Tradition and Creation: Hugo Wolf's "Fussreise"

Written by Christopher Hatch

Symposium Volume 28

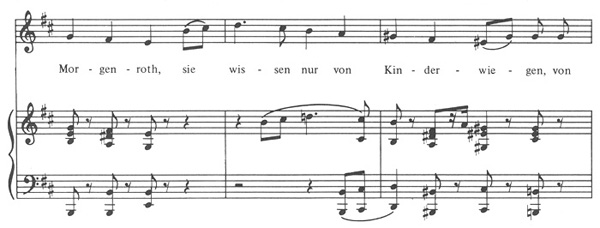

In a letter of 21 March 1888, Hugo Wolf spoke boastfully about his latest composition: "I retract the opinion that 'Erstes Liebeslied eines Mädchens' is my best thing, for what I wrote this morning, 'Fussreise' (Eduard Mörike), is a million times better."1 Over the years both critics and audiences have also placed a high valuation on Wolf's "Fussreise" (Mörikelieder, no. 10). Yet however masterful and original this song is thought to be, any such nineteenth-century work reuses already existing materials, rethinks ideas already expressed. Locating and designating these materials or ideas in this lied can suggest how it was conceived and how it may be analyzed.

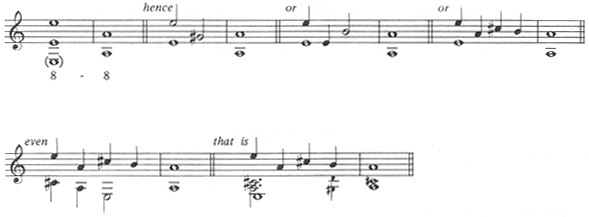

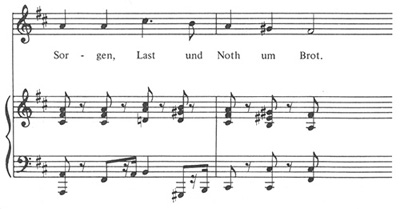

The materials and ideas referred to here are not abstractions, but concrete and complex entities—musical fragments, if you will. The cadence by which "Fussreise" marks an attainment of the dominant (Example 1a) is just such a bit of music; it states the full close in the way many other pieces do (Examples 1b-f).

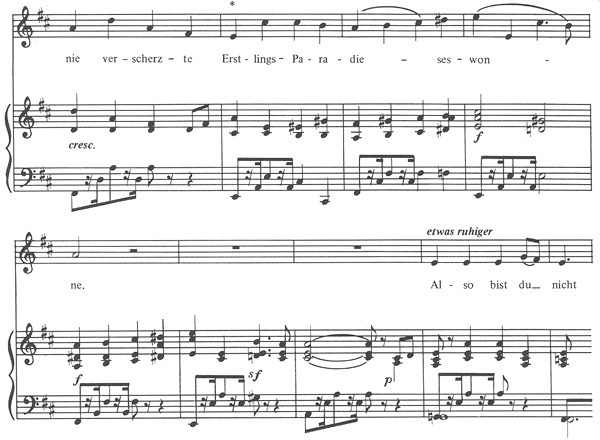

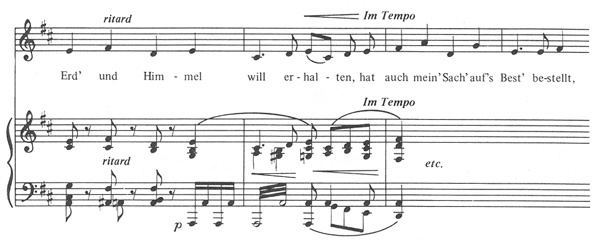

Example 1a. Wolf, Fussreise, mm. 36-44.

Example 1b. Schumann, Opus 77 No. 1, Der frohe Wandersmann, mm. 7-14.

Example 1c. Schumann, Opus 68 No. 17, Kleiner Morgenwanderer, mm. 17-20.

Example 1d. George Henschel, Opus 17 No. 2, Wanderlied, mm. 8-10.

Example 1e. Mendelssohn, Opus 86 No. 2, Morgenlied, mm. 7-10.

Example 1f. Mendelssohn, Opus 57 No. 6, Wanderlied, mm. 27-31.

