Education in music is most sovereign, because more than anything else rhythm and harmony find their way to the inmost soul and take strongest hold upon it, bringing with them and imparting grace, if one is rightly trained, and otherwise the contrary.—Plato1

The history of education and training in music has a breadth and depth unequalled by many disciplines. The practice of teaching music in higher education, however, is less well understood. The critical examination of personal instructional techniques and pedagogical philosophies for most music teachers tends to be informal and instinctive, or so broadly institutional as to be of limited value (the ubiquitous teaching evaluation, for example). In 2003, Susan Wharton Conkling claimed in the pages of this journal that:

For most of us employed in schools, colleges, and departments of music in higher education in the United States, teaching is a matter of intuition. Often we are good teachers; we can be engaging in the studio or classroom, and we can point to our high scores on the end-of-semester evaluations as proof of our excellence. Yet few of us can explain the basis of our teaching practices, nor can we systematically assess their impact on students. While it can be argued that all of us are, to some degree, theorists of teaching, few of us have opened up our teaching theory and practice to the review and critique of our community of professional peers in a manner that might be called scholarly.2

I would like to hope that Conkling's claim is overstated—within the field of music, after all, are numerous journals that address instructional technique and pedagogical philosophy in higher education (including the College Music Symposium)—but I do agree that our conversations about what works in teaching music can be better organized, and would certainly benefit from being subjected to the scholarly "review and critique of our community of professional peers."

This article will describe a new theory of significant learning developed by L. Dee Fink, and examine how teachers of music might incorporate his theories into their teaching. To that end, I will:

- Explain briefly the foundation of Fink's theories and his taxonomy of significant learning;

- Examine how I have incorporated Fink's taxonomy into a specific course: MUSC 303, Forms and Analysis;

- Explore the strengths and weakness of my application of this new taxonomy; and

- Critique the strengths and weaknesses of Fink's theories when applied generally to the field of music.

It is my hope that this article will contribute to and encourage the growing scholarly discussion about teaching music in higher education.

In 2003, L. Dee Fink published Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. This book examines the essential role that course design plays in creating extraordinary learning opportunities. While the phrase "significant learning" has become a catchword in much of today's pedagogical literature, its meaning is often ill-defined. Fink's multi-layered examination of what constitutes significant learning provides a crucial foundation for the rest of his book. Fink recognizes the usefulness of Bloom's (1956) traditional (cognitive) content-centered learning taxonomy. Bloom's taxonomy provides a hierarchical ordering of six types of learning (see figure 1), all based on a student's ability to manipulate and restate learned content.

Figure 1: Bloom's hierarchical sequence of educational objectives.3

Evaluation Highest level of learning Synthesis Analysis Application Comprehension Knowledge Lowest level of learning

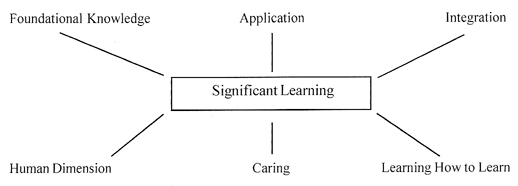

Fink, on the other hand, proposes a new taxonomy that emphasizes multiple dimensions of learning. These dimensions go beyond the content-centered focus of Bloom's theory, and address the need to give expression to types of learning such as the development of character, leadership, the ability to teach oneself, and more. Fink defines significant learning as that which causes change in the learner.4Content (which Fink calls "foundational knowledge") becomes just one of six major categories of significant learning which also include application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn. These categories can be briefly described as follows:

Foundational Knowledge: Understanding and remembering specific information and ideas. This type of learning provides a basic understanding of a particular subject.

Application: Learning how to engage in some new type of intellectual, physical, or social action. This type of learning allows the other types of learning to be useful.

Integration: Connecting learned material with other ideas, people, or realms of life. This type of learning allows students to draw parallels and connections between ideas or actions that may have seemed disparate at first, strengthening the web of meaning through inter-relatedness.

Human Dimension: Learning something important about oneself or others. This type of learning allows students to discover personal and social implications for what they are studying.

Caring: Developing new feelings, interests, and values. This type of learning allows students to interact with the subject on a personal level, creating new energy and enthusiasm for learning.

Learning How to Learn: Becoming a better student; learning how to be inquisitive and self directed. This type of learning is important because it allows students to become lifelong learners, and to engage in future studies with greater effectiveness and efficiency.5

These types of learning are interactive, rather than hierarchical, and create a synergy whereby each type of learning enhances the others (figure 2).

