The supremacy of Roman numerals in shaping tonal music analyses has eroded considerably in recent decades. Though more cumbersome, the graphic techniques of Schenker and his followers have taken hold in the minds of many analysts. A new conception of harmony has emerged, and linear factors are now much better understood and more frequently recognized. The acknowledgment that some chords are dependent upon others and serve in the role of connecting or embellishing has created a sense of perspective to which the more or less one-dimensional harmonic succession of earlier analyses has paled.

The factors which contributed to an excessively vertical orientation towards tonal analysis also fostered the widespread assumption that the intensely chromatic writing of the nineteenth century could, or should, be understood in terms of harmonic progression.1 Yet recent developments in our field strongly suggest that many facets of chromaticism may be related less to the domain of harmony than to a proliferation of linear embellishment.2 The analyst, by exploring various levels of structure and their interaction, should now be in a position to assess the role of harmony in this repertory more accurately and to reveal other compositional devices that, though hitherto little understood or discussed, can now be recognized as vital components of a comprehensive analytical perspective.

Scrutinized by Wagner, rejected by the mature Schenker, maligned by some modern commentators, the music of Liszt is of critical importance in the careful reassessment of chromatic practice. Five excerpts from his works follow. In each case the analysis presented avoids the sort of Roman-numeral saturation which the rapid succession of chords within the passage might seem to justify. These samples, if successful in revealing the importance of structural levels to our perception of musical events, may serve as models for the creation of a fresh and penetrating analytical outlook for Liszt's music and for works by other composers of his era.

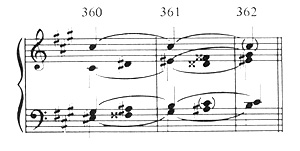

Every analyst, regardless of his perspective, utilizes some notion of hierarchy. In Example 1, from the Sonata in B Minor, no one would deny that the  on beat 2 of measure 360 is dependent upon the

on beat 2 of measure 360 is dependent upon the  which follows it.

which follows it.

Example 1. Sonata in B Minor

Terms such as "incomplete upper neighbor" and "appoggiatura" have been adopted to describe this situation. Similarly the  on beat 3 of measure 361 is functioning as an upper neighbor. In this case three levels of hierarchy are perceptible: prolongation of the pitch

on beat 3 of measure 361 is functioning as an upper neighbor. In this case three levels of hierarchy are perceptible: prolongation of the pitch  ; embellishment of

; embellishment of  through its upper neighbor

through its upper neighbor  ; and connection of the

; and connection of the  and its neighbor

and its neighbor  with the chromatic passing note Cx. Only by recognizing such relationships can a listener begin to penetrate more deeply to the level of harmonic activity. For example, the first half of measure 361 represents the dominant harmony in the key of

with the chromatic passing note Cx. Only by recognizing such relationships can a listener begin to penetrate more deeply to the level of harmonic activity. For example, the first half of measure 361 represents the dominant harmony in the key of  despite the fact that the chromatic passing motion

despite the fact that the chromatic passing motion  -Cx-

-Cx- is under way in the soprano before the leading tone

is under way in the soprano before the leading tone  arrives below it.

arrives below it.

The reduction shown in Example 2 is useful in revealing the basic contour of the passage. Doublings are omitted, so-called "non-harmonic" tones eliminated. Yet does what remains in Example 2 constitute a "harmonic" progression? Thinking in terms of  major (the tonic of measure 363), does V proceed to VI in measure 360? Does the diminished-seventh chord in measure 361 fulfill a harmonic functioneither with Liszt's spelling (Fx,

major (the tonic of measure 363), does V proceed to VI in measure 360? Does the diminished-seventh chord in measure 361 fulfill a harmonic functioneither with Liszt's spelling (Fx,  ,

,  , E) or the enharmonic respelling of Example 2 (Dx, Fx,

, E) or the enharmonic respelling of Example 2 (Dx, Fx,  ,

,  )?

)?

Example 2.

