Introduction

Pandit Ravi Shankar is renowned both as performer-composer and teacher. Aside from his acclaimed activities in his native India, for several decades he has offered music filled with poetry and virtuosity to the rest of the world. Our term "improvisation," used to characterize the mysterious blend of spontaneity and tradition in his performances, is notoriously inadequate. It has become debased to refer to spontaneous gestures—sonic, visual, kinetic in medium, beautiful or offensive in effect—as though they exist only in the moment. When spontaneity and tradition meet, when "improvised" gestures occupy a moment within a heritage of expectations, however young or ancient, then improvisation can take on its full mystery in time. Such usage comes closer to describing a central aspect of Ravi Shankar's gifts to us as composer-performer.

As a teacher, he has long demonstrated twin commitments: to carry on the best heritage of a tradition, and to nourish the growth of students, whether they are disciples or connoisseurs listening to recitals and recordings. When, as in his case, the tradition and the commitment are as powerful as they are, one might speak of "missionary" rather than teacher, while hoping to avoid the dominator-dominated abuses associated with the history of that quasi-religious term. One of his artistic "lessons" dates from the mid-1960s: a recording with the noted drummer, Ustad Alla Rakha, of a relatively brief performance of "Raga Puriya Kalyan," containing essential elements of a central instrumental tradition of Northern India in about twelve minutes of clock time.1 In several other compositions recorded on the album, the violinist, Yehudi Menuhin, joins Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha. The artists' expressed purpose in making this anthology, along with its successors, East Meets West II and East Meets West III, is to demonstrate the related nature of some relatively unfamiliar styles from Eastern Europe and India, and to present Menuhin as a violinist in both European and Hindusthani styles.

This present study uses Raga Puriya Kalyan to study music traditional in a large area of the Indian sub-continent. The broad name for the predominant culture of this area is "Hindusthani." There are several languages and religions, and a number of racial and other distinctions. Despite such variety, many people in metropolitan centers such as Delhi, Calcutta, and Bombay enjoy this classical tradition on recordings and broadcast recitals from All-India Radio and Television, and in public recitals. Wealthy people also enjoy private performances in their homes. Many music lovers in India are connoisseurs of this music. Listening with hushed, reverent attention, they are apt to murmur occasionally in spontaneous admiration at an especially poetic or virtuosic passage. Art is deeply rooted in spiritual life; therefore, aesthetic experience of theater, music, and dance becomes a spiritual purifying and opening-up of a present moment into the broad span of time, beyond mere entertainment.

The attractiveness of North Indian concert music is demonstrated by the international fame of such an artist as Pandit Ravi Shankar. Response to his music by Euroamerican audiences, who may lack refined awareness of either its stylistic features or its cultural background or both, speaks of human potential for global awareness.

From a global perspective, it is no longer appropriate to refer casually to North Indian concert music as "foreign," "exotic," or even "non-Western." Is Mozart "Non-Eastern?" The term "ethnic music" can also mislead. Are not Beethoven and John Lennon "ethnic"? The term is useful mainly if it reminds us that besides being moved by any sound-as-music—whether from long ago or today, from far away or nearby, from our earthiest or most sublime aspects—we can also reflect to our benefit on its cultural context. Through doing so, we gain new understanding of the ways of all human beings, not least of all ourselves as co-pilgrims.

The following material offers: (1) information about both style and cultural context of North Indian concert music; (2) analysis of an example of North Indian instrumental music; (3) a framework for guiding contemplation later on, after having experienced other examples in this and similar styles. It also offers descriptions of ways for both individuals and small groups to sound some excerpted examples drawn from the style. Studying this material can lead not only to intensified appreciation of North Indian music but also to insights into a highly cultivated spiritual tradition.

"Raga" and "Tala" are twin terms crucial to an understanding of North Indian concert music. Raga or Rag (pronounced RAH-gah or RAHG) refers to tonal organization of Indian concert music, both in Northern or Hindusthani, and Southern or Carnatic styles. The prevailing texture is a single melodic line with drone plus rhythmic patterns provided by a drummer. Besides referring to a piece for performance, partly spontaneous, partly pre-defined, raga refers both to tonal aspects of the melodic line and to the cultural context in which people experience ragas. "Tala" refers to rhythmic organization, treated later on in this material.

