I

Alas, it is one thing to envision in a creative instant of inspiration and it is another to materialize one's vision by painstakingly connecting details until they fuse into a kind of organism.

Alas, suppose it becomes an organism . . . and possesses some of the spontaneity of a vision; it remains yet another thing to organize this form so that it becomes a comprehensible message "to whom it may concern."1

In this passage from his 1941 lecture on "Composition with Twelve Tones," Schoenberg rehearses one of the most pervasive ideas of his unique brand of musical aesthetics, history, and theory; namely, a totalizing view of musical creation in which the need for a coherent and unified whole should be potentially satisfied with the vision of a composition's first musical gesture. Central to these aesthetic principles of coherence and unity is the musico-theoretical concept of motive. For Schoenberg, the motive not only represents a concrete expression of the musical Idea but also lies at the origin of all processes of thematic transformation that he identified as the historical common denominator uniting his music making to that of his predecessors. Moreover, the communicative capacities of music are largely determined by the clarity with which motivic ideas are woven into the larger, formal fabric of a composition.

The concept of motive plays quite a different role in Schenker's late theory. From the period of Das Meisterwerk in der Musik onwards, Schenker considers motives in terms of voice-leading transformations of simpler underlying events. As a result, the paradigm of hierarchical structure that Schenker advances in Free Composition downplays the significance of motives. This is made forcefully clear by the following passage: ". . . music finds no coherence in a 'motive' in the usual sense. Thus, I reject those definitions of form which take the motive as their starting point and emphasize manipulation of the motive by means of repetition, variation, extension, fragmentation, or dissolution."2 The correspondence between "'motive' in the usual sense" and the Schoenbergian motive and between "manipulation of the motive" and "developing variation" seems uncanny. Schenker's and Schoenberg's conceptions of musical coherence appear then to be separated by a seemingly unbridgeable conceptual gulf.3

In this paper I examine issues concerning motivic coherence in these towering figures of twentieth-century tonal theory. Particularly, I stress the pedagogical need for broader, more comprehensive analyses of motivic content and also offer an account of the difficulties and notational revisions necessary to carry this out. I do this not by attempting to resolve the dissonance existing between competing and ultimately incommensurable theoretical models, but rather by demonstrating the insufficiency of single analytical strategies to provide a comprehensive reading of motivic relations. It is within the conflict between opposing paradigms that I believe the possibility of richer analytical readings exists. My attitude, in short, is shamelessly pragmatic and even opportunistic.

I begin by presenting a close reading, after Richard Cohn, of the ontological and epistemological assumptions of the Schenkerian concept of motivic parallelism.4 That is, I survey Cohn's careful analysis of the nature of motives in late Schenker, his outline of the epistemological premises on which these motives are founded, and the conflicts he identifies between theory and analytical practice in Schenker and Schenkerians. I then propose two types of motivic parallelisms (structural and free) according to their conformance, or lack thereof, to structural considerations. The admission of motive forms which compromise Schenkerian structural considerations, we shall see, opens an interpretive window that offers a broader view of motivic relations as pure entropy. This view echoes Schoenberg's conception of motive as a depository of latent musical content. The dialectic resulting from this self-contained, dormant potential and its realization through transformations that do not subscribe to Schenkerian structural tenets must be carefully examined, and its epistemic domain clearly delineated. It is in this spirit that Schoenbergian notions of motive are utilized in this paper. A final type of motive, the referential motive, is closer to Schoenberg's conception, but in the end emerges as a complement to the first two types. A more abstract notion defining motive as sonority or voice-leading event, the referential motive incorporates musical parameters that are not explicitly available through motivic parallelisms or Schoenbergian motives.5 I conclude with a practical application of the theoretical issues discussed in the first part of the article by presenting an analysis that brings together voice-leading concerns with a mapping of various motivic networks in the "March in D" from the Notebook of Anna Magdalena.

II

Ironically, whereas Schoenberg's thoughts on musical coherence exhibit a good degree of consistency across his writings, Schenker's search for the source of unity in tonal music underwent substantial changes. Early in his career Schenker gave the motive considerably greater emphasis than in his later works. The motive, he explains in Harmonielehre, allows music to become an autonomous art by liberating it from the extrinsic associations with patterns from nature upon which other arts depend (shape in sculpture, for instance).6 Indeed, for Schenker motivic repetition constitutes the main agent in the creation of musical form.

At this early stage in Schenker's theory two musical parameters control the unity of a composition: the motive and the harmonic scale step. But whereas the motive is considered a concrete musical statement with specific temporal associations, the concept of scale step owes its nature to a more abstract conception of structural embedding (i.e., a harmony that encompasses other chords). From the time of Harmonielehre onwards, as Cohn notes, Schenker's theory can be seen as an ever-growing expansion via counterpoint of the span which a scale step governs (Cohn: 152). The ultimate consequence of this expansion can be seen in Free Composition, in which temporal associations take a back seat to the all-encompassing, spatial model of derivation from the Ursatz.

The synthetic impact of the Ursatz is totalizing: coherence derives at all times, and through all tonal events, which are, first and foremost, composings-out of underlying contrapuntal and harmonic structural units. Only after fulfilling this obligation can tonal events take on a motivic role, an added feature, so to speak, but one that is no longer seen as an essential source of compositional unity. Moreover, a motive must always be "capable of being proven by [a] voice-leading transformation," or composing-out, as Schenker asserts in Das Meisterwerk in der Musik (Cohn: 152). Any such transformation entails a hierarchical arrangement that makes it possible to ascertain the precise relationship between tones of different "rank." I will characterize this aspect of motives as derivational, a reflection of the synchronic nature of Schenker's late theoretical model. A composing-out, however, can be recognized as being motivic only on the basis of further iterations. Since these iterations occur in a temporal dimension, any discussion of a motivic parallelism must take into account its diachronic nature, that is, its associative relations, to invoke Cohn's expression.

A motivic parallelism entails a dynamic relationship between a pattern and its copies which grants the first pattern, usually standing closer to the foreground, a good measure of generational power. The greater number of examples of parallelism in the Schenkerian literature correspond to the pattern-copy type. But mustn't a motive originate from the Ursatz, not from another motive? (Cohn: 153-154.) It follows then that the concept of motivic parallelism raises basic questions about derivational (i.e., synchronic) and associative (i.e., diachronic) allegiances.

