An Analytical Approach to Seventeenth-Century Music: Exploring Inganni in Fantasia Seconda (1608) by Girolamo Frescobaldi1

With the passing of the fourth centennial of Girolamo Frescobaldi's birth (1983), a number of commemorative meetings and festivals attempted to solidify research concerning this composer known for his extensive use of chromaticism, which was considered revolutionary for the seventeenth century.2 The current state of Frescobaldi research includes the publication of his complete works, a biographical outline of his life, and the recreation of the "sound-world" of Frescobaldi's time.3 However, few attempts have been made to develop an appropriate analytical approach generated through an understanding of seventeenth-century musical thought that would reveal general theoretical principles concerning compositional devices. Scholars note individual phenomena frequently found in the works of Frescobaldi; however, a detailed study of these concepts and an endeavor to combine them into an analytical approach still is lacking.

The aim of this essay is to illustrate an analytical approach for seventeenth-century contrapuntal music that was developed through an examination of elements (particularly inganno) noted by scholars as common in the music of Frescobaldi.4 The resulting data collected through a computer-assisted analysis reveals subject generation, thematic unity, as well as other elements which contribute to form and structure in Fantasia Seconda (1608) by Frescobaldi.

Inganno: Definition and History

Inganno (It., deception) is a technique of hexachordal transposition in which solmization syllables of hexachords (ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la) are assigned to notes of a melody, thus resulting in transformed or altered (deceptive) thematic material.5 This procedure of melodic reshaping was employed particularly in imitative compositions in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries by replacing tones in one hexachord with tones from another hexachord carrying the same syllable. Frequently, the pattern of hexachordal syllables is established by a melodic passage, often the subject or answer, which is introduced and later manipulated to produce (deceptive) imitative thematic material. The relationship between this altered or transformed (deceptive) restatement of the melodic figure and the original melodic passage is retained through their hexachordal syllable patterns.6 The analytical approach for this study is based on the theory of hexachords that was commonly used by Frescobaldi and other seventeenth-century composers.7 The assigned solmization syllables act as a unifying factor between the subject, answer, and other thematic material. Inganno, when examined through a hexachordal analysis, suggests an association between melodic segments that would otherwise appear rhythmically and melodically distorted and unrelated.

The first printed appearances of the term inganno (pl., inganni) were in 1603 by the theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi and the composer Trabaci.8 Artusi's discussion, definition, and illustration of inganno, found in the second part of his L'Artusi, was used to "discriminate between the right and wrong use [according to Artusi] of such features as Suppositi [It., substituted tones], Fiori [It., flowers], Fioretti [It., little flowers, perhaps grace notes], Inganni, Accenti [It., accents, perhaps ornamental figures], Artificcii [It., devices], bemoaning the ways in which the 'Moderni Confonditori' misuse them."9 Artusi's discussion would suggest that inganno was employed by composers at this time as well as before 1603.

When it comes to inganni, music still has its inganni - not the customary inganni, but according to the usage of the new masters. Skilled composers of the past and some modern ones (I refer only to the good ones) have ably shown the way in which to make use of them; but they are misunderstood by most others. Therefore, I should like to demonstrate the [conventional] way in which skillful composers have made use of inganni in their melodic lines (cantilene). An inganno occurs whenever one part enters with a theme (soggietto) and the next follows not with the same [pattern of] intervals but with the same [sequence of solmization] syllables. This explanation should be made clear by the following example:

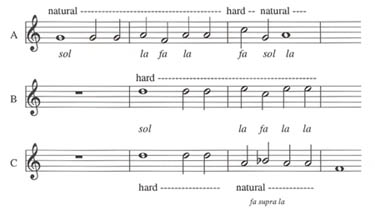

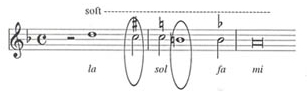

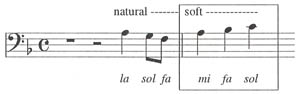

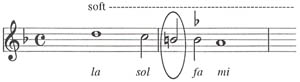

Example 1. Inganno as defined by Artusi (1603)

One expects an answering part [b] to repeat or transpose the same intervals as the leading voice [a], and so one is somewhat deceived to find that it answers with the same syllables but not the same melodic shape [c]. It is possible to make use of the device as both an inganno and as the subject of a double fugue (doppia fuga).10

Artusi establishes a correct model, at least in his own eyes, for the use of inganni. He implies that different (incorrect) variations of inganni were employed by other composers possibly for subject generation beyond his suggested double fugue.

