It is only since Japan's recovery from the second world war that Japanese composers have fully assimilated the Western musical vocabulary, obscuring the traditional distinctions between Western and Japanese music. Of the generation of composers reaching maturity in the postwar years, the strongest international impact has been made by Toru Takemitsu (b. 1930). In this respect, he is the foremost representative of a new era in Japanese composition.

Acutely aware of the contradictions inherent in identifying himself both as Japanese and as a composer in the Western sense, Takemitsu writes:

I cannot ignore the century of Japan's contact with the West, though I have doubts about how to interpret it. If I ignored it, I would risk denying the present. I think that Japan and my own life have been in the midst of great contradictions. . . . Instinctively, I would not try to solve the contradictions in any simple way—either those between Japan and the West, or those within me. I would prefer, in fact, to deepen many of the contradictions, and make them more vivid.1

Takemitsu's music transcends earlier efforts to blend Eastern and Western idioms through a subtle aesthetic balance of opposing features. While his music embodies a strong innate logic, it is rich in mystery and ambiguity. He creates a musical expression which can be austere and impersonal yet deep in its projection of human spirit. Because Takemitsu is uncompromising in maintaining his strong personal identity both as a Japanese and a modern (i.e., Western) composer, his music is never a simple compromise of Eastern and Western idioms.

Traditional Japanese aesthetic values are reflected in Takemitsu's sensitivity to timbral and textural relationships, his use of traditional Japanese instruments and his spatial positioning of instruments.2 But as this study will show, Takemitsu's music can also be viewed as a modern reflection of traditional Japanese concepts of time. In the solo piano works, Takemitsu constructs a characteristically Oriental image of time using twentieth-century Western musical materials.

While relatively few of Takemitsu's concert works incorporate traditional Japanese instruments, traditional Japanese aesthetic values and ways of thinking continue to be manifested in his works conceived for Western instrumental idioms. This is accomplished in the solo piano works through an emphasis on the spatial qualities of music, the expressive meaning ascribed to spans of silence, and a sensitivity to the absolute beauty of isolated moments and individual sound events.3

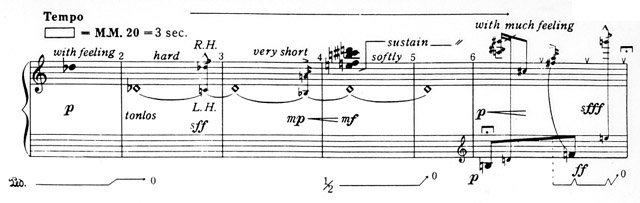

Takemitsu has said, "To make the void of silence live is to make live the infinity of sounds. Sound and silence are equal."4 In his first published work for solo piano, Pause ininterrompue (1952-60), Takemitsu creates silences rich in expressive meaning through musical gestures which begin quietly and gradually fade to inaudibility. This is evident in the opening of the second movement, entitled "Quietly and with a cruel reverberation," shown in Example 1.

Example 1. Takemitsu's Pause ininterrompue, No. 2, mm. 1-11

In performance, the chord at m. 9 may not remain audible to the listener for the full 7 1/2 seconds notated. This does not, however, indicate any flaw in the performance or the score. The composer has carefully gauged the sustaining powers of the instrument, choosing dynamic and durational levels which focus attention of the performer and listener on the isolated sonority as it fades to silence over the desired time span. In gestural endings similar to that shown in Example 1, the performer is directed to remain involved with the musical event as it dissipates into quiet reverberations. The result is a dissolution of boundaries between sound and silence.

In the Japanese language, space and time are conceived as a single entity called ma. In art works, ma is an expressive force which fills the void between objects separated in time or space. The architect, Arta Isozaki describes ma as an aesthetic quality which occurs at the edge where two separate worlds meet. The way Takemitsu's delicate piano sonorities hover between the worlds of sound and silence is comparable to traditional Japanese expressions of changes in nature which Isozaki describes:

The fading of things, the dropping of flowers, flickering movements of mind, shadows falling on water or earth are the kinds of phenomena that most deeply impress the Japanese. The fondness for movement of this kind permeates the Japanese concept of indefinite architectural space in which a layer of flat boards, so thin as to be practically transparent, determines permeation of light and lines of vision. Appearing in this space is a flickering of shadows, a momentary shift between the worlds of reality and unreality. Ma is a void moment of waiting for this kind of change.5