Certainly Roman numerals could be concocted for this succession of chords:

Major: V VI V xVI V

Major: V VI V xVI V

Yet the slurs in Example 2 hint at a much different explanation for the passage. In this alternative perspective,  in measure 360 functions not as the root of a submediant harmony but as a passing note connecting the

in measure 360 functions not as the root of a submediant harmony but as a passing note connecting the  and

and  of the dominant harmony. Fx in measure 360 is not the resolution of the leading tone

of the dominant harmony. Fx in measure 360 is not the resolution of the leading tone  but a link between the

but a link between the  and

and  of the prolonged dominant. A similar situation exists in the second half of measure 361, where the spelling of Liszt's E as Dx more accurately conveys its role as a lower neighbor to the leading tone. Thus the three measures in question can be perceived as the expansion of a single harmony, with passing and neighboring notes filling in arpeggiations of dominant pitches. Entire chords are built from the synchronous activity of various non-harmonic pitches.

of the prolonged dominant. A similar situation exists in the second half of measure 361, where the spelling of Liszt's E as Dx more accurately conveys its role as a lower neighbor to the leading tone. Thus the three measures in question can be perceived as the expansion of a single harmony, with passing and neighboring notes filling in arpeggiations of dominant pitches. Entire chords are built from the synchronous activity of various non-harmonic pitches.

The preceding discussion demonstrates the artistic vitality inherent in the notion of structural levels. Far from being an abstract conception imposed upon music by unyielding analysts, these various strata develop organically out of the music's very fabric. Despite the popular conception that Schenkerians deal with exactly three levels of structure (Foreground, Middleground, and Background), it is more likely that a work will reveal more than three distinct levels.3 A single chord containing the pitches  ,

,  ,

,  , and B represents the basic structural intent of the nearly one hundred pitches (themselves structurally variegated) sounded in measures 360 through 362, while this chord is itself part of a prolongation of

, and B represents the basic structural intent of the nearly one hundred pitches (themselves structurally variegated) sounded in measures 360 through 362, while this chord is itself part of a prolongation of  spanning measures 334 through 363. These thirty measures develop out of a yet more basic level of structure, and so on.

spanning measures 334 through 363. These thirty measures develop out of a yet more basic level of structure, and so on.

A few measures earlier in the Sonata, similar melodic material is rendered within a considerably more complex structural framework. The score shown in Example 3 would elicit an abundance of Roman numerals from some analysts. Yet perhaps a single label is sufficient: the lowered mediant ( ) in

) in  major.

major.

Example 3. Sonata in B Minor

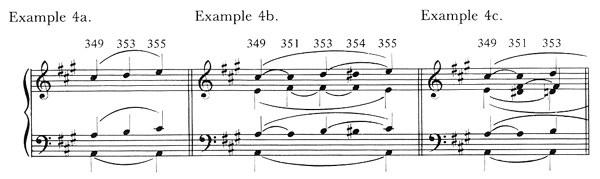

That the passage begins and ends on A major is obvious; why its second segment begins on B minor (measure 353) is less so. Is B minor functioning harmonically, either in the local key of A major or the larger context of  major? Or is its derivation contrapuntal? Example 4a reveals how B minor might result from the linear unfolding of the A-major triad's intervals A-

major? Or is its derivation contrapuntal? Example 4a reveals how B minor might result from the linear unfolding of the A-major triad's intervals A- and

and  -E. The B, instead of serving as the root of a functional harmony, here follows the norm of third-species counterpoint by connecting two consonant pitches over a stationary bass. Even without the bass, which makes the B and D dissonant, the remaining voices of Example 4a would demonstrate motion typical of the first species of counterpoint.

-E. The B, instead of serving as the root of a functional harmony, here follows the norm of third-species counterpoint by connecting two consonant pitches over a stationary bass. Even without the bass, which makes the B and D dissonant, the remaining voices of Example 4a would demonstrate motion typical of the first species of counterpoint.

Example 4.

