The question of value in popular music has probably crossed the mind of every music scholar in America—our scholarly commitment almost always depends in some way on music's aesthetic qualities, and we encounter its popular forms daily. Answers to the question are often not pursued at length, whether because the pursuer lacks sufficient interest or the answers prove to be too complex, but the potential rewards merit serious attention. Even though popular music's vast appeal and financial resources can easily lead its composers to imitate current trends more vigorously than they strive for original contributions, it remains likely that the most talented among them have produced eminently valuable musical works of art.

In order to determine how good popular music can be, though, we need to consider how it can be good. What features of a popular song might exhibit value—the ways in which the song is engaging, intriguing, or attractive—and how might these features relate to one another? How can our examination of these features enable us, as Anthony Newcomb has described the task of criticism, "to make the best possible argument" for a popular song? 1 One way to set the stage for such an inquiry is to consider how features are customarily examined in the critical analysis of the traditional art music canon.

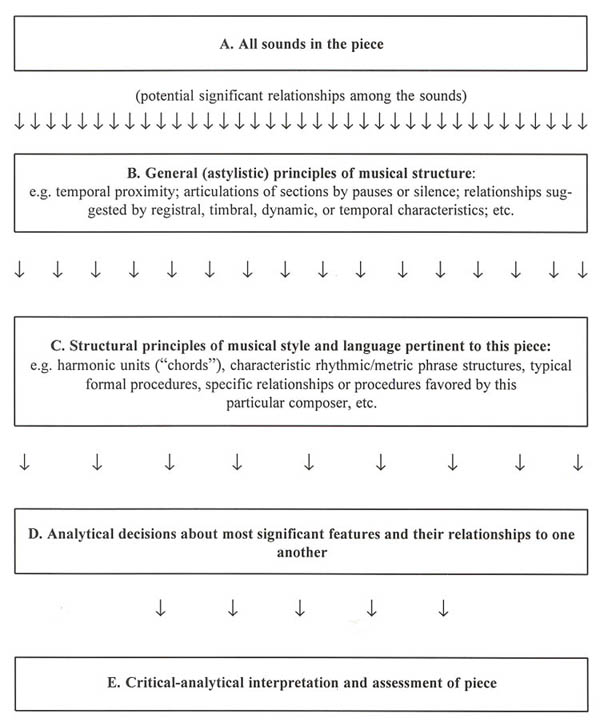

In general, this analytical practice has emphasized internal syntactical issues, focusing on the ways that the listener interprets relationships among various events within a piece. The analyst desires to demonstrate, with progressive precision and insight, which relationships most merit the listener's attention. All the sounds in a piece (shown at A in Figure 1) imply as many potentially significant relationships as there are possible combinations among the sounds.

Figure 1. Analytical model for listeners' process of selecting significant syntactical relationships within a piece.

However, the listener automatically filters most of these relationships out of consideration, first (at B) through general principles of musical grouping and structure. Favored relationships might, for example, be perceived among temporally proximate sounds as they constitute larger groupings, registrally and/or timbrally similar sounds as they convey a melody, or sounds that share an articulation or a metrical/rhythmic characteristic so as to form a textural strand.

These principles do not depend on any particular style, although a given principle may only apply in some styles. The listener's knowledge of pertinent musical style and language, however, provides a basis for further gross filtering of relationships (at C). For example, a knowledge of typical metrical structure might influence the perception of temporal grouping, and an understanding of harmonic function could clarify the relationship between the two phrases of a typical half-cadence/authentic-cadence period.

These general filtering processes are "analytical" in that they explain how music works by identifying parts of the whole and the ways in which the parts relate to one another. The scope of their conclusions varies according to the accessibility of the piece and the complexity of applicable stylistic principles; in any event, though, an analyst usually acknowledges the conclusions tacitly rather than stating them explicitly. However, they form a context within which the analyst can make decisions (at D) about which specific and/or unique features and relationships are most significant, and how they are significant. In turn, these decisions are used (at E) as the basis for analytical conclusions.

In practice, the process goes back and forth, as possibilities are discovered and tested. Conclusions at one stage can override provisional conclusions at an earlier stage about a given piece; a tonal return, observed at C, might relate events that were not related by the temporal groupings of B, or the discovery of a motivic connection at D might lead to a structural conclusion at E that qualifies or negates general assumptions about sectional relationships in B and C. Conclusions can also, over the course of time, revise the principles upon which B and C are based, as observations about how we hear this piece corroborate, refine, or qualify generally held notions of how we hear other pieces like it, or music in general. The analyst's primary goal, however, is to arrive at interpretive conclusions about the relationships among elements within the individual piece.

Analytical interest in facts about an individual piece other than the musical events within it depends on the analyst, on the specific piece, and on the nature of the information. Even when these facts are considered, however, they are usually judged to provide a context for the relationships among musical elements—they themselves are viewed as neutral premises, rather than as contributors to the value of the piece.

For example, one typical subject of analysis might be a nineteenth-century art song; in this case, one such fact would be the original text. In most cases, a listener would consider the quality of the text essential to the value of a song, and, indeed, a sensitive analyst can incorporate the interpretation and assessment of the text into his analysis of the song as a whole. But such an approach is exceptional. Much more often, the text is considered as a compositional premise, rather than the focus of the analysis (the music): the analyst asks, "Given this text, what did the composer accomplish in his or her musical setting?" Sometimes the music is seen to revise the text by projecting or enhancing particular features, but even in this case value seems most evident in the interesting way in which the music does this, rather than within the "new" text itself.2 This musical emphasis probably results from the inherently musical interest and aptitude of the analyst and the analyst's audience, as well as the fact that in most nineteenth-century art songs the text is a premise, having been established as an independent entity before the song was written, rather than being written by the composer as part of this specific act of creation.

