Abstract

There has been much discussion and research in recent years about the types of careers our recent music graduates have been leading. Scholarly work suggests that the current undergraduate curriculum may not prepare musicians to function successfully in the 21st century. Some conservatories and universities operate entrepreneurship programs to assist students with the development of business and career skills. However, students may not recognize the need to explore their musical identities and future roles as musicians while pursuing coursework. This article explores real-world skills that students should develop during undergraduate studies and ways in which faculty might engage students in preparing for various professional roles in the 21st century.

Background and Context

Introduction

In the United States, an undergraduate degree has increasingly become a minimum requirement for entry-level professional employment and for increased earning potential over the course of a lifetime.1 Due to rising tuition, reported high rates of unemployment among college graduates, and general increased demand for accountability, many degree programs have been assessed almost solely in terms of economic parameters often by using ill-defined ratios that compare affordability, graduation rates, employment, and long-term earning potential of a school’s graduates.2 While the bachelor of music (BM) degree is considered to be a professional degree that prepares students to work in the musical field upon graduation, there is some debate about how well current programs accomplish this goal.

The National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) cites 15 professional undergraduate four-year degree programs in music (as diverse as performance, pedagogy, music technology, and worship studies).3 These degrees normally require at least 65% of the content to be in music and it is recommended that the common content be oriented “toward advanced development of general musicianship.”4 While it is acknowledged that “musical performance is normally a factor in determining eligibility for entrance to all undergraduate degree programs,”5 several of the professional degrees, particularly performance, pedagogy and jazz studies, have numerous performance standards that must be met by completion of the degree. However, regardless of the specific program, there are six components of performance content recommended for all professional four-year degrees, including continued “performance study and ensemble experience throughout the baccalaureate.”6 Yet, recent scholarship reveals that recent graduates who have earned bachelor of music degrees from conservatories and music schools throughout the world are engaging in music careers that include far more diverse activities than performing and teaching, despite the prominence of these components in the typical undergraduate performance and pedagogy curricula.7 This paper explores skills, which experts suggest undergraduate music students, particularly those enrolled in performance programs, need in order to engage in successful careers upon graduation and suggest developmental activities that can be included within the current curriculum.

Current Professional Preparation: The Bachelor of Music Degree & Musical Synthesis

The NASM Handbook suggests that, regardless of area of specialization, the purpose of the professional undergraduate degree is to help students:

to develop the knowledge, skills, concepts, and sensitivities essential to the professional life of the musician. To fulfill various professional responsibilities, the musician must exhibit not only technical competence, but also broad knowledge of music and music literature, the ability to integrate musical knowledge and skills, sensitivity to musical styles, and an insight into the role of music in intellectual and cultural life.8

The recommendation suggests that while the emphasis and specific content of the bachelor of music degree may vary, integration of musical knowledge is an important common goal. The accrediting body acknowledges that “while synthesis is a lifetime process, by the end of undergraduate study students must be able to work on musical problems by combining … their capabilities in performance; aural, verbal, and visual analysis; composition/improvisation; and history and repertory.”9 There are many ways in which synthesis can be demonstrated, such as through history papers or original compositions. At the undergraduate level, however, since all students are involved in individual lessons and music making through ensembles, performances tend to provide a means of demonstrating comprehensive synthesis of music styles, skills and literature that is common to the undergraduate experience.10 Thus, while not exclusive to the performing area, musical synthesis and creativity are often exhibited through performance. However, an increasing number of scholars contend that, after just eight semesters of undergraduate training, performance ability is not enough to ensure success within the music profession. Rather, additional skills are needed to function as professional musicians in the 21st century.11

Indeed, it could be argued that the current undergraduate bachelor of music degree prepares students for graduate studies in music, rather than for diverse careers in music. Graduate programs train students to perform at a higher level of competency than the undergraduate degree and, at the doctoral level, for positions in academia. However, many of our undergraduates do not pursue graduate-level degrees upon completion of the undergraduate program. Yet, following four years of undergraduate education the majority of our students are unlikely to thrive as solo performers, orchestral players, or chamber musicians in a competitive musical world.12 So, how do we ensure that students who will not become elite performers or who have no desire to teach music in school or in higher education, have a place to make and create music in our world and earn a living wage while doing so? Thus, the questions become: Are we adequately preparing undergraduate students for lives as professional musicians in the real world? And, have they been advised of what 21st-century music careers might entail?13

