Toward Analytic Reconciliation of Outer Form, Harmonic Prolongation and Function

Written by Kevin J. Swinden

Symposium Volume 45

Grieg's "The Song of Siri Dale" is a G minor setting in Grieg's op. 66 collection of Norwegian Folk Songs for solo piano. As one might expect of a folk song, Siri Dale's melody expresses a traditional tonal statement, regular in its metric scheme.1 Grieg's harmonic setting, however, cuts across the natural divisions suggested by the melody, creating interesting formal problems to reconcile. In this study, I shall begin by highlighting the structural curiosities by using established analytic techniques, even if principally designed for analysis of Classic-era music. After applying the different techniques independently, I shall try to reconcile them, and attempt to isolate the assumptions of each that lead to apparent contradictions between the findings. It is my intent to show how a pluralistic approach to analysis might be applied so that each method informs the others.2 In so doing, I hope to generate a balanced and unified view in a finished product that reconciles these differences. These explorations might lead to a synthetic approach that penetrates the music of the late nineteenth century more efficiently.

Commentators are consistent in their view that Grieg's folk-song settings represent some of his finest work. As a young admirer of Mozart, Chopin and Schumann, a student of E.F. Richter, Hauptmann, and Moscheles, and an inspiration to Debussy and Delius, Edvard Grieg maintains a Classic/Romantic pedigree that is beyond reproach. With such a historical position, perhaps it is not surprising that his music can resist traditional pigeonholes. His particular synthesis of the old and the new can make for fascinating case studies in a variety of analytic approaches.

Grieg began work on the op. 66 collection in 1896; it was published in 1897. In this collection, Grieg's declared intent was to set these songs while exploring a rich harmonic vocabulary born of his nationalistic imagination. In notes to his American biographer, Henry Finck, Grieg writes:

The realm of harmonies was always my dream-world, and the relationship between my harmonic idiom and Norwegian folk-music was a mystery to myself. I have discovered that the dark profundities of our folksongs contain in all their richness unsuspected harmonic possibilities. In my folksong arrangements (op. 66) and similar works I have attempted to give expression to my perception of the hidden harmonies of our folk-music. To this end, I have been particularly attracted towards the use of chromatic progressions in the harmonic texture.3

While it is generally good advice to read such broad self-analytic claims with skepticism, it is widely accepted that in the later settings of traditional music, including the opp. 66, 72 and 74 collections of folk songs, peasant dances, and psalms respectively, Grieg achieved a mature and distinctive harmonic style. Grieg's reference to the "hidden harmonies" of Norwegian folk music is particularly mysterious; the extent to which the folk idiom may be responsible for certain harmonic structures shall only be touched upon briefly in this essay, but the comment certainly invites further exploration.

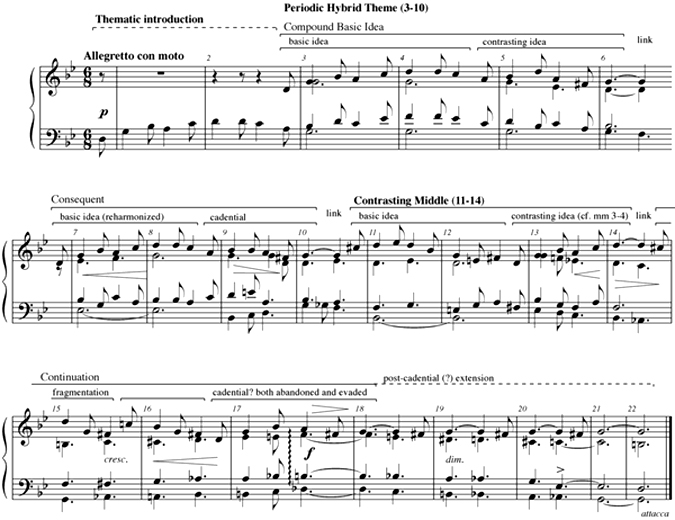

A Reading based on Caplin's Theory of Classical Form

Caplin's theory of Classical form lends an excellent orientation to the outer form of the piece.4 The setting is best described as a small binary form without repeats. (See example 1) The left-hand melody presents the basic idea of the opening theme without harmonic support. When the melody is restated in the right hand in m. 3, with harmonic support and followed by a proper melodic response, the opening measures are recognized as a thematic introduction.

Example 1.

The A section spans mm. 3 through 10, and consists of a hybrid theme that is closer in design to a period than a sentence. A four-bar compound basic idea appears over a tonic pedal, lacking cadential arrival. This is answered with a consequent phrase. The basic idea is restated, fulfilling a condition of expository function, but is reharmonized over a flat-submediant pedal. A cadential progression brings a perfect authentic cadence in G minor on the downbeat of m. 10.

A one-chord link introduces the dominant of the relative major and serves as transition into the B section of the Small Binary, beginning in that key. The B section begins with contrasting middle material that resembles another compound basic idea. A new basic idea is stated above a  pedal (mm. 11-12), followed by a contrasting idea (mm. 13-14) that is derived from the basic idea of the A section (mm. 3-4). The phrase momentarily stops with a contrapuntal cadence in m. 14 in the key of

pedal (mm. 11-12), followed by a contrasting idea (mm. 13-14) that is derived from the basic idea of the A section (mm. 3-4). The phrase momentarily stops with a contrapuntal cadence in m. 14 in the key of  . A single chord serves as a retransition to a G tonality, and the beginning of a continuation phrase. The continuation features fragmentation (one-bar fragments) followed by two bars that have the properties of a cadential idea without its full realization. The friction generated between the tonal folk-melody and its treatment creates the problems that need reconciling at this moment. The accompanying voices that support the fragmentation are based on a model-sequence technique: chromatically rising dominant-seventh/augmented-sixth sonorities support a melody with a descending profile. The melody continues, with its strongly implied G minor perfect authentic cadence, while the harmonic sequence carries on without regard for this melodic implication. At the moment that one would expect the penultimate dominant, the bass line remains on a notated

. A single chord serves as a retransition to a G tonality, and the beginning of a continuation phrase. The continuation features fragmentation (one-bar fragments) followed by two bars that have the properties of a cadential idea without its full realization. The friction generated between the tonal folk-melody and its treatment creates the problems that need reconciling at this moment. The accompanying voices that support the fragmentation are based on a model-sequence technique: chromatically rising dominant-seventh/augmented-sixth sonorities support a melody with a descending profile. The melody continues, with its strongly implied G minor perfect authentic cadence, while the harmonic sequence carries on without regard for this melodic implication. At the moment that one would expect the penultimate dominant, the bass line remains on a notated  (

( of G minor) and thus might constitute an abandoned cadence.5 At the moment that one would expect the cadential tonic,

of G minor) and thus might constitute an abandoned cadence.5 At the moment that one would expect the cadential tonic,  is tied across the barline, and the abandoned cadence is thus evaded. Example 2 suggests a possible rewritten cadence at this point.

is tied across the barline, and the abandoned cadence is thus evaded. Example 2 suggests a possible rewritten cadence at this point.

Example 2.