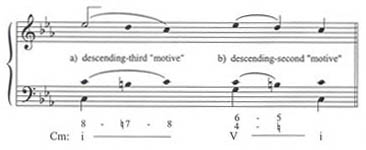

These tensions in the Schenkerian conception of motive are best observed in an illustration. Example 1, the well-known opening of the finale of Beethoven's Pathetique sonata, shows two events whose descants share pitch-class content and intervallic span but whose inner structural make-up is different (as shown in Example 2). We might claim that a parallelism exists between these events and label them the "descending-third motive," for instance, as in Example 2 at (a).7 But would this relationship be based on their mode of derivation from the Ursatz? If not, could the obligation of these events to their progenitor be relinquished in exchange for some kind of interrelational freedom? (Cohn: 158.) To provide an answer we must invoke Schenker's stern admonition:

[...] a simple element lies at the back of every foreground. The secret balance in music ultimately lies in the constant awareness of the transformational levels and the motion from foreground to background or the reverse. This awareness accompanies the composer constantly; without it, every foreground would degenerate into chaos.8

Example 1. Beethoven, Op. 13. III

Example 2. Structural description of apparent parallelism

According to this statement, we may issue "Schenkerian birth certificates" to the events of Example 2. The first one might reveal: that it is born out of the Ursatz, that it consists of the third-span  2-c2 filled in by the passing tone d2, and that the tonic scale step in C minor controls the motion.9 Proceeding to our next event the certificate would inform us that it is also born out of the Ursatz, that it consists of the prefix-type neighbor e2 descending to d2, the fifth of the dominant scale step, that d2 then gives way to c2, and that the span of the motion is a major second.10

2-c2 filled in by the passing tone d2, and that the tonic scale step in C minor controls the motion.9 Proceeding to our next event the certificate would inform us that it is also born out of the Ursatz, that it consists of the prefix-type neighbor e2 descending to d2, the fifth of the dominant scale step, that d2 then gives way to c2, and that the span of the motion is a major second.10

To propose the existence of a motivic connection between these two events would entail the abandonment of the derivational hierarchy and the adoption of supra-structural features such as contour and pitch-class identity as criteria to associate them. After all, the information contained in the Schenkerian notation of beams, noteheads, slurs, and stems is inseparable from an event's status as a derivational construct. And as shown in Example 2, these events possess structural characteristics that maintain a relation of identity, and not simply of similarity, with their derivational processes. In short, then, from an exacting Schenkerian position, derivation is how these events come into being.

An aspect of motivic parallelism seldom made explicit in analytical discourse is the consideration of what I call the stability conditions of a motive's members. A description of the contents of Example 2 as a "third motive" would, consequently, be incomplete. In Example 2a the motion occurs between stable points, while in Example 2b there is a gradual resolution of tension from the  2 to d2 and from there to c2. This transformation, or becoming, if you will, takes place along a temporal continuum and might be of greater interest for the analysis of the compositional trajectory of motives than the recognition of the parallelism itself. The transformation affects the listener's reaction to the expressive shifts motivated by the contrapuntal changes of the "same notes."

2 to d2 and from there to c2. This transformation, or becoming, if you will, takes place along a temporal continuum and might be of greater interest for the analysis of the compositional trajectory of motives than the recognition of the parallelism itself. The transformation affects the listener's reaction to the expressive shifts motivated by the contrapuntal changes of the "same notes."

Since, from a Schenkerian perspective, the transformation in Example 2 would be problematic, we must therefore concur with Cohn that the only motivic relationships available through the Schenkerian model are those between events that share the same structural derivation. This, however, would correspond to an identical twin relationship, an analytically unrewarding observation, save perhaps for those cases in which the same event acts at discrete structural levels but appears at different locations in a piece, in which case we would indulge in an awkward mixture of derivational and associative parameters. A typical case involves a foreground event that reappears at some level of the middleground. Schenkerians, in general, refer to such motivic relations as "cutting across voice-leading strata." This conceptual mixture implies neither a vertical nor a horizontal relation but rather a diagonal one, given the temporal differences involved. In analytical discourse, however, these relations are expressed dynamically and organically, following Schenker's metaphor of "seed and harvest" (Aussaat und Ernte). Under this description the diachronic dimension of a piece supersedes the synchronic aspect of Schenker's model; foreground events become a piece's motivic source. The connections that ensue more often than not ignore essential genetic traits (i.e., structural make-up) and form a network of relations that runs parallel (or simultaneously) to the hierarchical structure promoted by the Ursatz. And Schenkerians are usually given to interpret these associations as being valid. If to this we add, parenthetically, that a strictly hierarchical structure does not allow more than one unidirectional connection between two events, then we recognize that motivic parallelisms often blatantly break this stricture. All of which may lead us to agree with Cohn, who maintains that Schenkerian analytical practice, though often deaf to its own strictures, is all the better for it.

I would suggest then two criteria by which we may better determine the grounds of being (ontology) of motivic parallelisms. First, we must establish the nature of the structural relations between proposed motives; and second, we must consider the stability conditions among the constituent members of motives.

Under the first criterion I identify two types of motivic parallelism. The first type, termed structural parallelism, identifies relations between events whose structural descriptions (or Schenkerian birth certificates) are identical but occur at discrete levels (i.e., foreground, middleground, etc.).11 The second type, termed free parallelism, describes relations between motive forms that share surface appearances but whose structural descriptions may vary.

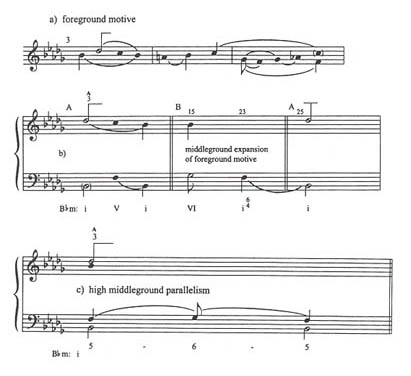

Example 3, the beginning of the vocal line from Schubert's daunting setting of "Ihr Bild" from Schwanengesang, illustrates the first type, a structural parallelism. Here a minute surface (at the foreground) neighboring motion from the beginning of the first strophe (Example 3a) reappears at a higher level (high middleground) where it is shown in Example 3b to become the controlling structural motion of the large-scale formal section B (a common feature of nineteenth-century small ternary pieces, for instance).12 At the high middleground level shown in 3b, however, the event does not fulfill the stability condition of the earlier statement of Example 3a, since here the neighbor  1 is rendered a consonance as the root of the submediant harmony. At a yet higher level of middleground, however, the stability condition expressed by the analysis of Example 3a reappears. As Example 3c indicates, the harmonic support of the neighbor tone

