Introduction: Evoking Childhood Musically

Carnival of the Animals. Children’s Corner. Mother Goose. Musical depictions of the childhood experience have attracted a wide spectrum of composers, reaching an apex in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Since such music generally makes limited technical demands and features accessible melodies, diatonic harmonies, and periodic (often ternary) formal structures, the appeal is logical. The modern history of music written for or about children begins with two piano cycles: Robert Schumann’s Kinderszenen, Op. 15 (1838) and Album für die Jugend, Op. 68 (1848). The latter work in particular reflects contemporary advances in child psychology pioneered by Jean-Jacques Rousseau and adapted by later educators both within and outside France. In Emile (1762), Rousseau argued for the inherent goodness of children while also positing the arts as crucial to the education of the whole child. Such an approach required learning materials that were age-appropriate, easily grasped, and presented in sequence.

As Lora Deahl has noted, Album für die Jugend meets Rousseau’s criteria, including his seminal concept of “learning readiness.” In her view, the work “not only revolutionized attitudes concerning music education, but also inaugurated an entirely new genre of piano literature–programmatic music written explicitly for children.”1 She views the cycle as a precursor to later works by Bartók, Kabalevsky, Prokofiev, Satie, and others. Deahl considers works written specifically for children, as well as reminiscences of childhood intended for adults, exemplified by Kinderszenen. The boundaries between the two styles, however, are not always clearly defined.

To date, scholarly discussions of music and childhood have centered on nineteenth-century Germany and Schumann in particular. Roe-Min Kok has examined ways the Album was used to “shape national identities” through icons including “the musically traditional, solidly German farmer.” This contrasts with Schumann’s representations of national styles and ethnic groups whose differences are highlighted by prominent augmented intervals and chromaticism. As one example, she cites the opening of “Marinari,” where prominent tritones define the Italian sailors as exotic others. Kok further identifies compositional tropes that evoke childhood, including melodic spans of a sixth or less, stepwise motion, and equal voicing in both hands.2 French children’s music has received comparatively less attention, confined primarily to well-known examples such as “Jimbo’s lullaby” from Debussy’s Children’s Corner. But evocations of childhood are also not limited to keyboard music. This essay considers one important and overlooked work, Francis Poulenc’s last song collection, La courte paille (The short straw). The cycle contains text and music that appeals to children but also contains substantial relevance for its composer and his adult audience.

Poulenc’s Last Decade (1953–1963)

By the early 1950s, Francis Poulenc was the most celebrated composer of mélodie in France, with well over one hundred songs to his credit. The final decade of Poulenc’s career was also a period of intense turmoil and creative inertia. While composing his largest and most important opera Dialogues des Carmélites, Poulenc suffered what Richard D.E. Burton calls “incapacitating breakdowns” resulting from a “combination of artistic self-doubts and anguish over his personal relationships.” By spring 1959, he was contemplating suicide.3 Guilt over his homosexuality and the inability to find a stable romantic relationship often sent the composer into fits of depression, relieved mostly by work and the companionship of trusted friends. Memories of his previous relationship with Raymonde Linossier, to whom he hastily proposed marriage in 1928 only to be immediately rejected, further exacerbated ambiguous feelings regarding his sexual identity. Poulenc’s conflict is exemplified most vividly in the 1958 monodrama La voix humaine (The human voice), a work with strong autobiographical undertones.4 After completing another monodrama, La dame de Monte Carlo (The woman of Monte Carlo), Poulenc focused on church music and chamber pieces. For a composer who had devoted much of his career to the composition of mélodie, the paucity of song composition after 1950 is striking, with his output confined mostly to individual songs and brief sets. It was not until 1960 that Poulenc, inspired by the poetry of Maurice Carême, would return for the last time to composing songs.

