Introduction

CMP

Retrospect

Today

Tools

Blueprint

Next

References

The notion of needing to reform music education has probably been around since our profession's inception. In the past fifty years, we have seen remarkable improvements in many areas of music education. It is probably safe to say that, on the whole over this period of time, the quality of public school music programs has never been better.

However, the curricular model that prevails in music teacher education (understandably driven as much by institutional rigidities as pedagogical tradition) remains largely unchanged. A review of undergraduate music education programs will reveal an almost identical litany of required courses, practically no room for electives, and universal focus on producing specialists in general music, and band, choral, and string pedagogy. At the same time, music teacher education programs are being expected to incorporate emerging developments and sociological issues that impinge on our field, often without curricular space to add courses or funds for hiring the specialists who can teach them. Some of these changes, like music technology, alternative learning assessment, adjustment to diverse student learning styles, and understanding of different racial and ethnic populations almost run counter to prevailing teaching methods and ensemble traditions that have served the profession so well for decades.

At the same time, the never-ending struggle to justify music programs in public schools remains. Unlike the past, where often the only demonstrable evidence of a school music program's accountability to administrators and community leaders was winning performance competitions, the push toward establishing music as a curricular subject in schools around the country has provided another opportunity to strengthen our profession's position in the US. Through such initiatives as Goals 2000, The National Arts Education Standards, and MENC's Housewright Declaration and Opportunity-to-Learn Standards for Music Instruction, public school music programs can be designed to function on equal footing with traditionally accepted, academic subjects.

However, to accomplish this task, school music programs need to be inclusive of the student population. While general music programs have, historically, addressed schools' entire student bodies, performance ensemble programs have not. In the upper grades, a distinct minority of students participate in or have access to music instruction. Much of this problem rests with the nature of the ensembles, the manageability of student numbers, and instructional time. Also, in order to maintain the quality of musical performance that is recognized not only by the ensemble director, but students, administrators, and parents, some means of selecting and excluding student participants is necessary.

This tradition undermines the position of music as a curricular subject in the public schools. Virtually all academic courses function from grades K-12 and are either mandatory for all students, meet graduation requirements, or satisfy admissions requirements of collegiate institutions. While Advanced Placement and upper level courses in science, mathematics, and foreign languages are selective, students do have the opportunity to qualify for enrollment through a series of prerequisite subjects. Moreover, completion of these courses can usually be tied to formal fields of collegiate study, whereas for all but a small minority of aspiring music majors, the high school performing ensemble usually serves as an enrichment activity. Even for the prospective collegiate music major, there is often little opportunity to take pre-college musicianship courses (usually in music theory and music history), either because the ensemble directors do not have the time to teach them or there are not enough student enrollments.

If music is to become a curricular subject that is to be perceived by policy makers, school boards, and parents as integral to a child's education, then it must be available for study through all of the school grades. It must also be able to address the needs and abilities of learners in a more comprehensive way than it currently does, if it is to be inclusive of this nation's student body. To accomplish this task, music education majors will need to know much more than common practice music theory, western European music, ensemble conducting, Orff-Schulwerk/Kodaly/Dalcroze, and how to perform skillfully on an acoustical instrument, (let alone generate lesson plans on non-western music or be able to print out a score in Finale). In fact, the vast amount of musical and pedagogical knowledge to which today's music educator needs to have access is overwhelming. The kind of music program and teaching in Mason City, Iowa that is highly effective there would not work in East Los Angeles. Teaching in a school populated predominantly by students of African-American descent may require completely different instructional strategies and course content than in another school heavily populated by Hispanic and Asian students. Teaching students with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) can be quite different from working with students who come from single-parent families. A music educator who is required to instruct general music, beginning band, and choir in a small, rural school district will need a more diverse battery of teaching skills than a band director resident full-time in a well-financed suburban high school.

Given this scenario, it is little wonder that music teacher education programs have not undergone dramatic changes. To even speculate on curricular reform that would address these issues in the prevailing degree template used for most music teacher education programs is mind-numbing. What is clear, however, is that tomorrow's music educator will have to be versatile, adaptable, open to new ideas, creative, resourceful, and constantly learning - not just in the specialty or musical genre of one's preference, but in all of the areas that need to be understood for effective music teaching to take place in the immediate school context.

