During the last twenty years, a consideration of the roles of women and minorities in musical life has become increasingly central to the study of music. The "canon" of old has proven to have porous boundaries, with works by women composers and by lesser-known male musicians seeping in to join the works that were deemed worthy in the past. The music teacher nowadays may focus on several different but overlapping sets of masterpieces, depending on the context and agenda he or she brings to the classroom. The call to a more inclusive scholarship, and particularly the call to incorporate women into our accounts of the past, has resulted variously in historical anthologies of music by women, a women-in-music textbook, a collection of source readings, a multitude of scholarly publications and bibliographies, and reviews of the role of feminist scholarship and feminist pedagogy.1

Yet in spite of conscious efforts to diversify the core repertory, the earlier periods of music history have proven difficult to revamp. A few token compositions by medieval and Renaissance women now dot the typical music history syllabus, but they do little to convey the breadth of women's musical experience in earlier times. Unfortunately for our pedagogical endeavors, the paucity of surviving evidence generally means that historical narratives must be constructed based on the fortuitous survival of fragmentary evidence, and women and minorities are not featured extensively in that historical record. Moreover, given the past dominance of male composers and the prominence of exclusionary musical institutions, women of the Middle Ages and Renaissance were unlikely, perhaps even unable, to rise to positions at the top of the musical profession. Thus, evidence for the achievements of women and minorities in the field of early music can be difficult, though not impossible, to locate.2

A number of feminist scholars have observed that a discipline moves only gradually from a subject matter that deals exclusively with men to one in which women's roles are fully integrated. As they point out, a thoroughgoing revision of a curriculum usually consists of several distinct phases, phases which reflect both changes in content and changes in methodology. The discussion that follows uses these phases as a framework for understanding the changes in textbook content in music-historical accounts of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, exploring the ways in which the questions which an author or teacher asks affect the relative inclusion or omission of women from the historical narrative. Careful reading shows that women appear at least tangentially in even the most traditional male-dominated chronicle.

The Traditional Paradigm: Middle Ages

At first glance, the near-absence of women in older histories of music of the Middle Ages hardly seems strange. Discussions of medieval music generally focused on stylistic criteria such as mode, the intervals used in early polyphony, and the common forms of the day. Summed up, medieval history might proceed from chant to the achievements of Notre Dame organum, to the largely anonymous motet repertory, and to the accomplishments of the Ars Nova. If musical figures were to be added to an essentially genre-oriented account, music theorists stood side by side with the composers. Guido of Arezzo, Anonymous IV and Franco of Cologne were matched by Notker, Leonin, Perotin, Philippe de Vitry, Machaut, Landini. In these older histories, the secular sphere was represented by the minstrel and the troubadour (with Bernart de Ventadorn as an example of the latter), and a listing of musical instruments commonly rounded out the discussion.

The underlying philosophy of this vision of the past is revealed by its focus on the great work and occasionally the great man. Medieval music history has generally consisted of series of compositions which exemplify the successful new genres of the day with some explanation of how those compositions function and what innovations they exemplify. In this view, there is little room for womanly contributions. Only the Comtessa de Dia's "A chantar" fits the accepted scheme of stylistic development, for it can serve as an example of the troubadour art. The works of Hildegard of Bingen have recently become almost emblematic of women's contributions to the past, but her use of mystical and visionary language and her idiosyncratic musical style brand her works as exceptional, "unusual,"3 extraordinary, or outside of the bounds of "normal" musical contributions. Wonderful they may be, but Hildegard's works form a kind of stylistic dead-end and do not fit well into a narrative scheme which centers on the evolution of genres. The byzantine chant composer Kasia likewise falls outside of the mainstream of western musical history, in her case due to geographical considerations.

Yet the traditional histories of early music have slighted the roles of medieval women in other ways. Until recently, for example, the language chosen by many authors to describe medieval culture unintentionally disinherited medieval women. Insensitive authors included monks but omitted nuns from their narratives; they incorporated minstrels and jongleurs but neglected their female counterparts; they implied (by their choice of examples) that musical patronage was exclusively a male sphere. Since such omissions are fairly easy to rectify, updating medieval music history in order to be more woman-friendly ought to involve a minimum of fuss.

Nevertheless, many textbooks retain the bias of older histories, for the medieval period shares with the Renaissance prevailing cultural assumptions about the role of women in the past. Knowing that women were excluded from universities and from most schools, some authors suppose them to be too uneducated to participate in musical life. Though we recognize that music was largely a sounding art rather than a written one, it is hard to avoid our modern equation of illiteracy with ignorance, and pre-modern women, more than their male counterparts, have been tainted by both labels. Secondly, the fact that the church frowned on women's participation in some public contexts has been falsely generalized to the church's prohibition of women's participation in all circumstances, discounting the significant role that women played within women's monastic communities and in worship at home. Finally, the habits of modern musical life in which art music is equated with written music have obscured the image of a life enriched by a variety of music-making endeavors including dancing, improvising, and unnotated performance in which women and men may have participated equally (all of which are documented in literary and archival sources) in favor of the analysis of specific surviving works of a predominantly male literary culture.