Figure 2: Fink's taxonomy of significant learning.6

The interactiveness of this model increases the potential for student learning. If, for example, a student learns to really care about a particular piece of music, then he or she will be interested in learning how to learn more about the piece, which in turn could increase the integration between performance and theory and history, and could help the student to develop an increasing desire to share this music with others. Intellectual development of this sort in a single student would be marvelous—but consider the implication of having an entire class or studio developing in the same way! Michael Rogers writes that one of the challenges of teaching (music theory, in this case) is that "students often lack a basic 'musical horse sense,' . . . through what I call a deficiency of constructive aural brainwashing—not enough soaking in the sonorous nature of the art."7 Fink's taxonomy provides a vehicle by which we can design our classes to give our students significant learning experiences—a soaking in the sonorous nature of our art.

Fink challenges professors to create a deep vision for the courses they teach. We as educators often have a vision for what our courses could be, but often (at least speaking for myself) lack a model for instituting change. Consider, for example, the following statements by Barbara English Maris and Clifford Madsen in a recent volume of the Symposium:

An appropriate challenge for every college or university or conservatory teacher is to create environments in which students can grow as musicians, experience their teachers' excitement about some aspect of music, and discover gratifying ways to function as musical beings.8

and

We need to develop a core of experiences that represents the best of that which we are capable. The learning from this core should be aimed at establishing in each student the ability to develop his/her basic musicianship as well as to develop a true global music understanding. This core should include a defined knowledge base as well as the ability to analyze, criticize, and choose alternatives based on a compelling personal musical value system.9

Fink's taxonomy addresses and builds on these concerns, providing a practical way of putting hopeful theory into the reality of practice. One of the great strengths of Fink's paradigm is that it provides a model for focusing the broad scope of our personal vision about education into the narrow specifics of course design. I might, for example, begin with the following vision:

To passionately build extraordinary lives in and through music.

This vision is based on careful consideration of my own abilities and talents, and also on the strengths and limitations of my institution and the type of student we typically attract. But what does this vision look and feel like when translated into specific course content? The proof is in the eating of the pudding, after all!

During the summer of 2003 I was awarded a faculty teaching fellowship that allowed me to attend a number of seminars on teaching, and culminated in a week-long workshop on course design. During this workshop I chose to redesign the culminating course in our music theory sequence, MUSC 303, Forms and Analysis. My goal was to find ways to specifically design Fink's categories of significant learning into my course. I began with a careful examination of what I wanted my students to get out of the class. What would I want them to remember five years down the road? What changes (remembering Fink's definition of significant learning) could I affect in my students' lives through this class? In the best of all worlds, what would my students get out of the class? I then tried to re-frame these goals in light of Fink's categories of learning. This self-reflection resulted in a set of course-specific learning goals, with a corresponding set of strategies to create opportunities for significant learning with each of these goals. This process influenced choices I made about readings, homework, and classroom management, and became the foundation for a radical redesign of my class, centered around Fink's six categories of significant learning.

This article will now examine the details of how I incorporated Fink's taxonomy of significant learning into my class, organized by the specific goals and strategies I used to encourage each type of learning. Many (perhaps all) of the assignments and projects that I designed for the course, however, support more than one of the categories of significant learning, so while I describe the "Pretty Polly" project below under the discussion on Caring, it should be understood that this particular activity also supports learning under Human Dimension, Application, Integration, and to a lesser extent, each of the other areas of significant learning in Fink's taxonomy.

Foundational Knowledge (Understanding and remembering specific information and ideas). Learning Goal: Students will be able to model the main musical forms, and will have a working knowledge of the specialized terms used in describing musical form. Students will also be introduced to concepts and terminology of advanced analytical techniques, such as those used in Schenkerian, feminist, and semiotic analysis. Strategy: Incorporate traditional textbook reading assignments and homework exercises, assign selected readings from sources other than the textbook, and give quizzes, a midterm, and a final examination that assesses a student's basic knowledge of models and terms. "Reading checks"—short, unannounced quizzes usually graded on the spot in classwere designed to determine how well students understood the reading, and students were also given a one-page "Forms" outline that provided an archetype for each form discussed in class (figure 3).

Figure 3: Sample of Forms Outline.