This prospect challenges long-held beliefs about what the music educator needs to know and be able to do as musician and teacher, because there is no way to address the kinds of concerns raised here without eliminating or de-emphasizing some of the musical knowledge and skill cherished by our profession.

Fortunately, the music education field has in its history some initiatives that did address curricular reform, thus providing the less daunting prospect of exploring uncharted territory. However, we have to go back several decades to reacquaint ourselves with them.

The 1960s were an exciting time in college music curriculum experimentation. Projects during this decade included the Young Composers Project, the Contemporary Music Project, the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Program, the Yale Seminar on Music Education, the Tanglewood Symposium and the Juilliard Repertory Project (Mark, 1996). The Contemporary Music Project for Creativity in Music Education (CMP) was probably the most intensive, well-funded and effective curricular project in college music education which focused on comprehensive musicianship in undergraduate college music training.

The Contemporary Music Project grew out of the Young Composers Project, which began in 1958 with a $200,000 grant from the Ford Foundation, to place young composers into public schools. As the Young Composers Project developed, it became clear that teachers in public schools needed better training toward the understanding and acceptance of contemporary music. Many of the conflicts between the music teacher and the professional composer were a result of "the outmoded training that the majority of music teachers received" (Contemporary Music Project, 1971, p.29). In 1963, the Ford Foundation gave $1,380,000 in order to establish the Contemporary Music Project, which was administered by MENC. CMP continued to place composers in public schools, but also used the funding to host seminars and workshops for music educators and college professors. It piloted projects in elementary and secondary schools in order to bring contemporary music to the classrooms and to realize musical talent through the activities of creative experiences, improvisation, and composition (Contemporary Music Project, 1971).

Over the years of the project's existence, the policy Committee was made up of a variety of well-known composers, educational leaders, and professors of music theory, musicology, and music education in a true spirit of collaboration and cooperation amongst the facets of college music education. The main emphasis of the CMP early on was to bring about more favorable conditions for the "creation, study, and performance of contemporary music" (Contemporary Music Project, 1965, p.3) for college music students and public school children. Music teacher education programs were specifically targeted (in addition to basic musicianship courses) to cultivate lateral and cross-disciplinary thinking amongst their students and to create a better connection to contemporary music. These ideals could only be realized through an integrated and comprehensive collegiate music curriculum; a model that would require change in course structure and faculty attitudes about what is important to know in order to be an effective music educator in the classroom.

Specific needs outlined for music education curricula were as follows:

- to increase the emphasis on the creative aspect of music in the public schools;

- to create a solid foundation or environment in the music education profession for the acceptance, through understanding, of the contemporary music idiom;

- to reduce the compartmentalization which now exists between the profession of music composition and music education for the benefit of composers and music educators alike;

- to cultivate taste and discrimination on the part of music educators and students regarding the quality of contemporary music used in schools; and

- to discover, when possible, creative talent among students in schools.

(Contemporary Music Project, 1971, p. 32).

Between 1963 and 1965, 16 seminars and workshops were held at various colleges and universities and 6 pilot projects at public schools and/or universities. Probably the most influential conference was the Seminar on Comprehensive Musicianship held at Northwestern University in 1965. Groups of music educators, theorists, composers, historians and performers were summoned "to examine the content and orientation of those required college music courses . . . generally called musicianship training" (Contemporary Music Project, 1965, p. 3). They were also prepared to look at the total curriculum as it related to preparation of public school music teachers. The recommendations from this conference helped to formulate the first definition of comprehensive musicianship and put into motion the change for college music courses.

Concerns that were brought to the Northwestern seminar included the need to study music traditions outside of the 18th and 19th century. It was suggested that the grammar and syntax of the music from the present time be studied and then related back to its sources from former times. There was a feeling that music literature masterpieces studied in history and musicianship were too disparate from the materials used for teaching/performing. There was strong sentiment that prospective teachers needed to find means for developing their own creative potential and apply this to creative techniques for teaching music to young children.

