The First Movement of Beethoven's Opus 132 and the Classical Style*

The works of Beethoven's last period, the years 1813-27 broadly defined, have come to occupy a special place in the history of Western music. They are thought to contain some of the most profound utterances of their composer, or for that matter, any composer. And the kind of commentary they elicit has, until recently, been concerned less with a technical explication of compositional procedure than with an impressive assembly of superlatives to register what is, in effect, a confession that these works are beyond analysis. Thus, John William Navin Sullivan, tracing what he termed the composer's "spiritual development," heard in the late works "the greatest of Beethoven's music" and the exploration of "new regions of consciousness," while leaving the necessary explication de texte to his readers' imagination.1 Only with the publication of studies by, among others, Deryck Cooke, Joseph Kerman, Erwin Ratz, Charles Rosen, and Edward T. Cone have technical commentaries been offered as corollaries to critical judgement.2

A critical assessment of late Beethoven has not proved to be an easy task for musicologists. The introspective and experimental character of these works; the preponderance of technique-dominated genres such as fugue and variation; and their improvisatory and other-worldly character: all these have led critics in different directions in their assessments. Two main schools of thought may be discerned. The first consists of those writers who wish to sever completely any bonds that might exist between Beethoven's late style and mainstream Classical style. "It is impossible to describe [Beethoven's late works] as Classical," writes Gerald Abraham.3 But if these works are not Classical, what are they? Romantic? Post-Classical? Neo-Baroque? Neo-Classical? Another writer rules out the possibility of a Classical background to the methods of formal organization found in late Beethoven: "The old academic attempts to analyze the final works in terms of 'expanded' or 'modified' 'sonata form,' 'variation form,' and all the other quaint old formulae of nineteenth-century pedagogy will some day have to be abandoned. Beethoven no longer thinks in these terms, superficially as his procedures may resemble them here and there."4 We may be sympathetic to Ernest Newman's view that each work ought to be looked at within the framework of its internal constraints; but, like Abraham, Newman only tells us what Beethoven's late style is not, not what it is.

In the second school of thought—also the more influential of the two—the emphasis is on the influence of tradition on late Beethoven, not merely that of the recent past—by which I mean the Classical style of Haydn and Mozart—but also that of a more distant past, the styles of Bach and Handel, and even of Palestrina. Maynard Solomon contends that Beethoven "never relinquished his reliance upon Classic structures" while Kerman hears a "persistent retrospective current" in late Beethoven.5 Warren Kirkendale, writing specifically about the Grosse Fuge—a work whose historical allegiances are not in doubt—asserts that "only before the background of tradition can its uniqueness and the personal accomplishment of the composer be determined."6 What Kirkendale fails to do is to return his meticulously documented historical sources to the context of the piece—to tell us, in other words, how the Great Fugue coheres as an individual structure.7

My aim in this article is to assess the status of these conflicting viewpoints as they apply to one of the most remarkable movements from the late quartets, the first of the A Minor, Op. 132, which dates from 1825. Armed with two tools, a Schenkerian notion of levels and Ratner's notion of "topic," I offer a close reading of the "content" (to be explained shortly) of the piece and its internal modes of signification. I wish to show that Beethoven, in this movement, retains both the procedural premises and material sources of the Classical style, that he calls into question one of its fundamental assumptions, and that it is by means of this radical questioning that the limits of the Classical style are, ironically, affirmed. It will also emerge that my concerns are not only to illuminate this particular piece but to present a new analytical method that might aid a critical assessment of the Classical style.

I

That there was such a thing as a Classical style whose chief exponents were Haydn and Mozart is the implicit assumption, rather than the explicit demonstration, of Rosen's book The Classical Style. Preferring analysis to theory, Rosen selects passages from the works of these composers to reveal the senses in which we may speak of a coherent musical language or lingua franca in the late eighteenth century. The emphasis throughout is on the dramatic aspects of the style, and discussion always proceeds with a set of assumed norms, although these norms are rarely stated in abstract form. In the end, it is Rosen's original insights that ring loud and clear, not a definition of the Classical style itself. To see the style in action, he would seem to argue, is more important than listing its normative features.

The historical-theoretical approach, on the other hand, is developed in Leonard Ratner's Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style.8 Drawing on a wide range of treatises and composition manuals of the eighteenth century, Ratner attempts a comprehensive definition of the Classical style, not merely in terms of the prescriptions of theorists but further, and more importantly, from the analytical application of these concepts to numerous compositions by Bach's sons, Haydn, Mozart, Boccherini, Gluck, and others. Ratner thus retains a balance between historical theory and analysis, thereby providing a period view to complement Rosen's contemporary one.

For the purposes of the argument developed later in connection with Opus 132, it will be helpful to isolate and define three aspects of the Classical style, form, harmony, and content, areas whose functions, though by no means exclusive of each other, can be described independently for the sake of analysis.