The Ninth Semester: Professional Life After Graduation

While researchers report that students typically enter music school with a performer identity that tends to be emphasized and developed during formal undergraduate training,14 for the past decade scholars have noticed a shift in the types of careers in which recent graduates are employed. Upon completing extensive case studies of early career trajectories of successful graduates from the Peabody Conservatory, in 2005 Angela Beeching noted that musical careers had become much more diverse than performing and teaching. In fact, most young music professionals now have what has become known as portfolio or protean careers.15 Portfolio careers include a broad range of freelance activities, they demand a high degree of adaptability and flexibility, and require facility with numerous skills that are only tangentially related to music, if at all. Additionally, due to the flattening and interconnectedness of the first world, musical work is no longer limited to one’s geographical location. This means that finding work is less limited, since one need not be confined by “place.” However, the market may be more competitive, as one conceivably could be competing with musicians from across the globe for certain types of work, making effective marketing of oneself and technologically-enhanced communication skills essential.

Essential Musical and Peripheral Skills for the 21st-Century

In addition to the requisite synthesis of musical skills, in order to be successful today, emerging professional musicians must understand their strengths and weakness (professionally, personally, and interpersonally), know about types of jobs in the music industry, think creatively about acquiring musical work, and set realistic short and long-term career goals.16 Recent graduates from a large comprehensive university reported that they wished that their music degree had prepared them more to: write and speak clearly and persuasively; manage projects; and develop business management, technology, and entrepreneurial skills.17 A subset of these survey participants reported that the professional activities in which they engaged regularly included teaching, collaborative performances, business and networking activities.18 Furthermore, they stated that specific training in business skills, educational technology applications, and marketing techniques during the undergraduate program would have been helpful in their professional lives. In addition to generic entrepreneurial skills, researcher Michael Hannan identified a comprehensive list of 82 specific skills that today’s professional musician needs. He placed these skills into ten broad categories:

• performance skills

• stagecraft skills

• aural recognition skills

• notational skills

• theoretical knowledge (music theory, for example, but also includes understanding of cognition, learning, and other theories)

• compositional skills

• technology skills (music specific)

• other technology skills (multimedia, web site design, etc.)