Specific recommendations were made in the following areas:

- "There was general agreement that training in the practice of composition is an essential element of training for comprehensive musicianship, and that it should be part of the required subject-matter in college schools of music" (Contemporary Music Project, 1965, g. 11). The typical part-writing courses would not suffice, rather creative composition was needed. Pertaining to music teacher preparation in particular: [Composition] should equip future school music teachers and conductors to understand the compositional principles underlying any work, to impart these principles to their students, and to apply them in teaching music theory, performance, or history, and above all in their own performance" (p. 11).

- Aural skills leads to analytical insight which is crucial for aesthetic understanding and appreciation. This connection between aural skills and aesthetic understanding must be made. Repertoire for aural skills classes should be representative of all periods and styles (jazz, folk, electronic, student-composed) and analysis should occur in all courses: "the elementary or secondary classroom, the studio, the music literature class, and the rehearsal room" (Contemporary Music Project, 1965, p. 16).

- These courses should cover a wide range of repertoire (including non-Western and 20th-Century), however exploration of certain composers, styles, genres or periods should be in-depth with considerable focus on context. All music courses should be interrelated: ". . . we wish to stress that students trained under this proposed program of comprehensive musicianship should be capable of teaching well both theoretical and historical studies, and of relating these studies to performance" (Contemporary Music Project, 1965, p. 20).

It was also argued during this seminar that there was a great need for a philosophy of music education in the music education profession. "Even though music educators have in recent years grown more receptive to philosophy, there exists no comprehensive philosophy of music education" (Leonhard, 1965, p. 43). This point may be the one which has indeed come to fruition in music education thanks largely to the writings of Reimer (1989) and our current healthy state of philosophical debate in music education philosophy (e.g. Elliott, 1991; Reimer, 1991).

The ideas set forth from the Northwestern Seminar were tested from 1966 to 1968 through 6 regional Institutes for Music in Contemporary Education (IMCE). Thirty-two colleges and universities participated by developing and teaching experimental courses. The teachers who taught IMCE courses at each institution came from a variety of disciplines within music theory, history, literature, performance, and music education. Though the format, content and procedures of the ICME courses varied, their goal was to teach integrated courses applying the comprehensive musicianship approach; that is involving the three components of composition, performance, and analysis. They also integrated ideas from the 1963 Yale Seminar and changed thinking from past reliance on behaviorist techniques to more recent ideas in education such as from Bruner and Gestalt psychologists (Willoughby, 1971).

CMP for Music Educators - in retrospect

It seems that after the 1965 seminar on comprehensive musicianship, music education took a back seat in the college music curriculum reform effort. While music education, as a group or field of study, was specifically targeted at the beginning of CMP and in the Northwestern Seminar, it lost its focal point in follow-up projects. Basic musicianship courses at the undergraduate level became the focus for reform. The most interesting projects relevant to public school teaching, The Ithaca College and Interlochen Arts Academy projects (Benson, 1967), offered creative ideals for music educators, but were not followed through in the last publications of CMP (i.e., Willoughby, 1971). Reflections and speculations by those active as public school teachers during that time point to the rigidity of the performance ensemble goals and structure at the secondary public school level (Burton, 1990; McManus, 1990; Warner, 1990). "My greatest disappointment was my inability to influence most directors of large ensembles to touch base with creativity instruction. Tradition and status quo were clear winners in band and orchestra classes and were certainly easier for teachers" (McManus, 1990, p. 50).

The Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (MMCP), which also had a national presence for a few years during the late 1960s and early 1970s, contained some elements common to CMP, but was more focused on music teacher education (Thomas, 1970). Aspects of the MMCP approach were applied to secondary classroom music in Australia by Helen Stowasser during the late 1970s and 1980s and became an underpinning of her writings and curricular work in the states of Queensland and Western Australia. Leon Burton initiated the University of Hawaii Project, with its tenets grounded in comprehensive musicianship (Burton, 1990). MENC took up the reins and began efforts toward music education reform. However, the initial ideas behind true curriculum integration among all disciplines were lost.