Trabaci, unlike Artusi, did not give a definition of inganno when he first used the term but provided descriptive names and some musical examples illustrating three possible kinds of inganni: (1) those that "modulate" from one hexachord to another (similar to Artusi's illustration); (2) those that substitute one note that has been borrowed from some other hexachord; and (3) those that contain more than one such modulation or note substitution.11

The study of inganno is rooted in the theory of hexachords. An exploration of inganni in Fantasia Seconda by Frescobaldi (1608) reveals subject generation and provides a link between segments of thematic material when hexachordal syllable strings are used to represent these melodic themes. The analysis of the fantasy begins by examining the types of hexachords found in the subject. This is determined by adding solmization to the notes of the subject.

Adding Solmization Syllables to Subject and Answer Material

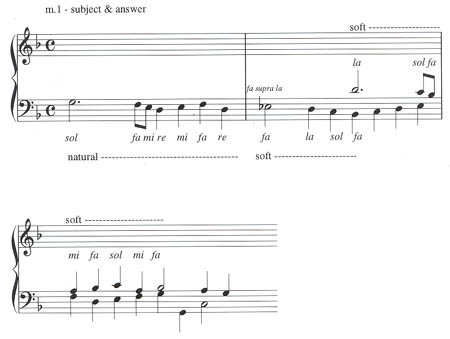

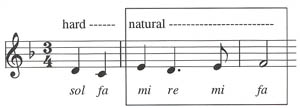

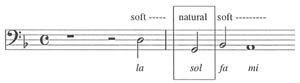

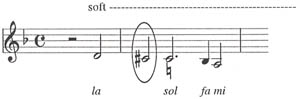

Each hexachord is unique due to the placement of the half-step marked by the syllables mi-fa. Therefore, the key to determining solmization syllables for subjects and answers is the location of the half-step. In the subject of the second keyboard fantasy, a half-step occurs between the second and third notes (F-E). This semi-tone is marked by fa-mi of the natural hexachord as illustrated in Example 2. The eighth tone of the subject (a half note,  ) is marked by the syllable fa as simply a flatted tone or as an example of fa supra la where the note exceeding the six-degree syllables of a hexachord by a second is assigned the syllable fa without mutation.12 The final portion of the subject is found in the soft hexachord because the

) is marked by the syllable fa as simply a flatted tone or as an example of fa supra la where the note exceeding the six-degree syllables of a hexachord by a second is assigned the syllable fa without mutation.12 The final portion of the subject is found in the soft hexachord because the  requires the syllable fa. Therefore, the subject begins in the natural hexachord and switches by mutation to the soft hexachord.

requires the syllable fa. Therefore, the subject begins in the natural hexachord and switches by mutation to the soft hexachord.

Following the assigning of syllables to the subject, the answer is treated in a similar manner. Because the half-steps in the answer are located between  and A, the entire answer is found in the soft hexachord as illustrated in Example 2.

and A, the entire answer is found in the soft hexachord as illustrated in Example 2.

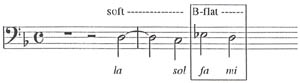

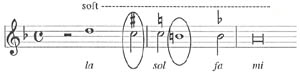

Example 2. Subject and Answer of Fantasia Seconda

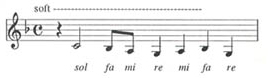

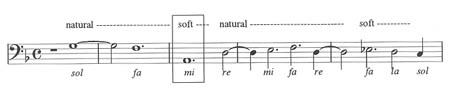

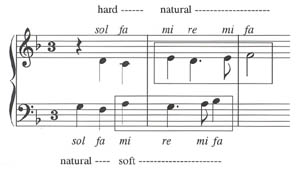

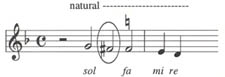

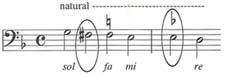

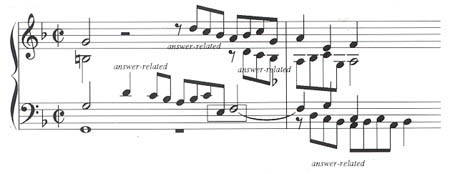

Because the sequence of syllables for the subject (sol - fa - mi - re - mi - fa - re - fa - la - sol - fa), and the answer (la - sol - fa - mi - fa - sol - mi - fa) are different, thematic material throughout the composition may be linked specifically to the subject or the answer by its hexachordal solmization. Example 3 contains three musical illustrations that are associated with the subject and the answer by means of their hexachordal syllables.

