Ensemble directors devote enormous attention to programming concerts.1 When selecting pieces and deciding on program order, consideration is given to musical and textual themes, cultural and historical origins, tempos, keys, forms, durations, and many other factors, in an effort to provide a well-planned and musically satisfying concert experience for the audience.2 Within the context of the musical rehearsal, directors also spend significant time and effort teaching their performers to communicate with the audience through the music.3 These efforts at interpretation seek to communicate implicitly with the audience, without overt action on the part of the director or ensemble members.

Yet a number of studies have shown that more overt forms of communication, such as program notes, lecture-recitals, and pre-concert talks, enhance an audience's enjoyment of a concert and enrich their musical understanding. Listeners who attended pre-concert talks, for instance, indicated an increased level of comfort as an audience member and a desire to attend future musical events as a result of the experience.4 A similar study, based on responses to an audience questionnaire for a series of narrated and non-narrated concerts, found that the variable of narration was significantly linked to style preference and musical satisfaction. Through random videotaping techniques, audiences at the narrated concerts were also shown to have greater time on task during the actual performances.5

Despite these findings and numerous articles advocating program notes and other measures to reach audiences,6 these practices seem to be relatively rare, particularly within the choral arena. A 2002 study found that less than 15% of secondary choral directors use written program notes in their concert programs. Directors cited a lack of time and training as reasons for not using written program notes.7 No studies were found that addressed how to give music education majors opportunities to practice these skills and none explored the benefits of increased knowledge about the concert repertoire for the performers involved.8

In response to the above findings, the authors of the following study developed an interdisciplinary project designed to teach student performers who were also music education majors how to write program notes. The study was motivated by a desire to connect learning among the various disciplines within the music curriculum, creating an opportunity for students to apply knowledge gained in other courses to their applied and ensemble study, while at the same time providing a model for interdisciplinary instruction that could be carried over into music programs in the secondary schools. It also sought to provide a more meaningful musical experience for both the audience and for the performers. The project had the following goals: a) to improve the students' writing ability, particularly the ability to write intelligently and succinctly about music; b) to enhance the performance experience by increasing knowledge about and interaction with the repertoire; c) to connect learning from a variety of disciplines required in the Bachelor of Music Education degree program (performance, music history, music theory, education, writing); and d) to instill a value for program notes as an educational tool for singers and audience members.

Project Design

Upper-level music education students enrolled in a choral methods course participated in a class project designed to meet the above goals.9 The eleven students knew from the outset of the course that they would write notes for a major choral-orchestral concert in which most of the students would perform. One performance would be given on campus; a second was slated for the Texas Music Educators Association Convention in San Antonio—both venues in which very large audiences would be in attendance. With the cooperation of the choral conductors, a music education and a music history professor (the authors of this study) guided the students in developing the program notes.

The Project—Step-by-Step Guidance

The first stage of the project was an in-class presentation about why and how to write program notes. It began with a discussion about the purpose of notes. The students themselves identified the following purposes: to educate the audience; to increase audience enjoyment; to educate the performers and enhance their performance of the music.

Next, information was given about how to write program notes. Students were advised to start by asking a series of questions, beginning with general ones such as: What do I want the audience to know about this piece? What should they listen for when they hear it? What is the most significant feature of this piece? Once those questions were considered, more specific questions about the "who, what, why, where, and when" of the music should be addressed. "What" questions could include what type of piece it is (a cantata, oratorio, etc.) as well as form. "Why" refers to the reason a piece was composed: was it for a special occasion or a specific performer, for example. "Where" questions would include a work's cultural context. Students were advised that they could choose not to include all of the above information in their final products, but that they should find the answers to these questions in order to have a well-rounded understanding of the work.

The next section of the in-class presentation dealt with another important question: What should the audience listen for? For choral pieces, this would include how the music relates to or expresses the text. Students were also encouraged to relate a piece and its music to other selections on the same program. Even if there is not an overall theme to the program, are the texts or the composers related somehow? Are there musical devices that recur? Making connections between pieces within the same concert helps give audience members a context in which to place the music.