Forms Outline: Single-Movement Sonata Form

Exposition Development Recapitulation Thematic Organization Theme 1, 2, (3) any of the themes Theme 1, 2, (3) Tonal Organization Tonic for 1, Related 2, 3 Any All tonic

The single-movement sonata form (also called the first-movement sonata or sonata-allegro form) describes the typical form in the first movement of a sonata. Speaking broadly, this form consists of three events: 1) the Exposition—contrasting thematic complexes in two tonal regions (commonly tonic and dominant), followed by (2) the Development—an increasingly fluctuant thematic development of such scope and significance that it is a major division in the form, followed by (3) the Recapitulation—a restatement of themes in the tonic.10 The form is generally fast (hence the "sonata-allegro" appellation above). Speaking more narrowly, each section can be characterized as follows:

(Intro)—If this occurs, it often contrasts with the first theme in some way (tempo, character, etc.).

Exposition—where thematic ideas are presented. There will be at least 2, and sometimes as many as 4 (or more!), themes in the exposition. The themes are rarely longer than simple binary/ternary, and may exhibit a periodic structure. In chronological order, the exposition occurs like this:

- Principal theme—tonic key

- transition which modulates to a related key

- Subordinate theme—related key—usually quite different from the principal theme

- (transition, may or may not modulate)

- Closing theme or codetta—to be a theme, it must be completely set off from the subordinate theme.

The exposition ends in related key, and is traditionally repeated.

Development—free manipulation of the ideas (motives) presented earlier. It is characterized by tonal instability, in fact, almost any key relationship is likely to occur except the tonic. As the development nears its end, the dominant is usually tonicized and prolonged.

Recapitulation—the formal return, or restatement, of the themes presented in the exposition. It may be a literal restatement, or it may be a changed version, merely a token of the former themes—but there is a definite sense of return. The primary difference between the exposition and the recapitulation is that in the recap all themes are stated in the tonic key:

- Principal theme—tonic key

- retransition which does not modulate

- Subordinate theme—tonic key

- (retransition, which again will not modulate)

- (Closing theme)

(Coda)—this can become quite large, and even developmental.

Application (Learning how to engage in some new type of intellectual, physical, or social action). Learning Goal: Students will be able to make informed, logical decisions about the formal structure of pieces they are conducting or performing. Students will be able to analyze music in a variety of ways to solve practical problems (score errors, etc.), and to create a deeper understanding of the intricacies of the music they are working with. Students will also be able to use their understanding of form to improve their composition skills. Strategy: Homework exercises provide regular and highly structured chances to interact with the new techniques/models being learned. The final project (a 10-15 page analytical paper) emphasizes the application of skills learned in the class. The students choose the piece to write about, although I strongly encourage them to select a piece they are currently performing or studying so that they discover that knowledge of form can indeed make for a more informed performance. They are asked to write a rough draft (graded pass/fail), and they are provided a detailed grading rubric for the final project that emphasizes analysis over description (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Grading Rubric for the Final Project.

| Below Standard | Standard | Above Standard | |

| Mechanics | Spelling errors, inappropriate length, numerous grammatical errors, unlabeled examples and diagrams. 0-12 points. | No spelling errors, appropriate length, few grammatical errors. Musical examples and diagrams labeled correctly, and used appropriately. 13-16 points. | No spelling errors, very few grammatical errors, effective and creative use of language, clearly labeled musical examples and diagrams. 17-20 points. |

| Clarity and Organization | Weak thesis or lapses in organization that affect unity or cohesion. 0-12 points. | Organization clean and efficient, few lapses in unity or cohesion. Thesis is clearly stated and the paper follows a logical progression of ideas. 13-16 points. | Clear, engaging thesis. Essay organized from beginning to end, logical progression of ideas, fluent and coherent. 17-20 points. |

| Effectiveness of Analysis | Analysis is present, but thin, confusing, or insufficiently developed. Analysis which is not appropriate to the claims and arguments of the paper. 0-12 points. | Substantial analysis (rather than just description) that clearly documents the student's thesis. Specific details are clearly presented and are relevant to the student's thesis. 13-16 points. | Clear and engaging analysis that supports the thesis and is fully integrated with the student's discussion of those details. 17-20 points. |