1 is rendered a consonance as the root of the submediant harmony. At a yet higher level of middleground, however, the stability condition expressed by the analysis of Example 3a reappears. As Example 3c indicates, the harmonic support of the neighbor tone  is subsumed under the larger controlling tonic scale step, becoming part of a 5-6-5 contrapuntal expansion of the tonic. Examples 3a and 3c hold a structural parallelism. It follows, then, that in establishing the existence of a parallelism one should "climb up" the structural ladder in order to determine whether or not stability conditions are met at a higher level. This is of course the outcome of a model based on recursive operations, one that echoes Schenker's own notion of composing-out by means of voice-leading derivations.

is subsumed under the larger controlling tonic scale step, becoming part of a 5-6-5 contrapuntal expansion of the tonic. Examples 3a and 3c hold a structural parallelism. It follows, then, that in establishing the existence of a parallelism one should "climb up" the structural ladder in order to determine whether or not stability conditions are met at a higher level. This is of course the outcome of a model based on recursive operations, one that echoes Schenker's own notion of composing-out by means of voice-leading derivations.

Example 3. Varying stability conditions of motivic parallelism, Schubert, Ihr Bild (Schwanengesang)

One of the most significant consequences of the analytical operation just described is that it enables the proposition of motivic relations at the highest level of middleground. Motives are thereby released from the restrictive confines of surface design to take an active part in larger structural contexts. Reciprocally, the elemental voice-leading motions that characterize the high middleground—generic by nature—gain motivic status and are associated with immediately perceivable musical events. By the same token, however, with the traversal to the middleground, the perceptual import of the foreground motive is reversed, being rendered less immediate.

Now, the generality inherent in this type of motive threatens to trivialize the notion altogether. These motives are too adaptable, promiscuous even, students often remark! But it is precisely the degree to which a foreground event partakes of deeper structural events that determines its significance within the system. It follows that the concept of structural parallelism entails a mutual relationship between events belonging to discrete levels: one will neither identify, nor will one have the impulse to look for the "higher" event as a potential motive without the appearance of the "lower" one. It is in light of this interrelation, a conceptual two-way street of sorts, that it would be more appropriate to describe motivic parallelisms as "networks," since in networks two events can be related in multiple ways. The strict derivational hierarchy of the Schenkerian model is hereby neutralized.13

A free parallelism arises between the events in Examples 3a and 3b. This motivic connection clearly disregards structural derivation. Nonetheless, the notion of free parallelism shows enormous potential for the recognition of an ubiquitous compositional feature. This characteristic surely figures prominently among the reasons why most Schenkerians find the notion so compelling, even though it interferes with basic axioms of the Schenkerian paradigm.

If we are to continue harvesting the fruit of the Schenkerian motivic tree—and this includes, of course, free parallelisms within the voice-leading coordinates of Schenkerian analysis—we must adopt Cohn's revisionist proposition that the Ursatz must release its monopoly over all content, and that motives, once born out of the Ursatz, be granted autonomy to realize connections not always sanctioned by their progenitor. With this in mind we may now return to Schoenberg's concept of motive.

III

As the opening quotation asserts, the total vision of a composition is a fundamental desideratum that depends largely on prefiguring potential thematic realizations of a motive by means of thematic development. In a way, this motive or basic idea constitutes a concrete representation of the composer's vision.14 According to Schoenberg, the presence of the motive in every larger part may guarantee that coherence and comprehensibility are attained. In other words, the coherence of a musical work depends as much on the interrelation of parts within the whole as it does for Schenker. In this important respect both these theorists share a crucial first principle. Moreover, Schoenberg, like Schenker, also invokes the organic metaphor of the motive as a seed holding potential for content growth. What separates them are their individual conceptions of what the whole is. Whereas for Schoenberg—the composer—each vision of the totality must be a new one, a unique and individual idea ripe with possibilities for development, for Schenker—the theorist—there was an eternally enduring idea to be realized differently in every work, a position summed up in his motto "Always the same, but not in the same manner" (Semper idem sed non eodem modo). On final analysis there remains a profound schism between the late Schenkerian paradigm of derivation (or structural embedding) and the Schoenbergian paradigm of association (or concatenation of events). An epistemological reconciliation at this level is simply utopian.

This stark conclusion should not deter us, however, from looking into ways in which individual elements from these paradigms might be commensurable. Our acceptance of a motivic category that acts autonomously from the Ursatz opens an avenue of communication with other motivic conceptions, including, of course, Schoenberg's. Simply put: if we accept motivic parallelisms that do not subscribe to the restrictions of the Ursatz, why not then intermingle these with other motivic types? In Cohn's reconfigured Schenkerian terms, motivic analysis is primarily guided by the principle of association, a principle that also subtends Schoenberg's own notion of musical coherence. Furthermore, if the conceptual strictures surrounding late Schenkerian theory are to be made less dogmatic, we must de-idealize some of its basic tenets on musical unity and coherence. Schenker's earlier views are a good place to start, since the Schenker of Harmonielehre, as stated before, is far more receptive to the implications of motivic associations for the unfolding of a piece. We ought not to abandon the spirit of the Schenker who once wrote,

The life of a motive is represented in an analogous way to the way in which men are led through situations in which their characters are tested . . . so that one feature is revealed in each situation. . . . At one time, a motive's melodic character is tested, at another . . . a harmonic peculiarity must prove its strength in unaccustomed surroundings . . . in other words, the motive lives through its fate, like a character in a drama.15

Unwittingly echoing Schenker's position in the early writings, Schoenberg too embraces the complete musical complex that constitutes a motive: a soprano-bass counterpoint and a harmonic plan, as well as a particular rhythmic design, contour, and expressive character.

If we wish to adopt a strategy for reconciling varying theoretical conceptions of motive we must begin with Schenker, for any such strategy should enjoy the benefits of the Schenkerian model in its power to represent long-range connections. After all, Schoenberg's model is not at odds with the diachronic processes of the middleground and foreground levels. Motives, in short, are to be observed as they interact with the voice-leading events that the Schenkerian model makes available to our understanding.

