In the preceding paper, Elliott Antokoletz provides a structural analysis of the Fifth Door Scene in Bartók's opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle. Antokoletz describes the scene's organization as an "overall extended binary form" based on the text's quatrain-like folksong structure. He suggests that the text structure is projected onto several formal levels of the scene with increasing irregularity, and proposes a structural plan that reflects this binary but irregular form.2 Antokoletz's premise regarding the importance of the text as a structure-determining element in this scene is accurate. But as he delves into the process of pitch set interaction between the characters of Bluebeard and Judith, his attention is drawn away from the continued fundamental importance of the text as a structural determinant. The concentration of his analytical efforts in this direction ultimately causes him to conclude that the scene becomes extended and irregular as it progresses.

If, instead, we attempt to trace the regular, quatrain-like structure of the text itself in Bartók's musical setting, an interesting correspondence emerges: the structure of the Fifth Door Scene directly reflects the structure of its text. In other words, the regular pattern of lines that characterizes the text's quatrain-like structure may be perceived as providing a direct means of organization for the musical setting. When Antokoletz writes that "[t]he symmetrical quatrain structure. . . serves as the point of departure for a more complex structural development. . . ," he is suggesting that the structure of this scene becomes increasingly independent of its text. This is not the case. Bartók's Fifth Door Scene falls into regular, reiterated sections that exhibit essentially the same structure—from beginning to end—as the text on which the scene is based.

The text divides into three structurally equivalent sections, each comprised of fourteen or twelve lines organized through a repeating quatrain-like pattern. Bartók's music supports a structural analysis based on this organizational pattern. Tempo and meter changes, the location of fermati, and the presence or absence of significant musical motives all demonstrate that Bartók himself was aware of the regularity of the text's structure and used it as a point of departure for his music.

Throughout the opera, the basic building block of the text is the eight-syllable line. As Antokoletz notes, this is one of the isometric stanzaic patterns found in the oldest of the Hungarian folk melodies. In the Fifth Door Scene, perhaps more consistently than elsewhere in the drama, these individual lines may be grouped into folk-like quatrain structures. At the scene's beginning, the dialogue between Bluebeard and Judith is comprised of four-line stanzas: Bluebeard describes the vast splendor of his domains for three lines, and Judith responds with one. This pattern repeats. In the next four lines, Bluebeard offers his magnificent domains to Judith, assuring her of a bright future therein. When, in response, Judith perceives blood-red clouds gathering on the horizon, a sudden change in mood occurs. Her two-line interjection creates a natural break in the text.

These first fourteen lines form a distinct section of the text in which Bluebeard and Judith (and by extension, the audience) focus on the Fifth Door and its revelations. Dialogue within this section is further divisible into individual units of four or two lines each that share some common psychological or dramatic element, as indicated above. Division of the text in this manner appears to be an inherent feature of the text itself. The existence of discernible quatrains and couplets reflects the influence of Hungarian folk elements on the librettist Balázs.3

Subsequent text in the Fifth Door Scene confirms the existence of an organized line structure. The second section focuses on the dialogue between Judith and Bluebeard. Judith's insistent requests to have the remaining two doors opened are countered by Bluebeard's equally strident desire to thwart her. The third section is distinguished from the second by its gradual shift in emphasis to the unopened Sixth Door and by a noted psychological difference in Bluebeard's character, apparent from the section's beginning. The entire text of the scene is thereby divided into three sections as a result of shifts in dramatic content or focus: in the audience, our attention is drawn first to the Fifth Door, then to Bluebeard and Judith themselves, and finally, to the Sixth Door.

A basic pattern of 4,4,4,2 lines in the first section is confirmed by its reiteration in the second section. In the third section, the 4,4,4,2 line pattern is present, but partially obscured. Here, the fractured nature of Judith and Bluebeard's dialogue complicates perception of its inherent structure. In addition, only twelve lines remain to the end of the scene, when fourteen would be required to complete the pattern.4 The presence of a 4,4,4,2 pattern is suggested, however, at both the beginning and end of the section. The first four lines form a subsection based on the dialogue between Judith and Bluebeard; the last two lines in the scene ("One more key is all I give you. /Judith, Judith, leave its secret!)5 are analogous to the final couplet in the two preceding sections. With these two groups of lines anchoring either end, it is then a matter of combining intermediate lines and half-lines into recognizable groups.