1. Form. Classic instrumental works fall into a number of standard layouts—binary dance forms, rondo, minuet-and-trio, and so on. These are outer forms capable of sustaining a wide variety of realizations, so that it is much better to think of them as ways of organizing material rather than as rigid schemata or molds into which material is poured. Chief among these is sonata form, an embodiment of a basic rhetorical dialectic, the undermining of an initial premise and its eventual restoration. Although the internal modes of signification within sonata form vary from work to work, the sense behind the gestures, their dramatic potential, remains invariant.

2. Harmony. Harmony, according to Ratner, is the "broadest theatre of action" in Classic music, and it "governs the form of an entire movement through the Classic sense for key."9 Harmonic relationships may be conceptualized on both local and larger levels of structure. Both levels are defined by syntactical procedures whereby basic contrapuntal rules of chord succession—based on conventional dichotomies such as strong-weak, conclusive-inconclusive, stable-unstable—dictate the modi operandi. Thus a I-IV-V-I progression is a normative unit in this style, its internal characteristics being subject to a variety of idiosyncratic representations. Key systems are often referable to the circle of fifths, and movements are always set in closed schemes, however much the authority of the opening premise is undermined.

3. Content. This third category, so described for lack of a better term, refers to the actual materials employed by Classic composers. It attempts to deal with the elements of expression "without which no [Classic] piece was fit to be heard."10 Following the ancient notion of topoi, that is, "the notion of stores of special and commonplace knowledge supposed to exist and presupposed by composers to be in their audience's competence,"11 topics may be defined as "subjects of musical discourse."12 The assumption here is that Classic music is nominally referential, not autonomous. Topics include both types and styles of music current in the eighteenth century, and they provide a unique framework for characterizing the immediate or surface level of Classic music. In Ratner's application, consequently, the topic of "Non più andrai" is a military march, that of the slow movement of the Jupiter a sarabande, that of the first movement of Beethoven's Quartet Op. 59, No.1 the pastoral, that of the opening movement of Haydn's Quartet Op. 77, No.2 a pastoral with polonaise elements, and that of the slow introduction to the Prague Symphony a startling kaleidoscope of some sixteen topics!13 An awareness of these elements of expression is implicit in the best writing on Classic music, but in contrast to form and harmony, the notion of topic has been the least developed in contemporary analytic thinking, partly because of its naturally elusive quality (sometimes mistaken for subjective associationism) and partly because theorists have failed to grasp its explanatory potential.14

II

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of the first movement of Opus 132 is the extreme contrast that dominates the musical surface. Almost everyone who has written about this quartet has had to reckon with this element. According to Walter Riezler,

Beethoven's contrasts, significant and expressive as they were from the beginning, have now (in the late works) acquired an altogether unparalleled profundity. Movements are juxtaposed in seeming incompatibility—in sharper contrast than ever before; and there are "surprises" of astounding magnitude. . . . Not only this, but there are even whole movements in which contrasts prevail without interruption, such as the first of Op. 132, in the first forty bars of which . . . there are continual changes of mood—contrasts even occurring simultaneously—without the homogeneity of construction, which in spite of all is very strict, being not in the least impaired.15

Riezler thus senses not just the threat to coherence implicit in such contrasts but also the pull of a background structure in which these contrasts are regularized.

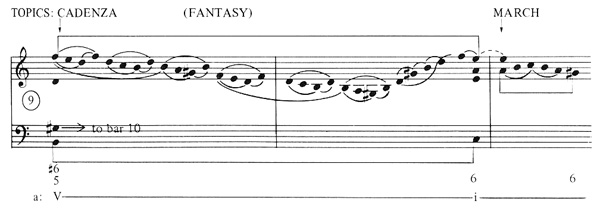

Let us begin by isolating these contrasts within a diachronic framework. (From this point on, the reader will need to have access to a score of the movement in order to follow my argument.) The slow and regular half-note figuration that dominates the first eight bars is followed, or rather interrupted, by a rapid sixteenth-note figure in the first violin (mm. 9-10). Then, with the emergence of what appears to be a coherent musical idea—the dotted figure in m. 11 (cello)—the music seems to be on its way, but only for eight bars, for midway through m. 18 another erratic change occurs, arresting the motion in the manner of mm. 9-10, and leading not to a relatively stable passage as before but to a full Adagio bar (21), a recall of the affect of the opening bars. This, in turn, gives way in m. 22 to the sixteenth-note idea, and then to the dotted figure again in m. 23. On this level of structure alone there is so much change, so much contrast, so much instability; and these are only the first twenty-three bars.