One common weakness with these curricular efforts was the lack of formal evaluation of student learning. There were few replicable outcomes published on the effectiveness of these programs' information that might have inspired practitioners to consider redesigning their curricula (exceptions were studies by Gibbs, 1972, and Taylor and Urquhart, 1974). Another problem was the significant shift in priority that almost all of these projects took away from transmission of subject content and skill that had been the byword of most collegiate music programs, pointing instead toward processed-based education. The non-course content/skill mastery model that was implied by process-based learning ensured almost no alliances between those few music educators who saw its value, and all other music education specialists and members of the higher education musical community, for whom there never was perceived to be a need to change business as usual. In the meantime, the music education community seems to have lost the connection with the college teachers in the other disciplines. Our collegiate instrumental music education majors are shaped to be band and orchestra directors, but not much more.

Could our college music education faculty stand by the goals put forth to college teachers 30 years ago (bullets above)? Can we bridge the seeming disparate gap between the music disciplines once again? The time seems right with initiatives such as the National Standards in Music Education (MENC, 1994). Evidence of interest in this approach toward curricular change can also be found outside of music such as through the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching's current Pew Scholar Program or the FIPSE programs special grant competition, announced during the Spring of 1998.

At the local level, institutes like the University of Northern Iowa's Center for the Enhancement of Teaching are supporting grants for faculty in which institutional resources are being directed toward assisting them to integrate curricular elements within existing course work and between courses of a given discipline or across disciplines. Duquesne University advertised a faculty position that involved teaching across the common core of undergraduate musicianship subjects.

There has also been activity involving curricular reform, particularly by a few prominent colleges in major universities and with at-risk students in the public schools. Probably, the greatest impetus for curricular reform has been the problems facing urban schools and public schools with ethnically diverse student populations. The didactic approach to teaching was generally not working for many of these learners, precipitating the need to find alternative ways to engage students in learning. Today, it is probably safe to suggest that many of our students, regardless of cultural, racial, ethnic or socio-economic background, inherently need us to possess a variety of approaches to music learning.

Since the 1970s, there have been numerous education researchers and scholars who have been concerned about alternative modes of teaching and learning (not necessarily driven by communal need, as much as their realization that there must be other ways to learn than those which we have traditionally considered effective). Some researchers' work, (e.g., Howard Gardner or Theodore Sizer), provided support for different teaching/learning models. The North Central Regional Educational Laboratory listed at least sixteen curricular initiatives that were having impact at the national level (http://www.ncrel.org). Among them were: the Charter Schools Movement (as of September, 1999, 31 states and the District of Columbia had 1,700 charter schools in operation, serving 350,000 students) (http://www.edreform.com); the Accelerated Schools Project (originally started by Henry Levin at Stanford University, now with involvement of over 1000 schools in 41 states) (http://www.stanford.edu/group/ASP/); the ATLAS Communities (an initiative by James Comer, Howard Gardner, Theodore Sizer, and Janet Whitla, with a reported student participation rate nationally of 42,738) (http://www.edc.org/FSC/ATLAS/about/stats.html); the Coalition of Essential Schools (with over 1000+ schools involved) (http://www.essentialschools.org), and; the National Paideia Center (based out of University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill) (http://www.unc.edu/paideia/).

Some of these efforts hail from the early 1980s, suggesting they may have educational credibility. A common theme with almost all of them rests with the idea of learner-centered environments, in which students discover and construct meaning from their own experiences. They tend to be inclusive of the school population, in which all students have access to the same body of knowledge and learning experience. The students can also depend upon receiving individual attention, rather than being herded through group activities that may or may not address their respective learning interests. Teachers, students, parents, other community members, and school administrators work together to facilitate student learning. Gone is the notion of the teacher as purely deliverer of instructional services or working in isolation of other teachers and disciplines. Another theme that seems to surface among almost all of these initiatives is that curricular models and learning strategies have to be either adapted for local school contexts or constructed out of such environments. This is a significant departure from the practice of centrally designing a curriculum and then expecting it to be universally transmitted to all students in the same way. Such an approach has allowed for greater opportunity to address students' different learning styles, aptitudes, and abilities, as well as to provide access to information and educational experience that traditional curricula did not seem to address. Another common aspect is the criterion of accountability, particularly for student learning. This means that some form of examinations or other learning assessments are systematically applied, to determine the validity of a given project in a school.

