Students in many ear training classes are too often insulated from realistic and musical learning experiences. Most ear training involves the teaching of harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic perception by means of dictation. The music used in this dictation is usually played at a piano and divorced of context—a chord progression played as block chords in the middle register of the piano at a dynamic level of mezzo forte and in a uniform, heterogeneous rhythm. In melodic dictation the student is expected to transcribe a melody which may again be similar rhythmically, dynamically, and in terms of register to the above mentioned description of the harmonic dictation exercise. Often these melodies are composed by the instructor in an effort to test the student's ability to perceive specific intervals. The student after a period of time, for example, may be expected to hear, say, a minor seventh, a tritone, or a major sixth, frequently within a brief three or four phrase melody. Some have referred to this most unmusical endeavor as "hearing specific intervals within context." At best, however, this may be likened to a Reader's Digest-like realization of an entire piece; hit all of the high points, spare the fluff, and be done with it. If one wanted to test for many specific intervals one might as easily play an all-interval twelve-tone row, such as that found in Alban Berg's "Lyric Suite." Then, when the student could correctly transcribe this melody, the instructor would be ensured that the student had a mastery of all of the intervals, and within context! (Of course this last point is slightly exaggerated.)

The student may benefit from occasional harmonic, melodic and rhythmic dictation drills at the piano in the same manner that a performer does from the practicing of scales, arpeggios, and etudes. And as the performer uses scales and exercises only as a means to an end, so too should the student concentrate on "real" music, that is, the use of recorded examples of diverse styles, periods, instrumentation, harmonies, melodies, and tempi, and use non-contextual musical drills only as a secondary means for acquiring the requisite transcription skills. The student who only listens to music played on the same instrument (the piano, computer, etc.), at the same tempo, register, and dynamic level, and out of context will not be equipped to transcribe live or recorded music or music of styles to which he/she is unaccustomed.

In order to develop the essential skills of music perception and transcription, the student must work extensively outside of the classroom. Ear training labs, usually featuring numerous taped harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic dictation exercises, may be helpful. Many ear training labs, in addition to tapes, now feature interactive computer assisted instruction programs which allow a student to receive individualized instruction and hear varied material at graded levels. Many of these programs allow the student to focus upon deficiencies, progress to an appropriate level when the preceding level has been mastered, and keep track of the amount of time spent on the computer. Presently, the disadvantages of the computer as an ear training accessory/pedagogue are centered around the available software and include limited tone color capacities, rhythmic rigidity, brevity of musical excerpts, and, as in the case of dictation from the classroom piano, the use of unrealistic and homogeneous musical material.

Regardless of the successes or shortcomings of the ear training lab, the student must practice these skills in situations outside of the music school. One of the best means of motivating students to listen analytically in an extra-academic setting is to require them to transcribe the music to which they are constantly exposed. A student, for example, hears Diet Coke, Burger King, Doublemint gum, U.S. Army, Miller, and Budweiser jingles each week, as well as television theme songs, music from M-TV and VH-1, radio stations, car horns and church bells. All of these pitch/music sources provide more and diversified opportunities for transcription, perception, and analysis than those which the student faces in the music theory classroom or lab. The thought that a plethora of educational experiences constantly confronts the student, and indeed such a rich means to an end, that is, twenty-four potential hours of dictation practice, probably has not occurred to the student or the professor. Many music students surprisingly do not make the connection between that which takes place in the classroom or lab with the transcription of music from other sources. Students who have been taught using only the piano or an unimaginative computer have often responded with animosity or confusion when first asked to transcribe recorded music or music which has not been played at the piano in the sterile manner mentioned above, objecting that they could transcribe the music if it were played on the piano, played slower, played louder, etc. Students can and will overcome these problems if they are consistently challenged to transcribe and analyze varied types of music in context. Most students, for example, have heard the common chimes theme shown here but surprising few can correctly notate it.

