In the 1950s, a pianist named Martin Denny made a percussion-heavy recording of a tune called “Quiet Village.” This recording reached Number 4 on Billboard’s Hot 100 music chart and became the most popular song on Denny’s Exotica album (1957).1 The term Exotica has since been used to refer to the entire genre of exotic lounge music, a kitschy, Western-centric pop music that relied heavily on percussion instruments to evoke images of mysterious, far-away places. Exotic lounge music experienced a renewed popularity in the late twentieth century, and 50s Exotica, along with newly created Exotica music, can be found in most music stores today. Though Exotica sounds extremely naïve to “modern” ears and could be dismissed as a twentieth-century American fad, the genre actually brings into sharp focus a long history of cultural stereotyping and a complex relationship with “the Other,” a legacy with which today’s musicians must grapple.

Using Exotica as a touchstone, this paper explores how percussion instruments have been used in American popular music to represent non-Western cultures. Many of the questions covered—such as the fuzzy lines between cultural exchange, borrowing, and stereotyping—are perhaps even more pertinent to the genre of World Music in the current environment of globalization and cultural cross-fertilization. This essay is comprised of three parts. In Part One, by looking briefly at a number of important events in Western music history, and European history more generally, I situate Exotica within a larger context. In Part Two, I address the salient characteristics of the Exotica genre, and, more specifically, the percussion instruments used and how they function to conjure images as diverse as a busy Bangkok marketplace and a “savage ritual.” Part Three is devoted to the relationship between percussion and “the Other” in popular music today, with specific regard to World Music, a genre of which the United States is a major consumer and producer and in which, like Exotica, percussion often figures prominently. Accompanying audio examples are available at www.auntieboomboom.com, and are marked in the text as numbered audio tracks.

Part One: Background

In attempting to contextualize the Exotica genre within Western music history, it is important to look at both musical and social phenomena prior to the appearance of Exotica itself. Specifically, I find it helpful to look briefly at the history of Western appropriation of “other” musics and to situate that history within the more general context of the West’s relationships with other cultures. Just as important is to examine changes in attitudes toward this history, and we will therefore take a quick look at important events in the scholarship surrounding the relationship of West and “other.”

There are two main eras in Western music history that come to bear on Exotica. The first occurred during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period during which composers of Western classical music, such as Debussy, Stravinsky, and Bartok, were searching for new modes of expression, new sounds, and new techniques to distinguish themselves from the dominant Austro-German tradition.2 The second period began in the 1930s, another period of compositional exploration, this time centered mostly in America, in which Henry Cowell, John Cage, Lou Harrison and others were yet again attempting to discover new resources.3

Though there are instances of Western composers’ use of non-Western resources both before and after the aforementioned eras, these two periods are the most significant for 1950s Exotica, not only regarding the inclusion of non-Western sounds, especially percussion, but as regards to the perceptions of non-Western cultures as well. In order to discuss the ways in which Western composers incorporated non-Western musical elements, it is helpful to define a few terms, specifically, Orientalism, exoticism, and primitivism. In his seminal work entitled Orientalism (1978), Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said, referring specifically to the West’s relationship to the Middle East and Arab culture, argued that the East was, for the West, not a reality unfolding in another location, but an imagined “other” that functioned as a repository for all that the West was supposedly not. The West was defined by logic, intellect, technology, science, advancement, the future. The East was defined by passion, barbarism, unbridled sexuality, ancient lore, mysticism, etc.4 Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade is a typical example.

At the end of the 19th century, European composers, especially those in the cultural hub of Paris, were deeply influenced by all things Oriental, both real and imagined, in part due to the Exposition Universelle, held in Paris in 1889, in which cultures from many parts of the globe were on display. It was at the Exposition Universelle that Claude Debussy first heard Indonesian gamelan music, which was to have a significant impact on his music.5 Exoticism, for our purposes, can be thought of as a larger framework fuelled by the same impulses toward “othering” as Orientalism. However, whereas Orientalist activity creates a relationship in which the culture being represented is always an Eastern culture and the culture consuming the representation is the West, exoticism may include representations from a wider array of non-Western cultures. Works of Orientalism and exoticism tend to re-imagine ancient times and far-off lands.