Other facts about an art song are assigned even less analytical significance. Instrumental choices, for example, seem incidental (especially when a standard arrangement, such as voice accompanied by solo piano, is chosen); at most, the instruments selected suggest possibilities or impose limits. The original performers of a piece seem similarly irrelevant to analysis, except in unusual cases in which a particular performer's capabilities or limitations have significant implications for compositional choices. Even when these factors are considered, though, they almost always remain value-neutral premises—it is not the choice of instruments or performers that seems aesthetically significant, but rather the compositional decisions that the composer has made in the context of these choices.

It has been possible in recent decades for American composers of popular music to realize tremendous monetary profit and prestige as fruits of their labor. In this respect, they have had as much incentive as any other composers to compose for expedience—to aim at sales figures and popularity rather than enduring aesthetic achievement. Given this situation, it should not surprise us if many popular songs, like many compositions from other eras, fare poorly by most measures of aesthetic value. Where significant aesthetic value does exist in a popular song, though, it may not be revealed by investigating the internal musical relationships that are emphasized in Figure 1; in these terms, the song may seem hopelessly repetitive and simple. But we need to cast our aesthetic net more widely, for the text, instrumentation, and original performers in a popular song may well be more significant than is customarily acknowledged in the case of art song.

The text of most popular songs in recent decades, for example, is in most cases written either by the composer or in close collaboration with the composer. Therefore, it often needs to be considered an essential part of the song's creation, rather than a neutral or static premise.3 Furthermore, when the most authoritative and common version of a composition will be a recording, the composer can choose specific instruments and performers without regard to their availability for future performances. These choices, too, should be considered in analysis as potentially significant elements of the composition.

The main portion of this essay will examine Paul Simon's song "Graceland," showing how observations about text, instrumentation, and performers might be integrated with those about musical processes into a unified analytical interpretation.4 First, though, one additional observation is necessary. Just as musical processes are interpreted in the context of stylistic norms that are established outside the piece itself, so also a knowledge of applicable circumstances should inform the interpretation of nonmusical elements. Indeed, Newcomb and others, including Edward Cone, Joseph Kerman, Lawrence Kramer, Gary Tomlinson, Leo Treitler, and Martin Williams, have suggested that the listener's potential perception of a musical work can be most fully illuminated by considering relevant cultural/historical information, context within a later work, the influence of contemporaneous art, literature, etc., and, where applicable, information about the composer's life, other compositions, and personal perceptions of the piece.5 Such an approach seems particularly important when analyzing music that is as explicitly bound up with its culture as popular music can be.

In order, then, to "make the best argument" for a popular song, Figure 1 can be revised as shown in Figure 2, considering text (A2) and instrumental and performer choices (A3) as essential attributes of the work of art, and filtering all these elements through principles of poetic structure (B2) as well as our knowledge of various circumstantial facts (C2).

Figure 2. Broader model for identifying critical significance.

One might even further divide the poetic principles into astylistic and stylistic categories, if such a degree of discrimination seems warranted in a particular case. When this variety of features is explored for a given song, it is likely that some features will emerge as fundamental premises upon which an analytical interpretation can be constructed. In the case of "Graceland," for example, the text presents a central conceit; it follows here:6

[Verse 1, Section b (voice tacet in Section a)]:

The Mississippi Delta was shining

Like a National guitar

I am following the river

Down the highway

Through the cradle of the civil war

[Chorus 1]:

I'm going to Graceland

Graceland

In Memphis Tennessee

I'm going to Graceland

Poorboys and Pilgrims with families

And we are going to Graceland

My traveling companion is nine years old

He is the child of my first marriage

But I've reason to believe

We both will be received

In Graceland

[Verse 2, Section a]:

She comes back to tell me she's gone

As if I didn't know that

As if I didn't know my own bed

As if I'd never noticed

The way she brushed her hair from her forehead

[Verse 2, Section b]:

And she said losing love

Is like a window in your heart

Everybody sees you're blown apart

Everybody sees the wind blow

[Chorus 2]:

I'm going to Graceland

Memphis Tennessee

I'm going to Graceland

Poorboys and Pilgrims with families

And we are going to Graceland

And my traveling companions

Are ghosts and empty sockets

I'm looking at ghosts and empties

But I've reason to believe

We all will be received

In Graceland

[Verse 3, Section a]:

There is a girl in New York City

Who calls herself the human trampoline

And sometimes when I'm falling, flying

Or tumbling in turmoil I say

Oh, so this is what she means

She means we're bouncing into Graceland

[Verse 3, Section b]:

And I see losing love

Is like a window in your heart

Everybody sees you're blown apart

Everybody feels the wind blow

[Chorus 3]:

[Oooh,] In Graceland, in Graceland

I'm going to Graceland

For reasons I cannot explain

There's some part of me wants to see

Graceland

And I may be obliged to defend

Every love, every ending

Or maybe there's no obligations now

Maybe I've a reason to believe

We all will be received

In Graceland

[Coda]:

[Oh Graceland, Graceland, Graceland

I'm going to Graceland]

Somewhat elliptically (and thus similarly to many recent Simon songs), this text explores several overlapping themes: the narrator's relationships to his culture, to other people, and to God. The opening references to various American cultural entities reflect the location of his journey: a National steel-bodied guitar (evoking delta blues), the Civil War, and Elvis Presley's mansion, Graceland. By the end of the first chorus, though, the experience is personalized: a sense of seeking is conveyed by "Poorboys and Pilgrims," the broken relationships suggested by the word "but" after "first marriage," and the hope of redemption at this particular place, as underscored by the literal meanings of "Grace" and "land."

The dual focus on personal and general perspectives continues throughout the song, as the second verse recounts a past experience of the narrator's and concludes by graphically describing his pain or incompleteness, while at the same time generalizing it by saying what happens, not what happened to him. Again, in the second chorus, while the narrator says that "we"—all the Poorboys and Pilgrims with families—are going to Graceland, the ghosts and skeletons of his own past have become more evident to him than his physically present son.