• business skills

• generic skills (communication, creativity, etc.)19

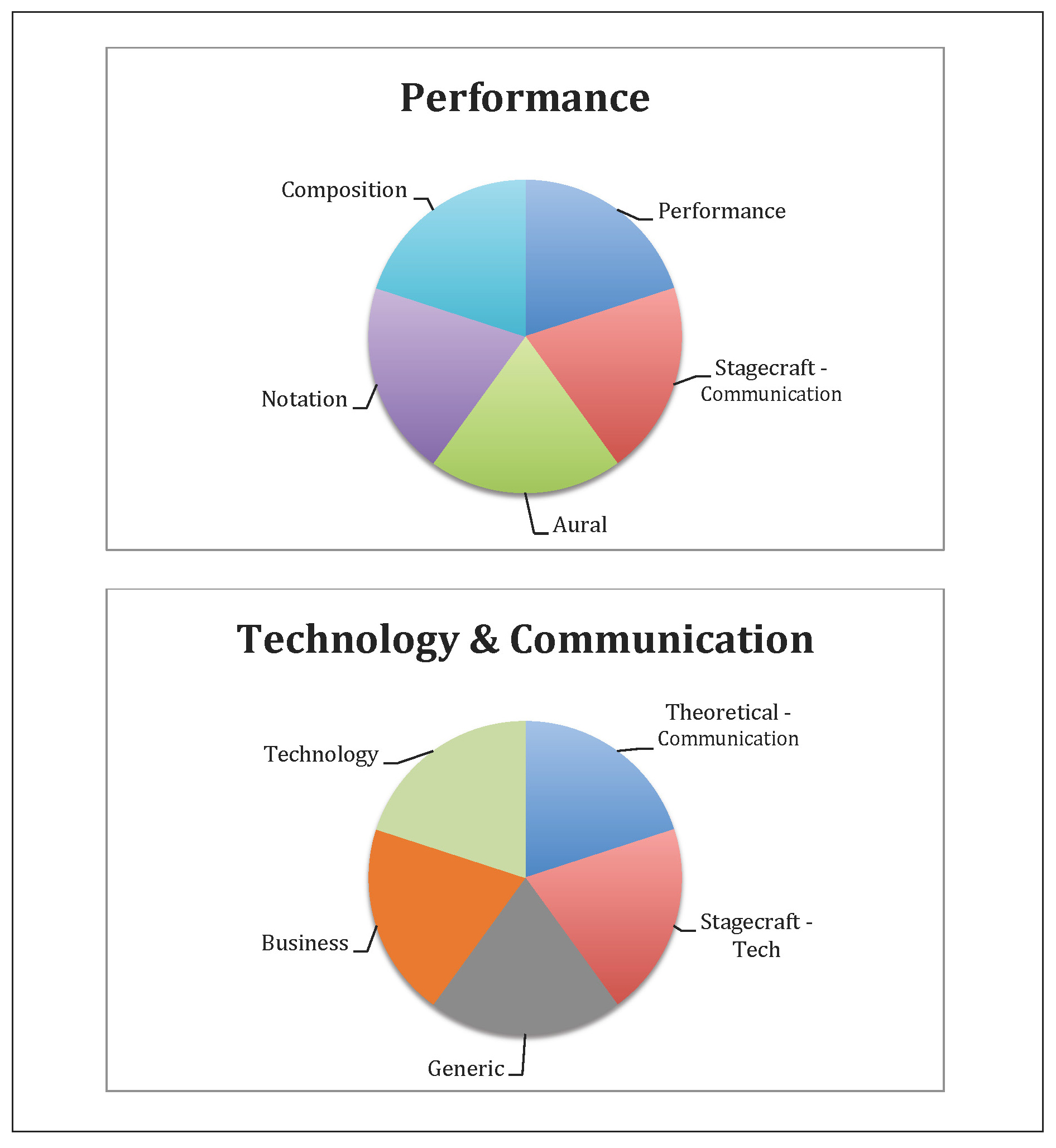

While there are many discrete skills identified by Hannan that need attention, if they are grouped more broadly into the categories of “performance” and “technology and communication,” it may be easier to identify times and places within the undergraduate curriculum where some of these skills could be developed (One possible overview of these skills is pictured in Figure 1). Since there is overlap between some of these categories, there are numerous ways to develop each of these skill sets.

Figure 1. Broad categories of essential musical and non-musical skills adapted from Hannan, “Expanding the Skill Set,” 242-244.

The task of addressing the numerous subsets of skills included in each of these categories might be daunting, but the need exists. For example, in the SNAPP 2011 survey one respondent noted, “more hands-on experience to go with the theory [would have been useful because] I learn by doing not hearing.”20 Another recent graduate said, “the program [and faculty] could have encouraged me to look outside of a performance career, which I ultimately pursued on my own. It [the courses and faculty] could have highlighted the great skills the degree provided me…now I see the value.”21 Although Maris said, “it is not our job to prepare students for specific positions in the music profession,” she suggested that as educators we must help our students to understand areas where their level of achievement will need to be developed (outside of the studio or classroom) if they hope to pursue meaningful professional work.22 Thus, faculty mentoring and career advising become important components in preparing graduates for successful careers. If faculty can help students to understand their unique musical or occupational identities,23 define reasonable career goals,24 develop interpersonal skills and more entrepreneurial thinking25 while in college, they should be more likely to transfer this learning to other areas upon graduation.

Career Advising for Students & Helpful Networks for Educators

While NASM is charged with accrediting curricular programs in schools of music throughout the United States and Canada, there is only one reference to student career preparation: “Advising must address program content, program completion requirements, potential careers or future studies, and music-specific services consistent with … music degrees and programs being offered”26 (italics added for emphasis). Faculty may not always be in the best position to gauge peripheral skills required of young musicians, either because they have enjoyed long, successful careers within the academy (where many of these skills are not necessarily required) or because they are already established in their field and do not face challenges similar to those encountered by recently graduated professionals who have not yet established a foothold in the music profession. While not available at all institutions, numerous schools and conservatories across the United States are establishing entrepreneurship programs.27 At present, there is not necessarily uniformity among the programs. In some institutions for example, student access to services is voluntary and in others where participation is required, curricula may vary. However, several organizations publish information and hold regular conferences that explore career-planning opportunities, present current research on musical careers, and highlight useful activities for young musicians. The networking between tertiary music educators and career development officers creates a beneficial link between the academic and the outside musical worlds. These papers and conference proceedings provide valuable resources for faculty members and administrators of music programs where career services may or may not exist.

A useful resource in North America is the Network of Music Career Development Officers (NetMCDO), which was established in 1995. While most of the career development officers associated with the organization work with classical or jazz musicians, “members provide information, advising, and resources to musicians to advance their careers across the spectrum of the professional music world.”28 Similarly, music faculty from across the globe meet biennially, under the auspices of the International Society for Music Education’s Commission on the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM).29 Part of CEPROM’s mission between 2008 and 2014 has been to “emphasize ways in which to enable present and future educators to employ modes of preparing musicians that reflect an awareness of the continually changing role of the musician in various societies and cultures.”30 Scholars who convene at CEPROM conferences present research findings, converse about important papers in the field, discuss common areas of concern, and engage in collaborative research between meetings. The goal is to help faculty prepare music students for the transition from the academy to professional life. Indeed, much of the scholarship on preparing professional musicians for successful careers has emanated from participants of these particular conferences.