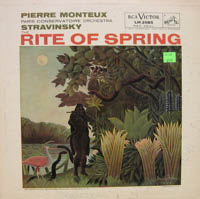

Primitivism is the tendency to ascribe to other cultures, or ancient peoples, “primal impulses” such as closeness to nature, freedom, ritualistic behavior, naivete, and free sexuality. Primitivism is, of course, also the name given to the European art movement that includes Picasso’s African period and art works by Gauguin and Rousseau, and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.6 Near the turn of the 20th century, at the height of the “Age of Imperialism,” the influence of exoticism, Orientalism, and primitivism on Western cultural production was at its peak.7

Western European countries had maintained colonies for centuries by the time of the late 1800s, so why not assign a much earlier start date to the “Age of Imperialism?” Citing research by Edward Said, Timothy D. Taylor notes in his book Beyond Exoticism, that, “By 1914, [ . . . ] Europe held a grand total of roughly 85 percent of the earth as colonies, protectorates, dependencies, dominions, and commonwealths.”8 It is astounding to think of the sheer size of such an imperialist endeavor, but also remarkable to ponder how many different cultures were living under the umbrella of European imperialism at that time in history.

In 1859, Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species, and while his research was not originally intended to be used specifically as an argument for the superiority of Western culture over other cultures, it came at a time when science in general was being hijacked to prove, in ways that seem ridiculous to us now, that, for example, Africans and females were both inferior to Western males because of the size of their skulls. Darwin’s evolutionary timeline was used to position other cultures at an evolutionary point behind what was considered the more advanced Western culture—in other words, non-Western cultures were cultures that time forgot.9

Understanding the historical framework for this period of music is the first step in relating it to the Cowell-Cage-Harrison era and to the phenomenon of Exotica. Thirty or so years after the explosion of sounds and ideas that defined the turn of the twentieth century, composers sought once again to radically broaden the possibilities for Western music composition, and once again looked to the East to do so. In addition to using found objects, extended techniques, and folklorism—meaning the use of folk idioms to expand compositional vocabulary—composers in the 1930s and thereafter were including non-Western instruments, melodic and harmonic material, and structural components in their work. John Corbett, in his essay “Experimental Oriental: New Music and Other Others,” draws a distinction between “conceptual Orientalism” and “contemporary chinoiserie.”10 To his way of thinking, for example, John Cage, in attempting to take the composer out of the composition and impose a Zen detachment on music, was practicing conceptual Orientalism, whereas, in creating an American gamelan and adopting the timbres, rhythms, and melodies of Asian musics, Lou Harrison was creating “contemporary chinoiserie.”11 For Corbett, it seems clear that there is a qualitative judgment in favor of conceptual Orientalism over contemporary chinoiserie, and he is rather dismissive of Harrison’s works. While I do not entirely agree with his assessment, I find the distinction between these two types of Orientalism useful, and it is without doubt that all of 1950s Exotica falls into the category of “contemporary chinoiserie.”

Part Two: 1950s Exotica

Flash forward to the American Exotica craze. During World War Two, many members of the American military, mostly male, had been stationed in Hawaii, the South Seas, Asia and elsewhere, and had had some experience, if usually quite limited, with one or more of the cultures situated in these vast geographical regions. In addition, the post-war 50s were a time of economic prosperity, in which more Americans could afford to travel. Circa 1920, Cuba had been the prime vacation destination for many Americans due to its close proximity and its permissive attitude toward many things, alcohol included, that were banned in the US. However, in the late 1950s, Cuba was in a state of upheaval and no longer served as the island playground it had once been. In 1959, statehood was conferred upon the Hawaiian islands, and investors from the mainland were eager to develop it into a thriving tourist destination. Each of these threads—military cultural interactions during World War Two, American tourism in Cuba, and Hawaii’s journey to statehood—are fascinating and complex, and worth much more consideration than is possible within the scope of this paper. Taken as a whole, they were to have a profound influence on the production, packaging, and reception of Exotica.