Aspects of raga:

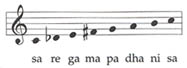

(1) Performers of the melodic line use only certain pitches, conceived as integral to a particular raga, and belonging, either entirely or in part, to a "parent scale."2

(2) Performers emphasize either the "lower" or the "upper" part of the scale. Sometimes "lower part" refers to lower sa through higher pa (Do through Sol), sometimes from lower sa only through higher ma (Do through Fa). Whichever alternative obtains, the upper part completes the scale through upper sa.

(3) Performers develop melodic gestures in which:

A. certain pitches occur more often than others as goals of motion;

B. certain pitches consistently carry ornaments of various kinds;

C. in particular ragas, certain pitches might occur only in rising or in falling melodic contours;

D. in particular ragas, certain groups of pitches might recur in the same sequential order, forming predictable melodic contours.

(4) Performers choose a raga appropriate to a particular season of the year and segment of the 24-hour cycle. Under the influence of evening public performances, the tradition of performing certain ragas only at certain times of day is diminishing. Perhaps it was never strictly observed, but was merely an indication when particular moods, influenced by one's environment, would likely resonate strongly with particular melodic gestures.

(5) Performers choose a preferred mood or range of moods to evoke through a performance. The ancient doctrine of RASA (pronounced RUH-suh) refers to states-of-being, moods, believed to be vital energies in human beings. Nine basic rasas are often listed in the following order, as translated from Sanskrit: erotic, comic, compassionate, furious, heroic, fearful, disgusted, awed, and tranquil. The doctrine offers a striking partial analogy with the baroque Doctrine of the Affections.

An Analysis of a Recorded Raga:

"Raga Puriya Kalyan" ("POO-ree-yuh KAL-yahn") with Ravi Shankar, sitar, and Alla Rakha, tabla, lasts eleven minutes, thirty seconds.

Note to the reader: Listen to the music before reading further. There are two reasons for doing so: first, this analysis presupposes experience of the music; second, your personal response to the raga will almost certainly be diminished by conscientiously seeking too soonto match the music with the analysis. I urge you, before continuing to read this analysis, to consider listening at least twice in a receptive mood, free of conscious analytical concern!

Listen to Raga Puriya Kalyan:

The recording is available through the kind permission of Angel/EMI records and Ravi Shankar.

Time-Line Graphic Analogs:

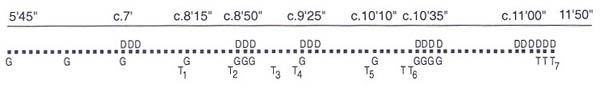

Four times in the course of this study, a horizontal line represents the 11'30" duration of this raga, becoming a "time-line" of successive musical events, on a linear plane reading from left to right. Below each time-line, I indicate either the beginning or end or both of each relevant musical event, and offer explanatory comments.

Time-lines found in this study:

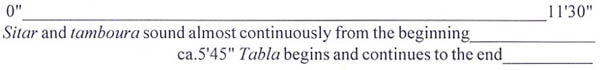

1. Growth as defined by sources of sound

2. Growth as defined by rhythmic qualities of movement

3. Growth of the alap in further detail: its growth as defined by registral changes and cadences

4. Growth of the gat in further detail; its growth as defined by various musical features

Time-Line #1: Growth as Defined by Sources of Sound

Definitions and Commentary on Time-Line #1:

SITAR (pronounced SIH-tar): For hundreds of years the sitar has been associated with Hindusthani music. A plucked stringed instrument,comparable to instruments of the lute family, it has five strings over a fretted fingerboard, two drone strings alongside, sympathetically vibrating strings underneath, and gourd resonators at each end. A player sits on the floor, holding the sitar rather like a guitar, and plucks the strings with a metal plectrum on the right-hand index finger. The curved metal frets allow a performer to change an initial pitch by pulling the string to one side after plucking it.