Problem Defined: Possible Solutions

Career Goals and Musical Identities

In 2011, over half of all undergraduate music degrees awarded in the United States were in performance.31 Since it can be difficult to engage undergraduate students, whose primary desire is to become outstanding performers, in acquiring skills that appear to be only tangentially related to music performance, we must encourage students to explore roles and identities of professional musicians, beyond those of elite solo performers. Research has shown that identity exploration at the undergraduate level leads toward clearer and more realistic goal and objective setting by students.32 Perkins has traced how students who evolve in their vision and identity of career and potential achievement during their four years in music school are more likely to experience feelings of satisfaction and success upon graduation.33 She encourages students to examine their musician identities by reflecting on their vision for career success and self-identity (seemingly subjective areas) and through individual interviews with students she probes more objective areas such as how they actually spend their time and how they earn (or will earn) money. She finds that students reevaluate how they might actually earn a living as musicians as a result of this process.

In the United States, one small research study found that piano graduates who are most successfully navigating the first five years as professionals (despite extremely low pay and balancing the varied roles of ensemble performer, teacher, free-lance musician, and teaching-community member) report being satisfied with their work, in part, because they were realistic about what to expect.34 For these particular subjects, pedagogy coursework prepared them for the musical environments in which they would be working and for the varied roles that they would be leading during the first years of professional employment as musicians. A valuable activity during the undergraduate years might be to have students define a professional mission where they craft career goals, challenge assumptions about musical careers, and define (or redefine) professional success, which for most students will need to include more than performance and/or teaching accomplishments.

Dawn Bennett does a variety of exercises during the undergraduate years that encourage students to reflect on their career goals. Bennett has students challenge their stated career goals and articulate specifically how they will define success. She uses a “career matrix” that encourages students to compare their stated passion and skills against those listed on her matrix. Elements of the matrix move from extrinsic to intrinsic motivators and include: education and training, broad base of skills, mentors, experience, openness to change, adaptability to change, industry awareness, peer networks, currency of skills, aspirations and perceptions of success.35 Bennett also does a “Turning on the Career Light” workshop in which students are presented with boxes of objects such as a Viking helmet, sample contract, passport application, grant application, marketing tools, teddy bear, beginning music method books, and other materials.36 Then, in small groups students brainstorm about how these objects might be used in future music careers or about what the items might represent in their careers. Bennett explains that the activity can lead to the development of individual student career plans, action plans, expansion of thinking about what a music career entails, and the need for students to develop an attitude of lifelong learning.37

Another activity that Bennett finds useful is to bring “Career Panels” into classes, where both young and seasoned professionals discuss the varied roles they have assumed throughout their careers. These dialogues can open up new ways of defining career success to students before they embark upon their professional lives. One could also have students go out to interview professionals or be mentored by them. For example, pedagogy students might take field trips to local studios and community music schools to observe various kinds of lessons, peripheral activities beyond teaching, and to ask questions about the business aspect of operating a professional studio. Apprenticeships with community partners, where learning outcomes are clearly identified and assessed, can also broaden career possibilities (beyond performance) and provide valuable career training for young musicians.

Flutist Jan Weller has students complete a “lifestyle quiz”38 to help them discover how motivated and resilient they are. The quiz and subsequent discussion questions encourage students to identify how well their stated career goals match with their lifestyle preferences. Students are encouraged to plot (on a simple chart) their strengths and weaknesses as musicians, from some of the criteria outlined earlier in her article. Then, faculty members could identify meaningful musical projects that encourage students to improve areas that will be necessary for future success (as the students have defined it). Some students may even reevaluate some assumptions about career goals based upon what they discover through the activities and discussions with peers and faculty mentors.