Example 3. Subject-related and Answer-related material

Measure 10—Subject transposed to soft hexachord.

Measure 9—Answer transformed through inganni.

Measure 88—Answer altered by chromatic additions which create a complete (full) chromatic fourth.

The subject material in measure ten is simply a transposition of the original, using the soft hexachord instead of the natural. An example of inganno (switching to the natural hexachord) appears in measure nine with answer-related material. Chromatic additions (notes inserted to fill in melodic intervals by half-steps) are found with answer-related material in measure eighty-eight.

Computer-Assisted Analysis

The computer assists in this analysis by providing hexachordal identification of subject-related and answer-related material quickly and accurately.13 The computer identifies in which hexachord a given note can receive a specific syllable. In other words, "g" is sol in what hexachord? In this case, the answer is natural. The computer looks for a match between a note and a syllable, and if it finds one, it then supplies the hexachord in which the match occurs. To speed the process, all of the syllables of the subject are checked against a melodic theme, usually six to eight notes in length. The computer returns a list of hexachords as shown in Table 1. When the subject (G, F, E, D, E, F, D,  , D, C,

, D, C,  ) is checked with these hexachordal syllables (sol - fa - mi - re - mi - fa - re - fa - la - sol - fa), the computer returns the hexachord list: natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - soft - soft - soft - soft. As subject material is examined throughout the composition, the match is also found in measures one, five, ten, seventeen, fifty-five, and sixty-five. Once hexachordal identification is achieved by the computer for the entire composition (including all subject and answer material), a table of hexachord lists is provided for the user to interpret (see Table 1). The hexachords in this table have been abbreviated (i.e., nat = natural hexachord, bfl = B-flat hexachord, dnat = D-natural hexachord).14 Some measure numbers are followed by a letter (e.g., 10-s) indicating a particular voice in a measure (e.g., measure 10, soprano voice). This technique is only employed when there are multiple occurrences of subject-related and/or answer-related material in a single measure.

) is checked with these hexachordal syllables (sol - fa - mi - re - mi - fa - re - fa - la - sol - fa), the computer returns the hexachord list: natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - natural - soft - soft - soft - soft. As subject material is examined throughout the composition, the match is also found in measures one, five, ten, seventeen, fifty-five, and sixty-five. Once hexachordal identification is achieved by the computer for the entire composition (including all subject and answer material), a table of hexachord lists is provided for the user to interpret (see Table 1). The hexachords in this table have been abbreviated (i.e., nat = natural hexachord, bfl = B-flat hexachord, dnat = D-natural hexachord).14 Some measure numbers are followed by a letter (e.g., 10-s) indicating a particular voice in a measure (e.g., measure 10, soprano voice). This technique is only employed when there are multiple occurrences of subject-related and/or answer-related material in a single measure.

Table 1. Computer-Assisted Analysis of Fantasia Seconda—Interpreted

Subject: G F E D E F D E-flat D C B-flat Syllables: sol - fa - mi - re - mi - fa - re - fa - la - sol - fa

section 1:

section 2:

section 3:

section 4,5:

section 6,7:Hexachords:

nat nat nat nat nat nat nat soft soft soft soft

nat nat nat nat nat nat

(soft soft soft soft soft soft soft)

nat nat nat nat nat nat nat soft

nat nat [soft] nat nat nat nat soft soft

(soft soft soft soft)

nat nat nat nat nat nat nat

(soft soft soft soft soft soft [hard])

nat nat nat nat nat nat nat [hard]

nat nat nat nat

(soft soft soft [nat])

nat nat [soft soft soft soft]

(hard hard [nat nat nat nat])

at nat [soft soft]

(soft soft [bfl bfl bfl bfl])

(soft soft [bfl hard])

(soft soft soft soft [dnat dnat])

nat [soft soft] nat

(soft soft soft soft soft soft [bfl])

(soft soft soft soft soft soft)

nat nat nat nat nat nat nat [soft]

nat nat nat nat [soft soft soft]

(soft soft soft soft soft soft soft soft nat)

(soft soft soft soft soft soft [hard dnat])

nat nat nat nat [soft hard]

nat nat nat nat (*chromatic fourth)

nat nat [soft soft soft soft]

nat nat nat nat nat nat [soft]

nat nat [soft soft soft soft soft]measures:

1, 5, 10-s, 17, 55-a, 65-b+

6-t, 60-t, 65-a, 74-a

10-a, 16+, 52-s, 53-b, 59-t, 74-s

13

18+

20, 22-a~, 28

21, 24-a, 29-s, 51-a, 56, 63, 85**

22-s

25-t

25-s~, 26-b~, 54-t~

27-b

32-b, 33

32-a

34, 37-s, 47

38

39

44

46

53-t, 55-s

52-t

55-b

59-b

60-b

61

72~

76**~+, 79**~+, 87***~+

78, 84*

80

81+

Answer: D C B-flat A B-flat C A B-flat Syllables: la - sol - fa - mi - fa - sol - mi - fa

section 1:

section 2:

section 3:

section 4,5:

section 6:

section 7:Hexachords:

soft soft soft soft soft soft soft soft

soft soft soft soft soft soft

soft soft soft soft soft soft [nat nat]

(nat nat nat nat nat nat [bfl])

soft soft soft soft soft soft soft

(nat nat nat nat nat [soft])

(nat nat nat [soft soft soft])

soft soft soft soft

soft soft [bfl bfl bfl bfl]

(nat nat [soft soft])

soft soft [bfl bfl hard]

soft soft soft soft soft soft [nat nat]

(nat nat nat nat)

soft soft soft soft [dnat bfl]

soft soft soft soft soft [dnat]

(nat nat nat nat nat nat)

(nat nat nat nat nat [hard])

soft soft soft

soft [nat] soft soft

soft soft soft soft (*Chromatic fourth)

soft soft [bfl bfl]

(nat nat [soft soft soft soft])

(nat nat [soft bfl])

soft soft [nat] soft

(nat nat nat [soft])measures:

2, 6-s, 8, 12, 14, 15-a, 23, 25- b, 30, 51, 54-s, 57-a, 57-s, 60-a+, 62-s+

4, 19-s, 24-s, 27-b, 29-t, 29-b, 50-s, 50-a, 54-t

9

15-b

18

19-t

21

26-s, 58-s, 62-b, 71, 72-s

37-b

43

45

50-t

57-b

58-a, 70-t, 70-b

70-s

72-a, 88-t

73

77*, 81*

76~+, 79~+, 83-s~+

80**~+, 88-s***~+, 90-a**~+

83-a~+, 84~+

86

88-b~+

89~+

90-bnat = natural hexachord, bfl = B-flat hexachord, dnat = D-natural hexachord

10-s = measure 10, soprano voicebrackets [ ] indicate inganni, parentheses ( ) mark transpositions of the original subject or answer, asterisks (*) highlight measures containing chromatic passages or chromatic additions, plus signs (+) indicate augmentation of subject-related or answer-related material, multiple asterisks (**) signify an incomplete chromatic fourth or a complete chromatic fourth (***), the tilde symbol (~) marks fragmented subject-related or answer-related material.

To the casual observer, Table 1 may appear rather overwhelming. However, each hexachord list represents an occurrence of subject-related or answer-related material closely associated with the original subject or answer by syllable patterns, yet frequently transformed through inganno, transposition, and/or chromatic additions. The user interprets the raw data so that these specific elements (inganni, transpositions, chromatic additions) can be categorized and studied for the entire composition. The hexachord lists in Table 1 have been interpreted and are signified in the following manner: brackets [ ] indicate inganni, parentheses ( ) mark transpositions of the original subject or answer, and asterisks (*) highlight measures containing chromatic passages or chromatic additions. Other abbreviations employed throughout the table include a plus sign (+) indicating augmentation of subject-related or answer-related material; multiple asterisks (**) signifying an incomplete chromatic fourth15 or a complete chromatic fourth (***);16 and the tilde symbol (~) marking fragmented subject-related or answer-related material.

Note that the primary hexachords throughout the composition (including inganno and transposition) are the natural and soft, reflecting the subject and answer. The technique of switching hexachords in inganno generally follows the rule for mutation in that the soft hexachord is not found interlocked with the hard hexachord.17 The natural hexachord is used when switching and interlocking the soft and hard hexachords. It is also evident that the syllable-string of the subject and answer can support a variety of pitch successions and contours affecting the melodic (as well as the tonal and modal) structure inhabiting that string.