Poulenc and Childhood

Poulenc’s fascination with musical depictions of childhood began almost three decades before the composition of La courte paille with the Quatre chansons pour enfants (Four songs for children) of 1934.5 Almost entirely unknown today, the collection features texts by his associate Jean Nohain, writing under the pseudonym Jaboune.6 The set as a whole is charming and at times ribald, extending from a song about an errant child set in mock-serious G minor to the centerpiece, “Nous voulons une petite soeur” (We want a little sister). Poulenc employs a lively, music-hall idiom to depict a rowdy group of greedy daughters who refuse a litany of elaborate Christmas gifts in favor of “une petite soeur” (a little sister) and later “deux soeurs exactement pareilles” (two identical sisters). The repetitive style recalls the patter songs of Poulenc’s “Les Six” period, especially his 1919 Cocteau cycle Cocardes, although here the singer is required to play the parts of narrator, mother, and children.7 The verse-refrain form supports unexpected changes of style, mood, and harmony, reflecting an increasingly exasperated mother. She can only listen in amazement as the children refuse her generosity with a fivefold unison cry of “non.” After the family grows to a grand total of nineteen, the mother declares there will be no gifts, including additional babies, for that year. It is easy to understand why Poulenc, who adored puns and words games, would be drawn to this poetry. The tongue-in-cheek style and witty text strongly anticipates Courte paille.

Another significant precursor to Courte paille is Poulenc’s setting for piano and reciter of the opening volume in Jean de Brunhoff’s wildly successful Babar series. The composer referred to L’Histoire de Babar, le petit éléphant (The story of Babar, the little elephant), as “eighteen glances at the tail of a young elephant,” a witty jab at Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’enfant Jésus (Twenty glances at the child Jesus), a work he greatly admired. Poulenc was inspired to write Babar while visiting his young cousins in summer 1940 for whom he improvised the music during a reading of the story, much as Maurice Ravel has done for Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose). Poulenc recorded the work twice and performed it frequently on radio. Although extended discussions of Quatre chansons pour enfants and Babar are beyond the scope of this essay, both are prime examples of Poulenc’s “lifelong obsession with childhood” that also provided important models for La courte paille.8

Denise Duval and Maurice Carême

The direct impetus for La courte paille may be traced to soprano Denise Duval, who was born in 1921 and retired from singing in the 1960s. Of the many women who influenced and inspired Poulenc during his career, none was more significant. She was a colleague, artistic muse, confidant, and close friend. Duval’s own performance career was highly diverse, with roles ranging from Madama Butterfly to Mélisande and appearances at Paris’s Folies Bergères, Opéra, and Opéra-Comique.9 First selected by Poulenc to create the role of Thérèse in the 1944 Apollinaire farce Les mamelles de Tirésias (The breasts of Tirésias), she later won the coveted roles of Blanche in Dialogues and Elle in Voix humaine. There are frequent references to Duval in Poulenc’s correspondence, in which he referred to her as his “ideal muse” and “the adorable one.”10 To date, no documentation describing Duval’s opinion of Maurice Carême’s writings or Poulenc’s first exposure to his poetry has been uncovered. But a desire for simpler, more direct imagery likely played a part in the decision to set Carême’s texts. After decades of using the elusive poetry of Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Eluard, and Max Jacob, he was searching for fresh inspiration and a new outlet for Duval’s talents.11

Carême’s position as a decidedly minor poet in the midst of the literary giants of his era has led to disparaging comments regarding Courte paille. Pianist Graham Johnson writes that the collection reveals a composer who “no longer has the energy to tussle with the complexities of great poetry.”12 Although Johnson’s comments have merit, he fails to take into account Poulenc’s personal connection with the lyrical qualities and utopian themes of Carême’s writing. Described by baritone Pierre Bernac as the “poet of children” and “the poet of peace,” Carême was born in the same year as Poulenc but outlived him by more than a decade.13 His work has often been overlooked in studies of modern French literature. In a 1965 biography, Jacques Charles noted that his poems do not always fit modern tastes because of their perceived naïveté.14 Charles further highlight’s Carême’s use of textual simplicity, emotion, mystery, and the sonorous quality of his texts, creating “une langage qui chant” (a singing language).15