Musical figures which begin with an initial accent and gradually die away are highly characteristic of Takemitsu's piano writing. When musical gestures end in this manner, the listener is less likely to hear the ensuing silences as partitions between events. Because such gestural endings lack a clear point of termination, one is more likely to hear the silence arising toward the end of such a figure as a direct outgrowth of the previous sound event. In this sense, the sound event draws silence into the piece as an active rather than passive element. It is possible to think of Takemitsu's long, decaying tones as hashi (bridges) projecting from the world of sound into that of silence. The moment of waiting for sound to become silence is in this way imbued with the quality of ma.

Unlike passive rests in most Western music which generally contrast musical actions, rests in Takemitsu's music represent musical actions. Virtually all silences in Pause ininterrompue refer back to a decaying sound event. These rests are, in a sense, nonrests, since the continuous stream of sounds and silences is never interrupted by a passive rest of terminating function. Silences are associated with motion, and are therefore rich in meaning. The title, Pause ininterrompue (Uninterrupted Rests) is in itself a paradox. Because motion is fundamental to our senses of perception, there can be no rest without motion. In Pause ininterrompue, a mood of restful intensity is created through continual nonrest. Takemitsu's title acquires poignant meaning through this paradox.

Because of the Japanese reverence for the beauty of nature, no strict distinction is made in traditional Japanese culture between the sounds of nature and the sounds appropriate for music.6 Takemitsu seems to view the musical tone as an element of nature to be treated with reverence. A fundamental feature of all Japanese philosophy is the respect for nature as something sacred, pure, and complete in itself. This aesthetic is reflected in Takemitsu's attitude toward musical tone, in which the absolute quality of tones assumes a dominant role in the formal structuring of a piece:

My musical form is the direct and natural result which sounds themselves impose, and nothing can decide beforehand the point of departure. I do not in any way try to express myself through these sounds, but, by reacting with them, the work springs forth, itself.7

In traditional Japanese music, a heightened sensitivity to the beauty of the movement and the individual sound event is reflected in Japanese attitudes toward timbre. In his article, "My Perception of Time in Traditional Japanese Music, Takemitsu describes the awareness of timbre as "the perception of the succession of movement within sound." He regards timbre as a dynamic temporal element which "arises during the time in which one is listening to the shifting of sound."8 Takemitsu discusses examples of traditional Japanese theater music in which instruments simultaneously follow differing temporal schemes, suggesting that the appreciation of such a discontinuous succession of musical events is rooted in the keen receptivity for timbral nuance among the Japanese.

Takemitsu compares "the philosophy of satisfaction with the single note to be found in the traditional music of Japan" with the discontinuous series of verses or scenes found in traditional poetry and picture scrolls. He states that in these works, the viewer or reader is invited "to provide his own version of its compositional intent or connection of meaning while contemplating the separate and independent significance of each verse or scene depicted."9 The Japanese sensitivity to the timbral beauty of isolated musical events is related to a general aesthetic sense which can discern a kind of unity among disparate elements in a work of art.

The opening of Takemitsu's second solo piano work, Piano Distance (1961), is shown in Example 2. Pianists must puzzle over what it is they are to do with a single, isolated tone marked "with feeling." If nothing more, this marking suggests that the single note, devoid of any linear context, can be an independent object of beauty. The marking tells the pianist to place this opening tone in motion in a deliberate and focused way, allowing its unadorned sound to become an event of significance.

Example 2. Takemitsu's Piano Distance, mm. 1-6

The composer reacts to qualities of sound imposed by the piano in a very direct way in Piano Distance. Rhythmic events in the piece correspond to the instrument's natural rate of decay, making the resonating characteristics of the piano an integral part of the composition. Emphasis is not so much on the motion of tones, but rather on tone itself, or, recalling Takemitsu's own words concerning timbre, "the succession of movement within sound." In this way, the sustained sound of a single pitch becomes an object revealed in time. This relates directly to Takemitsu's description of "the philosophy of satisfaction with the single note" which he describes in the traditional music of Japan.10

In Piano Distance and the second movement of Pause ininterrompue, bar lines mark off units of three seconds, providing the pianist with a regular point of temporal reference. Use of this notational device does not, however, result in any regular, audible metric structure. In addition to its extreme slowness, this potential for regularity is thwarted by musical figures which often extend beyond the bar line without downbeat accent. Since this long durational unit is not regularly subdivided with shorter note values, no audible metrical background results. It would be fair to say, then, that the durations in these pieces are projected against a background of silence itself.

