Ottorino Respighi (1879–1936) is best known for his “Roman Trilogy,” the orchestral pieces Fountains of Rome, Pines of Rome and Roman Festivals. His music for orchestra signaled the rebirth of Italian symphonic music and a restored appreciation of Renaissance as well as Baroque musical forms. Respighi embraced the continuity of tradition with a love of the ancient world, and thereby promoted a revival of older musical ideas within the context of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century elements. For this reason, Respighi’s music may be considered the culmination of the Italian symphonic tradition that originated with the music of Antonio Vivaldi. In 1916, at the age of 37, Respighi achieved international recognition with his tone poem Fountains of Rome. He had moved to the eternal city after being appointed composition teacher at the Conservatory of Santa Cecilia in 1913. While we are keenly aware of Respighi’s compositional output following Fountains, we know very little about his earlier works, especially the orchestral works which predate his pivotal work of 1916. Respighi was first noticed for his orchestration of the Lamento di Arianna from Claudio Monteverdi’s lost opera Arianna. In 1908, it was successfully premiered in Berlin under conductor Artur Nikisch. He then gained national attention with the Bologna premiere of his first opera Semirama in 1910. But it was Fountains that firmly established Respighi’s voice, as a leading composer of his time.

In this essay I would like to bring some of Respighi’s early works to light and reveal not only their integrity as significant musical accomplishments but also call attention to their derived influences and close connections to his later works. I will begin to lay down a foundation for such a comparative analysis by focusing on two particularly important early compositions: Aria for strings of 1901 and Suite for strings of 1902.1 My research on this subject evolved over several years of work in collaboration with Respighi’s family descendants, cataloguer and curators, musicologists and museum archives2 in several cities in Italy. In 2008 I was invited by Respighi's family descendents to begin editing a number of early works (including the completion of an unfinished violin concerto) for publication. The Aria, Suite for strings and the Violin Concerto in A Major (of 1903) are the first of several critical editions released with the Italian publisher Edizioni Panastudio.3 Other editions include Serenata per piccola orchestra (of 1904), Suite in Sol Maggiore (of 1905), Il Lamento di Arianna (of 1908), and Tre Liriche for mezzo soprano and orchestra (of 1913).

The years 1901 to 1903 were a poignant time in Respighi’s life and early career. Following his graduation from the Bologna music conservatory, Respighi travelled to St. Petersburg, Russia in 1900 to play viola for the Imperial Theatre Orchestra’s season of Italian opera. After five months, during which he studied with Rimsky-Korsakov, Respighi returned to Bologna to earn a second diploma in composition. During this period, Respighi’s principal activities involved his role as first violin in the Mugellini Quintet. His combined experiences as violist and violinist no doubt influenced his choices in composition, explaining his focus on the writing of string music. Over these three years, Respighi’s output includes several works either featuring string orchestra (e.g. Minuet) or chamber music involving strings (e.g. Quartet in D Flat Major), as well as certain works for small orchestra (e.g. Piano Concerto in A minor). At this time Respighi essentially developed a variety of compositions which incorporated Baroque forms and dances, often in combination with modern techniques, and featured solo string instruments in combination with chamber, strings ensemble or small and full orchestra. In addition to the above-mentioned works, these include Suite for piano, Prelude, Chorale and Fugue for orchestra, and Humoresque for violin and orchestra.

For the works discussed below, I will include the title and opus number (P.)–as per Respighi cataloguer Potito Pedarra,4 as well as durations, movement titles and tempi (with suggested metronome markings).

Title: Aria for strings5 P. 32,

Duration: c. 6 minutes

One Movement. Lento. (quarter = c. 56)

Respighi loved the Aria for strings (1901), for he included it in two multi-movement works: Suite in G Major for Organ and strings (of 1905) and the Suite for Flute and strings No. 2 (of 1906).