Integration (Connecting learned material with other ideas, people, or realms of life). Learning Goals: Students will be able to understand the significance of formal structures in the pieces they are conducting or performing. Students will be also able to see how the study of musical form is linked to fields as diverse as astronomy and literary criticism. Strategy: The selection of supplementary reading materials was the primary strategy to meet these goals. John Barrow's chapter on music in his book The Artful Universe analyzes music from an astronomer's perspective—considering such questions as the evolutionary reason for the development of music and the potential for sentient non-terrestrials to understand our music, and punctuated with scientific discussions on the extraordinary sensitivity of the ear and the amazing possibilities for diversity within music. Lawrence Zbikowski's article "Musical Coherence, Motive, and Categorization" draws students into the realm of music cognition, in addition to being a fine system for motivic analysis. Students learn about the tremendously profitable interchange of analytical techniques between music theory and literary criticism through the chapter on feminist analysis in Vincent Leitch's American Literary Criticism from the 30's to the 80's, Lori Burns' "'Joanie' Get Angry: k.d. lang's Feminist Revision," and the exploration of narrative analysis in music through Richard Hoffman's "Debussy's Canope as Narrative Form." The interaction between music and cultural coding (an introduction to the field of semiotic analysis) is explored through Ronald Rodman's "And Now an Ideology from Our Sponsor: Musical Style and Semiosis in American Television Commercials" and John White's "Radio Formats and the Transformation of Musical Style: Codes and Cultural Values in the Remaking of Tunes."11

Human Dimension (Learning something important about oneself or others, discovering personal and social implications for what they are studying). Learning Goals: Students will learn to see themselves as experts in examining formal processes in music, and will develop the confidence to use the skills and techniques they have acquired in this class to improve their own musical performances and compositions. They will also develop confidence in their ability to read and understand professional literature in their field. Strategy: Students will engage in a number of activities to increase their confidence in using the subject matter, including the regular homework exercises and the final paper. The class presentation assignment is specifically designed to help students develop expertise in the subject. This assignment asks students to create a one-page outline for a form not covered in class, and to present their form to the class in a ten-minute presentation. The grading rubric for this assignment emphasizes organization and clarity (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Grading standards for the class presentation/one page handout:

| Below Standard | Meets Standard | Exceeds Standard | |

| Clarity (10 points) | Handout is not well-organized, material is presented in a haphazard or confusing manner. Important elements of the form are not readily discernible from the handout. Lacks fluency, unity, and cohesion. 0-6 points. | Handout is well-organized, showing clearly the most important formal or historical aspects of the form. The essence of the form is clearly defined within the handout. Spelling is accurate, prose is clear and precise, and moves forward with few lapses in unity and cohesion. 7-8 points. | Handout is well-organized, and shows exceptional organization and clarity in describing the essence of form. The layout of the handout is easily assimilated, and shows important elements of the form at a glance. Good use of diagrams. Spelling is perfect, prose is clear and precise, and the handout contains a logical progression of ideas. 9-10 points. |

| Brevity (5 points) | Not one page. 0 points. | One page, all necessary material presented. 4 points. | One page, contains a maximum amount of detail using a minimum amount of space. 5 points. |

| Accuracy of Information (10 points) | There are one or more mistakes. (-1 for each content mistake). 0-9 points. | The material is completely accurate. 10 points. | |

| Appropriateness of Musical Examples (Written and/or Aural) (10 points) | Music does not clearly exemplify the form. 0-6 points. | Music shows relatively well the points made on the handout. Only one musical example. 7-8 points. | Several musical examples that clearly model the form. 9-10 points. |

| Oral Presentation (15 points) | Poor organization, poor presentational skills, little organization, rambling or imprecise discussion, poor supporting examples. Presentation lasts longer than 10 minutes. 0-10 points. | Good, coherent organization, clear presentation with supporting details, strong teaching skills. No rambling. Exhibit evidence that you understand the form you are teaching. 11-13 points. | Excellent organization, exciting presentation, strong and concise progression of ideas, supported by outstanding examples. 14-15 points. |

The class presentation is constructed to help students find, organize, and present information regarding musical forms. The feedback from the instructor (and the other students) is designed to give them confidence that they can go out and research and understand other forms on their own.