Much of Carême’s poetry is written in a whimsical style appropriate for children. For his cycle, Poulenc selected seven diverse poems from two collections titled La cage aux grillons (The cricket’s cage) and Le voleur d’étincelles (The thief of brightness). The author himself provided the overall title for the set, derived from the children’s game of drawing straws, and he permitted Poulenc to change the titles of several poems in their song versions. After selecting the poetry, composition proceeded rapidly, with Poulenc composing the cycle in July and August of 1960 and completing it by 11 August. His intention was to have Duval perform Courte paille almost immediately. He wrote:

On some charming poems by Maurice Carême, half-way between Francis Jammes and Max Jacob, I have composed seven short songs for Denise Duval or, more exactly, for Denise Duval to sing to her little boy of six. These sketches, by turns sad or mischievous, are unpretentious. They should be sung tenderly. That is the surest way to touch the heart of a child.16

To Poulenc’s surprise, Duval rejected the work, never performing it in its entirety. Her claim of vocal unsuitability has been questioned by Benjamin Ivry, who notes that such an excuse was “hardly believable, given Poulenc’s knowledge of her singing.”17 What, then, could explain her lack of interest? Perhaps she was responding to Poulenc’s increasingly volatile behavior towards friends and colleagues. Depending on his mood, rehearsals could be canceled, postponed, or derailed while Poulenc complained about his latest trauma. Even his close friend and recital partner Bernac required extended periods away from the composer, and it is likely that Poulenc’s erratic behavior created an atmosphere from which Duval also needed a respite.18

Duval’s only recorded performance of excerpts from Paille occurred on French television in February 1961, when she sang the second and fifth songs with the composer accompanying. The broadcast is instructive in several ways, as it is preceded by a brief interview in which Poulenc discussed the origin of the cycle and implied that a premiere was imminent. Duval may well have performed on this occasion as a personal favor. Their relationship is visibly awkward, especially if compared with an earlier television appearance in May 1959, when she sang excerpts from three Poulenc operas.19

La courte paille

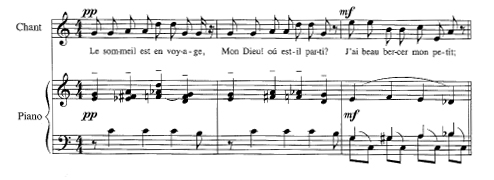

The opening song, “Le sommeil,” (Sleep), paints a scene universally familiar to parents.20 In depicting a restless child who refuses to sleep, the vocal line stays largely within the range of a fifth, supported in the piano by c' and later G pedal points and a bass ostinato pattern that imitates the act of rocking. Ostinati are not unique to “Le sommeil,” as similar patterns appear in several of Poulenc’s vocal and instrumental works, including “Bonne journée” (Good day) from Tel jour, telle nuit (Such a day, such a night) and the opening of the Clarinet sonata. But here, the rocking motive combined with a hypnotic vocal line and low dynamic level creates a soothing mood reminiscent of a lullaby (Example 1). The text assumes two alternating subject positions: anxious thoughts from the parent unable to calm the child, and direct address using childlike imagery, exemplified by lines such as “dans le ciel noir la Grande Ourse a enterré le soleil” (the great bear has hidden the sun in the black sky).

Example 1: La courte paille, “Le sommeil,” mm. 1–3.

The musical style of “Le sommeil” resonates with scholar Karen Bottge’s recent work on the Brahms Wiegenlied, composed to celebrate the birth of a child to the composer’s friends. In discussing this famous song, Bottge considers Brahms’s use of the voice and the piano to create an “aural envelope that enfolds the mother-child dyad in a ring of sensual pleasure, a pleasure which is experienced not only in the immediacy of childhood phonetic instruction, but also lingers well into adulthood.” She refers to Guy Rosolato’s concept of the mother’s voice (la voix maternelle) as a “blanket of sounds that surrounds the infant from all sides.”21 Although Bottge and Rosolato refer specifically to the bond between mothers and children, their work can be transferred to similar effects with fathers. Poulenc never specifically discouraged men from singing La courte paille, labeling it simply a set of songs “pour chant et piano.” A male voice with its lower range, richer overtones, and darker timbre is equally capable of creating such a musical enclosure. The song closes on an ambiguous G7 sonority, perhaps suggesting that the restless child has finally fallen asleep.

