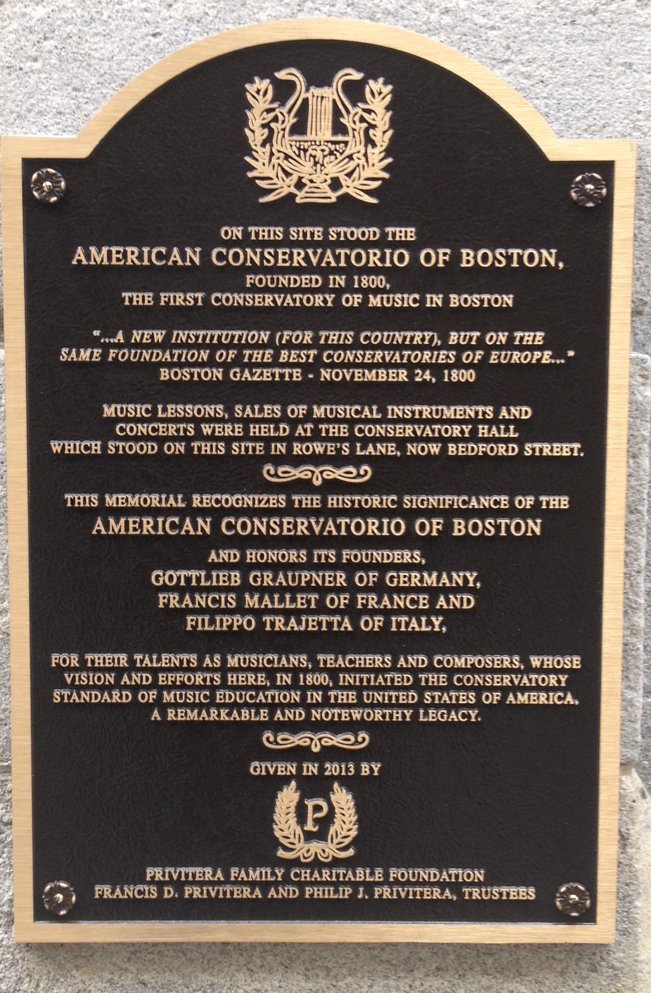

Boston, 30 December 2013. At about noontime, a service van stopped near an office building in busy Bedford Street. Two gentlemen stepped out of the vehicle and, without much ado, affixed a plaque to the façade of the building as tourists and locals on their lunch break paused to read it:

That day was a dream come true for Teresa (Terri) Mazzulli, a woman who harbors a strong passion for Boston’s hidden cultural treasures. Terri’s overwhelming civic pride and dedicated persistence has brought to the attention of Bostonians the nearly forgotten names of Gottlieb Graupner, Francis Mallet, and Filippo Trajetta, three musicians from Germany, France, and Italy who envisioned and, indeed, created the first music conservatory in their newly adopted country; the American Conservatorio of Boston.