Consider, too, mm. 74-110. Over an augmented and transposed version of the opening material the dotted idea emerges, is developed for a while, and is then followed by what is perhaps the most violent contrast in the entire movement: m. 92. Here, a seemingly new thematic idea (it has superficial affinities with the dotted figure) generates a brief imitative passage. This passage is, however, cut off in mid-stream at m. 103, where the four-note idea from the opening bars returns in yet another transposition.

We need not develop this blow-by-blow account of the entire movement in order to establish the phenomenological validity of contrast. Faced with such an unstable musical surface, contemporary analysis (especially that of the neo-Schenkerian variety) invokes the neutral notion of design to account for the changes of texture and figuration.16 Design is seen as differential only of the musical surface, and is therefore dispensed with as soon as the search for structural processes begins. Yet the variables that generate this particular musical surface are not value-free, but laden with signification. They are semiotic objects drawn from the stylistic code of eighteenth-century music. It is here that the notion of topic can help us come to terms with these elements of expression. By using a set of historically fixed labels drawn from eighteenth-century theory, we may assign value to these elements of design as follows: The opening eight bars suggest learned style (or strict style or bound style), which is a topical class signifying "imitation, fugal or canonic, and contrapuntal composition, generally."17 The temporal unit is alla breve and the whole passage is imbued with a sense of fantasy. Mm. 9-10 suggest, in their improvisatory, virtuosic, and unmeasured manner, a cadenza, while the dotted-note idea initiated by the cello in m. 11 is clearly a reference to march. There is something odd about this march, however, for it is missing a crucial downbeat. This is, in fact, a "defective" march; the "ideal march" does not occur until the end of the movement.18 We hear hints of the learned style in the imitation in mm. 15-17, while the passage in mm. 18-19 describes a fanfare, in addition to which, given its disposition in the context, it evokes the mid-eighteenth-century sensibility style. The cadenza returns in mm. 21-22, followed by the march in m. 23, where it begins to establish itself as the main topic of the movement. But perhaps most striking of all is the new topic exposed in m. 40, which has obvious affinities with the dance gavotte, a gavotte in learned style. Finally, with the arrival of the second key, an aria emerges, complete with an introductory vamp and a near-heterophonic presentation. From this point onwards no new topics are introduced—with the exception of the brilliant style, which serves to provide an appropriate flourish for the end of the movement. Table 1 shows the topical content of the entire movement in paradigmatic layout.

Table 1: Succession of Topics in Beethoven's Opus 132, First Movement

| LEARNED STYLE |

ALLA BREVE |

FANTASY |

CADENZA |

MARCH |

SENSIBILITY |

GAVOTTE |

ARIA |

BRILLIANT STYLE |

| 1-8 | 1-8 | 1-8 | 9-10 | 11 + | 18-20 | |||

| 21-22 | 23 + | |||||||

| 25-28 | 28-29 | |||||||

| 30 + | ||||||||

| 40-44 | 40 + | |||||||

| 48 + | ||||||||

| 60 + | 60 + | |||||||

| 67-74 | ||||||||

| 75-91 | 75-91 | |||||||

| 92-102 | ||||||||

| 103-106 | ||||||||

| 107 + | 107 + | |||||||

| 119 + | ||||||||

| 121 + | ||||||||

| 125 + | ||||||||

| 129 + | ||||||||

| 131-32 | 134 + | |||||||

| 151-54 | 151 + | 159 + | ||||||

| 176 + | 176 + | |||||||

| 182 + | ||||||||

| 193 + | 195 | 212 | ||||||

| 214-17 | 214 + | |||||||

| 223 + | ||||||||

| 232 | 236 | |||||||

| 247 | 247 + | |||||||

| 254-64 | 254 + |

There are two important conclusions to be drawn from this description. First of all, the piece is nominally referential in the manner of earlier Classic music. These topics are culled from a larger—potentially infinite—referential pool of eighteenth-century stylistic signifiers, the same pool from which Mozart drew for his String Quintet, K. 614, and the Prague Symphony, K. 504; Haydn for the Opus 64 Quartets; and Beethoven for the Missa Solemnis—to name only those works in which topical interplay forms a central part of the musical discourse. It is hard, therefore, to support the claim that the style of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven "produced the first great paradigms of a wholly autonomous music."19 Music saturated with topical references can hardly be described as autonomous. Second, because the mode of presentation of these topics is clearly one of understatement, they assume much importance in determining the character of the piece. Their behavior thus points to the elusive dimension of meaning or signification and enables us to construct a plot for this movement, a compositional plot, not an analytical plot. What sort of referential scenario is painted by this particular succession of topics? Why is a solemn motet for strings infused with fantasy elements, interrupted by erratic outbursts in the form of virtuoso display, followed by dance, and then by an operatic character?