TAMBOURA (pronounced tahm-BOO-rah, and spelled variously in transliteration): The tamboura is also a lute-like stringed instrument, with a large gourd at the bottom, sounding an unchanging drone. A seated performer holds it vertically in the lap. Its fingerboard is unfretted, with four to seven strings tuned to at least two octaves of sa (Do) and usually to pa (Sol), eitherabove or below sa. Occasionally present is ni (Ti), a minor second below sa, giving a slight, poignant dissonance. The strings are always played at their full length with right-hand fingers. Threads placed between the strings, the gently curving bridge, relatively loose tension, and the large gourd at the bottom allow the strings to resonate quite long, creating a soft, delicate, shimmering sound. A tamboura player sits behind sitar and tabla players, subordinate to their music yet embodying eternity in sound, allowing interplay of their sounds with the drone. In most recitals all three performers sit on a beautiful carpet on a raised dais, with incense perfuming the air.

TABLA(pronounced TUH-bluh): The tabla is a set of two single-headed drums, one smaller and higher-pitched than the other. The smaller drum is usually tuned to sa (Do), although occasionally to pa (Sol)above sa. The larger drum, quite flexible in pitch, serves as the bass. Together the two are the source for a drummer's tonal-rhythmic patterns. They produce many different sounds as a performer either taps with fingers or strikes with the whole hand, and perhaps presses with the base of the palm either in the center, midway out, or at the rim of the drum. The tabla rests on small round cushioned supports in front of the player, who is seated cross-legged beside the sitar player.

Time-Line #2: Growth as Defined by Rhythmic Qualities of Movement

Definitions and Commentary on Time-Line #2:

ALAP(pronounced "AH-LAHP": Alap is a section at the beginning of most raga performances. It is characterized by:

(a) a soloist's changing individual pitches and pitch contours, within a melodic framework prescribed for the raga, with only the background of the constantly sounding tamboura drone;

(b) gradually higher registers through at least two octaves;

(c) phases of movement of various lengths, each arriving at an important pitch in the raga and signalling that arrival by a cadential pattern in the melody;

(d) freedom from meter or even a steady pulse, with enough long durations at the beginning to evoke a quality of slow, dignified movement.

Connoisseurs particularly value an artist capable of evoking a serene mood in performing alap, like "a flower unfolding against the backdrop of eternity." Sometimes alap is performed as a complete piece; at other times, depending on the mood desired by the performers, it is extremely short, presenting essential features of the raga in a few gestures.

JOR (pronounced to rhyme with "door"): Optionally after alap comes another section called jor. In this performance Ravi Shankar moves into jor almost imperceptibly—and beautifully—after what sounds like merely another cadence in alap, a steady pulse becomes audible, signalling jor. Pulse in jor results both from plucking drone strings and from simpler durational ratios in the melodic tones. Phases of movement increase in length, pitch contours sweep through broader musical space, more and more short tones develop momentum; and although there is only steady one-plus-one-plus-one of the pulse, exciting cross-rhythms develop to a climax before the next section. Early in jor of this raga, Ravi Shankar quietly doubles plucking speed of the drone strings, increasing pace and intensity.

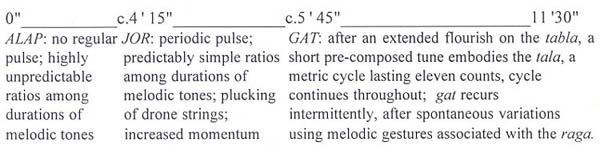

GAT(pronounced "guht"): The term gat refers both to a tune and to an entire section of which the tune is a central aspect. A sudden break in momentum is one of several signals for the beginning of this third section of the performance. Other signals are: (a) the entry of the tabla, which from then on will have patterns based on an eleven-count metrical cycle or tala; (b) a short silence of the sitar, followed by gat. The gat for this performance was pre-composed by Ravi Shankar, possibly to be used only in this recorded performance, possibly to serve also for a number of other performances of Raga Puriya Kalyan. It recurs intermittently throughout the rest of this section, after other more spontaneous melodic gestures. These latter are related to the gat and may refer directly to some part of it. From the beginning of the gat until the end of the performance, increasing excitement comes mainly from quickened pace in the sitar's melodic patterns, but also from complex cross-rhythms, in which either soloist or drummer or both participate.