The personal anecdote in the third verse suggests that, in general, our helplessness in life's turmoils underscores the passive way in which we receive the redemption of "Graceland." In the final chorus, the narrator continues to examine his destiny as he wrestles with general principles of accountability, hoping that redemption is universally available.

The text reveals important elements through its thematic content and its formal features.7 Here, both of these means project a pervasive sense of fluidity, of continuing progress from one thing to the next. Thematically, this idea is introduced by the opening image of the river, sustained by the continuing physical journey described throughout the song, and implicitly perpetuated by the narrator's uncertainty in the last chorus. It is reinforced and enriched by his seamless mental passage among various images, perspectives, issues, and points in time.

While this passage is mainly conveyed through the sequence in which ideas are presented within the narrative form, it is also reinforced by some references that cut across the form. These include obvious parallelisms, such as that between the two women and that between the narrator's live and dead traveling companions, and occasional double meanings, such as "Graceland," mentioned above, and the implication that an uncapitalized "civil war" (as printed in the liner notes) might refer to personal relational strife. These elements reinforce an associative aspect of fluidity that is first signalled by the title of the piece, which sets a tone for association by being a title of something other than the song itself, and a multiply iconic one at that. The song is obviously not intended to be Finnegans Wake (shared river-beginnings notwithstanding!), but association is established as a significant element.

Within the poetic form, the verse chorus structure exhibits fluidity as the functions of verse and chorus blur into one another. The chorus continually evolves, rather than remaining the same or nearly so on each appearance. Conversely, the verses become somewhat chorus-like, as the last four lines of the third verse are essentially the same as those of the second. The appearance of the Graceland idea (originally belonging to the chorus) in the last verse adds a final flourish to this functional blurring.

Several aspects of the text, then, support the notion of fluidity—reference is made to images that are somehow fluid, ideas progress and refer to one another fluidly, terms have fluid meanings, and the functions of formal components flow into one another. Thus two aspects of fluidity, continuity and change, are highlighted. Just as an object in a river is inexorably borne along, progressing measurably but seemingly endlessly, so the narrator's physical journey continues. So, too, does his mental pilgrimage, winding inward from external cultural awareness to the engagement of personal concerns, yet without final resolution. At the same time, the object may be locally tossed about, flipping over, temporarily submerging, or delaying in an eddy; the text is correspondingly changeable in its formal manipulations, changes of scene and perspective, and cross-references.

All of these textual features provide a conceptual foundation upon which other elements of the song can build. They do so, first, with internal musical relationships, and, second, with associations evoked by referential compositional choices. Many of the syntactical relationships in the music display fluidity by blurring the norms of symmetry and repetition that are associated with popular-song style. For example, the regular eight-measure harmonic progression that accompanies each verse section, two measures each of E (I), A (IV),  (vi), and B (V), is preceded by two measures of vamping on E. While these two measures also provide a textual arrival point at the end of Sections 2a and 3a, their repeated figure always provides a static preparation as well, and flows seamlessly into the section that follows. Also, the final chorus does not end, but flows into a coda, and, while the repeat-until-fade of the concluding instrumental chorus riff is not unusual, it, too, reinforces the textual lack of resolution.

(vi), and B (V), is preceded by two measures of vamping on E. While these two measures also provide a textual arrival point at the end of Sections 2a and 3a, their repeated figure always provides a static preparation as well, and flows seamlessly into the section that follows. Also, the final chorus does not end, but flows into a coda, and, while the repeat-until-fade of the concluding instrumental chorus riff is not unusual, it, too, reinforces the textual lack of resolution.