There is a rather small cast of characters in the Exotica story. The two main players are Les Baxter and Martin Denny, and they are related by virtue of one of Exotica’s signature songs, “Quiet Village.” Les Baxter composed and recorded the song, and Martin Denny’s subsequent arrangement of it included the first use of bird calls (made by members of the band), which became a Denny trademark and a distinguishing characteristic of Exotica. Les Baxter was a classically trained pianist who, before launching a career as an arranger and conductor for Capitol records, had also worked as a singer with Mel Torme’s Mel-Tones and had formed his own vocal group, “Les Baxter’s Balladeers.”12 Once at Capitol, Les worked with Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, and Arthur Murray, among others. By today’s standards, he had an incredible amount of freedom at the record label, and by the end of his career had put out over 50 albums, not to mention having composed soundtracks to many Hollywood films, mostly “B” movies.13 By his own admission, it was in Baxter’s nature to do “weird stuff,”14 and his experiments were not limited to Exotica. His first album, Music Out of the Moon, on which he used a theremin, was a pivotal recording in yet another branch of lounge music that is generally known as “Space Age Pop.” Baxter was well aware of the early 20th century classical composers and was greatly influenced by Debussy and especially Igor Stravinsky, a fact that is reflected in the title and musical content of one of his most important Exotica works, Le Sacre du Sauvage, better known as Ritual of the Savage.

Martin Denny, also a classically trained pianist, spent several years touring South America early in his career and related how that early exposure to South American rhythms contributed heavily to his lifelong love of Latin American rhythms in general.15 Denny first went to Hawaii in 1954 at the invitation of Don the Beachcomber, and spent time playing piano at the bar in Don’s establishment. By 1956, he had formed a four-piece combo of piano, bass, vibes, and percussion, and was performing nightly at the Shell Bar in the Hawaiian Village Hotel.16 In the afore-mentioned interview, Denny recalls how he began to employ bird calls, made by the members of his band:

The Hawaiian Village was a beautiful open-air tropical setting. There was a pond with some very large bull frogs right next to the bandstand. One night we were playing a certain song and I could hear the frogs going “Rivet, rivet, rivet.” When we stopped playing, the frogs stopped croaking. I thought, “Hmm—is that a coincidence?” So a little while later I said, “Let’s repeat that tune,” and sure enough the frogs started croaking again. And as a gag, some of the guys spontaneously started doing these bird calls. Afterwards we all had a good laugh: “Hey, that was fun!” But the following day one of the guests came up and said, “Mr. Denny, you know that song you did with the birds and the frogs? Can you do that again?” I said, “What are you talking about?”—then it dawned on me he’d thought that was part of the arrangement. At the next rehearsal I said, “Okay, fellas, how about if each one of you does a different bird call? I’ll do the frog . . . ” (I had this grooved cylindrical gourd called a guiro, and by holding it up to the microphone and rubbing a pencil in the grooves, it sounded like a frog). We played it the next night, and all evening people kept coming up and saying, “We want to hear the one with the frogs and the birds again!” We must have played that tune thirty times. It turned out to be Quiet Village.17

So there were two kings of Exotica, Baxter in Hollywood and Denny in Hawaii, the former generally composing for full orchestra, the latter composing or arranging for his four-piece combo. Each had an appetite for incorporating the unusual into his music. Together they would contribute the lion’s share of the entire Exotica genre and would prove highly influential to the other groups who latched on to the Exotica sound.

Audio Track 1: Excerpt from Martin Denny’s version of “Quiet Village”

Denny’s use of vibraphone in the lineup was modeled on the piano/vibes combination used by George Shearing in his small combos, and, more importantly to our discussion, Denny has said that he used the soft sound of the vibraphone as a nod to traditional Hawaiian music, specifically slack-key guitar.18

The percussion here is used in several different ways. The vibes come in as a soft, smooth, and lush melodic instrument, taking over from the deeper, more insistent piano. For Exotica composers, the vibraphone is the ultimate instrument for conjuring images of the soft side of tropical island life: gently blowing breezes, waves softly lapping the shore; the sweet, delicate scent of plumeria and gardenia, perhaps the softly swaying hips of an island beauty. There is a less romantic reason for the ubiquitous use of the vibraphone, however: When Martin Denny formed his group and chose to include vibraphone, he hired Hawaiian-born vibraphonist Arthur Lyman. Lyman later went on to form his own Exotica combo, The Arthur Lyman Group, and, being the main composer and arranger for the group, featured his own instrument heavily in the bulk of his repertoire. After Denny, Lyman was the next-biggest-selling Hawaiian-based Exotica artist and, given that Denny continued his group with a new vibes player, the genre was very vibes-heavy. Aside from the vibraphone, the percussion in “Quiet Village” consists of bongos, güiro, and suspended cymbal, all of which serve to propel the music forward. The güiro also serves as frog sound effect, an extended technique that would be right at home in a George Crumb piece.