The notion that a correlation might exist between the simplicity of Example 4a and the complexity of Liszt's writing in Example 3 could not be formulated without some awareness of structural levels. The graphic analysis of Example 4b retains the basic character of Example 4a yet provides details that confirm its relationship with the actual composition. As in Example 2 passing and neighboring notes in concurrent animation create sonorities that might easily (but mistakenly) be regarded as harmonically motivated. The further refinements in Examples 4c and 4d show that the second segment begins with the completion of a chromatic passing motion from E through  to

to  , thereby providing the end of the first segment with a considerable forward momentum despite the lack of structural motion during measures 351 and 352. The upward thrust of the chromatic passing notes during the remainder of the passage is balanced by the

, thereby providing the end of the first segment with a considerable forward momentum despite the lack of structural motion during measures 351 and 352. The upward thrust of the chromatic passing notes during the remainder of the passage is balanced by the  -E descent in measures 354-55. (Compare Examples 4b and 4e.)

-E descent in measures 354-55. (Compare Examples 4b and 4e.)

In music in which harmonic progression plays a central role, phrases and subphrase units typically possess harmonic goals such as tonic or dominant. But what might serve as a goal for internal phrase units in passages in which harmony is not a factor of chordal succession? Example 4c has hinted at an interesting answer. Example 5, from "Vallée d'Obermann" (Années de Pèlerinage: Suisse), provides a further confirmation.

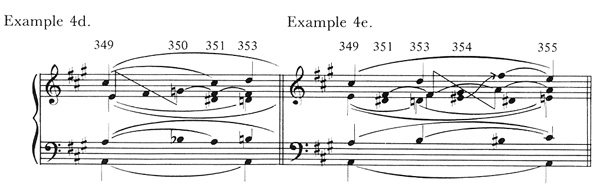

Example 5. Vallée d'Obermann

The segment from measure 25, beat 4, through measure 33 begins and ends on what is perceived in context as a dominant harmony in the key of E minor (despite Liszt's spelling of its opening chord). Proponents of a harmonic explanation for the passage must consider how  minor (measure 28) functions in an E-minor context and what motivation exists for the mapping of measures 25-28 into measures 28-31 at the interval of a diminished fifth.

minor (measure 28) functions in an E-minor context and what motivation exists for the mapping of measures 25-28 into measures 28-31 at the interval of a diminished fifth.

Of course a scheme of Roman-numeral labels could be formulated for the passage. It might incorporate several pivot chords so that both  and A could be represented as tonics. Such an interpretation would probably motivate statements concerning Liszt's daring handling of distantly related keys. Yet it would not account for the continuity that these measures clearly possess.

and A could be represented as tonics. Such an interpretation would probably motivate statements concerning Liszt's daring handling of distantly related keys. Yet it would not account for the continuity that these measures clearly possess.

A consideration of structural levels and an emphasis upon the linear dimension of the passage reorient our appreciation of Liszt's creativity. Harmonic progression, which is useless in explaining the motivation for the  and A arrival points and their relationship, is not the critical issue here. Instead, Liszt's handling of passing and neighboring notes is worthy of our careful attention, as well as our admiration.

and A arrival points and their relationship, is not the critical issue here. Instead, Liszt's handling of passing and neighboring notes is worthy of our careful attention, as well as our admiration.

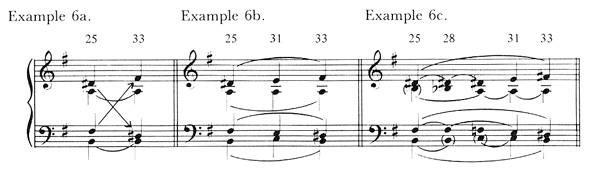

In addition to the octave displacements and the inconsistent spelling, the  and

and  in the dominant chords of measures 25 and 33 exchange positions. Example 6a shows this transformation. The horizontal succession of

in the dominant chords of measures 25 and 33 exchange positions. Example 6a shows this transformation. The horizontal succession of  and

and  invites the incorporation of E as a passing note. In fact, passing motion in both directions is possible, as in Example 6b. The middle chord of this succession is not to be construed as the harmonic successor of the first dominant chord: E does not resolve the leading tone; A is not the chord's "root"; C is embellishing the dominant's root B, not replacing it.

invites the incorporation of E as a passing note. In fact, passing motion in both directions is possible, as in Example 6b. The middle chord of this succession is not to be construed as the harmonic successor of the first dominant chord: E does not resolve the leading tone; A is not the chord's "root"; C is embellishing the dominant's root B, not replacing it.

