What sorts of analysis can assist performers of Mozart's music? My answer . . . just about everything.1

This paper offers various analytical perspectives that bear on performance issues in Mozart as I have applied them when teaching and coaching violin-sonata classes at Mannes College. In these courses, three or four student duos simultaneously prepared different sonatas by a single composer. This pedagogical organization allows the teacher/coach to address issues that usually do not arise during typical one-group/one-teacher chamber-music coaching.

First, because the class immerses itself in the performance issues of several works by a single composer, students can compare the composer's approaches to similar issues in different works. Second, having several duos in the class allows me to explain an issue only once instead of for each group separately. That efficiency allows time for consideration of larger stylistic issues, such as comparing the sonatas to the given composer's works in other genres. As a result, this pedagogical setting allows the sorts of comparisons that are only rarely a part of performance pedagogy, but are common in theoretical and historical courses. For example, I think of the brilliant insights that illuminate Charles Rosen's The Classical Style, especially when he draws upon Mozart's practices in one genre to make points about his works in a different genre.

My purpose in this paper is two-fold. First, I hope to show how knowledge of many analytical points (harmony, counterpoint, phrasing, form, motivic structures, instrumentation, and so forth) bears on performance issues. Second, I suggest how performance issues might be incorporated into courses on these topics.

Before I begin the analyses, a point about the musical examples is pertinent. When I teach courses to performers, I try to illustrate points whenever possible by pointing to features in the score, not by writing out analytic diagrams such as reductive voice-leading graphs, blocked-out chords, underlying species counterpoint, and the like. It is important that performers get in the habit of perceiving structures in the musical scores they play. All too often, I have found that performers, students as well as professionals, regard analytical diagrams as something other than "the music itself." I have no disagreement with using analytic examples to complement the score when those examples demonstrate something that's not obvious in the score itself. But when I work with performers on performance issues, I try to reduce to a minimum the use of any notated symbolism between them and the music. Therefore, when I read this paper, the examples were taken from Mozart's scores, with a few hand-written annotations on the scores. Because presenting full scores is impractical in a published paper, some of the examples here are more analytic than what I would use if I were talking directly to performers. Where possible, I have used abbreviated scores, including the sorts of things to which I would draw attention within a full score.

When a violin-sonata class turns to Mozart, the first work studied is often the opening movement of the E-minor Violin Sonata, K. 304. For players at any level, this movement is a good introduction to performance issues in Mozart: it is full of attractive and passionate music; it contains no technically difficult passages; there are few balance issues, since the violin and piano generally have clearly defined textural roles; and it is a compact movement built from a small number of themes.

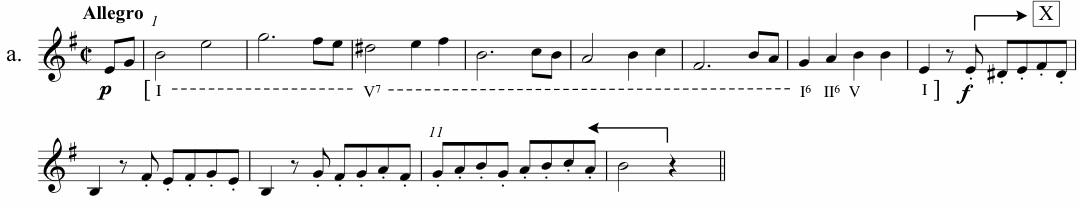

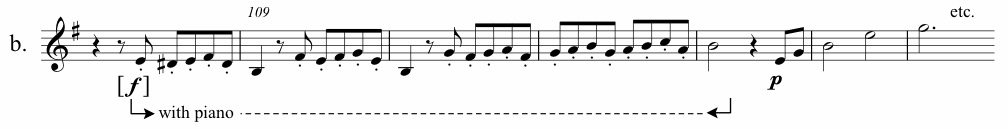

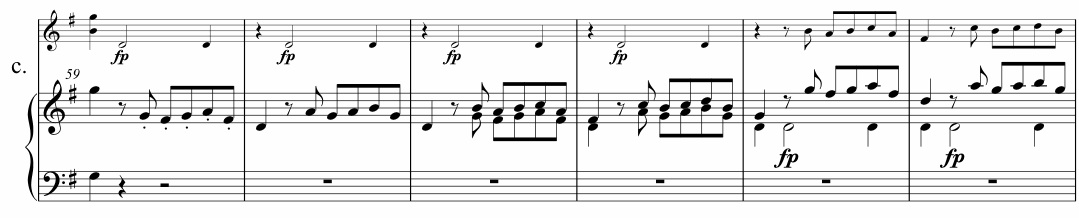

By that last point, I mean that the same thematic material serves multiple formal and rhetorical purposes at different points in the movement. For instance, the music in mm. 9-12 (labeled "X" in Example 1a) at first separates two statements of the complete opening phrase. The phrase returns literally in mm. 108-112 to serve as the retransition to the recapitulation (see Example 1b). And X-related material appears after the first period in the second key area (mm. 59-66, partly shown in Example 1c, and the corresponding location in the recapitulation). Likewise, a two-measure motive that begins the transition in m. 28 (not shown here) also begins the first melody in the second key area (mm. 37 ff.), and recurs to bring the second key area to its concluding cadence in mm. 67-73.