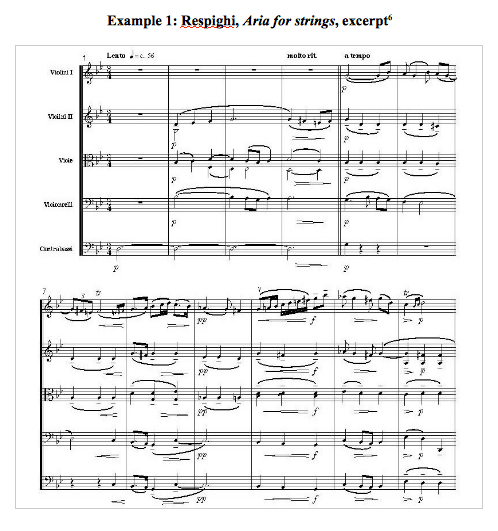

Example 1, Respighi, Aria for strings, excerpt. 6

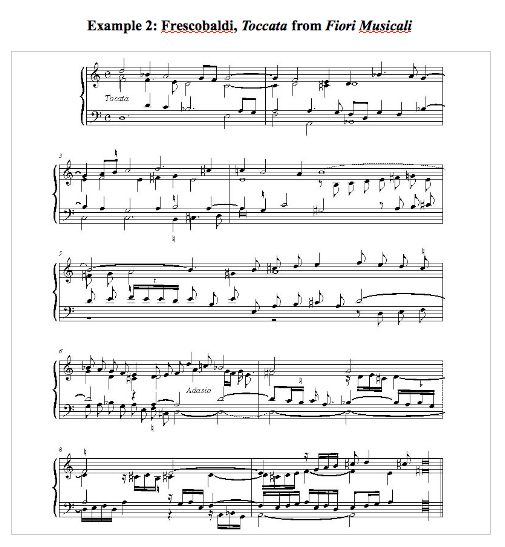

The chorale-like Aria in G minor clearly expresses Respighi's deep affection for early music and, most especially, the composers of the Italian Baroque, such as Arcangelo Corelli, Girolamo Frescobaldi, and Antonio Vivaldi. This expressive work, in the style of an “aria di chiesa,” is quite lyrical, yet simple and well-balanced in form. In addition, the music is remarkably poignant—if not dramatic—for such an early piece. It demonstrates Respighi’s natural ability for romantic gestures and evolving dynamics. The influences stemming principally from Frescobaldi become more apparent as the music unfolds. Frescobaldi’s madrigal-like melodies with simple textures in minor, together with a mix of chromaticism and use of embellished ornamentations inspired Respighi. The “Ricercare” in Frescobaldi’s Mass of the Virgin, for example, contains devices present in Respighi’s Aria. Frescobaldi used a typical monothematic theme with a chromatic subject, to which he added moments of augmentation and an ever-present pedal note passage near final cadences. All of these characteristics are also present in the toccatas in Frescobaldi’s highly influential work Fiori Musicali. Frescobaldi’s Toccata Avanti la Messa Della Domenica from Fiori Musicali is another wonderful testament to the various influences manifested in Respighi’s early music, as we can surely trace in the Aria for strings. This toccata brings together the variety of inspirations noted above, as well as Frescobaldi’s modal awareness and incessant nature for clarity of line, that is, the simple ascending or descending flow of melodies—at times, occurring in sixths. The latter is, no doubt, a fine example of Johann Joseph Fux’s methodology.

Example 2, Frescobaldi, Toccata from Fiori Musicali.

Respighi’s admiration of Frescobaldi’s music is manifest again in 1917, when he transcribed three Frescobaldi organ works for the pianoforte: Passacaglia, Prelude and Fugue in G minor, and Toccata and Fugue in A minor. Coupled with these transcriptions, we may safely assert that Frescobaldi’s music had a strong, irreversible impact on Ottorino Respighi’s early development and compositional output. Moreover, it was Respighi’s determination to uphold these Frescobaldian practices, through a variety of fresh approaches over the next years, which color his music in a unique and vibrant fashion.