Figure 1.

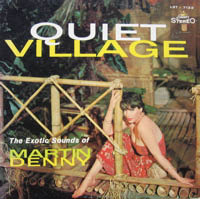

The title “Quiet Village” leaves to the listener’s imagination specifics regarding location and inhabitants. As was true with some works of the early twentieth century, the lack of specificity here is intentional. The quiet village is somewhere distant, away from the kids, the suburbs, the 9-to-5 job. The listener may insert himself into the scene with the cute little dish in the primitive hut. As seen in Figure 1, the cover of “Quiet Village” boasts “exotic sounds.” Looking straight at the camera is a barefoot, bangled, big-breasted woman, looking primitive only in the most modern of ways, who seems to be saying either “C’mon in, big fella” or, “If you want to get into my grass shack you’ll have to wrestle me first.” Either way, the gazer comes out a winner. It seems clear from the cover that the target audience is male, and this is confirmed by the liner notes, written by John Sturges, director of such movies as Gun Fight at the OK Corral and Bad Day at Black Rock. Inviting the reader to become one of the “in crowd,” Sturges writes “ . . . after you’ve asked, “How long has this been going on, how did I miss it, has he recorded other stuff as terrific as this . . . you have become a full-fledged member of his fan club. Welcome, brother.” And just so you are sure it is a club you really want to belong to, he continues: “Maybe you’ve wondered what-in-the-world kind of fellow is he to have cooked up these fantastic sounds. Maybe you have in mind a pale, aesthetic type who flutters his hands and uses mystic four-hundred-dollar words to describe what he is doing. Surprise…he’s a great big husky guy who looks like he could make bow knots out of iron bars.”19 The implication here seems to be that if you liked the music of an intellectual, effeminate man, you would be one, too.

The image of a sexy woman alone in a tropical paradise, who may or may not resemble a native Hawaiian or other islander, was used on many Exotica album covers. All of Martin Denny’s early albums used the same model, Sandy Warner, done up in various exotic ways. In addition, as mentioned earlier, some of the marketing was geared specifically toward increasing the tourist trade in Hawaii, and airlines such as TWA and Hawaiian, sometimes in conjunction with larger hotels, produced elaborate keepsake record albums, also with a lone young female on the cover.

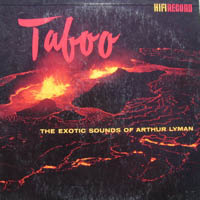

The other side of a natural paradise, of course, is that it is volatile and untamed. It is all fine and good to frolic with the native girl in the jungle until the huge volcano erupts, and then you’re running for your life. Some album covers sought to promote Exotica as the logical soundtrack to the primitive—either nature itself, or the primitive within--preferably at its most volatile. For Arthur Lyman, lava was the substance of choice:

Figure 2.

Audio Track 2: Excerpt from Lyman’s song “Taboo”

Underneath a wooden flute, we hear boobams, which are bamboo tubes with skin heads, and we also hear quijada (or donkey’s jaw), and congas. Exotica composers made extensive use of instruments not typically found in Western orchestral music, such as rattles, conch shells, bamboo flutes, wind chimes made of shells or bamboo, log drums and boobams, etc. These instruments could hypothetically be fashioned using natural materials in a jungle setting. Whether or not they actually existed in “primitive cultures,” such instruments could aurally suggest such a culture through the simplicity of their sound.

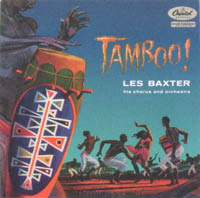

Another concept closely associated with Exotica is that of savagery, of humans acting with wild abandon, often under the spell of hypnotic music and/or some ancient god. In terms of packaging, Les Baxter’s covers provide the best examples of this.

Figure 3.

The cover of Tamboo! is a textbook example of the construction of an “Other.” Though Les Baxter’s name appears directly under the word “Tamboo!,” he himself would look more than a little out of place in the scene depicted. If you listen to this album, the cover seems to suggest, you can get a peek into this strange and forbidden world. The titles on the album are very specific: “Havana,” “Rio,” “Tehran,” “Oasis of Dakhla.” However, with place names from the Caribbean, South America, the Middle East, North Africa, East Africa, and more, it is hard to pin down where or what that forbidden world actually is.