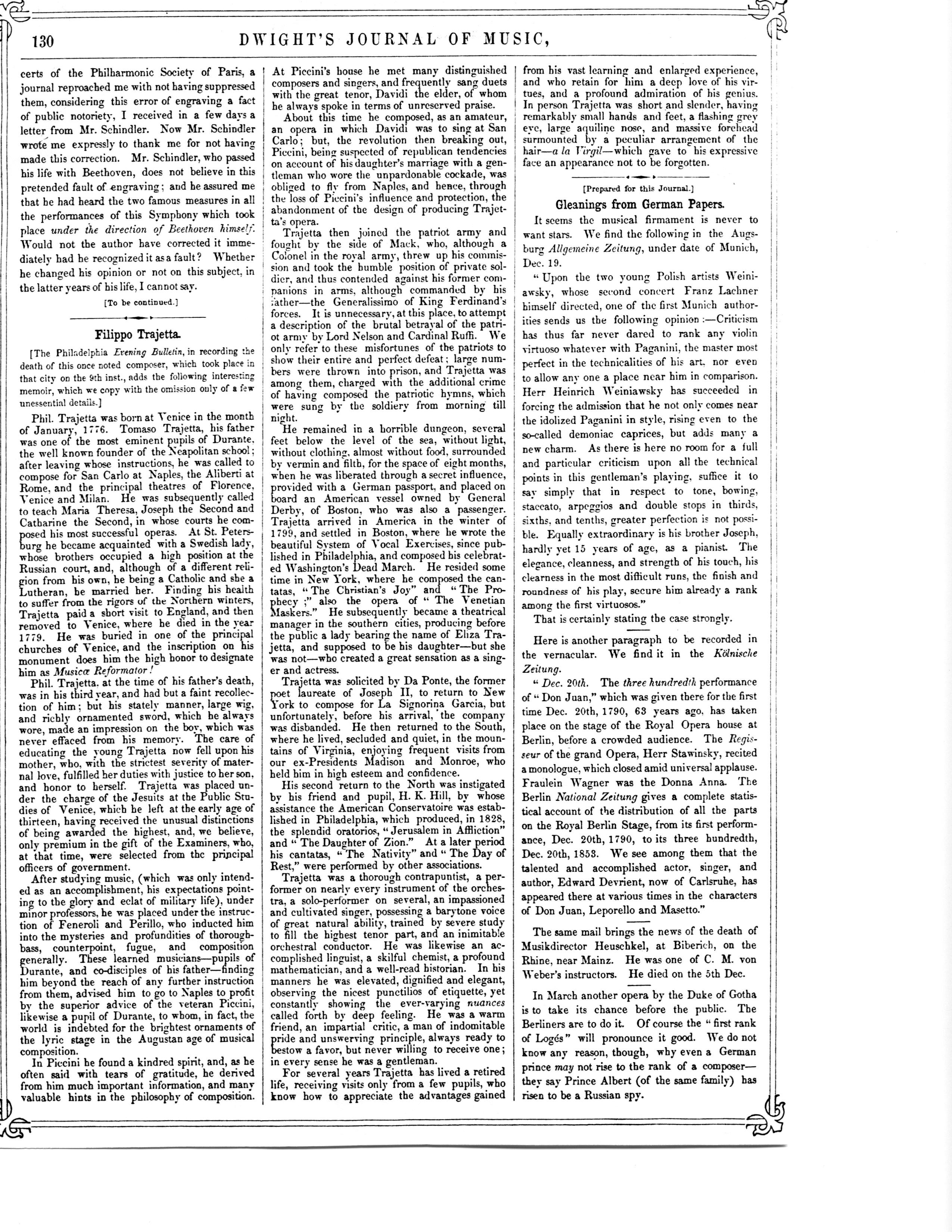

While the citizens of Boston think about the prolific lives of these three European musicians on 10 January 1854, the citizens of Philadelphia read in the pages of the Evening Bulletin that Phil Trajetta, one of their finest residents had passed away. The notice bounced quickly from Philadelphia to Boston, where the highly regarded Dwight’s Journal of Music reprinted the whole obituary.

Philadelphia 1828 - 1854

Philadelphia 1828 - 1854

Phil Trajetta traveled from Virginia to Philadelphia in 1828. It is quite possible, however, that he paid visits to the city earlier in order to plant the seeds for the American Conservatorio of Philadelphia. In the late 1820s the traveling distance between Virginia (Norfolk, Petersburg, and Richmond) and Philadelphia was well serviced by a “Line of Packets” departing to and from both destinations on a weekly basis and at an affordable cost. At any rate, the Aurora & Pennsylvania Gazette of Philadelphia of 1 May, 1828, issued a list of addresses whose unclaimed pieces of mail were held at the post office for pick-up; an unspecified item addressed to Philip “Tragetta” awaited its rightful owner. He must have retrieved his mail since he was no longer listed on a similar advice notice dated 31 May. Unclaimed mail for Philip “Trajettor,” Philip “Trajitta,” as well as Philip “Trajitter” continued to appear in the pages of the same paper on 16 and 31 October and 16 November, when finally he must have acquired a permanent address.

In 1828 Philadelphia represented a natural hub for the fifty-one-year-old musician. He was a mature gentleman who had reached the fateful crucible typical of the emigrant’s tale: a life equally divided between the motherland and the adopted country. Philadelphia represented for him the dawn of a new existence and, after years of uncertain peregrinations, his final destination.