The claim that the surface of Beethoven's music is not value-free stands in direct opposition to the Schenkerian view. Indeed, Schenker himself warned against such an enterprise in a famous statement:

A composition presents itself to the observer or performer as foreground. This foreground is so to speak its present. . . . It is . . . difficult for the student or performer to grasp the "present" of a composition if he does not include at the same time a knowledge of the background. Just as the demands of the day toss him to and fro, so does the foreground of a composition pull at him. Every change of sound and of figuration, every chromatic shift, every neighbor-note signifies something new to him. Each novelty leads him further away from the coherence which derives from the background.20

The irreverent response to Schenker's statement would be to say that we as listeners enjoy being blown to and fro by the activity in the foreground, and that an experience rooted in "immediate apprehension"21 is equal to the task of making sense of this movement. But Schenker's point is not that we discount the foreground—which is the impression one receives from the writings of some of his disciples—but rather that we understand the foreground through the background. In terms of the reading of the quartet presented so far, then, we will need to acknowledge the inadequacy of topic as an ontological sign, and to replace that with Ferdinand de Saussure's more all-encompassing arbitrary sign,22 for even those listeners who are sympathetic to the referential implications of topical material will agree that the individual gestures derive their importance less from their paradigmatic or associative properties than from their syntagmatic or temporal ones. In other words, it is not the marches, gavottes, learned styles, and fanfares that matter, but how their conjunction is logically executed in this movement. For if the relationship between phenomena determines their nature, not any intrinsic aspect of the phenomena themselves, then it is to the domain of absolute diachrony that we must turn.23

III

The responsibility for mapping out a logical trajectory falls directly on the domains of form and harmony, the two other categories whose normative procedures I outlined earlier. I shall now show that there is an immediately accessible logic at work in these domains. In other words, the contrasts noted earlier within the syntagmatic chain disappear as soon as we look at harmonic syntax. Despite the formal unorthodoxy of this movement, commentators have persisted in identifying an underlying sonata form. At least three versions of the form have been proposed:

Version 1

Bars:Exp.

1-74Dev.

75-102Recap. 1

103-92Recap. 2

193-end.Version 2

Bars:Exp. 1

1-102Exp. 2

103-92Recap.

193-end.Version 3

Bars:Exp.

1-74Dev.

75-102Recap.

103-92Coda

193-end.

The divergences in the reading of the formal layout arise out of certain representations Beethoven makes towards sonata form, representations that are, however, never normatively enacted. There is, first of all, an "Exposition" that contains two key areas, A minor and F major, each with a profile theme or set of themes. The same premises are presented in the next section, "Development," only this time at a different transpositional level: E minor replaces A minor, and C major replaces F major. Finally both sets of material are reconciled in the home key of A.

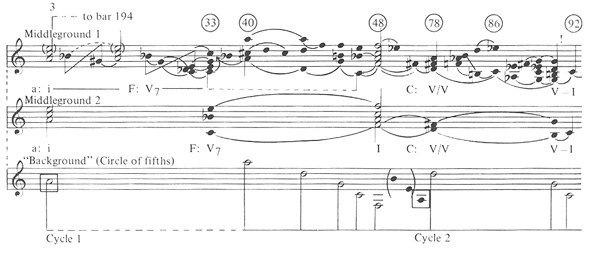

The question of two-expositions-versus-one-development, two-developments-versus-one-exposition, or one-exposition-versus-two-recapitulations need not detain us here simply because the issue will never be settled. But if we think of sonata form as a signifying model, and recall that its harmonic obligations were most fundamental during this period, then the logic of Beethoven's formal strategy is at once evident. There are, in other words, a statement of contrasting premises, a prolongation of this conflict, and its resolution. It is therefore unimportant how one chooses to label the individual sections as long as one grasps the logic of tonal relations. In the analytical chart given as Example 1, I have provided an abstract of the tonal-harmonic structure of the entire movement in the form of a modified voice-leading graph.24 The three lines, Middleground 1, Middleground 2, and Background, represent three distinct but related levels of structural procedure. In Middleground 2, only the major points of articulation are included together with one or two significant transitions. The graph shows that a large-scale progression from tonic to submediant major, first presented on the triads of a and F, is repeated on the triads of e and C and finally on the triads of a and A. What is noticeable here is the high degree of invariance between members of the controlling triads: a and F, like e and C, may be said to display maximum intersection with respect to pitch class within the diatonic triadic universe.