Poulenc’s song cycles often alternate between slow, intimate songs and faster, extroverted ones. The text of “Quelle aventure” (What an Adventure), described as “surreal” by Wilfrid Mellers, recalls the whimsy of Mamelles de Tirésias. The text may be interpreted as a parent telling the child a bedtime story or an older child making up his own.22 The fast tempo, mock-serious chromaticism, and exaggerated vocal leaps (including numerous octaves to highlight the words “Mon Dieu”) all contribute to the effect. This mélodie is also a good example of what Keith W. Daniel calls Poulenc’s “patter songs.”23 With “La Reine de Coeur” (The Queen of Hearts), we enter into a darker realm of childhood fantasy. Titled “Vitres de lune” (Moon windows) in Carême’s poem, the liquid vocal line and rich harmonies punctuated by seventh and ninth chords mask a more sinister character than a mere Queen. While Ivry’s reference to her as “an ice maiden as dangerous as Schubert’s Erlkönig” may be hyperbolic, the song and its mysterious references to “son château de givre” (her castle of frost) and places where “les jeunes mortes viennent parler d’amour” (the young dead come to speak of love) are intense and slightly menacing sentiments.24 Cast in a free ABA form, the shift from tonic E minor to the parallel major in the closing bar is a striking gesture that Mellers likens to the sudden appearance of the Queen’s shining castle.25

Lasting only about 25 seconds, “Ba, be, bi , bo, bu” is a transitional song based on the well-known fairy tale of Puss-n-boots. The frivolous text recalls children’s word games and leads to an abrupt conclusion in Eb minor. This sets the tone for a strong contrast of mood and style in “Les anges musiciens” (The angel musicians), which opens with the clearest appropriation of Mozart in the Poulenc song canon. In describing the second movement of his 1932 concerto for two pianos, Poulenc confirmed his admiration for Mozart by writing that “In the Larghetto of this concerto, I allow myself, for the first theme, to return to Mozart, for I cherish the melodic line and I prefer Mozart to all other musicians.”26

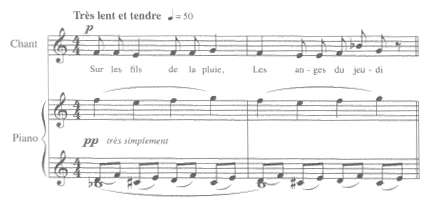

In “Les anges musiciens,” Mozart’s music becomes a heavenly soundtrack played by “les anges du Jeudi” (Thursday angels). Carême’s poetry evokes an angelic Mozart reminiscent of Maynard Solomon’s concept of the “eternal child.” As Solomon has shown, this view stands in stark contrast to Mozart’s own desire after 1780 to “leave behind childhood and its subjections, to shatter the little porcelain violinist with his frozen perfection.”27 But for Poulenc, suffering from depression and acute anxiety, Mozart’s music and his childlike image became sources of comfort, a musical balm.

The poetry of this song has been criticized more than any other in the cycle, with Ivry noting its “embarrassing lines.”28

The song opens with a near quotation of the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in D Minor, K. 466 (Examples 2 and 3). But soon the harmonies turn from Mozartian to modern before closing on a tentative E7 sonority, evoking the ringing sound of harps.29 The colorful harmonies and expressive chromaticism effectively reflects the whimsical text.

Example 2: Mozart, Piano Concerto in D Minor, K. 466, ii, mm. 1–7.

Example 3: Poulenc, La courte paille, “Les anges musiciens,” mm. 1–2.

