I. INTRODUCTION

Although much has been written and discussed concerning the pedagogy of music theory, the pedagogy of composition has traditionally been left almost entirely to the individual teacher. Several authors have suggested specific approaches: the importance of improvisation,1 the holistic method,2 the collective experience,3 the heuristic process,4 and student independence from the authority of the pedagogue.5 But the central concern of composition teachers—how can we help students explore the full range of their creative potential—has not been addressed. This article will present a pedagogical philosophy and its practical applications based on the premise that what we need is a more human and artistic relationship between student and teacher, a relationship which necessarily involves consideration of the student as a total creative being. Without this insight, an arid and tenuous relationship develops, leading to a lack of personal involvement and empathy between student and teacher.

Some composers in academic environments have responded to the pressure of being scholars as well as artists by attempting to become just as scientifically research-oriented as their colleagues in the hard sciences. They have invented an elaborate jargon to make their activity not "just" an art, with all its inexplicable sources of inspiration, but a legitimately and totally justifiable "science" divorced from intuition, sensation, and feeling, and one that is conveyed to apprentices by a rigid and rational system of techniques and gadgets. Or, on a more mundane level, composition may be treated as a craft, with total attention being paid to details of the student's orchestration, notation, and consistency within a style. Composers often teach as if nothing more were involved in instruction than the tidying up of a manuscript or the introduction of the student to twentieth-century techniques. These approaches would be considered totally unacceptable in performance pedagogy, where it is assumed that the artist-teacher will discuss the expressive and psychological content of the student's work.

These ineffectual pedagogical methods are far too common in American university and college environments, where there are many good composers but few good composition teachers. This is not surprising: many fine universities and conservatories offer graduate courses in theory or piano pedagogy, including practical experience in the classroom, but a course in the pedagogy of composition is hard to come by. The lack of a formalized pedagogy of composition may in part stem from two basic misconceptions: 1. Composition cannot be taught per se; the student merely needs someone to evaluate the working-out of musical systems and to see that everything is notated correctly. 2. Teaching composition involves little more than the knowledge assimilated in pedagogy of theory, twentieth-century techniques, and music literature courses. These two misconceptions lead to a disastrous product: young composers with Ph.D.'s who write logical, explainable music, replete with sophisticated techniques but lacking artistic integrity because as artists they are immature in the emotional, intuitive, or sensory realms of creative endeavor. In short, there is a preponderance of emphasis on the intellectual side of our artistic training.

As composition teachers, we need to ask ourselves if our efforts to objectify the subject matter of composition are causing the musical work to be considered a separate product, one distinct from its creator. In the lesson, is the piece referred to, but the composer's relationship to the piece ignored? Is the method by which the student has obtained ideas or material considered? Too often the student is expected to get ideas "somehow," without introduction or insight from the teacher regarding the widely different approaches to this stage of the compositional process.

II. DIFFERING APPROACHES TO THE CREATIVE PROCESS:

THINKING, FEELING, SENSATION, AND INTUITION

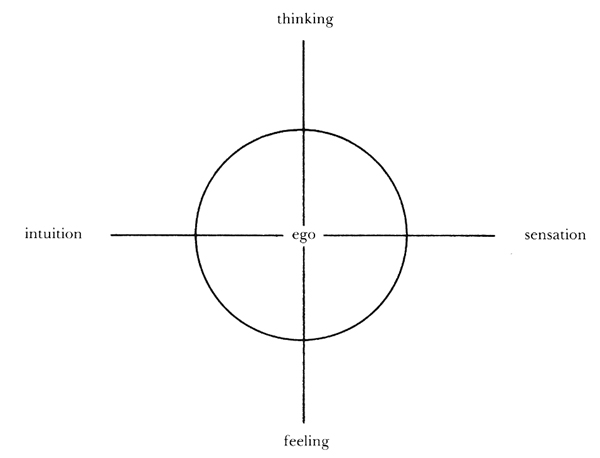

No two composers have exactly the same psychological approach to obtaining ideas or shaping and directing their artistic impulses. However, at least four major types of approaches may be said to exist, with each individual using all four in differing proportions and orders: thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition.6 The noted psychologist Carl Jung related these four approaches to a central entity (the ego) as the opposed quadrants of a circle (Example 1).7

Example 1. Four Approaches to the Creative Process.

