In the last years of his life, Johann Sebastian Bach engaged himself in three projects which set forth the intricate laws of counterpoint. The Musical Offering, The Art of the Fugue, and the Goldberg Variations were thus created to exemplify in musical form the technique of what Bach saw as a dying art. A recent discovery of an addendum to the Goldberg Variations, BWV 1087, titled "Fourteen Canons," reveals again Bach's most technical and coincidentally humorous side.

At first glance one would see nothing amusing in the actual music of these canons. The humor is of a very subtle and intellectual kind—an inside joke for contrapuntists. The canons are written in enigmatic notation, a common source of pleasure for the composers of Bach's day because it sets down only the Proposta, or leading voice of the canon, and leaves its completion open to the pursuant, who must find how the melody fits against itself based upon an inscription at the beginning of the canon.

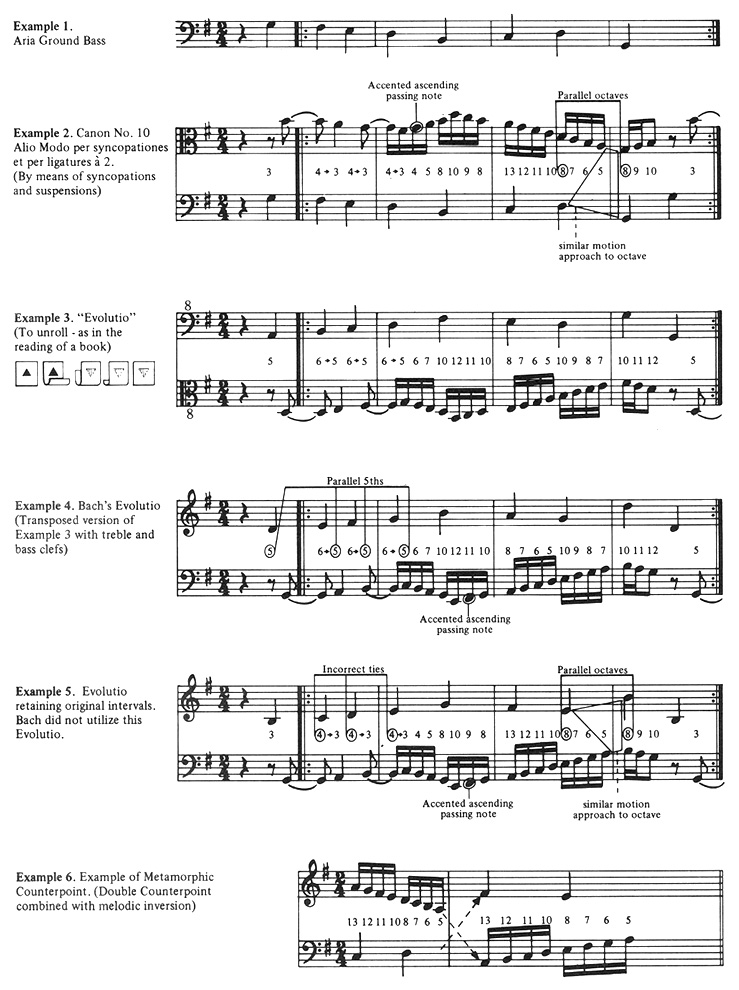

The purpose of these contrapuntal crossword puzzles was not only to provide idle amusement for the experienced fugaphile, but to rigorously develop a composer's awareness and acuity of perception in realizing the possibilities inherent in a musical theme. At times the devices used would manifest themselves as a visual game, as in the crab canon, which could be read from left to right, or from right to left without changing any notes; and the inverted crab canon, which could be read in the same way by turning the page upside down and reading from left to right. Not only is the utmost skill required to compose these mechanical stunts, but also a sense of mischief, for they are rarely "correct" by the academic rules of counterpoint, a fact which also taxes the conscientious composer's aesthetic sense. Ever the mischief-maker, Bach sets himself the task of spinning such web in the Fourteen Canons, from which we shall choose Canon No. 10 (Example 2) to illustrate Bach's sense of fun.

The Canon No. 10 exemplifies a rather obscure type of counterpoint, which the Russian theorist Sergei Ivanovich Taneyev calls "metamorphic" counterpoint. Metamorphic technique merely involves combining double counterpoint with melodic inversion, producing a kind of intervallic double-negative. Thus, inverting the melodic movement of any two counterpointed themes and placing them in double counterpoint at the octave will yield the same harmonic intervals as in the original, as shown by Example 6. Canon No. 10 contains two such themes, the bass theme being the Aria ground (Example 1) upon which Bach counterpoints a second theme utilizing suspensions ("ligatures"). The inscription above the music reads "Evolutio," a Latin term meaning "to unroll, as in the reading of a book." Here Bach is presenting an indeed clever visual game, because if one unrolls the page and holds the music to the light, reading it through the back, the metamorphosis of the canon takes place naturally. Example 3 attempts to show what the canon looks like after undergoing this procedure. (The octave extensions attached to the clefs are needed to put the parts in their proper register. Example 4 shows Bach's transposition of the Evolutio, using now Treble and Bass clefs). Notice that the Evolutio which Bach uses (Example 4) begins with the fifth, whereas the original began with the third. If the original intervals are retained, as in Example 5, by shifting the top voice down a third, six contrapuntal errors manifest themselves as a result. These ineptitudes violate some of the basic rules of the strictest academic counterpoint, and in a piece of such short length and pedantic intention, one would think that these violations be best avoided. Bach does avoid them, if only by avoiding the metamorphosis altogether. What is puzzling is that the Evolutio which Bach chooses contains four errors, so the question remains as to what governs Bach's choice, since both versions contain so many debilitating errors.

To answer this, we face a paradox, and in the middle of this paradox we find Bach the Humorist. To begin, the fact that Bach chooses to use suspensions at all indicates that something is amiss, since all correctly resolving suspensions in the original, when inverted melodically, must "resolve" incorrectly upwards in the metamorphosis. Hence, the two 4-3 suspensions which open the example would become incorrectly resolving ties ("syncopationes") in the hypothetical Evolutio of Example 5. To circumvent this breach of contrapuntal ethics, one must use the Evolutio which begins with the fifth (Example 4). This is the only reasonable solution because the only tie which can resolve correctly upward is the fifth to the sixth since they are both consonances. The only problem here is that we get a perfectly lame sequence of parallel fifths, the worst possible blemish in counterpoint. One can here imagine Bach chuckling under his breath at all the contrapuntists scratching their heads over this enigma. Secondly, the solution of the Evolutio is for all intents and purposes only half contrapuntal. The parallel fifths occupy exactly half of the ground bass theme, and because all parallel octaves and fifths destroy the independence of the parts, it is safe to say that this is hardly counterpoint at all, let alone good counterpoint! And one more interesting quirk remains. In Canon No. 10 there are two errors which exist independent of the blasphemous blunders in the Evolutio (Example 2). All in all, it seems as if Bach doomed this attempt from the beginning.

In essence, then, this is a futile, non-contrapuntal exercise in which Bach irreverently lays bare the truth that complex counterpoint and good counterpoint are not necessarily compatible. The proverbial cardinal sins of the contrapuntist now revealed, perhaps it can be speculated upon whether a joke which needs explaining continues to be amusing.