Relevance of Class Activities and Assignments

Having students navigate the tricky issue of identity appears to have benefits for future self-fulfillment and career satisfaction.39 There may be an additional benefit, however. If students do not perceive a class topic as having relevance for them, they are less likely to pay attention or consider how it might apply to their future lives. Meaningfulness emerged as an important theme in the analysis of interviews with young musicians who now earn a significant portion of their income from teaching.40 Many of these professional teachers regretted not learning more business and technology skills, for things such as billing and book inventory, while in school. Although these topics, including previewing computer software, cloud-based resources, and sample invoices, were addressed in their pedagogy classes, the material did not seem relevant. Several of the students expected to become performers and did not anticipate teaching large numbers of pupils, thus the material was not retained for future reference. We might encourage students to think about potential relevance not only through identity work but also by creating assignments where they must use current technology and apply pertinent skills. Testimonials from former students and career panels would likely help students to see the potential relevance, as well. In short, assignments that prepare students for the real world must be made more meaningful for the students. They need to believe that work completed now will be important for them when they are functioning as professional musicians. Additionally, if these projects are worth a significant portion of the final grade, students may attend to them more deeply.

Dee Fink made an excellent case for the importance of meaningful learning in his book Creating Significant Learning Experiences. Fink developed a taxonomy of significant learning comprised of six elements: foundational knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn.41 While the first three elements have been addressed by scholars in the past (Bloom’s taxonomy, for example), Fink contends that it is the interplay between the more traditional elements of learning and the integration of the human dimension and caring that make learning more significant or meaningful. Service-learning projects where students engage in musical activities with underprivileged constituents and underserved communities contribute to understanding and empathy beyond oneself and can bring a human dimension to the learning.42 In such settings, undergraduates have the opportunity to experience a more constructivist approach to learning, by applying broad content knowledge in specific settings. Additionally, the inclusion of metacognition (or learning how to learn) in Fink’s taxonomy encourages students to develop skills necessary for lifelong learning and adaptability in fluid careers. This taxonomy could be used to justify the value of interdisciplinary learning experiences for students. Acknowledging the importance of the human dimension along with application of knowledge might explain why service-learning or musical projects with community partners can provide powerful learning experiences for music students. As noted earlier, some conservatories and music schools operate entrepreneurship programs that facilitate such projects for some students.43 However, we might explore ways to foster creativity and skill development through service learning and teaching projects for which all music students would earn credit and develop valuable skills.

Service Learning and Student Organization Opportunities

It is generally acknowledged that service-learning projects can help undergraduates to develop creativity, occupational identity, collaborative skills and empathy toward others and that such projects create lasting change in the undergraduates.44 These projects are meaningful because they require students to apply academic knowledge and reflect upon multiple dimensions of the activity while using their musical skills in service of others.45 On my campus, we have service learning projects that get music education majors into classrooms to read stories to young students in the years preceding their formal teaching internships. We have found, however, that service learning activities where students use their music skills with children from underserved populations are much more meaningful and useful for these undergraduates. For example, we could have students (with much guidance) create short-term curricula and then bring it into classrooms where children do not receive regular music instruction. Pedagogy students could teach beginning instrumental lessons to underserved populations. Undergraduates could work with community schools to create studio web sites and use technology in creative and pedagogical ways to produce online tutorials for students with whom they are working, since fluency with technology and communication techniques are essential skills for musicians.