Whereas Grieg provides an ending that responds to the progressive dynamic curve of mm. 15 to 17 with a balancing recessive dynamic, the "pseudo-Grieg" rewritten version utterly fails in that regard. In the authentic version, the accompanying voices return whence they came, chromatically sliding down dominant-seventh/augmented-sixth sonorities, supporting a tonic prolongation in the melody. Melodically and structurally, the last four bars sound and feel like a post-cadential extension, but of a cadence that never materialized. Instead of a cadence, Grieg positions the apex of the B section's dynamic curve at the expected point of cadential arrival.

The boundaries of this "Caplinian" formal reading have a certain degree of contentiousness. I confess that the proposition of a cadential idea without even a semblance of harmonic confirmation followed by a post-cadential extension might be construed as a rather cavalier analytic approach. Nevertheless, the rhetoric of this division is tangible, and there is clearly an element of the form that is captured by the cavalier description. The miniature is marked to continue to the next folk song in the set, attacca. From the Caplinian formal perspective, this does not seem to be a critical aspect of the work's structure, as it is possible to read the miniature as a tonally closed work. Despite the lack of strong cadence, there is still formal and rhetorical balance in the work as a self-standing miniature. However, as we shall see later, voice leading and functional analyses will challenge this view.

A Schenkerian Reading

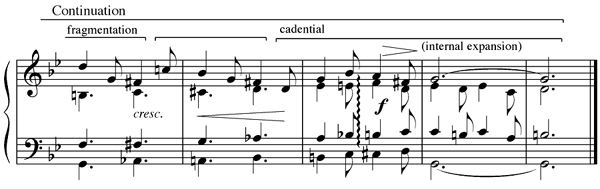

From a Schenkerian perspective, a  -line engenders a reasonable analysis. (See example 3)

-line engenders a reasonable analysis. (See example 3)

Example 3.

A gapped ascent (marked as motive x in the graph) approaches a Kopfton  in the first phrase. Over the course of the opening compound basic idea, a 5-span is supported by inner-voice parallel sixths, all over a tonic pedal. The pitch

in the first phrase. Over the course of the opening compound basic idea, a 5-span is supported by inner-voice parallel sixths, all over a tonic pedal. The pitch  is retained from the compound basic idea of the A section and is transformed into a dissonance over

is retained from the compound basic idea of the A section and is transformed into a dissonance over  , corresponding to mm. 7-8 in the score. The dissonant

, corresponding to mm. 7-8 in the score. The dissonant  resolves to

resolves to  which is a consonant sixth over the flat-submediant pedal tone; the remainder of the descent (

which is a consonant sixth over the flat-submediant pedal tone; the remainder of the descent ( -

- -

- ) is an unremarkable Schenkerian gesture. A deeper structure easily recognizes

) is an unremarkable Schenkerian gesture. A deeper structure easily recognizes  supporting a structural iv6 harmony. In the A section as a whole, the Schenkerian reading seems to cast only one shadow across Caplin's formal theory. In the consequent phrase, the Caplinian reading has the cadential idea (mm. 9-10) supported by a complete cadential progression, and would seem to imply a closed harmonic entity in the form T-S-D-T (i6-IV

supporting a structural iv6 harmony. In the A section as a whole, the Schenkerian reading seems to cast only one shadow across Caplin's formal theory. In the consequent phrase, the Caplinian reading has the cadential idea (mm. 9-10) supported by a complete cadential progression, and would seem to imply a closed harmonic entity in the form T-S-D-T (i6-IV -V4-3-i). The Schenkerian reading, privileging authentic tonal motion above the two-bar normative proportion in the outer form, recognizes that the cadential progression is not, in fact, a self-contained structural unit. Rather, the progression from i6-IV

-V4-3-i). The Schenkerian reading, privileging authentic tonal motion above the two-bar normative proportion in the outer form, recognizes that the cadential progression is not, in fact, a self-contained structural unit. Rather, the progression from i6-IV constitutes a harmonic interpolation between the bass Stufen

constitutes a harmonic interpolation between the bass Stufen  and

and  . From this perspective, it might be appropriate to reevaluate the Caplinian analysis of the consequent phrase (mm. 7-10) as an incomplete expanded cadential progression (ECP)—incomplete for missing the initial tonic.6 The difference between the two readings reduces to the interpretation of the structural hierarchy of the i6 chord in m. 9. In the first reading (in the style of Caplin), the i6 chord initiates a two-bar cadential idea, and might be understood as a plagal resolution of the prolonged iv6 harmony in mm. 7-8. In the Schenkerian reading, the i6 chord is not recognized as a Stufe at all, but rather, it embellishes the motion from iv6 (mm. 7-8) to V (m. 9, beat 2) and provides consonant support for

. From this perspective, it might be appropriate to reevaluate the Caplinian analysis of the consequent phrase (mm. 7-10) as an incomplete expanded cadential progression (ECP)—incomplete for missing the initial tonic.6 The difference between the two readings reduces to the interpretation of the structural hierarchy of the i6 chord in m. 9. In the first reading (in the style of Caplin), the i6 chord initiates a two-bar cadential idea, and might be understood as a plagal resolution of the prolonged iv6 harmony in mm. 7-8. In the Schenkerian reading, the i6 chord is not recognized as a Stufe at all, but rather, it embellishes the motion from iv6 (mm. 7-8) to V (m. 9, beat 2) and provides consonant support for  in the Urlinie. If one chooses to be so fussy on this small point, and wishes to modify the first reading in light of this interpretation, the result would be that instead of a four-bar phrase comprised of two, two-bar ideas (the repetition of the basic idea followed by a two-bar cadential idea), mm. 7-10 might be understood as a cadential phrase. While mm. 7-10 has the melodic trappings of a consequent phrase, the Schenkerian reading suggests that from a harmonic perspective, it is a four-bar cadential phrase. This reevaluation is not critical, and the original analysis survives the critique; indeed, to correct one reading exclusively in favor of the other might seem capricious. Nevertheless, the Schenkerian reading implies a different structural hierarchy within the consequent phrase. I shall leave this question open for the time being and return to it when the three analytic methodologies considered are reconciled in the final section of the essay.

in the Urlinie. If one chooses to be so fussy on this small point, and wishes to modify the first reading in light of this interpretation, the result would be that instead of a four-bar phrase comprised of two, two-bar ideas (the repetition of the basic idea followed by a two-bar cadential idea), mm. 7-10 might be understood as a cadential phrase. While mm. 7-10 has the melodic trappings of a consequent phrase, the Schenkerian reading suggests that from a harmonic perspective, it is a four-bar cadential phrase. This reevaluation is not critical, and the original analysis survives the critique; indeed, to correct one reading exclusively in favor of the other might seem capricious. Nevertheless, the Schenkerian reading implies a different structural hierarchy within the consequent phrase. I shall leave this question open for the time being and return to it when the three analytic methodologies considered are reconciled in the final section of the essay.