In the center is the ego, which ideally selects, intensifies, and diverts by intention and will power, acting as mediator between the various approaches to the creative process.8 The emphases on each of these poles are related in that they can be seen as complementary opposites. The composer, then, uses all four, but will usually show a preference for one creative approach in particular. In addition, the approach diagrammed as opposite to the creative focus is typically the "blind spot" of the composer. For example, a composer who emphasizes thinking is less in touch with the feeling approach—instinctively fearful of or oblivious to this aspect of composition. A similar situation applies to the intuition-sensation dipole. The conscious activity of sense perception precludes the unconscious perception of intuition.9

As applied to composition, these approaches and their varying degrees of emphasis are certainly a determining factor in the development and expression of style. Although all four modes of expression are needed for a balanced compositional process to occur, the emphasis or lack thereof on a particular type of creative expression gives the composer his or her individual profile. In the case of a mature (perhaps, say, a historically important) composer, an imbalance may be present, but all four modes of creative expression have been discovered and developed. In the case of an inexperienced composer, one or more of these approaches often remain totally untapped. In the more extreme cases of imbalance, the young artist may lose touch with his or her work, eventually drifting into apathy, frustration, and ultimate failure. By being aware of these four modes of expression the composition teacher may be able to assist the student to explore the entire spectrum of creativity, and thus fully activate the artistic potential which may otherwise lie dormant and untapped.

Perhaps the easiest approach to understand is "thinking," because, as stated earlier, this mode of creativity has been so strongly emphasized in the attempt to align composition with other "research" and explain it as totally rational.

Total serialization, an archetypal model being Structures by Pierre Boulez, is an example of thinking in complete control. Almost all precompositional and compositional choices were made by the composer from the thinking approach. Certain pieces by Milton Babbitt incorporating combinatorial principles, as well as certain types of computer-generated music, can also be said to be preponderantly thinking-oriented. Typically, the genesis of an over-emphasized thinking-approach piece is an intellectual concept, a technique, device, form, or system, and most decisions are made on the basis of logical, empirical thought systems. I submit that the greatest composers have possessed four highly integrated creative modes of expression, with perhaps a temporary emphasis on a particular approach, but yet never totally ignoring the other three creative standpoints. It can be easily argued, for instance, that Bach's Die Kunst der Fuge emphasizes a thinking mode more than his feeling-oriented Mass in B Minor, but the greatness of both works lies in their incorporation of all four modes of expression, not the total dominance of one to the exclusion of all others. Although feeling, intuition, and perhaps sensation might only get in the way in a performance of Structures, a performance of Die Kunst der Fuge would be utterly meaningless without the other three modes of expression.

Opposite the thinking approach lies feeling. The primitive or so-called "lower" feelings are the gut-level emotions such as jealousy, fear, rage, and lust. The "higher" feelings exercise a refined sense of discernment, such as the appreciation of beauty and feelings of love, displeasure, or other attitudes.10 Both higher and lower aspects come into play in music. Puccini's ability to command the visceral level of feelings in his operas and Ornette Coleman's portrayal of gut-level primal-scream energy in his "free jazz" style of the 1960s are both instances of the more primitive or lower levels of feeling. This is not to say that these works are in any way inferior; such composers have simply taken their primary compositional impulse from basic and universal human emotions. On the other hand, a work such as Britten's opera Death in Venice explores the conflict of a man caught by the lower instinctual emotions that possess him, distorting the higher levels of feelings that involve discernment of aesthetic quality and beauty. The feeling approach is not the depiction of a feeling as much as it is an approximation of the feeling itself. For example, Wagner's revenge leitmotif is not just a depiction of revenge, which could be viewed in a detached manner, but, if successful, revenge itself; the feeling personified.

