This article was originally part of a Round Table discussion entitled Four Approaches to the Understanding of a Single Musical WorkThe Aria "Ich folge dir gleichfalls" from the St. John Passion of J.S. Bach, which took place at the seventh annual meeting of the Society held in Washington, D.C., December 28-30, 1964.

The other participants were Arthur Mendel, Donald J. Grout, and Edward A. Lippman. Their articles also appear in SYMPOSIUM Volume 5.

If, as I believe, structural analysis represents on the one hand ideally. sharpened hearing and on the other a guide to performance, it follows that it cannot be profitably undertaken without at least token study of the historical provenance of the work in question. For how can we accurately hear and perform a composition whose conventions are unknown to us? As Kenneth Burke has pointed out, using the term in its broadest sense, conventional form is one of the most important guides to the understanding of a work of art, since it tells us what we may reasonably expect of it. Even when it temporarily deceives us, conventional form functions negatively by deliberately arousing false expectations. Gombrich comes to a similar conclusion from a somewhat different direction when he states that we cannot possibly understand what an artist is up to unless we are familiar with the range of choices open to him.

Such historical considerations can also save the analyst a lot of time. The more characteristics of a composition he can establish as standard practice the more attention he can devote to its really interesting aspects: those that are perhaps unique for the individual work. Although a dominant seventh in Palestrina may well call for a lengthy explanation, in Mozart such a chord usually needs no special mention. What interests us in this composer is rather the opening of the C major Quartet.

I shall accordingly waste no time establishing that Ich folge dir is in B flat major; nor shall I marvel that its first modulation is to the dominant. I shall assume that a more or less Schenker-like outline can be successfully extracted from the piece, and I shall use one to the extent that I find it helpful.

With respect to the general layout, there is certainly nothing unusual about the flute obbligato, the resulting trio-like texture, the ritornello statement at the beginning, and the Devise technique by which the voice enters. These points might well lead one hearing the aria for the first time to assume a standard Da Capo, a guess further supported by the cadence in the dominant and the reprise of the ritornello in that key, but soon discredited by the next phrase, with its new words and turn toward the submediant. The form that in fact emerges is one loosely referred to by both Neumann and Dürr as a "free Da Capo" form. Although not every example cited in Neumann's Handbuch follows the present pattern, there are about a hundred Bach arias that do, scattered throughout the cantatas, the masses, the oratorios, and the passions. The norm established by these is clear: an opening section, modulating usually to the dominant (or, if in minor, to the relative major); a middle section with new words and new music, cadencing in one or more related keys; and a reprise of the opening, both verbal and musical, but now of course coming to rest on the tonic.

Now, whereas the resemblances between the aria and the baroque concerto have often been pointed out, what interests me about this free Da Capo is its connection with the classical concerto. The opening ritornello in the tonic, the solo exposition developing the same material but moving to the dominant, the placing of further ritornelli, the eventual tonic recapitulation—these are common to both forms. And if, as in the present example, there are distinct parallels between the later sections of exposition and recapitulation (compare m. 29 ff. with m. 129 ff.), the aria approaches the classical model very closely indeed—or rather, Mozart's concerto-form essentially expands the earlier model.

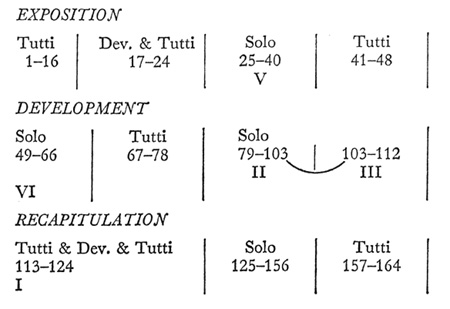

All this, however, is still completely general and for that reason primarily historical. As an analyst my interest in Ich folge dir is more likely to be stimulated by its individuality—by some point of difficulty or some variation from the expected. Now, I do not have to look far to find such a deviation. It is already evident in Fig. 1, which presents a rough outline of the pattern so far discussed.

Figure 1.

I refer, of course, to the passage at the end of the development (to use sonata-form terminology) where a cadence on II is followed within ten measures by one on III. This progression, striking enough in itself, is made even more so by the elision joining the two phrases. Although there are other elisions in the piece, this is the only occurrence at a perfect cadence (for I do not consider m. 66 as an elision; the entrance of the flute is introductory to the next phrase). Furthermore, and consequently, this is the only occasion on which the voice continues after making such a cadence, all the others being punctuated by tutti.