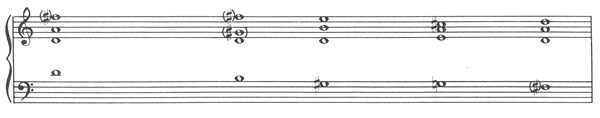

Each of the decisive cadences given in Examples 1a-f represents a solution to the same voice-leading problem, namely, the breaking of the outer-voice parallel octaves that fall (or, in the case of Example 1e, would fall) between the onset of the cadential six-four chord and the arrival of the local tonic (Example 2).

Example 2.

In general the characteristics shared between "Fussreise" and the other excerpts of Example 1 in matters of, say, rhythm, spacing, and text-setting are so obvious as to need no comment. The resemblance between Example 1a and 1b is so especially close and hints that perhaps further correspondences between "Fussreise" and Schumann's Opus 77, no. 1, "Der frohe Wandersmann," should be expected. This conjecture will be tested below.

With regard to Example 1a and Example 1c the behavior of another six-four chord (marked with an asterisk) draws attention to itself. This earlier six-four moves on to the submediant chord, and together the two chords function as a precadential progression whose simplest expression is included in Example 3.

Example 3.

Like "Der frohe Wandersmann," Schumann's "Kleiner Morgenwanderer," no. 17 in his Album für die Jugend, Opus 68, shows here enough local congruence with "Fussreise" to arouse one's curiosity: do other conformities exist between the Wolf song and the Schumann character piece? This question too will be pursued.

Between "Fussreise" and "Der frohe Wandersmann" one large-scale resemblance manifests iteslf. A clue to its location occurs right after the dominant cadences excerpted in Examples la and b, where the same diminished chord,  -A-C-(E), replaces the preceding A-major harmony. In each song this progression begins a section that will close in the key of

-A-C-(E), replaces the preceding A-major harmony. In each song this progression begins a section that will close in the key of  . In "Der frohe Wandersmann" a four-bar period in E minor (mm. 13-16) is without alteration transposed up a whole step to cadence in

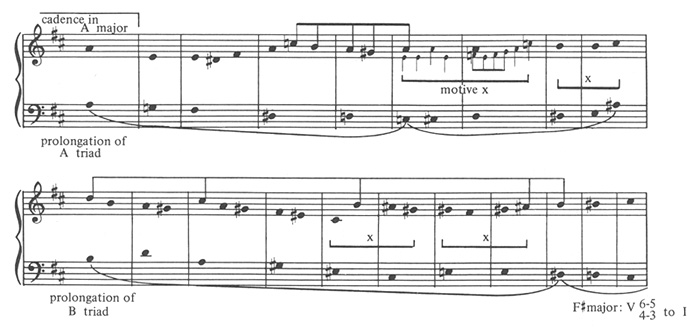

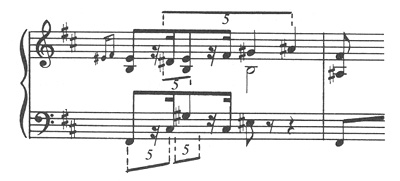

. In "Der frohe Wandersmann" a four-bar period in E minor (mm. 13-16) is without alteration transposed up a whole step to cadence in  minor (m. 20). "Fussreise" works out the same idea (that is, a twofold cycle created by upward transposition by a whole step), but without exact repetition or regular periodicity. Example 4 sketches the procedure, which involves the prolongation of a chord on A, moving from a major triad in five-three position to a minor in six-three (mm. 42-47), and, matching this, the prolongation of a chord on B, moving from a minor triad in five-three position to a major in six-three (mm. 51-59).

minor (m. 20). "Fussreise" works out the same idea (that is, a twofold cycle created by upward transposition by a whole step), but without exact repetition or regular periodicity. Example 4 sketches the procedure, which involves the prolongation of a chord on A, moving from a major triad in five-three position to a minor in six-three (mm. 42-47), and, matching this, the prolongation of a chord on B, moving from a minor triad in five-three position to a major in six-three (mm. 51-59).

Example 4. Fussreise, see mm. 42-61.

The ends of the prolongations are signaled by the disappearance of the dissonance-to-resolution moves contained within most of the preceding measures. Other ways in which the two matching segments of mm. 42-50 and mm. 51-60 resemble each other are the use of the repeated motive, x, in mm. 47-50 and 55-58, and the submerged recurrence of the upper-voice motion that is indicated by the beamed long stems. In their second appearance the returning harmonic, motivic, and other melodic elements have a different temporal alignment with each other. Again, as with the Schumann song, the middle section cadences in the key of  —in "Fussreise"

—in "Fussreise"  major (m. 63).

major (m. 63).