The Traditional Paradigm: The Renaissance

For the Renaissance era in particular, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century conjectures about the place and role of women in music history led to an essential mis-truth which has hindered our efforts as broadminded, socially-conscious musicians to comprehend the past. That mis-truth is that "for 150 years, there were no women musicians." Over time, we have experienced a series of fall-back positions:

- There were no women musicians.

- There were a few women composers, such as Magdalena Casulana and Vittoria Aleotti, but they had little or no influence and do not rank among the best musicians of their day.

- Those few women musicians may have had some influence, for they taught students and served as dedicatees, but they are exceptions, and women in general were not musical.

- Women in general may have performed, but they were only amateurs and so do not count among the musicians of the period.

- Some women (such as the Concerto di Donne) performed professionally, but they are most significant for the way they inspired composers, who developed new techniques and styles in response to their virtuosity.

Since in all of these views, composers form the central and proper focus of music history, and since with a few exceptions there were no women composers, the student might justly conclude that there were no women musicians during the Renaissance, in spite of evidence to the contrary.

Indeed, the dominant paradigm for the teaching of Renaissance music history, like that for medieval polyphony, remains the "great man" hypothesis. It is difficult to imagine teaching Renaissance music without teaching Dufay, Josquin, and Palestrina, often to the virtual exclusion of other composers and topics. In many music appreciation texts, for instance, the contributions of the period can be sized up in a mere handful of musical figures, with an extra page or two detailing the meaning of the term "Renaissance" and the way this "humanistic culture" rejected the blind religiosity of the preceding Middle Ages.

Even in the handful of texts available for our undergraduate music majors, the hero exerts a centripetal force on our historical narrative. In the preface to his textbook, Music in the Renaissance, for example, Howard Mayer Brown describes his aims by posing four key questions:

Quite simply, I wished to write a book that would introduce university students as well as my colleagues in other disciplines and interested laymen to the music of the Renaissance, a book that would answer several fundamental questions: What were the most significant features of Renaissance music? Who were its greatest composers? How were they great? In short, what is there about this music that still makes it meaningful for us today? [emphasis mine.]4

The first of these questions is unexceptional; the notion of identifying salient stylistic criteria certainly informs a great deal of modern scholarship.

The trio of questions which follow, however, are more problematic, for they create the framework for the textbook itself. The answer to the question, "Who were its greatest composers?" is presumably answered by looking at the chapter headings—"Dufay and Binchois," "Josquin des Prez," "Palestrina, Lasso, Victoria, and Byrd," to name a few—and the prose that follows the various headings attempts to answer the question, "How were they great." Brown implies that this very greatness—timeless, universal and, unfortunately, exclusively male—is "what makes [the music] meaningful for us today."5

Brown, like many textbook authors, sets out quite self-consciously to create an invisible hierarchy of winners and losers; the winners are mentioned, while the losers never appear. In the chapter entitled "Josquin's Contemporaries," Brown acknowledges the musical efforts of a number of composers, but does so with a backhanded compliment: "If the High Renaissance was the age of Josquin, his contemporaries nevertheless created an extraordinary body of music worthy to be set beside his." He implies a single standard of "worthiness" which Josquin exemplifies; the other music, though extraordinary, is not quite as worthy, and the efforts of untold hundreds—kleinmeister, amateurs, monastic musicians, women—remain undiscussed.

In this traditional view of Renaissance music history, then, scholarly and pedagogical attention focuses on the singular individual, the composer-hero who anticipates the Romantic figure of the great artist struggling in near isolation. Accordingly, performers and lesser-known composers appear only as adjuncts to the musical craft, whether they be male or female, genteel or lower-class.

Phase Theory

Feminist theorist and pedagogue Peggy McIntosh has characterized such exploration and elucidation of the "worthies" of history as "womanless," for it points to a selected few winners (nearly always men) who meet highly exclusionary standards of excellence; the losers at this stage are invisible. This style of scholarship masquerades as objective and universal, but is in fact, as Florence Howe reveals, political:

In the broadest context of that word, teaching is a political act: some person is choosing, for whatever reasons, to teach a set of values, ideas, assumptions, and pieces of information, and in so doing, to omit other values, ideas, assumptions, and pieces of information. If all those choices form a pattern excluding half the human race, that is a political act one can hardly help noticing.6

What, then, are the alternatives to the "great-man" version of the Middle Ages and Renaissance? How could we construct a woman-based music history for these early periods? McIntosh's "Interactive Phases of Curricular Re-Vision"7 provides a useful point of departure.