From Schoenberg we must borrow the notion that events stated at the outset of a piece present multiple, if not infinite, implications for the development of the piece and that the realization of these implications contributes not only to compositional coherence but also to the experiential engagement of a listener. Here the motive has increasing significance as a motivator, as something that incites actions and provokes reactions. As Schoenberg succinctly states, "a motive is something that gives rise to a motion."16 We must not, however, reduce his insights to a tautological identification of the thematic in the manner of Rudolph Réti.17 It really is not musically insightful or perceptually interesting to point out return after return of, for example, a major second here and there if these returns are not put into a larger perspective of tonal unfolding, either as voice-leading processes or as formal or dramatic developments. The kind of opportunistic attitude I propose constitutes a viable alternative if we are to experience a richer reading of the motivic content of a piece. As I will now illustrate through analysis, we enjoy the best of both worlds.

IV

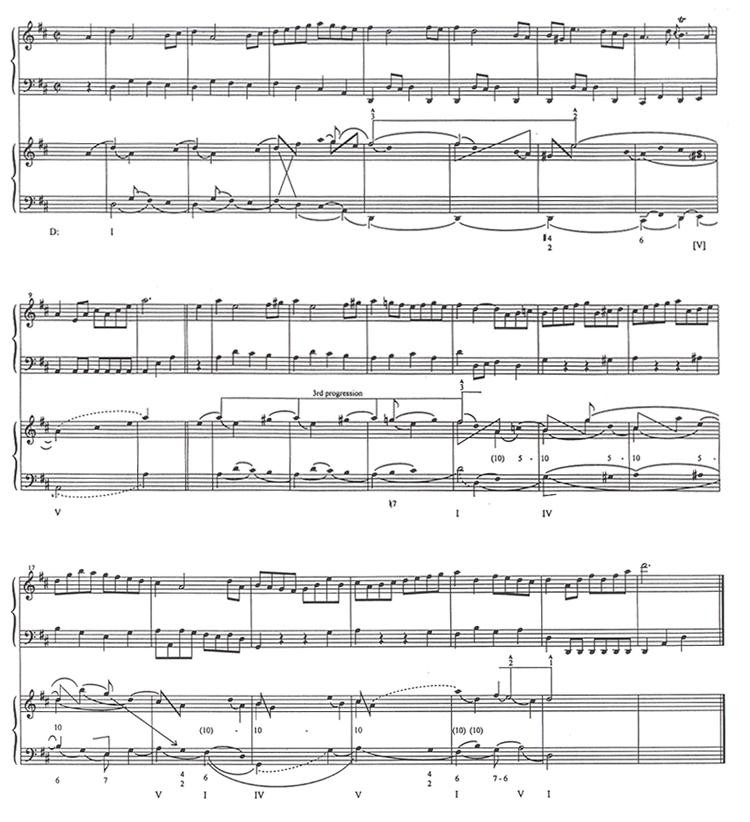

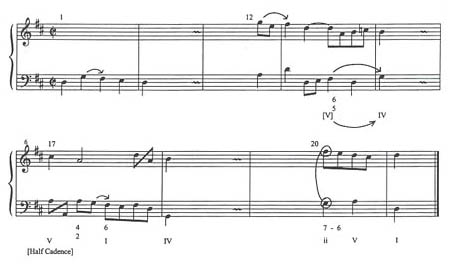

We will now consider the previous theoretical discussion in the context of an actual musical setting. In spite of its modest dimensions, this childhood favorite is a rich mine of compositional devices. Example 4 shows the score and the voice-leading graph that will provide the harmonic and contrapuntal forum in which to discuss motivic associations. In keeping with Schoenberg's pronouncement, we will follow the piece as it unfolds, so to speak, proposing a possible motivic story line.18

Example 4. C.P.E. Bach (attributed), March from the Notebook of Anna Magdelena

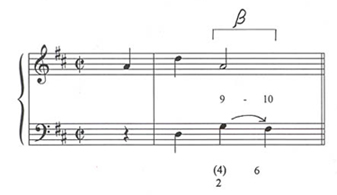

To begin, Example 5 identifies a first motive alpha at the outset consisting in a consonant skip a1-d2 within the control of the tonic scale step, a voice-leading description that qualifies the motive as a Schenkerian entity. The deceiving imitative impulse of the bass at the opening gives rise to the memorable bare major ninth at the second quarter-note of m. 1. This pregnant moment generates the two motivic elements indicated in Example 6: first, G (as a pitch class) becomes a sensitive tone by virtue of its prominent dissonant status, forming, even at this early stage, a potential  chord; second, because of its normative resolution to

chord; second, because of its normative resolution to  , G becomes intimately bound to this tone—represented by the arrow. We have then a motivic complex (labeled beta in the example) featuring contrapuntal and harmonic relations (that is, the dyad G-

, G becomes intimately bound to this tone—represented by the arrow. We have then a motivic complex (labeled beta in the example) featuring contrapuntal and harmonic relations (that is, the dyad G- and the

and the  sonority, respectively), and also presenting the single tone G. Together these elements have the potential for motivic roles, either as individual events or as combined elements. The term referential motive identifies precisely this kind of complex (i.e., a sonority, be it a chord, a contrapuntal structure, a dyad, or a single pitch class or pitch) that allows a network of associations or references to emerge that would not be available through motivic parallelisms.

sonority, respectively), and also presenting the single tone G. Together these elements have the potential for motivic roles, either as individual events or as combined elements. The term referential motive identifies precisely this kind of complex (i.e., a sonority, be it a chord, a contrapuntal structure, a dyad, or a single pitch class or pitch) that allows a network of associations or references to emerge that would not be available through motivic parallelisms.

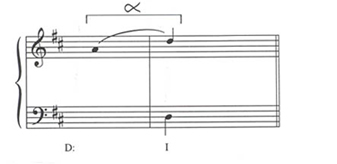

Example 5. Foreground motive alpha

Example 6. Referential motivic complex beta

As I suggested before, the referential motive is closer in conception to the Schoenbergian motive. It may be in fact considered a subset of Schoenberg's motive. For one, the latent references available in beta correspond to what Schoenberg calls the basic idea, a musical gesture where no element is considered ancillary and where any and all elements have developmental potential.19 Schoenberg's definition of motive includes the smallest event within a musical shape, "if permitted to have an effect, even an individual tone can carry consequences."20 Here, the individual tone G poses an enigma concerning its harmonic significance.21 I have suggested the sonority  as a plausible, though inconclusive, explanation. Equally, we may venture a linear explanation, namely, that G derives from an implied A in an equally implied tenor part in the first beat of the measure. Whatever the case may be, the indeterminate nature of G invites exploration of further appearances in order to establish a plausible identity.

as a plausible, though inconclusive, explanation. Equally, we may venture a linear explanation, namely, that G derives from an implied A in an equally implied tenor part in the first beat of the measure. Whatever the case may be, the indeterminate nature of G invites exploration of further appearances in order to establish a plausible identity.