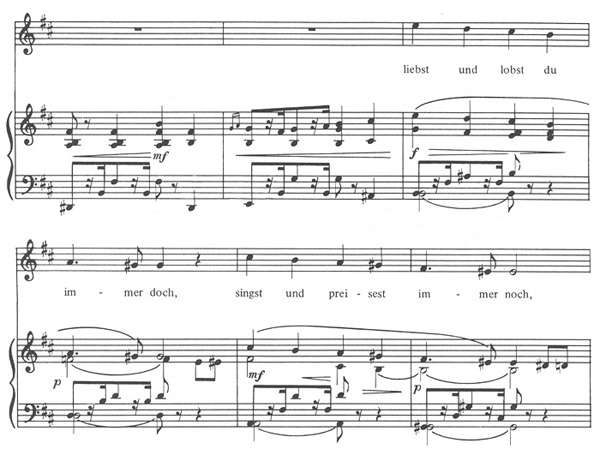

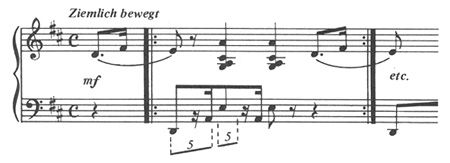

Thus the most modulatory internal sections of the Wolf and Schumann songs possess strong structural parallels: they share a skeletal harmony. But the harmonic format is in no sense an extraordinary one, and the relationship between these particular sections might remain largely formal rather than becoming readily perceptible were it not for moments like those shown in Examples 5a and b. In these excerpts the similarities are confirmed not through one or another parameter taken singly but by general shapes that ally the passages. Despite harmonic divergences, some measures in the central section of "Kleiner Morgenwanderer" also seem cut from the same cloth (see Example 5c).

Example 5a. Fussreise, mm. 49-54.

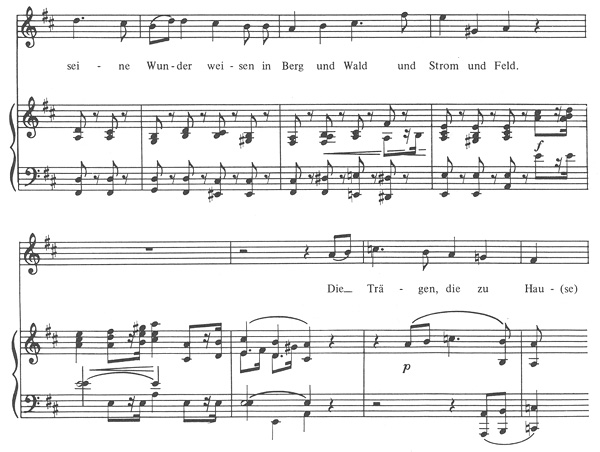

Example 5b. Die frohe Wandersmann, mm. 16-20.

Example 5c. Kleiner Morgenwanderer, mm. 10-14.

With regard to harmony, the procedures by which "Fussreise" prolongs the chords on A and B parallel the techniques found in the opening section of "Der frohe Wandersmann." In this passage the tonic triad is again extended from an initial appearance in five-three position to a concluding six-three chord (m. 7). The progression printed as Example 6a underlines the prolongations realized in both songs. Examples 6b-d represent in greater detail the outer voices and the successive harmonies of the passage found in "Der frohe Wandersmann" and the two in "Fussreise," which are now set out in the key of D to facilitate comparison. For all the linear elaboration and the more expansive rhythmic progress of the measures written by Wolf, the deployment of the harmonies is similar enough to allow each passage to recall the others.

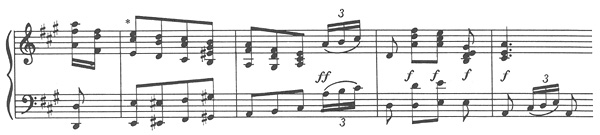

Example 6a.

Example 6b. Der frohe Wandersmann, see mm. 4-7.

Example 6c. Fussreise, see mm. 42-47.

Example 6d. Fussreise, see mm. 51-59.