Typically, the feeling-dominated composers are not distinguished by their complex and clever forms, ingenious compositional devices, or other highly structured systems and approaches. In fact, this aspect of the compositional process may elude all but the most masterful of them, and it can be said to be their blind spot.

The remaining creative dipole, sensation-intuition, is also a complementary pair of opposites. Although both sensation and intuition involve perception, the sensation approach is a conscious perceptual translation of outside stimuli, whereas intuition involves the passive reception of perceptions from the unconscious. Intuition may depend on external stimuli to set the conditions necessary for receiving or translating these unconscious messages. It may also attach meaning to external stimuli after originating in the unconscious, but the senses themselves act as barriers to receiving these unconscious flashes of inspiration known as intuition.11

The sensation composer may take a sensual image or remembrance as the impetus for an entire work, such as Ravel in Jeux d'eaux or Debussy in La mer. Most works of the programmatic cast, like Beethoven's Pastoral Symphony or Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique, fall into this classification.

The sensation may be aural, visual, olfactory, or tactile. Continuum, a work for solo harpsichord by György Ligeti, explores a rapidly undulating sound pattern that changes very slowly, thereby exploring sound itself (in fast/slow motion) and how the sensation of that sound changes. The ultimate in this genre is Stockhausen's Stimmung, which devotes an entire hour to the exploration of the very subtle coloring of a single chord sustained by vocalists.

Intuition, the fourth approach, may manifest itself in several ways. Many composers who work intuitively may merely summon up their proper work atmosphere, keep an open mind, and wait and trust whatever comes to them. Others may incorporate material from dreams, which are personal and collective messages from their unconscious. Mozart is an example of a composer whose ideas simply "came to him" (often in final form) from an intuitive source.

Some composers have employed systems of thought that paradoxically cancel out the empirical process, thereby opening the way to a higher discipline "from above" (universal consciousness, God, etc.) typical of the intuitive approach. Composers who employ aleatory methods often work under the assumption that a seemingly random input of stimuli may somehow open the way to unconscious inspiration of an intuitive nature. Composers such as John Cage, Elliott Schwartz, and even Mozart (in his "Musical Dice Game") have incorporated this intuitive realm into their works. Although the choice of method here is a result of thinking, the modus operandi is designed to defeat the rational process and thereby attune the composer to ideas that originate from without instead of within. From the intuitive approach come the innovative, experimental, improvised, and revolutionary. Learning to trust intuition is a very important aspect of compositional growth.

The order and emphasis of these approaches and the role they play in the pre-compositional and compositional process help to determine each composer's style and method of composition, and should be central to the teaching of composition.

III. PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

The method of application of these concepts depends upon the student's ability, prior experience, and level of advancement. Obviously the application used for the neophyte composer would differ from that used for the more advanced composition student with a particular problem or only in need of "fine tuning."

I have used methods described below when working with high school-aged composers enrolled in the Young Scholars Program in the College of Creative Studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara and undergraduate music majors at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Most of the students in the Young Scholars Program had had early beginnings in music but were just starting to compose for the first time. A few had written music without previous instruction.

For the beginning student, an introduction to these four creative modes of expression, together with assignments that emphasize each approach, can illustrate much about the precompositional process and contribute in a creative way to the individual's self-knowledge. A good introduction to the concept might entail the composition of four very short piano pieces—a project that, with the correct guidance, can easily be completed in a quarter or semester. Each short piece is to be written from the standpoint of one of the four creative approaches.

All four approaches come into play in each creative endeavor, but the standpoint and beginning impetus can vary considerably. After a short introduction to the concept (either in a group situation or individually), in which examples of the results of each approach are played, the student is asked to write a short piano piece emphasizing one of these creative modes of expression.