The passage in question is, then, unique in the context of the piece and certainly striking enough to arouse analytical interest. More than that: a little research reveals that it is almost unique among Bach's arias in this form. I do not claim to have located them all, but I have looked at as many examples in major keys as I could find—over fifty. (Examples in minor would not be relevant, for obvious reasons.) By far the commonest succession of perfect cadences is I-V-VI-III-I or some variation thereof: either VI or III may be omitted, or the two may be reversed. When II occurs it is most often between V and VI. Very rarely is it associated with III, and in no other case did I find it between VI and III. The present example thus seems to present a unique variation, and it is the interpolation of the cadence on II that the analyst must attack.

It is often the case, in Bach as in other composers, that the important developments of a composition can be shown to be expansions of striking events of the opening measures. In a fugue, for example, an examination of the subject alone may often yield a clue to the course of the coming modulations. In Ich folge dir the obvious place to look for such a key is the opening ritornello. The formal layout of these sixteen measures is roughly that of four 4-measure phrases. But the second and third phrases (m. 5-12) are closely joined together in a larger unit heard as an expansion of the appoggiatura motif D-C of m. 4. That this forms a developmental interpolation in a simple 8-measure period is immediately made clear by its omission from the repetition of the theme in m. 17-24.

It is interesting that the original version of m. 4 made its motivic connection with the next measure even more obvious—perhaps so obvious as to obscure the fact that m. 5 does indeed begin a new phrase. The final version—which is applied at every corresponding point throughout the work—clinches the important half cadence. Another point to notice is the role of the bass-rhythm in clarifying the phrase-divisions and melodic functions. The presence of the downbeat in m. 9-12, in contrast to what precedes and follows, emphasizes both the four-measure pattern and the increased melodic importance of the first beat: what was only a decoration in m. 5-8 now, in the descending line, becomes a more integral element. I stress this because one can find, throughout the piece, passages where Bach made changes in the bass-rhythm to point up phrase-groupings, melodic accents, or cadences (e.g., m. 36-38, 91).

Fig. 2a is a sketch of the voice-leading of the ritornello in which the rhythmic values very roughly correspond—one quarter-note to the measure—to the relative durations, actual or implied, of the score.

Figure 2.

This outline can in turn be simplified in several ways. First (Fig. 2b), the melody can be heard as a preliminary rise to the fifth degree, F, followed by a stepwise descent to the second, C, in m. 4. The interpolation then expands the last half of this descent, 3-2, and the final phrase completes the line 3-2-1. If we grant this as the controlling pattern, we can nevertheless also hear a subsidiary one (Fig. 2c) unifying the first twelve measures as an expansion of the first phrase. G, as the neighbor to F, now assumes special importance, harmonically signalized by the turn to the subdominant in m. 8. But if we take the last phrase rather than the first as the one determining the line, we can easily come to hear the section as primarily outlining the interval of a third (Fig. 2d). And finally, if we listen to the harmony, we cannot fail to be struck by the persistence of the tonic as a pedal in various voices—a persistence melodically underlined by the version given to the voice when it enters. It is then not far-fetched to hear the section as representing the tonic, alternating with neighbors (Fig. 2e).

Which of these interpretations is borne out by the rest of the aria? It is my contention that all of them are. The descent of the fifth seems to me to control the structure in the large, and especially in the middle of the aria we find F and its neighbor G strongly emphasized. At the beginning, however, the tonic predominates; and toward the end, the descent from the third. And is not this shift of control to a certain extent a reflection in the large of the order of events in the opening statement? In fact, one of the most interesting details about that statement is the delay in the emphasis of the third. In m. 4 it is clearly an appoggiatura to the second degree, and this relationship is expanded in m. 5-12; not until m. 13 is 3 given tonic support. Now it is indeed 3 that is sustained, and 2 that is postponed until the last possible moment. Harmonically, as well, the third degree is now given prominence. The cadence formula represented by the bracketed bass motif in Fig. 2a has of course been adumbrated from the beginning—this being one reason for the revision of the bass line in m. 2. (Another is the need for giving stronger tonic support to the F.) In the last phrase the bass motif is stated more frankly, with an implied doubling at the third, the octave, and the tenth, that even outlines the mediant triad.

To summarize, we hear a line beginning on 1 and rising to 5, which is decorated by a neighboring 6. The descent to the tonic is interrupted at 2. Only then is 3 given its due weight, after which the descent to 1 is rapidly completed. But this is precisely what is stated in harmonic terms by the series of cadences outlined in Fig. 1! If I am right, the sequence of modulations represents a harmonic augmentation of the elementary melodic motion.