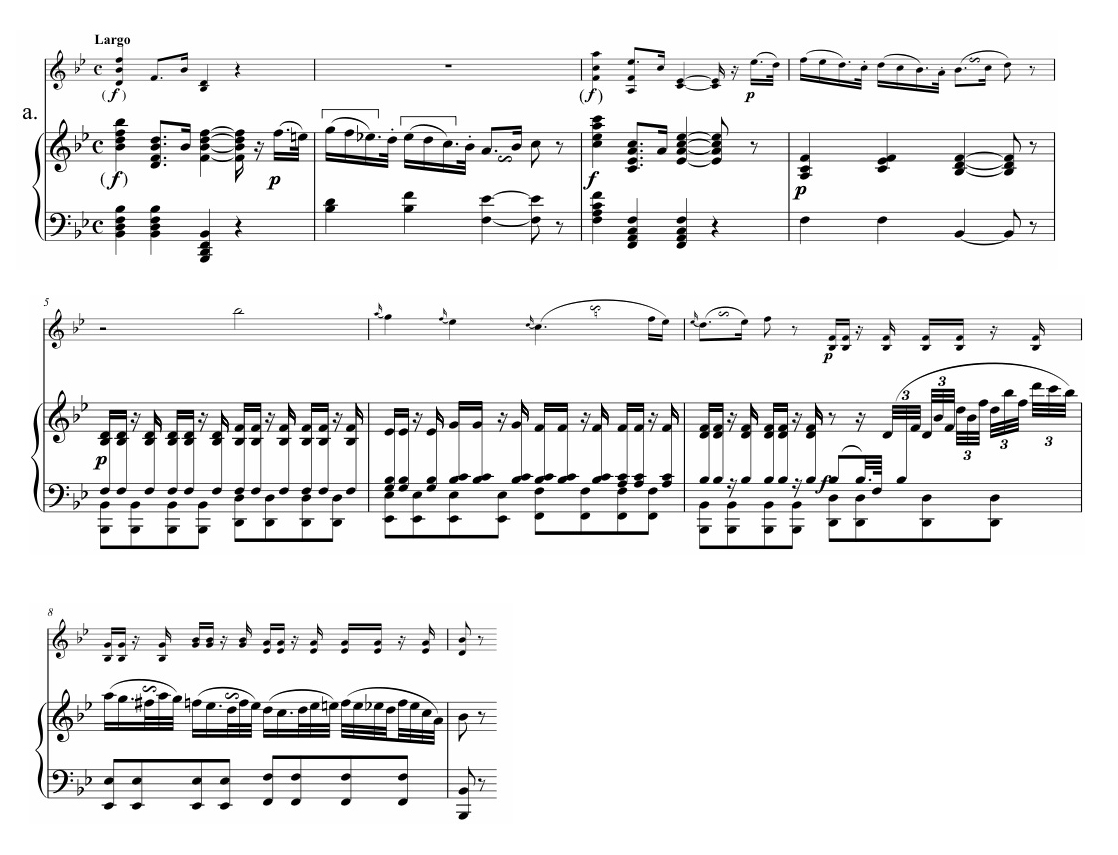

Example 1a. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 1-12, violin part. Both hands of the piano part double this melody at the unison or in octaves.

Example 1b. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 108-114, violin part. Mm. 108-112 feature the same doubling in the piano part as in mm. 9-12.

Example 1c. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 59-64

Indeed, the complete opening eight-measure phrase recurs quite often—more than commonly happens in Classical-era sonata-form movements. The melody appears in its entirety with identical notes and rhythms in the same key and in the same register in the violin part with the same bowings no fewer than four times during the course of the movement (seven times, if you count repeats). See Examples 1a, d, e, and g, that presents all four statements. And it is not only the entire phrase that is repeated. The eight-measure phrase is itself rhythmically repetitious—each two-measure unit of the melody begins with a two-eighth-note upbeat and ends with a long note on a downbeat. Seemingly adding to potential monotony, the bare octaves in the opening statement (mm. 1-8) preclude any textural relief. Alas, because of its structure, a dispiriting, sing-song performance is common here.

What might performers do, while playing the same phrase over and over and over and over and over and over and over (that's seven times), to keep it interesting?

One might listen first to the harmonies. Plausible harmonies appear below mm. 1-8 in Example 1a. The chord numbers are in brackets, since with only octaves one might hear other harmonies. Performers will swiftly discover that the theme's motives change along with these suggested chords. The tonic in mm. 1-2 lasts throughout the "Mannheim-rocket," confirming that those two measures probably should be projected as a single unit. The prolonged dominant in mm. 3-6 coincides with a new melodic motive and its sequence. With this harmonic parsing in mind, perhaps instead of playing the eight measures as 4+4 or 2+2+2+2 (which at first might have seemed obvious), the performers should connect the middle four measures of the phrase and play 2+4+2. They can do this by avoiding a half-cadential breath after m. 4, and instead begin m. 5 as a continuation of mm. 3-4 without a new initiating articulation. Note how the two concluding measures form a conventional cadence (scale-steps 3-4-5-1)—a new melodic element. Of course, this is a conventional bass line, not melody—something that has important consequences for the structure of the movement overall, as I discuss below.

After the X motive in mm. 9-12, also in octaves, Mozart introduces the movement's first homophonic texture by harmonizing a recurrence of the opening melody in mm. 13-20 (Example 1d), confirming the hypothetical harmonic parsing shown below Example 1a. Both the harmonic changes (two measures of tonic, four measures of root-position dominant, and two measures of cadence) and the contour of the piano part's right hand confirm the phrase parsing of 2+4+2. That is, as indicated by descending and rising arrows added to the score, the right-hand contour pattern during two measures of tonic (a descending line, then an ascending line) is broadened to cover four measures during the dominant (descending-descending-descending-ascending). In each case, the ascending motion marks the end of the harmony. If the pianist applies to the right hand in mm. 13-18 the common mannerism of a slight diminuendo during a descending line and a slight crescendo during an ascending line, the changes of harmony will be marked and the harmonies will be connected to one another (via the mini-crescendo leading from one harmony to the next).