Most Western music presupposes this background of silence. The metrical structure laid upon it cancels out static continuity, replacing it with a dynamic continuum of measured time. It is self-evident that a background of silence is undivided and without differentiation, unlike metrical backgrounds which depend on symmetrical division. The metrical background is, then, a closed environment. Removed from the external world, nothing of it extends beyond the beginning and end of the work. Conversely, an undifferentiated temporal background in a piece of music seems to enlist the undifferentiated temporal continuum which is all-embracing, common to all persons and things.11

In traditional Oriental philosophies, being suggests a connection with the infinite while action is temporal and temporary. An emphasis on being over doing has been fundamental in shaping traditional Eastern conceptions of time. In The Meeting of East and West, F.S.C. Northrop writes:

The Westerner represents time either with an arrow, or as a moving river which comes out of a distant place and past which are not here and now, and which goes into an equally distant place and future which are also not here and now; whereas, the Oriental portrays time as a placid, silent pool within which ripples come and go.12

In this Oriental image of time, a metaphor representing unchanging stasis, the silent pool, is contrasted with the Western image of directed motion represented by an arrow or river. The Oriental temporal model, however, is not completely devoid of vitality and movement. United with the image of an eternal, silent pool are transitory ripples of moment-to-moment events. In an apparent contradiction, the ripples come and go without disturbing the underlying stasis of the placid pool.

Nishida Kitaro writes that "beauty is the appearance of eternity in time."13 The experiential meaning ascribed to empty spaces or silences between sounds, whether in a modern piece by Takemitsu or a work from medieval Japan, may be interpreted as a metaphor for this Oriental concept of eternity. The presence of such a metaphor brings the present moment of experience into contact with something that has transcended time. This detaches the artist's subject from a spatial and temporal context, contributing to the feeling of impersonality perceived in much Oriental art.

These metaphors of static continuity, eternity and invariance are often juxtaposed with images which emphasize transient temporal qualities of life, growth and shorter natural cycle.14 When these contrasting opposites appear in an art work, time is mutually represented as foreground and background. In providing a framework within which finite action and timeless eternity coexist, the art work becomes a model of time itself.

A reverence for the divinity inherent in all things, finite and eternal, can be seen in the Haiku poetry of the sixteenth-century Zen Buddhist monk, Basho:

An ancient temple pool;

Jump of a frog;

The sound of water.

In his book, Unreality and Time, Robert S. Brumbaugh points out that in Basho's poetry we often find small finite beings superimposed against a "background of eternity."15 The ancient pool, a metaphor for continuity and eternity, is contrasted with the sudden impulse of the frog. The union of these two elements creates profound imagery of sound and motion. The poem, like all Zen-inspired arts, is imbued with freshness, liveliness and spontaneity, yet also invites quiet contemplation.

Certain types of Japanese painting, including the sumie or black ink paintings of the sixteenth century, leave a large portion of the space empty. This openness, objectified by the artist, is like a window into an endlessly extended visual world. It suggests a "background of eternity" similar to that found in the Basho example. Here, however, the metaphor is conceived more in terms of space than time. Victor Zuckerkandl observes that a small object in an Oriental painting can draw boundless space into an image, instilling the surrounding emptiness with meaning:

[T]he result is a composition made up of a trace of the objective and a great deal of emptiness, and this emptiness, which just before was not yet anything, is now something: space. The artist's purpose from the beginning was not so much to copy a thing as to form a whole out of a minimum of "thing" and a maximum of emptiness, to shape space; the thing becomes his occasion for letting the surrounding space become manifest, for taking it in his hand, as it were—through the thing he shapes the space beyond the thing. What the beholder perceives is, then, not simply space, but a space formed and organized in a particular way, a space image."16

In traditional Japanese poetry and visual arts, the most humble of subjects may be united with metaphors of timeless eternity, symbolizing the divinity of all things. This juxtaposition of the finite and the infinite, which Nishida Kitaro has called the unity of opposites, generates an element of vitality found in many Japanese art works. This juxtaposition of opposites does not appear as a simple duality of thesis and antithesis as found in Western art forms. It is not a tension of conflicting forces directed toward a goal of resolution, but rather, it is a subtle dynamic presence which never subsides, adding continual vitality to traditional works of Japanese art.