Other initiatives also promoted interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary curricular approaches. In music, one of the first projects was Arts Propel, as a part of Howard Gardner's Harvard Project Zero (http://pzweb.harvard.edu/), in which arts students used portfolios and student self-assessment to foster immersion in arts studies and critical thinking skills. The Association for the Advancement of Arts Education (AAAE) identifies fourteen arts programs with interdisciplinary elements (including Project Zero, Arts-In-Basic Curriculum Project [ABC], Target 2000 Project in South Carolina, Comprehensive Arts Planning Program [CAPP] in Minnesota, and ventures supported by Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, and the National Endowment for the Arts) (http://www.aaae.org/models/models.html). Other smaller examples of arts-based interdisciplinary field implementations would be the Children's Design Collaborative (New Hampshire), where multidisciplinary, thematic units for elementary grade children are used, and the Giblyn Elementary School in Yonkers, New York (http://www.unc.edu/paideia/) that employs the seminar model and theme-based collaborations between classroom instructors, the school librarian, and the art and music teachers (including the use of composition as a tool for music learning). Finally, electronic technology figures in these initiatives, being used to foster student projects and enhance student learning.

While it is not always clear from project reports on the level of involvement and effectiveness of music programs in curricular efforts, it is certain that music's presence in school curricula would be integral to their educational missions.

A Review of some Tools for Curricular Reform

The traits and values common to most of the major curriculum reform initiatives in the United States can be identified as follows:

- they are student-oriented, thereby are better able to address different learning styles and cultural traits among students;

- they are inclusive of the student population, viewing their missions as providing equal access to information, knowledge, and learning experience for every student in the respective school;

- they involve not only the collaboration of participating teachers but the students, administrators, parents, and other members of the community;

- they view the teacher more as a facilitator rather than a dispenser of knowledge;

- they derive their reform credibility by adapting new curricular elements with socio-educational traits of a given school or constructing a new curriculum out of the qualities and resources of that institution;

- they are accountable for the effectiveness of their programs and are assessed accordingly;

- they design curricula to function in interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary modes, and;

- they use electronic technology to enhance the learning experiences of their students.

Toward a New Technology (Blueprint) for Music Teacher Education

If we look at technology, not just as computers and synthesizers (which at best represent sub-sets of the term) but as tools, techniques, or devices that enable us to do our work more easily and productively, then we can employ one of its other resources, a plan or blueprint, to help us organize a new technology for music teacher education.

We may be able to use the common values and traits of contemporary and previous curricular reform to define the framework for this blueprint. However, in its design, the active involvement of all music educators is paramount for it to generate meaning and value to our profession. To provoke discussion and debate, the initial steps toward its design can be proposed here, but it remains to the reader of this document to contribute toward its realization.

The new music teacher education program will want to consider how the common values and traits of curricular reform will be addressed in the collegiate setting.

- Using Student Centered Learning to Readjust the Curricular Agenda for Music Education

On individual bases, many music practitioners have adopted different strategies to accommodate student-oriented learning, including those who run large ensemble programs or teach multiple sections of general music classes per week. Much of the thrust toward authentic assessment with student portfolios, student self-assessment, and formative assessment attest to systematic efforts by music educators to encourage students to be invested in their own learning. However, other tools are also available to assist in individualizing student learning, notably those available through electronic technology.

Students do not always have to be present in the same class, at the same time, performing the same tasks in the presence of the same teacher. The computer can allow them to engage in learning tasks outside the formal classroom meeting (called asynchronous learning). Some of these tasks, though musical in content, might be overseen by the librarian, teacher in another discipline (particularly if assignments complement concepts or skills that that teacher wants addressed), technology specialist in a computer lab, teacher aide, or even parent volunteer. There are now numerous music learning tools for young learners, ranging from CD-ROM programs that encourage students to experience music through composition and song writing (e.g., Making Music; Rap, Rock, and Roll) to cultivating aural association and sensitivity (e.g., Adventures in Musicland, Music Ace). Critical to this point is that the music educator may be able to personalize learning for the student, without having to micromanage every step of his or her learning agenda.