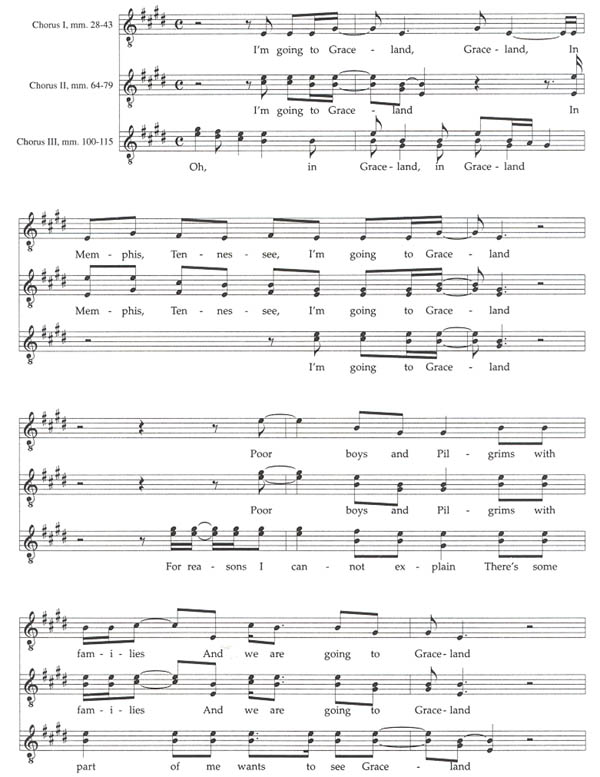

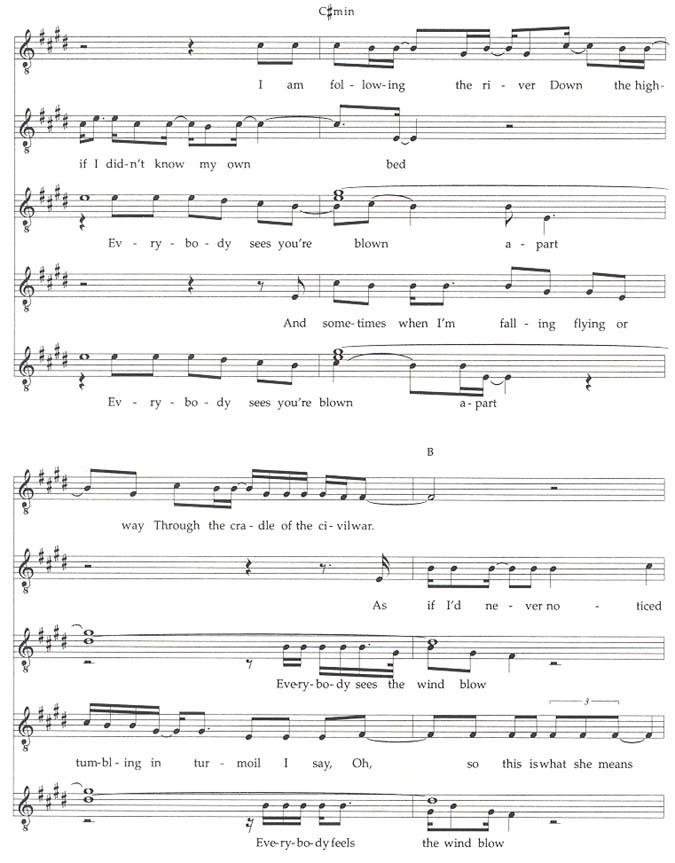

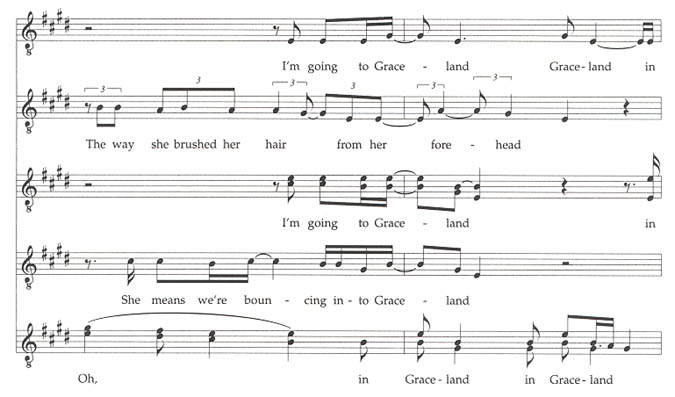

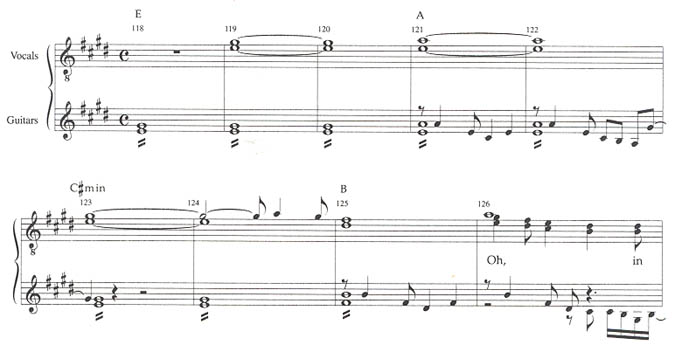

Melodic variation reinforces the textual flexibility. As the text varies in successive appearances of the chorus, not only are voices added, but Simon varies his own melody in each appearance (see Example 1).

Example 1. Vocals in Choruses. (Simon's lead vocals always in lowest voice)

The musical treatment of the verses is more remarkable: the listener expects the text to change in successive verses, but doesn't have reason to expect the striking amount of melodic flexibility that Simon adds as well.

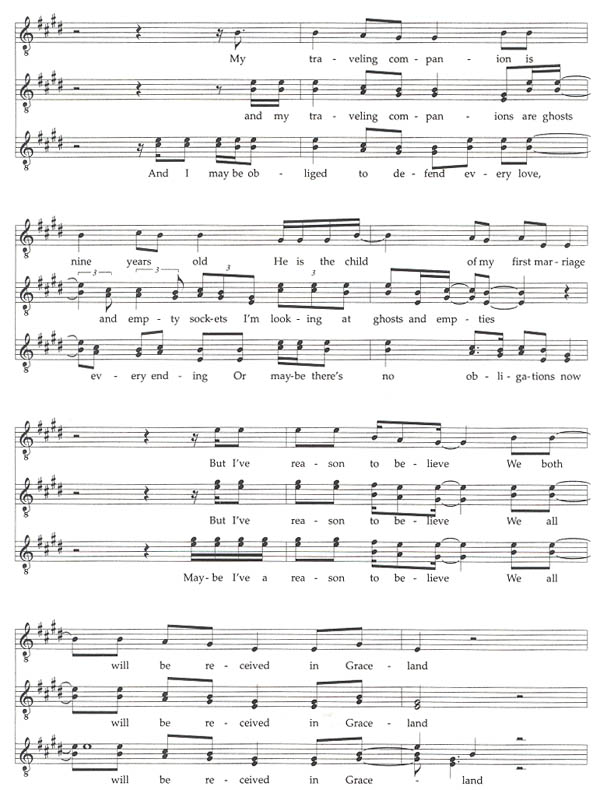

This is shown in Example 2, which aligns the vocal lines in each section for comparison.

Example 2. Vocals in Verse Sections. (Simon's lead vocals always in lowest voice)

Verses 2 and 3 each contain two text sections; Section a in each exposes information, while Section b draws a conclusion about that information. The parallel texts in Sections 2b and 3b clearly share a melodic outline, with slight rhythmic variations.

The first verse only includes text in its b section, and its expository nature associates it with the a sections of the other verses. Its melody and that of Section 3a are closely related, following the same pitch outline until they diverge toward the ends of their sections to lead to a chorus and a b section, respectively. The melody in Section 3a is an interesting and natural variation on that in Section 1b, but the real interest occurs in Section 2a.