Having conducted research on folkloric music in the Caribbean, I know that there are both drums and dance styles in various parts of the region that are called tambú, and that both were brought to the region by slaves from Africa. However, it is also certain that tambú did not exist in all the regions covered, at least by place name, on Baxter’s album. One can only conclude, therefore, that the word “Tamboo!,” along with the image on the album cover, is a sort of shorthand for wild ritual dances done by darker-skinned people the world over—in other words, “them.”

The mixing of diverse cultures does not end at the cover. In the following excerpt from the song entitled “Tehran,” Baxter employs the percussion instruments that are instant cues for the Middle East in Exotica: finger cymbals and a high-pitched, dumbek-like drum (possibly a bongo, in this case).

Audio Track 3: Excerpt from Les Baxter's song "Tehran"

Later in the song, however, the Middle East takes a strange turn into a typical Afro-Cuban groove

Audio Track 4: Excerpt from Les Baxter's song "Tehran"

This is not the first sound you would expect to find in Tehran. In the song “Quiet Village,” Martin Denny also relied on instruments typically used in Afro-Cuban music. In truth, a huge number of Exotica songs rely at least in part on Afro-Cuban rhythms and instruments. Part of the reason for this, as mentioned earlier, is that Cuba and Cuban music were already familiar to Americans due to heavy tourism in Cuba in earlier decades. Also, from the 40s forward, Latin jazz and Latin dances had become immensely popular here in the US.

As mentioned earlier, as a way of conjuring ideas of savagery, Exotica album covers often employ imagery that suggests the presence of an ancient and frightening god, depicted by an idol, the tiki.

Figure 4.

The word “tiki,” in Polynesian, means “first man,” and tiki sculptures are traditionally large, usually wooden images of the creator-ancestor of Polynesians. In Exotica, however, tikis and other idols from Incan and Aztec cultures are all used to represent ancient mysteries, magic, and lands that time forgot.20

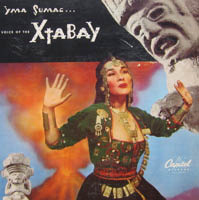

The next image is the cover for an album by Yma Sumac, with music co-composed and arranged by Les Baxter:

Figure 5.

Yma Sumac, as the liner notes would have it, is “The Voice of the Xtabay,” “the bird who became a woman.” The Xtabay, according to ancient legend, is “the most elusive of all women . . . Her voice calls to you in every whisper of the wind . . . you follow the call of the Xtabay . . . though you walk alone through all your days.”21 The Xtabay may have power over you, but, from the look of the cover, the stone gods have power over her.

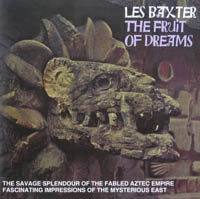

Les Baxter’s album The Fruit of Dreams, shows a stone idol that represents, “the savage splendour of the fabled Aztec empire.”22

Figure 6.

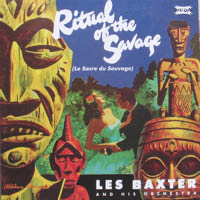

And here, on one of Les Baxter’s most famous albums, the one whose title gives a nod to Stravinsky, is one of the most interesting depictions of savagery:

Figure 7.

A group of rather menacing tikis surrounds a couple that looks as though they are taking a break from a cotillion. The gentleman looks to be forcing himself on the lady, who is resisting. And herein, it seems, lies the real ritual of the savage.

Audio Track 5 contains an excerpt from the song “Jungle River Boat,” which, although lighter on percussion than the rest, once again uses the vibraphone as a cue for the banks of a lush environment. It also features one of my favorite Exotica techniques, vocalise (wordless singing), heavy on the soprano. As we near the end of the “Jungle River Boat” ride, we seem to pass by, once again, the village where the Afro-Cubans live. The Exotica composers may have relied so heavily on Afro-Cuban and other Latin beats because they provided a reliable way to enliven the music. This assumption seems born out by a quote from a magazine interview with Martin Denny, in which he says, “If you take Hawaiian music alone, it lulls you to sleep—whereas Latin has exciting rhythms; it has a beat!”23 The aim, it seems, was to spice up the sleepy sound, rather than to imply that all cultures other than Western ones use these particular instruments and beats. However, it is clear that Exotica falls into the trap of using traditional cultural production from other regions to reinforce stereotypes about non-Western cultures, thereby also reinforcing the West’s idea of itself as a superior, more advanced culture, one that observes the habits of other cultures in the same Darwinian way it observes those of the animal world.