Students were then given a series of writing tips, including keeping the audience's knowledge-level in mind and the importance of precise, concise language. Because musicians use a highly specialized vocabulary that can be an obstacle for general audience members, strategies for making program notes accessible to non-musicians were discussed. As a part of the presentation, students verbally generated examples of how to briefly define musical terms. The professors also gave examples of how to use similes or metaphors to bring points across (e.g., "it sounds like a sigh," "the violins wander off on their own").10 Employing active verbs and finding colorful adjectives were other recommendations. Students then rewrote several intentionally weak sample sentences in class in order to immediately apply these writing tips.

The in-class presentation concluded with a series of reminders: While there are many options when writing program notes, usually the piece itself will dictate what the writer will focus on or include; keep the main goal for writing program notes—to enhance the listener's experience—in mind at all times.

During the class meeting following the note-writing presentation, students participated in a program note "scavenger hunt." Sample program notes written by the music history professor were distributed to the class. To re-enforce the concepts from the presentation, students were asked to find examples of techniques that had been identified as important elements of a quality program note.

After the "scavenger hunt," students were given the full writing assignment. Students formed writing teams by selecting one piece from an upcoming choral-orchestral concert featuring Psalm 115 by Felix Mendelssohn, Schicksalslied by Johannes Brahms, and Te Deum in C major by Franz Joseph Haydn. For each piece, one group member was asked to write about the composer (biographical information); a second was to focus on the stylistic period and its cultural and historical influences; a third was asked to discuss the musical techniques employed in the piece; the fourth was assigned the connections between the text and the music. Thus, each student had a unique writing assignment.

Students had two weeks to research and write 500-word rough drafts which were then reviewed independently by the professors. Some drafts were "rougher" than others; several were quite polished. All of the drafts had passages that could be worded more simply. Despite the in-class presentation, most notes included musical terms that needed to be defined or reworded so that a lay person could readily understand them (e.g., hemiola). Organization was a problem in some. In general, those that focused on the composer's biography were more clearly organized. Connecting the biographical information to the piece in question, however, proved to be a challenge. One student, for example, wrote a clear and lively summary of Mendelssohn's life, but failed to mention Psalm 115.

Students received numerous recommendations from both professors on how to improve their work. The feedback ranged from very specific suggestions on how to reword some sentences to more general comments such as "awkward" and "explain." In some cases, the professors asked questions in order to elicit revisions (e.g., What should we listen for here? What about the Esterházys is relevant to this composition?). The strong points of the notes were also praised. Students then revised and resubmitted their notes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Revision example: Original sentences, suggestions and revisions

Rough Draft: Haydn employs an old Gregorian chant in the opening theme. First noticeable in the violins, the chorus confirms at its entrance the use of the eighth Psalm tone from the text's earlier days in the liturgy.

Suggestion by Professor 2: The chorus's entrance confirms? Can you make it clearer that this is the tune this text would have been chanted to and that the audience in Haydn's time would have recognized it?

Student's revision: Haydn employs an old Gregorian chant in the opening theme. First noticeable in the violins, the chorus confirms at its entrance the use of the eighth Psalm tone from the text's earlier days in the liturgy. Because the Psalm tone was sung regularly in Catholic services, the audiences in Haydn's day would have recognized the tune immediately.

The students' final copies were due nine days after they received the feedback on their rough drafts. The revisions resulted in individual notes that, for the most part, were complete and well-written; some were truly excellent and could have easily stood on their own. A few notes had good content but were poorly written. Not surprisingly, even though students focused on different aspects of the piece, notes about the same work contained some overlapping material.