C4- 3-

3-

3

3-

3-C4-

3

Recordings of rock music, as well as country, jazz, and other popular styles, can be used effectively as a resource in the teaching of classical music theory and ear training. (For convenience, the term "rock music," will be used throughout to mean all types of non-Classical Western music.) Whether rock music is an "art" form deserving of observation and analysis seems to have been answered in the affirmative. Witness the number of music appreciation textbooks discussing the subject, or the significant and philosophically varied members of the Classical music world who have praised and continue to praise rock music as an important form—Leonard Bernstein, Philip Glass, and John Cage, to name a few. (John Rockwell, in The New York Times, January 19, 1986, claimed that the impact of rock videos upon the composition, staging, and content of Classical opera is profound and that the two will become more closely related in the future.) Most college students grew up listening to rock music. It is the music that they like best and hear most often. It is their "folk" music. Whether a student is exposed to Classical music later and begins to like it or dislike it, the student will probably continue to enjoy rock music. In addition, many students will work harder at acquiring the necessary skills for melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic dictation if some of the music that they are studying is drawn from this body of music. A carefully selected collection of rock music works in the Classical music ear training course will be very helpful for the student's acquisition of skills in music perception and analysis. Studying Classical theory and ear training can seem more germane when the musical experience can be applied outside of the classroom; for example, when a student discovers the parallels between harmonic progressions and melodic and rhythmic structure in Classical and rock music, and that analytical techniques and views from one domain can be used in the other to yield more information about both styles. There are countless examples of parallels between rock and Classical music in their technical content. Such parallels can be helpful in emphasizing a point. When parallels do not exist, the students also benefit in that they are better equipped to understand the technical differences between the two types of music.

The student who aspires to be a public school music teacher needs to be familiar with rock music. Students will expect him/her to be familiar with "their" music—to discuss it, teach it, and transcribe it when necessary. In fact, many young musicians have become interested in Classical music only after initially experiencing rock music, then studying theory and noticing the points of coincidence. Classical music offers a longer history of works and a relatively well developed corpus of theoretical ideas and analytical devices to entice the student. Adept theory teachers, at the college, high school, or elementary levels, can "convert" some students to Classical music if the teacher can speak the student's first language, that is, when he/she knows the literature and theoretical substance of rock music.

As mentioned above, one finds many parallels between rock and Classical music. The teaching of voice leading and the intelligent construction of harmonic progressions according to common practice principles is an important concern and one that is often elusive for the first- or second-year theory or ear-training student. For example, one would want the student to harmonize the first five bass notes of the major scale as I-V -I6-IV-V, I-vii6-i6-IV-V, or I-V

-I6-IV-V, I-vii6-i6-IV-V, or I-V -I6-ii6-V rather than I-ii-iii-IV-V or the non-diatonic succession of major chords, I-II-III-IV-V, as occurs in Jim Croce's "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown." The chorus of Stevie Wonder's "As" features the progression i-V

-I6-ii6-V rather than I-ii-iii-IV-V or the non-diatonic succession of major chords, I-II-III-IV-V, as occurs in Jim Croce's "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown." The chorus of Stevie Wonder's "As" features the progression i-V -i6-IV; the chorus of Irene Cara's "Flashdance" features I-V

-i6-IV; the chorus of Irene Cara's "Flashdance" features I-V -I6-IV-V11-V. (The V11-V succession in rock music is analogous to the cadential I

-I6-IV-V11-V. (The V11-V succession in rock music is analogous to the cadential I -V of Classical music.) Augmented sixth chords which resolve to V and I

-V of Classical music.) Augmented sixth chords which resolve to V and I are found in several Beach Boys' songs. Secondary dominants are frequently found in the music of Prince, They Might Be Giants, Beatles, Elvis Costello, R.E.M., Neil Young, The Pixies, The Traveling Wilburys, Bob Dylan, and others. Chord successions such as I6-IV, V6-I, V

are found in several Beach Boys' songs. Secondary dominants are frequently found in the music of Prince, They Might Be Giants, Beatles, Elvis Costello, R.E.M., Neil Young, The Pixies, The Traveling Wilburys, Bob Dylan, and others. Chord successions such as I6-IV, V6-I, V -I6, and V

-I6, and V /V-V6 are extremely common, as well.

/V-V6 are extremely common, as well.

A strong dissension between Classical and rock music, however, occurs in the area of modulation. Modulation in rock and popular music is seldom discussed in theory and more rarely in ear training classes. Modulation to the key of the dominant (or the key of the relative Major when the original key is minor), the mainstream practice of Classical period music, is mostly nonexistent in rock music. The most common (and uninteresting) modulation in rock music is that from the tonic key to the key of the flatted supertonic, a well-worn cliche which usually occurs at the beginning of the last verse. There are many other less frequently used modulations which can provide good harmonic perception exercises. To list a few:

Beach Boys, "Don't Worry Baby"—modulations between each verse and chorus—verses in the key of I Major and choruses in the key of II Major:

verse: Key of C: I-IV-V-I-IV-V-ii-V-iii

V/ii (V/ii = D:V)chorus: Key of D: I-ii-V-I-ii-V-IV11 (IV11 = C: V11)

