The purpose of this report is to convey information that I presented at a panel session at the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) annual meeting in Dallas in November 2001. The panel presentation, "Music Education and Performance Programs: Isolation or collaboration?," was organized by Karen Wolff, Dean of the School of Music at the University of Michigan. Panel members examined issues related to the current shortage of music teachers in public school music education.

My responsibility was to present data on the job market in college music. I prepared to answer the following questions: What has been the trend in the college job market for music vacancies based on data from the CMS Music Vacancy List since 1980? And, more specifically, what has been the trend for college jobs in music education?

Other members of this panel were Tom Lee, President of the American Federation of Musicians, and Carolyn Lindemann, Past President of MENC (the National Association for Music Education). Tom Lee offered statistical information on the job market among professional musicians. I will briefly discuss the presentations of these panel members and then share information that I gathered regarding music job vacancies in higher education.

It was no surprise to hear that of all jobs available for performing musicians, only a small percentage of these were full time. And there are many fewer jobs open every year than there are graduates looking for jobs. Lindemann shared that there is a great and growing shortage of music teachers in the public schools of the United States. Although there were roughly 7000 public school music teaching jobs open in June 2000, there were only approximately 3700 graduates with BM degrees in music education.

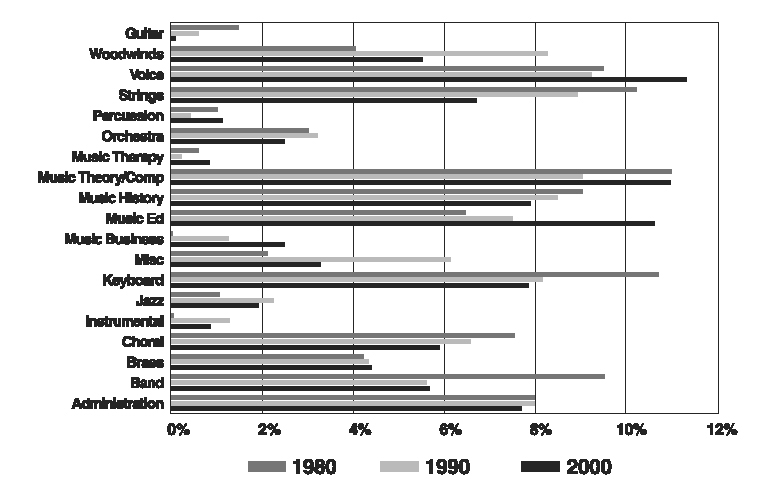

While there is a music teacher shortage in public schools, music education vacancies in higher education are growing as well. Based on data from the College Music Society music vacancy lists, music education positions have had the greatest growth compared to all other positions since 1980. The charts at the conclusion of this article highlight this growth. In these charts, comparisons of the percentages of job vacancies in the CMS vacancy list for the years 1980, 1990 and 2000 are made. Chart 1 shows percentages of job openings for all job listings in the CMS vacancy lists in 1980, 1990, and 2000.

Chart 1: Percentages of job vacancies in CMS?1980, 1990, and 2000

The trends from these data show that while the jobs in music theory and composition as well as voice have consistently held the highest percentage of all job openings, music education moved from the middle of the pack to near the top between 1980 and 2000. In 1980, the percentage of music vacancies for music education was 6.5% of all openings, while in 2000, this percentage jumped to 10.7%. In comparison, the percentage of openings that were in music theory and composition in 1980 were 11% as well as 11% in 2000.