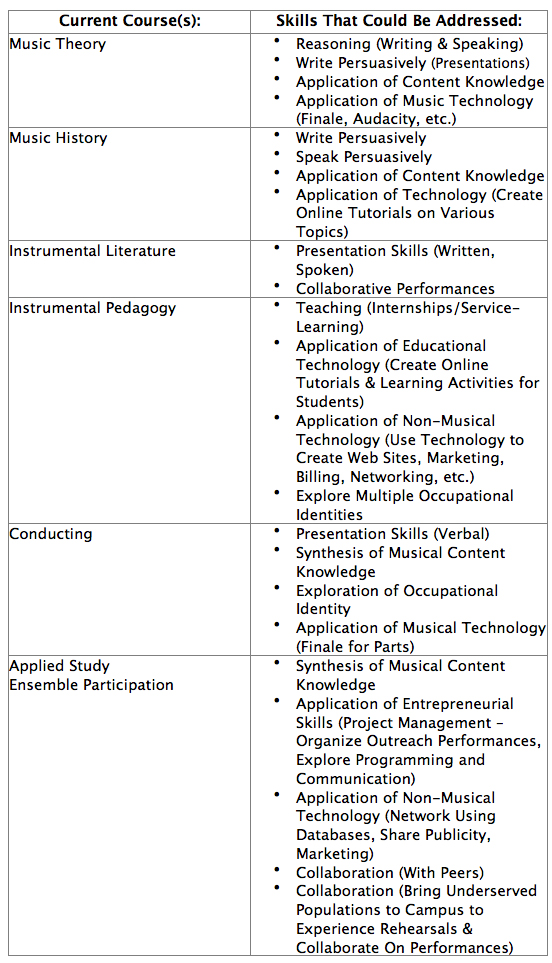

Even though the Millennial students that we teach today are known as digital natives, research suggests that they are not well-equipped to use current educational technology.46 While our students are comfortable using social media to communicate with one another, they may be less at ease with software and technology platforms that will be critical in their professional lives. For example, during undergraduate study they should become adept at using spreadsheets for business activities, creating databases for networking and publicity, developing web sites and online promotional materials that effectively communicate one’s professional “brand,” and employing various musical technologies such as Internet MIDI for teaching, Audacity for audio recording or Finale for music notation, to name just a few examples. Surely, we can create meaningful course components that encourage students to develop skills that they will use in the future, while serving those in need now. See Figure 2 for courses within the current curriculum in which some of these projects could be implemented.

Figure 2. Suggestions of courses where entrepreneurial topics and skills may be included within a typical curriculum.

It is also possible to address some of these skill sets without adding to current course content. Membership and active participation in professional and student music organizations can be an excellent way to encourage students to develop entrepreneurial skills outside of the classroom while serving the community. For example, having students organize performances (in partnership with a local hospital, nursing home or homeless shelter and the music department’s entrepreneurship program, if one exists) can be extremely beneficial. For meaningful personal growth, however, these activities need to be more than just going off-campus and playing; there must be thoughtful preparation and planning, meaningful interaction during the activity and guided reflection afterward. Thus, we might have students organize themselves and take on roles that are new to them (such as stage manager or concert producer); devise a suitable program (in terms of content and length); conduct dress rehearsals; learn how to introduce repertoire; practice speaking to and interacting with audience or community members (both during and following the performance); publicize the event on campus and off campus to learn about marketing (this benefits the organization, the students, and the performance which is the product); and participants learn to communicate and solve problems collectively as they arise. If students complete tasks associated with producing a group performance, they will have learned and employed skills that will be transferred to career projects in the future.

Conclusions

As educators of future professional musicians, we must ensure that, in addition to developing performance expertise, our undergraduate students are acquiring entrepreneurial skills that are necessary for success in the 21st-century professional world. Some of us work in places where true curricular reform that addresses the entrepreneurial aspects of professional musicianship may be plausible. Indeed, several universities have at least one required “entrepreneurship” course, in addition to a cadre of support services that students can use throughout their educational experience.47 Others of us work in institutions where the 19th-century performance-based curriculum is so firmly established that broad reform of the music program is not possible at present. However, individual faculty members who care about the success of their future graduates, should be able to create some effective and meaningful projects that develop entrepreneurial skills within the classes that we teach or within the music organizations that we advise on our campuses.

Projects that encourage undergraduates to explore a full-range of occupational identities should be used so that multiple identities can be developed alongside of the performer identity. Having students engage in service learning activities, that might include teaching or performing and improvising with members of underserved populations in the community can provide powerful application of musical knowledge, awareness of career possibilities, and promote empathy and understanding that transcends social barriers. Creating projects where undergraduates must use current non-musical technology to develop business, networking and other entrepreneurial skills must become part of the curriculum. Likewise, integrating use of current musical technologies for recording, notation and educational assignments provides students with opportunities to develop skills that may be adapted as new technologies emerge. In short, we can encourage students to synthesize material and develop crucial entrepreneurial skills through in-class projects, group workshops, musical activities that encourage new ways to communicate, through off-campus field trips, service-learning projects, or internships and ventures with community partners, to name but a few.

Regardless of how we accomplish this important task, we owe it to our students to help them to develop the interpersonal, entrepreneurial, and communicative skills that they will need to experience success as professional musicians in the 21st century. Throughout undergraduate study we must be cognizant of helping students to explore viable musical identities and to articulate career goals that will be both possible and rewarding for each individual. In short, we must prepare our graduates to succeed in creating and sustaining viable portfolio careers in music. We are each accountable and able to effect some change in the way we prepare our students for the ninth semester, or life as successful professional musicians upon graduation.

Notes

1Bok, Higher Education in America, 29; Selingo, “The Diploma’s Vanishing Value,” Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2013,

2See for example the U.S. White House College Score Card initiative or Benedictus, “Top 10 Things Employers Are Looking For,” The Guardian, April 22, 2013, or Adams, “The 10 Skills Employers Want,”Forbes, October 11, 2013, or, the data source for much of the popular reporting

3NASM, Handbook 2013-14, 101-122.

4Ibid., 87.

5Ibid., 90.

6Ibid., 99.

7Beaching, Beyond Talent, 7; Bennett, Life in the Real World, 13.