If at this point you are ready to accuse me of analytical sleight of hand, let me hasten to point out that the technique exemplified here is by no means uncommon. A simple instance that we are all familiar with is to be found in the Scherzo of Beethoven's Sonata Op. 2 No. 2. The melodic line of the opening period moves, oddly enough, from tonic to leadingtone and back. And to what key does the composer modulate for the principal episode of the second part? To the key of VII! Such a modulation in a short movement in a major key is so rare in Beethoven as to require special explanation; here, as in the Bach aria, that explanation is to be found in the opening melodic statement.

Fig. 3 attempts to show how the motion of the ritornello is expanded melodically throughout the entire piece.

Figure 3.

In this outline the letters A, B, C, represent thematic repetitions. It should be noted that these repetitions are not in every case attached to the same melodic outline: compare, for example, the first statement with those of m. 67-78 and m. 86-103. In the first case my justification is the octave transference between B and C; in the second, it is the influence of the vocal line, which reduces the thematic repetition in the flute to the status of a discant. And it is the essential direction of the vocal line, rather than its detail, that explains why the cadences on VI (m. 64) and III (m. 110) are shown as ending melodically on the fifth. All the perfect cadences, it should be mentioned, are united by the bass, which in each case presents some variation of the original formula of m. 13-16. (The preservation of this formula is probably another motivation of revisions in the bass-line.)

The half-notes in Fig. 3 indicate what I consider to be the controlling line, which, in augmentation of the opening melody, rises stepwise from 1 to 5. Here it pauses to emphasize the neighboring G before descending to C. The recapitulation now expands the opening statement in such a way as to develop the melodic prominence of 3. I hear this degree, in fact, as already dominating the preliminary reprise of m. 113-24, following as it does the mediant cadence. From m. 125 on, although the voice-part is still primary, the outline is a composite drawn from both voice and flute. This enables me to incorporate quite a bit of detail in order to show how the expansion is derived. What sets this development in motion turns out to be a diminution of the crucial descent to the cadences on II and III (see the brackets marked NB). The superiority of the revised version is due to its continuation of just this descending line and to its consequent avoidance of premature emphasis on the climactic G. The result is a tonicization of the subdominant by a line down to E flat that neatly inverts the one ascending to F to establish the key of the dominant in the exposition.

I shall not strain your credulity by asking you to accept as anything more than a coincidence the fact that the melodic descent from C to A in m. 103-110, followed by the return to B flat, augments the final melodic turn of the ritornello (although, to go a little further in this direction, one might consider the relevance of an outline combining Fig. 2, d and e). But one detail that does deserve mention is the remarkable way in which the second degree is slighted in the final vocal cadences. At m. 152 the C appears only in the flute; at m. 156 it is sung, but as an appoggiatura that did not even appear in the original version. Here, then, is one more reminder of the peculiar relation of 2 to 3 that we have found characteristic of this piece from the outset. As a result, the dominant of m. 155 has more than a little feeling of III, so that it is possible to hear the deceptive cadence as initiating a progression that briefly recapitulates the V-VI-II-III-I that has governed the course of the entire aria. (This technique of harmonic summary is another one whose use is widespread. I need mention only the way that Schubert, in the Adagio of his 'Cello Quintet, strikingly introduces into the final cadence the minor Neapolitan that has already furnished his principal key-contract.)

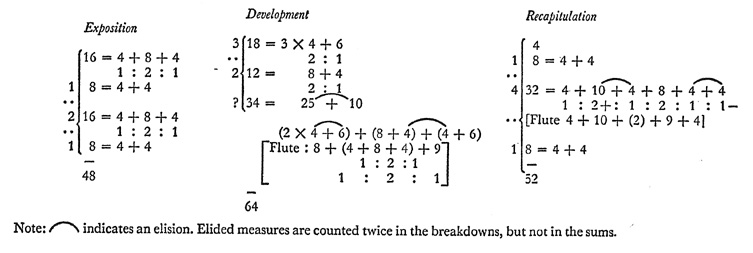

So far I have said little about rhythmic detail or general proportions. A natural question arises as to whether one can discover any influence of the ritornello in this area. If, in spite of the temptation to divide this section into four equal phrases, we hear m. 5-12 as bound together in a single developmental group, we find established a ratio of 4:8:4 or 1:2:1. A similar articulation seems appropriate to the exposition proper, m. 25-40; and if we view this period as framed by the Devise-period and the dominant ritornello, then for the entire section m. 17-48 we find another perfect 1:2:1, now of thirty-two measures.