Audio Track 5: Excerpt from the song “Jungle River Boat”

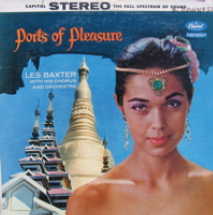

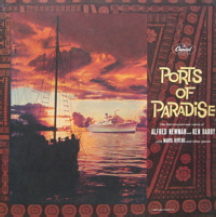

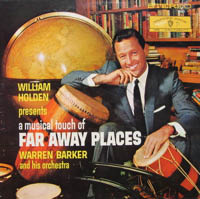

A number of Exotica albums focus not on recreating the environment of a tropical island, but on the Westerner as explorer, touring far-flung lands in every corner of the globe. With titles such as Ports of Pleasure, Ports of Paradise, and A Musical Touch of Faraway Places, these albums promised not languid escape but adventure, risk, and a cultural smorgasbord.

Figure 8a.

Figure 8b.

Figure 9.

The cover in Figure 9 shows movie star William Holden in front of a library, with a huge globe at his side, and percussion instruments of all sorts at his feet. A Musical Touch of Faraway Places is a concept album of sorts, for which songs were created based on instruments that Holden collected on his travels during movie shoots. Each track on the record is devoted to a specific locale—Malaysia, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Java, India, the Philippine Islands—and the liner notes go track-by-track, giving a taste of each spot. The notes to the first track, “Malayan Nightbird,” mention right away that the song “is notable for its reliance on musical sounds (as on all the tracks in this album) to produce the atmospheric effects of its locale and subject. Here the nightbird’s cry is simulated on the xylophone.”24

The notes to Les Baxter’s Ports of Pleasure are, not surprisingly, even more fanciful. Like the previous album, Ports of Pleasure has tracks for specific destinations, including Bombay, Saigon, Bali, Singapore, and Shanghai. The two tracks that refer to the Middle East are called “City of Veils” and “Harem Silks from Bombay.” The text for the latter reads “Freighters from Bombay carry rich silks and another, more beautiful cargo—slave girls for wealthy princes of the East.” Next to the text for “City of Veils,” there is a tiny picture of a veiled Middle-Eastern woman, presumably a harem girl, and behind her sits a Middle Eastern man in traditional dress. The text is seductive:

Within the city’s crumbling walls, the visitor from the West is enticed by the sensuous movements of veiled dancers, unaware of the intrigue that pulses inside the city, veiled from him by whispering voices, by shuttered windows and silent footsteps.25

In these records percussion instruments again are used to reinforce Western stereotypes of specific non-Western cultures. In “City of Veils” we hear an orchestral intro full of roaring timpani, snare drum, and bass drum, climaxing in a 3-3-2 rhythmic pattern, which then dissolves, giving way to finger cymbals, sistrums, a drum struck with rattan, and bells, at which point, presumably, we’ve reached the veiled dancers.

Audio Track 6: Except from “City of Veils”

And that is the mysterious Middle East, neatly packaged. The “port”-style records always include one or two songs with titles like “Tokyo Trolley,” “Hong Kong Cable Car,” and “Shanghai Rickshaw,” and the instruments used are predictable. In the excerpt from “Junk City Hong Kong,” we hear a good example of the way percussion is used to reinforce the stereotype of the bustling Asian metropolis. When the subject is China or Japan, xylophone, temple blocks, and tam-tam are always present, the xylophone and blocks usually used in a staccato rhythm, punctuated by dramatic tam-tam strokes.26

Audio Track 7: Excerpt from “Junk City Hong Kong”

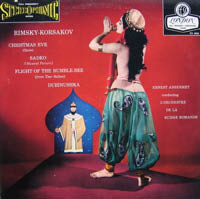

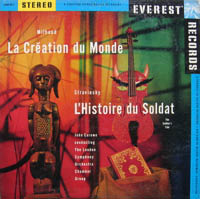

I have dwelt a long time on the packaging of Exotica and, in concluding this section, I include below the cover art from a few 1950s recordings of Western classical favorites. While the music contained in these albums is clearly of a more serious nature than Exotica, it is fascinating that the same harem girls, primitive idols, and savage jungles were used to sell these compositions as well.