Example 1d. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 13-20

Another aspect of the harmonization in mm. 13-20 suggests options for differentiating the violinist's bow-strokes. During the prolonged harmonies in the first six measures of the phrase, the violinist might play the quarter notes relatively legato, finding a style that matches the legato notated by Mozart in the accompaniment. But the quarter-note harmonic rhythm in m. 19 suggests using a more marcato stroke for the quarter notes here (and perhaps also in m. 7).

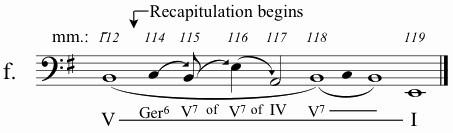

The thematic return at the beginning of the recapitulation in mm. 113-120 (Example 1e) features radically different harmonies. On the one hand, with the first measure unaccompanied (the only solo-violin measure in the entire movement!), and with an augmented-sixth chord in the second measure, there is little sense of a strong tonic arrival. On the other hand, since we have already heard the retransition music (as the X passage) preparing for the theme in mm. 9-12 (and heard it twice, if the repeat was taken), we have a strong expectation that the theme will begin with a firm tonic (even if the piano is silent in that first measure). On the third hand, using the X passage from mm. 9-12 as the retransition means that there is a literal statement of material from the exposition prior to the first theme. That might momentarily make us wonder if we had somehow missed an earlier arrival on the recapitulation. All this suggests that the violinist should do something special during that first unaccompanied measure of the recapitulation and that the pianist respond appropriately. For instance, one could pretend that m. 113 is not a major arrival—by not taking a big breath before the theme, and perhaps by projecting the opening measure of the theme as an upbeat to the second measure. Or one could go in the opposite direction and pretend that it is indeed a double return—take a big breath before the return, play the first measure as a hypermetrically strong measure, and let the piano shockingly break the mood. It does not matter exactly what one does, so long as one does something to take note of the surprises. The only uninteresting performance here would be for the violinist to ignore the surprises and play the theme as it began the movement.

Example 1e. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 113-120

During the theme in mm. 113-120, the unexpected chromatic harmonies, the forte-pianos every other measure, and the delay of the arrival on a strong dominant until the sixth (!) measure of the phrase should surely inspire performers to parse the phrase differently than they did in the exposition. Furthermore, with the augmented-sixth as the first harmony in the recapitulation, and with the circle-of-fifths harmonization ending on the subdominant in m. 117 that returns to the dominant in the next measure, the first five measures of the recapitulation constitute a neighboring motion from the dominant that ended the retransition (Example 1f). This might suggest underplaying the usual sense of arrival that we commonly associate with thematic returns at the beginning of recapitulations. The violinist might even consider avoiding playing the pairs of measures in the theme as strong-weak (which was implicit in both statements of the theme in the exposition because of the harmonic rhythm). The violinist could shape each of the two-measure units so that they begin with an upbeat lasting five quarter-notes, expressing the forte-pianos as arrivals on a hypermetric downbeat, not as syncopations at that metric level. Of course, the violinist could also insist on beginning the two-measure groups as before, thus making those forte-pianos syncopations. Once again, it is not so much a matter of making one specific decision as it is of reacting in some appropriate way to the musical structure. All sorts of timbral nuances by the violinist (bow speed and vibrato, for instance) should inspire the pianist to consider various ways of shaping the forte-pianos and the repeated eighth-notes.

Example 1f. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 112-120, the underlying harmonies

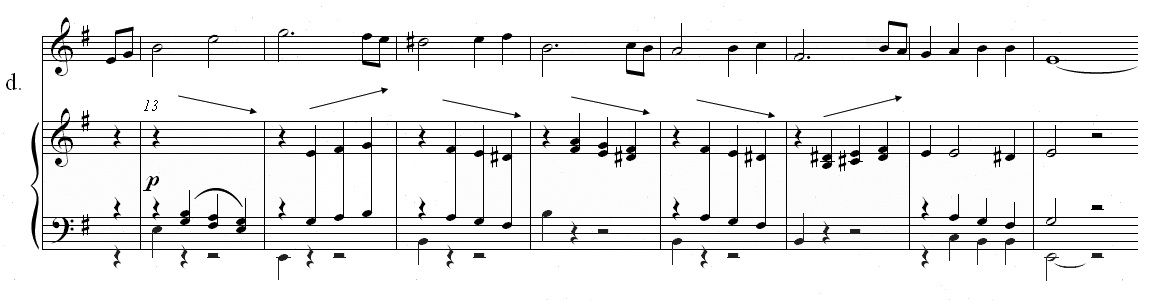

The final re-harmonization of the theme at the beginning of the coda in mm. 193-200 (Example 1g) is the most normal of all—a harmonization appropriate to bringing the movement to its end. By "normal," I mean not only the presence of an accompaniment pattern over a bass line. In addition, this is the first harmonization that unambiguously articulates a 4+4 grouping of the eight measures. To ensure that the phrase is parsed as 4+4, Mozart changes harmony in the fifth measure—ingeniously placing a C in the bass (the same bass note as at the beginning of the recapitulation) to separate the dividing or semi-cadential dominant that ends the first four measures of the theme from what now clearly is a more local dominant that begins the second half of the phrase.