Thematic Unification

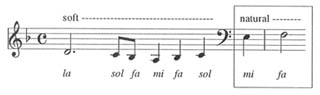

The thematic unification that is revealed in Table 1 is examined more carefully in the remaining examples (Exs. 4-6) to demonstrate different types of alterations and manipulations used by Frescobaldi on subject-related and answer-related material. Inganni, transpositions, chromatic additions, and measure numbers are indicated for each illustration. Throughout these examples, it is also interesting to compare the rhythmic differences between these various segments of subject-related and answer-related material. Not only are their pitches different, but distinctive rhythmic changes are also created through augmentation (often creating an impression of ostinato or cantus firmus) and diminution.18 Even though rhythmic inganni are not suggested by Artusi or Trabaci, it appears that Frescobaldi was not satisfied with mere melodic transformation. The clearest pattern of rhythmic change (as subtle as it may be) can be identified in the newly generated thematic material to be discussed momentarily.

Types of Inganni

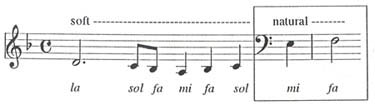

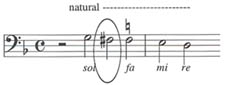

Frescobaldi employs two main types of inganni throughout Fantasia Seconda to alter and generate thematic material (see Example 4). Type #1, which occurs most often, contains a modulation to another hexachord (similar to Trabaci's first type).19 In most of these instances of inganni, hexachordal switching moves from natural to soft or soft to natural hexachords (the primary hexachords in the original subject and answer). Squares are employed to mark inganni in this example.

Example 4. Inganno Types (Subject-Related)

Inganno Type #1: Measure 32—Modulate to another hexachord (similar to Trabaci's first type).

Inganno Type #1: Measure 33—Modulate to another hexachord with transposition (similar to Artusi's example).

Inganno Type #2: Measure 18—Single note substitution (similar to Trabaci's second type).

Example 4. Inganno Types (Answer-Related)

Inganno Type #1: Measure 9—Modulate to another hexachord (similar to Trabaci's first type).

Inganno Type #1: Measure 21—Modulate to another hexachord with transposition (similar to Artusi's example).

Inganno Type #2: Measure 79—Single note substitution (similar to Trabaci's second type). Also found in measures 76, 83, 89.

Another example of inganno, similar to the first type, involves transposition of the opening material (similar to Artusi's example). Several examples of this type of inganno may be viewed in two ways. First, as illustrated in the second part of Example 4, this subject-related and answer-related material can be seen as a modulation to another hexachord with transposition. In other words, measure thirty-three begins in the hard hexachord (a transposition) and then modulates to the natural hexachord (inganno) instead of continuing in the hard hexachord. Second, the melodic segment may be viewed beginning with inganno and then returning to the original hexachord. For example, a second interpretation of measure thirty-three begins with inganno (modulation or switch to the hard hexachord) and returns to the original hexachord of the subject (natural). For this illustration, this author employs the first interpretation (following Artusi's model) because the return to the original hexachord (using the second method) is not as aurally convincing as the modulation with transposition.

The second and final type of inganno, which occurs in measures eighteen and seventy-nine, involves a single note substitution in both subject and answer material. This example of inganno is similar to Trabaci's second type. None of the examples of inganni found in Fantasia Seconda follows Trabaci's third type (those that contain more than one modulation or note substitution).

Other Methods of Subject Generation

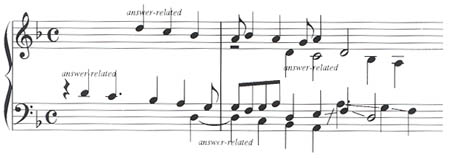

After Frescobaldi creates new subject and answer material through inganni, he presents these transformed melodic figures imitatively at the beginning of several sections of the composition. Inganno is but one type of melodic reshaping employed by Frescobaldi to generate subject material that is presented as the basis for a specific section of the composition. Further subject generation is created by chromatic additions (chromatic pitches added to the subject or answer which fill in the melodic intervals of the subject or answer by half-steps). In Example 5, each melodic theme represents a subject of a section that sounds like a new subject not related to the original subject. However, each is based on the same syllable pattern as the original subject, yet it is transformed through inganno or chromatic additions as well as distinctive rhythmic patterns developed through augmentation and diminution. These rhythmic distortions add to the unrelated nature of the material. The most common rhythmic features include diminution to primarily eighths (m. 50), quarters (m. 32), and augmentation to longer note values (mm. 76, 84, 88). Again the inganni and chromatic additions are marked by squares and circles, respectively, in Example 5.