Example 1. Harmonic coherence in Beethoven, Op. 132/I

A coherent background structure need not guarantee a coherent middleground, but in this movement, the same persuasive logic governs the succession of sonorities on both levels of structure. Middleground 1 shows how the contents of Middleground 2 are prolonged by means of familiar modi operandi: neighbor-note motions in both diatonic and chromatic forms, unfoldings, arpeggiations, and tonicizations of various scale steps. Rather than embark on a detailed explication of technical procedures enshrined in this graph, I would suggest that the reader play through the graph at the piano in order to experience not only the logic, but the conjunction in the harmonic syntax. The smoothness and evenness of that reduction are striking, and present a most remarkable contrast to the near-disjunction that characterizes the musical surface. And if there are further doubts about this conjunction, one might look even deeper into the background (line 3 of Example 1) and observe how a familiar Classical construct, the diatonic circle of fifths, controls the harmonic process of the movement.25 Beginning with the center A, the piece travels through five cycles of the circle. All seven possible points occur, although each cycle is "defective." Specifically, three, then one, then four, then two, and then two steps are omitted from the respective cycles. Although Beethoven, here as elsewhere, does not deploy the cycle mechanistically, he provides us with a statistically significant unfolding of its elements to guarantee the coherence of both the local and large-scale tonal progression. Subotnik's statement that "of all the musical systems in Europe, eighteenth-century tonality is constituted of the most readily 'generalized' relationships"26 is borne out by even this movement, composed, let us not forget, in the third decade of the nineteenth century.

IV

We are left with a highly interesting compositional situation, one in which a varied, maximally contrasted, even disjunct surface interacts with a continuous, minimally contrasted background. I would like to suggest that it is in the relationship between these two domains that the secret of the movement lies. And that relationship, as I shall demonstrate presently, is one of disjunction. As a general rule and in perfect consistency with Beethoven's earlier music, changes in topic are used to highlight important harmonic-structural events. The converse of this normative relationship is also generally true for Mozart, Haydn, and early Beethoven, but not for late Beethoven. In other words, while important harmonic-structural events may be signified by topical changes, the latter do not necessarily signify structural events. It is this radical overthrow of the signifying function of topics, the displacement of the one-to-one correspondence between topic and harmony, that constitutes the critical feature of this movement.

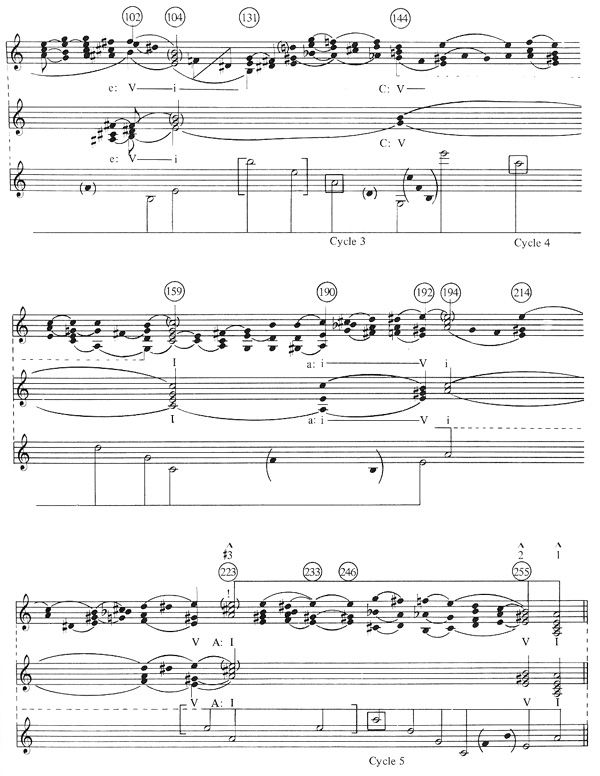

Five separate examples, given in voice-leading reduction as Examples 2a, 2b, 2c, 2d, and 2e (the case of 2e differs from the others), will serve to illustrate this feature of the movement.

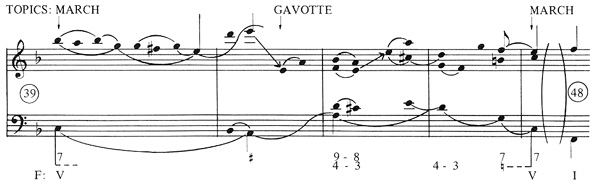

Example 2a (mm. 9-11). Because of the relative neutrality of the alla breve topic, the resultant sonorities in the first eight bars are brought into greater prominence; harmony, you might say, is foregrounded in this passage. Now, the harmonic orientation is clearly towards the dominant of A minor; this sonority is intensified in m. 9 in the form of a diminished-seventh chord presented simultaneously on the downbeat of the bar and successively in the first violin cadenza. It is not until the fourth beat of m. 10 that this prolonged dominant resolves to the tonic, but what a resolution! The tonic is in first inversion, it occurs on the weakest beat of the bar, and it is marked piano. Surely the weight of the extensive dominant prolongation is much too great to be absorbed, let alone neutralized, by this most understated of resolutions. The overall progression of the phrase, then, although describable as a dominant-tonic succession, offers only a partial resolution of V; what it does, in fact, is to challenge the normative rhetorical disposition of a V-I progression. Note that it is only after this partial completion of the V-I progression that the principal topic of the movement, the march, is exposed. The structural-harmonic process is completed prior to the emergence of the topic. In other words, the topic is exposed at a subsequent point in the structural-harmonic process, or, stated differently, the points of topical and harmonic articulation are displaced from each other.