The opening gesture reveals another more concrete Schoenbergian motive, as shown in Example 7. As a discrete gesture, this motive constitutes the sum of the two motivic types identified thus far. My description of this gesture as the "syncopated-leaping-fourth motive" echoes a Schoenbergian gestural reading where, again, rhythm and contour are given salience.

Example 7. "Syncopated leaping-fourth motive"

The parsing of this simple opening prompts a basic question concerning the nature of motivic analysis: are we not excessively fragmenting what is basically a single musical gesture, and thereby falling for the forbidden fruit of over-interpretation? After all, the musical surface renders invisible my uneasy superimposition of motivic types. An appropriate answer to these questions leads us to the second half of the composition, where much of its dramatic unfolding takes place, particularly through the strong sense of urgency created by the sequential passage at mm. 13 to 16.

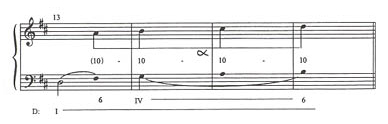

As indicated by the graph in Example 4, a 5-10 linear intervallic pattern unifies the passage. But only beginning with m. 14 is there a strict sequence, one in which all voices are involved in systematic repetition (notice the bass D on the last quarter of m. 13). Furthermore, while at the surface level the motion in the descant in m. 13 still observes the characteristic syncopation emphasizing the second quarter-note, at the beginning of the sequence the emphasis shifts to the downbeat in m. 14. This rhythmic turn helps to emphasize the lower-register notes b1- 2-d2 (mm. 14, 15, and 16, respectively); these tones constitute the leading voice of the passage. A proper evaluation of their structural standing is necessary to establish their motivic status.

2-d2 (mm. 14, 15, and 16, respectively); these tones constitute the leading voice of the passage. A proper evaluation of their structural standing is necessary to establish their motivic status.

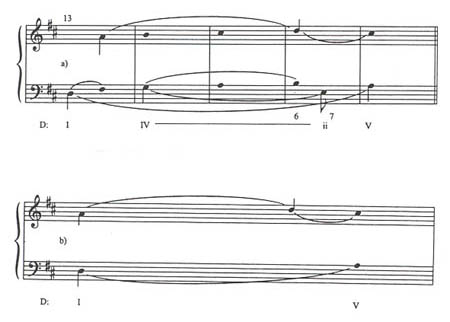

Example 8a. Motive alpha at middleground, free parallelism

Example 8b. Motive alpha at high middleground, structural parallelism

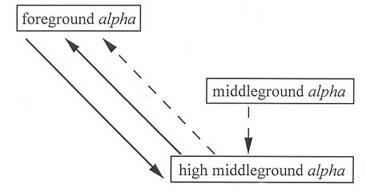

Example 8 shows the motivic content of the passage. The surface design of the strict sequence facilitates hearing an ascending third b1- 2-d2 composing out the subdominant scale step. It would be hard, however, to disregard the a1 in m. 13 in order to form a single motion in parallel tenths. The inclusion of a1 adds another harmonic level, ideally represented by the layered Roman numerals in the graph. It follows then that at this level the proposed motive alpha is not a structural event akin to the consonant skip motion of the anacrusis to m. 1. Because of its lower structural rank as a member of the subdominant scale step, the third b1-d2 is best heard as a suffix expansion to the higher ranking a1. To posit a motivic relation at this stage would entail recognizing a free parallelism. Further up the structural ladder, however, we find that once the subdominant scale step recedes, the bare a1-d2 motion is subsumed under the tonic scale step, as represented in Example 8b. At this level there arises a structural parallelism between the foreground and high-middleground versions of alpha. In this sense, the latter instance of alpha in its lower-middleground incarnation (i.e., the free parallelism shown in Example 8a) constitutes a filling-in of the boundary intervallic span of the higher-middleground motion a1-d2. The diagram of Figure 1 illustrates the network of associations of this motivic parallelism and serves to show, however rudimentarily, the complexity inherent in this type of motivic relation. Double arrows in opposite directions indicate a direct association among elements of the network; dotted arrows indicate an indirect one: the parallelism between the lower middleground version of alpha and the foreground version of alpha cannot be "known" without the intervention of the higher middleground version.

2-d2 composing out the subdominant scale step. It would be hard, however, to disregard the a1 in m. 13 in order to form a single motion in parallel tenths. The inclusion of a1 adds another harmonic level, ideally represented by the layered Roman numerals in the graph. It follows then that at this level the proposed motive alpha is not a structural event akin to the consonant skip motion of the anacrusis to m. 1. Because of its lower structural rank as a member of the subdominant scale step, the third b1-d2 is best heard as a suffix expansion to the higher ranking a1. To posit a motivic relation at this stage would entail recognizing a free parallelism. Further up the structural ladder, however, we find that once the subdominant scale step recedes, the bare a1-d2 motion is subsumed under the tonic scale step, as represented in Example 8b. At this level there arises a structural parallelism between the foreground and high-middleground versions of alpha. In this sense, the latter instance of alpha in its lower-middleground incarnation (i.e., the free parallelism shown in Example 8a) constitutes a filling-in of the boundary intervallic span of the higher-middleground motion a1-d2. The diagram of Figure 1 illustrates the network of associations of this motivic parallelism and serves to show, however rudimentarily, the complexity inherent in this type of motivic relation. Double arrows in opposite directions indicate a direct association among elements of the network; dotted arrows indicate an indirect one: the parallelism between the lower middleground version of alpha and the foreground version of alpha cannot be "known" without the intervention of the higher middleground version.