- Learning Adaptive Strategies to Work with All Learners

The growing diversity of American culture, the challenges of teaching students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, and the practical problems of keeping students with behavioral and handicapped disorders engaged in active learning must be addressed, particularly if an agenda of inclusiveness for all students in music learning is to be upheld.

The need for the study of more diverse music traditions, first articulated by the CMP initiatives, is more important today than ever. Historically, the general music, band, orchestra, and choral program, with its roots in European musical tradition, reflected the cultural heritage of this country, at least to the end of World War II. However, this is no longer so, particularly in urban areas, the South, and on both coasts. A review of U.S. Census estimates through 1999 (http://www.census.gov/population/estimates/nation/intfile3-1.txt) continues to show a decline in the white (non-Hispanic) population, while other ethnic and racial groups increase. The vast proportion of production and consumption of music in the US is grounded in rap, rock, country and western, rhythm and blues, pop, and gospel genres. Many of their composers, arrangers, and performers are self-taught, and while the best of them may be professionally trained (particularly for public performance), the need to be musically sophisticated technically and musically literate are not necessarily priorities. The Recording Industry Association of America's sales surveys from 1988 through 1998 indicate a yearly mean of 3.3% (jazz has shown a decline from a high of 4.9% in 1989 to 1.9% in 1998). This is against an increase in national sales from $6,579,400 in 1989 to $13,723, 500 in 1998 (http://www.riaa.com/stats/stats.htm). These statistics suggest that the music we are teaching and the tools that we are demanding music students to cultivate reflect a minuscule percentage of musical interest among American consumers.

- Designing Curricular Collaboration Models in the Collegiate Setting

Change must take place at three levels within our collegiate settings: within our own music education programs, across the music department or school, and, across our campuses. This means that, over a period of time, individual faculty within the music education divisions, then with colleagues in their faculty units of music theory, music history, and applied study, and finally with the faculty of the whole, would review their work and collaborate together to revise the music curriculum.

Questions we must begin to ask within our own programs should include: What are we teaching in our music education methods classes? How does what we teach fit into recent reform efforts such as the National Standards? How can we integrate composition and comprehensive musicianship (perform, describe, create) skills into teaching methods through the teacher education courses? Are we giving our methods students the tools to teach (or at least find) a wide variety of repertoire for public school students? Recall the musical initiatives from CMP and imagine teaching music education students to teach composition. Imagine teaching music methods to cultivate music analysis skills through performance (be it a performance of a 3rd-grade Orff ensemble or a top notch high school orchestra).

We might test ideas through cooperative student teaching sites. Other opportunities for experimentation may come in schools that have no music program and would welcome our help. Regardless of the site and the type of outreach, ideas that work must be evaluated, documented as such, and then shared with others through workshops and in-service programs. Unless active teachers are able to see exactly how a new idea works, they will not be amenable to change their daily teaching routines, much less accept a different philosophy for teaching their students.

To most college methods teachers, comprehensive musicianship strategies probably seem above and beyond the practical demands of our usual methods course contents where we are concerned with simply teaching our students how to manage a classroom, to move a baton in the correct manner, to learn to listen and correct musical mistakes, and to recruit beginning trombone players in the fall recruitment days! In typically crowded course loads for undergraduate music education majors, the idea of adding to methods requirements is simply not practical. This is where the next level of collaboration may work more to our benefit.

At the second level, we might begin by talking to our other colleagues within the music school. We must find the points of common interest between the music education faculty and the others. What does a comprehensive ensemble conductor do? Can our ensemble conductors model this? Perhaps the repertoire studied in the private studio can become the focus for an aural skills and music history class as well as a music education methods class. Maybe the repertoire being studied in the choral methods course can be brought to the aural skills class for discussion and analysis for teachers. Do our composition faculty colleagues realize that there are National Standards for music education which include music composition? The dialogue and sharing of expertise could be quite rich with some simple conversation and education about our music education needs from the composers' standpoints. The music education faculty must take the lead on this and begin the dialogue in their respective schools.