8NASM, Handbook 2013-14, 97.

9Ibid., 100.

10Donnelly, “Fostering Creativity,” 156; Haroutounian, Kindling the Spark, 246.

11Beeching, Beyond Talent, 7; Beeching, “Musicians Made in the USA,” 27-28; Bennett, Life in the Real World, 42; Donald, “Performance Students as Future Studio Teachers?, 51; Hannan, “Expanding the Skill Set, ”241; Huhtanen, “How Much Music is Required?,” 70.

12Beeching, Beyond Talent, 6.

13A small survey of graduates from one particular music program with graduates working across the United States revealed that young professionals earned a median income between $15,000-$25,000 during the first five years following graduation (Pike, “Newly Minted Pianists,” 90). A larger survey of musicians of all ages from across the United States, including some who were 40 years post-graduation, (SNAAP 2011 Institutional Data Highlights and Frequency Report); Synthesized information may be found at SNAAP, Snapshot 2014 shows that people with Bachelor of Music degrees currently earn an annual medium income of $45,000.

14Austin et al., “Exploration of Secondary Socialization and Occupational Identity,” 68-9.

15Portfolio, the term more commonly used today, refers to the fact that there is a collection of musical activities (the musician’s portfolio), from which he or she draws to earn income.

16Beeching, Beyond Talent, 9-20.

17SNAAP, 2011 Institutional Highlights, 105.

18Pike, “Newly Minted Pianists,” 88-89.

19Hannan, “Expanding the Skill Set,” 242-244.

20SNAAP, 2011 Institutional Highlights, 84.

21Ibid., 84.

22Maris, “Redefining Success,” 15.

23Bennett and Freer, “Possible Selves,” 17; Perkins, “Rethinking Career,” 89.

24Bennett, Life in the Real World, 14; Weller, “Musician’s Lifestyle,” 179.

25Beeching, Beyond Talent, 11.

26NASM, Handbook 2013-14, 69.

27NetMCDO, Better Assessment, 16.

28NetMCDO homepage and additional information

29CEPROM homepage and additional information

30Ibid.

31National Center for Educational Statistics, 2012 Digest of Education Statistics, 469. PDF of chapter 3 retrieved from this report.

32Burt-Perkins, “Students in Conservatoire,” 56.

33Perkins, “Rethinking Career,” 87.

34Pike, “Newly Minted Pianists,” 90.

35Bennett, Life in the Real World, 186.

36Ibid., 173-175.

37Ibid., 175.

38Weller, “Musician Lifestyle Quiz,” 180-181.

39Bennett, Life in the Real World, 13, 147; Burt-Perkins, “Students in Conservatoire,” 58; Perkins, “Rethinking Career,” 90; Pike, “Newly Minted Pianists,” 89; Weller, “Musician Lifestyle,” 179.

40Pike, “Newly Minted Pianists,” 90.

41Fink, Creating Significant Learning, 30.

42Knapp, “Shelter Concert Series,” 324.

43NetMCDO, Better Assessment, 16.

44Bartolome, “Growing Through Service,” 84; Knapp, “Shelter Concert Series,” 330; Turner, “Music Leadership,” 132.

45Turner, “Music Leadership,” 125.

46Pike, “Educating Musicians to Teach,” 94; Watson and Pecchioni, “Digital Native in College,” 311.

47NetMCDO, Better Assessment, 16.

Bibliography

Adams, Susan. “The Top 10 Skills Employers Want in 20-Something Employees.”Forbes. October 11, 2013.

Association of American Colleges and Universities (AACU). “Top Ten Things Employers Look for in College Graduates.”

Austin, James R., Isbell, Daniel S. & Russell, Joshua A. “A Multi-Institution Exploration of Secondary Socialization and Occupational Identity Among Undergraduate Music Majors.” Psychology of Music 40, no. 1 (2010): 66-83.

Bartolome, Sarah J. “Growing Through Service: Exploring the Impact of a Service-Learning Experience in Preservice Educators.” Journal of Music Teacher Education 23, no. 1 (2013): 79-91.

Beeching, Angela Myles. Beyond Talent: Creating a Successful Career in Music. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2010.

Beeching, Angela Myles. “Musicians Made in the USA: Training, Opportunities and Industry Change.” In Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, edited by Dawn Bennett, 27-43. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC., 2012.

Benedictus, Leo. “Top Ten Things Employers Are Looking For.”The Guardian. April 22, 2013.

Bennett, Dawn. Ed. Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC., 2012.