Bartók's musical setting of the text reinforces the idea that a repeated 4,4,4,2 pattern of lines forms the structural foundation of the Fifth Door Scene. Divisions between the three principal sections are marked unambiguously; transitions are articulated through changes of tempo, meter, and orchestration, in addition to new or transformed musical material. For example, the transition from Section A to Section B at No. 79 is marked by an abrupt shift in tempo and meter (Section A: 4/4 Larghissimo  = 66; Section B: 3/4 Vivace

= 66; Section B: 3/4 Vivace  = 80).6 The simultaneous ritardando molto and crescendo molto in the orchestra one measure before No. 79 emphasize the structural break.

= 80).6 The simultaneous ritardando molto and crescendo molto in the orchestra one measure before No. 79 emphasize the structural break.

At No. 85, the transition from Section B to Section C is marked by a similar shift in tempo and meter (Section B: 2/4 Andante  = 76; Section C: 4/4 Agitato molto

= 76; Section C: 4/4 Agitato molto  = 160). This transition, too, is emphasized by a poco ritardando and dynamic marking contrast. To make it clear that a structural break is intended, Bartók adds a brief fermata over the bar line.

= 160). This transition, too, is emphasized by a poco ritardando and dynamic marking contrast. To make it clear that a structural break is intended, Bartók adds a brief fermata over the bar line.

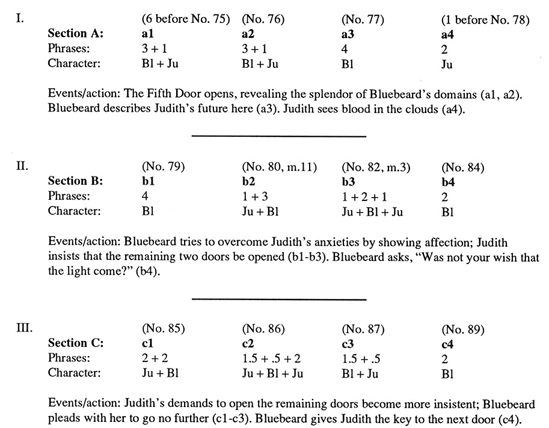

The structure of the Fifth Door Scene, as reflected through its text, is given in Diagram 1. (Compare with Ex. 9 in Antokoletz's article).

Diagram 1

Structure of Duke Bluebeard's Castle

Fifth Door Scene7

Three basic features of the scene's structure may be observed:

1. The scene is divided into three sections. Antokoletz recognizes this division, but instead of viewing the sections as three successive, integral sections, he proposes that the third section (his Section B) acts as an "extremely expanded subsection" replacing the two missing lines at the end of his Section A2. This interpretation is discussed below.

2. Each of the three sections exhibits the same fundamental structure of 4,4,4,2 lines. The single exception is found toward the end of the scene, in subsection c3, where two lines of text are absent. Antokoletz recognizes the existence of a quaternary pattern of lines; in his analysis, however, the pattern, once established, is never completely repeated. It acts as a structural basis from which Bartók creates variants that increase in size and frequency as the scene progresses.

3. As the scene progresses, the dialogue becomes increasingly fragmented without disrupting the regularity of the underlying line structure. Perception of the underlying 4,4,4,2 line pattern in Section C is difficult. Clipped phrases, reflecting the intensified emotions of Judith and Bluebeard, obscure the relationship between lines of text. Antokoletz reminds us that, after the first four lines in this section, the text remains octosyllabic but becomes ambiguous in relation to line structure. This ambiguity can readily be reduced by grouping the text into subsections comprised of either four or two lines, in a manner consistent with the previous two sections.