The B section begins in the relative major, and immediately reestablishes the Kopfton  as consonant. The section is based on an arpeggio figure moving to an inner voice, which outlines a G minor triad, all while

as consonant. The section is based on an arpeggio figure moving to an inner voice, which outlines a G minor triad, all while  is retained as the upper voice. Motive x returns in the closing gesture of this passage, with its strongest tonal support. Each time the melodic motive has appeared, it has been supported by a new harmonic variation. In the first instance, inner-voice parallel sixths support the motive over a tonic pedal. The second instance features inner-voice voice-exchange figures. In this third instance, it is part of structural contrapuntal motion directed toward temporary tonal closure in

is retained as the upper voice. Motive x returns in the closing gesture of this passage, with its strongest tonal support. Each time the melodic motive has appeared, it has been supported by a new harmonic variation. In the first instance, inner-voice parallel sixths support the motive over a tonic pedal. The second instance features inner-voice voice-exchange figures. In this third instance, it is part of structural contrapuntal motion directed toward temporary tonal closure in  .

.

The final phrase begins with fragmented melodic material, and is charged with striking harmonic relationships over a bass line that ascends chromatically from  to

to  . The ascent elides the basic idea into the final cadential idea, and

. The ascent elides the basic idea into the final cadential idea, and  in the bass arrives at the strongest moment of melodic arrival on

in the bass arrives at the strongest moment of melodic arrival on  . Consonant support is found for

. Consonant support is found for  and

and  in the ascending chromatic scale. When

in the ascending chromatic scale. When  resolves to

resolves to  in the melody, the bass

in the melody, the bass  is sustained, and proceeds to descend chromatically from

is sustained, and proceeds to descend chromatically from  to

to  . The descent is based on a descending 7-6 chromatic sequence that supports a post-cadential extension and melodic stasis (

. The descent is based on a descending 7-6 chromatic sequence that supports a post-cadential extension and melodic stasis ( -

- -

- foreground neighbor figures). The most problematic aspect of the reading is clearly the invocation of

foreground neighbor figures). The most problematic aspect of the reading is clearly the invocation of  supporting

supporting  . For

. For  to substitute for V, we are obligated in Schenker's theory to recognize the voice-leading origin of

to substitute for V, we are obligated in Schenker's theory to recognize the voice-leading origin of  in V through harmonic elision. As shown in example 4,

in V through harmonic elision. As shown in example 4,  has its origin in the elision of an applied diminished seventh chord of V with the dominant; the continuation (summarized in the example) delays the tonic support through descending chromatic passing tones. In this interpretation, we recognize that Grieg's notated

has its origin in the elision of an applied diminished seventh chord of V with the dominant; the continuation (summarized in the example) delays the tonic support through descending chromatic passing tones. In this interpretation, we recognize that Grieg's notated  in the bass is an elision of

in the bass is an elision of  resolving to

resolving to  . When tied into the descending chromatic passing tones, Grieg adopts the

. When tied into the descending chromatic passing tones, Grieg adopts the  spelling, perhaps for notational clarity. However, it is not a foregone conclusion that

spelling, perhaps for notational clarity. However, it is not a foregone conclusion that  and

and  are interchangeable symbols in a Stufen-theory.7 Since the melody has the only possible

are interchangeable symbols in a Stufen-theory.7 Since the melody has the only possible  to represent the tonal descent and structural cadence, the tonal expectation demands the symbol

to represent the tonal descent and structural cadence, the tonal expectation demands the symbol  . Elision suggests that the real function of the pitch (upon approach) might be

. Elision suggests that the real function of the pitch (upon approach) might be  , hence a

, hence a  Stufe. Despite this, I have allowed the deeper structural significance of the Urlinie

Stufe. Despite this, I have allowed the deeper structural significance of the Urlinie  to sway this analysis toward

to sway this analysis toward  , although I confess that the reading takes liberties with Schenker's theory.

, although I confess that the reading takes liberties with Schenker's theory.

Example 4.

The liberal Schenkerian perspective reveals some interesting aspects of the work, if I may be indulged the dissonant  /

/ in the Ursatz. My primary motivation was to respond to the clearly articulated melodic closure, and to show how the harmonic plan supports this closure, even if in a non-traditional way. The most interesting chromatic material, however, appears in the graph as a series of undifferentiated passing tones ascending, then descending, isolating the individual pitches necessary to provide the required consonant support for the Urlinie descent. Clearly this analysis models the contrapuntal voice leading, but it does not tell us anything about the functional details through that most interesting passage. In order to understand how Grieg has successfully supported the dominant

in the Ursatz. My primary motivation was to respond to the clearly articulated melodic closure, and to show how the harmonic plan supports this closure, even if in a non-traditional way. The most interesting chromatic material, however, appears in the graph as a series of undifferentiated passing tones ascending, then descending, isolating the individual pitches necessary to provide the required consonant support for the Urlinie descent. Clearly this analysis models the contrapuntal voice leading, but it does not tell us anything about the functional details through that most interesting passage. In order to understand how Grieg has successfully supported the dominant  with

with  in the bass, we must rely on an explanation that requires pitches that are not literally in the score (elision). While this explanatory technique has precedent and strong support in the Schenkerian literature, it is less convincing than an analysis that requires no such accommodation. This is also the same passage that was the cause for apology in the Caplin-inspired reading of the form offered above. Regardless, there are clearly structural issues involved in either case that have yet to be reconciled. Neither of these readings is offered here as a straw man; each attempts to be the very best possible reading according to the assumptions of the respective analytic practices. However, any theoretical assumption will create analytical biases. While these biases are not bad things, they need to be acknowledged when considering alternatives.

in the bass, we must rely on an explanation that requires pitches that are not literally in the score (elision). While this explanatory technique has precedent and strong support in the Schenkerian literature, it is less convincing than an analysis that requires no such accommodation. This is also the same passage that was the cause for apology in the Caplin-inspired reading of the form offered above. Regardless, there are clearly structural issues involved in either case that have yet to be reconciled. Neither of these readings is offered here as a straw man; each attempts to be the very best possible reading according to the assumptions of the respective analytic practices. However, any theoretical assumption will create analytical biases. While these biases are not bad things, they need to be acknowledged when considering alternatives.

A Functional Reading

Most of this piece is reasonably straightforward from a functional perspective, and a close reading would not elucidate much more than the Schenkerian reading already offered. In the following section, I concentrate only on the highly chromatic conclusion of the work that has been the source of the structural and formal concerns mentioned above.

Various harmony textbooks have explained passages such as mm. 14 through 23 with descriptive terms, citing a combination of contrary motion in essential voices, one or both of which is coupled with parallel motion or harmonic filler in the other voices.8 The advice offered amounts to abandoning attempts at Roman numeral analysis for the passage. The moment is interpreted without harmonic function to speak of, save for the function indicated at the endpoints of the passage, or those chords that happen to have a recognizable Roman numeral along the way. Since Roman numerals are the typical filter for harmonic function, the advice and rationale are well paired. The Schenkerian reading is in agreement with this advice, casting the passage as a series of passing tones and finding consonant intervals to support the expected Urlinie descent.