Rather than selecting the best note for inclusion in the concert program, the supervising professors decided early on in the process to have students in each group consolidate their individual essays into a single group note. One reason for this decision was to give every student an incentive to do well on the project. It was clear from prior assignments in the class that some class members were substantially stronger writers than others. Had the project been set up as a competition, the excellent writers would have been inspired but the weaker writers would have conceded to the stronger. Another factor taken into consideration was that of modeling interdisciplinary collaboration for these music educators. By consolidating their individual notes into a composite essay, students would also gain the experience of working in a team, as is increasingly desirable in the educational arena.11

The success of the collaborative process varied by group. Two of the teams had usable, well-written material from every member. In these cases, each member of the group read aloud his or her note to the others. After expressing appreciation for the information found by the others, they deliberated seriously over which person's writing to include when there was overlapping content. The students in these groups were considerate and generous with each other and made sure that each person was represented in the final product. The completed notes were then reviewed by the faculty members for final comments and corrections.

The third team was less successful at collaborating. Of the three group members, one had written a relatively high quality note, while the other two notes were substantially weaker. Because of this disparity, it was more difficult to find something of quality and relevance from everyone to include. Moreover, this group was the least generous with each other—bordering on defensive. In the end, the faculty members chose to summarize for the group the "best" part of each person's note and then compile the final note themselves, using the students' material. While not ideal, this decision probably maintained friendships—or at least working relationships—among the class for the remainder of the semester.

Results

The program notes that resulted from the collaboration addressed musical devices, text-music relationships, and historical and biographical context—the same aspects that students were asked to address as individuals. The students successfully applied the style guidelines they gathered from the in-class presentation and exercises. (Figure 2 contains one of the published notes.)

Figure 2. Program note excerpt for Psalm 115 by Felix Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1809. Son of a wealthy banker and grandson of famous philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, Felix grew up in a world of tremendous intellectual sophistication. Like Mozart fifty years earlier, Mendelssohn was a child prodigy, given every opportunity to succeed. His parents actually hired an orchestra so their son's music could be heard.

Among the first generation of romantic composers, Mendelssohn is often referred to as a "classic romantic." His music emphasizes clarity and adheres to classical ideals. For example, Mendelssohn reflects the rhythmic and harmonic expressions of Handel, the imitative polyphony of Bach, and the musical textures of Mozart and Haydn. However, Mendelssohn also portrays a deep sense of Romanticism, by closely molding his music to express ideas evoked by words and phrases, as well as through forceful harmonic progressions.

Based on Psalm 115, the four distinct movements of Mendelssohn's Not Unto Us, O Lord pour out praise and adoration for God in a very powerful way. Mendelssohn brings focus to God by using the holy number three as a recurring symbol, utilizing triple meter, arpeggiating the accompaniment and moving the voice parts in thirds.

The fugue-like first movement is rhythmic and declamatory, like an emphatic proclamation: God, not us, receives glory and honor! The overall harmonic structure and rhythmic precision depict the idea that our God is a God of strength and order. Other nations should not question the might and greatness of God.

The second movement flows with lyricism. The text and music are full of hope that God the helper and redeemer will bless His people. Tenor and soprano soloists soar over the chorus, resembling angels sent to bring this hope to God's people.

The third movement reinforces the hope found in the second movement with assurance as a baritone solo proclaims that God will indeed bless His children. Corresponding to the text, the music is more declamatory, but the lyricism of the second movement is not lost.

The fourth movement begins with an emphatic chorale: The dead do not praise God, "but we who live today praise the Lord, our God, from this time forth and forever more." This exclamation echoes the majesty and triumph of the first movement, yet with warmer expression. The opening line of the Psalm returns following the chorale. Unlike the first movement, however, it is marked dolce (sweetly) and flows smoothly along in the minor key until the Picardy third on the last chord. With this, the cantata ends conveying a sense of thankfulness and praise to God for His goodness toward humankind.