Here Simon paces the melody differently in response to the textual content, which results in an entirely different line. Where 1b and 3a conversationally ramble for two measures from a strongly established  down to E, 2a haltingly reveals "her" departure, mostly within a major third, and stops dead upon reaching the word "gone" at the end of the first full measure. Then, where 1b and 3a rest on tonic at the harmonic arrival on A, 2a blurts out the narrator's reaction in the high register. Where the pace of the next phrases in 1b and 3a is similar to that of their first phrases, 2a rests again; in its last phrase the narrator becomes a bit more resigned, and the line relaxes and conforms to the pacing of 3a as both lead into b sections. These adjustments in melodic pacing, then, reflect the fluid variations in textual perspective. Finally, when the textual reference to Graceland makes its way into the third verse at the end of 3b, the melody reinforces its appearance with the

down to E, 2a haltingly reveals "her" departure, mostly within a major third, and stops dead upon reaching the word "gone" at the end of the first full measure. Then, where 1b and 3a rest on tonic at the harmonic arrival on A, 2a blurts out the narrator's reaction in the high register. Where the pace of the next phrases in 1b and 3a is similar to that of their first phrases, 2a rests again; in its last phrase the narrator becomes a bit more resigned, and the line relaxes and conforms to the pacing of 3a as both lead into b sections. These adjustments in melodic pacing, then, reflect the fluid variations in textual perspective. Finally, when the textual reference to Graceland makes its way into the third verse at the end of 3b, the melody reinforces its appearance with the  -E motive that is associated with the word in the chorus.

-E motive that is associated with the word in the chorus.

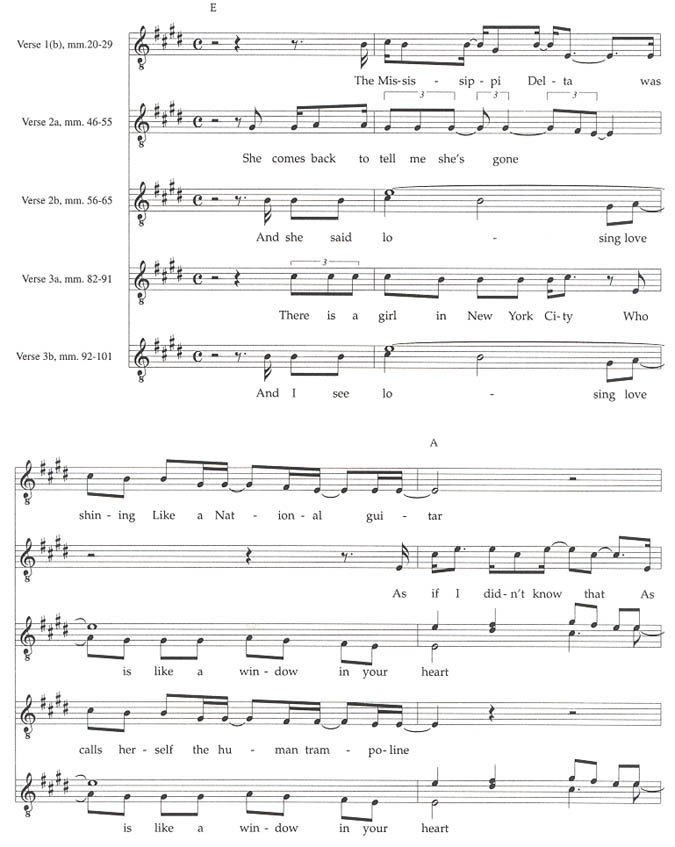

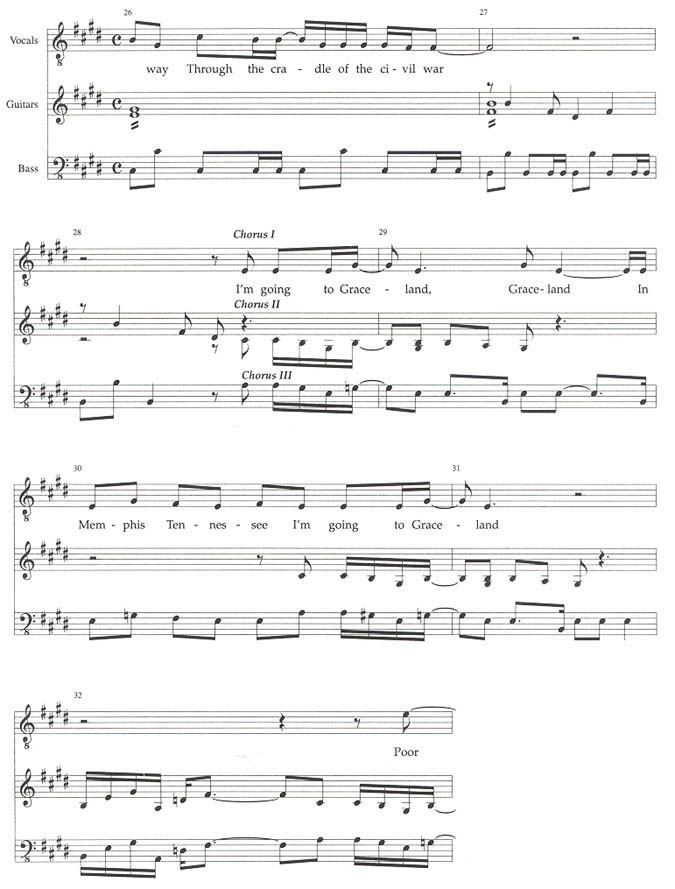

Fluidity is also manifested through the way that the lead vocal relates to the other parts. The background vocals enter, not at a formal articulation, but toward the end of the second verse with their text-painting of the wind, thus providing a smooth transition into the more standard joining-in in the second chorus. While Simon's free treatment of the beat (durations in Example 2 approximately represent this) contrasts sharply with the even pulse of the bass (Example 3a) in the verses, this distinction is blurred as the two flow together somewhat, along with the guitar, at several points in the chorus, with a less even rhythm (see Example 3b, mm. 28-31 and 3c, m. 38).