Figure 1. Motivic association of alpha

A direct motivic association exists between alpha from Example 5 and the ascending descant motion in the second half of m. 1. This association resides on the surface and constitutes an artful and interesting example of developing variation of the Schoenbergian "syncopated-leaping-fourth motive." One does not, however, need a convoluted Schenkerian voice-leading explanation to appreciate this relation. Likewise, the stretto-like motion D-G in the bass and its filling through the descending fourth G- -E-D may be regarded as the earliest response to the proposition of alpha. But, again, the ingenious contour inversion between bass and descant in m. 1 does not find validation under the Schenkerian model. Incorporating this into our analytical discourse requires that we invoke Schoenbergian concepts of shape, which we must do if we are not to disregard significant events in the piece.

-E-D may be regarded as the earliest response to the proposition of alpha. But, again, the ingenious contour inversion between bass and descant in m. 1 does not find validation under the Schenkerian model. Incorporating this into our analytical discourse requires that we invoke Schoenbergian concepts of shape, which we must do if we are not to disregard significant events in the piece.

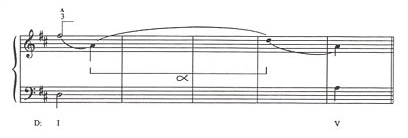

The attentive ear would certainly have noticed that the segmentation from which I obtain the free parallelism in Example 8a goes against the grain of the phrase structure of the passage. To be sure, because of its tightly-knit contrapuntal structure, the sequence creates a kind of bracket that encourages hearing a parallelism through which we can appreciate the completion of the ascending fourth on the downbeat of m. 16. But the larger goal of the sequence is the dominant at m. 17. Example 9 shows two levels at which the span of this motion (an ascending fourth—a1-d2—followed by a descending step—d2- 2) projects another free parallelism, this time in association to elements of beta. The parallelism shown at 9b presents a similar voice-leading structure to that of the bass of m. 1: in m. 1, G resolves to

2) projects another free parallelism, this time in association to elements of beta. The parallelism shown at 9b presents a similar voice-leading structure to that of the bass of m. 1: in m. 1, G resolves to  , here in mm. 16-17 d2 forms a seventh over the supertonic scale degree that resolves to

, here in mm. 16-17 d2 forms a seventh over the supertonic scale degree that resolves to  2 over the dominant. Here the harmonic motion from tonic to dominant changes the stability conditions of the initial version beta, making this a free parallelism. In all, the nested reverberations of alpha and beta in Examples 8 and 9 illustrate the pervasiveness in mm. 13-17 of echoes of the opening gesture of the composition. The March materializes ideas latent in the initial idea (or vision, in Schoenberg's parlance), painlessly, it seems, connecting many details in the piece.

2 over the dominant. Here the harmonic motion from tonic to dominant changes the stability conditions of the initial version beta, making this a free parallelism. In all, the nested reverberations of alpha and beta in Examples 8 and 9 illustrate the pervasiveness in mm. 13-17 of echoes of the opening gesture of the composition. The March materializes ideas latent in the initial idea (or vision, in Schoenberg's parlance), painlessly, it seems, connecting many details in the piece.

Example 9. Free parallelism with beta

These details include also the development of the referential tone G. A prominent feature of the passage from mm. 13 to 20 is the expansive presence of the subdominant. As the root of this scale step, the tone G (from the motivic complex beta) is granted consonant and harmonic status. Retroactively, therefore, we may venture a reading of the enigmatic opening measure according to which G (in the bass) sets up a rivalry of sorts against  , the tone to which it resolves, motivating latter exchanges. Notice, for instance, that as late as m. 12, the pitch-class G (as g2) remains a dissonance. From mm. 12 to 13 the change in the hierarchical relationship between G and

, the tone to which it resolves, motivating latter exchanges. Notice, for instance, that as late as m. 12, the pitch-class G (as g2) remains a dissonance. From mm. 12 to 13 the change in the hierarchical relationship between G and  is signaled by the bass motion

is signaled by the bass motion  to G, with

to G, with  becoming a dependent tone when C-natural appears in the descant. This turn of events is intimately bound to the voice-leading processes represented in the graph. But the Schenkerian model can only point to these as an aside, utilizing either verbal description or the most malleable of all Schenkerian symbols, the exclamation mark. We need thus a complementary means to accommodate pitch-class order and registral aspects of motives, to give just two domains not usually addressed by voice-leading concerns. I believe that the Schoenbergian and referential motives satisfy this analytic necessity. Example 10 traces the various tonal and registral environments in which G can be heard as a motive.

becoming a dependent tone when C-natural appears in the descant. This turn of events is intimately bound to the voice-leading processes represented in the graph. But the Schenkerian model can only point to these as an aside, utilizing either verbal description or the most malleable of all Schenkerian symbols, the exclamation mark. We need thus a complementary means to accommodate pitch-class order and registral aspects of motives, to give just two domains not usually addressed by voice-leading concerns. I believe that the Schoenbergian and referential motives satisfy this analytic necessity. Example 10 traces the various tonal and registral environments in which G can be heard as a motive.

Example 10. G as referential motive

Example 10 also indicates further instances of the referential motive that reflect an underlying tension spanning the passage beginning at m. 14. This tension is created by the transformations of G, the referential tone, as "its character is tested in unaccustomed surroundings," to recall Schenker. At m. 17 there is a half cadence; it is indeed a fleeting  chord which reintroduces the tonic harmonic scale step on the third quarter-note of the bar. At this point, of course, G is demoted to the level of dissonance. But immediately after, in measure 18, G gains access to a privileged registral stratum so far reserved for the main harmonic characters of the piece, namely the tonic and the dominant (see mm. 4-5 and 7-8 in the score). This registral appropriation is cleverly foregrounded by the horizontal major seventh the bass outlines at mm. 17-18 (see Example 4). A final, rather poignant instance of the referential dyad G-

chord which reintroduces the tonic harmonic scale step on the third quarter-note of the bar. At this point, of course, G is demoted to the level of dissonance. But immediately after, in measure 18, G gains access to a privileged registral stratum so far reserved for the main harmonic characters of the piece, namely the tonic and the dominant (see mm. 4-5 and 7-8 in the score). This registral appropriation is cleverly foregrounded by the horizontal major seventh the bass outlines at mm. 17-18 (see Example 4). A final, rather poignant instance of the referential dyad G- occurs in connection with the final descent of the Urlinie, a culminating event in the narrative of a Schenkerian analysis. At the very moment at which scale degree 3 moves to scale degree 2 (m. 20) it is G which, paradoxically, acts as the bass "support" to

occurs in connection with the final descent of the Urlinie, a culminating event in the narrative of a Schenkerian analysis. At the very moment at which scale degree 3 moves to scale degree 2 (m. 20) it is G which, paradoxically, acts as the bass "support" to  in the 7-6 motion. This vertical conflation is the last vestige of beta. G, it follows, has the final word.

in the 7-6 motion. This vertical conflation is the last vestige of beta. G, it follows, has the final word.