Melanie Nelson

Erin Humphrey

Trevor Lee

Tricia Filippini

Each group's composite note appeared in the program for the October 15, 2002 performance of the Baylor Choral Union with the Baylor Symphony Orchestra and at the performance of the same program for the annual convention of the Texas Music Educators Association (TMEA) on February 14, 2003. The names of the student authors were listed at the conclusion of each note. A sentence at the end of the entire program acknowledged that the notes were "written by upper-level vocal music education students, under the supervision" of the two professors.

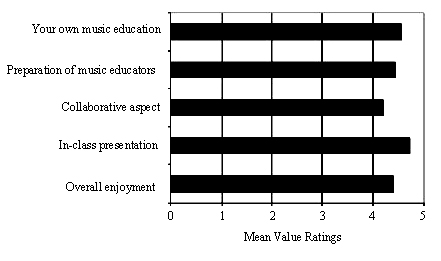

After the October 15th concert, the students who had participated in the project were given a survey which asked them to reflect on the project as a whole and the value of various aspects of the process—to their own music education, to their preparation as music educators, of the collaborative aspect, of the in-class presentation, and their overall enjoyment. Each question asked the students to rate their response on a scale from 1 to 5 with 5 being the highest. All responses were anonymous. Value ratings for each question were high, with mean scores ranging from 4.2 to 4.7 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Survey responses for participating student writers

Note. Participants (N = 11) rated the value of the project in various categories. Responses were rated from 1 (not valuable) to 5 (very valuable).

After each question, students had an opportunity to provide verbal comments. In terms of their own music education, those who sang in the concert reported that the project enhanced their performance experience. One said that the notes made the performance "more meaningful to me." Another wrote that "It was helpful for me to . . . know who, what, why it was written, etc. It gave me a better understanding of the piece as a whole." Another remarked that the project was "very important to my 'whole' education . . . good to apply my history and theory classes to my choir performance."

Concerning preparation for a career in music education, one stated that "This is something that I believe I'll use often as a music educator. . . . It is good to know all this stuff about the pieces we sing. . . . I can use the info I gain in researching for the notes . . . to share with the choir so they have a background of the music as well." "Music Educators need to become familiar with 'concise and descriptive . . . vocabulary'," wrote another, "It's always valuable to practice something you'll have to do in the future."

Not surprisingly, responses were mixed concerning the collaborative aspect of the project. Comments ranged from enthusiastic ("I thought the collaboration was great. It gave me the opportunity to see what everyone else's take was on the piece, what they wrote . . . putting it together and seeing the final outcome was fun") to disgruntled ("We didn't get to work as a team. . . . As a writer I am picky about my . . . compositions. The process of bringing together four or five different program notes to make one causes a writer to compromise his/her work"). Still, students recognized that collaborating, as one noted, "fostered teamwork instead of competition." "We were all able to share in the final product instead of one person 'winning,'" commented another.

Students thought that the instruction they received adequately prepared them to write program notes. One student, for example, said that the in-class presentation was "extremely helpful in knowing what to include and where to begin."

These remarks revealed that students recognized the value of program notes as an educational tool and that the process had helped them connect skills and information across classes. All students expressed pride in having their notes used for public and very prominent performances. "It was very enjoyable hearing others' input and ultimately seeing it in print on the program with our names," stated one student. Another commented, "I felt like I accomplished something."

The project also garnered positive responses from other students and faculty members. A student who sang in the performance "thought it was neat that students at Baylor wrote them" instead of a teacher or professional writer.12 A number of faculty members expressed appreciation that professors from different divisions (Music Education, Music History and Theory, and Ensembles) worked together on the project.13 In fact, after seeing the results of the project, one of the band directors planned to design a similar one for his conducting students.14

Reflections and Future Recommendations

In terms of educational benefits, the project fulfilled its intended goals. Through the instruction given in class, students increased their understanding of the purpose and content of program notes. The rough draft and revision sequence improved the students' writing abilities. Through the collaborative process, participants gained experience in editing and evaluating their work and the work of others. Students were also given a model for interdisciplinary teaching and learning, by having to relate knowledge from courses in music theory, music history, and applied study to their ensemble performance. Additionally, the positive response to the notes from other performers, music faculty, and general audience members helped the students to recognize the value of program notes as an educational tool.