Although Nishida Kitaro is a modern Zen poet and philosopher, his idea of reality defined through a unity of opposites can be traced back to the teachings of the thirteenth-century Japanese Zen master, Dogen, who writes, "Time is the radiant nature of each moment; it is the monumental everyday time in the present."17 Reality, according to Dogen, is the stream of natural events occurring in the absolute present superimposed against a background of timeless eternity. It consists of motion and its opposite, occurring in time. Paradoxically, it is a concept of stasis defined by motion.

Takemitsu's music illustrates the Japanese aesthetic of ma operating through a unity of opposites. Nishida Kitaro states that "the individual forms the environment, and the environment forms the individual."18 In Takemitsu's music, individual tones form the environment, which is silence or time itself. The empty void of eternal time cannot be comprehended, but when sounds serve to frame an interval of time, then meaning is perceived. In the music of Takemitsu, sounds give meaning to silence; finite temporal markers suggest an awareness of eternal time.

In the temporal imagery of traditional Japanese arts, moment-to-moment events are superimposed against a static background; being and becoming are recognized as contraries which mutually define each other. Through the decaying reverberation of the piano's tone, Takemitsu creates a metaphor for the fluidity and impermanence of the physical world. Musical gestures in Takemitsu's music which begin with an initial accent and gradually fade away have the effect of enlisting the surrounding silence, so that ultimately the static sonorous background becomes linked to a background of objectified silence.

In Takemitsu's later piano works, a stream of local musical events may be superimposed against a static background of sustained octatonic sonorities.19 Although octatonic pitch structures can be found in Takemitsu's earliest published piano works, he begins to utilize octatonicism as a global force for pitch organization only in his third solo piano piece, For Away (1973). This new, more thorough reliance on octatonicism may be due in part to new problems in pitch structuring as musical events are compacted in a thicker, more melodically continuous texture.20

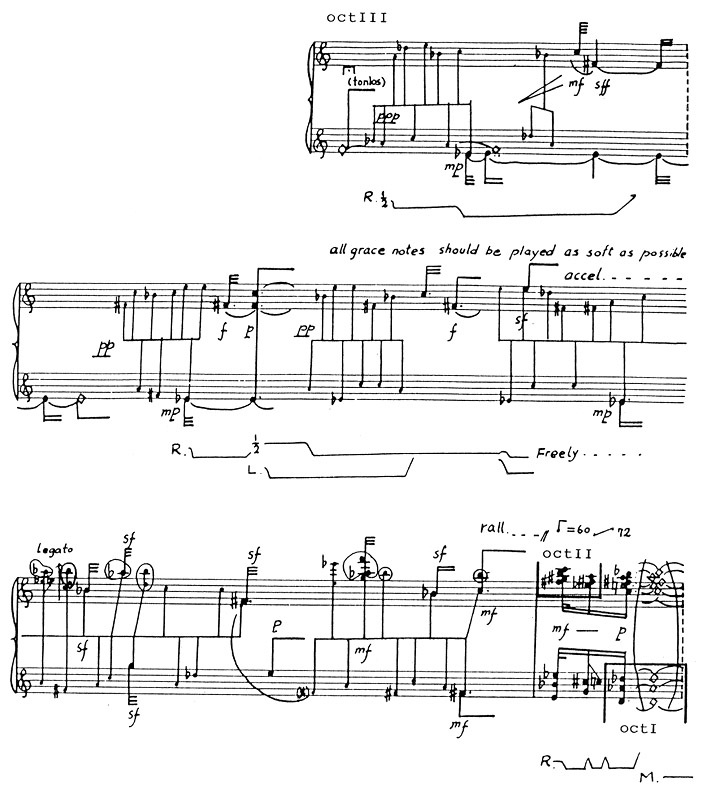

The passage from For Away shown in Example 3 features long streams of grace notes which form the octIII septachord {A  C

C

E

E  }.21 The pitch-class needed to complete the octatonic collection, G, is reserved for the highest note in the lower score near the ending of m. 28. This event is marked sforzando for added emphasis.