McIntosh establishes what she sees as "five interactive phases which faculty tend to undergo as we try to rethink our disciplines":

1. Womanless History

2. Women in History

3. Women as a Problem, Anomaly, or Absence

4. Women as History

5. History Reconstructed, Redefined and Transformed

According to McIntosh, these phases reflect not only a shift in content but also a shift in methodology that will ultimately transform each discipline. In most instances, her first phase reflects the pre-feminist state of the discipline. The second phase then begins to include a few exceptional women to stand alongside their male colleagues. As scholars and teachers add content pertaining to women, however, new questions arise, such as why there is an apparent imbalance between men and women in the historical record. This results in the third phase of curricular transformation, in which the so-called problem of women's absence is acknowledged and in some cases explored. A practical and effective reaction to this "problem" is to generate new questions (and therefore new narratives) which address women's place in the past: if women were not active as composers, what were they doing? Thus, the fourth stage focuses on women's accomplishments, and not merely on their absence. In the final phase, the discipline shifts to a balanced perspective in which historical accounts reflect the activities of both men and women. The practitioner of the discipline, aware that knowledge is historically and socially constructed, would have a far broader view of the methodology and content appropriate to the discipline than most of her pre-feminist forbearers. Fifth-phase music history, for instance, might expand beyond the role of composers and genres to incorporate the study of the ways in which gender influenced music-making, a consideration of the intersection of gender and patronage, and an investigation of the gendered language which contemporaries applied to a particular musical repertory.

"Phases" of Medieval-Renaissance Music History

Those familiar with early music scholarship will be aware that aspects of each of these phases can be teased out of a variety of publications, both pedagogical and professional. The first category of "womanless" history easily encompasses the traditional paradigm of medieval and Renaissance music history, for in both instances history is treated as a competition in which only the winners are mentioned. First-phase scholarship (and pedagogy) ignores the fact that the competition is rigged—the criteria for winning are derived from the works of the pre-selected winners. In music, womanless history is a tale of great composers who establish a central musical language; the story is rounded out with discussions of the various genres in which the great composers excelled—which are by circular logic defined as the important genres: motet, mass, chanson, madrigal.

Second-phase scholarship, with its focus on "women in history," would seek to identify the various women who succeed in the rough-and-tumble world of composer competition. For a range of reasons—access to training, focus of women's musical creativity on improvisation rather than composition, bias amongst the sources, and so forth—very few women victors emerge for either the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. Magdalena Casulana is perhaps the luckiest of the Renaissance "winners"; not only did she write a lot of music, but some of it survives complete. Beatrice Pescerelli's edition and discussion allows us to consider Casulana as a madrigalist.8 Note that Alfred Einstein, in his monumental The Italian Madrigal, however, discusses Casulana only as a dedicatee, not as a composer in her own right,9 and none of the standard music history textbooks consulted for this paper mention her accomplishments.

The third phase of scholarship recognizes the impediments that have blocked women from pursuing the same career tracks as men. The same scholar who provided a composer-oriented and male-oriented narrative for undergraduate music history classes wrote sensitive and thoughtful remarks on the absence of women composers in the early Renaissance in his essay for Women Making Music; Brown's "Women Singers and Women's Songs in Fifteenth-Century Italy" is one of the most accessible discussions of the musical roles women played and the ways in which those roles were circumscribed by gender expectations that has yet been written. Brown points out that ". . . if some noble Italian women of the late fifteenth century did write music, modesty and a sense of decorum would most likely have prevented them from admitting it," for courtiers were not supposed to be visibly proud of their social accomplishments. Moreover, Brown continues, women were prohibited from church, which kept girls from receiving the standard musical training provided to their choirboy counterparts.10 Similarly, Jane Bowers and Judith Tick in their introduction to Women Making Music point towards many of the medieval women who had active musical lives, but conclude their discussion with a telling observation: ". . . it is fair to state that women were excluded from musical positions of high status and lacked direct access to most professional opportunities, rewards, and authority."11

Although the medieval chapter of Karin Pendle's Women and Music: A History by J. Michele Edwards surveys a variety of women's musical roles, Pendle's own contribution on "Women in Music, ca. 1450-1600" concentrates on ways in which Renaissance women were excluded or marginalized from what we consider the musical mainstream, the composition of notated musical repertories.12 Pendle acknowledges that "[a] woman's experience was influenced by her social or economic class as well as by her gender," but she later asserts that "the requirement that society placed on all women in the years 1450-1600 was that they consider marriage, motherhood, and household management their life's vocation."13 In the binary opposition public/private, Pendle suggests, women were trained for the latter, and even exceptional women "were . . . expected to limit their music making to home or court."14

The frustration with "male-dominated institutions"15 remains close to the surface throughout this chapter, even when Pendle discusses the many successful performers of the era. For instance, she decries the fact that "chamber groups like the concerto della donne were never asked to augment the cappella, for that institution and its educational opportunities were reserved for boys and men."16 Though this statement is indisputably true, we suspect that it is an echo of resentment against educational inequalities of modern-day society, for one does not ordinarily comment on historical events that did not happen. McIntosh herself remarks that "phase three work brings anger and . . . disillusionment . . . " as the new thinking "raises questions of how the systems of reality got defined in such a way that women's realities got left out."17