For the student writers, knowing that the notes were going to appear in print in two high profile concert programs increased both the effort given to the project and the quality level of the resulting product. As one participant commented, "Always with an assignment there's an element of 'homework' that's not always enjoy[able], but it was neat to know that my portion . . . would be added to others and printed in a program . . . that was motivating." This study and others suggest that music teacher educators should develop more opportunities for student work to be showcased in "public" venues.15

The collaborative component had its pros and cons. On the positive side, by dividing the writing assignments into smaller segments, student writing was more focused and concise. Each writer was able make a unique contribution to the overall note, thereby rewarding the efforts of all of the participants. Students also had to evaluate the quality of their writing in comparison to others in their group. In addition, it gave participants tangible evidence of the multiple options available when creating notes. Group members were also challenged to consider opposing points of view. Members of one group, in particular, came up with very different interpretations of the same piece, causing them to rethink their initial interpretations of the music. On the negative side, the collaborative process also created some challenges that had to be overcome. The quality of writing varied greatly across the class and even within the groups. This disparity resulted in some difficulty making sure all writers had material in the final version of the notes. As mentioned earlier, the three groups varied in the level of cooperation shown among members during the editing process. One student felt that the collaborative component caused some of the writings to be compromised to the extent that the resulting note did not represent this student's particular interpretation of the musical material.

Many of the positive aspects of the collaboration (e.g., broadening students' thinking by encountering opposing points of view) carried with them accompanying negative features (compromising individual interpretations in order to blend into a single cohesive note). When using this type of assignment in the future, consideration will be given to these issues to determine if the benefits of collaboration outweigh the disadvantages. Methods to ensure that each group includes a strong writer will be weighed and perhaps implemented. Not only will the particular students involved in the process be taken into account, but the repertoire selected for the project will also play a crucial role in the decision. For the current project, the three works were of a substantial nature, incorporating orchestra, chorus, and soloists. If the project was repeated with shorter, more typical length choral pieces, a non-collaborative approach might be more sound. Such a concert would likely have more pieces, allowing each student to write a freestanding note, but steps could be taken to encourage continuity between the various notes in the program.

In future versions of this project, more could be done with the notes and the entire performing ensemble. The participants in this study were a small fraction of the actual number of performers (choral singers and orchestra members). Because the concert took place early in the fall semester, there was not time to share the notes during rehearsals while the pieces were being learned, as ideally would have been the case. This aspect should be developed further.

In order to help translate this experience from singers-as-authors to directors-as authors, or even directors-as-editors, this project should also be expanded into the secondary school setting. After successful experiences writing about their own performance repertoire, opportunities for music education majors to write program notes for high school and middle school choral concerts should be developed. Another option would be to have these future music educators serve as facilitators for high school or middle school choral students who write program notes for their own concerts. This last possibility would most closely approximate actual working conditions and would begin to develop these skills in an even younger generation of students.16 Bergee and Demorest's article "Developing Tomorrow's Music Teacher's Today" cites the ability of directors to "broaden and deepen the ensemble experience itself" with projects such as these as an important element in the cultivation of new music teachers.17

As a result of this project, audience members received informative program notes to supplement their concert experience; student performers collaborated to create a quality product that was well received by the larger musical community; and future music educators gained an appreciation for program notes and the importance of providing a broad artistic experience for their performers. The students who participated in the study are well-prepared and enthusiastic about including program notes in concert programs when they assume the responsibility of teaching music through performance ensembles.

WORKS CITED

Bergee, Martin and Steven Demorest. "Developing Tomorrow's Music Teachers Today." Music Educators Journal 89:4 (2003): 17-20.

Brunner, David. "Choral Program Design: Structure and Symmetry." Music Educators Journal 80:6 (1994): 46-49.

