We often teach musical notation to beginners as if they were "blank slates," introducing them to the symbols and rules of notation without considering any preconceptions they might have about how to read music. Yet, one might assume that beginners (particularly adults) may arrive at their first music lessons with strong intuitions about what musical symbols might represent. It is difficult for music instructors to guess what these intuitions might be, or to imagine what notation might look like to someone who is musically untrained. We have learned to associate a musical symbol with its meaning to such a deep degree that it is difficult to see other possible interpretations of these symbols. We may assume that the link between the appearance and meaning of a musical symbol should be logical to our students, and may fail to see aspects of notation that are not immediately intuitive (or may even be counterintuitive) to beginners. With these issues in mind, we conducted ten and a half hours of intensive interviews with thirteen college students who could not read music in order to explore beginners' intuitions about how to read musical notation. The goal of this inquiry was not prescriptive, but descriptive. The aim was not to suggest that musical notation systems should be more visually intuitive, nor to provide principles toward a new notation system accessible to all. Our goal was simply to explore the questions: What correct and incorrect first impressions of the symbols and rules of musical notation might musically untrained adults have?

Western musical notation has its roots in the letter notation of ancient Greece (Apel, 1949; Hoppin, 1978; Randel, 1999; Read, 1969), with the earliest forms of diastematic notation (representation of precise pitches) appearing in the eleventh century and mensural notation (representation of note durations) emerging in the late thirteenth century (Randel, 1999). Its development was strongly influenced by the Western value placed on precision in depicting discrete pitches, and temporal and expressive elements of music. As it evolved, musical notation became increasingly conventionalized and less visually intuitive. As Walker (1981) noted, "staff notation has developed over the centuries, not as a visual counterpart of reflection of sounds, but rather as a mnemonic in respect to musical actions."

Indeed, recommendations to make standard music notation more iconic (e.g., Cromleigh, 1977; Gaare, 1997; Osborn, 1966) are often met with resistance from the musical community, and unconventional notational systems that link visual and auditory modes more directly (e.g., Cage & Knowles, 1969; Gaare, 1997; Walker, 1992) have not taken hold among mainstream musicians. For example, in an early investigation of the readability of musical notation, Wheelwright (1939) addressed questions such as whether the size of accent marks should be varied to correspond to the recommended intensity. Although responses of music educators varied, dissenters argued:

"No, that is a problem for the ear" [i.e., not the eye] (p. 27, emphasis added).

"If the pupil is musical this item should take care of itself, and if the pupil is not musical the size of accent is only making a surface interpretation" (p. 27).

Similarly, in response to the question of whether melodic lines should be printed in larger sizes of notation than harmony, the following objection was raised:

"I feel this would be an unnatural distortion, a 'crutch' which if children never use they will never miss" (p. 27).

A legitimate concern may be that a musical notation system that is strongly visually intuitive may lead performers to approach music as an art form that is visually prescribed—rather than one that is aurally driven and in which musical meaning and expressivity lie beyond the score. A conventionalized notation system requires a certain level of musical training that may be needed to "read between the lines" in order to capture the richness and subtleties of the art form. It also creates some distance between vision and sound, reminding the performer that the score is after all only an incomplete representation of the music itself (Campbell, 1991; Lester, 1995; Rothstein, 1995) rather than a direct visual translation of the sounds.

Previous studies have examined musically untrained individuals' ideas of how musical sound can be represented visually. For example, in a series of studies Walker (1978; 1981; 1987) asked children and adults to match musical sounds with visual representations (e.g., geometric shapes, abstract symbols, and patterns). He found that there was a high level of agreement among the responses: specifically, participants tended to associate size of a symbol with loudness of sound (so that larger symbols depicted louder sounds), rising vertical placement with rising pitch, placement along the horizontal axis with temporal spacing of sounds, and shape or texture with timbre. Another examination of adults' invented iconographic representations of short musical excerpts yielded similar results to Walker's findings (Eastlund-Gromko, 1995). Like Walker, Eastlund-Gromko found that in their invented notations, adults tended to use size to depict intensity, height on the page to depict pitch, and placement along the horizontal axis to represent duration. Similar results have been found in studies of visual representations of music created by children five years and older (e.g., Davidson & Scripp, 1988; Eastlund-Gromko, 1994; Hair, 1993; Upitis, 1990; Walker, 1978).

While previous studies have examined how musically untrained individuals invent unconventional ways of visually depicting music, we are not aware of any studies that have addressed how musically untrained individuals might interpret conventional musical notation. To this end, the present inquiry was undertaken.