As mentioned before and judging from the mail addressed to him at the Philadelphia Post Office, Phil Trajetta was residing in the city in 1828 and directing the already established American Conservatorio, notwithstanding the lack of press announcements about the event. Proof of this assertion is found in a minute book of the Musical Fund Society, now stored in a bank vault of the Girard Trust Company in Philadelphia. A note among the minutes reported that “the Musical Fund Society at a special meeting on 31 October 1828: Resolved that the conductor of the American Conservatorio [Trajetta] be allowed the use of the kettle drums and double bass they being accountable for any damage they may sustain while in their service.”1 Finding this important document confirmed that Trajetta was indeed directing the American Conservatorio of Philadelphia in 1828 and that he was taking steps, by securing the necessary instrumental equipment, to plan the first performance of his oratorio The Daughter of Zion scheduled for 10 February 1829. The Musical Fund Society’s deliberation indirectly depicted Trajetta as a musician and musical operator with an independent mind who wished to cultivate a good relationship with the premier musical organization in the city. Furthermore, the front cover of Trajetta Eight Small Progressive Chorusses [sic], published in 1846, states in bold letters that the work was originally conceived for the American Conservatorio of Philadelphia A.D. 1828.

The Musical Fund Society, whose imposing building on Locust Street is a reminder today of Philadelphia’s past glories, was founded in 1820 and was conceived primarily as a charitable association for needy musicians. Interestingly the backbone of the Musical Fund Society was the Quartet Party, a string quartet organized by Charles Hupfeld in 1809. Members of this group were the violinists George Gillingham and Charles La Folle, a Parisian who had studied with Rodolphe Kreutzer; violist John C. Hommann,Sr.; and cellist J.C.G. Schetzky. The Quartet Party became the nucleus of an orchestra that, when joined by a chorus, performed two concerts per year. In a statement issued on 2 May 1820, the Society comprised 164 members with musicians, contributors, and two medical doctors available to those and their families who needed their services.2 Those of financial means were allowed to purchase stock in the Society. The Musical Fund Society produced during the 1823-1824 season The Creation and The Seasons of Haydn and the Dettingen Te Deum and Messiah by Handel. For many years its annual production of Handel’s Messiah galvanized local professional and amateur musicians alike.

In 1825 the Society instituted as a music school the Academy of Music (not to be confused with the homonymous association founded in 1857), but it ceased activities in 1832. It is possible that the demise of the Academy of Music was caused by competition with Trajetta’s American Conservatorio. It is interesting to note here that, while the Academy of Music routinely purchased advertising space in Philadelphia’s newspapers for the recruiting of students, the American Conservatorio abstained from such a practice.

The reputation of Trajetta must have been sufficient to fill the faculty teaching schedules without further solicitation.

In the course of his twenty-six years spent in Philadelphia, Filippo Trajetta, now familiarly known as Phil Trajetta, was a witness to and sometimes a participant in many economic, cultural, and social changes taking place in the city. Philadelphians had created the institutions and laid the foundations for the great scientific and industrial city that was to come, while at the same time achieving a higher level of intellectual and artistic life that made their city known as the “Athens of America.”3

It must have been this genteel and gentrifying climate that prompted a chosen clientele to seek musical instructions from those professionals who employed well-proven European methods. In Trajetta’s specific instance, his name alone represented a glorious ancient tradition: the Neapolitan school of Niccolò Piccinni, of his own father Tommaso, and of their teacher Francesco Durante especially in the field of sacred music as shown ahead.

The “American” Oratorios

An ornately designed notice was prominently reproduced in the Aurora & Daily Advertiser of 5 February 1829. It announced to the inhabitants of Philadelphia that the members and pupils of the American Conservatorio were offering at the Saloon of the Musical Fund Society the first performance ever of The Daughter of Zion, an oratorio composed and conducted by Trajetta. The event, which was to take place on the evening of 10 February, proved to be a landmark: it was Trajetta’s official debut in his new hometown as well as the initial presentation of the first oratorio composed in America. The composer himself wrote the text, drawn from the Old Testament. This was the beginning of a glorious American oratorical season that reached its apogee at century’s end with Horatio Parker’s masterpiece Hora Novissima.4 The event must have been greeted with great public approbation since Trajetta and his organization promptly advertised two more performances of the same work scheduled for 17 and 23 April.

One year later the Philadelphia Gazette & Daily Advertiser announced that on Tuesday afternoon, 23 March 1830, a public performance of the second grand-scale oratorio from Trajetta’s pen would take place: Jerusalem in Affliction. Trajetta’s second oratorio, Jerusalem in Affliction is more massive than The Daughter of Zion. Its structure and instrumentation are those of a sacred military oratorio, one based on Biblical account of the Israelites in Egypt and the Exodus, a subject also used by George Frideric Handel for Israel in Egypt.