Finally, we need to reach across campus to the experts who are willing to share and help our music education students learn. Collaboration amongst all education faculty and departments would facilitate creative initiatives and ideas for inter-disciplinary education projects. Our music education students should be involved with, for instance, the history education and special education students in whatever ways possible. Faculty with expertise in child development, urban teaching, special education, and others with complementary interests, may be interested in forming a dialogue between the music education students and faculty within their own departments. Technological communication (such as e-mail and listserves) could make possible rich dialogues amongst students and faculty without the need for extra class time.

- Equipping Music Education Majors to Work in Different Educational Contexts

We need to guide our students in reaching out to opportunities outside of our insular college communities. Several opportunities exist for non-traditional music teaching. For example, the New Horizon's Band movement, begun by Roy Ernst at the Eastman School of music, provides band lessons to retired adults and is growing rapidly across the country. Music education programs are beginning to take advantage of this initiative by partnering students with adult beginners. Schools close to urban settings face creative challenges to try to connect with populations who do not have the desire (nor resources) to learn traditional band music. We must be up to facing these challenges and creatively finding solutions for the alternative musical situations in our neighborhoods.

- Identifying Tools for Assessing Music Learning

One of the virtues of accountability is that it forces both teachers and students to look back upon what they have learned against the activities and knowledge gathering in which they have been engaged. Besides the written and musical performance exams that are in common use, the portfolio, self-evaluation, and formative evaluation can be of value in determining student learning. However, when and what tests are used has to do with the kind of information that the teacher and student wish to gather. The issues here are to match testing with learning objectives and to generate information that will be useful to the learner, not just testing as a means of ranking the student against others or some pre-set criteria (unless the learner understands the value of meaning them). Decisions on assessment can only be determined at the local level for what is appropriate to facilitate learning.

- Using Music Technology for Music Teacher Education

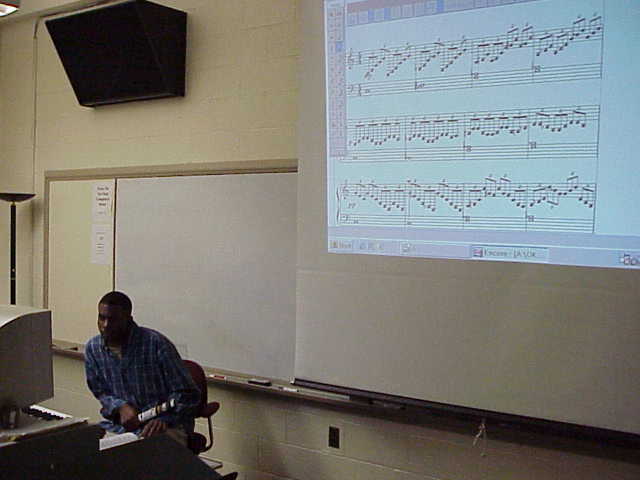

Probably one of the most effective tools for curriculum reform has been music technology. Like other strategies for learning that recognize few students will remember a concept, retain a fact, or acquire a skill with understanding by mere presentation or repeated drill, the computer and related music technologies are providing evidence of another avenue for facilitating music learning. These range from providing access to instructional experience through distance education, using distance technology to enhance instruction and learning on-campus. Computer-based music laboratories can exercise students' aural and music reading skills, enable them to use CD-ROM programs that combine elements of music history, music theory, style analysis, and repertoire on a range of musical topics, and for generating compositions, printed scores, or marching band field configurations. It is the interaction with these programs, more and more of which are attractive and sophisticated, that can engage the student in productive music learning.

One of the ways in which music learning can be facilitated is through composition. Long an instructional vehicle in Great Britain and other Commonwealth countries, composition or music writing has enabled students to acquire substantive musical knowledge. This strategy was a hallmark of the MMCP initiative, and is a priority in the National Arts Education Standards. It is, of course, a weak link in American music teacher education, although there is evidence that this status is changing.