Example 3. Rhythm Throughout Verses.

3a. Bass Rhythm Throughout Verses

3b. Beginning of First Chorus

3c. Middle of First Chorus

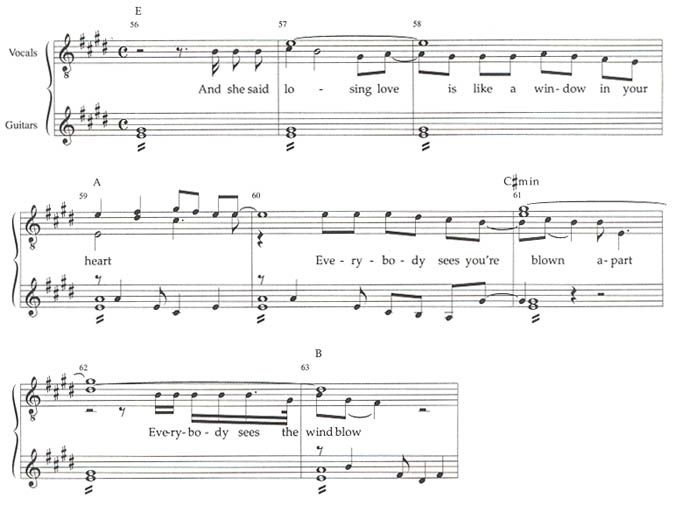

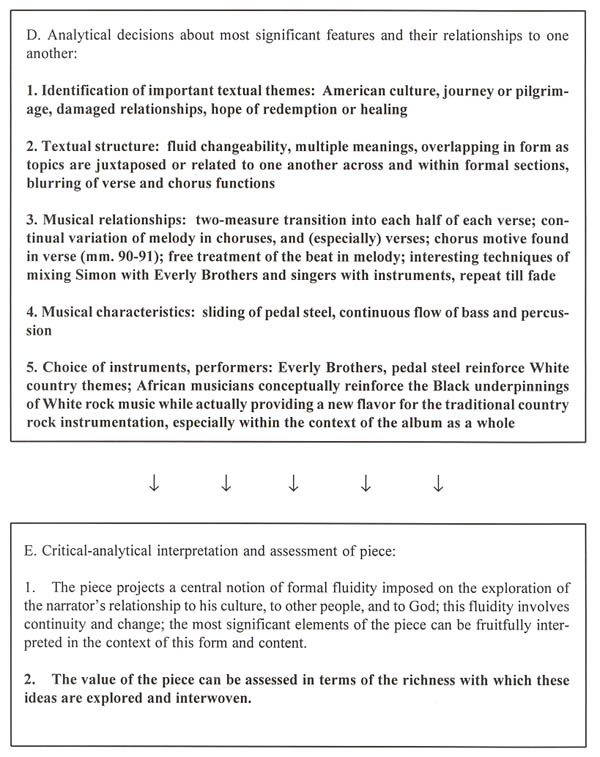

This unity supports the chorus's idea of acceptance, redemption, and being received. (The related idea of falling helplessly may be connected to the only detail of harmonic syntax that seems significant, as the IV-vi progression in the verses frustrates purposive movement by retrogressing in terms of classical norms.) The background vocals, too, float in and out of the instruments' notes—after flirting with the guitar lines at the end of the second and third verses (Example 4a, mm. 56-63; cf. mm. 92-99), they merge into them for several measures at the harmonically corresponding point at the beginning of the coda (Example 4b, mm. 118-26).

Example 4. Background Vocals and Guitar.

4a. End of Verse 2 (background vocals and guitar are the same at end of Verse 3)

Example 4b. Beginning of Coda

In these cases a sense of fluidity is exhibited by the way in which significant musical events relate to one another. It is also established by the overall effects projected in the individual lines. Simon's free treatment of the beat in the verses projects rhythmic fluidity, and the vocal lines also tend to flow by avoiding  and its associated tension (Simon only sings four, eighth-note,

and its associated tension (Simon only sings four, eighth-note,  's, in mm. 60, 96, 100, and 126; the background vocals use a few more, three of which, in mm. 63, 99, and 125, do contribute to dominant tension). The sliding of the pedal steel guitar produces fluid glissando lines (which connect with the text's National steel-bodied guitar, very often played with a bottleneck), and the bass and percussion flow steadily through the verses, only occasionally (in the case of the percussion instruments) introducing a small elaboration.

's, in mm. 60, 96, 100, and 126; the background vocals use a few more, three of which, in mm. 63, 99, and 125, do contribute to dominant tension). The sliding of the pedal steel guitar produces fluid glissando lines (which connect with the text's National steel-bodied guitar, very often played with a bottleneck), and the bass and percussion flow steadily through the verses, only occasionally (in the case of the percussion instruments) introducing a small elaboration.

In addition to making possible particular sounds and musical relationships, Simon's selection of instruments and performers evokes a fluid network of associations that connects with the meaning of the text and the premise of the album as a whole. The text of this song refers to Simon's own American cultural roots, musical and otherwise, and his inclusion of the Everly Brothers and the pedal steel guitar supports the White, country flavor of the lyrics. (C. O'Brien has discussed the relationships between the guitars in "Graceland" and in the recordings of Elvis, noting on the one hand that the guitar here quotes a lick from Elvis's "Mystery Train," while at the same time the pedal steel was never particularly associated with him, but seems to evoke more of a "pre-Elvis white American South.")8

At the same time, all the instrumentalists on the song are Black Africans, thus exemplifying a theme that dominates the album, Simon's conscious use of various African materials in his own artistic pursuits. The undertaking is expressed in the lyrics of another song on the album, called "Under African Skies"—"take this child, Lord/From Tucson Arizona/Give her the wings to fly through harmony . . . This is the story of how we begin to remember . . . These are the roots of rhythm and the roots of rhythm remain."