In broad stylistic terms, Trajetta’s music reflects the composer’s admiration for Handel and Haydn filtered through the Catholic teachings of his forefathers Durante and Piccinni. His most important contribution to American music resulted, therefore, in the transplantation of Italian and Anglo-Saxon traditions, which in his particular case united Lutheran beliefs to Jesuit teaching methods. In sum, Phil Trajetta’s music, although not innovative in contrapuntal structures and harmonic language, served the American musical environment of his time as a codifying agent of things past and as an intellectual springboard for launching novel ideas.

The Pedagogue

An Introduction to the Art and Science of Music, published for the first time in 1829, reveals Trajetta’s assessment of the philosophical balance between the practical and pedagogical aspects of music performance reflected in the two oratorios, The Daughter of Zion, and Jerusalem in Affliction, and of the basic knowledge of music theory that he deemed necessary for good musicianship. This treatise appeared in three editions published in 1829 (Philadelphia: I. Ashmead & Co.), 1860 (Philadelphia: Beck & Lawton), and 1873 (Philadelphia: J. Storrs & Holloway). The preparation of good musicians, those “easier to teach if equipped with good theoretical notions,” was Trajetta’s first and foremost pedagogical mission at the American Conservatorio and the principal motivation for writing his treatise. An Introduction to the Arts and Science of Music was not the common self-paced tutor typically available during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, but a precious book to be discussed, point-by-point, in a classroom setting with one’s teacher. He wrote it for the pupils of the American Conservatorio of Philadelphia, his own school branded by his own philosophy and pedagogical orientation. If some notions presented in this book still seem vague, oral persuasion or, as Trajetta pointed out in the Preface, reasoning, would have certainly clarified the matter. Through its three editions, spanning more or less half a century, Trajetta’s book was taken into high consideration by three generations of American professional musicians and music lovers.

As late as 1882 Trajetta’s staunchest supporter, James Cox Beckel invoked his teacher’s name and sacrosanct rules of harmony and counterpoint several times in the course of a curious diatribe launched by the seventy-one-year-old Beckel against Hugh Archibald Clarke. Beckel issued a Dissertation on the Minor Scales, Roots, Thorough Bass and Modulation,5 which was a point-by-point critique of Clarke’s Harmony on the Inductive Method published in 1880.6 Although only Part One (“On the Minor Scale”) was ever published, Beckel’s argument, based on the writings of many preeminent theoreticians and Phil Trajetta’s in particular, deserves to be examined in detail separately at another time; for now, it is important to notice that Beckel cited Trajetta’s An Introduction to the Art and Science of Music and Scales and Formulae, which were available, he stated, in his own Guide to Thorough Bass and Harmony, Book I. Therefore, it is evident that Beckel’s treatise (no copies have resurfaced as yet) was based on annotations Trajetta had gathered for the projected publication of those theoretical books he had announced in his Introduction.

Although Phil Trajetta continued to publish musical and theoretical works until 1846 without affixing the imprimatur of his beloved school, The Eight Small Progressive Chorusses [sic], published in 1846, told the music community, almost nostalgically, that they had been indeed composed for the American Conservatorio of Philadelphia but, much earlier, in 1828.

Several years before his death Trajetta divested himself of professional responsibilities, receiving visits only from a few pupils like the ever faithful James Cox Beckel and Albert G. Emerick. Beckel was a practical musician, gifted with a strong intuition for business. He moved around Philadelphia continuously, changing the address of his place of business according to the city’s developing new demographics. He seemed determined to bring most of the works of his teacher back to life in newly published formats. Some of Trajetta’s works were published and republished under his supervision, while others remained unfinished projects that his publishing house duly advertised not as forthcoming but as available for purchase. Not materializing when demand fell short, the works never saw the light. This was probably a precautionary business practice, one might say, but certainly not one to the advantage of the scholar who wonders what kind of product Beckel had at hand, ready for the presses, and what happened to it after its withdrawal.

Much less involved in the music business than his colleague Beckel was Albert G. Emerick, organist at St. Stephen’s Church. According to Robert A. Gerson, Emerick “taught many pupils between 1830 and 1860. He performed and managed an important series of concerts from 1850 to about 1860, preceding those run by Michael Cross and Charles H. Jarvis. Emerick was born in Philadelphia in 1817 where he died in 1898. He was an associate of such organists as John C. Standbridge and W. H. W. Darley in the years before the Civil War.” Emerick was a man of vast intellectual capabilities and the owner of an accurately selected music library.