Music technology is well-set to foster the creative aspect of music learning. MIDI workstations using sequencing programs can enable music students with no piano or music reading skills to generate original (for them) musical works that, along with computer and keyboard program functions, can sound well-performed and constructed in virtually any musical style. This opportunity to engage all students with the creative process of music-making could address the countervailing effect of the exclusive ensemble performance program. For the student who did not benefit from a general music class that formatively cultivated musicianship skills or who could not relate to the school band program (if one was available), using music technology could provide a gateway for music learning. The following two movie clips show examples of students composing using technology. This is one of the first attempts for them to compose a piece of music using technology and standard musical notion. In the interview, they are asked to identify the style and type of music composition they are generating.

|

|

The same computer on which a student uses email or a word processor could easily be set up with an inexpensive sound controller, sound module, sequencer, and headphones for a few hundred dollars. This offers a financially more flexible and convincing alternative to the purchase of a double bass or trumpet, and could be installed in any classroom or computer lab. It could also allow the user to work on musical tasks independently of a scheduled group setting. Conversely, music labs can also be designed for group instruction and individual assignments that the teacher can monitor by headphones from a master console, thus providing opportunity for group and individualized instruction. This process provides opportunity to address different students' learning styles, as well as for students with different musical aptitudes to progress through their study in time frames that do not overwhelm or disaffect them.

Nothing presented in this article is intended to deride or denigrate the work of our colleagues in either music teacher education or public school teaching. With all of the problems and challenges facing music educators today, it remains a matter of fact that American music education is the best in the world. To suggest that the band/orchestra/choral tradition is passé is to be foolishly ignorant. Music is - music-, and these venerable avenues for cultivating music knowledge and value for music remain most important. However, we do need to involve more of our students in learning music, and we have the curricular precedence and increasing battery of tools to accomplish this objective. The time has come to work collectively toward designing a curriculum in the music teacher education program that provides as good a model for teaching all school students as we have for teaching some of the students. The forum is here and now for starting this process through the potentially rich dialogue between colleagues in the College Music Society and among the greater higher education community.

Benson, W. (1967). Creative projects in musicianship: A report of pilot projects sponsored by the Contemporary Music Project at Ithaca College and Interlochen Arts Academy. CMP 4. Washington, DC: MENC.

Burton, L. (1990). Comprehensive musicianship: The Hawaii music curriculum project. The Quarterly, 1 (3), 67-76.

Contemporary Music Project (1965). Comprehensive Musicianship: A report of the Seminar sponsored by the Contemporary Music Project at Northwestern University, April, 1965. CMP 2. Washington, DC: MENC.

Contemporary Music Project (1966). Experiments in musical creativity: A report of pilot projects sponsored by the Contemporary Music Project in Baltimore, San Diego, and Farmingdale. CMP 3. Washington, DC: MENC.

Contemporary Music Project, (1971). Comprehensive musicianship: an anthology of evolving thought. CMP 5. Washington, DC: MENC.

Elliott, D. J. (1991). Music education as aesthetic education: A critical issues inquiry. The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, II (3), 48-66.

Gibbs, Robert. A. (1972). Effects of the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Program on the musical achievement and attitude of Jefferson County, Colorado, public school students. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Colorado.

Leonhard, C. (1965). The philosophy of music education--present and future. In Comprehensive Musicianship: A report of the Seminar sponsored by the Contemporary Music Project at Northwestern University, April, 1965. CMP 2, (pp. 42-49). Washington, DC: MENC.

Mark, M. L. (1996). Contemporary music education. (3rd ed.). New York : Schirmer Books.

McManus, J. C. (1990). "Rats in the Attic" and other musical explorations. The Quarterly, 1 (3), 51-57.

Music Educators National Conference (1994). The school music program: A new vision. The K-12 National Standards, PreK Standards, and what they mean to music educators. Reston, VA: MENC.

Reimer, B. (1989). A philosophy of music education (2nd ed.).

Reimer, B. (1991). Reimer responds to Elliott. The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, II (3), 67-75.

Taylor, J. A. & Urquhardt, D. M. (1974). Florida State University: An experimental approach to comprehensive musicianship for freshman music majors. College Music Symposium, 14 (Fall), 76-88.

Thomas, R. B. (1970). Manhattanville Music Curriculum Program: Final Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Education, Bureau of Research. ERIC document ED 045 865.

Warner, R. W. (1990). CM reflections of a band director, The Quarterly, 1 (3), 45-50.

Willoughby, D. (1971). Comprehensive musicianship and undergraduate music curricula. CMP 6. Washington, DC: MENC.