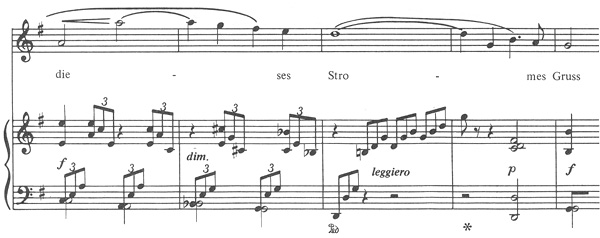

Likewise in the use of pedal points situations of discernible similarity arise. The character piece by Schumann as well as his song introduces a dominant pedal after that key has arrived (in the song after the second time the dominant is reached; see Example 5c and 7a). In "Fussreise" pedal points are continually appearing. A comparison of dominant pedal points reveals some notable differences between Wolf and Schumann along with the similarities. In the second of the two dominant pedal points in "Fussreise" a recurrent dissonating tritone above the bass (i.e.,  above A; see Example 7b) is bereft of the full harmonic explanation that Schumann has provided for the corresponding

above A; see Example 7b) is bereft of the full harmonic explanation that Schumann has provided for the corresponding  in "Kleiner Morgenwanderer" and

in "Kleiner Morgenwanderer" and  in "Der frohe Wandersmann." (An American song offers a curious parallel to "Fussreise" here. In Charles Ives's "Walking" much the same scale as Wolf uses in mm. 26ff. is expressed at a pedal point one whole step lower; the intervals Wolf calls for above the pedal note A Ives has written above G. See Example 7c.)

in "Der frohe Wandersmann." (An American song offers a curious parallel to "Fussreise" here. In Charles Ives's "Walking" much the same scale as Wolf uses in mm. 26ff. is expressed at a pedal point one whole step lower; the intervals Wolf calls for above the pedal note A Ives has written above G. See Example 7c.)

Example 7a. Der frohe Wandersmann, mm. 33-35, piano part only.

Example 7b. Fussreise, mm. 26-30.

Example 7c. Charles Ives, Walking, mm. 29-30.

In "Fussreise" the pair of upward fifths, D-A-E, stated over the opening tonic pedal (Example 8a) seems to color the sound of the entire song. From beginning to end the spacing of conventional harmonies, though created by traditionally correct part-writing and properly used "nonharmonic" notes, operates to bring out their "fifthness". Example 8b presents a good instance of this. In the two Schumann pieces such materials appear almost exclusively as closing gestures (Examples 8c and d). Thus in small dimensions Schumann uses an idea that permeates the Wolf song as a whole. (At this point a second reference to Ives's "Walking" becomes relevant, for in this song fifths are brought out not only through much parallel-fifth writing between chords but also through vertical fifths within chords, especially the one given in Example 8e.)

Example 8a. Fussreise, mm. 1-3.

Example 8b. Fussreise, mm. 67-68.

Example 8c. Der frohe Wandersmann, mm. 46-50.

Example 8d. Kleiner Morgenwanderer, mm. 24-29.

Example 8e. Walking, m. 4.

The opening measures of "Fussreise" establish a distinctive role for the note E. This note, which enters as a supertonic displacement of the mediant,  , acquires a marked tendency to rise, and repeatedly this tendency is fulfilled. Schumann's "Der frohe Wandersmann" emphasizes the same 2-3 move, which is highlighted most of all in the passage where the voice returns to its opening strain for the last time (Example 9). The postlude of the song closes with a 2-3 gesture (see Example 8c).

, acquires a marked tendency to rise, and repeatedly this tendency is fulfilled. Schumann's "Der frohe Wandersmann" emphasizes the same 2-3 move, which is highlighted most of all in the passage where the voice returns to its opening strain for the last time (Example 9). The postlude of the song closes with a 2-3 gesture (see Example 8c).

Example 9. Der frohe Wandersmann, mm. 37-40.

In both songs the pull upwards to the mediant, continually and strongly expressed in the course of the melody, operates in the harmonic sphere as well. For instance, both songs introduce an applied dominant before the  triad during the move to the dominant key (see Examples 1a and b), and both direct an important modulation to the key of

triad during the move to the dominant key (see Examples 1a and b), and both direct an important modulation to the key of  , which acts as a terminal point in the middle sections that were described above.

, which acts as a terminal point in the middle sections that were described above.

When scale steps 2 and 3 of the dominant appear, they are at the same time reinterpretations of the original key's 6 and 7; each song inevitably presents B moving to  in this context. With a fresher meaning this pair of notes also takes on prominence in the original key. The piano prelude and interludes of the Schumann lied feature the upward thrust of scale steps 6-7-8 (Example 10a), and in "Fussreise" the same ascent is made repeatedly, most notably at the conclusion of the vocal line (Example 10b). The Schumann piano piece closes in somewhat the same way (see Example 8d above and Example 10c).

in this context. With a fresher meaning this pair of notes also takes on prominence in the original key. The piano prelude and interludes of the Schumann lied feature the upward thrust of scale steps 6-7-8 (Example 10a), and in "Fussreise" the same ascent is made repeatedly, most notably at the conclusion of the vocal line (Example 10b). The Schumann piano piece closes in somewhat the same way (see Example 8d above and Example 10c).