Example 1g. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: mm. 193-200

These four different harmonizations of the theme create a musical narrative over the course of the movement. The first appearance, in which so much is unstated due to the bare octaves, could range in character from being mysterious or ambiguous (despite the textural clarity) to being assertive (despite the soft dynamic). Whatever is clarified by the theme's second appearance is surely unsettled by the operatic recitativo-accompagnato texture and the rhythmic and harmonic surprises at the beginning of the recapitulation. And the texture in the coda could express a return to the snug comfort of normality after the oddities of the previous statements, or a fatalistic resignation after having struggled to avoid just such normality. I do not care terribly much about which narrative is told. But I am concerned that the performers relate a musical narrative, which, in my view, is frequently the essence of Mozart's music.

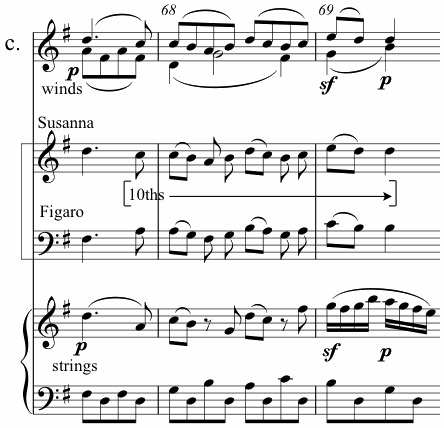

Once performers realize that a Mozart sonata can project a musical narrative, they can turn to his operas to study how he created musical narratives to complement the drama. The very opening number of Le Nozze di Figaro is exemplary. It is short; the dramatic situation is easily grasped; and the narrative techniques are clear. As the curtain rises on the first act, we meet Susanna and Figaro—a betrothed couple clearly fond of each other, yet nervously self-absorbed. Figaro measures the room, while Susanna admires her bonnet.2 Even before they sing, Mozart portrays their lack of communication via two quite different, effervescent tunes (A and B in Example 2a). Each theme has its own orchestration—mostly strings for A, mostly winds for B. When they begin to sing, Figaro measures to the A theme, Susanna preens to the B theme.

Example 2ab. Mozart, Le Nozze di Figaro, Act 1, scene 1, mm. 1-11: a is abbreviated score, b is the underlying structure.

Mozart faced a compositional problem here. How should he portray the protagonists ignoring each other, while underneath it all making it clear that both are expressing a range of jitters about the same thing: their imminent wedding? After all, by the end of the duet, Susanna and Figaro will joyously sing the B theme in rhythmic unison largely in parallel tenths (m. 67 ff.). Mozart's solution (of course!) is ingenious, utilizing (1) the underlying harmonic structure, (2) motives, (3) counterpoint, and (4) orchestration.

Scale-step numbers above the analytical score in Example 2b show that the high notes in the A theme ascend conjunctly from an implied scale-step 1 up to 5 in mm. 1-7. The B theme, beginning in m. 10, repeats the conjunct ascent from scale-steps 3 to 5 three times in mm. 10-11, 12-13, and 14-15. Furthermore, the same bass motion supports the melodic motion through scale-steps 3-4-5 in both melodies: scale-steps 1-2-3 moving in parallel tenths below the melody. As a result, the two themes—despite all their obvious differences—have the identical underlying structure. A motivic evolution enhances this relationship between the two themes: the bass countersubject to the A theme provides the main melodic figure of the B theme, since the decorated resolution of the bass suspensions is the turn figure that characterizes the B theme. Indeed, the B theme begins with the very same pitches as the last appearance of that bass counterpoint, C-B-A-B (bracketed in the bass line in m. 7 and in the melody in m. 10 in Example 2a). And there is even an orchestrational connection. Mozart has the bassoon in mm. 1-7 double the cellos, basses, and violas; this provides a timbral link between the largely string sound of the beginning of the A theme and the woodwind ensemble of the B theme. As a result, just as in the dramatic narrative, the musical narrative begins with two characters (expressed as two themes) that differ in obvious ways, but that share motives (both in the sense of surface motives and the underlying structure).

As Susanna and Figaro gradually come to communicate with each other, Mozart creates a musical communication between the two themes by relating them more and more closely. When the singers first enter, they sing the two themes in sequence pretty much as they appear in the instrumental introduction, retaining and even reinforcing the original orchestrations. Thus, as Figaro measures to the A theme in mm. 19-30 (not shown here), the timbre of strings and bassoon is not supplemented by other winds (as did occur during the A theme's crescendo in mm. 6-9). Likewise, Susanna sings the B theme in mm. 30-36 largely accompanied by the winds. But beginning in m. 36, when Susanna more insistently seeks Figaro's attention, Mozart at first not only combines the two singers, but he also combines the two timbral groups, adding more wind color to the extension of the A theme. When Figaro finally heeds Susanna and stops counting, he sings the B theme (previously Susanna's tune) in m. 49 against a reversal of its prior orchestration—the strings (not the winds) now play the melody. (Is Mozart's point in having Figaro sing Susanna's theme with Figaro's orchestration—strings—that Figaro is really still thinking about counting, and is only pretending to pay attention to Susanna?) By m. 67, Figaro has forgotten about counting and the two singers join in parallel tenths on the B theme to enthuse about their coming wedding (Example 2c). To indicate that the two characters are now synchronized with one another, Mozart now has the violins join the winds in the B theme—combining Figaro's and Susanna's orchestrations. But the doubling is not literal; the violins double only some notes, not all. Susanna and Figaro, after all, are still two different people. They may sing together, but they are not yet married. Mozart even draws the opening bass countersubject into the culmination of the duet, as the second oboe and second bassoon in m. 68 (and in the repetitions in mm. 70 and 72) play the syncopated suspensions that hitherto appeared exclusively against the A theme.