Figure 10a.

Figure 10b.

Figure 10c.

As mentioned earlier, the 1930s saw the beginning of the second major wave of exoticism in Western classical music, in which Cowell, Cage, Harrison, and others were exploring non-Western musical resources, especially percussion. This era produced Exotica’s art music cousins. If you have heard or performed any of the percussion ensemble repertoire of that time, such as Carlos Chavez’ Toccata, Cage’s Constructions, Harrison’s Canticle #3, Cowell’s Ostinato Pianissimo, etc., you will hear similarities with Exotica in the types of non-Western instruments used. Also, early percussion ensemble repertoire contains many examples of the combination of typical Western instruments, such as piano and vibraphone, with more “primitive” ones that was a signature sound for Exotica groups.

Martin Denny had an enviable collection of percussion instruments from around the world. His friends were on notice to bring him any unusual percussion instrument whenever they traveled.27 When he was given a new instrument, he would build an arrangement around it. I have heard a similar—possibly apocryphal—anecdote, about John Cage’s composition of Third Construction, in which he purportedly took all the instruments from around the world that he had collected or been given, and gave some of each to each of the four players. Whether or not this is true, the two composers’ friends must have traveled to some of the same places. It is without doubt, though, that Cage and his peers were striving not for simple novelty but for deep changes in the direction of music.

Part Three: We Are The World?

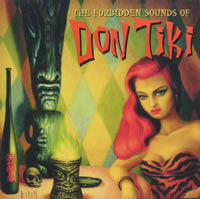

Figure 11.

As I mentioned earlier, Exotica experienced renewed popularity in the 1990s, and a new tiki culture fad appeared. In addition to the reissue of many Exotica recordings from the 1950s and 1960s, several new Exotica bands formed and put out CDs. One such group is Don Tiki, based in Hawaii. Don Tiki has put out a number of CDs and, as you can see from Figure 11, has adopted not only the Exotica musical style but the aesthetic as well. However, there are a number of interesting differences between Don Tiki’s Exotica and the original. There is still a woman on the cover of the disc, and she is still looking directly out at us, but her look seems more challenging than inviting, as though she might just throw her flaming drink in the gazer’s face. There are a number of Don Tiki songs that feature lyrics, rather than the more typical “oohs” and “ahhs,” and some of the lyrics turn the old gender roles upside down, as in the song “An Occasional Man,” in which female vocalist Hai Jung Aholelei sings the following:

Don Tiki has updated Exotica somewhat, subtracting some of the less attractive racial and gender stereotypes from both the aesthetic and musical realms. This album was issued shortly before Martin Denny died, and Denny not only performs on it, but two of his compositions are featured as well. On Audio Track 8 (www.auntieboomboom.com, 8), an excerpt from an original composition by the Don Tiki group called “Barbi in Bali,” we hear a Balinese gamelan introduction, to which bongos and güiro are added. Eventually, we have a funky group that includes organ, harpsichord, marimba, flute, and vocals. One of the successes of the Don Tiki endeavor, I find, is that the group manages to emphasize the most interesting aspects of exoticism, such as heavy use of percussion, and new combinations of instruments and timbres from different cultures, while avoiding the cultural hierarchy that we hear in the older recordings.

Audio Track 8: Excerpt from Don Tiki's “Barbi in Bali”

In his book Beyond Exoticism, Timothy Taylor has a fascinating chapter on World Music as used in television advertising. The World Music we speak of here is not associated with a particular place or culture or group of people. Like Exotica, it is simply “foreign” sounding. Taylor interviewed executives from several advertising agencies and uncovered some surprising facts about TV ad soundtracks—ads used to sell all manner of things, but especially, and not surprisingly, travel. What he finds is that, contrary to the title of his book, we are not beyond exoticism at all. The same techniques used by Exotica artists in the 1950s to conjure up appealing, but often intentionally vague, foreign lands, peoples, and cultures are used today to sell the idea that an airline or cruise ship or car can give us the freedom and power to sneak an intimate peek at the primitive, the savage, the childlike, the erotic that’s “out there.” And who is sneaking the peek? The images in the ads most often show white couples encountering darker-skinned “natives,” who are in the midst of living their simple, natural lives.28