Example 6.

The next step in our gradual recomposition of the passage involves chromatic passing notes. Example 6c shows that the dominant's seventh (A) is intensified through motion from B. (In the score this motion begins as  -

- in the bass.) In that the descent from B to A is chromatic, the pitches

in the bass.) In that the descent from B to A is chromatic, the pitches  ,

,  , and

, and  are juxtaposed. Thus what appears in the score as an

are juxtaposed. Thus what appears in the score as an  -minor chord—the goal of measures 25 through 28—is in fact the by-product of a chromatic linear descent frozen for a few moments in a state of incompletion! By recognizing, in terms of Example 6c, that measures 26 and 27 unfold the chord that comes to rest in measure 28 and that measures 29 and 30 similarly project the chord of measure 31, the entire passage comes into focus. Liszt's free handling of voices and registers (such as placing the tenor

-minor chord—the goal of measures 25 through 28—is in fact the by-product of a chromatic linear descent frozen for a few moments in a state of incompletion! By recognizing, in terms of Example 6c, that measures 26 and 27 unfold the chord that comes to rest in measure 28 and that measures 29 and 30 similarly project the chord of measure 31, the entire passage comes into focus. Liszt's free handling of voices and registers (such as placing the tenor  [

[ ]-

]- -E at the bottom of the texture and projecting the alto

-E at the bottom of the texture and projecting the alto  -A to the top of the texture) allows for the dramatic linear descent in the left-hand part and for the corresponding yet somewhat less linear ascent in the right.

-A to the top of the texture) allows for the dramatic linear descent in the left-hand part and for the corresponding yet somewhat less linear ascent in the right.