With “Le carafon” (The little carafe), the childhood whimsy of the second and fourth songs returns, as a precocious carafe finds his quest for a companion answered by Merlin the Magician.30 The poetry includes a narrator, Merlin, and the carafe itself, each differentiated by vocal range and musical style. In depicting this broad poem, Poulenc calls for a fast tempo, unprepared harmonic shifts, numerous ostinati, and “crazily free tonality.”31 The song opens in D minor but never settles comfortably into one key, creating fleeting images similar to a fantasy bedtime story. Aside from the tempo and tongue-twisting words, the greatest performance challenge is differentiating the characters, an obstacle not unlike Schubert’s Erlkönig but in a radically different type of poem and song. The high tessitura and tense vocal style of the opening, depicting the carafe, leads to a lower vocal range and mock-serious chromaticism with the appearance of Merlin. Poulenc’s tendency to employ repetitive blocks of sound, a technique borrowed from Stravinsky, is also evident. Almost as quickly as the song began, it ends on an inconclusive F# minor sonority.

Poulenc’s indication of a “très long silence” before “Lune d’Avril” (April Moon) highlights the importance of this seventh mélodie as the summit of the collection. This is not the first time Poulenc reserved his most profound sentiments for the last song of a cycle. Nevertheless, the placement of “Lune d’Avril” after its predecessors is a striking gesture.32 The poetry contains surrealistic imagery that appeals equally to adult and children’s imaginations.

“Lune d’Avril” (excerpt)

Poulenc and especially Carême were deeply affected by war and violence. Poulenc’s own military service in World War I and anxiety during the later Nazi occupation strongly influenced his outlook, and these events may have served as impetus for closing the cycle with this specific poem.

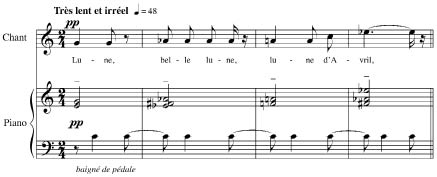

The opening phrase, with its c' pedal point under subtly shifting harmonies, recalls a parallel moment in “Le sommeil,” establishing a cyclical connection (Example 4). The vocal line is restrained and prayer-like, focused initially on g' but rising for the line “et surtout le pays où il fait joie” (and above all the land where joy lives). This leads to a fortissimo climax on g", supported by an F minor 9th chord.33 A sudden drop to ppp foregrounds the most significant line in the poem and, perhaps, the entire cycle: “on a brisé tous les fusils” (all the guns have been destroyed). Carême’s utopian call for peace encapsulates his pacifist worldview, a perspective shared at least in part by Poulenc.

Example 4: La courte paille, “Lune d’Avril,” mm. 1–4.

The song concludes with an abbreviated “A” section followed by a piano postlude that includes another c' pedal. The concluding bars, marked pppp, never fully resolve, creating a mood of nostalgia and sadness. They could conceivably be played ad infinitum. This ambiguous close, recalling Steven Huebner’s concept of key moments in French music that are “an end without an end,” could be read as a commentary on the futility of war or a glimpse of hope in the midst of despair.34 Even the final sonority fails to provide closure. Mellers views this widely-spaced C7 chord as one that “suspends the child in time, waiting for ensuing life–and for inevitable death.”35

Conclusion

Following their 1961 television performance, Poulenc asked Duval to sing the entire cycle for two 1961 concert events, but she again refused. The premiere was given by soprano Collete Herzog and Jacques Février.36 The scholarly view of La courte paille as a footnote in the oeuvre of France’s greatest modern song composer has led to neglect of his final effort in the genre he preferred above all others. Criticisms extend from Ivry’s dismissal of the set as “neurotic cradle songs” to Keith W. Daniel’s more reasoned placement of the cycle into the category of “simple, child-like songs.”37 While few would argue that Paille equals the musical or poetic inspiration of Tel jour, telle nuit or Banalités (Banalities), it reflects a crucial era in the composer’s personal and creative life. At key moments, Poulenc wrote music inspired by children, including Quatre chansons in the 1930s, Babar in the 1940s, and Courte paille in the 1960s.