Example 5. Subject Generation (Subject-related)

Measure 32—New subject for new section (3) generated through inganni (type #1).

Measure 76—New subject for new section (7) formed through chromatic addition creating an incomplete chromatic fourth.

Example 5. Subject Generation (Answer-related)

Measure 50—New answer of new section (4) generated through inganni (type #1).

Measure 84—New answer of new section (7) generated through inganni (type #1).

Measure 88—New answer generated by chromatic additions which create a complete (full) chromatic fourth.

The chromatic additions, introduced in Example 5, are examined more carefully in Example 6.

Example 6. Chromatic Additions (Subject-related)

Measure 79—Subject material transformed through chromatic addition creating an incomplete chromatic fourth.

Measure 87—Complete chromatic fourth is created through chromatic additions.

Example 6. Chromatic Additions (Answer-related)

Measure 80—Answer transformed through chromatic addition which creates an incomplete chromatic fourth.

Measure 90—Answer transformed through chromatic addition which creates an incomplete chromatic fourth.

Frescobaldi also attaches chromatic additions (or alterations) to thematic material creating chromatic fourths (a melodic pattern which fills in the interval of a fourth with chromatic half-steps).20 Similar to the subject and answer material brought about through inganno, chromatic additions generate thematic material that does not sound closely related to the original subject or answer. However, thematic unity and association is discovered when hexachordal syllables are taken into account. Complete chromatic fourths appear in measures eighty-seven and eighty-eight (see Example 5).

All of the chromatic fourths illustrated in Example 6 are descending (following the contour of the subject and the answer), something noted as a common phenomenon by several scholars including Frederick Hammond and James Ladewig.21 Each of the chromatic fourths occurs with subject and answer material in its original hexachord (i.e., without transposition) yet are rhythmically altered (from the original subject or answer) through augmentation.

Form and Structure

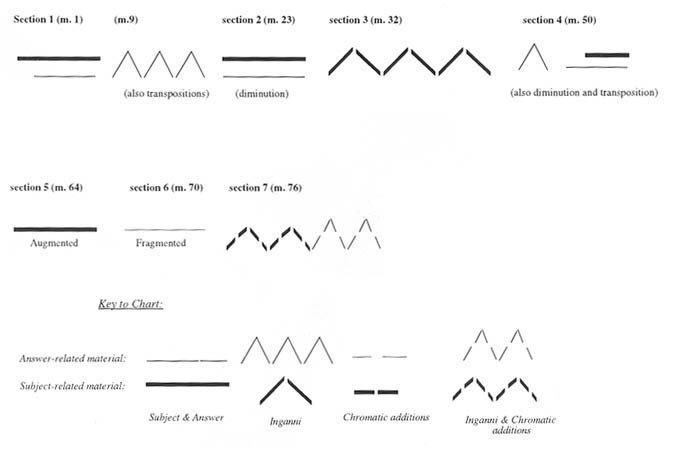

Now that the association between melodic and thematic segments has been examined, questions regarding their effect on form and structure can be considered. Each of the previous examples (Ex. 4-6) contains important elements (inganni, transpositions, and chromatic additions) contributing to a formal structure as indicated in Example 7 (see also Appendixes 1 and 2). The sections of this fantasia exhibit features used as the basis for a particular portion of the work giving it distinction from others. These areas of the composition are separated by cadences22 and meter changes and are characterized by specific features (inganni, transpositions, fragmentation, chromatic additions, augmentation and diminution). As the composition progresses, the interrelations of the thematic material grow more complex and increase in frequency.

Example 7. Elements Contributing to Form and Sectional Uniqueness

Measure 23—Section 2 featuring subject and answer with original pitches and only rhythmic alterations.

Measure 32—Section 3 featuring subject-related material transformed through inganni (type #1).

Measure 50—Section 4 featuring answer-related material transformed through inganni and diminution.

Measure 64—Section 5 featuring subject-related material transformed through augmentation.

Measure 70—Section 6 featuring answer-related material that is rhythmically altered.

Measure 76—Section 7 featuring thematic material transformed through inganni, augmentation, fragmentation, and chromatic additions.

