which analysts have either avoided or have dealt with largely as an inexplicable oddity (see Ex. 1).

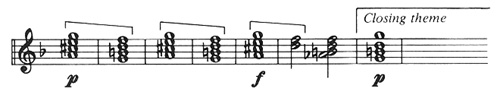

Ex. 1. Exposition: mm. 83-93

The passage, appearing in the exposition (mm. 85-90), development (mm. 144-51), and recapitulation (mm. 337-42), has been variously described as having a "curious see-sawing effect;"1 as being "in mysterious piano, the most haunting passage of all: provocative chords or half chords in slow half notes and in widest spread from high to low, holding us in a sort of limbo of suspense until we regain the familiar ground of the conclusion theme;"2 as representing a "mysterious shadow" which "looks ahead to the bare colouring of the posthumous quartets;"3 and as signifying "cryptic half-note chords, irregular harmonically and very widely spaced; one thinks, oddly, of Webern."4

One question that comes to mind is why Beethoven wrote the passage in the first place. We can come closer to an understanding of its function if we delete it and take note of the effect:

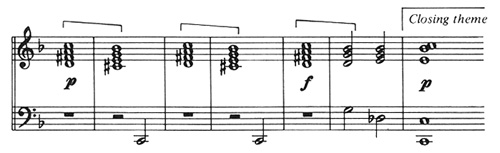

Ex. 2. Exposition: mm. 83-93, deleting mm. 85-90

Here we are struck by the sudden change in the dynamic level, from fortissimo to piano, by the immediate registral drop from G3 to G1, and by the shift from the vigor of the preceding music to the gentleness of the closing theme. In spite of these factors, the harmonic progression is rudimentary, simply tonic-dominant, and it is clear that the intervening passage Beethoven composed does not serve the purpose of modulation. Nonetheless, Beethoven's insert, beginning with the soft dynamic level that marks the subsequent closing theme, itself embodies wide registral shifts. These two aspects, dynamic level and registration, thus serve the dual roles of preparation and buffer.

But the relationship of content to function is at the same time both broader and more complex, for the passage manifests harmonic material common to the movement at large. Kerman, in his book on the quartets, has observed that triads whose bass notes lie a second apart occur frequently in the movement, a harmonic progression related to prominent melodic motion, D falling to C and G to F, perhaps related to the opening two notes of the Russian tune at the start of the finale. In need of refinement, however, is Kerman's conclusion that "the juncture of F-major and G-major triads becomes a familiar sound in this composition,"5 for, in the F-G context, the chord built on G is most often a dominant seventh of F with the fifth in the bass; in other words V of F. Only once in this context does the G support a major triad, and here (m. 39), en route to the second theme in the exposition, a seventh is added. Elsewhere, in the coda (mm. 357-58), the G chord (with seventh) appears in first inversion, following the tonic triad, F, with its third also in the bass. Nevertheless, the point remains that Beethoven frequently enriches the melodic motion, G to F, by harmonic means. When we eliminate the octave displacements and join the half-note chords to form one full chord per measure, we notice at once that the passage itself embodies the kinds of harmonic activity found elsewhere in the movement.

of F. Only once in this context does the G support a major triad, and here (m. 39), en route to the second theme in the exposition, a seventh is added. Elsewhere, in the coda (mm. 357-58), the G chord (with seventh) appears in first inversion, following the tonic triad, F, with its third also in the bass. Nevertheless, the point remains that Beethoven frequently enriches the melodic motion, G to F, by harmonic means. When we eliminate the octave displacements and join the half-note chords to form one full chord per measure, we notice at once that the passage itself embodies the kinds of harmonic activity found elsewhere in the movement.

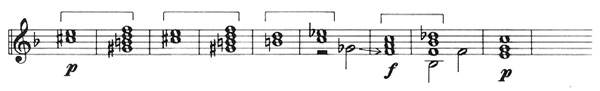

Ex. 3. Exposition: mm. 85-91, reduction

In the exposition the dominant seventh chords a second apart, built on A and G, themselves carry implications that enhance the closing theme immediately following. While the chord on G is the dominant of C Major, the key of the closing material, the chord on A serves as the dominant of the supertonic (D), which itself has a subdominant relationship to the dominant. The first chord in the last measure of the passage confirms the tendency of the chord on A to act in a dominant-seventh capacity. This supertonic sound (without a fifth) is dissolved by the next, and final chord, a diminished seventh which wrenches the music into the closing theme. The coloration on the supertonic thereby contributes to the freshness and warmth of the closing theme, as distinct from its effect when the insert is eliminated.

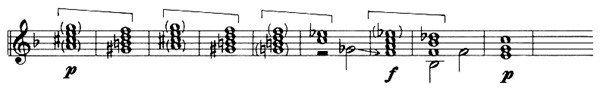

The passage in the recapitulation also functions as a non-modulatory link to the closing material. Here, however, the diminished seventh chord in the second and fourth bars replaces the dominant seventh chord prominent in the exposition:

Ex. 4. Recapitulation: mm. 337-343, reduction

Appearing initially during the passage in the development, the distinctiveness of the diminished chord in the recapitulation is heightened by the cello's unaccompanied low C-natural, a note which prevails over the ambiguity of the diminished sound and provides a strong dominant-tonic progression to facilitate the soon-to-follow victorious statement of the main theme in the high violin, supported for the first time in the movement by the root planted firmly in the cello.