Example 2a. Interaction of topic and harmony in Beethoven, Op. 132/I

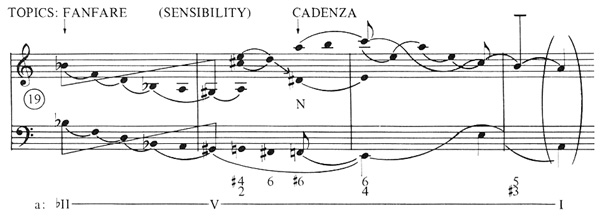

Example 2b (mm. 19-22). In this passage, the outbursts of sensibility function as space-filling material in the approach to the structural dominant in mm. 21-22. By the terms of the fixed harmonic hierarchy that we have invoked throughout this paper, the essential harmony of the passage,  -V-(I) reveals an increase in the harmonic-functional status of each chord. Note, however, that the fanfare occurs on the first of these chords, the Neapolitan. And although it is not unusual in Classic music to hint at the later use of material in this way—the Neapolitan chord obviously prepares the approaching modulation to F major—the topical event acquires special significance in this context first because of its durational prominence and second because of the special affinities between fanfare and the more prominent march. Here, too, the individual hierarchies of topic and harmony do not necessarily function complementarily.

-V-(I) reveals an increase in the harmonic-functional status of each chord. Note, however, that the fanfare occurs on the first of these chords, the Neapolitan. And although it is not unusual in Classic music to hint at the later use of material in this way—the Neapolitan chord obviously prepares the approaching modulation to F major—the topical event acquires special significance in this context first because of its durational prominence and second because of the special affinities between fanfare and the more prominent march. Here, too, the individual hierarchies of topic and harmony do not necessarily function complementarily.

Example 2b. Interaction of topic and harmony in Beethoven, Op. 132/I

Example 2c (mm. 39-48). By this point in the movement the preparation for the second key area is well under way; it only remains for the new key to acquire a profile theme. Then, beginning in m. 39, the cello C initiates a dominant prolongation (the details of which are shown in the example). The gavotte is thus introduced within the unfolding of a harmonic process, rather than at its beginning or end, the more traditional points of articulation. Like the march and fanfare, the gavotte occurs at a structurally subsidiary point.

Example 2c. Interaction of topic and harmony in Beethoven, Op. 132/I

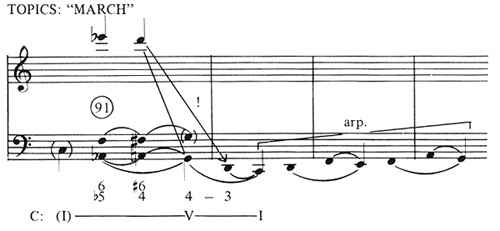

Example 2d (mm. 91-94). In this passage the harmonic resolution from G to C is handled in a quite remarkable way. The topical unfolding assumes primacy while the harmonic process is, as it were, demoted in significance. In other words, the listener accepts as a matter of course an implicit V-I progression (note especially how the high D in violin 1 is resolved four octaves lower!) while being treated to the march-like idea. Topic is not displaced from harmony as such; rather, the relationship between the two domains is inverted from earlier Classical practice.

Example 2d. Interaction of topic and harmony in Beethoven, Op. 132/I

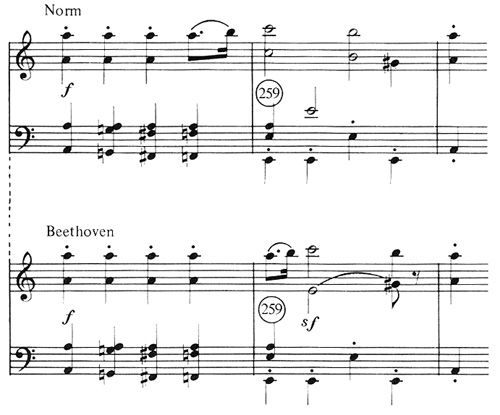

Example 2e (mm. 258-260). The structural tension between the two domains is perhaps most violent at the end of the movement, specifically in the last eleven bars of the piece. Prior to this, closure has been signalled by means of a number of representations towards the tonic. Then in mm. 254-257 we hear a passage that functions, on the one hand, as harmonic parenthesis—we could easily dispense with these four bars as far as syntactic necessity is concerned and go directly from 253 to 258—but on the other hand as a gestural intensification of the sense of an ending. This leads to an extraordinary moment, the downbeat of bar 258, where for the first time the march acquires its crucial downbeat, thereby supplying the essential (and defining) component of the most prominent sign in the movement. This, in fact, is the ideal march. But that is not the whole story, for while thus resolving a tension with a long history, Beethoven undercuts this resolution by means of a rhythmic figure that shifts the accents of the dotted figure in the march (see Example 2e, where I have contrasted a normal articulation of bars 259 and 261 with Beethoven's). The effect of this is to challenge the very sense of closure achieved by the arrival of the ideal march. Kerman's remark that there is "no very determined conclusion"27 to this movement, although contradicted by the outward closural gestures of these last eleven bars, is offered some support by the present reading, which sees the sign functions in conflict, not in synchrony.