There are several counter-arguments that one might advance to the preceding advice. From the perspective of the Schenkerian reading of the piece, the advice offered suggests that a purple patch undergirds the entire Urlinie descent. Does this mean that the Urlinie lacks functional support, despite having hypothesized consonant contrapuntal support? (What does that mean?) Is the entire Urlinie descent an extended "unsupported stretch?" Is the music defective? (This would be an odd conclusion to reach that would purport to judge Grieg by the standards of a theory that takes the high Classic era as a paradigm.) Is the analytic tool defective? (Again, certainly not. It is not appropriate to criticize a primarily Classical tool for failing to elucidate a decidedly non-Classical moment in the work.)

Is the textbook advice perhaps founded on a faulty supposition? For those who subscribe to theories of harmonic function, it is accepted that Western music is functional, and that harmonic function is something that can be described, understood, and perceived. Analytic convention dictates that we identify sonorities with Roman numerals. These symbols indicate the pitch content of a collection in relation to a defined tonic.9 Roman numerals are then understood to belong to one of several larger categories of harmonic function; sometimes a particular context allows a single Roman numeral to belong to more than one functional category. This last statement may seem like an innocent step in the chain, but it has a critical implication. By ascribing harmonic function to Roman numerals, we assume that harmonic function resides in chords, reckoned as primarily diatonic tertian sonorities. That assumption is questionable, and indeed has been forcefully challenged before.10

When Harrison (1994) suggests that harmonic function might reside in the scale steps themselves rather than in chords, he opens the door to the possibility that harmonic function may be described, understood, and perceived, even if the succession of Roman numerals departs from conventional patterns. Thus, the argument "when a succession of Roman numerals does not make sense, the music is non-functional" is flawed. It is an argument that is predicated on the assumption that Roman numerals are the sole signifiers for harmonic function. This argument is thus unnecessarily restrictive to our functional understanding, placing the analytic theory before the music.

Harrison may have gone one step too far in his separation of function from chord: to address the faulty equation of chord with function, chords are replaced with scale steps outright. Each scale step is independent and vies for prominence. Scale steps interact with one another to amplify, compete with, or undermine other scale steps. While each scale step does not abandon its multiple potential, in the end, one holds sway over a progression. In contrast, I find that principles of diatonic position finding suggest that in certain combinations, small collections of scale steps abandon their multiple functional potentials in favor of a single allegiance. However, in highly chromatic contexts, more than one such pair might simultaneously suggest two functional allegiances, and that this difference need not be resolved. The character of the harmonic function expressed becomes more complex, and indeed, perhaps even plural.11

Although it makes a strange bedfellow, my view is in line with some aspects of Schenkerian thinking. In Schenkerian practice, only chords that engender prolongation are given the privileged status of a harmony (Stufe); all other activity is governed by principles of counterpoint. Cohn points out that even all Stufen in an analysis are ultimately a product of counterpoint, and that in Schenker's argument, the tonic "Chord of Nature" is the one and only true "harmony."12 Without the demand for harmonic fusion at any particular contrapuntal moment, it is quite reasonable to suggest that a musical simultaneity might represent the happenstance convergence of counterpoint that is pointing (for the moment) in two different directions. That is ultimately the same claim as a view of functional plurality: a moment (often poignant) is functionally charged in two directions.

Therefore, I have considerable difficulty with advice that suggests we give up on functional analysis when the Roman numeral analysis gets rough. If voice leading is meaningful at all, it is because it responds to or thwarts tonal gravities in interesting and sometimes surprising ways, yet it provides enough semblance of tonal anchor that we accept the music as coherent. Where there is no counterpoint to speak of and an obscure tonal context (planing in Debussy, perhaps) then I begin to accept an argument that harmonic function may be suspended. But where there are independent voices, i.e., counterpoint, there is, to my ear at least, harmonic function.

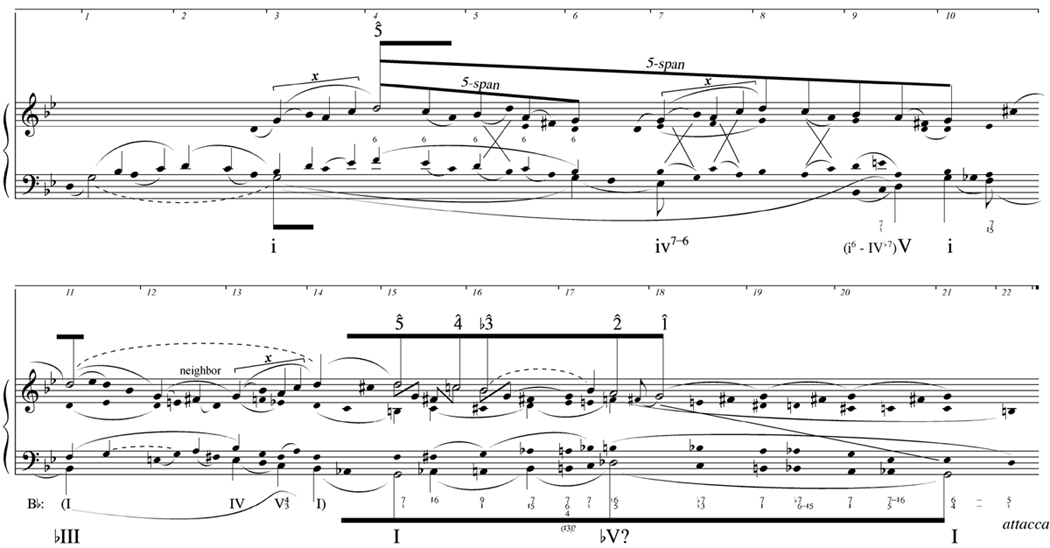

The following functional analysis of mm. 14 through 23 will attempt to uncover the nature of the harmonic function present that supports the hypothesized Urlinie descent of the Schenkerian reading. Voice-leading graphs and analyses of harmonic function are not mutually exclusive. In fact, these perspectives normally conform, obviating the need for a detailed investigation such as this. But, when different analyses point to different important moments, functional analysis can be quite illuminating.

The Schenkerian argument shows that the downbeat of m. 15 functions as the return of the home key tonic. However, the chord is also charged with an element of secondary dominant function that points toward C. The linking chord that connects the  major temporary tonic in m. 14 to the downbeat of m. 15 is a DØ

major temporary tonic in m. 14 to the downbeat of m. 15 is a DØ harmony. From the perspective of returning to G minor, the bass line

harmony. From the perspective of returning to G minor, the bass line  -

- is coupled with

is coupled with  -

- in the alto, which together generate a strong subdominant-to-tonic functional discharge. The soprano neighbor figure

in the alto, which together generate a strong subdominant-to-tonic functional discharge. The soprano neighbor figure  -

- -

- weakens the common-tone connection that might suggest a shift from dominant base to tonic associate (

weakens the common-tone connection that might suggest a shift from dominant base to tonic associate ( -

- , a context that undermines the functional potential of the dominant base) and amplifies the subdominant aspect of the resolution with the

, a context that undermines the functional potential of the dominant base) and amplifies the subdominant aspect of the resolution with the  -

- motion.13 While these features strongly charge the G chord with tonic function, the presence of f held as a common-tone in the tenor alters the functional attitude of the resolution. Rather than reading a modal dominant discharging to a tonic G (vØ

motion.13 While these features strongly charge the G chord with tonic function, the presence of f held as a common-tone in the tenor alters the functional attitude of the resolution. Rather than reading a modal dominant discharging to a tonic G (vØ -I

-I ), the harmony is more easily understood as a iiØ

), the harmony is more easily understood as a iiØ -V7 progression in the key of C.14 Thus, the G harmony that is recovered, coinciding with the last phrase of the tune, serves as both a recovery of tonic and as a structural arrival on the dominant of C.