The Interviews

Individuals interviewed: Thirteen college students (seven males and six females, aged 17 to 21 years old) who could not read musical notation were individually interviewed for a total of ten and a half hours. None of the students had received any instruction on how to read musical notation before participating in the study (not even in classroom music instruction in elementary school or through informal instructions from a friend), and none had taken any private instrumental or voice lessons. Students who reported that they were "uncertain" whether they had ever learned how to read music, or "used to know how to read music but forgot" were not included. Those who were interviewed for the study are hereafter referred to as either interviewees or "non-readers," to emphasize that they could not read music and had never received instruction on music reading.

Music used: We wanted to present musical symbols to the interviewees in their proper context (i.e., as they appear in actual pieces of music)—not as isolated musical symbols on a blank page. Therefore the music used in the interview were single-page excerpts from an intermediate-level piano method book (The Big Book of Classical Music, 1999), employing standard western music notation. Single-page excerpts were selected, and all titles, composers' names, and any other English words were removed so as not to influence the interviewees.

Style of interview: The thirteen interviewees were questioned individually for approximately 50 minutes each. In all, a total of over ten and a half hours of interviews was conducted. The interview technique employed was similar to Piaget's clinical method (Ginsburg, 1997; Piaget, 1926/1930), in which open-ended questions are succeeded by more specific questions emerging from the interviewees' responses. The first question was:

Looking at this piece of music, can you point to anything on the page that immediately catches your attention for any reason?

This was to begin the interview by letting the interviewee select salient parts of the score, without the interviewers suggesting what the non-reader "should" be paying attention to in the music. Great care was taken by the interviewers to avoid asking leading questions, and to keep suggestions of new ideas to a minimum. We were also careful not to use technical terms, and to consistently employ the terminology that each interviewee spontaneously used (for example, if an interviewee referred to a measure as a "frame" or "segment," we would thereafter refer to it as "this item which you referred to as a 'frame'/'segment'"). All interviews were recorded, and later transcribed. The interviews yielded over 150 pages of transcriptions (i.e., approximately 30,000 words were transcribed).

Emerging themes were identified through an analysis of the transcribed interviews, using a grounded theory approach to qualitative analysis (Smith, 1985) whereby the themes emerged out of the interviewees' responses, as opposed to an a priori list of categories (which might reflect the researcher's preconceptions). In particular, we focused on the rationale that non-readers provided for their intuitions about the rules and symbols of musical notation.

Many different themes emerged, and only a small part of our observations are included in this discussion. The themes are grouped below as non-readers' incorrect intuitions about musical notation, and non-readers' correct intuitions about musical notation.

Interviewees' responses reflected many incorrect intuitions about musical notation. Their responses were often quite similar, which was surprising to us as we had expected their ideas to be somewhat more idiosyncratic.

A "note" is a quarter note with an upward stem: Everything else is just a variation.

Eight of the thirteen interviewees viewed the quarter note (with upward stem) as the standard symbol for a musical note (or in interviewee MB's words: "it is the universal note, or what I think a note should be"). Further, interviewees tended to interpret the meaning of other notes with respect to how it deviated from this standard—which led to some incorrect intuitions. For example, the half note was often viewed as an "incomplete note," a "hollow" or "empty" version of a note, or as "a note with a hole in the middle" because participants tended to compare it with the quarter note. Indeed, several believed that whole notes and any notes that did not have black note-heads denoted "silence" or "rests" because they were "hollow" or "empty." Most surprisingly, seven of the interviewees did not even know that whole notes and half notes were "notes" (or symbols that represented sounds) "because they look so different from real notes." Interviewee KJ described a half-note in the following way: "There is no note there there is a hole in the middle." RC stated: "only the black ones are notes: the white notes are something different that I don't know, but I know they are not notes."

One non-reader was baffled by the appearance of quarter notes with stems facing downward, again viewing it in comparison to what she believed to be the standard:

DW: They look like they are upside down. I've never seen notes that look upside down. The only notes that I am familiar with are, like, notes like that [quarter note, stem up] It just looks strange to look at it looking upside down.

Anything appearing on the staff that has dots or circles or hollows represents a sound/note.