Title: Suite for strings, P. 41

Total Duration: 27 minutes

Movement 1. Ciaccona: Grave (quarter = c. 50)—Allegro (quarter = c. 84)

Duration: c. 7 minutes

Movement 2. Siciliana: Andantino (dotted quarter = c. 63)

Duration: c. 6 minutes

Movement 3. Giga: Presto (dotted quarter = c. 76)

Duration: c. 3 minutes

Movement 4. Sarabanda: Lento (quarter = c. 40)

Duration: c. 3 minutes

Movement 5. Burlesca: Vivace (quarter = c. 96)

Duration: c. 4 minutes

Movement 6. Rigaudon: Allegretto (half = c. 96)

Duration: c. 4 minutes

The Suite for strings (1902) in G minor is also in Baroque style, but it provides some lovely surprises. Though it is conventional in form, the Suite contains several intriguing experimentations that support Respighi’s later, more mature compositional style. The Suite is the first significant occurrence of Respighi’s practice of combining pre-classical melodic styles and formal structures, such as dance suites, with standard or idiomatic late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century romantic harmonies and textures—a special technique which Respighi improved over time. In fact, this is one of Respighi’s very first renderings of such a perfectly balanced combination of “old-meets-new.”

While the Aria is more purely Baroque than Romantic in style, notwithstanding its persistence for dramatic attention, the Suite defines Respighi’s foundations as a forward thinking musician. Nonetheless, this early moment confirms the Bolognese composer’s innate calling or propensity for antiquity. It is no wonder that, with a mastery of these traits, he became a true exponent of Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque classical traditions by the end of his career.

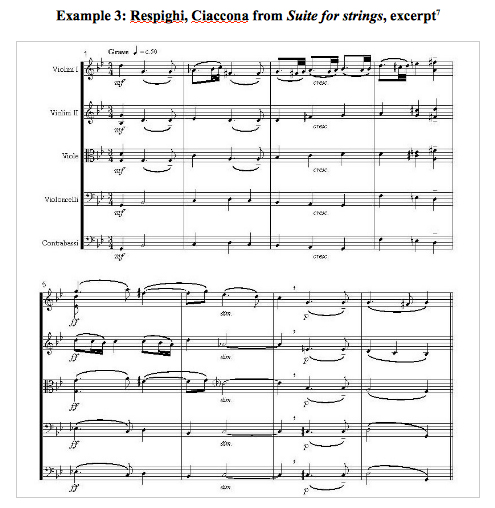

The Suite’s first movement, “Ciaccona,” opens in a reflective, solemn manner in a slow tempo, which later shifts to unexpectedly quick tempi in the concluding variations. As in any Baroque chaconne, the theme develops over an underlying harmonic progression. However, despite the stark minor beginning, the central section of this movement is almost entirely in major. With seventeen variations altogether, the Ciaccona is the longest movement in the Suite.

Example 3, Respighi, Ciaccona from Suite for strings, excerpt.7

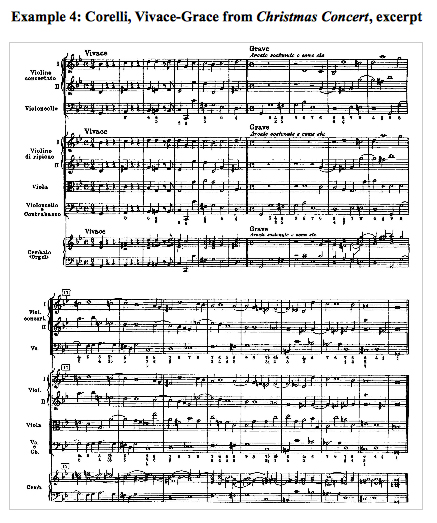

Here we are enticed by Respighi’s memory of Arcangelo Corelli’s music, such as the low heavy pulse of a Grave or Largo movement from a prominent concerto grosso, for example the “Christmas” Concerto Grosso in G minor, or the Trio Sonatas.

Example 4, Corelli, Vivace-Grace from Christmas Concert, excerpt.