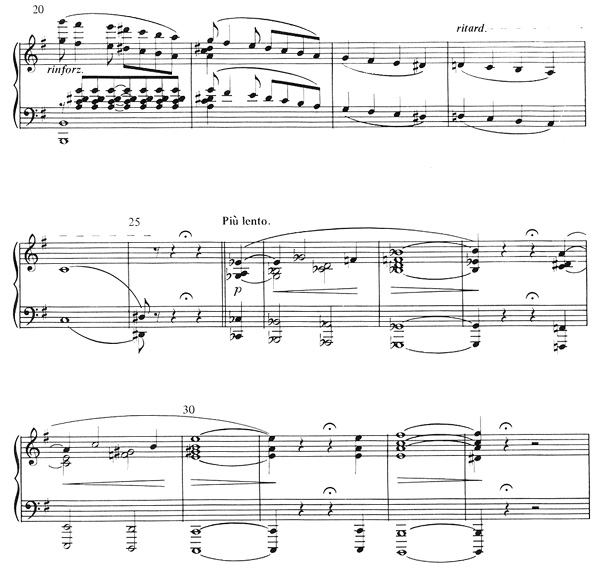

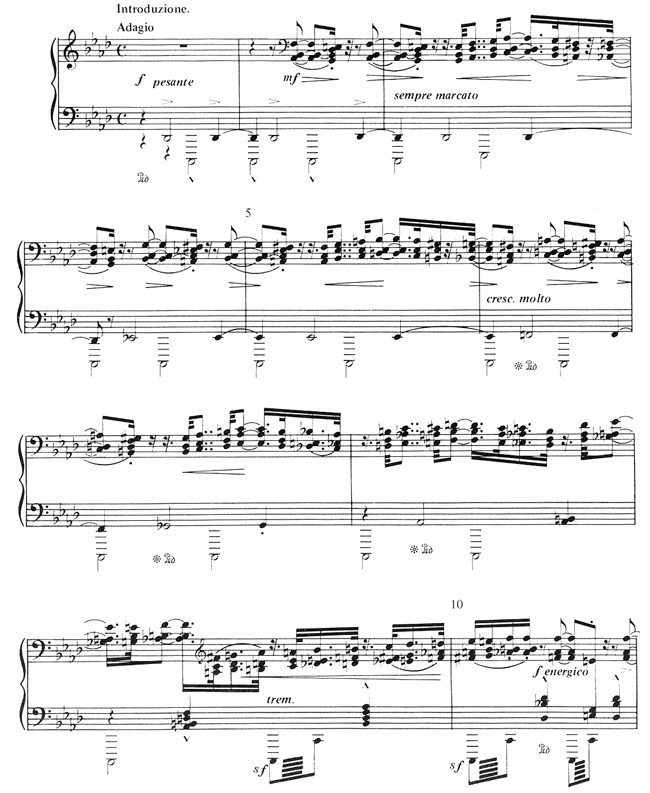

"Funérailles," from Liszt's Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, opens with a remarkable and celebrated succession of diminished-seventh sonorities, none of which seems to behave as traditional harmony texts would prescribe. Example 7, a portion of the Introduzione, defies rational explanation as a harmonic progression. Fortunately a consideration of structural levels unlocks many of its mysteries.

Example 7. Funérailles

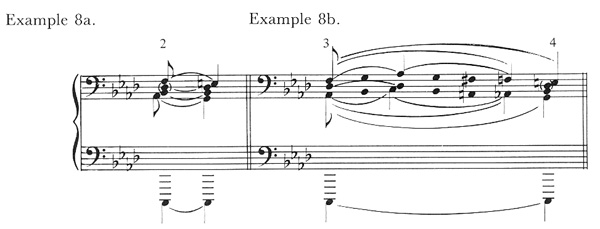

A most straightforward sort of dependence is displayed in Example 8a. Here the sigh figure traditionally associated with death (e.g., in the "Crucifixus" from Bach's Mass in B Minor; in "Dido's Lament" from Purcell's opera) appears in two voices, embellishing a dominant-ninth sonority built on the root C. (Tonic F appears first in measure 24.) Even when these neighboring notes are themselves embellished (Example 8b), their structural dependency upon  and G remains obvious.

and G remains obvious.

Example 8.

Similar procedures are operative through measure 8. The resulting basic structural pattern, represented by Example 9, shows no sign of harmonic motivation. Instead linear forces bridge the space between the pitches of measures 2 and 8, all over the unwavering bass pitch C.

Example 9.

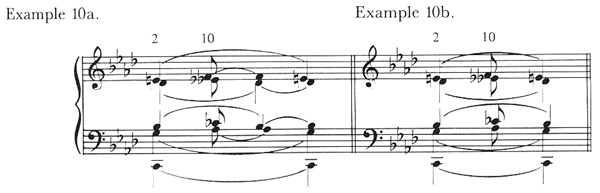

Arpeggiation is the principal prolongational tool in measures 8 through 10, in which the diminished-seventh sonority of measure 8 rises upwards. Connecting these chords is passing motion much like that outlined in Example 9, here proceeding at a much accelerated rate and in unmitigated chromatic succession. By recognizing that this arpeggiation prolongs a single sonority, we can now formulate an incisive clarification of the excerpt as shown in Examples 10a and 10b.

Example 10.

Registers are normalized; spellings are revised to elucidate structural meaning. The foundation for the passage is, basically, an expansion of the motive first presented in measure 2 (Example 8a).

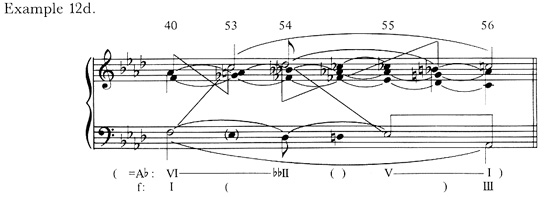

In each of the preceding excerpts a single harmony was prolonged. Even when a progression of harmonies does play a structural role, as in our final excerpt (also from "Funérailles"), the techniques demonstrated will prove indispensable. One of the principal features of Example 11 is the shift of tonal center from the tonic (F minor) to the mediant ( major).

major).