Christensen, James. "Targeting an Audience." The Instrumentalist 47 (Nov. 1992): 52-58.

Consortium of National Arts Education Associations. National Standards for Arts Education: What Every Young American Should Know and Be Able to Do in the Arts. Reston, Va.: Music Educators National Conference, 1994.

DiBlasio, Denis. "Connecting with the Crowd." Flute Talk 10 (1991): 13-16.

Funk, Gary. "Literature Forum—A Culturally Permeable Choral Curriculum: Programming for the Twenty-first Century." Choral Journal 34:9 (1994): 39-41.

Gillis, Glen H. "The Effects of Narrated Versus Non-Narrated Concert Performances on Audience Responses." Ph.D. diss., University of Missouri, Columbia, 1995.

Graves, Daniel H. "The Choral Conductor's Communication of Musical Interpretation." Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 1984.

Hall, Tom. "Make Program Notes Work Harder for You." The Voice of Chorus America 25:2 (2001): 23-25.

Henry, Michele. "Program Notes: Myriad Benefits for Audience and Choir." Choral Journal 43:5 (2002): 53-55.

_____. "Experiencing Contest Before It Counts: A Unique Collaboration Between the University and the Schools." [forthcoming]

Irvine, Denmar. Irvine's Writing About Music. Edited by Mark A. Radice. Third Edition Revised. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1999.

Mahlmann, John J. "Keith Lockhart on Reaching Audiences." Music Educators Journal 84:2 (Sept. 1997): 38-40.

Maus, Fred Everett. "Learning from 'Occasional' Writing." Repercussions 6:2 (1997): 5-23.

McCoy, Claire. "The Excitement of Collaboration." Music Educators Journal 87:1 (2000): 37-44.

McCoy, Martha. "What to Do Before the Downbeat." Music Educators Journal 69 (1983): 34-35.

Openshaw, Richard (1995). "The Relationships Among Choral Performance Quality, Choral Student Emotive and Aesthetic Perception, and Audience Reaction." Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1995.

Single, Nancy. "An Arts Outreach/Audience Development Program for Schools of Music in Higher Education." Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University, 1991.

Thoms, Hollis. "Nurturing Interest in Young Concertgoers." Music Educators Journal 80 (1994): 44-45.

Trame, Richard. "On Programs and Program Notes: An Inquiry." Choral Journal 25:1 (1984): 11-12.

1An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2003 meeting of the South Central Region of the College Music Society. The authors wish to thank the choral music education students who participated in this project.

2Articles for both choral and instrumental directors have focused on the intricacies of quality concert programming. See for example, David Brunner, "Choral Program Design: Structure and Symmetry," Music Educators Journal 80:6 (1994): 46-49; James Christensen, "Targeting an Audience," The Instrumentalist 47 (Nov. 1992): 52-58; Denis DiBlasio, "Connecting with the Crowd," Flute Talk 10 (1991): 13-16; Gary Funk, "Literature Forum—A Culturally Permeable Choral Curriculum: Programming for the Twenty-first Century," Choral Journal 34:9 (1994): 39-41; John J. Mahlmann, "Keith Lockhart on Reaching Audiences," Music Educators Journal 84:2 (Sept. 1997): 38-40.

3Daniel H. Graves, "The Choral Conductor's Communication of Musical Interpretation" (Ph.D. diss., University of Connecticut, 1984); Richard Openshaw, "The Relationships Among Choral Performance Quality, Choral Student Emotive and Aesthetic Perception, and Audience Reaction" (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1995).

4Nancy Single, "An Arts Outreach/Audience Development Program for Schools of Music in Higher Education" (Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University, 1991).

5Glen H. Gillis, "The Effects of Narrated Versus Non-Narrated Concert Performances on Audience Responses" (Ph.D. diss., University of Missouri, Columbia, 1995).