Christopher Cross, "Think of Laura"—verses: I Major, choruses: VI Major:

verse: Key of C: I-V6-ii-vi-IV

I-V6-ii-vi-IV-V-V/ii (V/ii = A:I)chorus: Key of A: I-vi-V/ii-ii-V--I-vi-V/ii-ii-V

Van Halen, "Jump"—verses and choruses: I Major, bridge:  Major:

Major:

verse: Key of C: I bridge: Key of :

vi-IV-V-I-vi-IV-V-I-vi-IV-V-I

Jefferson Starship, "No Way Out"—verses: i minor, chorus:  Major:

Major:

verse: Key of d minor: i iv-V-i-VI-V-iv-VI-V

i-iv-V-i-VI-V-iv-VI-ivchorus: Key of Major:

I-V -I6-IV

I-V-I6-IV

Talking Heads, "And She Was"—verses: I Major and  Major, chorus: I Major, bridge: v minor:

Major, chorus: I Major, bridge: v minor:

verses: Key of E:

Key of F:I-IV-I-IV-I

I-IV-I-IV-I

IV-I-V-I-IV-V-I-IV-I-V-I-IV-V/V-Vchorus: Key of E: I-IV- -IV-I-IV-

-IV-I

bridge: Key of b minor: i-VI-i-VI

Talking Heads, "Wild Wild Life"—verses:

verses: Key of F:

Key of:

I-V-IV-I-I-V-IV-I

I-IV-V-I-IV-V-V/ii (V/ii =: I)

chorus: Key of :

I-IV-V-IV-I-I-IV-V-IV-I

I-IV-V-IV-I-IV-V-IV-V (V = F: I)bridge: Key of :

VII-I-IV-V-IV-VII-I-IV- -I (I = F:

)

Chicago, "You're the Inspiration"—intro: VI Major, verse: I Major, chorus: III Major:

intro: Key of A: I-IV-V-I-IV-V (V = C: III) verse: Key of C: I-I6-iii-vi-vi -IV

I-I6-iii-vi-vi-IV

transition: V6-I-IV6- -V6/vi-vi-V6/V-V-V6/vi-VI (VI = E: IV) V6

chorus: Key of E: I-I6-IV-V-I-I6-IV-V- (

= C: V)

IV-V

Traditional ear training courses seldom include "metric" dictation, yet in rock music, such a study is appropriate. Rock groups often explore meters other than 4/4. The following is a brief list of unusual meters:

| Allman Brothers | Whipping Post | (verse: 6/8) (chorus: 11/8 = 6/8 +5/8) |

| Band | Just Another Whistle Stop | (verse: 4/4) (chorus: 7/4) |

| Beach Boys | Hold On Dear Brother | (verse: 3/4) (chorus: 5/4 = 3+2) |

| Beatles | All You Need Is Love | (verse: 7 = 4+3) (chorus: 26 = 4+4+4+4+4+4+2) |

| Good Morning Good Morning | (intro: 4+4+4+4) (verse: 5+5+5+3+4; 5+4+3+3+4+4 .....) |

|

| She Said She Said | (verse: 10 measures of 4/4) (chorus: 4+4+3+3+3; 3+3+3; 3+3+3) |

|

| Adrian Belew | Laughing Man | 11 |

| Byrds | Get to You | (verse: 5/8) (chorus: 6/8) |

| Tribal Gathering | 5 | |

| Cream | Passing The Time | (intro: 5+5+5; 2+2+3; 2+2+3; 5+5+5; 2+2+3; 2+2+3) (verse: 4+4+4+4; 4+3+4+3) |

| King Crimson | Indiscipline | 5 |

| Thela Hun Ginjeet | 7/16 vs. 4/4 |

| (numerous compositions involving polymeter—"Three Of A Perfect Pair," "Frame By Frame," "Discipline," "Neal And Jack And Me," and others) | |