The outer melodic lines of Respighi’s “Ciaccona” continually dominate the overall sound. The music is powerful throughout, more romantic and turbulent than Corelli, even violent at times. It is no surprise then that Respighi also found inspiration in the music of his fellow Bolognese Tomaso Antonio Vitali, who was influenced by Corelli as well. In 1908, Respighi transcribed Vitali’s Ciaccona for solo violin, organ and strings, an eighteenth-century work which anticipated Romanticism.

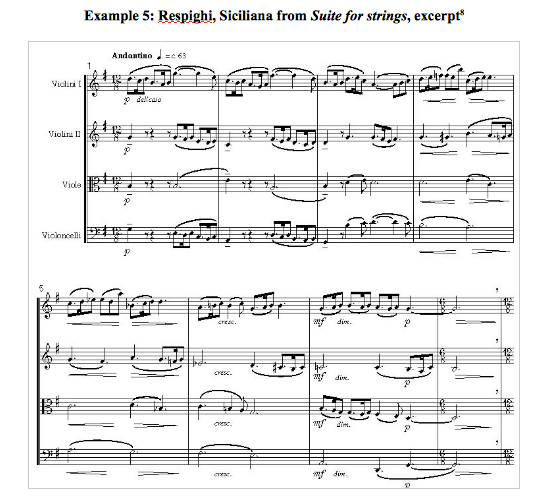

The “Siciliana” second movement, is lighter and quite graceful in character. It embraces a slow gigue-like dance in 12/8 meter, with high soaring notes and melodic turns. This pastoral movement also clarifies certain connections between the Suite for strings and the Aria. Respighi’s later inclusion of the Aria in his Suite in G Major for Organ (1906) was also combined with a “Pastorale” movement that resembles the stately manner of this “Siciliana.” As a group, these works give us a fine account of Respighi’s musical world between 1901 and 1906.

Example 5, Respighi, Siciliana from Suite for strings, excerpt.8

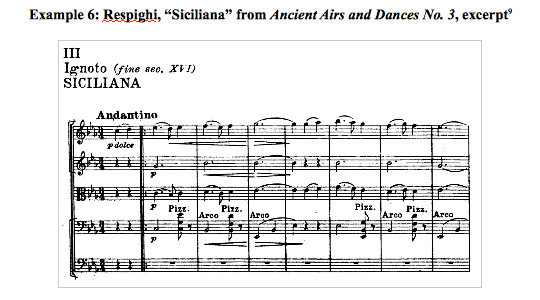

Also moving serenely in G major, the “Siciliana” presents delicate, almost transparent music. The narrative evolves as an Andantino tempo with intended calmness and moments of silence. Again, we are reminded of Corelli, given the inclusion of the “Siciliana” in the Christmas Concerto. However, Respighi’s “Siciliana” is more intriguing than appears at first listening. Traces of this music may be found in the “Siciliana” of Respighi’s later masterwork Ancient Airs and Dances No. 3 for strings through its reflective ambience, short cantabile melodies and regular cadences. Also apparent is the similar play of a melodic third motive by the first violins, descending in the Suite (Example 5: notes D-B-G) and ascending in Ancient Airs (Example 6: notes E flat-G). Respighi develops this motivic idea in a variety of ways, also in other works yet to be discussed such as The Birds.

Example 6, Respighi, “Siciliana” from Ancient Airs and Dances No. 3, excerpt.9

As the basses remain tacet for this movement, one cannot help but imagine this music (perhaps for string quartet) in a festive occasion, as part of a Mozart-styled serenade or divertimento. And like Mozart, Respighi’s youthful “Siciliana” embarks on the sublime, with its sigh-like motifs and noted tranquil resting points.