Bennett, Dawn, Beeching, Angela Myles, Perkins, Rosie, Carruthers, Glen and Weller, Janis. “Music, Musicians and Careers.” In Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, edited by Dawn Bennett, 3-9. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC., 2012.

Bennett, Dawn & Freer, Patrick K. “Possible Selves and the Messy Business of Identifying with Career.” In Educating Professional Musicians in a Global Context: Proceedings of the 19th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), edited by Janis Weller, 14-19. Victoria, Australia: ISME, 2012.

Bok, Derek. Higher Education in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Burt-Perkins, Rosie. “Students in a UK Conservatoire of Music: Working Towards a ‘Diverse Employment Portfolio’?” In Inside, Outside, Downside Up: Conservatoire Training and Musicians’ Work, edited by Dawn Bennett and Michael Hannan, 49-60. Perth: Black Swan Press, 2008.

Donald, Erika. “Performance Students as Future Studio Teachers: Are They Prepared to Teach?” In Educating Professional Musicians in a Global Context: Proceedings of the 19th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), edited by Janis Weller, 49-53. Victoria, Australia: ISME, 2012.

Donnelly, Roisin. “Fostering Creativity Within an Imaginative Curriculum in Higher Education.” The Curriculum Journal 15, no. 2 (2004): 155-166.

Fink, Dee. Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003.

Hannan, Michael. “Expanding the Skill Set.” In Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, edited by Dawn Bennett, 241-245. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC, 2012.

Haroutounian, Joanne. Kindling the Spark: Recognizing and Developing Musical Talent. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Huhtanen, Kaija. “The Education of the Professional Musician: How Much Music is Required?” In Educating Professional Musicians in a Global Context: Proceedings of the 19th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), edited by Janis Weller, 69-73. Victoria, Australia: ISME, 2012.

International Society for Music Education (ISME). “Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician: Vision and Mission.” Retrieved February 7, 2014.

Knapp, David. “The Shelter Concert Series: Reflections on Homelessness and Service Learning.” International Journal of Community Music 6, no. 3 (2013): 321-332.

Maris, Barbara English. “Redefining Success: Perspectives on the Education of Performers.” Symposium 40 (2000): 13-17.

National Association of Schools of Music. NASM Handbook 2013-14. Reston, VA: National Association of Schools of Music, 2013.

National Center for Educational Statistics. 2012 Digest of Education Statistics. PDF of chapter 3 report retrieved November 1, 2014.

Network of Music Career Development Officers (NetMCDO). Better Assessment Through Design Thinking: Network of Music Career Development Officers Nineteenth Annual Conference Proceedings. New York: NetMCDO, 2014.

Perkins, Rosie. “Rethinking ‘Career’ for Music Students: Identity and Vision.” In Life in the Real World: How to Make Music Graduates Employable, edited by Dawn Bennett, 11-26. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC., 2012.

Pike, Pamela D. “Newly Minted Pianists: Realities of Teaching, Performing, Running a Business and Using Technology.” In Relevance and Reform in the Education of Professional Musicians: Proceedings of the 20th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), edited by Glen Carruthers, 85-92. Victoria, Australia: ISME, 2014.

Pike, Pamela D. “Educating Musicians to Teach in the 21st Century: A Case Study of Piano Pedagogy Training that Prepares Musicians to Teach Synchronous Piano Lessons Online.” In Educating Professional Musicians in a Global Context: Proceedings of the 19th International Seminar of the Commission for the Education of the Professional Musician (CEPROM), edited by Janis Weller, 92-96. Victoria, Australia: ISME, 2012.

Selingo, Jeffrey. “The diploma’s vanishing value.” Wall Street Journal, April 26, 2013.

Strategic Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP). “SNAAP 2011 Institutional Data Highlights and Frequency Report.” Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, 2012.

Strategic Arts Alumni Project. “SNAAP Snapshot,” February 2014 .

Turner, Cynthia Johnson. “Music Leadership and Service Learning: Student Engagement in the Context of Outreach, Performance, and Teaching.” Interdisciplinary Humanities 29, no. 3 (2012): 79-91.

Watson, Joseph A., and Pecchioni, Loretta L. “Digital Natives and Digital Media in the College Classroom: Assignment Design and Impacts on Student Learning.” Educational Media International 48, no. 4 (2011): 307-320.

Weller, Janis. (2012). “The musician’s lifestyle quiz” (pp. 179-181). In Bennett, D. (Ed.). Life in the real world: How to make music graduates employable. Champaign, IL: Common Ground Publishing LLC. United States White House College Score Card. Interactive web, retrieved February 7, 2014.