Example 10a. Der frohe Wandersmann, m. 1.

Example 10b. Fussreise, mm. 77-78.

Example 10c. Fussreise, mm. 26-28, right hand, some notes transposed an 8ve up.

As a last point of similarity one might focus on the conspicuous stepwise contrary motion accompanying the end of the vocal line in "Fussreise," Example 10b. Such part-writing appears earlier in the song only once, in m. 73. "Kleiner Morgenwanderer," on the other hand, uses this kind of contrary motion over and over again (see Examples 1c and 5d above). What stands out by its rarity in the song is in the piano piece standard procedure.

The commentary on the series of examples set forth here deals largely with matters of pitch rather than those of phrasing, rhythm, meter, or tempo. But essential similarities occur in these areas, with like rhythmic events framing and controlling like harmonic and melodic events. Luckily the handful of musical illustrations already presented can adequately display the rhythmic conformities whose description might need hundreds of words.

What is the significance of all these relationships, whether of pitch or rhythm? As far as the composing of music is concerned, perhaps it can be said that such a collection of likenesses points at least provisionally to the conclusion that on one level the composer is manipulating just such components as these fragments. This assertion can be contrasted with two other views. The first might be called the constructional view, wherein the composer is seen as the builder of artworks that arise from his labor on the smallest dimensions of a piece, from his shifting about even of single notes. Many musicological studies, especially investigations of composers' sketches and revisions, imply this picture of the composer at work. The other view sees the composer as one who conceives the work as a whole, having come upon a musical idea from which every detail of the work will flow as a necessary consequence. Here is a radiational view, which has the composer controlling the work purely through his understanding of the idea lying at its core. Among others, some philosophers of music believe composing to be creation of this sort.2 Certainly many people would agree that each of these views—the more atomistic, constructional view and the more organic, radiational view—expresses a truth. But what if one suspects that there are constituents in any piece, even a masterwork, that are arrived at neither de novo, from a fine calculation of what results from the placing of each detail, nor again through a grasp of how every note relates to an omnipotent fundamental idea? Acknowledging the force of routine and of remembered formulas would address such suspicions. That the composer achieves completed pieces by working within a tradition, and with the shapes that a tradition has made acceptable and meaningful to him, is another truth about composing.

Neither music lover nor practicing musician nor scholar fails to honor this view in his routine observations on music. Be it in trivial discoveries of "plagiarism" or in highly sophisticated demonstrations of how one piece has been modeled on another, everybody remarks now and then on the fact that the contents of compositions overlap.3 Theorists and pedagogues in particular have reason to stress the common properties in musical products. Serious critics of music too serve their own purposes by locating parallels between compositions. Yet for all this, when investigation focuses on the genesis of individual works, the activating power of tradition is unlikely to be a primary object of study.

For "Fussreise," accepting the role of tradition would mean recognizing that the ideas already embodied in other "open air" or "open road" music had for Wolf a retained value and that he willingly used preexisting materials for the same functions they had earlier fulfilled. By incorporating these materials "Fussreise" takes its place beside such pieces as those cited in Example 1 above, whose titles alone tell a good deal: "Der frohe Wandersmann," "Kleiner Morgenwanderer," "Wanderlied," "Morgenlied," and again "Wanderlied". Wolf's hiking song becomes part of this family. Of course the general category of "wanderer songs" comprises music from several centuries and in many divergent styles. But "Fussreise" and the rest fall within a more localized class, whose members share a fairly specific expressive intent, a wish to project a well-defined attitude toward life. The journeyers who walk through these particular pieces are not displaced persons, alienated wanderers out of step with the world. Rather, with high spirits and at peace with God, they set out in the morning to make their way on foot, choosing, as Ives's text puts it, not "to die or to dance, but to live and walk." Belonging to this expressive realm in the minds of Schumann, Wolf, and other composers was a stock of well-formed musical ideas and materials, which for Wolf would crystallize in "Fussreise".4