One may ask, “what is the harm in this?” You sell a few cars, maybe perpetuate a few stereotypes, but it is not about anybody specific, so who can it actually hurt? If we limit the argument to a turn-of-the-century movement involving a few Western composers, or a 1950s American fad music, or a series of contemporary TV ads, it might not seem to amount to much. If, however, we expand our view to include all of these phenomena and link them to our economic and political relationships with individual cultures throughout the world, there begins to emerge a disturbing pattern of deep errors of perception with regard to other cultures over decades and even centuries. The current Western (primarily American) military and political involvement in the Middle East is inextricably linked to, and a continuation of, the Western relationship with “the Orient,” and “the East,” and, no matter what our individual opinions regarding that involvement may be, it seems critical that we be aware of the history that brought us to this point. There is, of course, a lot of World Music being generated that is born not of a need to sell anything, but of a genuine desire on the part of musicians to work with musicians from other places and enjoy the interaction and the sharing of ideas. However, even this type of interaction is best approached with a clear understanding of the West’s complex history in relation to other cultures.

As I hope I have made clear, today these questions are even more pertinent and more complex. In one way or another, most if not all of us will find ourselves in some relationship with “World Music” and with conceptions of “the Other,” whether it be performing Debussy’s music, listening to Buena Vista Social Club, being asked at a gig or recording session to “play something ethnic,” collaborating with a musician from a non-Western culture, or, conversely, being a musician from a non-Western culture and collaborating with a Western artist.

Not surprisingly, many of the vexing questions surrounding World Music mirror larger issues facing the cultures of the globe today—questions such as: Who has the right to claim ownership of, determine the use of, document, or profit from a particular form of (cultural) production? Who has the right to define a particular tradition? Should inter-cultural interaction or cultural borrowing carry with it responsibilities? When determining how to answer such questions, knowing that they will in all likelihood never be fully resolved, the mistakes and successes of past generations seem highly relevant.

Bibliography

Berger, John and Helen Altonn. “Pioneer of ‘Exotica’ Music Captivated Audiences Worldwide.” The Honolulu Star Bulletin. http://starbulletin.com/2005/03/04/news/story3.html (accessed June 6, 2007).

Cooke, Mervyn. “‘The East in the West’: Evocations of Gamelan in Western Music.” In The Exotic in Western Music, edited by Jonathan Bellman, 258-80. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998, p. 259.

Corbett, John. “Experimental Oriental: New Music and Other Others.” In Western Music and Its Others, edited by Georgina Born and David Hesmondhalgh, 163-86. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000.

Darby, Ken. Brochure notes for Alfred Newman and Ken Darby, Ports of Paradise. Capitol Records STAO-1447.

Denny, Martin. Interview. In Incredibly Strange Music. Vol. 1. Edited by Andrea Juno and V. Vale, 142-51. San Francisco: Re/Search Publications, 1993.

Fichera, Al. Brochure notes for Les Baxter, Tamboo!/Skins. Collectables Records COL-CD-2782.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.

Sturges, John. Liner notes for Martin Denny, Quiet Village. Liberty Records LST 7122.

Taylor, Laura. Brochure notes for Les Baxter, Ritual of the Savage. Rev-ola CR REV 171.

Taylor, Timothy D. Beyond Exoticism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

Endnotes

1Berger and Altonn, “Pioneer.”

6Encyclopedia Britannica 2008. “Western Music.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. http://www.britannica.com/bps/topic/398976/Western-music (accessed February 2, 2008).

7Taylor, Beyond Exoticism, 75.

10Corbett, “Experimental Oriental,” 170-71.

21Liner notes for Yma Sumac, Voice of the Xtabay, Capitol Records CD 244.

22Brochure notes for Les Baxter, The Fruit of Dreams, él Records ACMEM 57CD.

24Liner notes for Warren Barker and his orchestra, A Musical Touch of Faraway Places, Warner Bros. WS 1308.

25Liner notes for Les Baxter, Ports of Pleasure, Capitol Records ST 868.

26Because my focus is on the role of percussion in Exotica, I have not delved into the significance of the genre’s melodic and harmonic language, but, speaking very generally, these aspects of the music are similarly codified by region. One obvious example is the use of pentatonic scales for anything Asian, and the use of the lowered second, as in a Phrygian scale, for anything Middle Eastern.