There are also connections between La courte paille and Poulenc’s final completed work, the Sonata for oboe, which premiered in 1963 only months after his death. The first movement, “Elégie,” gives way to a frenetic scherzo not far removed from the second and sixth songs of Paille, followed by a “Déploration” finale whose closing bars employ an ostinato pattern similar to “Lune d’Avril.” The constant shift between gaiety and reflective melancholy–reflecting the composer’s own state of mind during a turbulent period–is clearly evident in both works. La courte paille thus emerges as more than a collection of children’s music, although it certainly appeals to younger listeners. It is a crucial link to Poulenc’s final compositions. Above all, the cycle potently demonstrates that the minor works in a composer’s output may in fact contain significant personal resonance.

Bibliography

Audel, Stéphane. Francis Poulenc: Moi et mes amis. Paris: La Palatine, 1963.

Bernac, Pierre. Francis Poulenc: The Man and His Songs. New York: Norton, 1977.

Bottge, Karen M. “Brahms’s ‘Wiegenlied’ and the Maternal Voice.” 19th-Century Music 28, no. 3 (Spring 2005): 185–213.

________. “Brahms’s Lullaby and the Maternal Voice.” Paper presented at Society for Music Theory annual meeting, Madison, WI, 2003.

Buckland, Sidney, ed. Francis Poulenc, Echo and Source: Selected Correspondence, 1915–1963. London: Victor Gollancz, 1991.

Charles, Jacques. Maurice Carême. Paris: Seghers, 1965.

Chimènes, Myriam. Francis Poulenc: Correspondence, 1910–1963. Paris: Fayard, 1994.

Clifton, Keith E. “Mots cachés: Autobiography in Cocteau’s and Poulenc’s La Voix humaine.” Canadian University Music Review 22, no. 1 (2001): 68–85.

Crowson, Lydia. The Esthetic of Jean Cocteau. Hanover, NH: The University Press of New Hampshire, 1978.

Daniel, Keith W. Francis Poulenc: His Artistic Development and Musical Style. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982.

Deahl, Lora. “Robert Schumann’s Album for the Young and the Coming of Age of Nineteenth-Century Piano Pedagogy.” College Music Symposium 41 (2001): 25–42.

Huebner, Steven. “Ravel’s Child: Magic and Moral Development.” In Musical Childhoods and the Cultures of Youth, edited by Susan Boynton and Roe-Min Kok, 69–-88. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2006.

Ivry, Benjamin. Francis Poulenc. London: Phaidon, 1996.

Johnson, Graham. A French Song Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Kok, Roe-Min. “Of Kindergarten, Cultural Nationalism, and Schumann’s Album for the Young.” The World of Music 48, no. 1 (2006): 111–63.

Mellers, Wilfrid. Francis Poulenc. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Poulenc, Francis. Journal de mes mélodies. Translated by Winifred Radford. London: Victor Gollancz, 1985.

________. La courte paille. Paris: Max Eschig, 1960.

________. Quatre chansons pour enfants. Paris: Enoch, 1935.

Roy, Jean. Francis Poulenc. Paris: Seghers, 1964.

Schmidt, Carl B. Entrancing Muse: A Documented Biography of Francis Poulenc. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2001.

________. The Music of Francis Poulenc (1899–1963): A Catalogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Solomon, Maynard. “Mozart and the Myth of the Eternal Child.” 19th-Century Music 25 (1995): 95–106.

Tubeuf, André and Elizabeth Forbes. “Denise Duval.” The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan, 1992.

Weide, Marion Sue. “Imagery and Style in the Art Song of Poulenc.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1975.

Endnotes

1Deahl, “Robert Schumann’s Album,” 25-37. Deahl notes that Schumann’s Album inspired several later collections, including Schumann’s Lieder-Album für die Jugend, Op. 79 and Drei Klaviersonaten für die Jugend, Op. 118. Examples of French music representing childhood but intended primarily for adults would include Bizet’s Jeux d’enfants and Fauré’s Dolly suite.