V

In closing, I would like to observe that the underlying assumption of my presentation may not need validation. Even on the wake of strong intellectual challenges made to so-called organicist approaches, it is impossible to deny that much tonal music from the common-practice period exhibits an extraordinary degree of coherence. So no ground-breaking news in that regard is offered here. Indeed, some important questions remain unanswered, such as the issue of form in Schenker and Schoenberg, or the radical difference between, on the one hand, a compositional principle aimed at writing non-tonal music (as reflected in the title of Schoenberg's essay quoted at the beginning) and, on the other, an analytical model designed to explain tonal music.22 But I suggest that fertile grounds for reconciliation are found at the pragmatic level of motivic analysis. The motivic triad I bring together works well because its individual members are best enjoyed, so to speak, when seen in the light of the particular ways in which together they generate musical content. These motivic types are in this sense true motivators. The analytical narrative made possible by adopting a pluralistic attitude toward motivic analysis is simply richer: the voice-leading Schenkerian motive illuminates the Schoenbergian motive and vice-versa. For students, consideration of Schoenbergian motives facilitates the discovery of subtle compositional devices. Likewise, Schenkerian parallelisms teach much about hearing on different structural levels, encouraging us to hear "beneath" the musical surface. Reconciliation, it follows, occurs on the practical side of theory, that is, at the level of analysis. For it is on analytical grounds that we seek to negotiate questions of structure in music. In its modest dimensions my musical example illustrates the immense power of the small detail and the significance that any and all motivic ideas, no matter how small, can have in tonal music. My analysis suggests the potential for developing motivic plot lines from the unfolding of motivic events. These are some of the goals of this brief study.

I have also represented motivic associations separate from the voice-leading graph, a practice that reflects their status as autonomous entities. In keeping with the thematic of Cohn's proposition, I would suggest that not even the characteristic and ubiquitous Schenkerian flagged-note be included in a voice-leading graph as an index of motivic status. This distinction would make clear the conceptual grounds for each notion of motive. It remains our task as instructors, however, not only to spell out these distinctions, but also to bring together these conceptions. The goal is to have flexibility in teaching about various kinds of musical coherence. I, for instance, do not often have the need to present a thorough account of motives in the manner exemplified by the analysis of the "March in D." But in teaching a class on voice-leading, for example, I have found it effective to introduce the notion of referential motive. Consider the case of the opening phrase from J. S. Bach's setting of the chorale "Wer hat dich so geschlagen," from the St. John Passion (Example 11). In m. 1, the accented passing tone  1 in the bass on the second beat forms an exquisite, yet biting, dissonance against the tenor d1. This occurs in the context of a middleground prolongation of the tonic via IV and vii6 connecting the upbeat to m. 1 to the third beat of m. 1. After explaining the normative version of the voice leading there, in which

1 in the bass on the second beat forms an exquisite, yet biting, dissonance against the tenor d1. This occurs in the context of a middleground prolongation of the tonic via IV and vii6 connecting the upbeat to m. 1 to the third beat of m. 1. After explaining the normative version of the voice leading there, in which  would appear on the second eighth-note of the first beat as an unaccented passing tone prolonging IV (as shown in Example 12), one may then ask students to compare this moment with another version of the motivic dyad

would appear on the second eighth-note of the first beat as an unaccented passing tone prolonging IV (as shown in Example 12), one may then ask students to compare this moment with another version of the motivic dyad  -D, this time having migrated to the soprano and alto parts on the first beat of m. 2 (note also the key gap between tenor and alto which isolates the sonority). What is the voice-leading role of

-D, this time having migrated to the soprano and alto parts on the first beat of m. 2 (note also the key gap between tenor and alto which isolates the sonority). What is the voice-leading role of  2 in the alto here? The class may answer that it behaves as a suspension, but that the bass is uncooperative—against it, the alto forms a contrapuntally irregular 5-4 succession. While the local prolongation of the subdominant D is fairly clear in the outer-voice counterpoint (thanks to the applied dominant on the fourth beat of m. 1), the voice-leading in the inner voices resists an unambiguous interpretation. Here, one may profitably appeal to the concept of motive. That is to say, the register shift can be said to constitute a reaction to the biting dissonance in the lower voices one measure earlier, which here results in a more euphonious version of the dyad

2 in the alto here? The class may answer that it behaves as a suspension, but that the bass is uncooperative—against it, the alto forms a contrapuntally irregular 5-4 succession. While the local prolongation of the subdominant D is fairly clear in the outer-voice counterpoint (thanks to the applied dominant on the fourth beat of m. 1), the voice-leading in the inner voices resists an unambiguous interpretation. Here, one may profitably appeal to the concept of motive. That is to say, the register shift can be said to constitute a reaction to the biting dissonance in the lower voices one measure earlier, which here results in a more euphonious version of the dyad  -D in the high register. More to the point, one may suggest that the

-D in the high register. More to the point, one may suggest that the  1 in the alto is motivated by a compositional desire to exploit the minor second sonority, which also bears upon the setting of the word "geschlagen." This brief example would provide a vivid and audible introduction to subtle compositional designs that, in incorporating notions of motivic register, sonority, and prolongation, broaden the scope of the analytical concerns of a beginning or intermediate theory class.23

1 in the alto is motivated by a compositional desire to exploit the minor second sonority, which also bears upon the setting of the word "geschlagen." This brief example would provide a vivid and audible introduction to subtle compositional designs that, in incorporating notions of motivic register, sonority, and prolongation, broaden the scope of the analytical concerns of a beginning or intermediate theory class.23

Example 11. J.S. Bach, St. John Passion, "Wer hat dich so geschlagen"

Example 12. Normative version of  1: unaccented passing tone

1: unaccented passing tone

On a more general note, what I hope to have shown is that a change in our attitude towards paradigms is in place. There are telling signs that the oscillation between normal theory and revolutionary theory has shaken our community. Normal theory (in Thomas Kuhn's sense), or better yet, normal analysis, cannot be practiced in good conscience these days. We find ourselves re-examining the epistemology of our most cherished models (for instance, Riemann, Schenker, Schoenberg). Some choose to reject these models, keeping only a few basic notions at hand. But some are willing to revise basic tenets so as to accommodate them within an expanded analytical enterprise. I stand with the second group. Students of analysis benefit greatly from a pluralistic approach that openly addresses the kinds of questions analysis raises; this draws their attention to the assumptions we make when adopting one analytical strategy or another. In the final analysis (no pun intended), the opportunistic attitude advocated here recognizes the possibilities and limitations of theoretical constructs and the urgency of keeping our ears open to the wealth of associations music affords.