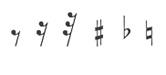

Four of the non-readers assumed that eighth, sixteenth and thirty-second rests as well as accidentals (especially flats) represented sounds. In KA's words: "I would have to guess that [all these symbols] are just different kinds of notes. They have that space in the middle for where, I think, the sound goes." Thus the following symbols were frequently mistaken as symbols of sound: eighth, sixteenth, and thirty-second rests; flats, sharps, and natural signs.

Five interviewees believed that all symbols with black circles depicted sound, while symbols with "hollow" spaces depicted silence. More specifically, quarter notes, eighth notes, sixteenth notes and also eighth rests, sixteenth rests, and thirty-second rests were taken to represent sounds, while half and whole notes and symbols for the flat and sharp and natural were believed to represent absence of sound. In RC's words: "Anything with the black dots probably means you play it, and anything with white or nothing inside probably means you don't play it."

On the other hand, four of the remaining non-readers did not know that the note-head indicates the pitch of a note. Instead, they paid attention to the stem and suggested that notes with stems pointing upward indicate sounds that slide up in pitch, while those with stems pointing downward represent sounds that slide down in pitch. (When asked to demonstrate, the interviewees made sounds resembling upward and downward glissandi). Two of these non-readers went on to say that the "little tails" extending from eighth notes indicated a change in the direction of the pitch (e.g., upward glissando followed by downward glissando).

More ink, larger size, and more features indicate "more of something."

Nine interviewees believed that the more black ink a note contained, the greater its value. Thus, they assumed that black notes were worth more than white notes. For example, when asked to compare half notes and quarter notes, KA stated: "The black ones would be longer than the ones with hollow spaces There is more substance to the actual note, so I would just assume that there is more time in it." With respect to size, nine interviewees concluded that taller symbols were worth more than smaller symbols. For example, BW and MB believed that a half note was "worth more than" a whole note because the half note is "taller." Interviewees also tended to think that the value of a note increased with increasing number of features. For example, KJ and NL pointed to the black dots in the eighth and sixteenth rests and stated: "One is one thing, two has got to be more of it."

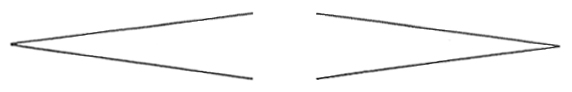

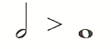

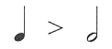

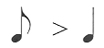

The intuitive "rules" that more ink, larger size, and greater number of features indicate more of a certain dimension led non-readers to envision a hierarchy of notes and rests as depicted in Figure 1. (Note that in each case, the reverse is true with respect to note duration).

Figure 1. Hierarchy of Notes and Rests according to Non-readers' Reports:

a half note is "more" than a whole note

a quarter note is "more" than a half note

an eighth note is "more" than a quarter note

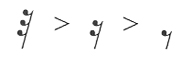

a thirty-second note is "more" than a sixteenth note; a sixteenth note is "more" than an eighth note

a thirty-second note rest is "more" than a sixteenth note rest; a sixteenth note rest is "more" than an eighth note rest

There was considerable variety regarding what interviewees believed that the appearance of a note denoted. Only two suggested that it might indicate durational value. The rest believed that the appearance of a note might indicate: loudness ("black notes are louder than white notes"); the number of notes to be played (thirty-second rest: "three dots mean play 3 notes together"); sixteenth rest: "two dots tells you to play 2 notes together"); the number of times a note should be played (thirty-second note should be "repeated three times because it has three stripes"), or style of playing ("play notes with 'sticks' plainly, and play notes with 'many tails' fancily or maybe with vibrato.")

Notes that are attached by a beam represent one single sound:

Seven non-readers thought that eighth notes or sixteenth notes attached by a beam represented "one note" and corresponded to "one sound."

DW: I think it is one note, one sound.

Interviewer: One note?

DW: One note because they are hooked together.

In a few cases, three or more notes attached by a beam were also taken to be "a chord" or "many notes played at the same time." The idea that non-readers did not see each note-head as a representation of one sound was surprising to us, and we did not pay attention to this until a non-reader mentioned it to us. We may have suggested that groupings consist of many individual notes by implying it in our questions to some interviewees who may not otherwise have known this.

The spacing between notes refers to how much time lapses between them (the pacing of the notes).

Most non-readers assumed that the horizontal axis of music was used to express the speed with which notes are played. This is certainly true in some cases (e.g., spacing between sixteenth notes is often twice the distance of eighth notes), but musicians primarily attend to the type of note itself to determine duration.

KA: I would think that they [the notes] would be played, like, one after another. And the closer they were, the closer they would be played together.