Example 2e. Interaction of topic and harmony in Beethoven. Op. 132/I

To sum up: I have argued that the surface of this movement may be heard with reference to the code of stylistic signifiers or topics found in earlier Classic music; that the resulting gestural syntax could itself provide a framework for understanding not just the surface paradigmatic associations but also the syntagmatic properties that stem from reading topics as ontological signs; that stripped of this surface, the formal and tonal-harmonic processes reveal a persuasive operational logic whose coordinates are locatable within the normative Classical style; and finally that there is a consistent lack of synchronicity between surface and background, and that it is this dissonance between the domains that gives the piece its unique character.

One ought to guard against undue generalization stemming from an analysis of a single movement, especially when the subject is as delicate and multifaceted as Beethoven's late style. But at the same time, it would be a pity not to place the results of this analysis in the context of recent attempts to come to terms with late Beethoven. First, it is clearly an exaggeration (if not an error) to sever completely the bond between late Beethoven and mainstream Classical style.28 In fact, the opposite is true. Second, the extent of the analysis should not be the detailing of sources, both procedural and material, from earlier music. This is the limitation of Kirkendale's study of the Grosse Fuge and Sieghard Brandenburg's of the "Heiliger Dankgesang" from this Quartet.29 As my description of the topical process has shown, material sources, once identified, need to be returned to their proper context so that we can understand the logic—or lack of logic—that governs their actual compositional disposition. Third, there is no evidence here of a double perspective. When Glauert writes that "the revolutionary aspect of the late works was their insistence on the right to forge their own relationship to established procedures, from a position no longer within, but outside the sphere of classical norms,"30 I could not disagree more. "Forge their own relationship to established procedures" they certainly did, but the position is squarely within the sphere of classical norms, not outside of it. Fourth and finally, there is no "reconciliation of contrasts" as Brodbeck and Platoff have argued in connection with Opus 130.31 Could it not be that Beethoven here exhorts us to live by this conflict between the domains? Or, to modify a formulation of Adorno's, that the late style is concerned with the irreconcilability of dialectical opposites (in contrast to their reconcilability in the second-style period)?32 Could it not be that the analytically-perceived dissonance thereby becomes a conceptual consonance? However we resolve these questions, it is clear that this is the music of an extraordinarily forward-looking composer whose stylistic premises are rooted in the Classical style.

*A version of this paper was read at the joint meeting of the Northern California and Pacific Southwest Chapters of the American Musicological Society, Santa Cruz, April 1982, and subsequently at the Mid-Atlantic Chapter meeting, West Chester, April 1983. The present version owes much to the comments and criticisms of Laurence Dreyfus. It is drawn from a larger study in progress, Semiotics and the Interpretation of Classic Music

1J.W.N. Sullivan, Beethoven: His Spiritual Development (New York: Random House, Vintage Books, 1927), 148-49.

2Deryck Cooke, "The Unity of Beethoven's Late Quartets," The Music Review 24 (1963):30-49; Joseph Kerman, The Beethoven Quartets (New York: Norton, 1966); Erwin Ratz, Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre (Wien: Universal Edition, 1951); Charles Rosen, The Classical Style (London: Faber and Faber, 1971); Edward T. Cone, "Beethoven's Experiments in Composition: The Late Bagatelles," in Beethoven Studies 2, ed. Alan Tyson (London: Oxford University Press), 84-105.

3Gerald Abraham, ed., The Age of Beethoven, New Oxford History of Music, vol. 7 (London: Oxford University Press, 1982), vi.

4Ernest Newman, "Beethoven: The Last Phase," in Testament of Music (London: Putnam, 1962), 250.

5Maynard Solomon, Beethoven (New York: Schirmer Books, 1977), 294-95; Joseph Kerman and Alan Tyson, The New Grove Beethoven (New York: Norton, 1980), 125.

6Warren Kirkendale, "The 'Great Fugue' Op. 133: Beethoven's 'Art of the Fugue'," Acta Musicologica 35 (1963):14-24.

7There is a third, relatively less important, school of thought, which, failing to appreciate the vitality of the aforementioned critical dichotomy, offers a middle-of-the-road view of Beethoven as part Classic and part Romantic. Thus Amanda Glauert, writing about the C-Sharp Minor Quartet, Op. 131, isolates a "double perspective," an alluring, but ultimately misleading proposition that threatens to drown a healthy debate in the deadly seas of compromise. No bona fide synthesis results from Glauert's formulation of a "double perspective." ("The Double Perspective in Beethoven's Opus 131," Nineteenth Century Music 4 [1980-81]:149-62.)