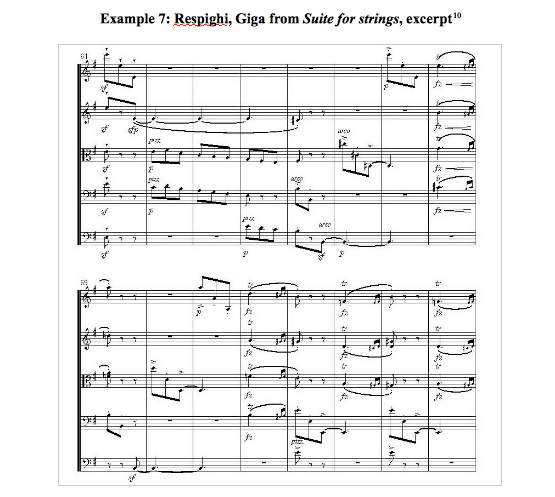

The “Giga” third movement has a rather startled entrance, and immediately establishes a quick (lively) meter, all in a scurry of counterpoint. It is the most modern of all of the Suite movements to be sure. The “Giga” allows Respighi to compose a short, rhythmically interesting, motive that accents and fragments its way from one string section to another, effectively in E minor. Similar to previous movements, an A B A form ensues leading to a brief codetta. We are also surprised by a delightful, dark theme moving in octaves between the second violins and cellos (with basses), which is then greeted by a uniquely characteristic tutti trill passage. The middle section, in particular, highlights this master’s later use of frequent trills and tremolos as principal effects throughout the orchestra. These effects are especially obvious in measures 72-75.

Example 7, Respighi, Giga from Suite for strings, excerpt.10

Through its trills coupled with sforzandi, the “Giga” gives us a glimpse of elements to come later in Ancient Airs as well as Trittico Botticeliano (1927) and The Birds (1928), not to mention Fountains and other important works. The trills and tremolo effects also directly link Respighi to Vivaldi. With this recurring trademark (also noticeable in the later “Burlesca” movement), we may understand the Suite for strings as a sort of bridge for Respighi, connecting such programmatic works as Vivaldi’s Four Seasons to his own The Birds.

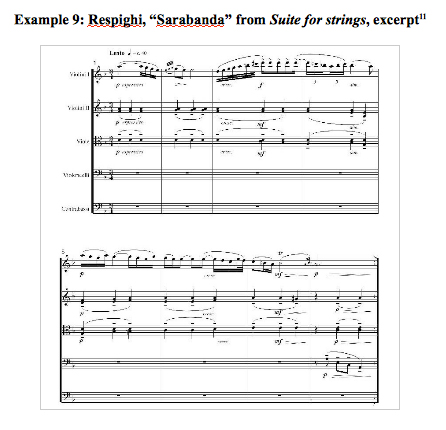

Respighi’s awakening gift of lyricism is most apparent in the “Sarabanda” fourth movement in G minor, with its ever-present tied beats and other sustained sounds. In returning to more serious expressions displayed in earlier movements, Respighi transcends the jovial “Giga” style for a more refined music—another lyrical air. Now we encounter a direct homage to Edvard Grieg, especially his Holberg Suite (1884). Respighi has certainly captured the spirit of Grieg’s masterwork, which was also composed “in the old style.” In both circumstances, sostenuto second violins and violas keep a steady flowing atmosphere, underneath a poignant and graceful theme.

Example 8, Grieg, Air from Holberg Suite, excerpt.

Using similar baroque dances and formal structures, Respighi emulates Grieg’s syncopated pulse, sonorities and harmonies not only in the “Sarabande,” but the forthcoming “Burlesca.” Here, the longing melody of the “Sarabande” is no doubt greatly inspired by the written-out turn motif in Grieg’s “Air” (as we can identify in the first two measures of Examples 7 and 8). Also, similar to Grieg’s Air, the B section of Respighi’s melody (not shown) involves a descending violin line with a triplet grace note resolution, and concludes with an emerging dark statement by the cellos. Notwithstanding the magic of this music, Respighi’s sensibilities for melody or sheer lyricism control all aspects of the composition. Yet there is a certain youthful, almost rugged quality about this music which lends itself more easily to southern than northern European Baroque models, that is, Italian and French (Mediterranean) over German and English (Nordic) influences.