}.21 The pitch-class needed to complete the octatonic collection, G, is reserved for the highest note in the lower score near the ending of m. 28. This event is marked sforzando for added emphasis.

Example 3. Takemitsu's For Away, mm. 27-29

The triitone figure on  4/C5 and the semitone dyad

4/C5 and the semitone dyad  4/E5 are the only pitch materials given specific rhythm values and dynamic markings in the opening of the passage. These figures, and the general emphasis on pitches which are common to the octIII collection, can be traced to the opening measures of the piece. New pitch materials with specific rhythm values and dynamic markings are gradually introduced in the later part of m. 28, forming a series of semitone dyads:

4/E5 are the only pitch materials given specific rhythm values and dynamic markings in the opening of the passage. These figures, and the general emphasis on pitches which are common to the octIII collection, can be traced to the opening measures of the piece. New pitch materials with specific rhythm values and dynamic markings are gradually introduced in the later part of m. 28, forming a series of semitone dyads:  4/B5, G5/

4/B5, G5/ 5,

5,  4/F6,

4/F6,  4/B5. Non-octIII pitches are circled in Example 3.

4/B5. Non-octIII pitches are circled in Example 3.

Pitch saturation is gradually completed, culminating in the appearance of F6 near the end of m. 28. Reserved for the highest melodic peak in the section, pitch-class F is wholly fresh to this section, forming a biting dissonance with the lowest note in the gesture,  4. The dense chords which follow exceed the boundaries of a single octatonic collection. With the octIII grace note figuration marked to be played ''as soft as possible," in a very literal sense these semitone dyads are highlighted against a static octIII background. Viewed in this manner, the passage clearly exemplifies Takemitsu's practice of building up a fully chromatic texture from an octatonic base.

4. The dense chords which follow exceed the boundaries of a single octatonic collection. With the octIII grace note figuration marked to be played ''as soft as possible," in a very literal sense these semitone dyads are highlighted against a static octIII background. Viewed in this manner, the passage clearly exemplifies Takemitsu's practice of building up a fully chromatic texture from an octatonic base.

The way that Takemitsu's music hovers between octatonic references and total chromatic saturation is one manifestation of the composer's ability to create a powerful and original expression through a unity of apparent contradictions. Poised in perfect balance between opposing musical and cultural idioms, his elegant music achieves a powerful, quiet intensity. Strongly identifying himself both as Japanese and a composer in the Western sense, Takemitsu projects in his music a maturity of personal expression which transcends the hybrid styles of previous Japanese composers.

In traditional Japanese arts, an effort is made to draw infinite time and space into a work, objectifying it with boundaries defined by finite objects. In transforming this void into something tangible and meaningful, the artist creates the aesthetic quality of ma. Using sparse textures which begin quietly and fade away into nothingness, Takemitsu draws the surrounding silence into the music. An intrinsically Japanese model of time itself is created in the juxtaposed metaphors of time and timelessness, as relatively autonomous sound events dissolve into a silence imbued with meaning.

Projecting finite sounds against an infinite temporal background, Takemitsu creates a tension of opposites analogous to that often found in works of traditional Japanese art. In the composer's own words,

The most important thing in Japanese music is space, not sound. Strong tensions. Space: ma: I think ma is time-space with tensions. Always I have used few notes, many silences, from my first piece.22

If the edge where two different worlds meet can be said to be infused with the quality of ma, then Takemitsu's music is indeed rich in this quality, with tone structures hovering between the sound worlds of octatonicism and total chromaticism as delicate textures of decaying sound dissolve the boundaries between sound and silence. Takemitsu's music achieves poetic elegance through an aesthetic balance of contraries—of Eastern ideals and Western technique, of structural integrity and pure unencumbered sonority, of sound and silence equally embued with expressive meaning.23

1Toru Takemitsu, "A Mirror and an Egg," Banff Letters, trans. Daniell Starr and Syoko Aki (Spring 1985), 20.

2See Dana Wilson, "The Role of Texture in Selected Works of Toru Takemitsu" (Ph.D. diss., University of Rochester, 1982), and Jonathan Chenette, "The Concept of Ma and the Music of Takemitsu," paper presented at the National Conference of the American Society of University Composers, University of Arizona, March 1985. TMs [photocopy] provided by the author.