RC: Where the notes are all bunched up is where it is fast. Where they are all spaced apart, it is probably more leisurely.

If something always appears in the same place in the music, it is probably not important.

Symbols that always appear in the same location (especially in the beginning of each line of music) were not taken to convey important information. Specifically, clefs, time signatures, and key signatures were often viewed as "ornamental" or "purely decorative." In fact, these are often among the first symbols we introduce to beginners because of their fundamental importance to our musical notation system. DW's response was typical of the interviewees as a whole: "I suppose they [clefs, time signature] are just there to say where the music begins." Key signatures were also often regarded as decorative:

Interviewer: And what about the signs here [key signatures] next to those symbols [the clefs]?

PE: They were repeated throughout, like, in all the bars [staves] of music.

Interviewer: If something's "repeated throughout all the 'bars' of the music" (as you call these), would it appear to be something of great significance or something with no information?

PE: Something not very important.

Correct Intuitions of Musical Symbols:

Non-readers tended to have correct intuitions about the following symbols, reflecting that these symbols may be somewhat iconic or "direct" (i.e., visually suggestive of the quality of sounds they represent) to beginners.

Crescendo and decrescendo:

These were understood by most non-readers as signifying gradual increase and decrease of a particular dimension—usually volume or speed. PE, however, stated that it might mark parts of the music in which different parts played by different instruments would diverge and separate (crescendo sign), or converge and play together (decrescendo sign).

Phrases and slurs:

These were understood by most non-readers as signifying notes that were to be played in a connected or smooth fashion. KA, however, reported that it might refer to volume: "I guess one thing would be the actual volume of it. It starts out lower and increases as it goes up and then goes back down."

Quarter rests:

It surprised us that quarter rests were intuitively understood by almost all of the non-readers as denoting a "break" in the music (which is a mainly correct, though of course still quite elementary, understanding of the function of rests). We were interested to find that many stated that the rest looked like a "break" or a "tear." For example:

BB: It's kind of like, it looks like a break in the lines.

Interviewer: What about the way it looks makes it seem like it is a break, if you are correct on that?

BB: Because it just looks like a tear in the lines, like if somebody scribbled it instead of tearing it or something.

Concluding Remarks

The interviewees' responses suggest that adult beginners' intuitions about musical notation usually have a logical basis, even if their intuitions are incorrect. Further, it appears that learning musical notation involves memorization of meanings of symbols that may be counter-intuitive to the beginning music student. For example, the intuitive "rules" that many of the non-readers used to deduce relative value led them to rank order notes and rests in the reverse order from the sequence that is conventionally correct. Specifically, non-readers believed that black notes had greater value than white notes, taller symbols had greater value than smaller symbols, and that notes with many features had greater value than notes with few features—while in fact the opposite is often true. One reason that beginning students might repeat the same errors may be that they are fluctuating between their initial intuitions of what symbols might mean and conventionally "correct" meanings (which may be counter-intuitive to them).

Paying close attention to the wording, imagery, metaphors, and even gestures that beginning students use may give teachers clues about how their students are making sense of the symbols and rules of music (e.g., Bamberger, 1991). For example, I noticed that my co-interviewers and I (who are all musically trained) tended to refer to half notes and whole notes as "white." Many of the non-readers, however, described the notes as "hollow," "empty," "incomplete," "with nothing in the middle," and "with a hole in it." It is not surprising that students would have difficulty remembering that half notes have greater value than quarter notes if they see them as hollow or incomplete.

The study also lends support to the "sound before symbol" approach to music education (e.g., Bartholomew, 1995; Bruner, 1966; Campbell, 1991; O'Brien, 1974), whereby children are guided in their experience of elements of sound before they are introduced to the symbols that represent them. In this way, symbols are introduced as memory prompts for musical concepts, sounds, actions, and feelings that have already been made familiar—as opposed to visual labels for ideas which are not yet meaningful to them. In this study, the adult non-readers relied primarily on the appearance of symbols to deduce what they represent because they often assumed that musical symbols provide visual analogues for sound. When I explained to the interviewees at the end of the study that many musical symbols do not visually resemble the sounds they represent, most responded with a puzzled "Why not?" Further, the idea that written music is only a "guide" for the performer, who must "play more than the symbols can convey" was even more perplexing to them. Many assumed that written music is a complete prescription of what to play. BB (who became interested in music reading because of this study, and is currently taking college piano courses) astutely concluded: "I guess you have to develop a sense of music before you can completely grasp what the symbols stand for."