-V7 progression in the key of C.14 Thus, the G harmony that is recovered, coinciding with the last phrase of the tune, serves as both a recovery of tonic and as a structural arrival on the dominant of C.

Rather than resolving directly into C, Grieg resolves the G7 chord deceptively to the Leittonwechselklang of the expected C minor tonic, an incomplete A chord. However, it is significant that the A

chord. However, it is significant that the A chord lacks its fifth,

chord lacks its fifth,  , which would be the tonic agent of the thwarted C minor triad. Without the tonic agent (

, which would be the tonic agent of the thwarted C minor triad. Without the tonic agent ( ), only the base (

), only the base ( ) of the expected tonic function is present in the alto voice, and thus tonic function is undermined. Instead, the progression is a dominant-to-subdominant (regressive) functional discharge. (See example 5) In functional graphs, triangular note heads indicate functional agency,15 and square note heads indicate functional bases. As shown in example 5, b is the dominant agent that resolves upward to the subdominant agent in parallel motion to their respective bases. Although the harmonic pattern established suggests that the G7 chord might rise sequentially by half-step, these harmonies interact with a melody firmly grounded in a tonic-dominant alternation in G minor. Thus, where

) of the expected tonic function is present in the alto voice, and thus tonic function is undermined. Instead, the progression is a dominant-to-subdominant (regressive) functional discharge. (See example 5) In functional graphs, triangular note heads indicate functional agency,15 and square note heads indicate functional bases. As shown in example 5, b is the dominant agent that resolves upward to the subdominant agent in parallel motion to their respective bases. Although the harmonic pattern established suggests that the G7 chord might rise sequentially by half-step, these harmonies interact with a melody firmly grounded in a tonic-dominant alternation in G minor. Thus, where  might be expected in the second chord,

might be expected in the second chord,  is used in its place. The

is used in its place. The  supports the mutation to dominant function, and amplifies the second dominant-to-subdominant functional discharge (dominant agent to subdominant associate). This subsequent

supports the mutation to dominant function, and amplifies the second dominant-to-subdominant functional discharge (dominant agent to subdominant associate). This subsequent  to G resolution is not shown as a dominant-agent-to-tonic-base discharge because the other accompaniment pitches (bass and alto) in the third harmony cannot support a tonic interpretation.

to G resolution is not shown as a dominant-agent-to-tonic-base discharge because the other accompaniment pitches (bass and alto) in the third harmony cannot support a tonic interpretation.

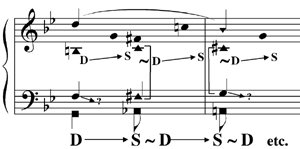

Example 5.

The pattern continues through the remainder of the ascending sequence to the second beat of m. 17. The final chord of the pattern is built on  where Grieg has, for only the second time in the sequence, spelled the tenor voice as an augmented sixth from the bass (

where Grieg has, for only the second time in the sequence, spelled the tenor voice as an augmented sixth from the bass ( -

- ) rather than a minor seventh. This augmented sixth interval points toward C in the strongest possible way; when the a' in the soprano moves to g' in m. 18, the chord becomes a French-sixth that demands a resolution on C. A dominant augmented-sixth that points toward

) rather than a minor seventh. This augmented sixth interval points toward C in the strongest possible way; when the a' in the soprano moves to g' in m. 18, the chord becomes a French-sixth that demands a resolution on C. A dominant augmented-sixth that points toward  , as this one does, is most unusual. In fact, this harmony is an ideal conclusion to the ascending sequence. Recall that this sequence pattern was initiated by a G7 harmony that at once fulfilled the necessary return to a G tonality and also bore a V/iv function that resolved deceptively. The endpoint of this prolongation returns to a chromatic dominant of iv that will, in fact, resolve to a version of the subdominant on the second beat of m. 18. Thus, at a structural level, the ascending sequence is a prolongation of a dominant of the subdominant, and the interior is charged with an accumulation of retrogressive dominant function (dominant-to-subdominant gestures). The unresolved sevenths throughout the passage contribute to the sense of retrogression, as the dissonances are denied an authentic resolution.

, as this one does, is most unusual. In fact, this harmony is an ideal conclusion to the ascending sequence. Recall that this sequence pattern was initiated by a G7 harmony that at once fulfilled the necessary return to a G tonality and also bore a V/iv function that resolved deceptively. The endpoint of this prolongation returns to a chromatic dominant of iv that will, in fact, resolve to a version of the subdominant on the second beat of m. 18. Thus, at a structural level, the ascending sequence is a prolongation of a dominant of the subdominant, and the interior is charged with an accumulation of retrogressive dominant function (dominant-to-subdominant gestures). The unresolved sevenths throughout the passage contribute to the sense of retrogression, as the dissonances are denied an authentic resolution.

In response to this passage, Grieg concludes the setting with a sequence of chromatically descending dominant-seventh sonorities, whose voice-leading model exhibits a classic Gr -V7 pattern. Thus each pattern seems to resolve a traditional chromatic subdominant function into dominant. The principal agency of function resides in the bass line, with a series of relative

-V7 pattern. Thus each pattern seems to resolve a traditional chromatic subdominant function into dominant. The principal agency of function resides in the bass line, with a series of relative  -

- patterns that discharge the subdominant agent into the dominant base. The minor seventh above each bass-pitch behaves as an augmented sixth might, with the resolution of the seventh acting in the same way as the motion from

patterns that discharge the subdominant agent into the dominant base. The minor seventh above each bass-pitch behaves as an augmented sixth might, with the resolution of the seventh acting in the same way as the motion from  -

- in a typical resolution of an augmented sixth chord. The remaining pitch behaves as

in a typical resolution of an augmented sixth chord. The remaining pitch behaves as  should in a Gr

should in a Gr -V7 resolution, descending by half-step. This sequence supports a melody that keeps returning to

-V7 resolution, descending by half-step. This sequence supports a melody that keeps returning to  , embellished by lower-neighbor leading-tones.

, embellished by lower-neighbor leading-tones.