Example 9, Respighi, “Sarabanda” from Suite for strings, excerpt.11

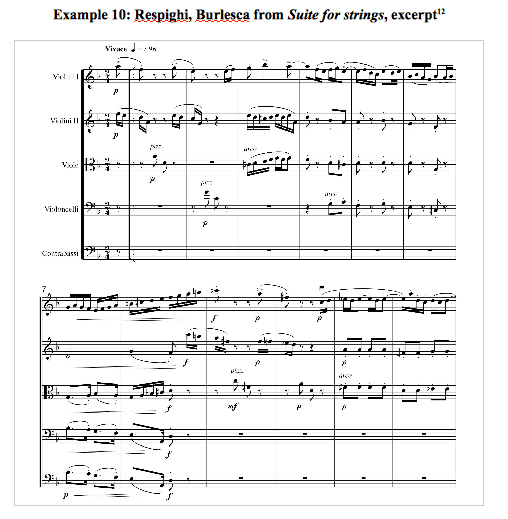

The fifth movement, a nineteenth-century style “Burlesca” in D minor, is more playful in character from beginning to end. As a scherzo of sorts, it is to some extent related to the “Giga” movement, especially with its fragmentation of motives dispersed throughout the string ensemble.

Example 10, Respighi, Burlesca from Suite for strings, excerpt.12

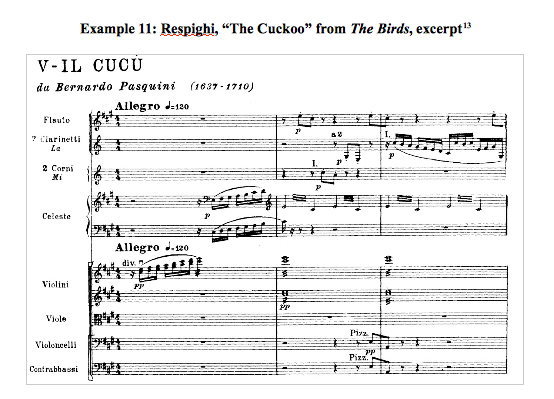

More importantly, we are again witnessing a prelude to The Birds, specifically its capriccio-like “Cuckoo” (fifth) movement. Like the “Cuckoo,” the “Burlesca” is dominated by a two-note descending melodic third motive, and this is reminiscent of the above-mentioned melodic thirds in the “Siciliana” of both Suite and Ancient Airs. (Examples 10-11, then 5-6).

Example 11, Respighi, “The Cuckoo” from The Birds, excerpt.13

This music may be academic or formal in essence but it nonetheless remains somewhat virtuosic for all of the performers involved. At the heart of Respighi’s musical essence, we are overwhelmed with elegant harmonies and rich ornamentation—purely inspired out of the Baroque. And yet, this movement allows Respighi additional play for modern subtleties including accents of syncopated rhythms and quick changes in dynamics, common in later works.

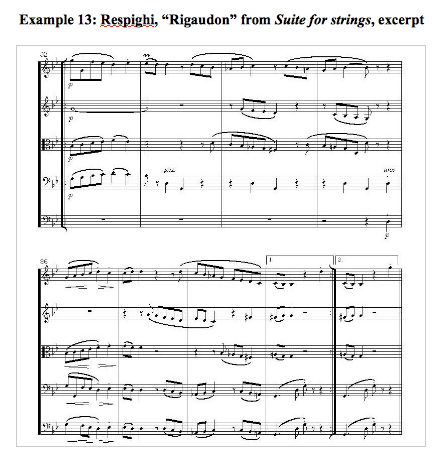

Like Grieg’s finale to Holberg Suite, the Suite for strings concludes with an energetic “Rigaudon” movement. This music abruptly changes the character with a lively duple meter, and strict and declamatory almost vocal-like melodies. Following in the footsteps of the “Burlesca,” and foreshadowing The Birds “Cuckoo” movement, the “Rigaudon” also features a developing variation of a descending melodic third motive.

Respighi then opens the slow, middle section of this movement with an almost exact replica of the melody of the slow section in Grieg’s “Rigaudon” (Examples 11 and 12).

Example 12, Grieg, “Rigaudon” from Holberg Suite, excerpt.