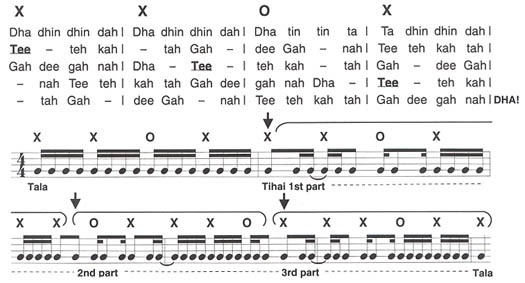

TALA: A tala (pronounced TAH-lah) is a meter. Although many talas exist in theory, fewer than a dozen are common today in Hindusthani concert music. All consist of two or more divisions, each of which will have two, three, or four sub-units. In order to present the tala, a drummer performs: (a) a basic, recurring, skeletal pattern, designed to present the tala in a lively, unambiguous way; (b) virtuosic patterns to give special brilliance and changes in momentum, at the discretion of the soloist, who may choose momentarily to assume a secondary role.

These soloistic passages are sometimes extended patterns of drumstrokes, using both durational and dynamic accents to create a torrent of complex cross-rhythms. Since rhythmic tension builds through several metric cycles, a drummer's virtuosity in concluding precisely on the first beat of a new cycle creates much excitement both in performers and responsive listeners. Each tala contains at least one division in which the larger drum is muted, creating a "tenor" effect with the high drum. This recurrent lift also clarifies the tala for all involved. There are three levels of intensity in a basic pattern: (a) strongest is the first beat of the cycle; and (b) next in strength is the beginning of each of the subsequent groups; (c) least strong are all other beats within the groups.

To experience the powerful interplay of rhythms with the tala, a connoisseur: (a) recognizes the basic cyclic drum pattern, and (b) keeps time bodily, parallel with the tala, whether the music affirms that response or makes cross-rhythms with it. In India, it is customary to continue throughout a performance responding systematically and visibly to the tala. This is traditionally done by: (a) first, clapping palms lightly together, or lightly slapping palm against thigh; (b) then, bringing thumb and the necessary number of fingers successively together, beginning with the fifth finger. Within each cycle, at the beginning of the "tenor" drum group, it is customary to wave the open palm in a quarter-circle clockwise motion, just above the thigh. Such systematic, overt bodily response intensifies the connoisseur's experience, bordering on ecstasy.

The present performance is in a tala called "Char Tal Ki Sawari." Within its metrical cycle of 11 beats, the groups are commonly described as being 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 11/2 + 11/2four quarters followed by two dotted eighths—, or 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 3 + 3—four groups of four sixteenths followed by two groups of three sixteenths.

Example 1. The interplay of durations and pitch contours in both sitar and tabla in this metrical cycle is as follows:

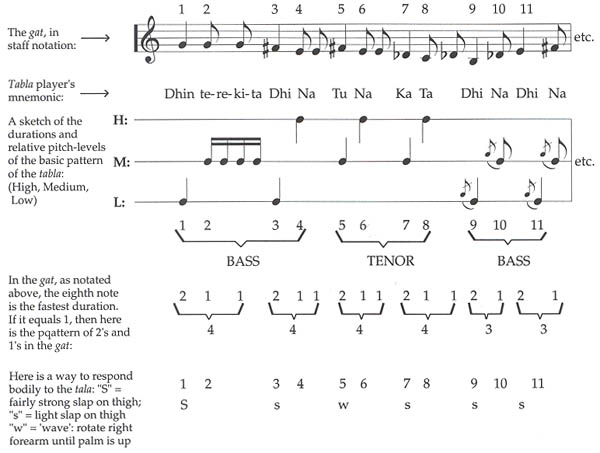

On the staff below in Time-Line #3, each vertical line indicates the end of a segment within alap. Successive mid-range sections of alap are articulated by a cadential figure. It consists of sa (Do) sounded several times, mingled with one or more soft, rapid brushes across the drone strings. Each such cadence serves both as arrival and as a breath joining two successive gestures.

Time-Line #3: A Closer Look at Alap—Its Growth Defined by Registral Changes and Cadences

The parent scale for Raga Puriya Kalyan differs from the Ionian-Major scale by having: (a) a half-step above sa (Do); (b) a half-step below pa (Sol). Thus, if C serves as sa, as it is on this recording, tones of the parent scale are:

This scale, conceived of as a cluster of tonal energy, leads to considerable intensity around sa, surrounding it on both sides by half-steps. Although pa (Sol) has a half-step below, it has a whole step of dha (La) above. Thus the total effect is of decided sa-centeredness. Ga (Mi) evokes a sense of repose, blending with the pure fifth interval of the drone.