In the years following Trajetta’s leadership in musical life, the availability of musical instruction in the city continued to strengthen and grow. Robert A. Gerson, in his survey Music in Philadelphia (1940), identifies important developments and significant figures succinctly:

“The addition of large music schools to an increasing number of independent teachers of music reflects the growth and spread of the city’s population between 1865 and 1940. Three conservatories which are still leading music schools were founded between 1870 and 1885. The Philadelphia Musical Academy, organized in 1870, is the oldest of these conservatories. The Philadelphia Conservatory was established in 1877, and the Combs Broad Street Conservatory in 1885. As each of these music schools plays a large part in the musical instruction of the present time, a short account of their history and organization is given. John Himmerlsbach founded the Philadelphia Musical Academy in 1870. When he resigned in 1876 to return to Germany, Richard Zeckwer filled his position as head of this school until 1917 when he was succeeded by his son Camille. The Hahn Conservatory merged with the Philadelphia Musical Academy in 1917, and since that year the conservatory has been called the Zeckwer-Hahn Philadelphia Musical Academy. Frederick Hahn, the son of Henry Hahn, who was also a noted violin teacher in Philadelphia, has been president of this school since 1924.”7

The merging, confluence, and gradual transformation of these institutions, in addition to the many private teachers whose advertising appeared in the city’s newspapers, served to give shape to present-day Philadelphia’s world-renowned music schools. One should remember, however, that it was Phil Trajetta’s American Conservatorio that has stood as the beacon of musical instruction in a great American city’s centuries-old traditions.

Final Journey and Musicological Revival

The Evening Bulletin of 10 January 1854 informed its readers that Phil Trajetta’s body was to be buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery. This place of rest, inaugurated in 1849, was situated on the northwest side of Islington Lane, that is to say, northeast of Ridge Avenue. Philadelphia’s population, 400,000 strong by mid-century, continued to grow so rapidly that in 1865 the Odd Fellows Cemetery acquired a further parcel of land, later referred to as Mount Peace. It occupied both sides of Diamond Street west on 22nd Street. Beginning in 1894, with the opening of 25th Street, between Norris and Diamond Street, the Mount Peace portion of the cemetery was dismantled. In 1907 the exhumed human remains were reinterred in Lawnview Cemetery in Rockledge at the periphery of the city. In 1951 the original site of the Odd Fellows Cemetery was acquired by the municipality of Philadelphia and, once transformed, was prepared for the construction of The Raymond Rosen Housing Development. In a comparable process, the remains of 65,000 bodies were exhumed and again transferred to Lawnview Cemetery. In more recent times the Rosen Housing Development has been replaced by the present Community Recreation Center.

According to data preserved on microfilm, the plot originally assigned to Trajetta at the Odd Fellows Cemetery was Section 5, Lot 52. Unfortunately, this is the last known information concerning the whereabouts of Phil Trajetta’s remains. Furthermore, his name has disappeared from the ledgers preserved at Lawnview Cemetery.

In the year 2000, the civic minded cultural association “Tommaso Traetta” of Bitonto, a thriving olive oil producing town in Apulia, Southern Italy, asked me to investigate the life and works of Filippo (Phil) Trajetta, the son of Tommaso Trajetta (Traetta) their most celebrated citizen whose life-size marble statue proudly watches over the town’s main square. As a result, I wrote a book entitled Filippo Trajetta: un musicista italiano in America, which was published by Adda Editori in 2002. Years later, a much-expanded version of Trajetta’s biography appeared in English under the title Phil Trajetta (1777-1854): Patriot, Musician, Immigrant (CMS Monographs & Bibliographies in American Music No. 22, 2010).

For this volume, I broke down the obituary’s narrative into chronological episodes and followed them, reconstructing facts and clarifying ambiguities by researching chronicles, concert programs, correspondences, and Trajetta’s extant works in print and manuscript. Ultimately, I added a newly edited anthology of Trajetta’s most relevant compositions. Thus, Trajetta’s adventurous life, political ideologies, Masonic associations, travels, and exceptional career emerged as a portrait of the “new American artist/intellectual.”