The pattern breaks when the bass reaches  (

( ). To avoid doubling the leading tone, the tenor voice skips down to an accented

). To avoid doubling the leading tone, the tenor voice skips down to an accented  (

( of G), which is the only notated stress accent in the piece.

of G), which is the only notated stress accent in the piece.  completes the Gr

completes the Gr sonority, and resolves to a major-mode root position triad on G, embellished with a

sonority, and resolves to a major-mode root position triad on G, embellished with a  suspension figure. Thus, the chord atop

suspension figure. Thus, the chord atop  is a dominant augmented sixth, resolving to a tonic chord that receives a plagal (subdominant-to-tonic) embellishment. A notable feature of the dominant augmented sixth is the plural function implied:

is a dominant augmented sixth, resolving to a tonic chord that receives a plagal (subdominant-to-tonic) embellishment. A notable feature of the dominant augmented sixth is the plural function implied:  -

- in the bass discharges chromatic subdominant-to-tonic function, and yet supports the dominant-to-tonic discharge of

in the bass discharges chromatic subdominant-to-tonic function, and yet supports the dominant-to-tonic discharge of  -

- in the upper voice. This break in the sequential pattern signals a change in the function that is discharged from the previous chord, built on

in the upper voice. This break in the sequential pattern signals a change in the function that is discharged from the previous chord, built on  . This harmony is a straightforward secondary dominant (V7/V) that progresses to the dominant augmented sixth on

. This harmony is a straightforward secondary dominant (V7/V) that progresses to the dominant augmented sixth on  . Example 6 summarizes the preceding discussion in a single graph.

. Example 6 summarizes the preceding discussion in a single graph.

Example 6.

It is noteworthy that the final chord of the piece is a major tonic triad. While one could simply call this a Piccardy cadence, in this case, the gesture is more significant than such a straightforward interpretation might suggest. The functional analysis suggests that G major has an aspect of dominant-of-the-subdominant rather than simply tonic. Furthermore, the movement is marked attacca, proceeding directly into the fifth number in the collection, "It Was In My Youth" op. 66/5, set in C minor. Thus, the functional analysis draws attention to a reading that suggests the second half of "The Song of Siri Dale" is not really about regaining tonic at all. Rather, the G major at the end of the miniature is directed forward, toward the key of C, the tonality of the next song of the set.

Reconciling the Strategies

The detailed analysis of harmonic function casts a different light on the Schenkerian diagram of the second section of the work. The Schenkerian analysis is premised on the assumption that music should proceed according to authentic procedures of voice leading in a system that privileges I and V Stufen. The folk melody exhibits one of the paradigmatic background structures (a  -line). That a folk melody should display a classic Urlinie model is not surprising. However, the harmony does not support this reading in a unified Ursatz. A serious allowance must be made that challenges the nature of Schenker's theory of tonality and the relevance of the "Chord of Nature" as the only real progenitor of music.

-line). That a folk melody should display a classic Urlinie model is not surprising. However, the harmony does not support this reading in a unified Ursatz. A serious allowance must be made that challenges the nature of Schenker's theory of tonality and the relevance of the "Chord of Nature" as the only real progenitor of music.

The functional analysis might suggest an alternate background reading. Rather than focusing on how a harmony is prolonged in time, the functional reading considers how a harmonic function persists in time. Here I do not read stretches of music as exhibiting a deep "extension of being" despite intervening voice-leading events (prolongation). Rather, I focus on the deep "extension of doing" despite intervening voice-leading events (persistence). In either case, surface voice-leading events serve the same role, but by freeing the object that is extended from a phenomenon (a harmony), to an action (function) we have a different kind of freedom to make long-range voice-leading connections in a highly chromatic context. The long-range connections need not connect representations of the same thing (harmony), but instead, connect moments that do the same kind of thing (function).

The principal linear-functional counterpoint of the second half brings  supported by a dominant-of-subdominant harmony. As this piece does not stand alone, but instead continues without a break to op. 66/5, it may not be necessary to justify a complete Ursatz if none truly exists. In this case, although

supported by a dominant-of-subdominant harmony. As this piece does not stand alone, but instead continues without a break to op. 66/5, it may not be necessary to justify a complete Ursatz if none truly exists. In this case, although  is supported by a tonic substitute with a particular functional urgency toward the subdominant, in the bigger picture,

is supported by a tonic substitute with a particular functional urgency toward the subdominant, in the bigger picture,  of G minor also functions as

of G minor also functions as  of C minor. Thus, the deepest functional drama of "The Song of Siri Dale" may not be an authentic, or even a plagal harmonic paradigm. Rather, the functional drama plays out as a functional mutation. The key of G begins the miniature as tonic, but ends as dominant, i.e., the G of the opening is not the same G at the end of the miniature.

of C minor. Thus, the deepest functional drama of "The Song of Siri Dale" may not be an authentic, or even a plagal harmonic paradigm. Rather, the functional drama plays out as a functional mutation. The key of G begins the miniature as tonic, but ends as dominant, i.e., the G of the opening is not the same G at the end of the miniature.

The melodic descent in the second half of "The Song of Siri Dale" is therefore a middle-ground event. The melody descends through  , with consonant contrapuntal support, to

, with consonant contrapuntal support, to  . At this point, the mediant scale-step is active as a minor ninth above

. At this point, the mediant scale-step is active as a minor ninth above  in the bass. Following this, there is a melodic digression, and the upper voice

in the bass. Following this, there is a melodic digression, and the upper voice  returns as a minor seventh above the bass

returns as a minor seventh above the bass  , as the latter is on its upward chromatic path. The dominant seventh chord on C in m. 17 is not yet the goal; its metric placement on the third eighth-note of the first beat and its context denies it the status of a goal harmony. The

, as the latter is on its upward chromatic path. The dominant seventh chord on C in m. 17 is not yet the goal; its metric placement on the third eighth-note of the first beat and its context denies it the status of a goal harmony. The  however, is still strongly charged with a downward tendency, and remains an unsupported passing tone over an arpeggiation from

however, is still strongly charged with a downward tendency, and remains an unsupported passing tone over an arpeggiation from  to c in the bass. Eventually,

to c in the bass. Eventually,  discharges onto

discharges onto  in the melody, but this

in the melody, but this  supports the end of the dominant-of-the-subdominant prolongation, anchoring the endpoint of the functional persistence with a dominant augmented sixth that points strongly to

supports the end of the dominant-of-the-subdominant prolongation, anchoring the endpoint of the functional persistence with a dominant augmented sixth that points strongly to  . The dissonance is intensified as the Gr

. The dissonance is intensified as the Gr becomes a Fr

becomes a Fr sonority when a' (

sonority when a' ( ) moves to g' (

) moves to g' ( ) in the melody. Finally, the long anticipated subdominant arrives on the second beat of m. 18; g' is revealed as an anticipation of the upper-voice that accompanies this arrival. Therefore, in this middle-ground span:

) in the melody. Finally, the long anticipated subdominant arrives on the second beat of m. 18; g' is revealed as an anticipation of the upper-voice that accompanies this arrival. Therefore, in this middle-ground span:  initiates the descent;

initiates the descent;  is given consonant support;

is given consonant support;  is an unsupported passing tone accompanied by a bass arpeggiation;

is an unsupported passing tone accompanied by a bass arpeggiation;  releases the melodic tension from

releases the melodic tension from  and concludes the dominant-of-the-subdominant prolongation initiated at m. 15;

and concludes the dominant-of-the-subdominant prolongation initiated at m. 15;  resolves the functional tension with the arrival of the subdominant. In terms of the self-standing miniature,

resolves the functional tension with the arrival of the subdominant. In terms of the self-standing miniature,  is prolonged, as the form resolves to tonic through an accumulation of subdominant function. In terms of the opus as a set, the "tonic closure" is not tonic at all, but rather is the dominant of the next miniature. Thus, in this analysis I use traditional symbols associated with an "extension in time," not of a thing, but of the overriding sense of what the things encompassed do—their behavior, or function.

is prolonged, as the form resolves to tonic through an accumulation of subdominant function. In terms of the opus as a set, the "tonic closure" is not tonic at all, but rather is the dominant of the next miniature. Thus, in this analysis I use traditional symbols associated with an "extension in time," not of a thing, but of the overriding sense of what the things encompassed do—their behavior, or function.