Challenging The Paradigm

What McIntosh describes as "women as history"—her fourth phase—is perhaps the most radical break with the scholarly habits of the past: in phase four, women are evaluated in their own terms; their lives are taken as a part of history and are deemed worthy of study in their own right. In this kind of study, one might explore women's musical affiliations. If they weren't (often) composers, what musical activities did they engage in? What does it mean to be "musical"? In what ways might women's experiences of music differ from those of their male counterparts—or from those of other women? Paula Higgins' 1991 article, "Parisian nobles, a Scottish princess, and the woman's voice in late medieval song,"18 is a useful example of what kinds of discoveries one makes when one changes the questions we ask. Higgins takes as her starting point the four songs with acrostics or puns on the name "Jacqueline d'Aqueville" by Antoine Busnoys. By exploring "the social, cultural and historical contexts" for two different women carrying that name, Higgins elucidates, in her words, "the ways in which Jacqueline de Hacqueville or women like her might have participated in the literary and musical culture of the late Middle Ages."19 In particular, Higgins exhumes evidence pointing to extensive literary activity in the circle of Marguerite d'Ecosse, the first wife of King Louis XI, and points to a new interpretive strategy for approaching anonymous songs in a woman's voice.

While Higgins' stance is clearly feminist—a strategy which has led some scholars to resist her perspective—Anthony Newcomb's well-known study of the concerto di donne is less so.20 Newcomb adopts an "objective" voice, dealing with "the what, where, and when" of the founding of professional women's groups in the 1580s; he then explores, in an equally "objective" voice, the training and social background of these musicians, citing the "subtle forces of chance and custom that prepared women for the musical profession in the 1580s and 1590s."21 He discovers a "shadowy half-world" at the beginning of the sixteenth century in which women in fact did participate in music-making, but he concludes that it was a social change in the 1570s that allowed women's emergence as "highly prestigious women performers and . . . women composers as well."22 Music-making is, in Newcomb's view, to be judged by the criteria that have been used to judge men; Newcomb implicitly claims that only professional musicians—performers and composers—truly matter.

Newcomb's study reveals that, in Elizabeth Fox-Genovese's telling phrase, ". . . adding women to history is not the same as adding women's history."23 Nevertheless, Newcomb's material can readily be adapted to a phase four perspective. By validating the nonprofessional musical role adopted by the female forbearers to the concerto di donne—by treating that role as an appropriate focus of scholarship in its own right and not just as an antecedent to some professional development—we would create a more detailed picture of musical life of the sixteenth century.

In fact, much of the cultural and archival work on medieval and Renaissance music history can be adapted to phase four scholarship. Digging through the secondary literature on life at court, for example, one can find numerous examples in which women participated in discussions on music, or owned music books. Is that part of music history? Clearly the answer is yes, if history is to take into account the place of music in society. One of the most exciting things about the feminist historical paradigm is that it asks inclusive questions about the place of music in society at large as well as the ways in which gender expectations shaped the creation and consumption of that music. Similarly, a phase four approach to the history of Renaissance would challenge the "amateur" status accorded to nonprofessional music-making since it encrypts a set of assumptions that are neither appropriate to nor particularly revealing about music of the past. At what point does a musician—of either sex—become professional? Is it after the first payment for musical duties? After they have been hired for a season? For a year? Permanently? If a benefice for a male singer reflects payment for clerical rather than musical responsibilities, is his musical role "professional"? If a composer such as Rore publishes a book of music and does not get paid, is he then an "amateur musician"? Is it only after publishing a second collection of madrigals that one is, in fact, a "true musician"? Does your first book retrospectively become a "professional's" repertory? The label "amateur" provides a facile dismissal of the activities of the majority of our musical ancestors; it is a label that should be handled carefully.

Curricular Transformation

If we merely include a discussion of the presence or absence of the female composer of the Middle Ages or Renaissance in our mainstream music history classes, we do a disservice to our understanding of the past. These women performed both composed and improvised music, they maintained a flourishing musical culture at convents, they participated in the elite audiences which shaped musical tastes, and they served as patrons for the efflorescence of secular music during the period. How then could we construct what McIntosh envisions as the fifth phase, a "reconstructed, redefined and transformed" history which includes us all? How can

we invent . . . a curriculum which socializes people to be whole, balanced and undamaged, a curriculum which includes rather than excludes most parts of life and which both fosters a pluralistic understanding and fulfills the dream of a common language.24

In large measure, we can create such a history by teaching not only about composers and performers—and the social constraints placed on them—but also about the roles of publishers and copyists, dancers and poets and patrons, teachers and book-owners, improvisateurs, men and women religious, audience members and critics. This music history class would address the issue of why some music was written down and other music was not. It would teach the polyphonic mass, but would also teach the role of the Catholic Church in the lives of peasants in the fifteenth century and the changes wrought by the Protestant Reformation. In this music history class, the teacher, like the students, would come to recognize the place that music had in society then—and the place that it has now.