The chords in the development section are preceded and followed by music similar to that which frames the passage in the exposition and recapitulation, even though what follows the link in the development assumes a rather suspended, mysterious quality by virtue of the unusually wide spacing of the unexpected C Major chord in first inversion (see Ex. 5).

Ex. 5. Development: mm. 142-153

Unlike the outer sections of the movement, however, the chords now serve to modulate, a tendency evident even from the initial chord, C-sharp and E, a sound immediately cancelling the E-flat Major triad of the previous bars.6 In fulfilling its modulatory function, sequence becomes the primary device. Following the repetition of the first two measures, the pattern is transposed, with alterations, down one step (without repetition) and then down another step. The G-flat in the sixth measure7 transfers the harmony into the realm of supertonic in B-flat Minor, the dominant of which is heard loud and forceful as the first complete triad in the next measure. The sudden move to the B-flat Minor chord followed by the half-step side-slipping to the first inversion C-Major chord results in a notable Phrygian quality, which, in turn, contributes to the distinctiveness of the subsequent music.8 It would appear that Beethoven eliminated the outer notes of the dominant seventh triad in measures 1, 3, and 5 (compare Ex. 6b, with notes eliminated in parenthesis, to Exx. 3 and 4), so as to increase the fluidity of the modulatory scheme inherent in the passage at this point in the development section:

Ex. 6a. Development: mm. 144-152, reduction

Ex. 6b.

Whether or not we are successful in rationalizing or justifying the presence and function of the passage is one question. At the same time, the passage poses an esthetic problem by virtue of its paradoxical, curiously ambivalent quality. In connection with literature, theater, and Beethoven, Rey Longyear has written of romantic irony as being "subjective in its capricious destruction of illusion and mood, yet objective in representing the author's detachment from his work, over which his sovereign control is best shown by 'an arbitrary playing with it.'"9 For Longyear, the application of romantic irony to Beethoven's music includes "the juxtaposition of the prosaic and the poetic"10 and sudden "surprising tonal shifts"11 as the essential means of interrupting a mood. One of the works Longyear considers is the second movement of the Op. 59, No. 1 Quartet. While he does not mention the first movement, it would appear that the passage which is our concern here qualifies, on the subjective level, as an abrupt, seemingly capricious interruption of the mood, and on the objective level, as an integral harmonic and structural component of the movement at large.

1Joseph de Marliave, Beethoven's Quartets (New York: Oxford University Press, 1928; repr. Dover, 1961), p. 64.

2Daniel Gregory Mason, The Quartets of Beethoven (New York: Oxford University Press, 1947), p. 89.

3Philip Radcliffe, Beethoven's String Quartets (New York: Dutton, 1968), p. 51.

4Joseph Kerman, The Beethoven Quartets (New York: Knopf, 1971), p. 98.

5Ibid., p. 102.

6The E-flat triad is the Neapolitan of D Minor, this key having been established several bars earlier (m. 131). (D Minor seems to be a key Beethoven stresses in the outer sections of the movement as well—during the passage in the exposition as coloration of the dominant of C Major, and at the end, with the D Minor triad preceding the dominant of F, deepening of the melodic motion, D to C.) The C-sharp and E following the Neapolitan thus form the dominant (minus the root) which resolves to the tonic, D and F, a harmonic goal clouded by its conversion into a diminished seventh chord with the addition of the notes G-sharp and B. When the pattern is transposed down a step, the resolution to the tonic is clearer, with the notes C and E-flat sounding during the first half of the measure. The G-flat entering in the second half of the measure shifts the harmony into the supertonic in B-flat Minor. Only with the dominant of this key does a full triad occur, concurrent with the burst into a loud and forceful conclusion. (B-flat is a significant key in the development section at large, in the major mode towards the beginning and in the minor mode during the fughetta towards the end.)

7The G-flat is enharmonically equivalent to F-sharp, the spelling Beethoven would have assigned the note had he been consistent with the previous measures in which the diminished seventh chord is built on G-sharp. Obviously, the G-flat is necessary for the tonicization of B-flat Minor.

8While half-step motion also occurs at the end of the passage in the exposition and recapitulation, only the lower voice, which descends to the root of the dominant, is involved.

9Rey Longyear, "Beethoven and Romantic Irony," The Musical Quarterly LVI, No. 4 (October 1970), 653; also in The Creative World of Beethoven, ed. Paul Henry Lang (New York: Norton, 1971). Longyear borrows the phrase "an arbitrary playing with it" from Alfred E. Lussky, Tieck's Romantic Irony (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1932), p. 29.

10Longyear, p. 655.

11Ibid., p. 656.