F-sharp and D-flat are audible, yet during alap are never held steady. Several distinct kinds of ornamental tones occur as vital elements in performances on sitar. In various ways they combine initial plucking of a string by a right-hand finger with, for instance:

(a) sliding a left-hand finger to another pitch,

(b) stretching the string sideways with left-hand fingers,

(c) plucking the string again lightly with a left-hand finger while lifting the finger from its position at the initial plucking,

(d) striking a string forcibly with a left-hand finger to produce a sound.

These embellishments, each of which has a name, alternate with sounds free of vibrato yet enlivened by sympathetically vibrating strings mounted under melodic and drone strings.

Cultivated listeners will recognize by ear features distinguishing this raga from its parent scale. Deriving a particular raga from a parent scale is sometimes easy, but in this present instance there is ambiguity, since this raga was created by blending the melodic characteristics of two other ragas. Despite its title, "Raga Puriya Kalyan," tones in this raga are those in the parent scale Marwa3rather than Kalyan, our Lydian.

One can respond intensely to light-and-shade, tension-and-release evoked by Ravi Shankar as he unfolds this alap in performance. Numerous "bent" pitches, especially apparent prior to arriving at cadential sa, might at first be unsettling, almost disorienting one's security in pitch. With continued receptive listening they can become beautiful in their approach-avoidance to an important pitch that finally arrives, absolutely pure in its consonance with the drone. Witnessing a great artist in person, observing soft movements of head, torso, even the whole body, can give clues to the mood resonating in such passages.

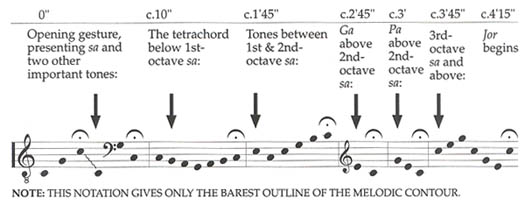

Time-Line #4: Growth of Gat as defined by:

(A) Reappearances of the pre-composed tune,

(B) Interplay of sitar and tabla, and

(C) Presence of tihais

In the above time-line, each dot represents one tala cycle. There are seventy-seven such cycles in this performance. At the beginning of the gat section in this performance the tune appears only once, whereas often it immediately appears twice, helping listeners become acquainted with it. It then recurs in single presentations an additional five times, indicated on the above time-line by single appearances of "G," standing for "Gat." As indicated on the time-line, it also recurs in multiple successive presentations, once for three cycles, once for four.

Except as indicated on the time-line by a "D," standing for "Drum," the tabla player plays the basic pattern during each cycle of tala. At those exceptional times the drummer becomes soloistic in extremely rapid passages. During such presentations, the sitar plays the gat melody to keep the tala clear. Quite often only the beginning of the gat melody reappears throughout the section, keeping listeners reminded of its identity, after which the soloist moves into a free variant for the rest of the cycle. As the end of the performance approaches, both drum and sitar become free of the basic pattern, offering a brilliant climax.

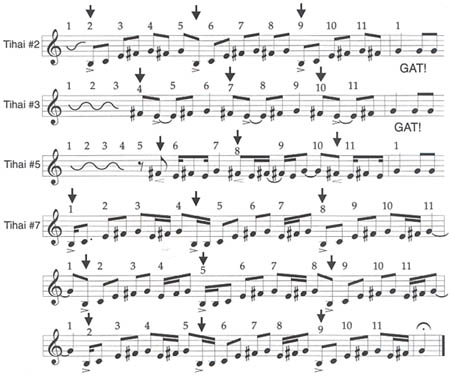

TIHAI (pronounced "tee-high"): A tihai4 is a particular rhythmic gesture in metrical concert music of North India. It might occur in any tala, and signals the approach of a relatively important event in the piece. It does so by repeating three times a gesture designed:

(1) to make an extended cross-rhythm with the established tala;

(2) to end on the first beat of the tala cycle which also marks the beginning of the new event

Seven tihais occur in this performance. Here are notations of four.