Above all, an integrated music history would pose a variety of questions about the historical figures, both male and female, that populate our historical record. There is room in this curriculum for composer biography, but questions about social identity (gender, class, master/apprentice, etc.) might usefully complement questions about cities visited and salary garnered. The history of musical style might address issues of patronage and audience. Thus, an integrated music history is a culturally centered history in which the same work (or same figure) can generate myriad questions, depending on one's perspective and one's goals.

Resources For a Balanced Curriculum

A quick glance through the standard music history textbooks proves that the incorporation of women into our historical narratives is an unfinished process: women composers appear only occasionally in the main body of the texts and are listed only sporadically in their indices. Unless one plans to buy a second, women-oriented textbook, the teacher him- or herself must plan carefully to integrate women successfully into a discussion of early music. Nevertheless, the materials that are necessary for a balanced presentation in which gender plays a part are readily available—often in the same textbooks which seemingly ignore or downplay women's history.

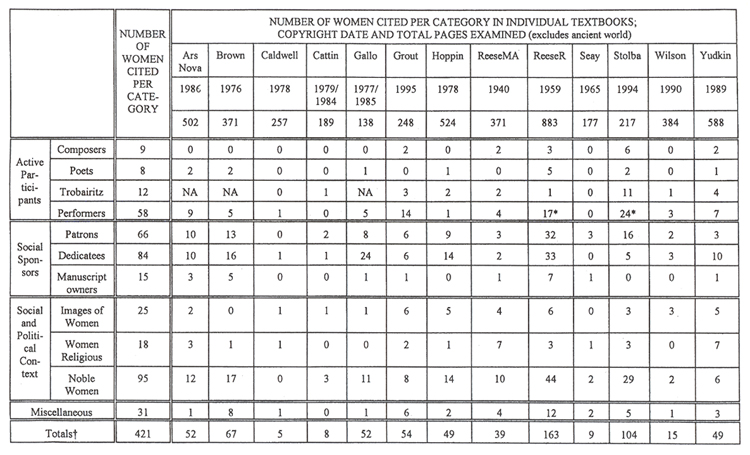

We chose to survey thirteen textbooks intended for undergraduate music history courses which addressed Medieval or Renaissance music, omitting specialty texts like Women Making Music and Women and Music: A History, to determine how often (and in what contexts) women were mentioned. These references to women were then categorized and counted to identify trends in the inclusion of women. We looked for a broad range of possible roles of women in musical life, but have included only those categories for which we could find textbook examples. The category of publisher/printer, for instance, is excluded from our tally because only one such woman was mentioned in the textbooks examined here.25

The most remarkable finding of our survey is that these textbooks, though generally slanted towards a male perspective, always mention women in one context or another. Far from being negligible, women appeared consistently in a variety of roles; all told, we identified 257 different women and women-related topics. Yet our readings of these texts suggested that their perspective was biased: the number of women mentioned did not necessarily correspond to a "woman-integrated music history." (See Table 1.) In fact, we found that in these textbooks, women served an important role in evoking social and political conditions; the category sporting the broadest array of historical figures was that of noble and political women, while women patrons and women dedicatees were also prevalent in the narrative fabric. Sources were less generous, however, in their discussions of women who participated actively in musical roles. Fewer than half of the sources mentioned a woman composer, and many sources mentioned only a small handful of women performers. We were surprised to find that none of the sources made more than a passing reference to nuns, for instance, and were taken aback to discover that neither Magdalena Casulana nor Vittoria Aleotti were mentioned in any of the texts under consideration. Nevertheless, we were heartened to discover that these textbooks provided the materials for a nuanced understanding of the historical past; we identified 421 different "exempla"—individual women (or topics) illustrating the various categories of musical participation.

Table 1: References to women in selected music history textbooks

* ReeseR and Stolba list Tarquinia Molza both as a performer and a conductor; these entries, however, have only been counted once.

The total number of references to women's musical activities per book (listed under "totals" at the bottom of the table) is usually higher than the actual number of women cited in that book since the same woman may appear under multiple headers (e.g. as patron and noble woman). Each woman is counted only once per category, however, even if extensive discussions of her impact can be found in two or more portions of the book.