Caring (Developing new feelings, interests, and values). Learning goals: Students will learn to appreciate the tremendously varied intricacies inherent in musical form, and will be more interested in learning how music can have multiple meanings. Students will also be curious about how to think about music in a variety of ways, and will take time to understand the form of pieces they are involved with. They will also be more attentive to how music is used by society to promote cultural codes. Strategy: One way to study the interaction between music and cultural coding (an introduction to the field of semiotic analysis) is through the articles by Rodman and White (cited above). Perhaps the most important assignment supporting this type of learning, however, is the "Pretty Polly" project. This project occurs after the readings from Leitch and Burns (which are incorporated within the traditional textbook discussion on song forms). Burns' article examines how k.d. lang's performance of a popular tune from the 1950's—"Johnny Get Angry"—turns into a social commentary on violence in relationships. I then take a performance of the bluegrass standard "Pretty Polly" (performed by Ralph Stanley and Patty Lovelace on PBS' All-Star Bluegrass Celebration) and ask students to write a short essay that examines the disconnect between the lyrics of the text—which describe the murder of a young woman by her lover—and the upbeat, playful performance by Stanley and Lovelace.12 Students must then take the analysis one step further by creating in groups of three or four their own performance of Pretty Polly. The student groups are given complete freedom in how to change the performance style, chords, tempo, or style of the song. They are then asked to analyze their own work and describe to the class why they changed what they did, and how their changes affect the relationship between the lyrics and the performance. The Pretty Polly project is designed to give students ownership of the music, and, hopefully, a growing sense of care for the topic, not to mention a deeper respect for the interaction (or lack thereof) between text and performance.

Learning how to learn (Becoming a better student; learning how to be inquisitive and self directed). Learning goals: Students will learn how to read and understand complex articles dealing with musical analysis. Students will learn some of the more significant resources in the area of musical analysis. Students will learn how to ask useful questions about music they do not understand. Strategy: Many students have not attempted to read "professional" literature in the field of music theory/analysis, although almost all are capable of it—they simply need some direction about how to proceed. To this end, I have devised "reading guides" for each of the non-text reading assignments. The reading guides help students to discover main ideas, work through difficult concepts, and to become acquainted with a dictionary—even as I must do as I read scholarly literature—and to gain confidence in their ability to get through academic articles. In addition to the reading guides, the end-of-term paper is designed to help students identify meaningful questions about the music they choose to write about. These questions are then developed into a thesis which is supported by the student's analysis.

Strengths and weaknesses of my application:

It is difficult to be entirely objective on a project in which you have put a great deal of time, but I think it is worthwhile to consider the strengths and weaknesses of my application of Fink's principles. I think there are a number of strengths. First, many of these activities I have described had already been incorporated into the Forms and Analysis course before I read Fink's book, but his principles helped me to think about them in deeper ways, and to organize them within an overall learning paradigm. I was able to reduce my reading list and pick new articles that emphasized elements of his taxonomy. The students are enthusiastic about many of the tasks that I now use, and I see a willingness in them to dive into difficult topics. The level of discourse in class, for example, has definitely deepened with the changes I have made. I see weakness in the fact that I have limited reference to Schenkerian theory; it surely deserves as much time as some of the other topics I do cover, but I have yet to find an article that will really make the impact I am looking for in this area. To be absolutely blunt, I am also not sure that I have reached my goals for "Human Dimension"—I do not see much evidence that students who have passed my class are confidently incorporating new analytical techniques into their performance preparation. The work for them in accomplishing this type of task is not yet worth (in their perception) the rewards. It is very difficult to inculcate a work ethic into students that lasts beyond the course.

Strengths and weaknesses of Fink's theories as applied to music:

I think that Fink's taxonomy is highly applicable to the field of musical—though I have put it in practice only in my field of music theory. I would be eager to discover how others might incorporate this paradigm into their music appreciation or music history courses, pedagogy courses, and especially applied lessons, where it might have limited usefulness. One of the prime criticisms of theories such as Fink's is always going to revolve around content. Some may see the "Pretty Polly" exercise, for example, as simply a well-constructed waste of time during which I could have spent another day examining another set of Germanic art songs from the mid-19th century. Content is important, and I do not disparage such opinions. Content, for example, is the easiest to objectively grade—much easier than Fink's other categories. And many teachers (including myself) feel overwhelmed by the number of new pedagogical movements that have developed in recent decades. Michael Rogers summarizes this problem admirably:

Considering this wealth of possibilities suggests that a major problem for future curriculum designers will circle around the issue of breadth vs. depth. We already have too many good choices to include in undergraduate theory. How can we possibly consider even more? Should we teach a restricted repertoire of concepts and literature in great detail or should we cover many things at the risk of superficiality?13

The changes I have made within my forms class have resulted in less time to cover "basics." This is mitigated in part by my ability (by virtue of being the director of the theory/composition area) to incorporate aspects of formal content throughout the theory sequence, so that the students come to Forms and Analysis with a basic familiarity with many of the forms.