Example 2c. Mozart, Le Nozze di Figaro, Act 1, scene 1: c. mm. 67-69

I have been avoiding a particular word that is, in my mind, the key to a successful performance of Mozart's music: characterization. Opera coaches regularly point to the libretto as a key to characterization. But words do not exist by themselves in Figaro. All aspects of structure, including harmony, counterpoint, motives at every level, texture, and timbre create the musical setting of the libretto—its characterization. Knowing how these musical elements create characterization in Mozart's dramatic works helps us to understand how they create characterizations in his instrumental music.

What might be applied from this perspective on Figaro to a performance of the E-minor Violin Sonata? Consider orchestration—or, in the violin sonata, timbre. If the setting changes, so does the characterization. As the four statements of the opening theme appear throughout the movement, they should differ expressively. The pianist might imagine Mozartean orchestrations of their accompaniments. For instance, should the opening of the coda ( Example 1g) be imagined with strings alone, imparting a warm blend? In this case, slight finger-pedaling could help create the right sonority. Or, perhaps, should it be imagined with sustained wind colors joining the strings, uniting various colors from earlier in the movement—just as Mozart combines colors at the end of the duet in Figaro? For that effect, perhaps the sustaining pedal might help. How might the violinist join the piano in the various statements of the theme—blended, or as a soloist against an orchestra? There are multiple options, whether one uses modern or period techniques on either instrument.

Furthermore, knowing about the underlying structural similarities of the two themes in Figaro might inspire the violinist and pianist to seek such relationships in the sonata. Exploration might begin with an already noted anomaly in the opening phrase. Whereas the first six measures of the phrase present motions characteristic of melodies (arpeggiations, passing tones, and a melodic sequence), the concluding pair of measures—scale-steps 3-4-5-1—form a characteristic cadential bass line. Because that motion is in the melody, no full accompaniment to this theme can ever feature that motion in the bass. And melodically, since the theme ends 5-1, there can never be a cadence to this theme with a strong conclusive melodic motion such as scale steps 2-1 or 7-8. Does that 3-4-5-1 motion ever appear as a bass line?