The developmental nature of the middle section will be obvious if we look first at the ritornello of m. 67-78, which, using only the material I have called B and C, thus exhibits the truncated ratio of 8:4 or 2:1. But this has already been heard in a slightly more complicated fashion in the preceding section, m. 49-66, which presents three 4-measure groups followed by one of six measures. This last group presents the first overt reference to units of three measures or multiples thereof—and in fact, with its suggestion of a hemiola cadence, to even more complex triple units.

The passage just discussed also makes the first step toward the rhythmic independence of the flute, which becomes much more nearly complete in the next section, m. 79-112. Here it is much the simpler part: beginning one measure late, it divides into 8:16:9, again almost an exact 1:2:1, of which the central portion is a transposition of the complete ritornello and hence also 1:2:1. At the same time, the voice exhibits a complex design: two 4-measure groups that elide with the following 6-measure group, then twelve measures (8 + 4, with a suggested hemiola) that elide with ten (4 + 6, with another hemiola).

The rhythmic complication of the development is a reflection of the linear and harmonic situation already discussed at length. Its general proportions, too, are interesting from this point of view. Typically less exact than those of either the exposition or, as we shall see, the recapitulation, they combine twos and threes in an approximate 3:2:6 that, but for the final extension, would have been an almost perfect 3:2:4.

A return to four-square phrasing in the recapitulation parallels the umambiguous return to the home key. But there is subtlety even here in the gradual approach to the tonic. Of the three statements of phrase A, the first (m. 113) has no bass on its first downbeat; the second (m. 117) begins on a first inversion; and only the third (m. 125) states an unequivocal root position.

The opening ritornello is now represented only by the four measures of A, but the Devise, with its following tutti, is recapitulated complete. The 12-measure group thus formed (AAC as opposed to the original ABCAC) is a nice rhythmic link: its triple division and its pattern of repetition suggest the 2:1 ratio familiar from the development, but its final eight measures are closely united in a period familiar from the exposition. This suggests that the next period in its turn will refer to m. 25-40. These sixteen measures, however, are now doubled (m. 125-56), and only in the final ritornello do we find an exact correspondence, this time, of course, to m. 41-48. The parallel thus created is more consistent here than in the original version, with its repetition of the entire introduction. The final version, by virtue of the contrast of proportions—8:32:8 (1:4:1) in the recapitulation to 8:16:8 (1:2:1) in the exposition—points up more acutely the expansion of m. 125-56 than the original layout of 8:32:16 (1:4:2).

The doubling of measures 25-40 into the corresponding thirty-two measures of the recapitulation is achieved in the following way: first the four measures of phrase A, followed by an expanded B of ten, or 2 × 3 + 4. This is elided with a new group of four leading again to two groups of three, so clearly parallel with the preceding as to suggest that the original omission of the present m. 147 was an oversight; this time follow two measures of half-cadence. Finally we arrive at phrase C, now expanded to seven measures by the deceptive cadence and consequent elision. What we have, then, is a literal A followed by an expanded B; this is joined by an elision to what may be considered a varied repetition of the whole. And when we arrive at phrase C we find that it too is joined by an elision to its own repetition. So we come out roughly with ABABCC, or 1:2:1:2:1:1. The flute, again independent and simpler, breaks down into: 4 + 10, two measures' rest, 9 + 4—an almost symmetrical pattern, and one that leaves the voice free to perform its final flourish alone.

These calculations are summarized in Fig. 4, and I believe they do justify the cautious statement that the proportions of the ritornello have some influence on the rhythmic development of the aria as a whole.

Figure 4.

The influence is limited, however. It is tempting to point out that the introductory ritornello is just half as long as the rest of the exposition, which in turn is half as long as the development; but the attempt to carry this pattern or its reversal into the recapitulation fails.

One word might be added about the text. The extension in m. 103-12 that has stimulated so much of the foregoing discussion might be considered as an illustration of the words "höre nicht auf." It might also be thought an even more vivid illustration of the later words, "höret nicht auf bis dass du mich lehrest," with the "sehnlicher Lauf " constantly pushing on until at last taught "geduldig zu leiden." However, this may be, whether or not the passage was textually motivated, and whether or not in its turn it suggested the revised words, the essential point is that it is musically justified.