We are not recommending that teachers anticipate all possible misconceptions of musical notation, nor that they assume that all beginners have the same intuitions about how to read music. However, it is valuable for music instructors to have insight into beginning students' initial impressions of musical notation, and to be more aware that there are other (logical) ways to interpret the mysterious symbols which we call "music." Indeed, one of the most difficult things for educators in all disciplines to do is to see the basic materials of their trade through the eyes of new-comers, in order to make explicit the fundamental concepts that have become implicit through years of training and experience. For music instructors, it is valuable to know more about beginners' intuitions of the symbols and rules of musical notation. In Howard Gardner's (1991) words: "We must place ourselves inside the heads of our students and try to understand as far as possible the sources and strengths of their conceptions" (p. 253).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks research assistants Angela Kovalak, Stephen Haedicke, Kristin Alt, Aimee Topacio, Elaine Wieland, and Katie Kawel for their valuable contributions to various phases of this project, Esther Cleason for transcribing interviews, and Leslie Tung for comments on an earlier draft. We are all grateful to the Kalamazoo College students who consented to be interviewed for this study.

References

Apel, W. (1949). The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900-1600. Cambridge: Mediaeval Academy of America.

Bamberger, J. (1991). The Mind Behind the Musical Ear. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bartholomew, D. (1995). Sounds before symbols: What does phenomenology have to say? Philosophy of Music Education Review, 3, 1, 3-20.

Bruner, J.S. (1966). Toward a Theory of Instruction. MA: Harvard University Press.

Cage, J., & Knowles, A. (1969). Notations. NY: Something Else Press.

Campbell, P.S. (1991). Lessons From The World: A Cross-cultural Guide To Music Teaching and Learning. New York: Schirmer.

Cromleigh, R.G. (1977). Neumes, notes, and numbers: The many methods of music notation. Music Educators Journal, 64, 4, 30-39.

Davidson, L., & Scripp, L. (1988). Young children's musical representations: windows on music cognition. In J. A. Sloboda (Ed.), Generative Processes in Music, 195- 230. Oxford: Clarendon.

Eastlund-Gromko, J. (1994). Children's invented notations as measures of musical understanding. Psychology of Music, 22, 136-147.

Eastlund-Gromko, J. (1995). Invented iconographic and verbal representations of musical sound: Their information content and usefulness in retrieval tasks. The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, 6, 136-147.

Gaare, M. (1997). Alternatives to traditional notation. Music Educators Journal, 83, 5, 17-23.

Gardner, H. (1991). The Unschooled Mind. NY: Basic Books.

Ginsburg, H. P. (1997). Entering the Child's Mind: The Clinical Interview in Psychological Research and Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hair, H. (1993-4). Children's descriptions and representations of music. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 119, 41-48.

Hoppin, R. H. (1978). Medieval Music. NY: W.W. Norton.

Lester, J. (1995). Performance and analysis: interaction and interpretation. In (J. Rink, Ed.), The Practice of Performance, pp. 197-216. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

O'Brien, J.P. (1974). Teach the principles of notation, not just the symbols. Music Educators Journal, 60, 9, 38-42.

Osborn, L.A. (1966). Notation should be metric and representational. Journal of Research in Music Education, 12, 2.

Piaget, J. (1930). The Child's Conception of the World. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovitch. (Original work published 1926).

Randel, D. M. (1999). Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Notation. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Read, G. (1969). Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Rothstein, W. (1995). Analysis and the act of performance. The Practice of Performance, pp. 217-240. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, J. A. (1985). Semi-structured interviewing and qualitative analysis. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, and L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking Methods in Psychology (pp. 9-26). London: Sage.

The Big Book of Classical Music. (1999). Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard.

Upitis, R. (1990). Children's invented notations of familiar and unfamiliar melodies. Psychomusicology, 9, 89-106.

Walker, R. (1978). Perception and music notation. Psychology of Music, 6, 21-46.

Walker, R. (1981). The presence of internalised images of musical sounds. Council for Research in Music Education, 66-67, 107-112.

Walker, R. (1987). The effects of culture, environment, age, and musical training on choices of visual metaphors for sound. Perception and Psychophysics, 42, 491- 502.

Walker, R. (1992). Auditory-visual perception and musical behavior. In R. Colwell (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Music Teaching and Learning. New York: Schirmer.

Wheelwright, L. F. (1939). An Experimental Study of the Perceptibility and Spacing of Music Symbols. NY: Columbia University.