ABBREVIATIONS:

ArsNova

Brown

Caldwell

Cattin

Gallo

Grout

Hoppin

NA

ReeseMA

ReeseR

Seay

Stolba

Wilson

YudkinDom Anselm Hughes and Gerald Abraham, Ars Nova and the Renaissance, New Oxford History of Music, vol. 3, Oxford University Press [1986]

Howard Mayer Brown, Music in the Renaissance, Prentice Hall, 1976

John Caldwell, Medieval Music, Indiana University Press, 1978

Giulio Cattin, Music of the Middle Ages I, trans. Steven Botterill, Cambridge University Press, 1984

F. Alberto Gallo, Music of the Middle Ages II, Cambridge University Press, 1985

Donald Jay Grout and Claude V. Palisca, A History of Western Music, 5th ed., W.W. Norton, 1996

Richard H. Hoppin, Medieval Music, W.W. Norton, 1978

Not applicable

Gustave Reese, Music in the Middle Ages, W.W. Norton, 1940

Gustave Reese, Music in the Renaissance, rev. ed., W.W. Norton, 1959

Albert Seay, Music in the Medieval World, 1st ed., Prentice Hall, 1965

K. Marie Stolba, The Development of Western Music: A History, 2nd ed., Brown and Benchmark, 1994

David Fenwick Wilson, Music of the Middle Ages: Style and Structure, Macmillan, 1990

Jeremy Yudkin, Music in Medieval Europe, Prentice Hall, 1989

As can be seen in the table, relatively few of the women known to have participated actively in music making were included in any single textbook prior to the mid-1990s, with the exception of the two volumes by Gustave Reese. This absence is significant because there are more known women composers and poets, trobairitz and jongleuresses, and women performers in general than were shown even in the most progressive text. In other words, we found that most of the textbooks adopt a phase-one or phase-two perspective, in which only "great" composers, mostly male, are mentioned, and significant women are mentioned as token representatives of their sex. This bias corroborates the earlier findings of Diane Jezic and Daniel Binder, whose "Survey of College Music Textbooks" in 1985 investigated the incorporation of women composers and their works into both music history and music-appreciation textbooks.26 They found that "the representation of women composers in some of the most recent texts [is] no better and sometimes worse than those published earlier" and concluded that "the task of this generation is to write a history in which women composers and their music are no longer ignored, or worse, trivialized."27 Our review of more recent texts suggests that this task remains undone.

Somewhat ironically, given the relative absence of women composers and performers, we found that textbook authors are reasonably likely to acknowledge women's role as patron, dedicatee or noble/political figure. Such references were sometimes couched in biased language. Often only a man's patronage was stipulated, for instance, even though a woman who likely partook in the same activity (a wife, daughter, or betrothed) was mentioned in the same general context. To cope with this textual ambiguity, we have included women who were merely mentioned by textbook authors as wives of male patrons in our category of "noble/political women" since their patronage was not specifically mentioned. Wedding music, however, we assign to both husbands and wives (even if the author suggests that the composition was intended for the man) listing such references under the header "women as patrons."28 In other cases, specific women were mentioned as culturally significant, but their ties to music were not clarified in that particular textbook. For example, individual women rulers such as Eleanor of Aquitaine and Elizabeth I of England whose patronage was discussed extensively in some texts were mentioned elsewhere without reference to their musical patronage. By reading broadly, we find that many of the women who are mentioned in textbooks merely to provide a "scenic backdrop" for the musical activities of the time might in fact fit into one or several of the musically-involved roles, since wealthy noble women were more likely than their non-noble contemporaries to serve as patrons, and patrons were more likely to be named as dedicatees. Even a passing mention of a woman, then, gives the reader a clue to women's involvement with the music of their time and may serve as a point of departure for further research. In sum, the prevalence of women mentioned in these "supporting" roles enables a phase-four historical discussion of what women accomplished in musical life even if the text itself adopts a composer-oriented focus.

If some texts seem to reflect phase-two scholarship, treating only "great" women, and others reflect phase-four scholarship, treating women "as history," none of the textbooks intended for general undergraduate music history classes could be labeled definitively as phase three, for none mentioned the absence, problem, or anomaly of women in music history. Some authors seem to be unaware of the relative absence of women in their version of the past, while others have addressed the imbalance between men and women by seeking out examples of the latter. Whatever their attitude towards inclusiveness, mainstream authors do not offer explanations to the modern student about why women appear so rarely in the history of early music. Such explanations can be found readily, however, in books intended for women-in-music classes as well as some collections of essays centered on the women-in-music theme. A phase-three textbook may not be necessary to a diverse curriculum, but the issue of access to training and to performance opportunities affected historical men as well as historical women; such an issue could easily be used to place successful composers and performers into a broader historical context. Perhaps the eventual inclusion of different kinds of questions—the reevaluation of the discipline as a whole—will make overt questions about "why women weren't [often] composers" redundant.

Cautions and Caveats

In our sampling of textbooks, it is apparent that more could be done to include women in early music history, but some of the important questions about the place of women and of men in musical culture can now be addressed in class. Indeed, we were pleased to discover that women are already a larger component of our music history narratives than the mere listing of women composers would lead us to believe, for the women portrayed in these texts undertook a variety of roles in the musical life of their time. Nevertheless we hope that textbook editors, authors, teachers and members of the discipline as a whole will continue to expand their approaches to gender issues. As we do so, we should beware the token inclusion of women. Many of the textbooks merely mention a woman's name in passing, devoting little if any space to a discussion of her contribution to music history. Any mention is better than none at all, but a true understanding requires context and depth. Second, we should not be made complacent by recent strides towards including women, for the materials for a woman-friendly music history were available to Gustave Reese in the 1940s and 1950s. Though the fifth edition of Grout provides examples of women in nearly every category addressed by other textbooks and so improves upon the fourth edition (which did not even mention Hildegard of Bingen, for instance), the period-specific textbooks still have a far distance to go to catch up with this pedagogical trend towards diversity.