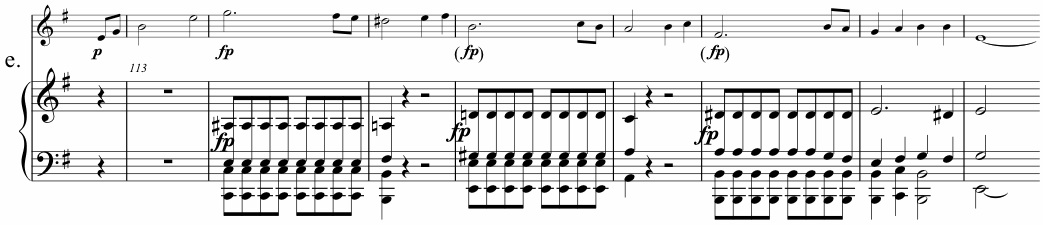

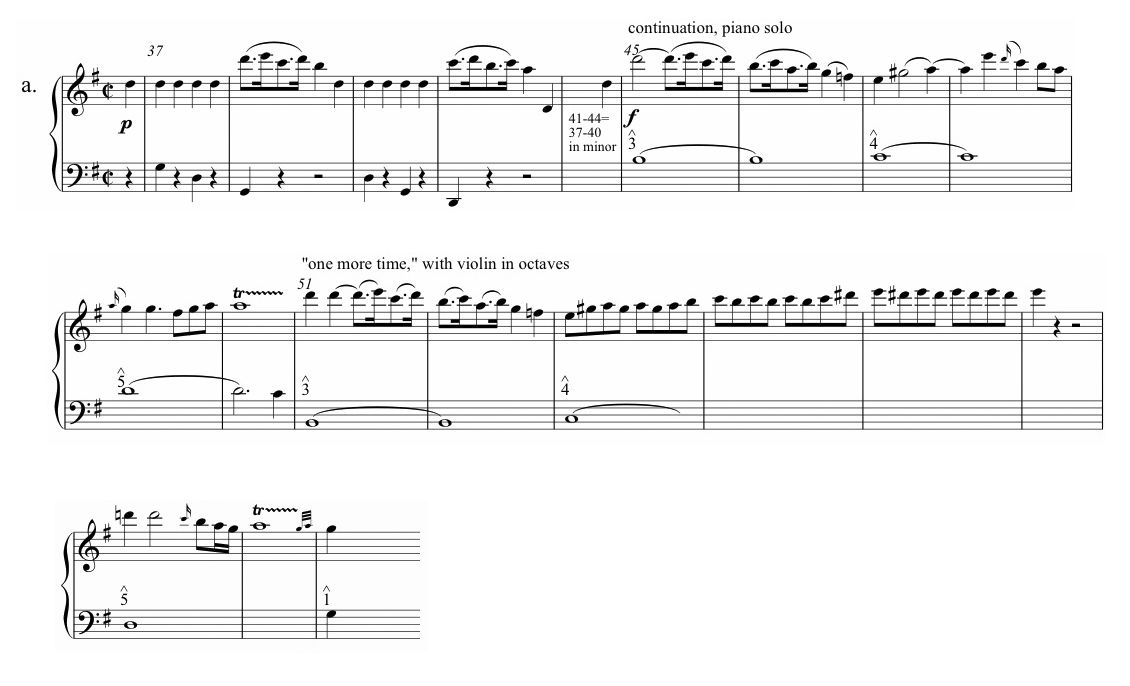

Yes it does, beginning in m. 45. William Caplin has pointed out that an expansion of this cadential bass supporting I6-IV(or ii6)-V-I is common in the Classical era to create large-scale strong cadences.3 In the first movement of the E-minor Sonata, the motion is especially prominent when it occurs as the bass support for an extended phrase leading to a cadence in the second key area. Example 3a outlines the theme that begins the second key area. From mm. 45 to 59, the bass outlines scale-steps 3-4-5, 3-4-5-1. And Mozart calls attention to this section of the movement by using 3-4-5 in the bass to support the very first piano solo in the movement during which the violin is silent (mm. 45-50). And that piano solo is also the first extended forte melody in the movement as well as the first to remain in the very highest register of the keyboard. (Remember that the highest note on Mozart's piano was F.) Lastly, this motion toward a cadence is subjected to the "one-more-time" cadential reinforcement technique so aptly named by Janet Schmalfeldt.4 Note that during this "one-more-time" second statement in mm. 51-53, the violin and piano play in octaves, connecting the cadence in the second key area to the texture of the opening phrase of the movement. (This is analogous to the role of the parallel tenths in both of the themes of the duet from Figaro in the sense that an interval that played an important role at the beginning of the movement recurs later at a culminating moment bringing together disparate elements from the opening.)

Example 3a. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: the first theme of the second key area, mm. 37-59, short score

When the music in mm. 45-59 recurs in the recapitulation, it is in the tonic key. As a result, scale-steps 3-4-5-1 in the bass are G-A-B-E—the last notes of the opening phrase of the movement. Finally, going into m. 159, a cadence appears in which the thematic 3-4-5-1 (in the bass) supports scale-steps 7-8 and 2-1 in the tonic key. The drama of this moment is heightened by the concerto-like extended double trill at the cadence in both the piano and violin, which does not occur in the exposition, as shown in Example 3b.

Example 3b. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in E minor, K. 304, first movement: b. the end of the same theme in the recapitulation, mm. 157-159

I suggested earlier that the violinist and pianist could articulate the quarter notes in mm. 7-8 (Example 1a) to underscore that the quarter notes G-A-B represent separate harmonies in the implied formulaic cadence—different in kind from the quarter notes earlier in the melody that were passing tones within a harmony. Knowing that 3-4-5-1 as a bass line underlies a long stretch of music in the second key area encourages the performers to maintain an unbroken sweep throughout mm. 45-50 and its "one-more-time" intensification in mm. 51-59. Mozart supports this interpretation in a number of ways, not least by maintaining rhythmic continuity even during the extension of the pre-dominant chord in mm. 53-56 (Example 3a). A beautifully effective way of keeping the music moving forward is making sure to bring out the forte bass re-entry in m. 56 as the upper parts fade away.

Even harmonic theory makes it clear right from m. 45 that the phrase and its one-more-time repetition are a single large unit quite different from the preceding shorter units. The four-measure phrase that begins the second theme group (mm. 37-40) features only root-position tonic and dominant harmonies. By contrast, after the repetition of that phrase in the minor mode, m. 45 begins with a first-inversion tonic triad. Two common uses of a first-inversion tonic chord are (1) to prolong the tonic by voice exchanges, motion in parallel tenths, and so forth, and (2) to neighbor to a pre-dominant chord that has scale-step 4 in the bass. Often in Classical-era music, this latter use of a first-inversion tonic occurs at the end of a tonic prolongation, and signals that the phrase is no longer prolonging the opening tonic, but that motion has begun toward the dominant. When that occurs here in m. 45, the change of inversion launches a longer unit that will lead to the cadence.

For performers to launch that longer unit, they must give the gesture the sense—right from its beginning—that its conclusion is a longer ways off than has been the case with some of the preceding gestures. I often cite an exceedingly well-known snippet of Shakespeare to reinforce this point to performers. The line "To be, or not to be" contains three iambic feet. But the three feet are not equivalent. The first foot ("To be") is a separate unit, whereas the second foot ("or not") makes no sense except as the initiation of a two-foot gesture. Of all the possible effective enunciations of that line, every one of them must make it clear right from the word "or" that the unit about to unfold will be longer than the preceding one. The same principle is at work in all sentence phrasing structures (2+2+4 or longer sections in the same proportion): the longer concluding unit (the continuation phrase) requires a different sort of initiation than the shorter preceding units. Mozart here makes that clear by means of harmony, register, dynamics, and change of instrumentation—the first-inversion tonic is a more mobile chord than a root-position tonic; the higher register and louder dynamics carry more energy; and the pianist becomes an unaccompanied soloist for the first time in the movement.

The pianist might launch the longer phrase effectively in a number of ways: by inserting a breath before the upbeat to m. 45, by slightly lengthening the upbeat to m. 45, by starting m. 45 with a slight tenuto, by emphasizing the change from staccato to legato in the accompaniment, by clearly asserting the new dynamic, by changing the inner pulse from one-measure metric units to two-measure hyper-metric units, by slightly adjusting the tempo—or by a combination of some or all of these factors and others of similar ilk. But the moment should not pass without special attention. Lastly, the effect in the recapitulation should be even more expansive and more conclusive, since that phrase will end in that double trill in mm. 158-159.

Personally, I enjoy Mozart performances that clearly articulate different lengths and characters at a wide range of structural levels from motives to phrases to sections of movements. But whatever performance style one adopts, the structural matters that I have been discussing lie at the heart of his music.