Other things being equal, a listener might be inclined to assess each of these various implications of instruments and performers as simply, binarily, related or not related to the central conceit of the song. But in this case, the listener is encouraged to think in more fluid terms, interpreting the various levels of relationships as part of an ebb and flow of association. This is because the degree of African influence on this song is located within a continuous range of varying degrees of influence on the other songs on the album. "Homeless," for example, is a fully integrated collaboration between Simon and the South African a cappella group Ladysmith Black Mambazo. At the other extreme, "That was Your Mother" and "All Around the World, or The Myth of Fingerprints," each connect with South Africa only by using American bands (the Zydeco band Good Rockin' Dopsie And The Twisters and the East Los Angeles band Los Lobos, respectively) that use saxophone and accordion, which Simon associated with some of the South African bands that he had heard. In "Graceland" the African influence runs slightly below the surface, and is thus analogous to the Black influence on Elvis: in "Graceland" the musicians' contribution resides in the unique flavors that their playing adds to the song, while the Black influence on Elvis was often profoundly audible, but not usually explicitly demonstrated by the presence of Black musicians.

Simon's technique of using specific instrumental and performer choices to support central ideas of the song is, in fact, typical of his personal compositional style. Various analogous combinations of musical style and cultural flavor have been applied throughout his career. In the Simon and Garfunkel days, these included the many uses of Art Garfunkel's striking voice, and more isolated instances such as "El Condor Pasa" with Los Incas. Most recently, the technique informs the whole of the Brazilian-influenced Rhythm of the Saints album, but even his earliest solo albums similarly treated a host of individual songs. Representative examples among the first three albums alone include, on Paul Simon: Los Incas again ("Duncan"), Stefan Grossman's bottleneck guitar ("Paranoia Blues") and Charlie McCoy's bass harmonica ("Papa Hobo"); on There Goes Rhymin' Simon: the Dixie Hummingbirds ("Loves Me Like a Rock") and the Onward Brass Band ("Take Me to the Mardi Gras"); and on various cuts of Still Crazy After All These Years: the Chicago Community Choir, Phoebe Snow, The Jessy Dixon Singers, Toots Thielemans' harmonica, and Sivuca's accordion.

This technique interacts interestingly with various features of "Graceland." The text and music establish the importance of fluid association, which suggests that the associative aspect of instrumental and performer choices might be significant. In turn, the associations suggested by these choices invite the listener to perceive a varied range of musical and cultural experiences as being significantly related to the piece, thus enriching the aesthetic experience that it embodies. At the same time, these associations support Simon's extramusical, textual points, both within the song (his projection of "Graceland" as a familiar refuge, presumably one with whose cultural elements the narrator identifies) and within the album (his tribute to his musical "roots").

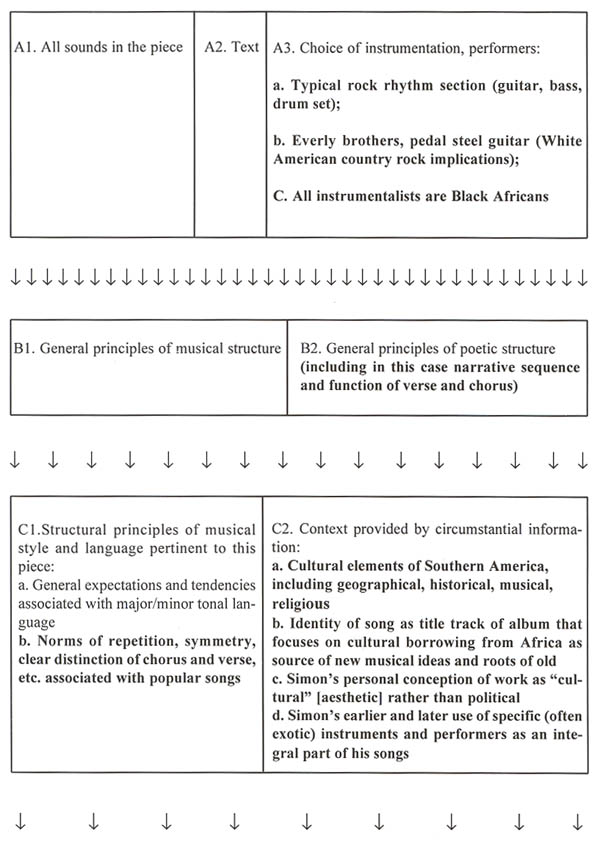

Figure 3 places all of these observations about "Graceland" within the scheme of Figure 2.

Figure 3. Observations about "Graceland."

The objectively perceived elements of the piece—musical sounds, text, and instrumental and performer choices—are shown at A1, A2, and A3. These are filtered through the various kinds of information that provide contexts for their interpretation at B and C; appropriate information for "Graceland" is shown here at C1 and C2. The intersection of elements and background information yields the various decisions shown at D.

Finally, at E, we can list conclusions that result from the observations made at D. We might state that a sense of fluidity is effected by and affects the various elements of the piece, and that this fluidity shapes textual considerations of cultural, interpersonal, and spiritual relationships, as exemplified in the narrator's contemplation of his situation and in Simon's invocation of his musical influences. This conclusion then forms a basis for evaluating the piece, as a listener observes the degree of richness and subtlety with which various elements support, elaborate upon, or complement this central idea.

Several different elements, then, can inform the critical analysis of a popular song. Some of these elements will form fundamental premises, while others embellish upon or support these premises. The nature and proportions of these relationships would vary from piece to piece, and these variations could form the basis of some fundamental categorical distinctions among popular songs. Many might be considered text-driven, in that the meaning of the text forms the basis for interpretation; others might derive their fundamental impulse from music-syntactical relationships or from their identity as exemplary instances of particular musical styles.