Section one begins with the introduction of the subject and the answer (see Example 2). The thematic material is altered, beginning in measure nine (see also Example 3), through transposition and inganno. The original form of the subject and answer returns in section two (see Example 7). Therefore, when the elements of sections one and two are combined, an arch-like structure (subject - inganni/transpositions - subject) becomes apparent. In sections three and four, a new subject (for section three) and answer (for section four) are generated through inganno (see Examples 5 and 7). Section five returns to a statement of the original subject in augmentation, while the final two sections contain several alterations of the original subject and answer. Only one occurrence of the original subject or answer (slightly fragmented) arises in either of these two sections. Section seven is the most chromatic part of the composition. Frescobaldi's chromatic genius is most evident during this portion of the composition, as he includes all four elements of the previous sections (inganni, augmentation, fragmentation, and chromatic additions) to develop the subject and answer material to the fullest extent. Through the extensive manipulation and alteration of thematic material in section seven, Frescobaldi brings this composition to its climax, journeying far from the original subject and answer.

In summary, subject alteration and generation involves such phenomena as inganno (employed to create transformed and deceptive thematic material), chromatic additions (chromatic tones used to fill in whole steps leading to the formation of the popular chromatic fourth), transposition, fragmentation, diminution, and augmentation. Several examples of this process have been noted in Frescobaldi's Fantasia Seconda (1608) as illustrated in Examples 3-7. A careful examination of the elements reveals thematic unity and sectional uniqueness all contributing to form (see Example 7 and Appendixes 1 and 2). Through this analysis Frescobaldi's organizational schemes as well as thematic development become apparent, further identifying the creativity of this composer. Perhaps these elements influenced other composers as they subsequently developed contrapuntal compositional styles in the eighteenth and later centuries.23

The exploration of inganno and the use of hexachordal syllables as a basis for an analytical technique may provide a technical link to composers of the past and supply a mechanism for tracing influence to later composers (even so far as chromatic and thematic variations and other possible distortions similar to techniques employed by twentieth-century composers). Inganno has also been suggested to support and refute the addition of accidentals when compositions might be considered more tonal than modal.24 Beyond the scope of this study, the computer-assisted analysis may allow for cataloging inganno types as well as melodic and rhythmic varieties possibly suggesting a compositional style which would aid in the link and authenticity of works by various seventeenth-century composers.

The recent research into the music of Frescobaldi supports the need for continued investigation into the compositional devices generated by this composer, furthering knowledge and understanding of a pivotal period of music—the seventeenth century. Perhaps we have not fully explored the music of this period because compositional elements are not clearly discernible; rather, they are buried in the style of the composer, making it extremely difficult to classify and examine.

Appendix 1. Elements Contributing to Form: Inganni, Chromatic Additions,

Transpositions, Augmentation and Diminution

Section 1:

m. 1 - Subject and answer are introduced.

Balance between the number of subject and answer entrances.

mm. 9, 18, 21 - Inganno occurs with the subject and the answer.

mm. 10, 15, 16, 20, 22 - Transpositions of the subject and answer occur.

Section 2:

m. 23 - Subject and answer returns (rhythm altered), no inganno, one transposition.

Section 3:

m. 32 - Subject of this section (which sounds like a new subject not related to the

original subject) is based on the same syllable pattern as the original subject,

yet it is altered through inganno.

Few occurrences of the answer.

All subject material is based on this newly generated subject of this section.

Section 4:

m. 50 - Answer (subject material) of this section is based on the same string of syllables

as the original answer, yet it is transformed through inganno and diminution.

Many transpositions of the subject occur. Inganno appears twice.

Section 5:

m. 64 - Augmented and original subject. No occurrence of the answer.

Section 6:

m. 70 - Answer-dominated section; however, answer is altered (rhythmically).

There is a fragmented relationship between the answer material in this section

and the original answer. Few occurrences of the subject.

Section 7:

m. 76 - Subject and answer altered by inganno, augmentation, fragmentation, and

chromatic additions which create the chromatic fourth. Inganno occurs most often

in this section.

Appendix 2. Structural Chart

Fantasia Seconda by Frescobaldi

1A shorter version of this article was presented during the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Kansas City, October 1992.

2The proceedings for the two international meetings, the first in Madison, Wisconsin and the second in Ferrara, are collected in two works: Frescobaldi Studies edited by Alexander Silbiger (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), and Girolamo Frescobaldi nel IV centenario della nascita: atti del convegno internationale di studi (Ferrara, 9-14 settembre 1983) edited by S. Durante and D. Fabris (Florence: Olschki, 1986).

3Frederick Hammond, Girolamo Frescobaldi—A Guide to Research (New York: Garland, 1988), 176-179.