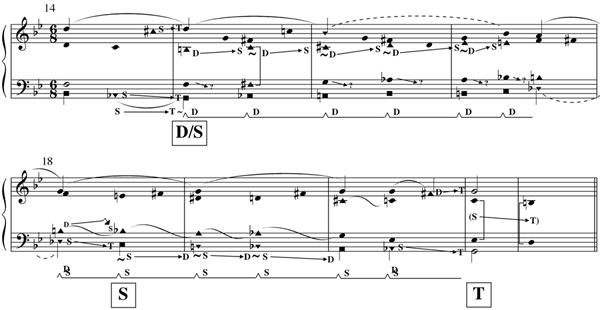

Therefore, while  may appear to be the support harmony for

may appear to be the support harmony for  in a Schenkerian reading, it is not where the principal dramatic action lies. Rather,

in a Schenkerian reading, it is not where the principal dramatic action lies. Rather,  is part of the dramatic tension that seeks C minor as the goal of the linear-functional expansion. The principal mode of tonal closure is accomplished in the plagal domain, which helps to destabilize G minor and prepare for the next miniature. An alternative reading is given in Example 7. This analysis grafts together the salient features of each analytic technique discussed in such a way as to allow the three theories to work together and produce a more comprehensive view. In this reading,

is part of the dramatic tension that seeks C minor as the goal of the linear-functional expansion. The principal mode of tonal closure is accomplished in the plagal domain, which helps to destabilize G minor and prepare for the next miniature. An alternative reading is given in Example 7. This analysis grafts together the salient features of each analytic technique discussed in such a way as to allow the three theories to work together and produce a more comprehensive view. In this reading,  is left unresolved in the miniature. Instead, it shall retrospectively be reinterpreted as

is left unresolved in the miniature. Instead, it shall retrospectively be reinterpreted as  of C, in preparation for the miniature performed attacca.

of C, in preparation for the miniature performed attacca.

Example 7.

This reading recognizes a few other notable motivic aspects of the piece. In the final 5-span middle-ground descent, this reading recognizes an inner-voice F/ voice-exchange that strengthens the dominant-of-the-subdominant persistence. Note also that the primary contrapuntal support for the descent is found in the bass line where

voice-exchange that strengthens the dominant-of-the-subdominant persistence. Note also that the primary contrapuntal support for the descent is found in the bass line where  supports

supports  , and

, and  passes as

passes as  arpeggiates to C, en route to

arpeggiates to C, en route to  . This bass line support is a chromatic version of motive x, the gapped ascent from the opening (

. This bass line support is a chromatic version of motive x, the gapped ascent from the opening ( -

- -

- ).

).

Motive x forms the structural bass of two other sections of the work. The middle-ground bass line of the final section is grounded in a plagal outline whose final tonic has been articulated with  . Thus,

. Thus,  -

- -

- -

- supports a model (tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic) functional paradigm. (This functionality operates at a level closer to the surface and the function symbols are not included here. Consult the detailed view in example 6.) Notice that this is a chromatic version of the bass line structure of the middle-section in

supports a model (tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic) functional paradigm. (This functionality operates at a level closer to the surface and the function symbols are not included here. Consult the detailed view in example 6.) Notice that this is a chromatic version of the bass line structure of the middle-section in  :

:  -

- -

- -

- supporting the same tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic functional paradigm. Both of these bass line structures have their origin in the retrograde of motive x, the gapped ascending pattern now in retrograde (

supporting the same tonic-subdominant-dominant-tonic functional paradigm. Both of these bass line structures have their origin in the retrograde of motive x, the gapped ascending pattern now in retrograde ( -

- -

- ).

).

The last voice-leading difference between the two graphs offered is in the A section of the piece. Rather than privileging the authentic harmony in the consequent phrase, this analysis privileges the Caplinian reading of the form.16 Thus, the plagal gesture i-iv6-i6 is shown to support the descent from  -

- -

- . This subtle alteration attempts to separate and elevate the status of the i chord as the initiation of a formal unit, as demonstrated in example 1.

. This subtle alteration attempts to separate and elevate the status of the i chord as the initiation of a formal unit, as demonstrated in example 1.

Conclusions

In this essay, I have tried to show that models of traditional form, linear-harmonic voice-leading models, and linear-functional models need not stand independently of one another. Rather, by critically engaging each model, the three approaches can be used to inform the creation of a single analysis that unifies their salient features in a productive way. By concentrating on the details of a voice-leading graph that is visually and structurally sensitive to traditional segmentations of musical form, a coherent long-range linear view is exposed. The function symbols that are used in place of Stufen change the tenor of the analysis, graphing functional persistence rather than harmonic prolongation. This alteration opens up highly chromatic literature to a reformulation that can accommodate harmonies that venture too far from home to have structural relevance in a mono-tonal context. Finally, other comments borrowed from Harrison's approach to harmonic function in chromatic music provide greater insight into passages that are otherwise left unexamined.

References

Brown, Matthew, Douglas Dempster and Dave Headlam. "The  (

( ) Hypothesis: Testing the Limits of Schenker's Theory of Tonality," Music Theory Spectrum 19/2 (1997): 155-83.

) Hypothesis: Testing the Limits of Schenker's Theory of Tonality," Music Theory Spectrum 19/2 (1997): 155-83.

Caplin, William E. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Cohn, Richard. "Harmony—1950 to the Present," Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 1 March 2004), http://80-www.grovemusic.com.libproxy.wlu.ca.

Gaukstad, Øystein, ed. Edvard Grieg: Artikler og Taler. Oslo: 1957, 51-52. Quoted in John Horton, Grieg, 201. London, Melbourne and Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1974.

Gauldin, Robert. Harmonic Practice in Tonal Music. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997.

Harrison, Daniel. "Nonconformist Notions on Nineteenth-Century Enharmonicism," Music Analysis 21/2 (2002): 115-60.

________. Harmonic Function in Chromatic Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Horton, John. Grieg. London, Melbourne and Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd., 1974.

Jackson, Timothy. "Schubert as 'John the Baptist to Wagner-Jesus': Large-scale Enharmonicism in Bruckner and his Models," Bruckner Jahrbuch 1991-93. Linz: Austrian Academy of Sciences, 1996. 61-108.