In any event, though, it seems clear that any attempt to evaluate a popular song in aesthetic terms would have to consider a wide range of factors, as this study has done. The relevance of a factor to critical analysis depends on its general applicability to listeners' aesthetic experiences of the piece, and perhaps on the clarity with which it can be related to other factors. If these criteria are fulfilled, the investigation of such a factor is profitable in critical music analysis.

To be sure, investigations that do not conform to these criteria may be quite useful and interesting for other purposes, such as strictly poetic analysis, or logical or political evaluation of the text, or assessment of the work's sociopolitical implications. In the present case, for example, while the narrator's perspective on grace was not evaluated on theological grounds, because such an evaluation did not seem to bear on the listener's aesthetic experience of the piece, such an investigation might conceivably be undertaken.

More attractive to many critics in the case of this particular album have been sociopolitical questions. For example, Louise Meintjes has focused on the "political discourse" in the album rather than the "musical discourse"; she associates a focus on the musical discourse (especially on the part of White South Africans) with an adherence "to a bourgeois aesthetic principle which privileges the inherent transcendency of art," and further points out that Simon's own emphasis on his "cultural" (by which he seems to mean aesthetic or artistic, as opposed to political) point of view tends to align him with this kind of perspective.9 Consistent with her stated purpose, Meintjes's comments on the music itself are restricted to a general acknowledgment of its skill and craft, and to observations about the social implications of general stylistic techniques.10

In Meintjes's terms, my study addresses a bourgeois interest in aesthetic value. The appropriateness of this perspective for interpreting the song on its own terms is supported by Simon's own "cultural" inclination, as reflected both in the statements Meintjes quotes and in the nature of his work as a whole. I am not judging one kind of investigation as better than the other, but rather defining purposes so as to clarify the relationships among various studies.

It seems clear that if some popular songs are considered appropriate subjects for critical analysis, this process should combine the investigation of internal syntactical features with an inquiry into other issues. I have shown how this might be done in the analysis of "Graceland." At the same time, the pursuit of critical analysis requires that the analytical focus be limited to issues that help to elucidate the listener's aesthetic experience. Such a middle course between a narrow focus on internal musical matters on the one hand, and a proliferation of observations that are tangential to aesthetic issues on the other, should provide an effective route to the interpretation and evaluation of each piece on its own terms.

An earlier version of this essay was read to the 1991 national meeting of the College Music Society in Chicago. I am grateful to Baylor University for support during a summer sabbatical, part of which was used to pursue this research, and also to the students in my Advanced Analysis class in the spring of 1992 for their assistance in refining my analytical conclusions regarding "Graceland."

1Anthony Newcomb, "Schumann and Late Eighteenth-Century Narrative Strategies," 19th Century Music 11 (1987): 169.

2This process has been variously compared to an interpretive poetic reading and a dramatic realization. For discussions of the former, see Edward Cone, "Words into Music," in Sound and Poetry (ed. Northrop Frye, New York: Columbia University Press, 1957), 3-15, reprinted in Music: a View from Delft (ed. Robert Morgan, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 115-23; and The Composer's Voice (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974), 19. For the latter, see David Lewin, "Auf dem Flusse: Image and Background in a Schubert Song," 19th-Century Music 6 (1982): 47-59 , reprinted in Schubert: Critical and Analytical Studies (ed. Walter Frisch, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 126-52, esp. 127-29.

3In this connection, Don Michael Randel has observed that "much of the best that has been written about recent popular music has approached it from the perspective of sociology and has given a good deal more attention to what the words are about than to what the notes might be about"; at the same time Randel points out that musicology should not be satisfied with a study of the words alone, needing rather to "become a much more active partner in this scholarly enterprise by examining the ways in which the stuff of music (pitch, rhythm, timbre) functions in relation to the social and cultural themes that are more often addressed." See "Crossing Over with Rubén Blades," Journal of the American Musicological Society 44 (1991): 316-17.

4The title cut on the album Graceland, by Paul Simon, Warner Brothers Records 25447-2, 1986.

5See, for example, Edward Cone, "The Authority of Music Criticism," Journal of the American Musicological Society 34 (1981): 1-18; Joseph Kerman, "How We Got into Analysis, and How to Get Out," Critical Inquiry 7 (1980-81): 311-31; Lawrence Kramer, "Hermeneutics and Musical Analysis: Can They Mix?," paper read at national meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Oakland, 1990; Anthony Newcomb, "Schumann and Late Eighteenth-Century Narrative Strategies," and "Once More 'Between Absolute and Program Music': Schumann's Second Symphony," 19th Century Music 7 (1984): 233-50; Gary Tomlinson, "The Web of Culture: A Context for Musicology," 19th Century Music 7 (1984): 350-62; Leo Treitler, "History, Criticism, and Beethoven's Ninth Symphony," 19th Century Music 3 (1980): 193-210, and "'To Worship That Celestial Sound': Motives for Analysis," Journal of Musicology 1 (1982): 153-70; and Martin Williams, "On Scholarship, Standards, and Aesthetics: In American Music We Are All on the Spot," American Music 4 (1986): 160, 162.

6Words and music © 1986 Paul Simon (BMI). I give here the version printed in the liner notes, adding verse and chorus headings, as well as words that are added to Simon's lead vocal in the recorded version; all of my additions are enclosed in square brackets.

7Again, this study recalls Randel's perspective; he comments in "Crossing Over" that "Our approach to the words, too, could profitably give more attention to formal features in relation to thematic content." (p. 317).

8C. O'Brien, "At Ease in Azania," Critical Texts: A Review of Criticism and Theory 5/1 (1988): 37.

9Louise Meintjes, "Paul Simon's Graceland, South Africa, and the Mediation of Musical Meaning," Ethnomusicology 34, no. 1 (Winter 1990): 37-73, esp. 38-40.

10Ibid., pp. 39-40 and 43-47, respectively.