Finally, efforts to create a gender-integrated music history are hampered by the very textbook indices intended to direct the reader to significant people, places, and things. The textbooks surveyed uniformly obscure the roles of the women which they include by omitting categories that would allow readers to track women's contributions, and, in all too many cases, omitting the women themselves.29 Indeed, authors who have put effort into incorporating examples of women in musical life might easily go unrecognized if only the textbook index were consulted. F. Alberto Gallo's Music of the Middle Ages II, for instance, discusses Solage's compositions for Jeanne of Boulogne and Catherine of France, but omits both women from the index even though two ballades for Catherine mention her through an acrostic.30 Authors need to be certain that women, as well as their husbands, brothers, and fathers, appear in the index to allow access to information.

Furthermore, indexing serves a secondary purpose of organizing information. As discussed above, the feminist historical paradigm applied to music history asks both what it means to be "musical" and what it means to have made a contribution to music history. The textbook that seeks to be adaptable to a broad-based music history class therefore ought to include the contributions of patrons and dedicatees, for example, instead of simply focusing on "great composers," and its index ought to include such categories to allow for this change in focus.

Reflections on the Process of Curricular Reform

In the final phase of feminist scholarship, McIntosh envisions a "Reconstructed, Redefined and Transformed" history which includes us all. Such history involves not only a recovery but an active reinterpretation of the past. As historian Joan Scott puts it, "Women are both added to history and they occasion its rewriting; they provide something extra and they are necessary for completion, they are superfluous and indispensable."31 In other words, the feminist endeavor changes the terms of the discussion, asking new questions of men's roles as well as of women's. A feminist revision of history—or of music history—requires a process of reform; through the various phases (however they are characterized), we deliberately "add knowledge about women to our self-conscious mental life."32 In the 1990s, we now know of the Concerto di Donne and the importance of their singing for the development of the virtuosic madrigal, and we are familiar with the evocative and associative poetic-musical language of Hildegard of Bingen. Such exempla of historical women have themselves enriched our history of the past.

But a feminist revision also demands a process of transformation;33 history provides "a way of supplying the vision of a changed future, even if it is described in fantasies about the past."34 Though they may propose different schemes for understanding the evolution of a discipline, feminist phase theorists—and their many feminist sisters and brothers—consistently believe that women's history must be "integrated" and not just "included"—"we do not simply add the idea that the world is round to the idea that the world is flat."35

Much of the material for this kind of study is already available. Scholarship—by feminists, by antifeminists, by people afraid to be thought of as feminists and by people who avoid thinking about feminism as an issue—has been good to us in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Archival work and literary studies, analytical studies and biographical ones have turned up a rich field of material on a variety of perspectives. It is up to us to ask the inclusive questions that would put the stories both of men and of women into our music history classrooms.

1Two anthologies of music by women composers include multiple selections by medieval and Renaissance women: James R. Briscoe, ed., Historical Anthology of Music by Women (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987); and Martha Furman Schleifer and Sylvia Glickman, eds., Women Composers: Music Through the Ages, Vol. 1: Composers Born Before 1599 (New York: G.K.Hall, 1996). The first women-in-music textbook was issued in 1991: Karin Pendle, ed., Women and Music: A History (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991). Carol Neuls-Bates' collection of source readings has proven popular enough for a second edition: Carol Neuls-Bates, Women in Music: An Anthology of Source Readings from the Middle Ages to the Present, Rev. ed. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1996). The scholarly publications on women have increased extensively in number over the last few years. One of the best access points to that literature is Margaret D. Ericson, Women and Music: A Selective Annotated Bibliography on Women and Gender Issues in Music, 1987-1992 (New York: G.K. Hall & Co., 1996). Significant reviews of feminist scholarship and feminist pedagogy in these pages include Jane M. Bowers, "Feminist Scholarship and the Field of Musicology: I," College Music Symposium 29 (1989): 81-92 and Idem, "Feminist Scholarship and the Field of Musicology: II," College Music Symposium 30 (1990): 1-13; see also Barbara Coeyman, "Applications of Feminist Pedagogy to the College Music Major Curriculum: An Introduction to the Issues," College Music Symposium 36 (1996): 73-90.

2The discussion that follows focuses on women, ignoring religious and ethnic minorities and skirting class issues. An extensive study of Renaissance minorities and their musical roles and experiences is long overdue.

3Claude Palisca, Norton Anthology of Western Music, Vol. I: Ancient to Baroque, 3rd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1996), 35.