Fink's Creating Significant Learning Experiences provides a highly useful model for course design around a revolutionary paradigm of significant learning. As Philip Candy states:

If learning is regarded not as the acquisition of information, but as a search for meaning and coherence in one's life and, if an emphasis is placed on what is learned and its personal significance to the learner, rather than how much is learned, researchers would gain valuable new insights into both the mechanisms of learning and the relative advantages of teacher-controlled and learner-controlled modes of learning.14

I believe that my classes have changed, for the better, through the application of Fink's theories. I firmly answer to Fink's pedagogical call to arms:

We can continue to follow traditional ways of teaching, repeating the same practices that we and others in our disciplines have used for years. Or we can dare to dream about doing something different, something special in our courses that would significantly improve the quality of student learning. This option leads to the question faced by teachers everywhere and at all levels of education: Should we make the effort to change, or not?15

I believe that it is to our benefit to consider strongly this new paradigm—to open up Fink's theories for review and critique in a scholarly manner—for they provide a stimulating model for bringing deep, meaningful learning to our music courses.

List of References

Barrow, John. The Artful Universe. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. 1995.

Berry, Wallace. Form in Music, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1986.

Bloom, Benjamin, ed. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: David McKay Company, Inc. 1956.

Burns, Lori. "'Joanie' Get Angry: k.d. lang's Feminist Revision." In Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis, 93-112. John Covach and Graeme M. Boone, eds. New York: Oxford University Press. 1997.

Candy, Philip C. Self-Direction for Lifelong Learning: A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 1991.

Conkling, Susan Wharton. "Envisioning a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning for the Music Discipline." College Music Symposium 43 (2003): 55-64.

Fink, L. Dee. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 2003.

Hoffman, Richard. "Debussy's Canope as Narrative Form." College Music Symposium 42 (2002): 103-11.

Leitch, Vincent. American Literary Criticism from the 30's to the 80's. New York: Columbia University Press. 1988.

Lickona, Terry, prod. All-Star Bluegrass Celebration (DVD format). Tampa, FL: LickonaVision, Inc., Rainmaker Productions, Inc. 2002.

Madsen, Clifford. "Music Education: A Future I Would Welcome." College Music Symposium 40 (2000): 84-90.

Maris, Barbara English. "Redefining Success: Perspectives on the Education of Performers." College Music Symposium 40 (2000): 13-17.

Merritt, A. Tillman. "Undergraduate Training in Music Theory." College Music Symposium 40 (2000): 91-100. Reprint from College Music Symposium 5 (1965): 21-35.

Plato. Republic, I, trans. Paul Shorey. Quoted in Oliver Strunk, ed. Source Readings in Music History: Antiquity and the Middle Ages. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1965.

Rodman, Ronald. "And Now an Ideology from Our Sponsor: Musical Style and Semiosis in American Television Commercials." College Music Symposium 37 (1997): 21-48.

Rogers, Michael. "How Much and How Little Has Changed? Evolution in Theory Teaching." College Music Symposium 40 (2000): 110-16.

White, John Wallace. "Radio Formats and the Transformation of Musical Style: Codes and Cultural Values in the Remaking of Tunes." College Music Symposium 37 (1997): 1-12.

Zbikowski, Lawrence. "Musical Coherence, Motive, and Categorization." Music Perception 17.1 (Fall, 1999): 5-43.

1Plato, Republic, in Strunk, ed., Source Readings, 8.

2Conkling, "Envisioning a Scholarship," 55.

3Bloom, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, see especially pp. 201-7.

4Fink, Creating Significant Learning Experiences, 29, 56.

5Ibid., 30-32.

6Ibid., 33.

7Rogers, "How Much and How Little Has Changed?," 110. The quote from within Rogers' statement comes from Merritt, "Undergraduate Training in Music Theory," 91.

8Maris, "Redefining Success," 13.

9Madsen, "Music Education," 86.

10Berry, Form in Music, 148.

11See list of references for full citations.

12Lickona, All-Star Bluegrass Celebration.

13Rogers, "How Much and How Little Has Changed?," 116.

14Candy, Self-Direction for Lifelong Learning, 415.

15Fink, 1.