It is important for the beginning student that the composition teacher provide direction and give sufficient examples of how to go about working from each standpoint. At times an on-the-spot demonstration of how to work from a particular standpoint (actual composition) is helpful, especially if the approach being considered is a blind spot in the student's creative personality.

With an absolute beginner, the teacher has no past evidence of the student's individuality; however, a brief conversation might give some clues as to which approach he or she might tackle first. If no real emphasis can be seen, perhaps sensation is the most approachable mode of expression to begin to explore. One of the best ways to introduce the sensation approach to composition is to work with improvisation. The impetus for such a session can be either verbal or visual. Having the student improvise a piece on a line of poetry or a painting provides a simple starting point for a discussion. For example, the differences between subtleties of evocation and mere sound effects could be discussed and demonstrated.

Also for beginning students, I feel that starting the piece is the most difficult and important task. Therefore I always ask them to write three beginnings of the piece, all completely different answers to the same compositional problem. For instance, if they decide to capture the sensation of rain, one beginning might be "mist with a rainbow," another a "violent thunderstorm," and a third could evoke the sensation of rain in a less direct way (perhaps with certain harmonies). Seeing alternatives and summoning the necessary energy to begin again and again will enrich the final product, which might then incorporate more than one of these potential "beginnings" within the body of the work.

If the initial approach happens to be the young composer's blind spot, the teacher may meet with tremendous resistance from the student, or the student may be faced with an inability to begin or complete the short assignment. As stated earlier, this is because the particular mode of expression is the student's weakest; it is the least developed and most foreign of the four to him or her. If such is the case, rather than discourage the student by insisting beyond reason that he or she do what may be impossible, it is better to switch to the opposite pole, which is usually somewhat more developed. Following that, instead of proceeding directly to the weakest mode of expression, have the student explore one of the "auxiliary" approaches to instill even more confidence. The "auxiliary" approaches are the two found on the axis in the diagram at right angles to the most highly developed mode of expression. By developing these two auxiliary approaches the composer may eventually be able to discover an inkling of the unexplored creative mode.12 Some students may find it impossible to work with all four of these approaches on a conscious level. It is important to remember that the goal is not to change the student's orientation to match the teacher's but rather to introduce the full spectrum of creative potential to the composer.

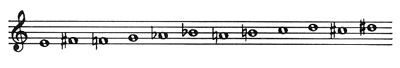

After exploring the sensation mode, I usually introduce thinking as the focus for the second short piano piece assignment. I have found synthetic twelve-tone modes valuable in introducing the student to the thinking emphasis (see Example 2).

Example 2. Twelve-Tone Symmetrical Interval Mode.

One of my beginning students relied almost totally on the feeling aspect of his creative abilities. His music all originated from emotional energies. This person was so out of touch with (and actually afraid of) the thinking approach that he had trouble even beginning to notate ideas correctly. The music had a pleasant quality but was extremely repetitive and lacked both structure and formal integrity. By asking him to create a synthetic repeating-interval twelve-tone mode, I forced him to think about the way he organized his ideas in a formal sense. In his case, using this hitherto undiscovered approach helped him create "novel" yet pleasing sounds, and he was able to use thinking as a mediator for his strongly developed feeling approach to composition. He found it arduous but rewarding, and felt that his work was more satisfying to himself and others.

Twelve-tone symmetrical interval modes (like that in Example 2) may be used with some twelve-tone techniques in a comparatively free manner to create motives and manipulate cells through transposition, retrograde, inversion, and retrograde inversion. All of these techniques can be used precompositionally by the student to discover thinking approaches to form, melodic content, texture, and harmony.

To introduce constructionist concepts of large-scale formal design and proportion, I have students draw, paint, or write (in verbal form) a plan for the entire piece. Again, these beginnings, together with a notebook of sketches (with some employing more intuitive means), are all derived from the central unifying fabric of the mode. It is helpful to the beginner for the instructor to show how chords may be derived in various ways from the mode.