4Scholars have noted the use of inganno by various composers: Gesualdo, see Roland Jackson, "On Frescobaldi's Chromaticism and Its Background," The Musical Quarterly 57 (1971): 263, 265; Trabaci, see John Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 105 (1978-1979): 3, and Roland Jackson, "The Inganni and the Keyboard Music of Trabaci," Journal of the American Musicological Society 21 (1968): 204-8; Wert, see Anthony Newcomb, "Form and Fantasy in Wert's Instrumental Polyphony," Studi musicali 7 (1978): 87-90; Willaert, see Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," 10; Claudin, see Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," 5; and Macque, see Anthony Newcomb, "Frescobaldi's Toccatas and Their Stylistic Ancestry," Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 111 (1984-1985): 39, and Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," 1, as well as others suggested by Harper in his New Grove article (see note 5).

5John Harper, "Inganno," in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillian, 1980), 227.

6The primary hexachords referred to here are the natural hexachord (C, D, E, F, G, A), soft hexachord (F, G, A,  , C, D), and the hard hexachord (G, A, B, C, D, E). For a detailed discussion of hexachords see Gaston G. Allaire, The Theory of Hexachords, Solmization and the Modal System, Musicological Studies and Documents 24 (Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1972).

, C, D), and the hard hexachord (G, A, B, C, D, E). For a detailed discussion of hexachords see Gaston G. Allaire, The Theory of Hexachords, Solmization and the Modal System, Musicological Studies and Documents 24 (Rome: American Institute of Musicology, 1972).

7As suggested by Jackson, "The Inganni and the Keyboard Music of Trabaci," 205; the technique may seem obscure to us. However, it was quite normal to the musicians of that time because they learned this craft as they studied hexachords.

8Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," 3.

9Ibid.

10Ibid.

11Roland Jackson, "The Inganni and the Keyboard Music of Trabaci," 205-6.

12Allaire, The Theory of Hexachords, Solmization and the Modal System, 45.

13Prolog used for programming was developed by Advanced A. I. System's Prolog, Version M-2.06, P.O. Box 39-0360, Mountain View, California 94039.

14The B-flat and D-natural hexachords (transposed soft and hard, respectively) are added to the aforementioned hexachords (natural, soft, hard) to allow for accidentals that imply transposition to these hexachords.

15Jackson notes the importance of the chromatic fourth when describing a chromatic genus as suggested by Cerreto and Vicentino. See Jackson, "On Frescobaldi's Chromaticism and Its Background," 260.

16The terms, "incomplete" and "complete", (Harper uses the term "full" instead of "complete") are employed to differentiate between chromatic fourths that contain some half-steps (e.g., C,  , D, E, F; thus incomplete) and those that are completely filled in by semi-tones (e.g., C,

, D, E, F; thus incomplete) and those that are completely filled in by semi-tones (e.g., C,  , D,

, D,  , E, F).

, E, F).

17Allaire, The Theory of Hexachords, Solmization and the Modal System, 47.

18This was also noted by Frederick Hammond, Girolamo Frescobaldi (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1983), 129.

19Jackson, "The Inganni and the Keyboard Music of Trabaci," 206.

20James Ladewig, "The Origins of Frescobaldi's Variation Canzonas Reappraised," Frescobaldi Studies, ed. Alexander Silbiger (Durham: Duke University Press, 1987), 238-239; and Jackson, "On Frescobaldi's Chromaticism and Its Background," 260.

21Frederick Hammond, Girolamo Frescobaldi, 131; and James Ladewig, "Luzzaschi as Frescobaldi's Teacher: A Little-Known Ricercare," Studi Musicali 10 (1981): 241-264.

22A further discussion of cadences, including hierarchy and type, may be found in Ladewig, "Luzzaschi as Frescobaldi's Teacher: A Little-Known Ricercare," 254-55; Newcomb, "Frescobaldi's Toccatas and Their Stylistic Ancestry," 28-44; and in Chapters Two and Four of the author's dissertation, "Toward a Theory of the Music of Girolamo Frescobaldi Developed Through Computer-Assisted Analysis of Selected Works" (Ph. D. diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1991), 57-63, 109-13.

23Robert Morris made the following observation at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Kansas City, October 1992: If a descending melodic line (E-D-C, mi-re-ut in the natural hexachord) was altered through inganno (substituting re of the soft hexachord), the result would be the functional line, E-G-C (mi-natural, re-soft, ut-natural).

24Harper, "Frescobaldi's Early Inganni and Their Background," 7-8.