3In discussing aesthetic qualities which are characteristically Japanese, it would be a mistake to suggest that such qualities are entirely without counterparts in the West. On the contrary, there are points of confluence in modern Western music and traditional Japanese art which make Takemitsu's time and place in the history of world music particularly interesting. For example, the discontinuous succession of isolated musical events presented in much of Anton Webern's music produces an effect which Ligeti describes as the "spatialization of the flow of time," a quality which has much in common with the temporal structures of traditional Japanese arts discussed in this study. See George Rochberg, "The Concepts of Musical Time and Space," in The Aesthetics of Survival (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1984), 111-12. For a discussion of parallels in Oriental music and the music of Webern, see Chou Wen-Chung, "Asian Concepts and Twentieth Century Composers," Musical Quarterly 57 (1971), 214; and Wilson, "The Role of Texture in Selected Works of Toru Takemitsu," 30-31.

4Toru Takemitsu, liner notes "Toru Takemitsu: Miniatur II," Japanese Deutsche Grammophon, MG2411.

5Arta Isozaki, "Ma: Japanese Time-Space," The Japan Architect 54 (1979), 78.

6Eishi Kikkawa, "The Musical Sense of the Japanese," Contemporary Music Review 1/2 (1987), 86. For an interesting perspective on Japanese values and thought processes related to language and the sounds of nature, see Steve Earle, "Does Nature Speak in Japanese?" East-West Journal (1979), 64-73.

7Toru Takemitsu, quoted in liner notes "Piano Music of Takemitsu," Decca Head 4.

8Toru Takemitsu, "My Perception of Time in Traditional Japanese Music," Contemporary Music Review 1/2 (1987), 10.

9Ibid., 11-13.

10Ibid., 10-12.

11Northrop discusses an undifferentiated continuum vs. transitory differentiations as time components in The Meeting of East and West (New York: Macmillan Company, 1946), 376-83.

12Ibid., 343.

13Nishida Kitaro, Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness (Tokyo: Maruzen Co., Ltd., 1958), 40.

14Robert S. Brumbaugh, Unreality and Time (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1984), 133.

15Ibid., 30.

16Victor Zuckerkandl, Sound and Symbol: Music in the External World, Bollingen Series, No. 44 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), 257-58.

17Eihei Dogen, Shobogenzo [The Eye and Treasury of the True Law], trans. Kosen Nishiyama and John Stevens (n.p.: Daihokkaikaku, n.d.), 68; see also Jeremy Rifkin, Time Wars: The Primary Conflict in Human History (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1987), 116.

18Nishida, Intelligibility and the Philosophy of Nothingness, 164.

19The octatonic collection is composed of alternating whole tones and semitones. As a synthetic scale with symmetrical properties, it can be transposed to form only three nonduplicating collections:

octI D E F G B

octII B C D F A

octIII C E G A

OctI, octII, and octIII are abbreviations representing octatonic collections as labeled by Peter van den Toorn in The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 50.

20See, for example, the dense chords based on octatonic collections in the second movement of Pause ininterrompue at mm. 24, 34, 47 and 48. For striking examples of octatonic surface features in Takemitsu's more recent piano piece, Rain Tree Sketch (1982), see the octatonic figuration at mm. 14-31 and the succession of chords at mm. 40-41.

21The silently depressed F4 at m. 27 does not interfere with projection of octIII. In performance, the strings of F4 strongly resonate with C5, heightening emphasis on C5 evident throughout the passage.

22Toru Takemitsu quoted in Fredric Lieberman, "Contemporary Japanese Composition: Its Relationship to Concepts of Traditional Oriental Musics" (M.A. thesis, University of Hawaii, 1965), 140-41.

23The author wishes to thank Toru Takemitsu for his useful comments on ideas presented in this paper. The author gratefully acknowledges Editions Salabert for permission to include excerpts from the following scores:

Pause ininterrompue

Copyright 1962 by Editions Salabert, Paris. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Editions Salabert.Piano Distance

Copyright 1961 by Editions Salabert, Paris. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Editions Salabert.For Away

Copyright 1973 by Editions Salabert, Paris. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Editions Salabert.