2Kok, “Of Kindergarten,” 113–28.

3Burton as cited in Ivry, Francis Poulenc, 202.

4For a detailed examination of this work and its autobiographical implications, see my “Mots cachés.” For more on Poulenc’s complex relationship with Linossier, see Ivry, Francis Poulenc, 63–5.

5Poulenc’s only child, Marie-Ange, was born in 1946. She later became a ballet dancer. As noted by Ivry, “fathering a child with a woman was not unheard of in Poulenc’s circle of gay friends” and such an act reflected Poulenc’s lifelong appreciation of women and children. See Ivry, Francis Poulenc, 138.

6Jean Nohain was the son of poet and writer Franc-Nohain (pseudonym of Maurice Le Grand), who provided the libretto for Ravel’s 1911 opera L’heure espagnole. For additional information on Jaboune, see Schmidt’s Entrancing Muse, 209 and 227; and Schmidt, The Music, 231–3.

7The Quatre chansons are published separately, and may be performed in any order.

8For a detailed examination of the genesis of Babar, see Mellers, Francis Poulenc, 173; Schmidt, Entrancing Muse, 311–13; and Schmidt, The Music, 360–5.

9Tubeuf and Forbes, “Denise Duval.”

10Buckland, Francis Poulenc, 303.

11For a lucid summary of Carême’s life and works, see Charles, Maurice Carême, especially pp. 5–34. Poulenc’s decision to set Carême’s work apparently came rather late, as the poet began sending Poulenc copies of his poems only after 1953. Poulenc was likely aware of his work much earlier. See Schmidt, Entrancing Muse, 442.

12Johnson, French Song Companion, 359.

13Bernac, Francis Poulenc, 163.

14A brief summary of Carême’s career followed by informative commentary on each song in Courte paille is provided in Bernac’s Francis Poulenc, 163–9. Composers besides Poulenc who have set Carême’s poems include Darius Milhaud and Henri Sauguet.

15Charles, Maurice Carême, 29.

16Translation mine. For the original French text, see Francis Poulenc, Journal, 109.

18For more on Poulenc’s relationship with Bernac, see Mellers, Francis Poulenc, 179–81.

19Both excerpts, as well as performances of the Concerto for Two Pianos in D Minor, the Concerto for Organ, and assorted vocal and keyboard works, are available on the DVD Poulenc and Friends (London: IMG Artists Classic Archive DVB 3102019, 2005).

20Meller’s refers to the song as a “general comment on the human condition.” See Francis Poulenc, 174.

21Bottge, “Brahms’s ‘Wiegenlied,’”187.

22Poulenc himself acknowledged the influence of Mamelles on Paille. See Mellers, Francis Poulenc, 174.

23Daniel, Francis Poulenc, 251. Daniel divides the songs into six broad categories, including “prayer-like songs,” “tender, lyrical songs,” and “dramatic songs.”

25Mellers, Francis Poulenc, 174.

26Daniel, Francis Poulenc, 149.

29Mellers notes that Mozart used an actual children’s song as theme for the rondo finale of his final piano concerto, K. 595 in Bb. See Francis Poulenc, 176.

32An example of a similar closing song is “Sanglots” from Banalités.

33The vocal line of “Lune d’Avril” calls to mind Lydia Crowson’s work on Cocteau. She notes that his texts often assume “the power of incantation” at intense moments. See Crowson, The Esthetic, 62.

34Huebner, “Ravel’s Child,” 88. Huebner cites especially the unresolved chord that closes Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges.

35Mellers, Francis Poulenc, 178. The closing bars with their static chords and emphasis on “lune” evoke a similar passage in “Le Grillon” from Ravel’s Histoires naturelles. I thank Jessie Fillerup for pointing this out.

36While the premiere took place at the 1961 Royaumont Festival, the specific date is unclear. See Schmidt, Entrancing Muse, 442.

37Ivry, Francis Poulenc, 212 and Daniel, Francis Poulenc, 250.