1Arnold Schoenberg, "Composition with Twelve Tones," in Style and Idea, ed. Leonard Stein with trans. Leo Black (London: Faber, 1975), 215.

2Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition, Vol. 3 of New Musical Theories and Fantasies, ed. and trans. Ernst Oster (New York: Longman, 1979), 131.

3The radical difference between Schoenberg's and Schenker's conception of musical content is discussed in Carl Dahlhaus, "Schoenberg and Schenker (Controversy Concerning the Significance of Non-Chordal Notes)," Proceedings of the Royal Music Association 100 (1973-1974): 209-215.

4Richard Cohn, "The Autonomy of Motives in Schenkerian Accounts of Tonal Music," Music Theory Spectrum 14 (1992): 150-70.

5The concept of referential motives is discussed in Milton Babbitt, Words About Music, eds. Stephen Dembski and Joseph N. Straus (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 138-39. See also James Sobaskie, "Associative Harmony: The Reciprocity of Ideas in Musical Space," In Theory Only 10 (1987): 31-64.

6Heinrich Schenker, Harmony, Vol. 1 of New Musical Theories and Fantasies, ed. and annotated by Oswald Jonas with a translation by Elizabeth Mann Borgese (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1954), 4-5.

7This parallelism is analyzed, from a different perspective, in Fred Lerdhal and Ray Jackendoff, A Generative Theory of Music (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1983), 253.

8Schenker, Free Composition, 18.

9Helmholtz's octave designation system is used throughout the article (e.g., c1 refers to middle c).

10Cohn, who calls the process of structural definition "mode of derivation," offers an illustration by Carl Schachter where several possible interpretations of a descending-fourth span (without contrapuntal or harmonic support) are considered (Cohn: 159). My example takes into account the underlying harmonic and contrapuntal framework.

11The notion of structure is typical of Schenkerian thought, not of Schenker's own work. Structure emerges as a useful trope for musical organization in that it conflates temporal and spatial metaphors. For a discussion of this conflation, see John Carlos Rowe, "Structure" in Critical Terms for Literary Study, eds. Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), 23-38.

12A similar analysis featuring this parallelism is given in the Instructor's Manual for Allen Forte and Steven Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1982), 106-07.

13Cohn (165-67) discusses temporal and spatial issues under the term "dual generation." With this term he refers to the often ambiguous cause-and-effect relationship between a pair of related motivic events, that is, the simultaneous generation of a motive from two distinct structural levels.

14Schoenberg's idea of basic idea may be ultimately undefinable. See Patricia Carpenter, "Grundgestalt as Tonal Function," Music Theory Spectrum 5 (1983): 15-38. Severine Neff discusses the various but conceptually equivalent definitions Schoenberg gave to Grundgestalt and Motiv in "Schoenberg and Goethe: Organicism and Analysis," in Music Theory and the Exploration of the Past, eds. Christopher Hatch and David W. Bernstein (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993), 416-418.

15Schenker, Harmony, 13.

16Arnold Schoenberg, Coherence, Counterpoint, Instrumentation, Instruction in Form, ed. with an introduction by Severine Neff and translated by Charlotte M. Cross and Severine Neff (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 27. See also Severine Neff, "Schoenberg and Goethe," 432-433 n. 36.

17Rudolph Réti, The Thematic Process in Music (New York: Macmillan, 1951).

18The story will echo Schenker's comparison of the motive to a character in a drama, and also Schoenberg's statement that "[each composition raises] a question, puts up a problem, which in the course of the piece has to be answered, resolved, carried through. It has to be carried through many contradictory situation [sic]; it has to be developed by drawing consequences from what it postulates . . . and all this might lead to a conclusion, a pronunciamiento." Undated English manuscripts, quoted in Neff, "Schoenberg and Goethe," p. 418. Marion Guck has examined the intersection of musical and metaphoric description and analytical narrative in a series of articles, including, "Musical Images as Musical Thoughts: The Contribution of Metaphor to Analysis," In Theory Only 5/v (1981), 29-43; "Two Types of Metaphoric Transfer," in Metaphor: A Musical Dimension, ed. Jamie C. Kassler (Paddington, NSW: Currency Press, 1991), 1-12; "Rehabilitating the incorrigible," in Theory, Analysis and Meaning in Music, ed. Antony Pople, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 57-73. See also Fred Everett Maus, "Music as Drama," Music Theory Spectrum 10 (1988): 56-73.

19See footnote 14, above.

20Schoenberg, Coherence, 27.

21Referential motives often correspond to what Patrick McCreless, in an adaptation of Roland Barthes's codes for reading, calls the hermeneutic code. A hermeneutic code refers to an enigmatic event usually occurring near the beginning of a tonal composition that holds the promise, as it were, for further developments and eventual clarification. (A paradigmatic example is the  near the beginning of Beethoven's Eroica.) See Patrick McCreless, "Roland Barthes's S/Z from a Musical Point of View," In Theory Only 10 (1988): 1-29.

near the beginning of Beethoven's Eroica.) See Patrick McCreless, "Roland Barthes's S/Z from a Musical Point of View," In Theory Only 10 (1988): 1-29.

22For an excellent introduction to this topic see Janet Schmalfeldt, "Towards a Reconciliation of Schenkerian Concepts with Traditional and Recent Theories of Form," Music Analysis 10 (1991): 233-87. See Dahlhaus, op. cit., for a discussion of the irreconcilable nature of Schoenberg's and Schenker's analytic practice.

23One may also compare this setting with other "harmonizations" of the same melody, establishing various possible kinds of motivic usage. This may be in turn studied within the different expressive aims within their setting in the Passions.