D. A Summary of Features Present in This Performance and Also Likely to Occur in Other Performances of Hindusthani Music.

(1) A soloist on the sitar; a drummer, using the tabla, serves generally as accompanist but sometimes as soloist; a tamboura player provides a constant drone.

(2) The soloist emphasizes particular pitches and de-emphasizes others, both individually and as parts of recurrent melodic contours.

(3) Large-scale growth results in two parts: alap and gat. Occasionally alap will occur alone as a complete piece in a full recital, because of its venerated capacity to evoke high states-of-being. Occasionally alap will be extremely short. Generally the two parts are more nearly equal in duration. A predictable length might be about twenty minutes; but if the artist senses unusual inspiration and strong rapport with the audience, it might be at least twice as long.

(4) Within gat, a basic drum pattern repeats as a way to make the tala clear. Periodically the soloist may signal the drummer to become soloistic for one or more cycles of tala.

(5) Increasing intensity results from various causes, eventually forming a climactic conclusion of the performance.

E. Other Features Not Present in This Performance But Likely to Be Part of a Raga Performance in the Hindusthani Style:

(1) Other kinds of solo instruments:

A. SAROD (pronounced Sah-RODE): a plucked string instrument, similar to sitar, but with a fretless, metal finger board, and played with a plectrum traditionally made from coconut shell.

B. SARANGI (sah-RAHN-ghee): a bowed string instrument, fretless, with three gut strings and many sympathetically vibrating metal strings. The player's fingers move along the sides of the strings, rather than pressing them against the finger board, a technique resulting in a bittersweet, disembodied sound.

C. BANSURI (BAHN-suh-ree): transverse flute, made of varying lengths of bamboo for high or low range, with only open holes.

D. HUMAN VOICE, either male or female adult.

(2) A section called JHALA (JAH-luh), in which extremely fast pace results from rapidly plucking drone strings, alternating with a melodic line. Jhala occurs as final section either of a long alap or of gat, as a climax to the performance of a raga.

(3) A technique called JAWAB-SAWAL (JAH-wahb-SAH-wahl), in which the soloist performs a series of relatively short, improvised melodic gestures, some of which form extremely complex cross-rhythms with the tala, and each of which the drummer, while keeping in touch with the tala, must imitate rhythmically immediately afterwards, complete with cross-accents. The length of gestures decreases through time, heightening tension until both soloist and drummer perform a brilliant climactic jhala.

(4) A change, partway through gat, either of tempo or even of tala as well. Traditional names for tempo in the Hindusthani concert style translate into English as: slow, medium slow, medium fast, fast, very fast. Although there may be a simple ratio, such as 2:1, in a change of tempo, it is important to distinguish change of "pace" from change of "tempo." Change of pace can occur by means of the following feature, for example, traditional in this style: the soloist, while maintaining the same tempo, performs a given pattern first at one speed, halves it, then doubles or quadruples it.

(5) Either of two other kinds of composition, DHUN (pronounced DOON) or THUMRI (TOOM-ree), might occur at or near the end of a full recital of Hindusthani concert music. They both have in common a considerable relaxation of the strict preliminary choice of available pitches. The performing artist will evoke changing moods through introducing melodic contours associated with other ragas, instead of steadily developing the single mood of one raga. Well-known traditional tunes might even occur in passing, alongside more spontaneous melodies.

(6) A performance for tabla solo, an optional interlude in a full recital, as a chance to hear the drummer more fully. During such a performance the main soloist would probably play a short tune over and over through the entire piece, perhaps with slight variations, as a lively way of making the tala clear. Another probable feature might be reciting by the drummer of traditional drum patterns, using various syllables, then performing them immediately on the drum.