Kostka, Stefan and Dorothy Payne. Tonal Harmony. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 1995.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. "Towards a Reconciliation of Schenkerian Concepts with Traditional and Recent Theories of Form," Music Analysis 10/3 (1991): 233-87.

Smith, Charles J. "Musical Form and Fundamental Structure: An Investigation of Schenker's Formenlehre," Music Analysis 15/2-3 (1996): 191-297.

Swinden, Kevin J. "When Functions Collide: Aspects of Plural Function in Chromatic Music," Music Theory Spectrum 27/2 (2005): 251-85.

1The folk song is in a traditional Norwegian poetic form called the nystev, with a regular metric scheme of 4+3+4+3 for each stanza.

2Schmalfeldt (1991) studies the interaction between Caplin's reading of form and Schenkerian theory with compelling results. Her paper, which considers mostly 18th century contexts, examines how each reading contributes to a deeper understanding of the works studied when placed into dialogue with each other. I take her findings a step further with the position that if the approaches are to be truly reconciled, an analyst should be prepared to allow differences to inform and possibly to change a reading considered solely from one perspective, so long as such revisions can be accomplished in a manner that preserves the fundamental premises of the theories. If such compromises cannot be made, it is perhaps appropriate to re-examine the premises that restrict us from developing a unified view of the work.

3Gaukstad, Grieg, 51-52.

4Caplin, Classical Form.

5Following Schenkerian conventions, an Arabic numeral with a caret is used to refer to a scale-step of the governing key.

6Schenker would call an incomplete ECP an "auxiliary progression." However, in Caplin's terms, the expression ECP includes the understanding that the progression occupies at least a four-bar phrase, supporting the expression of a complete formal function.

7The most thorough Schenkerian discussion regarding  /

/ is found in Brown, Dempster and Headlam, "The

is found in Brown, Dempster and Headlam, "The  (

( ) Hypothesis." The authors argue that, in tonal music, Schenker's theory insists that

) Hypothesis." The authors argue that, in tonal music, Schenker's theory insists that  (

( ) cannot function in direct relation to tonic. Thus,

) cannot function in direct relation to tonic. Thus,  and

and  are both artificial symbols: their meaning must be mediated through another key, such as

are both artificial symbols: their meaning must be mediated through another key, such as  /IV (as one possible reading for

/IV (as one possible reading for  ) or VII/V (as a possible reading for

) or VII/V (as a possible reading for  ). Jackson, in "Large-scale Enharmonicism," is not as adamant on this point. See Jackson's figures 10a (p. 94), 11a (p. 95) and 20 (p. 104) in particular. Jackson's thesis centers on the semantic and religious significance of particular enharmonic relationships in overtly religious music (and by extension, in some non-religious music that may nevertheless have religious subtexts); his graphs suggest that there is a structural difference between

). Jackson, in "Large-scale Enharmonicism," is not as adamant on this point. See Jackson's figures 10a (p. 94), 11a (p. 95) and 20 (p. 104) in particular. Jackson's thesis centers on the semantic and religious significance of particular enharmonic relationships in overtly religious music (and by extension, in some non-religious music that may nevertheless have religious subtexts); his graphs suggest that there is a structural difference between  and

and  . Jackson uses the symbols to represent altered Stufen that retain the essential character of their unaltered form (that is,

. Jackson uses the symbols to represent altered Stufen that retain the essential character of their unaltered form (that is,  is a kind of IV and

is a kind of IV and  is a kind of V.)

is a kind of V.)

8For example Gauldin, Harmonic Practice, 573-74, suggests "in passages of intense chromaticism, we should generally reserve functional Roman numerals for the more conspicuous essential harmonies and assume a more linear approach to the chromatic harmonies, which usually arise out of embellishing passing or neighboring motion, even in passages that exhibit extended chromaticism." Kostka and Payne, Tonal Harmony, 439-40, suggest that when "They [a colorful series of unexpected chords] do not seem to imply any tonicization or to function in a traditional sense in any key . . . we simply indicate the root and sonority type of each chord." Kostka and Payne go so far as to suggest earlier on the same page that two chords under investigation are "meaningless in the context in which they occur." A similar escape clause can be found in most harmony texts, suggesting the outright equation of Roman numerals with harmonic function or "meaning."

9Often Roman numerals are faithful to the composer's spelling, but there are instances where enharmonic relationships are normalized in the symbol.

10Harrison, Harmonic Function.

11See Swinden, "When Functions Collide."

12Cohn, "Harmony."

13While  is normally emblematic of dominant-of-the-dominant function, the resolution directly to tonic undermines this potential. Instead, I read the behavior of

is normally emblematic of dominant-of-the-dominant function, the resolution directly to tonic undermines this potential. Instead, I read the behavior of  in this progression to be more closely aligned to the larger family of chromatic plagal progressions, which includes the common-tone diminished seventh and common-tone augmented sixth chords resolving to tonic.

in this progression to be more closely aligned to the larger family of chromatic plagal progressions, which includes the common-tone diminished seventh and common-tone augmented sixth chords resolving to tonic.

14Norwegian folk music often uses an intonation system that has a flat seventh degree and a sharp fourth degree. Although these intervals might not constitute a complete half-step (which would achieve an authentic  and

and  ), an interesting study might consider the relationship between this tuning system and the use of modal dominants in progressions like this one (vØ

), an interesting study might consider the relationship between this tuning system and the use of modal dominants in progressions like this one (vØ -I

-I ). This moment would be particularly enticing for this study, as it also includes

). This moment would be particularly enticing for this study, as it also includes  as a lower neighbor to

as a lower neighbor to  of G. Regardless of its possible origin in the folk style (perhaps a reference to the "hidden harmonies" to which Grieg referred [cited above, see note 3]) this analysis is concerned with the musical product as adopted into the Western tradition, and is primarily concerned with the result and harmonic function in this context. Nevertheless, as my argument shall state, this moment articulates both the return to tonic (in the context of the self-standing miniature) as well as the harmonic set-up that redefines G as the dominant of C.

of G. Regardless of its possible origin in the folk style (perhaps a reference to the "hidden harmonies" to which Grieg referred [cited above, see note 3]) this analysis is concerned with the musical product as adopted into the Western tradition, and is primarily concerned with the result and harmonic function in this context. Nevertheless, as my argument shall state, this moment articulates both the return to tonic (in the context of the self-standing miniature) as well as the harmonic set-up that redefines G as the dominant of C.

15This notation is used in Harrison, "Enharmonicism," 115-60.

16Using traditional models of form to guide Schenkerian analysis is strongly advocated by Smith, "Musical Form and Fundamental Structure." Smith is principally concerned with developing a structural theory of form so that traditional classifications of form might be invoked in the consideration and selection of an appropriate primary tone for the fundamental line. The analysis here is sensitive to Smith's position (the entire piece is interpreted as a structural upbeat into op. 66/5, and hence its background is simply  of C minor) and also seeks to explicitly align middle-ground activity to thematic design, using Caplin's theory of form as its basis.

of C minor) and also seeks to explicitly align middle-ground activity to thematic design, using Caplin's theory of form as its basis.