4Howard Mayer Brown, Music in the Renaissance, Prentice Hall History of Music Series (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976), xiii.

5Brown, Music in the Renaissance, xiii.

6Florence Howe, "Feminist Scholarship: The Extent of the Revolution," 1981-82; rpt in Myths of Coeducation: Selected Essays, 1964-1983 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 282-3.

7Peggy McIntosh, "Interactive Phases of Curricular Re-Vision," in Towards a Balanced Curriculum, eds. Bonnie Spanier, et. al. (Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1984): 25-34, especially 26.

8Beatrice Pescerelli, ed., I Madrigali di Maddalena Casulana (Florence: Olschki, 1979).

9Alfred Einstein, The Italian Madrigal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1949), 510 and 529; in both contexts he mentions that Casulana was a composer but only discusses her role as dedicatee and as an editor of Antonio Molino's works: she "collects a number of her friend's madrigals . . ." (Einstein, 529).

10Howard Mayer Brown, "Women Singers and Women's Songs in Fifteenth-Century Italy," in Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950, ed. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 62-89; see especially p. 64. Note that recent investigations of women's monastic communities by Craig Monson and Robert Kendrick have revealed aspects of women's musical training in the church. See Craig A. Monson, Disembodied Voices: Music and Culture in an Early Modern Italian Convent (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); see also Robert Kendrick, "Genres, Generations and Gender: Nuns' Music in Early Modern Milan, c. 1550-1706," Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1993; idem "The Traditions of Milanese Convent Music and the Sacred Dialogues of Chiara Margarita Cozzolani," in The Crannied Wall: Women, Religion, and the Arts in Early Modern Europe, ed. Craig Monson (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992), 211-33.

11Jane Bowers and Judith Tick, Introduction to Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 4.

12J. Michele Edwards, "Women in Music to ca. 1450" and Karin Pendle, "Women in Music, ca. 1450-1600," in Women and Music: A History, ed. Karin Pendle (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991), 8-28 and 31-53.

13On women's experience, see Pendle, 32; on women and marriage see Pendle, 33.

14Pendle, 35.

15Pendle, 36.

16Pendle, 46.

17McIntosh, "Interactive Phases," 26-27.

18Paula Higgins, "Parisian Nobles, a Scottish Princess, and the Woman's Voice in Late Medieval Song," Early Music History 10 (1991): 145-200.

19Higgins, 153.

20Anthony Newcomb, "Courtesans, Muses, or Musicians? Professional Women Musicians in Sixteenth-Century Italy," in Women Making Music, op. cit., 90-115.

21Newcomb, 93 and 101.

22Newcomb, 109.

23Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, "Placing Women's History in History," New Left Review, No. 133 (May-June 1982): 5-29; see especially p. 6.

24McIntosh, "Interactive Phases," 33.

25The unnamed widow of Attaingnant served as a printer; see Brown, 188. She is listed under "miscellaneous" in our survey.

26Diane Jezic and Daniel Binder, "A Survey of College Music Textbooks: Benign Neglect of Women Composers?" in The Musical Woman: An International Perspective: Volume II: 1984-85, ed. Judith Lang Zaimont (New York: Greenwood Press, 1987), 445-469. Their focus on women composers to the exclusion of women's other roles would count as "phase two" scholarship in McIntosh's schema, but their contribution was among the first to point out a significant gap in our educational model.

27Ibid., 466 and 467-8.

28If a given reference indicates that the wedding composition mentioned the woman by name, it was also included under "women as dedicatees."

29Reese, Music in the Middle Ages and Reese, Music in the Renaissance both list individual women in the index; other texts are neither as consistent nor as thorough. Even Reese omits general categories such as "patron" or "performers" that would allow tracking of women's participation in music as a general social phenomenon.

30Gallo, 50.

31Scott, "Women's History," 49.

32Catharine R. Stimpson, "Women as Knowers," Ch. 2 in Feminist Visions: Towards a Transformation of the Liberal Arts Curriculum, ed. Diane L. Fowlkes and Charlotte S. McClure (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1984), 17.

33Diane Fowlkes and Charlotte McClure have evoked an action-oriented schema to describe curricular reform: first there is a critique of the present body of knowledge, next an enrichment of the present body of knowledge with the new scholarhsip on women; finally there is a transformation of the present body of knowledge. See Diane L. Fowlkes and Charlotte S. McClure, "The Genesis of Feminist Visions for Transforming the Liberal Arts Curriculum," Ch. 1 in Feminist Visions: Towards a Transformation of the Liberal Arts Curriculum, ed. Diane L. Fowlkes and Charlotte S. McClure (University, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1984), 5-6.

34Linda Gordon, "What Should Women's Historians Do: Politics, Social Theory, and Women's History," Marxist Perspectives 1 no. 3 (Fall 1978), 129.

35Peggy McIntosh and Elizabeth Kamarch Minnich, "Varieties of Women's Studies," Women's Studies International Forum 7 (1984): 139-148.