F. Suggested Activities Related to Hindusthani Musical Style:

1. Provide yourself with a continous drone of two tones serving as Do and Sol (sa and pa). For instance, two or more other people might hum the drone, or use a bowed string instrument, an organ, or a tape loop with synthesized sounds. Choose a group of pitches with which to perform spontaneous melodic gestures, exploring the energy in those tones in relation to Do and Sol. For this purpose it is important to exclude other pitches than those you choose ahead of time. Develop expressive qualities through such techniques as: (1) varying loudness on single tones and at various times during a melodic gesture; (2) humming with open as well as closed lips; (3) varying the amount of vibrato from slow to fast, narrow to wide, to none; (4) using an approach-avoidance technique above and below Do and Sol, delaying resolution into them; (5) change from free rhythm, with highly unpredictable ratios among durations, to a steady pulse or even to a metrical structure, if you are ready for such a complex of elements.

2. Here are some patterns of pitches; feel free both to transpose them to any convenient level, as long as the drone shifts with them, and to add sharps or flats to all except Do and Sol :

PENTATONIC:

C D E G A C (variants: C D Eb G A C, C D E G Ab C, etc.)

C D F G Bb C (variants: C Db F G Bb C, etc.)

C D F G A C (variants: C Db F G Ab C, etc.)

HEXATONIC:

C D E F G A C (variants: C D Eb F G Ab C, etc.)

HEPTATONIC:

C D E F# G A B C (LYDIAN/KALYAN)

C D E F G A B C (IONIAN-MAJOR/BILAVAL)

C D E F G A Bb C (MIXOLYDIAN/KHAMAJ)

C D Eb F G A Bb C (DORIAN/KAFI)

C D Eb F G Ab Bb C (AEOLIAN-MINOR/ASAVARI)

C Db Eb F G Ab Bb C (PHRYGIAN/BHAIRAVI)

The six heptatonic modes listed here occur in both Hindusthani and Occidental traditions.

3. Below is a tihai, notated both in a contemporary North Indian style and in staff notation. It is in TINTAL (pronounced TEEN-tahl), a tala of sixteen beats, 4+4+4+4. The traditional drum pattern for tintal is:

X 5 4 3 X 5 4 3 0 5 4 3 X 5 4 3 Dha dhin dhin dha Dha dhin dhin dha Dha tin tin ta Ta dhin dhin dha

These letters and numbers refer to the system of counting as explained above. In performing the pattern quickly, only the claps and wave are used. Perform the tihai, either by yourself or in a group. First, establish a basic pattern and tempo with the following first line, then continue into the tihai, here spelled phonetically:

Tihai notated with mnemonic syllables and in staff notation:

NOTE: "0" means a silent count. "DHA" at the end of this tihai is the beginning "Dha"of the next cycle beyond. In performing, emphasize those syllables beginning with a capital letter, indicating the start of a rhythmic group.

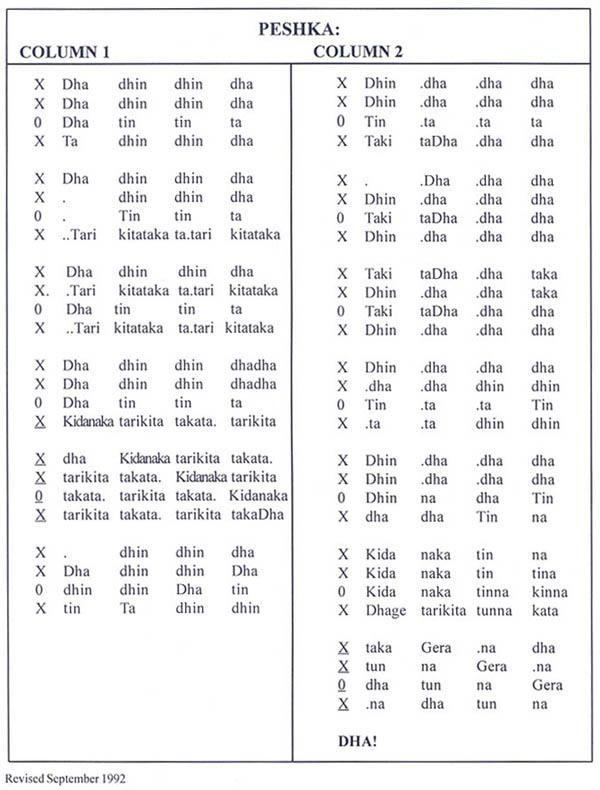

4. Below is a Peshka in Tintal, in a contemporary Hindusthani notation. Mr. Harihar Rao, of Delhi and Los Angeles, kindly provided it. A Peshka is an extended rhythmic pattern for tabla, using a variety of drum strokes to create an interplay of congruent and cross rhythms within a tala. It might be performed either during a raga, when the drummer becomes soloistic, or as part of a complete drum solo. The drummer might first recite it orally during a complete drum solo, then perform it immediately afterwards on the tabla, probably at high speed. It is preceded and followed by the basic drum pattern for tintal, as notated in item 3 above.