My last example is the first movement of a violin sonata on a much grander scale—the Sonata in B-flat Major, K. 454. Where the first movement of the E-minor Sonata is a compact movement with a limited amount of thematic material and clearly defined roles for the violin and piano at almost all points, the first movement of the B-flat Sonata is on a symphonic scale with a slow introduction, a plethora of themes, and considerable textural complexity.

All this is apparent at the beginning of the introduction (Example 4a). Measures 1 and 3 feature a quasi-orchestral tutti texture. Here Mozart imitates a common Classical-era orchestration technique for massive sonorities by not making it clear whether the top of the piano chords or the top of the violin chords is the leading line. This is similar to tutti orchestrations in which the first violins may have the leading motive, but some woodwinds play higher notes with other material. By contrast, mm. 2 and 4 feature a concerto-like solo texture with accompaniment. The four measures form a 2+2 antecedent-consequent phrase-pair. A totally new texture and melody begin a longer phrase in m. 5; a varied repetition of that phrase starts in m. 7 and arrives at a conclusive cadence on the downbeat of m. 9. At least three distinct thematic elements have been presented by that point: the tutti, the concerto-like solo plus accompaniment in mm. 2 and 4, and the accompaniment and aria-like music in mm. 5-9.

Example 4a. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement: the beginning of the introduction, mm. 1-9

Analogous things happen in the 2+2+4 sentence that begins the Allegro (Example 4b). The first six measures contain three sets of motives that differ in melodic contour, voicing, and texture: one set of motives each for the antecedent and consequent (each two measures long as at the opening of the Largo), and new motives for the ensuing four-measure continuation phrase that leads to a half-cadence. With respect to textural complexity, in the four-measure continuation phrase beginning in m. 18, the violin seems to take the lead in the second measure by imitating the piano in a higher register, but then the piano emerges during that measure as once again having the leading part shortly before the violin drops out entirely.

Example 4b. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement: the beginning of the allegro, mm. 14-22

The performance implications that I applied to the more obviously structured sentence that begins the second key area of the E-minor Sonata help us understand how the materials and textures in both the Largo and the Allegro of K. 454 relate to one another. Consider the harmony at the beginning of the Largo, for instance. As at the opening of the second key area of the E-minor Sonata (Example 3a), the antecedent and consequent phrases that begin the Largo contain only root-position tonic and dominant chords. These harmonies form a single tonic-dominant-tonic progression over mm. 1-4, fostering the sense that these four measures add up to a single larger unit, and are not just a collection of four measures, or only a pair of solos preceded by tuttis. They form a unity despite the changes in texture in each consecutive measure. A harmonic detail in m. 2 (something surely taught in all harmony classes) reinforces the sense of a four-measure unit: the dominant in m. 2 has a seventh throughout its duration. Hence, the end of m. 2 is less of a half cadence (which in the Classical-era generally features a simple dominant triad) than a pause within a more continuous progression. The violinist and pianist should project the continuity of the opening four-measure unit by how they pace the connections between the measures. The longer phrase beginning in m. 5 and its repeat, as in the second key area of the E minor sonata, uses a more extensive harmonic vocabulary—the very same I6-ii6-V progression that supported the continuation one-more-time phrase in the second key area of the E-minor Sonata. Here, too, performers need to launch the new gesture in m. 5 as a single motion to a long-range goal.

Studying how motives interact with harmony at the opening of the Largo suggests further performance nuances. Consider the filled-in melodic thirds in m. 2 (bracketed in Example 4a). Here as in most music, recognizing motives will not be all that helpful to making good performance decisions unless one also understands how the motives interact with the harmonic structure. The first two thirds do not outline a harmonic interval. Rather, the G and Eb on beats 1 and 2 are an appoggiatura and an accented passing tone leaning on F and D, respectively. A left-hand detail confirms this: D moving to F in the tenor creates a voice exchange with the melody's chord tones, as shown in Example 4c. And Mozart's rather fussy articulations reinforce the point; from the upbeat going into beat 1, he breaks the double neighbor into two slurs, and, surprisingly, continues the slur through the Eb. He clearly did not want a stable tonic just sitting there, as would have been the case if he had written the less dynamic version that appears in Example 4d, where the thirds on beats 1 and 2 outline chord tones. With this knowledge, the pianist might decide to put some weight on the G and Eb on beats 1 and 2, avoid being too restful on the third note of the slurs, and ensure that the voice-exchange is audible (probably by voicing the tenor to ensure that it can be heard). The third that does fill in a harmonic interval is A-C on beats 3-4. Here, the pianist can relish the outlined harmonic interval—but not too much, since the underlying dominant-seventh is dissonant.

Example 4c. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement: a voice-leading detail in m. 2

Example 4d. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement: an inferior version of m. 2

Most of the issues facing the violinist in m. 4 are comparable. One additional point concerns the F on the downbeat of that measure. Even though that F forms an octave against the bass, it is not a stable tone, but rather, a part of a double neighbor around the chord-seventh Eb and therefore should lean on the Eb.

A few insights into texture can help the player grasp the continuity within the first four measures. The left-hand chords in m. 1 change register on the third beat—something that might pass with little attention, but for the fact that moving to a lower register on the third beat foreshadows the harmonic motion involving a similar repeated-note-followed-by-a-descending-skip in m. 2. It is helpful to practice the left hand alone during mm. 1-2 to get the feel of that slow-motion parallelism. When that left-hand contour pattern changes in m. 3, a bit of attention by the pianist to the syncopated change of register can animate the dominant-seventh chord more than the tonic chord in the analogous position in the first measure.