Antokoletz's approach to the structural analysis of the scene is essentially music-oriented. Mine is text-oriented. To a large extent, this difference in approach manifests itself in the way we resolve and explain conflicting forces that create ambiguity in the scene. When structural ambiguities are encountered, I resolve them in favor of the text, seeking the same regularity I perceive in the text; Antokoletz resolves them on musical grounds, based on musical relationships and events, which inevitably results in a de-emphasis of the text as a structural determinant at these points of ambiguity.

His tolerance for irregular structure is encouraged by his considerable knowledge of Bartók's compositional background. Of the opera as a whole, Antokoletz writes,

Bartók's new. . . musical language is . . . in keeping with the composer's understanding of the folk-music structures themselves. . . much of the melodic and harmonic fabric is generated by means of modal elaboration and transformation, a principle that appears to be derived from the process of thematic variation found in the folk-music sources.

In his analysis of the Fifth Door Scene, Antokoletz justifies his perception of its extended, irregular structure with an appeal to the principle of thematic variation in folk song sources. He transfers this concept of variation to a larger, structural level. In this way, variations in structure are not only justified, but to be expected.

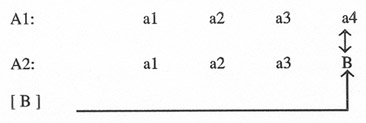

In labeling the three main sections A1, A2, and B, Antokoletz emphasizes what he calls the "overall extended binary form" of the scene. The first two sections are similar to each other in their structure but the third, with its "extremely contrasting and developmental character," acts as an expanded subsection that replaces Section A2, Part a4. The relationship between the sections as he describes them is illustrated in Diagram 2.

Diagram 2

Interrelationship of the Scene's Three Sections in Antokoletz's Analysis

To Antokoletz, the third section acts not so much as a third statement of a basic structural pattern, but more as a developmental elaboration of a corresponding subsection in Section A1. There is some justification to this idea. Bartók's music to the third section does act, in a sense, as what Antokoletz labels, ". . . a macroscopic structural reflection of Judith's reference to blood in the fourth phrase of [Section A1] . . ." Bartók develops the semitonal blood motive in this section with marked intensity. Musically, it is similar to subsection a4 in that each is composed using the semitonal blood motive. In order for Antokoletz's Section B (my Section C) to act as replacement for a missing a4 subsection, however, this subsection must actually be absent. It is not. As shown in Diagram 1, Section B (Antokoletz's A2) is in full possession of fourteen lines that fall into the 4,4,4,2 pattern. The last subsection (my b4) is not absent. Antokoletz has rearranged the fourteen lines in this section to leave the final subsection empty; once missing, the last subsection may then be replaced, and expanded upon, by the entire B Section.

Determination of the exact beginning and ending points for individual quatrains and couplets within each section is not always a simple matter. While clearly articulated for the most part, it is not unusual for these subsections of text to exhibit an ambiguous relationship with their musical setting, especially in Section C. On this issue, Antokoletz's interpretation often varies from my own. Two examples illustrate the results of our different approaches.

1) In Section A, thrilling parallel chords burst forth in the orchestra to introduce, in turn, subsections a1, a2, and a3. Music punctuates the dialogue, dividing it into four-line sections. Each subsection is introduced by the parallel chords in the orchestra and concluded by the continuation of these chords at the beginning of the next subsection. The beginning of subsection a4, however, appears ambiguous. Antokoletz, who tends to attribute structure-determinative status to musical events, hears the recurrence of the parallel orchestral chords at one measure after No. 78 as the beginning of a4. This view has the advantage of consistency: the same orchestral figure introduced each of the preceding three sections. It minimizes, however, the importance of Judith's reference to blood that occurs in her line a measure earlier, and results in Judith's two-line phrase being split between two structural subsections, one consisting of only a single line (see a3 and a4 in his diagram).