6Trame (1984), Hall (2001), and Henry (2002) specifically advocate the use of program notes and sharing oral information in choral concerts. Richard Trame, "On Programs and Program Notes: An Inquiry," Choral Journal 25:1 (1984): 11-12; Tom Hall, "Make Program Notes Work Harder for You," The Voice of Chorus America 25:2 (2001): 23-25; Michele Henry, "Program Notes: Myriad Benefits for Audience and Choir," Choral Journal 43:5 (2002): 53-55. See also Martha McCoy, "What to Do Before the Downbeat," Music Educators Journal 69 (1983): 34-35; Nancy Single, "An Arts Outreach/Audience Development Program for Schools of Music in Higher Education" (Ph.D. diss., Ohio State University, 1991); Hollis Thoms, "Nurturing Interest in Young Concertgoers," Music Educators Journal 80 (1994): 44-45.

7Others questioned whether pieces typically programmed for secondary-level choral concerts merited substantial discussion, beyond providing translations of pieces in foreign languages. Henry, "Program Notes: Myriad Benefits," 53-55.

8Maus gives some recommendations about how to write program notes, but his article focuses primarily on how they differ from standard academic writing and how writing reviews and notes changed his perceptions of the relationships between writers and listeners. Fred Everett Maus, "Learning from 'Occasional' Writing," Repercussions 6:2 (1997): 5-23.

9Although this project involved choral music education students, the project design could be applied to all student musicians regardless of their applied area.

10Maus and Irvine also discuss the importance of considering the audience and of using figurative language in reviews and in program notes. Maus, "Learning from 'Occasional' Writing," 6-8, 10-15; Denmar Irvine, Irvine's Writing About Music, ed. Mark A. Radice, Third Ed. Rev. (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1999), 174-175 and 182-184.

11Music Educators Journal devoted an entire issue (Vol. 87, no. 5 [March 2001]) to the topic of the interdisciplinary curriculum. Articles included results of research in interdisciplinary teaching and learning, advantages and disadvantages of collaborative learning, preserving artistic integrity in collaborations, and going beyond related materials to integration.

12Kimberly Wilson, graduate voice student, Baylor University, personal communication, October 28, 2002.

13Donald Bailey, personal communication, October 15, 2002; Lisa Maynard, personal communication, October 15, 2002; Barry Kraus, personal communication, October 17, 2003; James Bennighof, personal communication, January 28, 2003; David Music, personal communication, February 12, 2003; Jann Cosart, personal communication, February 12, 2003; Randall Bradley, personal communication, February 28, 2003.

14Barry Kraus, personal communication, October 17, 2003.

15See McCoy's "The Excitement of Collaboration" (2000) for a description of an interdisciplinary collaboration between music and other subject areas, involving university faculty and students and public school teachers and students. Claire McCoy, "The Excitement of Collaboration," Music Educators Journal 87:1 (2000): 37-44. Another example of a collaborative project that gave students an opportunity to work in a public venue will be discussed in Michele Henry's "Experiencing Contest Before It Counts: A Unique Collaboration Between the University and the Schools" [forthcoming].

16The National Standards for Music Education promote as educational goals "listening to, analyzing, and describing music" (NS 6), "understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts" (NS 8), and "understanding music in relation to history and culture" (NS 9), all of which can be addressed through activities such as this. Consortium of National Arts Education Associations, National Standards for Arts Education: What Every Young American Should Know and Be Able to Do in the Arts (Reston, Va.: Music Educators National Conference, 1994), pages 61-63 and 105-110 in particular.

17They further argue that "Students need to learn more about music as an art and craft. Ensemble rehearsals are ideal occasions for students to analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and create. Furthermore, opportunities are there to learn more about the historical and cultural backgrounds of the music being rehearsed. These kinds of activities, regularly incorporated into high school rehearsals, might lead students to see the 'academic' aspects of music—history and theory, for example—as indispensable components of performing experiences." Martin Bergee and Steven Demorest, "Developing Tomorrow's Music Teachers Today," Music Educators Journal 89:4 (2003): 20.