8Leonard G. Ratner, Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style (New York: Schirmer Books, 1980).

9Ratner, Classic Music, 48.

10Ratner, Classic Music, 1.

11Seymour Chatman, "How Do We Establish New Codes of Verisimilitude?", in The Sign in Music and Literature, ed. Wendy Steiner (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1978), 26.

12Ratner, Classic Music, 9.

13Ratner, Classic Music, 12, 19, 21, 104-5.

14But see Wye Jamison Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1983), which should be read in conjunction with Charles Ford's review in Music Analysis 5 (1986):108-18.

15Walter Riezler, Beethoven, trans. G.D.H. Pidcock (London: Forrester, 1938), 235.

16See, for example, John Rothgeb, "Design as a Key to Structure in Tonal Music," in Readings in Schenker Analysis and Other Approaches, ed. Maury Yeston (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 72-93, and Joel Lester, "Articulation of Tonal Structures as a Criterion for Analytic Choices," Music Theory Spectrum 1 (1979):67-79.

17Ratner, Classic Music, 23.

18I have borrowed the notions of "defective" and "ideal" from Laurence Dreyfus's discussion of Bach's ritornello structure; see his "J.S. Bach's Concerto Ritornellos and the Question of Invention," Musical Quarterly 71 (1985):327-58.

It is perhaps worth mentioning that the composition of this march gave Beethoven a fair amount of trouble, as may be seen in the sketches for this movement published by Gustav Nottebohm. And the trouble arose precisely in the matter of metrical structure—where to locate the downbeat of the march. See Paul Mies, Beethoven's Sketches: An Analysis of His Style Based on a Study of His Sketchbooks (London: Oxford University Press, 1929), 15.

19Rose Rosengard Subotnik, "The Cultural Message of Musical Semiology: Some Thoughts on Music, Language, and Criticism since the Enlightenment," Critical Inquiry 4 (1978):747.

20Heinrich Schenker, "Organic Structure in Sonata Form," trans. Orin Grossman, in Readings in Schenker Analysis, 41.

21Edward T. Cone's term. See his Musical Form and Musical Performance (New York: Norton, 1968), 89.

22For an explanation of this and other semiotic terms used throughout this study, see Terence Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977).

23Here I abandon the line of discussion concerning topics although, as I shall argue in chapters 3 and 4 of Semiotics and the Interpretation of Classic Music, the analysis can be pursued further until one arrives at a background level. Topics, in other words, comprise a self-sufficient and self-regulating analytical framework. The procedure involves first isolating the various dimensions that define each topic and finding out what is occurrent as opposed to non-occurrent. In this movement, for example, rhythm and meter are the obvious choices, and the succession of topics shows that there is a gradual shift from metric instability to metric stability. Thus the learned style at the beginning of the piece defines a pulse, not a rhythm. The cadenza then erases this pulse. The march, though inherently rhythmic, is presented without its crucial downbeat. The arrival of the gavotte reinforces this shift towards metric regularity, a condition that is fully established with the arrival of the aria. A process of destabilization begins soon after the aria, and from then on we experience various dynamic transitions to and from points of metric regularity. This forms a kind of subtext for the movement. The background of this movement as defined by the topical process consists, therefore, not of a pitch-defined Ursatz, but rather of a rhythmically-defined functional stability that moves in and out of subsidiary levels of instability. One therefore does not impose a dimensional hierarchy on the piece, but approaches the idea of background metaphorically.

24In this graph I use a form of the by now standard hierarchic notation stemming from Schenker.

25This graph assumes octave equivalence and represents each cycle by stemmed white notes in descending order to reflect falling fifths. Unstemmed black note-heads in brackets denote missing steps, while notes in square brackets denote repetition within a single cycle.

26Subotnik, "The Cultural Message of Musical Semiology," 752.

27Kerman, The Beethoven Quartets, 249.

28Compare the views of Abraham and Newman cited above, notes 3 and 4.

29Kirkendale, "The Great Fugue"; Sieghard Brandenburg, "The Historical Background to the 'Heiliger Dankgesang' in Beethoven's A Minor Quartet," in Beethoven Studies 3, ed. Alan Tyson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 161-91.

30Glauert, "The Double Perspective," 116.

31David L. Brodbeck and John Platoff, "Dissociation and Integration: the First Movement of Beethoven's Opus 130," Nineteenth Century Music 7 (1983):149-62.

32Rose Rosengard Subotnik, "Adorno's Diagnosis of Beethoven's Late Style: Early Symptom of a Fatal Condition," Journal of the American Musicological Society 29 (1976):249.