Unlike commemorative monuments, plaques, and the naming of streets, squares and buildings, books often go out-of-print, rest on shelves or just become catalogue’s entries. Occasionally, though, publishers issue reprints or revised second editions. In Trajetta’s case, although a second edition of the currently-out-of-print book in English would be highly desirable, one would wish that the unveiling of the commemorative plaque in Boston, where his American career began, would ignite a renewal of civic pride in Philadelphia, the city where Trajetta’s career and life came to a close.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Charles R. Barker. Philadelphia Cemeteries [unpublished manuscript] Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Filippo (Phil) Trajetta’s Music Manuscripts [3 boxes] Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Secondary Sources

Beckel, James Cox. Dissertation on the Minor Scales, Roots, Thorough Bass and Modulation, Part I. Washington, DC: Music Division, Library of Congress. (Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music–1870-1885; http://memory.loc.gov).

Clarke, Hugh A. Harmony on the Inductive Method. Philadelphia: Lee & Walker, 1880).

Gerson, Robert A. Music in Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Theodore Presser, 1940; reprinted Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1970.

Grimes, Calvin Bernard. American Musical Periodical, 1819-1852; Music Theory and Musical Thought in the United States, Ph. D. dissertation, University of Iowa, 1974.

Hermann, Myril Duncan. Chamber Music by Philadelphia Composers, 1750-1850. Ph. D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1977.

Kent, R. M. A Study of Oratorios and Cantatas Composed in America before 1900. Ph. D. dissertation, University of Iowa, 1974.

Krummel, Donald William. Philadelphia Music Engraving and Publishing, 1800-1829. Ph. D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1958.

Madeira, Louise Cephas. Annals of Music in Philadelphia and History of the Musical Fund Society from its Organization in 1820 to the Year 1858 (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincot, 1896; reprinted New York: Da Capo Press, 1973).

Sciannameo, Franco. “Percorso storico-biografico della vita e delle opere di Filippo Trajetta.” Parte I in Studi Bitontini No. 69, 2000: 85-102.

-----------------------. “Percorso storico-biografico della vita e delle opere di Filippo Trajetta, “ Parte II in Studi Bitontini No. 70, 2000: 37-58.

-----------------------. Filippo Trajetta: Un musicista italiano in America (1777-1854) (Bari: Mario Adda Editore, 2002).

-----------------------. Phil Trajetta (1777-1854), Patriot, Musician, Immigrant [CMS Monographs & Bibliographies in American Music No. 22] (Hillside, NY: The Pendragon Press, 2010).

Smither, Howard E. The Oratorio in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Volume 4 of A History of the Oratorio (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

Swenson-Elridge, J. E. The Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia and the Emergence of String Chamber Music Genres Composed in the United States, 1820-1860 (Ph. D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1995).

Weigley, Russell F. , Nicholas B. Wainwright, and Edwin Wolfe. Philadelphia: A 300 Year History, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982).

Notes

1Hermann, Myril Duncan. Chamber Music by Philadelphia Composers, 1750-1850. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, 1977, 144.

2The history of the Musical Fund Society has been chronicled in detail by Louis Cephas Madeira in his Annals of Music in Philadelphia and History of the Musical Fund Society from its Organization in 1820 to the Year 1858 (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincot, 1896; reprinted New York: Da Capo Press, 1973); and in recent times by J. E. Swenson-Elridge, The Musical Fund Society of Philadelphia and the Emergence of String Chamber Music Genres Composed in the United States, 1820-1860 (Ph. D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1995).

3See among the vast literature on the history of Philadelphia, John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania on Olden Times (1843), 2nd ed., Willis P. Hazard (Philadelphia: E. S. Stuart, 1884); and Philadelphia: A 300 Year History, ed. Russell F. Weigley, Nicholas B. Wainwright, and Edwin Wolfe (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982).

4For a detailed study of the oratorio in America, see R. M. Kent, A Study of Oratorios and Cantatas Composed in America before 1900 (Ph. D. dissertation, University of Iowa, 1974); and Howard E. Smither, The Oratorio in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Volume 4 of A History of the Oratorio (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

5James Cox Beckel, Guide to Through Bass and Harmony, Book I (Philadelphia: J. C. Beckel, 2 South 11th St.).

6Hugh A. Clarke, Harmony on the Inductive Method (Philadelphia: Lee & Walker, 1880). Born near Toronto, Canada, Clarke was appointed in 1875 professor of music at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, one of the first such appointments in the United States. The other, John Knowles Paine, was appointed at Harvard in the same year. See John D. Mahoney, “Dr. Hugh A. Clarke, Musician,” The General Magazine and Historical Chronicle XL VIII (April 1941), 348-60.

7Robert A. Gerson, Music in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Presser, 1940), 299