After the thinking approach has been emphasized, I usually direct the student to the feeling emphasis. For this assignment, improvisation is very helpful. Usually I will ask the composer to create (not portray) anger, joy, fear, love, and other feelings in a freely structured improvisation at the piano. If allowed time, the thinkers will intellectualize the project, so a gentle "do it" will dispel this tendency to lapse into a dispassionate portrayal or analysis of the feeling. It is perhaps easiest to start with the more primitive emotions such as rage or fear.

In the case of the feeling assignment, I suggest first that the three beginnings be three different feelings, next that the piece be developed from the strongest of the three. The teacher's task here is to steer the student away from the other approaches if they begin to interfere as the piece takes shape. For example, if the feeling is anger, given form through improvisation on a recognizable motive, thinking has certainly started to take over if the student begins using retrograde inversion or starts turning it into a fugue. It is important at this point to redirect the process into the feeling area.

My fourth short assignment emphasizes the remaining approach, intuition. There are several different pedagogical avenues possible. For some it is difficult to trust the irrational messages from the unconscious, and it may be necessary to use a rational aleatory system (set of rules) that blocks out the thinking function and thereby allows for chance musical events to occur. A stream-of-consciousness approach, in which the natural flow of creative ideas shapes the piece moment by moment, may be used if the student's intuitive function is somewhat developed and the thinking function does not take over and logically dictate every move step by step. Here, too, utilizing improvisation is of benefit, and working quickly also preserves the original conception. Recording the improvisation and trying to write it down as closely as possible might also be helpful to the beginner.

If the student has a pronounced inability to stay with the intuitive approach and consistently relies on one of the other approaches, a possible solution is to suggest an even more aleatory method that prevents logical choices. There are many possible options, such as picking the pitch choices out of a hat or tossing coins; but whatever the procedure, it should introduce the experience of being a passive receptacle, waiting for the intuitive flash to "come from above." Three beginnings in this instance emphasize the added delight of seeing variation that results from chance.

It is important with the beginning student to explain that eventually all four approaches will be used simultaneously when composing, and that this is only an introduction designed to distinguish each creative pole as an important part of the compositional process. As a final project, I have the student write a piece incorporating all four modes of expression. An examination of the sequence and depth of each of the compositional activities that the student chooses provides the basis for further projects designed to broaden the student's creative horizons.

In the case of the more advanced student, the usefulness of these four creative approaches lies more in its value as a diagnostic tool. There are many instances in which a young composer has developed one approach to a rather high degree but somehow has failed to discover the others. In this situation, the introductory assignments—on a larger scale—to the remaining three approaches will still prove useful. More often, however, the student has a complex artistic personality based to some degree on all four modes of expression. In this case, the model's usefulness lies in its ability to point a direction, correct imbalances, reorder precompositional procedures, and overcome writing blocks by tapping undiscovered areas of the creative personality.

I have found these pedagogical methods to be very useful in learning situations involving more advanced students. One very interesting case involved a young composer who had developed a severe writing block. She came to me for several weeks with almost nothing, depressed about her work and her own lack of empathy for what little music she did write. It was easy to see that her entire creative process had been eroded by the thinking approach. She found herself proceeding in "textbook terms," creating invertible motives, extending them, interpolating, augmenting, imitating: dutifully doing everything she thought she should do according to the books. But she felt nothing about her work, except an overwhelming sense of "so what?"—which is exactly how she put it.

My hunch was that this person, in actuality, had a very highly developed feeling side to her creative persona and that she was overcompensating in an effort to accommodate the highly academic intellectual environment surrounding her. To make her work more legitimate she had taken to inventing it on the basis of how well it could be safely explained on an intellectual basis.

To get her unstuck, I gave a demanding assignment: to finish in one night the art song she had been struggling with for weeks. After much consternation she completed it, and liked her product. This first assignment was to get one of the auxiliary approaches, intuition, activated. The stream-of-consciousness approach triggered by the demand to finish the song in one night forced her into a new stance, and silenced her overly critical thinking processes long enough for her to regain some enjoyment from composition.