Dividing Judith's reference to blood in this manner conflicts with the pattern established by her similar references in Scenes Three and Four, which are sung in two-line groups preceded by orchestral interjections of the semitonal blood motive. Bartók underscores the structural unity of these two lines in Scene Five by introducing the semitonal motive in the orchestra at one before No. 78, just prior to the point where Judith notices the blood in the clouds. Section a4 is initiated, therefore, by the intrusion of a  into an E major chord at one before No. 78. The conflict between the major third E -

into an E major chord at one before No. 78. The conflict between the major third E -  and minor third E -

and minor third E -  forms the semitonal blood motif. When the parallel orchestral chords return at one after No. 78, they are now subdued and in a minor mode, beginning on an F minor triad and concluding four measures later on a

forms the semitonal blood motif. When the parallel orchestral chords return at one after No. 78, they are now subdued and in a minor mode, beginning on an F minor triad and concluding four measures later on a  minor triad. The somber character of the orchestral chords at this point contrasts considerably with their brilliance in the preceding three subsections. This orchestral phrase is not the beginning of a new structural subsection, but a subtle musical reflection on how, for Judith, the magnificence of Bluebeard's realm is forever lost when she sees blood in the clouds' shadow. Bartók has transformed the character and meaning of a musical motive. In doing so, he alters its structural function.

minor triad. The somber character of the orchestral chords at this point contrasts considerably with their brilliance in the preceding three subsections. This orchestral phrase is not the beginning of a new structural subsection, but a subtle musical reflection on how, for Judith, the magnificence of Bluebeard's realm is forever lost when she sees blood in the clouds' shadow. Bartók has transformed the character and meaning of a musical motive. In doing so, he alters its structural function.

2) A second example of how aural perception of musical structure can conflict with the regular underlying structure of the text may be found at the end of the first quatrain (b1) in Section B. In my interpretation, the ending point of this subsection is located not at No. 80, but at the conclusion of Bluebeard's line "let my grateful arms embrace you," six measures after No. 80. At first glance, this seems to overlook the prominent grand pause and fortissimo orchestra re-entry directly at No. 80. This point of interruption might represent a more logical structural break. Recognizing this, Antokoletz indicates, at this point, the beginning of a new subsection.

Bluebeard's line that comes after this strong musical interjection, however, is psychologically unified with his preceding three lines celebrating Judith's sunny touch. The orchestral outburst at No. 80 is a deliberate rupture designed by Bartók to emphasize Bluebeard's stage direction at that point—opening his arms to Judith. The sudden crash of orchestral sound allows time for Bluebeard to open his arms, but more importantly, it focuses the audience's attention on the fact that Bluebeard has his arms open to Judith. In a drama imbued with symbolism at every turn, Bartók is drawing our attention to this most symbolic of gestures. At this last moment of hope before Judith moves irrevocably to her doom, Bluebeard wishes to reconcile and love.

As soon as this gesture is accomplished, the music resumes in the same tempo and character as before (Vivace  = 80). After No. 80, Bluebeard sings in the same style and with identical pitch content. In this way, Bartók underscores his basic understanding of the textual unity of the first quatrain (b1). The orchestral interruption is best interpreted as a musical embellishment to a stage action that temporarily draws the audience's attention to a symbolic gesture made by Bluebeard. Bluebeard's four lines of text at the beginning of Section B form a single structural unit that stretches across the musical interruption at No. 80 instead of being separated by it. An ancillary result of this analysis is that the subsequent eight lines, starting with Judith's pointed observation that two doors remain unopened, form two recognizable quatrains unified in dramatic purpose and framed—not accidentally—by the visual symbol of Bluebeard's open arms.

= 80). After No. 80, Bluebeard sings in the same style and with identical pitch content. In this way, Bartók underscores his basic understanding of the textual unity of the first quatrain (b1). The orchestral interruption is best interpreted as a musical embellishment to a stage action that temporarily draws the audience's attention to a symbolic gesture made by Bluebeard. Bluebeard's four lines of text at the beginning of Section B form a single structural unit that stretches across the musical interruption at No. 80 instead of being separated by it. An ancillary result of this analysis is that the subsequent eight lines, starting with Judith's pointed observation that two doors remain unopened, form two recognizable quatrains unified in dramatic purpose and framed—not accidentally—by the visual symbol of Bluebeard's open arms.