Another set of details concerns the antecedent and consequent period at the beginning of the Allegro. The Allegro opens with the melodic motive D-Eb-F, a pitch-specific motive that saturates the texture here, as shown by the brackets in Example 4b. Despite the totally different compositional surface in mm. 16-17, the same D-Eb-F also underlies those measures, as shown in Example 4e. Hence, mm. 16-17 are a reworking of mm. 14-15, not solely a new idea or a rhetorical aside. But, at the same time, because mm. 16-17 are so different from mm. 14-15 in texture, register, motive, affect, and gesture, mm. 16-17 are not in fact merely the second leg of a sentence. Mm. 16-17 are not a repetition of mm. 14-15. Our phrasing theories are insufficiently refined to deal with a musical surface that is a repeat in terms of underlying counterpoint but a contrasting idea at the foreground.

Example 4e. Mozart, Sonata for Violin and Piano in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement: the underlying structure of mm. 16-17

But phrasing theory aside, it is wonderful if performers can balance aspects of both notions—that there is a new idea, but that they are both built of the same substratum (as with the A and B themes in the duet from Figaro). Doing so would entail characterizing each idea distinctly while keeping some underlying similarity. For instance, instead of doing the obvious and playing mm. 16-17 weak-strong (obvious because of the dissonance on the downbeat of m. 17, the quasi-agogic accent there caused by the change in the quality of motion, and the airiness of the motion leading to the downbeat of m. 17), one might project mm. 16-17 as strong-weak (perhaps via the common mannerism of a slight crescendo-diminuendo to and from the high note on the downbeat of m. 16 and even a slight tenuto on that downbeat). In the immediately following music, Mozart seems to be playing with these hypermetric options. The piano part, thanks to the left hand forte re-entry in m. 17 (which reverses the D-Eb-F motive into F-Eb-D) and the specifically notated arpeggiation of the right hand on the downbeat of m. 17, restores the hypermetric emphasis back on the first measure of the next pair of measures. But the violin, with its imitation in the next measure, contests that hypermetric structure.

At the 2006 annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, the Music Theory Pedagogy Interest Group sponsored a session on "Performance and Analysis" in the form of a series of coachings. In the ensuing discussion, Ed Klorman, a fine violist and theorist, noted that just about all of the suggestions for performance he heard during the session were akin to the instructions he had heard from non-theorist performers in the course of coachings. I am confident that most of my specific performance suggestions fall into the same category.

What, then, is the advantage of applying analysis to performance? I think the difference is not in the specific remarks themselves—at least in most cases. Rather, it is the pedagogical value—ultimately the autodidactic value—of the approach. I remember that when I was a violin student, in the course of a coaching I would learn to emphasize this or that note, add extra vibrato here or there, and so forth. To be sure, most such instructions enhanced the performance. I came to believe that a performer's education meant learning similar points about the vast repertoire. But I do not remember ever hearing a reason for suggested nuances. Perhaps the closest thing to a reason came during a coaching of Mozart's G-minor Piano Quartet by the eminent violist Lillian Fuchs, who noted that "chromaticism in Mozart means to play with more emotion."

Analysis creates a context for making performance decisions, allowing us more readily to apply what we have learned in one piece or one passage to other pieces and passages, and not just similar passages. Therefore, I think Ed Klorman raised a very good point by questioning whether analysis might generate any specific performance suggestions. If it is a matter of "breathe here" or "bring out that line," he is correct. What interests me is the method by which one arrives at the insights that generate those remarks. Ideally, our performance students will learn to listen for structural principles that can be applied to numerous situations, and, as they apply those principles, they will develop sensitivity to the infinite range of nuances that such structures suggest.

Where should this learning take place? I hope my answer has been implicit in my remarks: whenever we teach theory. For instance, when we teach the differences between cadential progressions and more elaborative progressions, any passage we use to illustrate these progressions can generate suggestions for effective performance. Play a recording (or a couple of recordings) of the passage in a theory class, listen to the differences between them, and discuss the effectiveness of the performances. Or perform the passage in multiple ways and discuss whether projecting the analytic insight affects the performance's effectiveness. I know that this takes class time. But what seem like digressions may well deepen students' appreciation of the value of analysis and inspire their further self-study.

The differences between top-notch student performances and readings by the greatest artists are rarely a matter of hitting the right notes. Rather, innumerable barely perceptible nuances are what often distinguish a great performance. But what a difference those nuances make! Some musicians seem to have a knack for making those nuances. In effect, they speak the language innately. For the rest of us mere mortals, all the knowledge we can apply can be of help.

Bibliography

Caplin, William. Classical form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Lewin, David. "Figaro's Mistakes." Current Musicology 57 (1995): 45‒60. Reprinted in Engaging Music: Essays In Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Rosen, Charles. The Classical Style. New York: Viking, 1970; New York: W. W. Norton, 1971.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. "Cadential Processes: The Evaded Cadence and the 'One More Time' Technique." The Journal of Musicological Research 12 (1992): 1‒52.

Notes

1An earlier version of this paper was read at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory in Los Angeles in 2007. Access to scores of the following Mozart works will assist the reader: Violin Sonata in E minor, K. 304, first movement; Violin Sonata in B-flat major, K. 454, first movement; Le Nozze di Figaro (full score), opening duet of Act I.

2David Lewin analyzed—or, perhaps better said, psychoanalyzed—Figaro's apparent counting mistakes in this duet in "Figaro's Mistakes." Lewin's analysis discusses different aspects of the score than the present study.