Next I suggested she write a piece from the feeling standpoint. Ironically, even though I was convinced that this was the composer's strongest ability, she could not proceed. To help, I gave her the programmatic idea of two different characters in an involved emotional relationship. She began an attractive duet for two clarinets, each movement based on a different feeling aspect of human relationship. When she started falling back into her old pattern of over-intellectualizing the process, and therefore losing interest in the project, I redirected her to the feeling approach by asking her to elaborate in the music about the feeling. By developing a personal involvement with the music, through personification of the instruments, she was able to reestablish rapport with her work and express her own most highly developed creative abilities.

Had I worked further with this student, I would have had her write pieces with her two auxiliary approaches, intuition and sensation, in the foreground, as a bridge toward a long-range goal of a less over-compensatory use of thinking. But it was not necessary: she has gone on to develop these aspects of her creative personality in practical experience through her work on film scores, by improvising (intuition) and translating visual images into musical textures (sensation). She has also retained the feeling approach as the primary focal point of her work as she aptly captures the moods and emotions of the characters in films. Thinking is now serving her needs as a means to her end. It helps her calculate the elaborate click track timings necessary for her work, as well as helping in the unification of the motivic organization of her music.

In summary, the pedagogy of composition must address the entire spectrum of a student's creative potential. Four basic creative approaches are utilized by all composers to a different degree of emphasis and order of application. Our academic system frequently over-emphasizes thinking and often ignores feeling, sensation, and intuition. An introduction to these approaches may help beginning composers discover various ways of working, eventually finding their own place in the creative process. At a higher level, being aware of these approaches may be an important pedagogical tool, helping a composition teacher evaluate his or her student's present direction and pointing the way to a finer adjustment and balance of the artist's fullest potential.

1See Wilfried Grühn, "Zum Begriff und zur Praxis der Improvisation," Musik und Bildung 5 (1973):229-32; Günter Hämpel, "Transformation," Musik und Bildung 9 (1977):526-32; and Werner Wittich, "Instrumentalunterricht und Improvisation," Musik und Bildung 5 (1973):242-46.

2See Marco de Natale, "L'analisi musicale: uno sbocco teorico e didattico," Nuova rivista musicale italiana 3 (1969):1105-22.

3See Wolfgang Hufschmidt, "Für Orchester: Die Entstehung einer Gemeinschaftskomposition," Melos/Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 3 (1977):32-34.

4See Otto Laske, "Toward a Theory of Musical Instruction," In Theory Only 2 (1976-77):43-66, which suggests that "the heuristic processes of experts be taught to students of composition, and that what has to be learned by students is, above all, the abstract planning sequence of sub-goals into which composition tasks can be broken down."

5See Pierre Boulez's "A bas les disciples," Musique en jeu 20 (September 1975):29-37.

6Carl Jung, noted psychologist, discovered what he called the "psychological types" in the 1920s. See Carl Jung, Psychological Types, or the Psychology of Individuation, trans. R.C.F. Hull, The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, vol. 6 (New York: Pantheon, 1956). Jung's psychological types, consisting primarily of the extroverted and introverted personality types, have contained within them, as a further subdivision, what he called the "four functions." These functions are feeling, sensation, intuition, and thinking. Although Jung distinguished between extroverted and introverted functions (e.g., introverted sensation), the way in which these functions will be used here as a pedagogical tool will make this further distinction unnecessary. There exist many other fundamental differences between the author's use of terminology and Jung's discoveries.

7See Carl Jung, Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice (New York: Random House, Vintage, 1968), 17.

8Ibid., 15-16.

9Ibid., 16-19.

10Jung has an entirely different meaning for "feeling," which is distinct from what he calls "affect" (ibid., 47-50).

11Ibid., 17-18.

12Ibid., 18-20.