Respighi’s “Rigaudon” is structured as a complete scherzo, which combines an A-B-A song form with a shorter “trio”-like section, thus creating two large sections within a single movement. The Trio returns the Suite back to G minor, the same key used for the beginning of the first movement “Ciaccona.” But the expected return to the “scherzo” section brings the Suite to close in G major.

There can be no doubt that Respighi’s Suite for strings was written in homage to Grieg’s Holberg Suite. Both the “Sarabande” and “Rigaudon” in Respighi’s Suite encapsulate numerous features of Grieg’s “Air” and “Rigaudon,” respectively. Notwithstanding this connection, the resilient spirit of the work provides Respighi with a number of malleable musical devices which (over time) trickle into his more refined moments, not excluding Ancient Airs No. 3 and The Birds.

Example 13, Respighi, “Rigaudon” from Suite for strings, excerpt.

With his Suite for strings, Ottorino Respighi not only moves us to reflect on Edvard Grieg’s music but also allows us keen insight into the master who later composed the well known Ancient Airs and Dances No. 3. As I have explored in this article, the Suite is revealing of Respighi’s mature style on several levels. From the dramatic opening of the “Ciaccona” to its exciting “Rigaudon” conclusion, from the modern “Giga” to the Baroque “Siciliana,” the Suite captures countless resemblances and certain perfect images that are implicitly associated with Respighi’s more memorable, later works. I would argue that the Suite for strings remains a clear precursor of the third Ancient Airs Suite, if not The Birds.

This essay has the dual purpose of introducing the new Respighi editions, and providing a review of the musical styles of selected early compositions and their relationship to pre-existent compositional models as well as Respighi’s later music. As demonstrated, there is an undeniable relationship and musical cohesion between the works discussed here, and their common musical elements clarify the relationship between Respighi's early flowering as a composer and his future iconic identity.

Bibliography

Battaglia, Elio et al. Ottorino Respighi. Turin: Eri Edizioni, 1985.

Cantù, Alberto et al. Respighi Compositore. Turin: Edizioni Eda, 1985.

Pedarra, Potito. II Pianoforte, Nella Produzione Giovanile di Respighi. Milano: Rugginenti Editore, 1995.

Notes

1I examine the recently published, rediscovered Concerto for Violin in A Major (1903) – now considered Respighi’s first violin concerto—in a forthcoming article.

2Respighi museum archives include: International Museum and Library of Music, Bologna; State Archive of Milan, Morgan Museum and Library; and private Respighi family archives (Elsa and Gloria Pizzoli; Potito Pedarra).

3Edizioni Panastudio has published these early works of Ottorino Respighi in their series, Ottorino Respighi Publications. I have served as editor for these editions. For further musicological research of these scores, please contact: Edizioni Panastudio, Via La Mantia, 72, 90138 Palermo (Italy)—Tel.: (39) 091.325284; Fax: (39) 091.9825639 www.panastudio.it.

4Respighi’s works have been catalogued in chronological and categorical order (genre) by Potito Pedarra. Each opus is listed with a P. for Pedarra. The entire catalog list is available online at www.ottorinorespighi.it.

5The recently published edition of the Aria makes the work accessible for not only string orchestra but string quintet, suitable in academic settings.

6Ottorino Respighi: Aria per archi, P. 32, trans. Salvatore Di Vittorio. Palermo: Edizioni Panastudio, 2010.

7Ottorino Respighi: Suite per archi, P. 41, rev. Salvatore Di Vittorio. Palermo: Edizioni Panastudio, 2010. (The autograph manuscript is preserved at the International Museum and Library of Music, Bologna.)

8Ottorino Respighi: Suite per archi, P. 41, rev. Salvatore Di Vittorio. Palermo: Edizioni Panastudio, 2010.

9Ottorino Respighi: Ancient Airs and Dances. Rome: Casa Ricordi, 1928.

11Ottorino Respighi: Suite per archi, P. 41, rev. Salvatore Di Vittorio. Palermo: Edizioni Panastudio, 2010.

13Ottorino Respighi: Ancient Airs and Dances. Rome: Casa Ricordi, 1928.