Example 11. Funérailles

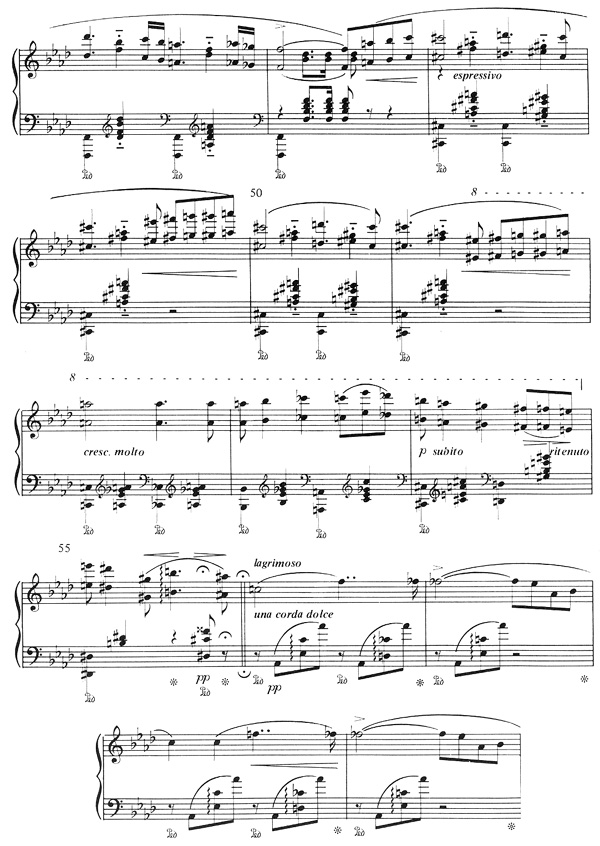

Example 12a provides a rudimentary orientation. Though the validity of the C- -C motive in the soprano has yet to be demonstrated, its kinship with

-C motive in the soprano has yet to be demonstrated, its kinship with  -F-

-F- in Example 10b and with the juxtaposition of

in Example 10b and with the juxtaposition of  and C in measure 1 (see Example 7) should be obvious.

and C in measure 1 (see Example 7) should be obvious.

A critical factor in confirming Example 12a is to illustrate how the  -C-

-C- -

- chord of measure 53 functions as an extension of the F-minor tonic of measure 40 (Example 12b).

chord of measure 53 functions as an extension of the F-minor tonic of measure 40 (Example 12b).

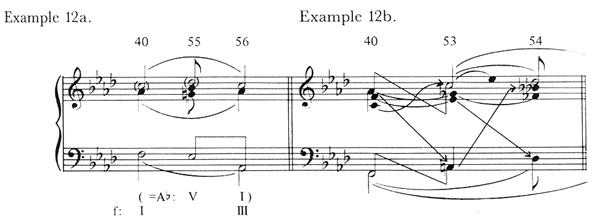

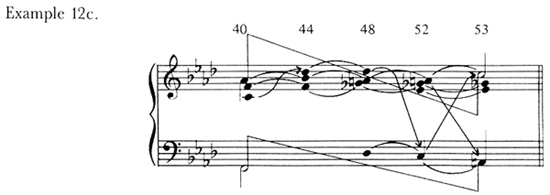

Example 12.

Example 12c posits that in measure 44  and

and  emerge as upper neighbors to the third and fifth of the tonic triad. (Remember that the third and fifth of the dominant triad were embellished by upper neighbors also—see Example 8a.) Both pitches fulfill their mission as neighbors, for

emerge as upper neighbors to the third and fifth of the tonic triad. (Remember that the third and fifth of the dominant triad were embellished by upper neighbors also—see Example 8a.) Both pitches fulfill their mission as neighbors, for  (substituting for

(substituting for  ) and C fall into place in measures 48 and 52, respectively. Yet in the meantime

) and C fall into place in measures 48 and 52, respectively. Yet in the meantime  and

and  , both emanating from the root F, arrive. By normalizing registers for clarity, we see in Example 12d that

, both emanating from the root F, arrive. By normalizing registers for clarity, we see in Example 12d that  is a neighboring note between F and

is a neighboring note between F and  and that the

and that the  passes between F and

passes between F and  . Measure 53 in Example 12d is to the root F of measure 40 what the

. Measure 53 in Example 12d is to the root F of measure 40 what the  -G-

-G- -

- of measure 2 is to the root C below it (see Example 7).

of measure 2 is to the root C below it (see Example 7).