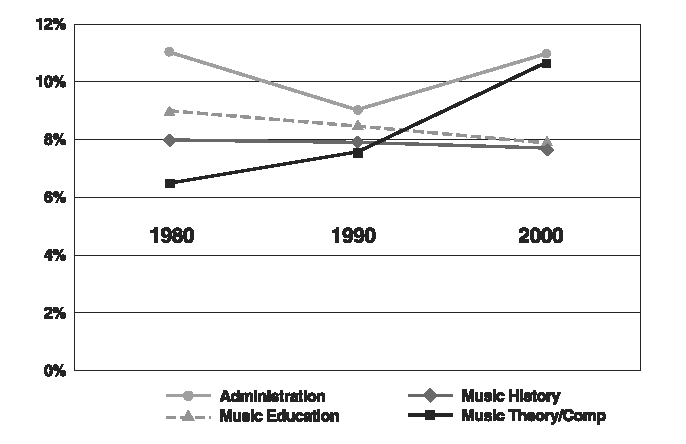

Charts 2, 3, and 4 isolate or combine data and compare growth of vacancies since 1980 in various positions. Chart 2 compares CMS vacancies in music education to those in music theory and composition, music history, and music administration. The rise in vacancies is the steadiest and most consistent in music education when compared to the others.

Chart 2: CMS vacancies grouped by Academic area, administration and music education?1980, 1990, and 2000

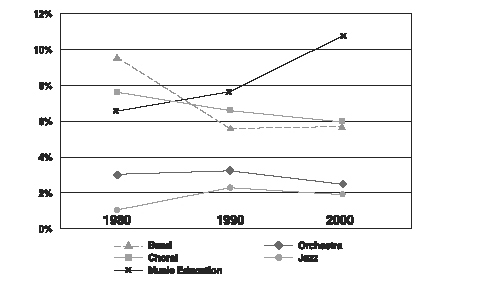

In chart 3, the vacancy openings in various ensemble teaching-conducting positions are compared to areas to music education in 1980, 1990, and 2000. Music education has a comparatively drastic increase over the 20-year period while the ensemble position vacancies have declined.

Chart 3: CMS vacancies grouped by ensemble area and music education?1980, 1990, and 2000

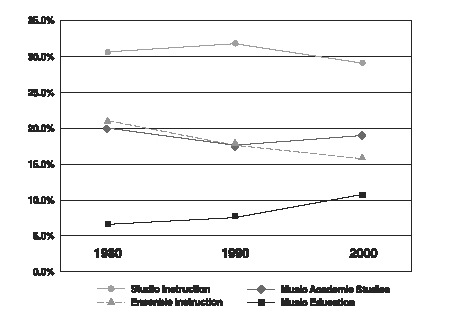

Chart 4 groups vacancies in the areas of studio instruction (brass, woodwind, and piano), ensemble instruction (band, orchestra, chorus, and jazz), and music academic studies (music history and literature, theory and composition) and compares these groupings to vacancies in music education. Again the rise in vacancies is most apparent and consistent in the area of music education.

Chart 4: CMS vacancies grouped by academic studies, ensemble instruction, studio instruction, and music education?1980, 1990, and 2000

The relative percentages of job openings in each of these areas roughly matches the doctoral degrees conferred in 1997-1998 according to statistics from the National Center for Educational Statistics (http://nces.ed.gov/). In 1997-1998, 79 doctoral degrees were granted in music education, 103 in music theory, composition, history and literature, and 302 in music performance areas. However, the greatest growth in doctoral degrees conferred between 1992 and 1998 is in performance (219 in 1992, 302 in 1998), while performance area vacancies (studio instruction and ensemble instruction) in higher education show the greatest decline during this decade (see chart 4). While music education vacancies have risen, the number of doctoral degrees in music education conferred between 1992 and 1998 has remained mostly unchanged (74 in 1992, 79 in 1998).

The problem in music education is that not only is there a need to train more music educators at the Baccalaureate level in order to fill the growing public school job vacancies, there is also a need to keep up with the growing number of job vacancies in higher education in order to prepare future K-12 music teachers. The shortage of K-12 music teachers coupled with the growing vacancies for music education positions in higher education, may eventually pose a severe problem. How can we lure more of the best and brightest public school music teachers into the higher education profession? And how might we lure more undergraduate students into music education? In part 2 of this report, I will pose possible answers to these questions.