***

The existence of a predetermined structural framework in the Fifth Door Scene has considerable implications for further study of Bluebeard's Castle. To date, little scholarly attention has been brought to bear on the issues of local structure in this remarkable opera. Several investigations have illuminated, with varying degrees of success, some of the large-scale structure that binds the Prologue, Seven Doors, and Epilogue into one continuous sectional arch form.8 Antokoletz's article is the first systematic exploration of aspects of local structure and design. Yet our understanding of organization within individual scenes remains, at best, incomplete. Bartók created an overall plan for the opera that was organized on a broad architectural level; there is no reason to believe that other levels of equally sophisticated organization do not exist within individual scenes.

1This essay is a response to the reading of a pre-publication copy of Antokoletz's article on Bluebeard's Castle. His article was made available to me during the Spring of 1990, when I had the opportunity to sit in on a course on the music of Bartók which Antokoletz taught at the University of Texas at Austin. Antokoletz's remarks concerning this essay have contributed greatly to its present form.

2In Antokoletz's paper, the analysis of the Fifth Door Scene represents only a fraction of his argument. The basic substance of his paper is concerned with pitch-set identification and the modal or bimodal development of musical material throughout the opera, as these elements relate to structure and design. In singling out the Fifth Door Scene for discussion, I urge the reader to bear in mind that any criticism directed at this one part of his paper does not reflect my opinion regarding Antokoletz's paper as a whole, which is a significant contribution to the existing literature on the opera.

3In his own words, Balázs drew from the raw material of the Székely folk ballads to create the libretto. His purpose was to form "modern, intellectual inner experiences." Cited in Siegfried Mauser, "Die musikdramatische Konzeption in 'Herzog Blaubarts Burg.'" Musik-Konzepte 22, H.K. Metzger and R. Riehn, eds. (Munich: November, 1981), 71.

4Because of its two absent lines, the structure here may be more accurately rendered as 4,4,[4],2 lines. It is possible that the sixteen syllables comprising the missing two lines are symbolically represented in the orchestra. At the end of Section C, starting at No. 89, Bluebeard gives Judith the Sixth Door key. As he does so, sixteen muffled rhythmic pulsations are heard in the orchestra, in a pattern of eight, seven, and one beats. Antokoletz describes a similar orchestral completion of missing syllables occurring near the beginning of the opera.

5English translations used in this essay are those of the American writer Chester Kallman, who is perhaps most remembered for his coauthorship, with W.H. Auden, of the libretto for Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress. Kallman's translation is published in the liner notes accompanying Istvan Kertesz' 1966 recording of Bluebeard's Castle (London OSA 1158). It faithfully preserves the eight-syllable metric content of each line.

6All numbers in this discussion are those found in the first edition of Bluebeard's Castle, published in piano-vocal format by Universal in 1921 (Universal-Edition Nr. 7026).

7In the diagram, each line of text is accounted for under the heading "phrases." Each of these lines, of course, contains eight syllables; hence, in Section c2, the rather cryptic looking "1.5 +.5 + 2" translates into 12 syllables (1.5 lines) for Judith, 4 for Bluebeard (his interjections "Judith, Judith"), and another 16 syllables (or 2 full lines) for Judith, for a total of 4 × 8, or 32 syllables. Such precise numerical manipulation is permitted only because of the strict preservation of the octosyllabic line. The character singing each line is shown directly under the numbers of lines which he or she sings. The starting points of each subsection are indicated, when possible, as the starting point of the musical area within which the text occurs.

8See Sándor Veress, "Bluebeard's Castle," Tempo 13 (1949), 32-38 (Pt. I); 14 (1949-50), 25-35 (Pt. II); and Siegfried Mauser, "Die musikdramatische Konzeption in 'Herzog Blaubarts Burg,'" 69-83. The M.A. thesis of Sally Ann Rhodes, "A Music-Dramatic Analysis of the Opera Duke Bluebeard's Castle by Béla Bartók" (Eastman School of Music, 1974), was not examined for this essay.