Some analysts would apply additional Roman numerals to Example 12d. Yet could any harmonic label adequately explain the complex situation of measure 53 in terms of its progression into measure 54? Like many of Liszt's diminished-seventh chords, this one is linearly motivated. Later in measure 54, applying some sort of symbol below  might seem innocuous, yet it would foster the notion that

might seem innocuous, yet it would foster the notion that  "resolves" on

"resolves" on  . Not true!

. Not true!  connects

connects  and

and  ; the Neapolitan leads to the dominant (in

; the Neapolitan leads to the dominant (in  major) even if another chord intervenes. Finally, some analysts would regard the first chord of measure 55 as a second-inversion tonic in

major) even if another chord intervenes. Finally, some analysts would regard the first chord of measure 55 as a second-inversion tonic in  . The incompatibility of that view and the methodology of this paper should be apparent.

. The incompatibility of that view and the methodology of this paper should be apparent.

These demonstrations provoke several resolutions concerning future study of Liszt's chromaticism and, by extension, chromaticism in general. First, we should analyze what we hear rather than what we see. In many cases Liszt's pitch notation does not reflect structural function. Second, we should emancipate various sonorities, particularly the diminished seventh, from the implications that textbooks traditionally have attributed to them. The ways in which a specific combination of pitches might come into being are too numerous to catalogue. To insist upon a harmonic interpretation for every such combination is to neglect the linear possibilities that Liszt and others clearly regarded as vital components of their art. Third, we should acknowledge that contrapuntal features such as passing and neighboring notes occur at various structural levels, not only in the immediate foreground. Fourth, we should reject the notion that an adequate analysis could consist of a few jottings and numerals between the staves of the score itself. Finally, we should take precautions in our teaching of basic theory to prevent students from regarding Roman-numeral saturation in analysis as necessary or desirable.

As our analyses attain greater refinement and power, they become correspondingly more complex and difficult to create and understand. We inch our way closer to the inner truth that Liszt's and others' works possess, but we are in danger of leaving the nonspecialist behind. Despite its flaws, the old Roman-numeral approach to analysis was understood almost universally by educated musicians. Now, having told them that their vocabulary of labels is outmoded, we have yet to find effective means for making our ideas widely available. Yet a retreat is not in order. We will create a positive environment for the pursuit of analysis not by offering simple yet defective methods but by creating alternatives that are self-motivating because of the insights they provide. It is in that context that this essay is offered: not as an appeal for greater specialization, but in confirmation of our discipline's ability to respond meaningfully and as straightforwardly as possible to a significant yet complicated segment of our repertory.

1Arnold Schoenberg's Structural Functions of Harmony (New York: Norton, 1954) typifies this tendency.

2A groundbreaking work in this area is Felix Salzer's Structural Hearing: Tonal Coherence in Music, 2 vols. (New York: Boni, 1952), which is considerably more varied in repertory than is Schenker's Der freie Satz, 2 vols. (Vienna: Universal, 1935); in English as Free Composition, trans. Ernst Oster, 2 vols. (New York: Longman, 1979). Salzer's revisionist view persists in the writing of many analysts, including my "Structural Foundations of 'The Music of the Future': A Schenkerian Study of Liszt's Weimar Repertoire" (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1981). David Beach has compiled listings of all such works in his "A Schenker Bibliography," Journal of Music Theory 13 (1969):2-37; "A Schenker Bibliography: 1969-1979," Journal of Music Theory 23 (1979):275-86; and "The Current State of Schenkerian Research," Acta Musicologica 57 (1985):275-307.

3Schenker states, "It is impossible to generalize regarding the number of structural levels, although in each individual instance the number can be specified exactly (Free Composition, 263)."