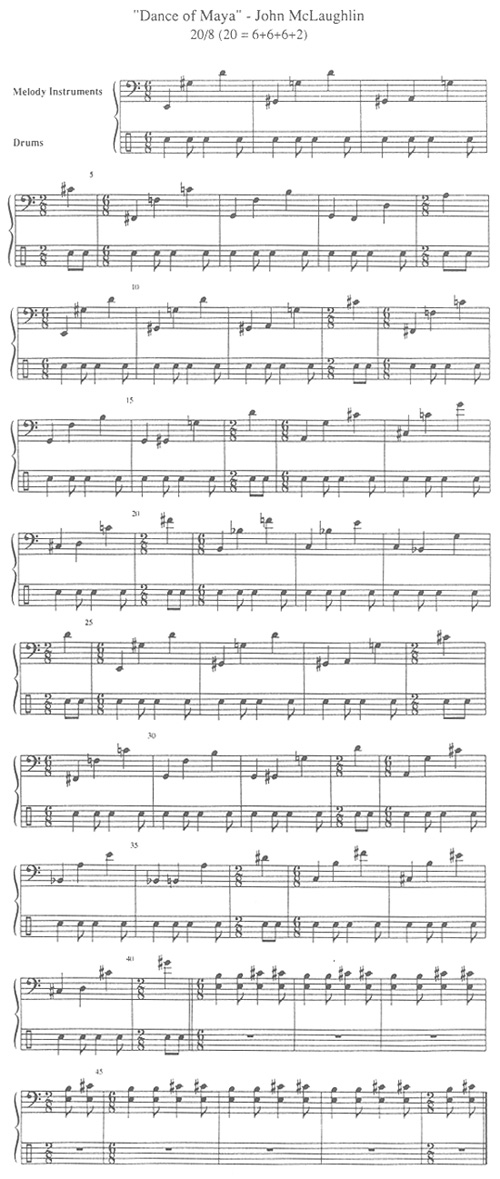

| John McLaughlin | Dance of Maya | 20/8 |

| Dawn | (20 = 6+6+6+2) |

Example 1.

| Police | Mother | 7 |

| Synchronicity I | 6 |

| Murder By Number (drums introduction: quarter-note triplets which sound like 3/4. The band enters in 4/4 while the quarter triplets continue in the drums.) | |

| Sting | Straight to My Heart | 7 |

| Weather Report | Hernandu | (verse: 17 = 6+6+5) (solos: 11 = 6+5) |

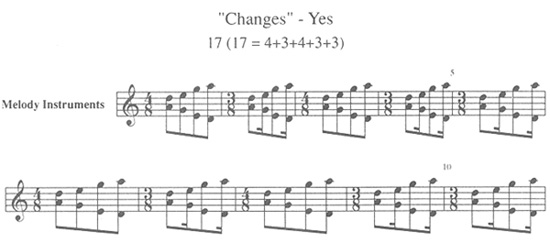

| Yes | Changes | (17 = 4+3+4+3+3) |

Example 2.

| Frank Zappa | Pound For A Brown On The Bus | 14/16 (14 = 3+4+3+4) |

| Little House I Used To Live In | 11 | |

| Marqueson's Chicken | (series of 7s, followed by series of 5s, then 6s) |

|

| Tink Walks Amok | 11 | |

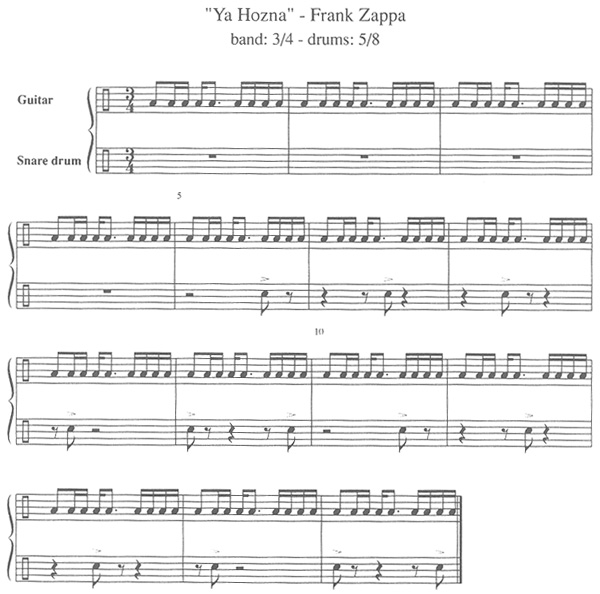

| Ya Hozna | (band: 3/4, drums: 5/8) |

Example 3.

Rock music and recordings of non-Classical music should be studied in the teaching of ear training and theory. Rock music's parallels with Classical music reinforce those theoretical constructs underlying both styles—the differences between the two also lead to a better general understanding. The student who listens only to common practice period music in the classroom or at the computer, devoid of context and instrumentation, will not be prepared to understand musical styles either aurally or intellectually.