Perform the Peshka either alone or with other people, either all together or antiphonally, at various tempos, from quite slow to as fast as possible. Keep the rhythm lively by stressing the beginning of each rhythmic group, indicated by capitalized syllables. At a fast tempo, unstressed syllables containing the vowel "a" tend to become "uh." Pronounce "r" as a "flip r"—almost like a "d"—rather than the "American" rolled "r." The letter "g" is always pronounced as in "go."

In the present notation, each horizontal line in each of two columns equals a maximum of sixteen sounds, laid out in groups of a maximum of four syllables each. If a sixteenth-note in staff notation were to stand for the fastest sound, then each horizontal line could be said to represent four quarter-notes, one-fourth of a cycle of tintal, including rhythmic patterns with combinations of quarter-, eighth-, and sixteenth- note sounds and silences. Thus the dots used below vary in meaning, being used to fill the duration of: (a) a sixteenth in connection with three syllables, (b) an eighth in connection with one syllable, (c) a dotted eighth in connection with one syllable, or (d) a quarter-note when used alone. X's at the beginning of each horizontal line indicate an audible, or at least visible count with the hand; the O's indicate an inaudible wave of the hand, as described above. To experience the full energy of the rhythms, counting in this traditional way is helpful. Underlines indicate the presence of a tihai.

1Angel Stereo 36418, East Meets West I, Library of Congress Card Number R 67-2984.

2There are thirty-two parent scales in Hindusthani theory, some twenty of which are in current use. Each parent scale contains some choice of seven tones out of the twelve approximating our chromatic scale. Since Do and Sol are fixed, possible choices are: Do, Ra/Re, Me/Mi, Fa/Fi, Sol, Le/La, Te/Ti. The Indian names for Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, Ti are: sa, re, ga, ma, pa, dha, ni. Modifications carry also the term "komal" for lowered and "tivra" for raised—e.g., Ra would be "komal ri" and Fi would be "tivra ma." In classical style, any tone not traditionally included in a chosen raga is forbidden. Ancient and contemporary Indian theorists differ on the number of parent scales; in fact, there is little consensus on any aspect of theory. If our major scale becomes a point of departure, the other thirty-one scales derive their structure from raising or lowering one or more tones one-half step; however, neither sa (Do) nor pa (Sol) is ever altered. The following shows sixteen of the thirty-two parent scales; the other sixteen duplicate this list, except all have the fourth degree raised one-half step. In reading the following list, the indication "-7," for example, translates "lower the seventh degree one-half step in relation to the first listed scale, our Ionian-Major; and "+4" translates "raise the fourth degree . . . ."

1.

2.

3.

4.0

-7

-6

-6

-75.

6.

7.

8.-2

-2

-2

-2

-7

-6

-6

-79.

10.

11.

12.-3

-3

-3

-3

-7

-6

-6

-713.

14.

15.

16.2

-2

-2

-2-3

-3

-3

-3

7

-6

-6

-7

The following ten scales are currently most popular. They have ten Hindusthani and six Euroamerican names:

1.

2.

3.+4

0

-7(Lydian/Kalyan)

(Ionian/Bilaval)

(Mixolydian/Khamaj)4.

5.

6.-3

-3

-2-7

-6

-3

-7

-6

-7(Dorian/Kafi)

(Aeolian/Asavari)

(Phrygian/Bhairavi)7.

8.

9.

10.-2

-2

-2

-2-3

-6

+4

+4+4

-6-6 (Todi)

(Bhairav)

(Purvi)

(Marwa)

3See footnote 2.

4The technique called "tihai" suggests an interesting cross-cultural parallel with the hemiola, since in European baroque concert music the latter figure often signals a cadence, and, also like the tihai, "reconditions" the basic meter by a predictable cross-rhythm.