Eric Sams in his book on The Songs of Hugo Wolf has done invaluable work in explicating the expressive intentions of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic motives prominent in Wolf's lieder. He discusses passages in "Fussreise" as cognates with those in some other Wolf songs; specifically, music given in Examples 1a and 10b above is linked by Sams to Wolf's "Morgentau Gebet" (Mörikelieder, no. 28), and "Selbstgeständnis" (Mörikelieder, no. 52).5 From his knowledge of Wolf's style Sams is able, moreover, to characterize the key of  major, in which "Fussreise" climaxes, as one that "Wolf often reaches at moments of great elation."6 Another feature that Sams finds in "Fussreise," namely, the "horn passages" that he associates with Wolf's expression of "freedom," may be related to the accompaniment's use of vertical fifths (see Examples 8a and b above). Of course the nature of Sams's topic and method limits his searching broadly, in other composers' works, for affinities with Wolf's ideas and materials.

major, in which "Fussreise" climaxes, as one that "Wolf often reaches at moments of great elation."6 Another feature that Sams finds in "Fussreise," namely, the "horn passages" that he associates with Wolf's expression of "freedom," may be related to the accompaniment's use of vertical fifths (see Examples 8a and b above). Of course the nature of Sams's topic and method limits his searching broadly, in other composers' works, for affinities with Wolf's ideas and materials.

As far as analyzing music is concerned, the collection of such likenesses points to some neglected tasks at hand. Nowadays advanced analytic endeavors in every kind of art tend to focus closely on the individual work and to trust to the efficacy of self-enclosed analytic systems. In the face of this it may be perverse to suggest that musical analysis would gain by dwelling on the fact that the subject of one work is in a sense the other works written in the same vein. But if analysis is to deal with what a given composition contains, then some of its branches must try vigorously to come to terms with the tradition-established usages within it.7

Work on the import of these usages does not need to await irrefutable answers to the time-honored questions in aesthetics, what can music express and how can it express it. Analysis, having its own aims, may leave aside these elemental philosophical concerns, which such skilled thinkers as Peter Kivy and Edward T. Cone have recently addressed.8 Not required either and perhaps not wanted is any set of prior findings as to the meaning of this or that musical fragment. What tradition creates is so dependent on context, so enmeshed in actual musical events, that a dictionary like the one that Deryck Cooke hoped to provide in The Language of Music would be of little if any help.9 Instead music analysts might initiate their efforts by investigating repertories that cohere in terms of chronology, geography, and genre and adducing therefrom the evidence that bears directly on the piece to be analyzed.

Common sense endorses a catholic and pragmatic approach like this. By contrast hermetic methods, however fruitful, can seem at first blush unnatural, at least when applied to the visual arts and literature. Connoisseurs in the field of fine arts, for instance, would be puzzled by an analysis of a nineteenth-century painting that ignored any and all pictorial, narrative, and iconographic meanings that stemmed from other paintings of the same sort. Yet accepting the corresponding limitations in an analytical study of, say, a nineteenth-century song like "Fussreise" appears less questionable. To put such limitations into question is one reason for collecting the likenesses given above.

1Quoted in Frank Walker, Hugo Wolf: A Biography, 2d. ed. (London: Dent, 1968), 205.

2See, for example, Patricia Carpenter, "Musical Idea and Musical Form: Variations on a Theme of Schoenberg, Hanslick, and Kant," in Music and Civilization: Essays in Honor of Paul Henry Lang, ed. Edmond Strainchamps, Maria Rika Maniates, and Christopher Hatch (New York: Norton, 1984), 394-427.

3The many studies of modeling usually show the composer's mind fixed on a single prototype, which is not at all the topic of the present article.

4Walter Wiora finds that "Fussreise" belongs to a longstanding tradition with respect to both its rhythm and the contour of its opening melody; see his Das deutsche Lied: Zur Geschichte und Ästhetik einer musikalischen Gattung (Wolfenbüttel and Zurich: Möseler Verlag, 1971), 20.

5Eric Sams, The Songs of Hugo Wolf, 2d ed. (London: Eulenburg Books, 1983), 45, 80, 107, and 145.

6Ibid., 80 (see also 34-35). The  -major modulation in "Fussreise" may be compared to the move to the same key in m. 38 of George Henschel's Opus 17, no. 2, "Wanderlied" (quoted in Example 1d above), which is also in D major.

-major modulation in "Fussreise" may be compared to the move to the same key in m. 38 of George Henschel's Opus 17, no. 2, "Wanderlied" (quoted in Example 1d above), which is also in D major.

7This task is related to what Leonard B. Meyer terms the little explored field of "musical iconography"; see his Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 69-70.

8Peter Kivy, The Corded Shell: Reflections on Musical Expression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980), and Edward T. Cone, The Composer's Voice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), esp. 158-75.

9Deryck Cooke, The Language of Music (London: Oxford University Press, 1959).